No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

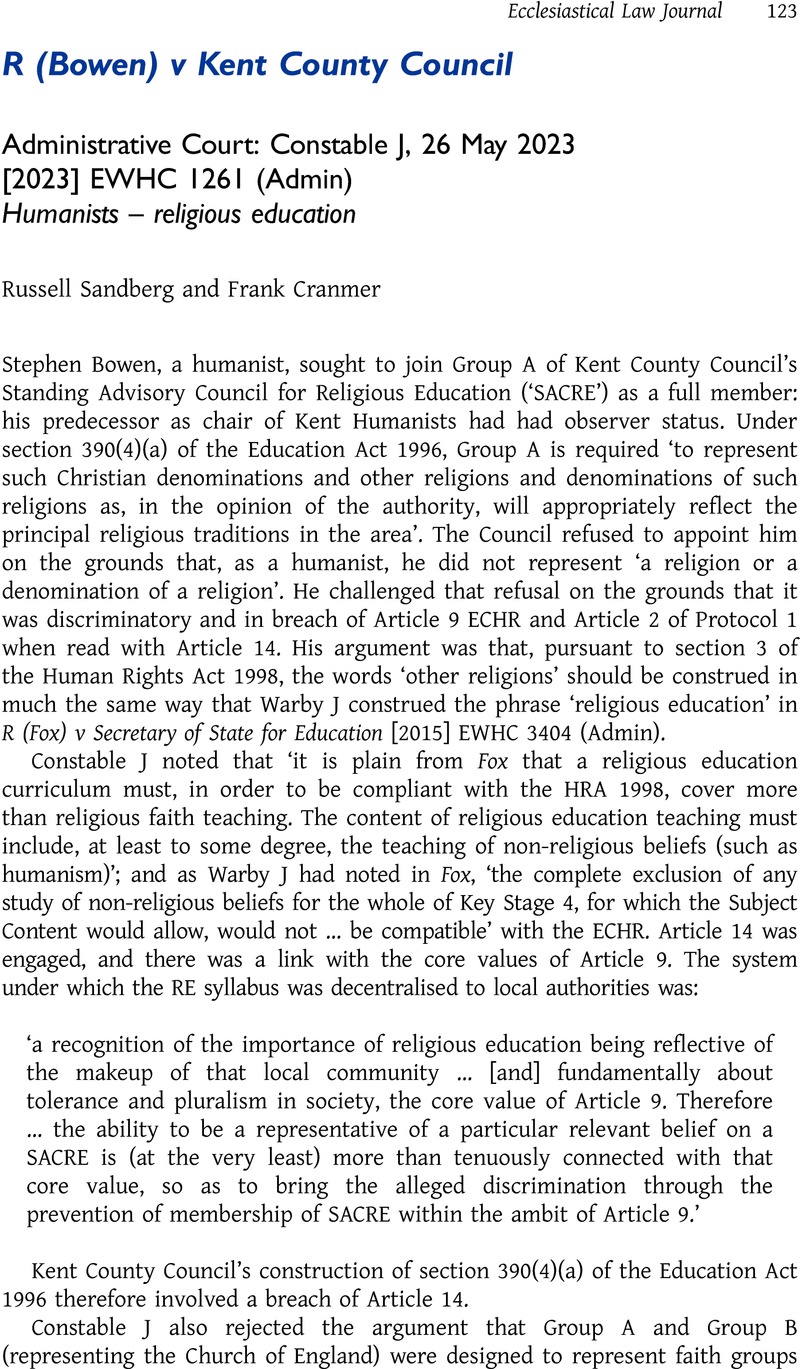

R (Bowen) v Kent County Council

Administrative Court: Constable J, 26 May 2023[2023] EWHC 1261 (Admin)Humanists – religious education

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 January 2024

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Case Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Ecclesiastical Law Society 2024