Background

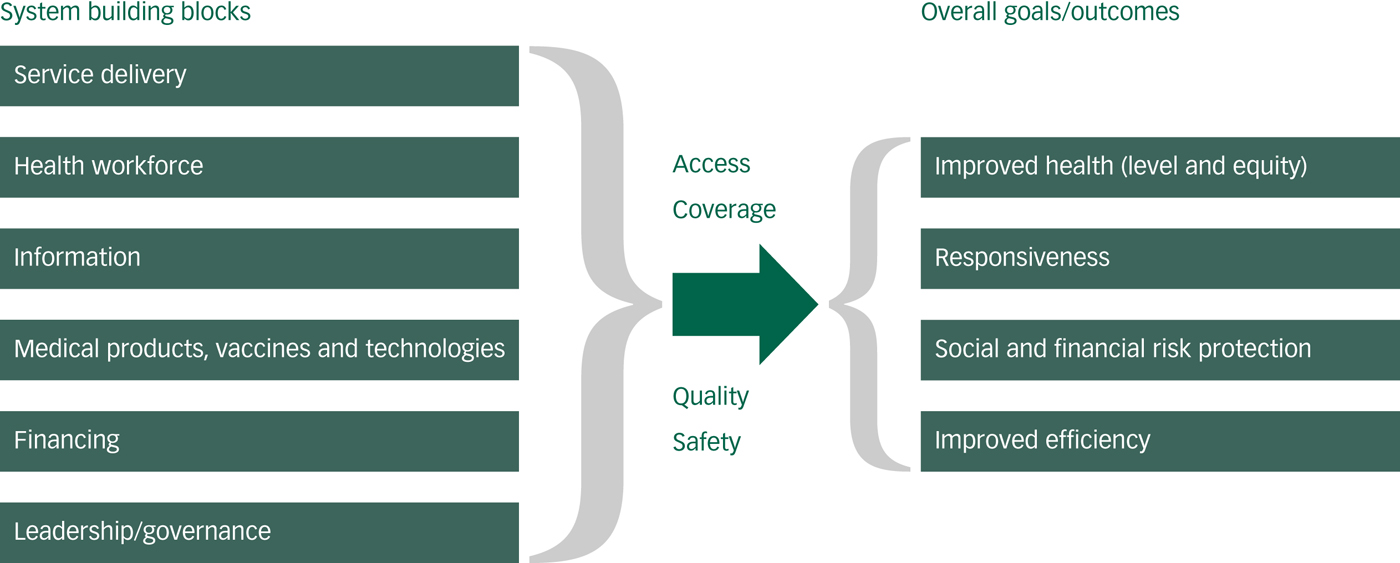

This thematic series in BJPsych Open reports on the work and findings of the Emerald (Emerging mental health systems in low- and middle-income countries) programme.Reference Semrau, Evans-Lacko, Alem, Ayuso-Mateos, Chisholm and Gureje1 Emerald was funded over 5 years (2012–2017) by the European Union's 7th framework programme to support health system strengthening research related to mental health. In this context a health system is defined as ‘the sum total of all the organizations, institutions and resources whose primary purpose is to improve health’2 within which the World Health Organization (WHO) has identified six core system components (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 The World Health Organization (WHO) health system framework (figure); page 3, 2007. Everybody's Business – Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO's Framework for Action. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf.

The challenge

At present, health systems fail people with mental disorders in every country worldwide. At best only a third of people with mental disorders are treated in some high-income countries, and at worst fewer than 5% of people with mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) receive any treatment or care.Reference Thornicroft, Chatterji, Evans-Lacko, Gruber, Sampson and Aguilar-Gaxiola3–Reference Wang, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Angermeyer, Borges and Bromet6 This large disparity between true levels of need and actual treatment rates is referred to as the ‘treatment gap’. This gap is due, in part, to the substantial under-resourcing for mental health, which results in far too few human resources for mental health and a reliance on a small number of beds in tertiary hospitals. Stigma and discrimination may also contribute to the treatment gap because people do not access services or are exposed to human rights abuses. The gap exists even though the substantial contribution of mental disorders to the global burden of disease is increasingly recognised,Reference Whiteford, Ferrari, Degenhardt, Feigin and Vos7, Reference Vigo, Thornicroft and Atun8 as well as their cross-cultural applicability and relevance to sustainable development.Reference Patel, Saxena, Frankish and Boyce9, Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana and Bolton10 Although there are now several high-quality sources that synthesise information on effective interventions for people with mental disorders,11–Reference Patel, Chisholm, Parikh, Charlson, Degenhardt and Dua13 far less developed is our understanding of what elements must be put in place at the national, regional and community levels to support the long-term delivery of effective mental health services.Reference Petersen, Evans-Lacko, Semrau, Barry, Chisholm, Gronholm, Patel, Chisholm, Dua, Laxminarayan and Medina-Mora14, Reference Petersen, Marais, Abdulmalik, Ahuja, Alem and Chisholm15

The aims of the Emerald programme were to improve mental health outcomes in six LMICs (Ethiopia, India, Nepal, Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda) by building capacity and by generating evidence to enhance health system strengthening, thereby improving mental healthcare and so contributing to a reduction in the mental health treatment gap. The key characteristics of the six Emerald country sites are shown in Table 1. These countries all face the formidable mental health system challenges that are common across LMICs, such as weak governance, a low resource base and poor information systems. The six countries were invited into the programme as a result of the commitment of local researchers and policymakers to engage in this programme, and to provide a rich comparison of sites in relation to their geographical, economic, sociocultural and urban/rural contexts, in order to strengthen the generalisability of the findings.

The five components of the Emerald programme

The Emerald programme entailed the coordination of the following five components (called work packages).

Capacity building

This work by Sara Evans-Lacko, Charlotte Hanlon, Atalay Alem and colleagues is described in paper two of this BJPsych Open thematic series,Reference Evans-Lacko, Hanlon, Alem, Ayuso-Mateos, Chisholm and Gureje18 which builds upon previous reports.Reference Thornicroft, Cooper, Van Bortel, Kakuma and Lund19–Reference Samudre, Shidhaye, Ahuja, Nanda, Khan and Evans-Lacko26 The Emerald programme has successfully supported the doctoral (PhD) studies of ten students across the six LMICs (three from Ethiopia, two from India, one from Nepal, one from Nigeria, two from South Africa, one from the UK). In addition, three Masters-level teaching modules with 28 submodules (see Appendix) have been developed that can be integrated into ongoing Masters courses, as well as three short courses for: (a) researchers; (b) policymakers and planners; and (c) patients and caregivers, to build capacity in mental health systems research within Emerald countries and beyond. These training materials are available for open access to relevant staff in countries worldwide using a Creative Commons licence.

Mental health financing

Paper three in this BJPsych Open thematic series considers strategies for sustainable mental health system financing in LMICs,Reference Chisholm, Docrat, Abdulmalik, Alem, Gureje and Gurung27 led by Dan Chisholm, Crick Lund and Sumaiyah Docrat.Reference Chisholm, Burman-Roy, Fekadu, Kathree, Kizza and Luitel28–Reference Chisholm, Heslin, Docrat, Nanda, Shidhaye and Upadhaya30

Integrated care

Within Emerald, we have deliberately approached the scaling up of services to identify and treat many more people with mental disorders in LMICs by integrating these activities into mainstream primary and community healthcare services. Paper four in this seriesReference Petersen, van Rensburg, Kigozi, Semrau, Hanlon and Fekadu31 is coordinated by Inge Petersen and Fred Kigozi, and discusses the key barriers and facilitators related to such integrated care.Reference Petersen, Evans-Lacko, Semrau, Barry, Chisholm, Gronholm, Patel, Chisholm, Dua, Laxminarayan and Medina-Mora14, Reference Marais and Petersen32–Reference Upadhaya, Jordans, Pokhrel, Gurung, Adhikari and Petersen36

Mental health information systems

Knowledge of how health systems perform, in order to manage and improve them, is crucial yet such data are most often missing, scarce or of poor quality in LMICs. Paper five in this series led by Mark Jordans and Oye Gureje describes the practical utility of new mental health system indicators developed by the Emerald team,Reference Jordans, Chisholm, Semrau, Gurung, Abdulmalik and Ahuja37 and paper six led by Shalini AhujaReference Ahuja, Hanlon, Chisholm, Semrau, Gurung and Abdulmalik38 sets out our findings of how such indicators can best be implemented.Reference Jordans, Chisholm, Semrau, Upadhaya, Abdulmalik and Ahuja39, Reference Upadhaya, Jordans, Abdulmalik, Ahuja, Alem and Hanlon40

Recommendations paper

Although the evidence generated by programmes such as Emerald can make original contributions to the scientific literature, more important is whether such information is actionable, namely can be communicated to those who are in a position to practically apply this information to improve treatment and care. José Luis Ayuso-Mateos and colleagues set out in paper seven what has been learned within Emerald on how to successfully achieve such forms of knowledge transfer.Reference Ayuso-Mateos, Miret, Lopez-Garcia, Alem, Chisholm and Gureje41

In our conclusion, paper eight presents a series of recommendations by the Emerald team for the strengthening of mental health systems in LMICs, taking a cross-cutting approach over the five different work packages that were implemented during the programme.Reference Semrau, Alem, Ayuso-Mateos, Chisholm, Gureje and Hanlon42

Conclusions

The field of global mental health is now undergoing a remarkable transformation with a long overdue appreciation of the scale of the contribution of mental disorders to the global burden of disease,Reference Vigo, Thornicroft and Atun8, Reference Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, Ferrari and Erskine43 and the potential for greater community cohesion and workplace productivity if people with these conditions are properly treated and supported. The inclusion of clear mental-health-related targets and indicators within the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals44–Reference Thornicroft and Votruba46 now intensifies the need for strong evidence about both how to provide effective treatments, and how to deliver these treatments within robust health systems.

Table 1 Indicators of development, health resources and the mental health system in the Emerald country sites

Source: Originally published in Semrau et al Reference Semrau, Evans-Lacko, Alem, Ayuso-Mateos, Chisholm and Gureje1 Data taken from the World Health Organization (WHO)'s Mental Health Atlas 16 and WHO's AIMS.17

Funding

The research leading to these results was funded by the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement number 305968. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. G.T. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) South London and by the NIHR Applied Research Centre (ARC) at King’s College London NHS Foundation Trust, and the NIHR Applied Research and the NIHR Asset Global Health Unit award. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. G.T. receives support from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01MH100470 (Cobalt study). G.T. is supported by the UK Medical Research Council in relation the Emilia (MR/S001255/1) and Indigo Partnership (MR/R023697/1) awards. M.S. is supported by the NIHR Global Health Research Unit for Neglected Tropical Diseases at the Brighton and Sussex Medical School.

Acknowledgements

The partner organisations involved in Emerald were Addis Ababa University (AAU), Ethiopia; Butabika National Mental Hospital (BNH), Uganda; ARTTIC, Germany; HealthNet TPO, Netherlands; King's College London (KCL), UK; Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI), India; Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Nepal (TPO Nepal), Nepal; Universidad Autonoma de Madrid (UAM), Spain; University of Cape Town (UCT), South Africa; University of Ibadan (UI), Nigeria; University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), South Africa; and World Health Organization (WHO), Switzerland.

The Emerald programme was led by Professor Graham Thornicroft at KCL. The project coordination group consisted of Professor Atalay Alem (AAU), Professor José Luis Ayuso-Mateos (UAM), Dr Dan Chisholm (WHO), Dr Stefanie Fülöp (ARTTIC), Professor Oye Gureje (UI), Dr Charlotte Hanlon (AAU), Dr Mark Jordans (HealthNet TPO; TPO Nepal; KCL), Dr Fred Kigozi (BNH), Professor Crick Lund (UCT), Professor Inge Petersen (UKZN), Dr Rahul Shidhaye (PHFI) and Professor Graham Thornicroft (KCL).

Parts of the programme were also coordinated by Ms Shalini Ahuja (PHFI), Dr Jibril Omuya Abdulmalik (UI), Ms Kelly Davies (KCL), Ms Sumaiyah Docrat (UCT), Dr Catherine Egbe (UKZN), Dr Sara Evans-Lacko (KCL), Dr Margaret Heslin (KCL), Dr Dorothy Kizza (BNH), Ms Lola Kola (UI), Dr Heidi Lempp (KCL), Dr Pilar López (UAM), Ms Debra Marais (UKZN), Ms Blanca Mellor (UAM), Mr Durgadas Menon (PHFI), Dr James Mugisha (BNH), Ms Sharmishtha Nanda (PHFI), Dr Anita Patel (KCL), Ms Shoba Raja (BasicNeeds, India; KCL), Dr Maya Semrau (KCL), Mr Joshua Ssebunya (BNH), Mr Yomi Taiwo (UI) and Mr Nawaraj Upadhaya (TPO Nepal).

The Emerald programme's scientific advisory board included A/Professor Susan Cleary (UCT), Dr Derege Kebede (WHO, Regional Office for Africa), Professor Harry Minas (University of Melbourne, Australia), Mr Patrick Onyango (TPO Uganda), Professor Jose Luis Salvador Carulla (University of Sydney, Australia), and Dr R Thara (Schizophrenia Research Foundation (SCARF), India).

The following individuals were members of the Emerald consortium: Dr Kazeem Adebayo (UI), Ms Jennifer Agha (KCL), Ms Ainali Aikaterini (WHO), Dr Gunilla Backman (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; KCL), Mr Piet Barnard (UCT), Dr Harriet Birabwa (BNH), Ms Erica Breuer (UCT), Mr Shveta Budhraja (PHFI), Amit Chaturvedi (PHFI), Mr Daniel Chekol (AAU), Mr Naadir Daniels (UCT), Mr Bishwa Dunghana (TPO Nepal), Ms Gillian Hanslo (UCT), Ms Edith Kasinga (UCT), Ms Tasneem Kathree (UKZN), Mr Suraj Koirala (TPO Nepal), Professor Ivan Komproe (HealthNet TPO), Dr Mirja Koschorke (KCL), Mr Domenico Lalli (European Commission), Mr Nagendra Luitel (TPO Nepal), Dr David McDaid (KCL), Ms Immaculate Nantongo (BNH), Dr Sheila Ndyanabangi (BNH), Dr Bibilola Oladeji (UI), Professor Vikram Patel (KCL), Ms Louise Pratt (KCL), Professor Martin Prince (KCL), Ms M Miret (UAM), Ms Warda Sablay (UCT), Mr Bunmi Salako (UI), Dr Tatiana Taylor Salisbury (KCL), Dr Shekhar Saxena (WHO), Ms One Selohilwe (UKZN), Dr Ursula Stangel (GABO:mi), Professor Mark Tomlinson (UCT), Dr Abebaw Fekadu (AAU) and Ms Elaine Webb (KCL).

Appendix

Masters-level teaching modules in health system strengthening developed by Emerald (Source: originally published in Semrau et al)Reference Semrau, Evans-Lacko, Alem, Ayuso-Mateos, Chisholm and Gureje1

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.