Introduction

The earliest Bronze Age Mediterranean non-human primate (primates hereafter) representations on frescoes are found at the Aegean sites of Knossos (Crete) and Akrotiri (Thera/Santorini) and date to around 1650–1450 bc (for recent reviews, see Binnberg et al., Reference Binnberg, Urbani and Youlatos2021; Urbani & Youlatos, Reference Urbani, Youlatos, Urbani, Youlatos and Antczak2022). Even though they are generally well-known since their early discovery at Knossos (Evans, Reference Evans1921, Reference Evans1935), relatively recent and new descriptions of Theran frescoes depicting primates (Vlachopoulos, Reference Vlachopoulos, Betancourt, Nelson and Williams2007) have been omitted in major studies concerning Minoan primates, as noted by Urbani & Youlatos (Reference Urbani, Youlatos, Urbani, Youlatos and Antczak2022). Moreover, no recent review (e.g. Papageorgiou & Birtacha, Reference Papageorgiou, Birtacha and Doumas2008; Phillips, Reference Phillips2008a, Reference Phillips2008b; Greenlaw, Reference Greenlaw2011; Pareja, Reference Pareja2015, Reference Pareja2017; Urbani & Youlatos, Reference Urbani and Youlatos2020a,Reference Urbani and Youlatosb, Reference Urbani, Youlatos, Urbani, Youlatos and Antczak2022) has reported the existence of any Bronze Age frescoes depicting primates from mainland Greece, where the Mycenaean civilization flourished at that time. This is also the case of other works, such as Cline's (Reference Cline1991, Reference Cline, Davies and Schofield1995) study on the presence of Egyptian primatomorphic objects on Mycenaean sites, Wolfson's (Reference Wolfson2018) iconographical analysis on ‘monkeys and simianesque creatures’ from ancient Greece, and Urbani's (Reference Urbani, Youlatos and Binnberg2021) recent comprehensive assessment on global archaeoprimatological patterns. Thus, there is a widespread assumption that monkeys were not depicted in Mycenaean frescoes, and, consequently, that the significance of this animal in Mycenaean culture was negligible (Lang, Reference Lang1969: 104; Immerwahr, Reference Immerwahr1990: 108, 162, 165; Kontorli-Papadopoulou, Reference Kontorli-Papadopoulou1996: 123; Crowley, Reference Crowley, Laffineur and Palaima2021: 202).

However, an article by Maria Kostoula and Joseph Maran (Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012: 210–12) contains a discussion of a fresco fragment from the Mycenaean site of Tiryns which, according to them, shows a monkey. Since this finding was overlooked by all other analyses of primates in Aegean Bronze Age iconography, it is appropriate to discuss this fragment at greater length and highlight its archaeoprimatological and art historical significance. In the present article, this fresco will be re-described in detail, examined from a primatological perspective, and assessed within its art historical context.

Primate Imagery in Mycenaean Greece

The relationship of the inhabitants of the Mycenaean Greek mainland with primates remains tenuous, particularly when compared with the relatively ample primate imagery of the Minoans (Papageorgiou & Birtacha, Reference Papageorgiou, Birtacha and Doumas2008; Phillips, Reference Phillips2008a, Reference Phillips2008b; Greenlaw, Reference Greenlaw2011; Pareja, Reference Pareja2015, Reference Pareja2017; Urbani & Youlatos, Reference Urbani and Youlatos2020a,Reference Urbani and Youlatosb, Reference Urbani, Youlatos, Urbani, Youlatos and Antczak2022; Binnberg et al., Reference Binnberg, Urbani and Youlatos2021). The only other objects depicting monkeys found on Mycenaean lands are either imports from Egypt or directly influenced by Cypriot or Near Eastern artistic traditions. Among these, the urban complexes of Tiryns and Mycenae have yielded a couple of imported primatomorphic figurines that can be associated with New Kingdom Egypt (McDermott, Reference McDermott1938; Cline, Reference Cline1991, Reference Cline, Davies and Schofield1995). A bluish cartouche figurine found in Mycenae in 1896 (National Archaeological Museum of Athens, inventory number EAM 4573), bearing the name of Amenhotep II (reigned 1427–1401 bc), shows a creature (Cline, Reference Cline1991: pl. 1) whose prominent lateral whiskers, high forehead, rounded head, and laterally placed nostrils suggest a papionin (Papio spp.). Kilian (Reference Kilian1979: 405, fig. 30; Tiryns inv. LXI 36/88 a12.46) and Cline (Reference Cline1991: 34, pl. 2) describe another Egyptian primate frit figurine painted in blue with a similar name, found in Tiryns in 1977. In this object, possibly a baboon-like monkey infant is clinging to the body of its mother, but the piece is so poorly preserved that vital details that could contribute to a definitive identification are missing. From Mycenae, Sakellarakis (Reference Sakellarakis1976: 178, pl. IV, 9) reported a fragment of an alabaster vase depicting the side of a body, a small hand holding the body, and the left leg of a monkey-like animal (National Archaeological Museum of Athens, inventory number EAM 2657), most likely representing an infant clinging to its mother. Sakellarakis (Reference Sakellarakis1976: 178) also refers to another alabaster piece from Tiryns representing the right side of a face showing the ear, muzzle, and formerly inlaid eye of a possible primate (National Archaeological Museum of Athens, inventory number EAM 6250; according to Cline (Reference Cline1991: 38), the find location was mislabelled, and it is from Mycenae).

Tiryns also yielded another primate- or demon-like Mycenaean rhyton dating from the fourteenth to thirteenth century bc. Maran (Reference Maran, Schallin and Tournavitou2015: 282) commented that the object was ‘furnished with inlaid eyes and shaped like a head of a monkey or the Near Eastern demon Humbaba’ (the guardian of the Forest of Cedars, the place where the gods inhabited; a representation not found before in the Aegean, as indicated by Kostoula & Maran, Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012). Unfortunately, its fragmentary nature impedes an unambiguous restoration of the object (Kostoula & Maran, Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012: fig. 10). The authors suggested that this primate-like image might have served a local Mycenaean religious purpose; that may indicate a cultural borrowing from the Near East and Egypt, where primates and humans display proven interconnections (see, e.g., Vandier d' Abbadie, Reference Vandier d'Abbadie1964, Reference Vandier d'Abbadie1965, Reference Vandier d'Abbadie1966; Hamoto, Reference Hamoto1995). Moreover, as the object was found in a context related to Cypriot or even Levantine artisans, it might have been influenced by Cypriot or Near Eastern imagery (Kostoula & Maran, Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012: 218). From a morphological perspective, the object featuring forward set eyes, implied high forehead, pointed nose with slightly laterally set nostrils, and prominent lateral ears cannot be unequivocally identified as a monkey, a demon, or even a grotesque human-like wrinkled face.

Finally, a small (17.5 mm long, 17.5 mm wide) stone lentoid seal depicting a human facing a monkey is kept in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens (CMS I 377). Although the seal is probably of Minoan origin, the impression was most likely made at Pylos in the south-eastern Peloponnese, in the Late Helladic IIIB–C period (Tamvaki, Reference Tamvaki, Darcque and Poursat1985; Krzyszkowska, Reference Krzyszkowska2005; Philips, Reference Phillips2008a: n. 952; Pareja, Reference Pareja2015: fig. 5.10; Crowley, Reference Crowley, Laffineur and Palaima2021: fig. XLI.12). In a recent review, Urbani and Youlatos (Reference Urbani, Youlatos, Urbani, Youlatos and Antczak2022: fig. 10.11m), tentatively identified the monkey as a baboon, based on its long snout, waisted body, and relatively short tail with a tuft at the end.

This brief overview indicates that there are no unambiguous three-dimensional representations of primates of Mycenaean origin. However, as the next sections show, this may not be the case for a two-dimensional depiction.

Mycenaean Tiryns

The Mycenaean civilization flourished in the central and southern parts of mainland Greece during the last phase of the Bronze Age (1750–1050 bc), with major centres such as Mycenae, Tiryns, Pylos, Orchomenos, Thebes, and probably Athens (Schallin & Tournavitou, Reference Schallin and Tournavitou2015). Tiryns, located in the north-eastern Peloponnese (Figure 1), was one of the main harbours of the Argolid, with strong archaeological indications of its participation in long-distance exchange (Maran, Reference Maran and Cline2010, Reference Maran, Schallin and Tournavitou2015). The site included several settlement areas in the lowlands around the fortified citadel, of which the Upper Citadel is one of the most impressive and best-preserved Mycenaean palaces of the Late Helladic period (LH IIIA–B, fourteenth to thirteenth centuries bc) (Maran, Reference Maran and Cline2010).

Figure 1. Location of Tiryns within the Eastern Mediterranean. Map data: Google Earth, Landsat/Copernicus Data SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO Geobasis-DE/BKG, ©2009 Inst. Geogr. Nacional Mapa GISrael.

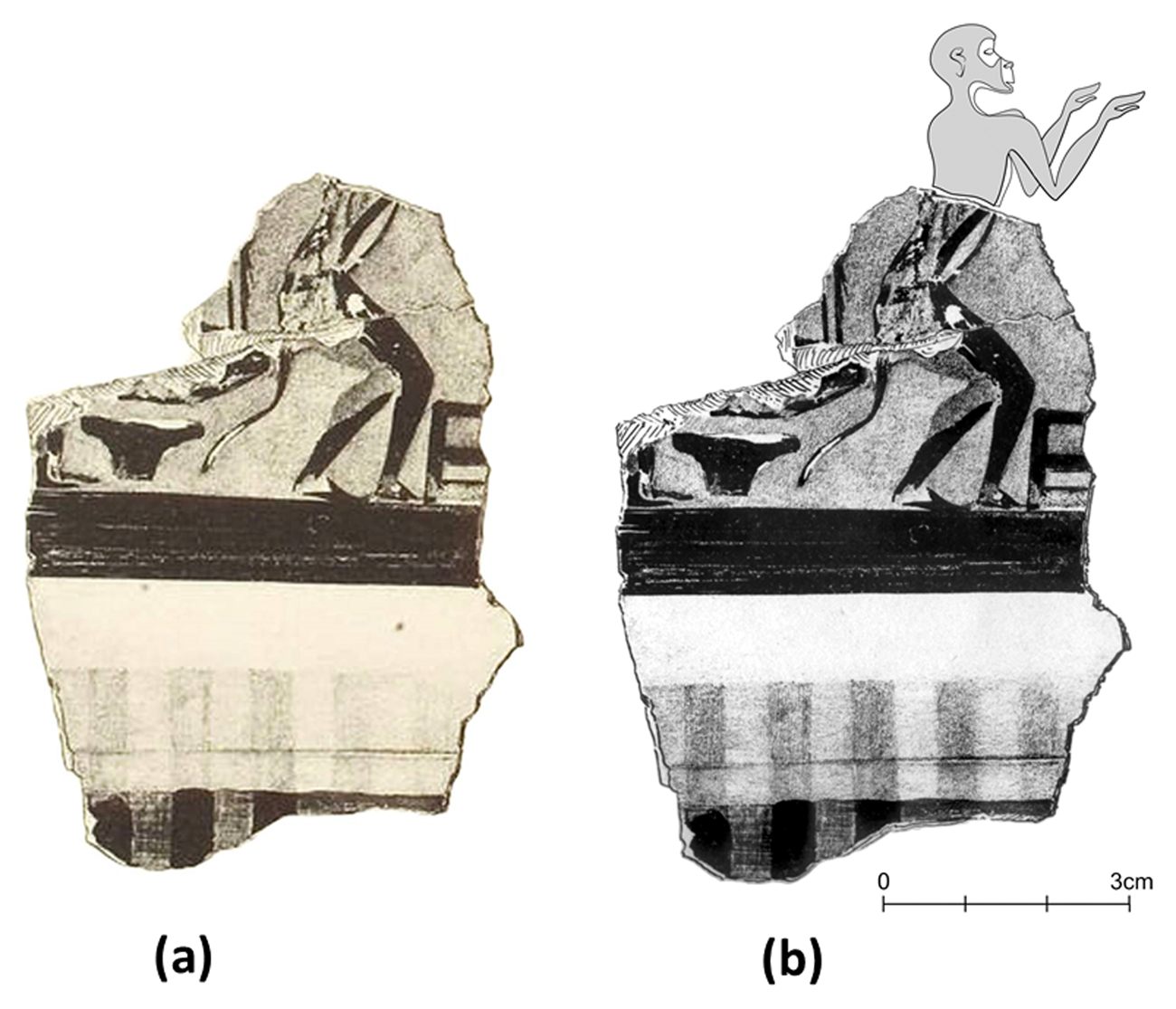

Since the early campaigns of Heinrich Schliemann in 1884–1885 (Schliemann, Reference Schliemann1886), the site has been excavated by collaborative teams of German and Greek archaeologists until today (Maran, Reference Maran and Cline2010; Maran, pers. comm.). Among the pioneers was the German archaeologist Gerhart Rodenwaldt (1886–1945), who published an extensive study of the frescoes found at Tiryns (Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912). In this monograph, a drawing of a small fragment of a fresco printed in sepia (Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912: pl. II.7) shows a biped, of which only the lower half of the body, the two legs, and the tail are visible (Figure 2a). This figure subsequently became the subject of different interpretations. Rodenwaldt (Reference Rodenwaldt1912: 17) interpreted it as a human/animal hybrid, while other authors identified a human wearing an animal hide (Vermeule, Reference Vermeule1974: 50; Kilian, Reference Kilian, Hägg and Marinatos1981: 50; Lurz, Reference Lurz1994: 128–29; Weilhartner, Reference Weilhartner, Alram-Stern and Nightingale2007: 346; Kostoula & Maran, Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012: 211). Kostoula & Maran (Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012) were the first to propose that this figure may represent a monkey and suggested a reconstruction, reproduced here in Figure 2b.

Figure 2. The tailed partial body on the miniature fresco fragment from the Upper Citadel of Tiryns. a) in sepia from Rodenwaldt (Reference Rodenwaldt1912: pl. II.7; b) proposed reconstruction after Kostoula and Maran (Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012: fig. 10b based on Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912: pl. II:7). Image a) Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Public Domain; image b) reproduced by permission of J. Maran.

Description

The fresco fragment

Between 1909 and 1910, Rodenwaldt took part in the excavations of the Upper Citadel at Tiryns and two years later he published the fresco fragments found in these campaigns (Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912). Among these, he described a small fresco fragment recovered from the debris of the palace, found at a shallow depth north-east of the Byzantine church. The dimensions of the fragment, currently in the National Museum at Athens (inventory number 5879ι), were recorded as 87 mm high, 62 mm wide, and around 28 mm deep (Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912: 16). The fragment (Figure 2a) was described thus: ‘The piece is completely burnt; the originally blue background has changed to grey, the yellow stripe of the dentate band to blotchy red. The upper stripe of the dentate band was probably grey from the start, since its colouration is different from that of the background of the picture. Its ornamentation now has a negative effect, since the intervals corresponding to the red horizontal lines of the lower stripe appear darker because the black that has broken off from the horizontal lines has taken away the grey below. The red in the image has also partially broken off and its presence can only be recognized by the different colours of the ground. White has been preserved on the back and tail of the figure and on the right edge of the object on the left. In the lower part of the grey dentate band, we see a line pressed in with a string, the preliminary drawing for the dividing line between the two dentate bands, which was not adhered to during execution. The whole fragment was covered with a solid sinter that was difficult to remove’ (Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912: 16, pl. II.7; translation by the authors). Although the find's context makes its chronological position uncertain, Kostoula & Maran (Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012: 211) confidently placed it between the Early and Late Palatial Period (Late Helladic IIIA or IIIB; around 1420–1200 bc).

We re-examined the fragment (Figure 3) fully at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, re-described it and photographed it for the first time since its discovery more than a century earlier. The fragment was burnt and is in a relatively poor condition: it is broken in its upper part and has been glued. Its actual measurements, via digital calliper (Mitutoyo™, Japan), are 85 mm high, 65 mm wide, and 25 mm deep. Most painted features are in relief, indicating a heavy layer of painting. This thick layer of paint is either destroyed (e.g. on most of the biped) or simply flaked (e.g. right leg of the figure, where the relief persists). Only a few parts indicate light painting (e.g. on the figure's belly). When originally curated, the painted side of the fragment was conserved with varnish, adding a glossy surface to the piece. A complete documentation of this miniature fresco, including a detailed chromatic record by Munsell Colour Chart™ and a photograph of the back side of the fragment, can be found in the online Supplementary Material (Table S1 and Figures S1 and S2).

Figure 3. The tailed partial body of a miniature fresco from Tiryns, in colour. The bar equals 1 cm. Photograph by D. Youlatos with permission from the Εθνικό Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο, Συλλογή Προϊστορικών, Αιγυπτιακών, Κυπριακών και Ανατολικών Αρχαιοτήτων, ©Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού και Αθλητισμού/ΟΔΑΠ (National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Department of Collection of Prehistoric, Egyptian, Cypriot and Near Eastern Antiquities), ©Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/ HCRMDO.

The scene

On the fragment, a bipedal figure (partial lower body, two flexed legs, and a hanging tail) is depicted leaning forward in front of a rectangular object to the right. To the left, behind the feet of the figure stands a vessel with a tapering base and flaring rim. Above, there is another, larger object with a curved base. This ‘floating’ object may represent an undetermined structure that most probably lies in the background of the scene. Further to the left, behind the vessel on the ground are two feet belonging to another figure. The way the feet are set close to each other in contact with the ground suggests a fully standing biped, most likely to be a human. The elements of the scene are rendered mostly in dusky red set over a greenish grey background (see below).

The tailed partial body

Occupying the upper right quarter of the small fragment, the whole figure, whose head and arms are missing, measures just 40 mm in height and the body is 10 mm wide. Each thigh is 20 mm long and so is the length of each shin. The colour of the body lines, the thighs, shins, and the tail are dusky red. The damaged parts and the faded parts are greenish to bluish grey. This is also the colour of the belly, which is strongly differentiated from the dark-coloured body. The figure is leaning forward, a posture that, although possibly related to the figure's action, is probably implying a bipedally-standing animal and not a human, who would stand more upright, as in most Mycenaean wall-paintings (see anthropomorphic images in Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912; Lang, Reference Lang1969; Brecoulaki et al., Reference Brecoulaki, Davis and Stocker2015; Tournavitou, Reference Tournavitou2017).

The back of the tailed body is straight, whereas the belly (bearing the colour of the background) is lightly convex. The relatively narrow waist is evident. The right leg is on the foreground and flexed; it is proximally grey, with only its dorsal part dusky red (thigh). Distally, the shin is also dusky red. The right foot is damaged and only the outline survives; it is set in full contact with the ground. The left leg is in the background but stands in front of the right leg; it is less flexed, and the dusky red colour persists throughout, until the level of the foot. The left foot seems to establish a firm contact with the ground and supports the body weight.

The tail is smoothly curved, appears flexible, dynamic, and is shown in relief. It is narrow, relatively long, but shorter than the body or the legs (the tail-leg ratio is around 0.74). The distal part appears slightly wider than the proximal part. The tail appears to develop organically from the back, and it is not in an elevated position. However, this part is partially destroyed and broken. The distal end appears to show a small difference in colouration where a whitish longitudinal stroke appears. This part is covered by soil remnants and difficult to discern but the two colours are still visible.

The Tailed Partial Body of Tiryns: Identification

As noted by Kostoula & Maran (Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012), when Rodenwaldt wrote his monograph, the primatomorphic frescoes at Knossos were yet unknown; thus he identified the figure as a hybrid involved in some kind of cult activity (Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912: 17). By contrast, Vermeule (Reference Vermeule1974: 50) and later Kilian (Reference Kilian, Hägg and Marinatos1981: 50) interpreted the Tiryns figure as a man wearing an animal hide featuring a long-curved tail. As Lurz (Reference Lurz1994: 128–29) observed, hybrid mythical beings merging human feet with an animal body are generally unknown in Mycenaean iconography, which is why he suggested that the figure was a priest wearing an animal hide who, judging from his posture, is probably depicted dancing. This opinion was shared by Weilhartner (Reference Weilhartner, Alram-Stern and Nightingale2007: 346), who claimed that the figure is a human wrapped in an animal skin with a long tail, most probably associated with a ritual practice. After observing the image published by Rodenwaldt (Reference Rodenwaldt1912: 16, pl. II.7) (here Figure 2a), Kostoula and Maran (Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012: 211) were the first scholars to suggest that the image of this wall-painting is likely to represent a monkey, based on close morphological and compositional similarities with the primatomorphic fresco from Room 3a, Xeste 3 at Akrotiri on Thera (Doumas, Reference Doumas1992: 158–59) (Figure 4). They also pointed out that this interpretation had surprisingly never been proposed before, probably because of ‘the fact that the colour of the figure does not seem to conform to the convention to depict monkeys as blue’ (Kostoula & Maran, Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012: 211).

Figure 4. Minoan scene of ´The Offering to the Seated Goddess´ from Room 3a, Xeste 3, Akrotiri, Thera. Photograph ©Klearchos Kapoutsis, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY.

From a primatological perspective, the Tiryns figure shows a set of physical features, such as robust thighs and body, a clearly delineated and differently coloured belly, moderately narrow waist, and a tail base located on the upper part of the rump, that appear to suggest the representation of a monkey. Moreover, the tail seems to be part of the animal, a continuation of the rump and not part of a costume, or furry garment, or attachment, which further highlights the animal nature of the bipedal figure. When compared to the descriptors suggested for Minoan papionins such as the ‘narrow waist, dorsal position of the tail base (and) elevated limb configuration’ (Urbani & Youlatos, Reference Urbani and Youlatos2020a: 3), the Tiryns image shows the general form of a baboon-like primate.

Regarding the figure's unusual colour, Rodenwaldt's published drawing is in sepia (Figure 2a) and his description (Reference Rodenwaldt1912: 16, pl. II.7; see translation above) does not allow a proper chromatic characterization of the body – he only mentioned the presence of white on the figure. Yet, although Kostoula and Maran (Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012) did not mention the reddish colour, they highlighted the unconventional colouration of the monkey, which might explain why no one had proposed the interpretation of a primate representation before, and suggested that this deviation could indicate a change in colour conventions in the long process of artistic transfer from the Aegean islands to the Greek mainland. Based on our own macroscopic examination of the fragment, we can confirm that the figure was mostly painted in dusky red and pink tones with some greenish/greyish veins on the belly, torso, and upper legs (see also Supplementary Table S1) which probably resulted from the damage and flaking of the surface, revealing the bluish/greenish underpainting.

While a change in artistic conventions is certainly possible, other factors may also have played a role. The fresco fragment from Tiryns is not only the first identified Mycenaean wall-painting of a monkey, but it is also the first miniature fresco with this subject in the region. It is very likely that the artist may have chosen a largely monochrome colour scheme to make the figures stand out from the background. On the other hand, the artist may have been inspired by the use of monochrome red, as in Mycenaean pictorial vase-painting such as the red zoomorphic, anthropomorphic, and geometric motifs of Mycenaean pottery (Figure 5a–f) (Vermeule & Karageorghis, Reference Vermeule and Karageorghis1982; Pliatsika, Reference Pliatsika and Vlachopoulos2018).

Figure 5. Monochrome scenes in reddish tones on Mycenaean pottery from Eastern Mediterranean archaeological sites: a) unknown location; b) Enkomi, Cyprus; c) Tiryns; d) Mycenae; e) Evangelistria, mainland Greece; f) Palea Epidavros, mainland Greece. Photographs a–e) ©Zde, Wikimedia, CC BY; photograph f) ©Schuppi, Wikimedia, CC BY.

In addition to rendering physical traits of primates in a relatively naturalistic way (cf. Cameron, Reference Cameron1968; Masseti, Reference Masseti1980; Doumas, Reference Doumas1992; Groves, Reference Groves2008; Urbani & Youlatos, Reference Urbani, Youlatos, Legakis, Georgiadis and Pafilis2012, Reference Urbani and Youlatos2020a,Reference Urbani and Youlatosb, Reference Urbani, Youlatos, Urbani, Youlatos and Antczak2022; Binnberg et al., Reference Binnberg, Urbani and Youlatos2021), Minoan images of papionins also include aspects that highlight their perceived similarities to humans (see Greenlaw, Reference Greenlaw2011; Chapin & Pareja, Reference Chapin, Pareja, Laffineur and Palaima2021) and ‘were attributed more anthropomorphic behaviours and depicted in sacred or ritual events’ (Urbani & Youlatos, Reference Urbani and Youlatos2020a: 3). The colour red is universally associated with energy and vitality, and in Aegean wall-paintings is frequently represented as the skin colour of adult males (Morgan, Reference Morgan, Davis and Laffineur2020). Perhaps, the red fur of the Tiryns figure may have been considered appropriate for an animal that displays noticeable human traits.

In this context, it must be emphasized that the feet of the Tiryns figure (Figure 6a–b) strongly resemble human feet as they are rendered in other Mycenaean frescoes (see Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912: 17, pls. II8, VIII, XIV12) (see Figure 6c–d). In the Minoan primate frescoes, anthropomorphic pedal traits in baboons were rendered either with flexed digits (Figure 6e) or as triangular, proportionally short, and pointy extremities, slightly resembling human feet (Figure 6f). It is likely that these traits were originally supposed to further highlight the intermediate nature of these animals. In the Tiryns fresco, the feet of the animal are human-like, a fact that prompted some scholars to see a human-animal hybrid or a human dressed in a fur. Later, the use of human feet will re-appear in primatomorphic motifs in Classical Greece (e.g. Figure 6g: Attic amphora, fifth century bc; see Tompkins, Reference Tompkins1994: 24). Thus, as suggested by Kostoula and Maran (Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012) and in our study, the current evidence suggests that the most plausible identification of the figure on this miniature fresco from Tiryns is that it is a primate.

Figure 6. Mycenaean primate and human feet compared to Minoan and Greek primate feet: a) detail of the feet of the tailed Tiryns partial body (from Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912: pl. II.7); b) photograph of the same; c) Mycenaean human feet (from Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912: pl. II.8); d) Mycenaean woman's feet (from Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912: pl. VIII). Minoan depictions of papionin feet: e) detail of the foot of the baboon from Room 3a, Xeste 3, Akrotiri, Thera (see Figures 4 and 8e); f) detail of the foot of the baboon from the Early Keep, Knossos, Crete (see Figure 8d). Greek depictions of primate feet: g) amphora of Attic origin found at Capua, (Italy), 470–450 bc, with details of the primate feet in the expanded circles (British Museum, inventory number 1873.8-20.364). Images a) and c–d) Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Public Domain; photograph b) by D. Youlatos; photograph e) ©Klearchos Kapoutsis, Wikimedia, CC BY; photograph f) ©ArchaiOptix, Wikimedia, CC BY; photograph g) ©Vassil, Wikimedia, CC BY.

The Tailed Partial Body of Tiryns: Interpretation

Several similarities can be found among the comparanda in the record of Aegean Bronze Age primatomorphic frescoes. For example, the depiction of a lighter belly in the figure from Tiryns is comparable to the white bellies of other Aegean monkeys (Figure 7) and this colour contrast between the dorsal and ventral areas to represent the primate body was most likely an artistic convention in frescoes depicting primates in both the insular and mainland Greece Bronze Age cultures. Moreover, there are similarities with other scenes involving baboons (Urbani & Youlatos, Reference Urbani and Youlatos2020a,Reference Urbani and Youlatosb, Reference Urbani, Youlatos, Urbani, Youlatos and Antczak2022). The depictions of the thigh, buttocks, and tail base are virtually identical in the Tiryns fragment (Figure 8a–b) and in the baboon from the Minoan House of the Frescoes at Knossos (Figure 8c). Finally, the lower torso of the tailed body from Tiryns is very similar in shape, position, and colour contrast to the papionin from Room 3a of Xeste 3 at Akrotiri on Thera (Figure 8e). As already observed by Kostoula and Maran (Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012: 211), this latter scene (see Figure 4) displays further parallels regarding the composition and can provide clues as to the original context of the incomplete image from Tiryns (see Doumas, Reference Doumas1992: 158–59). In the Akrotiri fresco, a young woman is pouring crocus flowers from a basket into a large pannier on the ground. To the right, a baboon is standing in front of a tripartite podium. Its foot is placed on the lower level of the platform right next to a smaller pannier with saffron from which the monkey has taken a bunch to offer it to a large woman (a goddess?) who is seated on the highest level of the podium. On the fragment from Tiryns, the rectangular striped object on the right may have formed part of a similar architectural structure (Kostoula & Maran, Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012: 211; cf. Militello, Reference Militello and Blakolmer2020: figs. 17-20). Moreover, the monkey standing in front of the platform is shown in a pose very similar to that of the baboon from Akrotiri. Although the Tiryns torso is preserved almost to the armpits, the arms are not visible which could mean that they were likewise raised in an offering gesture. Based on these similarities, one could even go further and suggest that the vessel standing on the ground is a basket, comparable to the containers for gathering crocus flowers used by the women in the Theran frescoes (cf. Tzachili, Reference Tzachili and Morgan2005). Following this line of thought, the large ‘floating’ object with a curved base may be the equivalent to the large pannier into which the basket was emptied.

Figure 7. The lighter belly shown on Bronze Age Aegean primatomophic frescoes (red arrows): a) detail of the belly of the Tiryns tailed partial body (from Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912: pl. II.7; b) photograph of the same. Minoan primatomorphic wall-painting images: c) Early Keep, Knossos, Crete (left: photograph, right: photograph after reconstruction by Émile Gilliéron (1850–1924)); d) Sector Alpha, Akrotiri, Thera; e) Room 3a, Xeste 3, Akrotiri, Thera (see Figures 4 and 8e); f), Room 6, Complex Beta, Akrotiri, Thera. Image a) Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Public Domain; photograph b) by D. Youlatos; photograph c) (left) ©ArchaiOptix, Wikimedia, CC BY; (right) ©Zde, Wikimedia, CC BY; photograph d) (left) by B. Urbani; (right) by M. Hamaoui with permission from Andreas Vlachopoulos, Akrotiri Excavations, Thera; photograph e) ©Klearchos Kapoutsis, Wikimedia, CC BY; photograph f) by B. Urbani.

Figure 8. The tailed partial body from Tiryns and lower parts of the bodies of Minoan papionins from original fresco fragments: a) the Tiryns tailed partial body (from Rodenwaldt, Reference Rodenwaldt1912: pl. II.7); b) photograph of the same. Minoan primatomorphic wall-painting images: c) House of Frescoes, Knossos; d) Early Keep, Knossos, Crete; e) Room 3a, Xeste 3, Akrotiri, Thera. Image a) Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Public Domain; photograph b) by D. Youlatos; photograph c) ©Zde, Wikimedia, CC BY; photograph d) ©ArchaiOptix, Wikimedia, CC BY; photograph e) ©Klearchos Kapoutsis, Wikimedia, CC BY.

If we assume that the miniature fresco from Tiryns is part of a scene similar to that shown at Akrotiri (Figure 4), this would add one more image to a small corpus of Aegean depictions connecting monkeys with important female figures or deities. This link is not only found in the Akrotiri fresco, but also, for example, on a ring from Kalyvia (CMS II,3 103), where a monkey accompanied by a woman is approaching a large sitting female figure. Moreover, the scene from Tiryns would possibly corroborate the special connection between monkeys and saffron (see Day, Reference Day2011). Monkeys picking crocus flowers in baskets are shown in the fresco from the Early Keep at Knossos (Figure 7e), the oldest known fresco depicting a primate from the Aegean. A monkey holding a basket for a woman gathering (crocus) flowers is also shown on a seal from Sitia (CMS III 358). It remains unknown what the specific significance of this link was, but the fragment from Tiryns may suggest that this association continued into the Mycenaean palatial period.

The Tiryns fresco fragment contradicts the widespread assumption that monkeys were not represented in local Mycenaean iconography (Lang, Reference Lang1969; Immerwahr, Reference Immerwahr1990; Kontorli-Papadopoulou, Reference Kontorli-Papadopoulou1996; Crowley, Reference Crowley, Laffineur and Palaima2021). The Tiryns fragment clearly ties into an Aegean tradition of primatomorphic depictions and the scene is likely to have been executed by a Mycenaean artist. It also adds to recent research on Mycenaean fresco iconography, which found that there is a wider variety of animals depicted than previously known. While emblematic images of lions and bulls, or hunting scenes featuring dogs, boars, and deer, have long been identified as power symbols of the palatial elite, the function of newly-discovered depictions of waterbirds (Aravantinos & Fappas, Reference Aravantinos, Fappas, Brecoulaki, Davis and Stocker2015: figs. 5, 10; Tournavitou & Brecoulaki, Reference Tournavitou, Brecoulaki, Brecoulaki, Davis and Stocker2015: figs. 7, 10), wild goats (Tournavitou & Brecoulaki, Reference Tournavitou, Brecoulaki, Brecoulaki, Davis and Stocker2015: fig. 6), snakes (Tournavitou & Brecoulaki, Reference Tournavitou, Brecoulaki, Brecoulaki, Davis and Stocker2015: fig. 10), scorpions (Tournavitou & Brecoulaki, Reference Tournavitou, Brecoulaki, Brecoulaki, Davis and Stocker2015: fig. 9), and marine animals (Boulotis, Reference Boulotis, Brecoulaki, Davis and Stocker2015; Egan & Brecoulaki, Reference Egan, Brecoulaki, Brecoulaki, Davis and Stocker2015; Tournavitou & Brecoulaki, Reference Tournavitou, Brecoulaki, Brecoulaki, Davis and Stocker2015: figs. 14–16) is often difficult to determine. This is due to the images’ fragmentary condition and the fact that most of these animals are not mentioned in the Linear B sources (Duhoux, Reference Duhoux, Laffineur and Palaima2021). These written documents mainly deal with animal practices that are of administrative importance such as cattle herding and sheep rearing (Halstead, Reference Halstead, Bennet and Driessen1998–99), whereas the ideological or religious significance of animals is only alluded to. Thus, animals appear in lists that were drawn up in preparation for feasts, and the archaeozoological data also suggest that bulls and pigs were sacrificed (Hamilakis & Konsolaki, Reference Hamilakis and Konsolaki2004; Stocker & Davis, Reference Stocker, Davis and Wright2004). Monkeys are neither mentioned in Linear B sources nor have their bones ever been found at a Mycenaean site, which makes the fresco fragment from Tiryns all the more relevant for reconstructing Mycenaean human-animal relationships.

As in the case of most Minoan monkeys, the baboon, a primate species of North African range, could have been used as the living model. As mentioned, the Tiryns miniature fresco is dated to between 1420 and 1200 bc (Kostoula & Maran, Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012: 211). Between the fifteenth to thirteenth centuries bc, material culture, iconography, and written sources confirm the existence of multiple diplomatic contacts between the Mycenaean sphere and Egypt (Merrillees, Reference Merrillees1972; Cline, Reference Cline, Galaty and Parkinson2007; Kelder, Reference Kelder2009, Reference Kelder2013). At this time, Tiryns was the main Mycenaean harbour in the Peloponnese and a place of intense commercial and cultural exchange (Cline, Reference Cline, Galaty and Parkinson2007; Maran, Reference Maran and Cline2010, Reference Maran, Schallin and Tournavitou2015), a position that is further supported by the discovery of the Egyptian objects depicting baboons mentioned above. These artefacts were imported from workshops under the rule of Amenhotep II (Cline, Reference Cline1991). During the same period in New Kingdom Egypt, baboons were commonly represented in art (Pio, Reference Pio2018; Dominy et al., Reference Dominy, Ikram, Moritz, Wheatley, Christensen and Chipman2020; Urbani & Youlatos, Reference Urbani, Youlatos, Urbani, Youlatos and Antczak2022): for instance, the tomb of Rekhmire (TT100), who was the vizier to Amenhotep II, includes a fresco that depicts baboons along with Puntians, Nubians, and other Bronze Age Aegean peoples paying tribute (see discussion in Binnberg et al., Reference Binnberg, Urbani and Youlatos2021; Urbani et al., Reference Urbani, Youlatos and Binnberg2021; Urbani & Youlatos, Reference Urbani, Youlatos, Urbani, Youlatos and Antczak2022). Moreover, a recent study confirmed the presence of Hamadryas baboon (Papio hamadryas) mummies in Egyptian tombs (KV50, KV51, and KV52) related to the reign of Amenhotep II (Dominy et al., Reference Dominy, Ikram, Moritz, Wheatley, Christensen and Chipman2020). These cultural contacts between the Greek mainland and Egypt seem to further support the identification of a baboon in the miniature fresco from Tiryns. Baboons were predominantly connected with ritual contexts in Egypt and the Near East (e.g. Hamoto, Reference Hamoto1995; Pio, Reference Pio2018; Urbani & Youlatos, Reference Urbani, Youlatos, Urbani, Youlatos and Antczak2022) and the Egyptian association was taken over by the Minoans and apparently continued by the Mycenaeans.

A Tailed Partial Body, A (Still) Partial Conclusion

The phenotypic, cultural, historical, and comparative evidence concerning the tailed partial body depicted on a small fragment from a miniature fresco recovered in Late Helladic Mycenaean Tiryns seems to point to the depicted animal being a monkey, as originally proposed by Kostoula & Maran (Reference Kostoula, Maran, Lehmann, Talshir, Gruber and Ahituv2012). After close examination, we propose that it is not only a monkey but most probably a baboon-like primate. In addition, we note that this is the first known fresco representing a primate in mainland Europe, executed almost a millennium before the Etruscan primatomorphic wall-paintings of the fifth to fourth centuries bc in the Italian peninsula (see Urbani, Reference Urbani2021). Unlike other objects depicting monkeys found at Mycenaean sites, it is the only representation that is clearly dependent on the local Aegean artistic tradition. It shows a baboon similar to those in Minoan frescoes, which is actively involved in a cult scene that might once have included a female figure on a platform and vessels, as also depicted in Minoan frescoes. The uniqueness of the representation within Mycenaean iconography and its fragmentary condition, however, still limits our understanding of the relationship this society had with this mammalian group. We hope that further discoveries will shed more light on this issue; fortunately we benefit from ongoing and continuous research on Mycenaean frescoes.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to Konstantinos Nikoletzos, Aikaterini Kostanti, and Vassiliki Pliatsika from the Department of Collections of Prehistoric, Egyptian, Cypriot, and Eastern Antiquities of the National Archaeological Museum of Athens for granting permission to study the material and support and help during our visit. We are most grateful to Joseph Maran (Heidelberg University), for promptly and enthusiastically replying to our inquiries and for his comments on an earlier draft of this article, to Andreas Vlachopoulos (University of Ioannina/Akrotiri Excavations), for sharing Figure 7d-right, to Segundo Jiménez (Venezuelan Institute for Scientific Research), for assisting in the preparation of figures, and to Dimitris Kostopoulos (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki), for the loan of his Munsell Colour Chart™. For providing access of their collections, many thanks go to the librarians of the Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg. This research benefitted from the support of the library of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaing, the Historical-Archaeological Library of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, and the Archaeological Library at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg. Dionisios Youlatos is supported by the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and Bernardo Urbani by the Venezuelan Institute of Scientific Research, the Leibniz Institute for Primate Research/German Primate Centre and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Finally, we are indebted to the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2023.1.