The concept of change has become a common topic of discussion within both the health service and higher education. Service provision and points of contact have shifted significantly within both sectors, and those with a foot in both camps need to negotiate and understand change that can occur simultaneously within, as well as independently of, each sector. For staff working in mental health services who contribute to teaching, the impact of these changes has become significant.

The delivery of mental health services in high-resource countries, as proposed by the World Health Organization (2001a , b ), is shifting towards a balanced-care model. Within such a model the aim is to move from hospital-based services to service provision in the community and to strike a balance between hospital and community care. Both the available evidence and accumulated clinical experience support this balanced approach (Reference Thornicroft and TansellaThornicroft & Tansella, 2003, Reference Thornicroft and Tansella2004).

Over the past 10 years, the quality enhancement agenda in higher education has focused heavily on teaching and learning. In its 2003 White Paper The Future of Higher Education, the government suggested the need for higher education institutions to go further and consider how they will improve and monitor their provision because ‘all students are entitled to high quality teaching’ (Department for Education and Skills, 2003: p. 46).

Generic changes can be witnessed across both sectors in terms of rising student and patient numbers, increased accountability, greater scrutiny, increased managerialism and technological developments. Current work under the Modernising Medical Careers initiative (http://www.mmc.nhs.uk/pages/home) and the Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board (PMETB; http://www.pmetb.org.uk/) have given further stimulation to the development of standards. Both have focused on the quality of training and the learning experiences of current and future doctors.

Such changes have implications for teaching staff, who must give formal consideration to how best trainees (particularly medical students and junior doctors in training) can be offered learning opportunities in community-oriented psychiatry. Effectively incorporating the experiences available from community psychiatry into the curriculum may be useful in reversing some of the negative views trainees appear to have of their time studying psychiatry. Modernising Medical Careers argues for the development of academic programmes ‘through imaginative approaches including collaborations’ (Modernising Medical Careers & UK Clinical Research Collaboration, 2005: p. 16). The curriculum can incorporate learning opportunities arising during domiciliary visits, working with a variety of agencies, making joint assessments and understanding the role of different community services. These experiences need to be mapped to the skills and competencies that trainees need to acquire and demonstrate, such as taking a proper psychiatric history, assessment and formulation. This will be effective only if the teaching and learning strategies currently used are examined and made responsive to the opportunities offered by community psychiatry and to the learning styles of the trainees.

The main purpose of this article is to stimulate further discussion in the hope of initiating a process to review training needs, identify current issues and look at how we could bring about change in teaching that stimulates and promotes effective learning. As the Modernising Medical Careers initiative continues to develop it is important for those within specialist services to take a constructive look at the opportunities that their specialties may have to offer.

The changing learning environment

The effect of increasing student numbers as individuals are encouraged to enter higher education from non-traditional backgrounds has been a change from an elite to a mass education system (Reference LandLand, 2004). Medical teaching staff find themselves under pressure to accommodate more students at a time when the pressure on services is also growing. Demands on time and resources increase proportionately. The Modernising Medical Careers initiative has recognised that education and training have not featured strongly among National Health Service (NHS) goals and that there has been a decline in the number of academic staff available to teach psychiatry.

Increased scrutiny of doctors’ activity, including teaching, has grown in line with the current ‘audit culture’ and increased managerial intervention. As Reference Kinman and JonesKinman & Jones (2004) argue in their survey of stress and the work–life balance in higher education, a major contributing factor has been greater bureaucracy. The increased managerialism goes hand in hand with increasing accountability. A quick look at the NHS website (http://www.nhs.uk) reveals an extensive range of performance indicators. Under ‘performance indicators for mental health trusts’ are listed 28 different indicators. Modernising Medical Careers also suggests that it will provide ‘explicit standards of assessed competence’ (National Health Service, 2005). PMETB has 18 criteria governing applications to the Specialist Register, with a range of corresponding standards for psychiatry. A check on the websites of the Higher Education Statistics Agency (http://www.hesa.ac.uk) or the Higher Education Funding Council for England (http://www.hefce.ac.uk) shows that performance indicators for teaching activities have been in development since 1998 and they are now being published (the most recent in December 2004). These indicators provide comparative data on the performance of institutions in broadening access to higher education, student retention, learning and teaching outcomes, research output and graduate employment that can be used to ensure a greater public accountability of the sector (Higher Education Statistics Agency, 2004).

Technological progress has provided universities and hospitals with a range of new equipment that potentially alters the learning environment. Traditional teaching methods have come under pressure as students and managers demand change. Universities and hospitals no longer serve just their local community – they serve a potentially global market. Discourses here surround such issues as access, flexibility, diversity and increased opportunity to provide appropriate situations for learning. These have to be offset by economic pressures such as the space available for learning both in physical terms and in timetabling, availability of teaching staff and service requirements.

Teaching psychiatry – the need to embrace change

Revisiting a 1966 survey 20 years later Reference Daniel, Clopton and Castelnuove-TedescoDaniel et al(1990) concluded that ‘psychiatry continued to be regarded as the most poorly taught and the least well learned subject in medical school’. Nearly 10 years on Reference Goerg, de Saussure and GuimonGoerg et al(1999) suggested that again not much had changed: ‘students tend to give fairly low ratings overall’. As Goerg et al point out, the teaching of psychiatry in medical schools has to ensure basic training for all students and entice some into choosing psychiatry as their specialty. Reference Baxter, Singh and StandenBaxter et al(2001) found that the change that occurs in medical students in favour of psychiatry, psychiatrists and mental illness after their fourth year of psychiatric training is transient and decays over the final year.

Change to the curriculum appears overdue. Indeed, Modernising Medical Careers urges psychiatry to

‘nurture educationalists who will contribute to and lead curriculum design, revision and implementation, assessment and programme quality assurance’ (Modernising Medical Careers & UK Clinical Research Collaboration, 2005: p. 16).

Reference ColesColes (1993) has argued that teaching methods need to be aligned much more closely with aims and objectives that take account of the principles of teaching adults. This view has been recognised for some time by many in medical education. The Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education suggested in 1999 that ‘a broader view of teaching and what counts as education has emerged’ (Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education, 1999: p. 30).

As mentioned above, the change in the provision and pattern of services available has added complexity to the learning environment as well as to the knowledge, skills and attitudes that are required of trainees. Reference FranksFranks (2000) has written that undergraduate medical training in the UK is undergoing a profound change in which the traditional didactic approach is being replaced by topic- and problem-based teaching that encourages greater student participation and independent learning. Unfortunately, according to Reference O'Connor, Clarke and PresnellO’Connor et al(1999) and Reference Vassilas, Brown and WallVassilas et al(2003) recommendations and comments by such as Modernising Medical Careers and Coles have had little effect on the teaching of psychiatry. They report that, although literature exists that reflects the interface of psychiatry and education, until now there has been little with specific regard to teaching psychiatrists teaching and learning skills.

Teaching in psychiatry has yet fully to acknowledge the developments in medical education that have seen much traditional teaching transformed and replaced by new methods. A number of writers have suggested a series of teaching strategies that might be of benefit (Reference Factor, Stein and DiamondFactor et al, 1988; Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 1997). Community psychiatry, because of the nature of the environment within which it operates, offers opportunities to develop the curriculum away from the traditionally passive learning now much criticised by students and educators alike.

Knowledge, attitude and skills –the role of community psychiatry

Community psychiatry has been defined as

‘the network of services which offer continuing treatment, accommodation, occupation and social support and which together help people with mental health problems to regain their normal social roles’ (Reference Strathdee, Thornicroft, Murray, Hill and McGuffinStrathdee & Thornicroft, 1997: p. 514).

The current trend is for nearly all psychiatric sub-specialties to include substantial periods of work outside the hospital. Community psychiatry therefore has the potential to enhance students’ knowledge, skills and attitudes. If offers opportunities for the development of the skills needed to work with a range of professionals and patients in different settings.

Given the profound impact of mental health disorders on public health (Reference Murray and LopezMurray & Lopez, 1996; World Health Organization, 2001b ) there is an obligation to ensure that the learning provided enables trainees to develop their understanding effectively. Currently, however, the shift to the balanced-care model recommended by the World Health Organization has not been very clearly reflected in the training curriculum and there is a need to consider how to incorporate community psychiatry more effectively within the curriculum for medical students and junior doctors in training.

As PMETB establishes and refines the standards and requirements of postgraduate medical education and training, so Modernising Medical Careers calls for greater cooperation with universities to develop dedicated academic training programmes (Modernising Medical Careers & UK Clinical Research Collaboration, 2005: p. 4). Such developments bring with them additional requirements of organisations such as the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, which publishes a range of benchmark statements for undergraduate medicine. For example, graduates are required to be able to make decisions in partnership with colleagues and patients (Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, 2002: p. 6). Community psychiatry offers trainees the opportunity of working towards this benchmark by developing their knowledge of the roles of the professionals within community mental health teams: community psychiatric nurses, occupational therapists, psychologists, social workers, support workers and other professionals. The shift towards the balanced-care model therefore offers teaching staff the opportunity to make use of working collaboratively. The model emphasises a move from ‘control’ to ‘collaboration’ (Reference Johnston, Binder and FreelandJohnston et al, 1995). Trainees need to understand and appreciate how to develop effective working relationships with others involved in the care of patients in the community.

To enable trainees to understand the learning environment offered by community psychiatry, effective supervision is vital. Through supervision, the teaching team can develop trainees’ understanding of the key considerations within the community setting (Box 1). Trainees can develop their knowledge of strategies for relapse prevention and a clear understanding of the biopsychosocial model. It is also important to appreciate the influence of adverse social circumstances and to gain skills in liaison with the voluntary sector, local agencies and other related organisations.

Box 1 Supervision

Trainees should have adequate supervision in:

-

• domiciliary visits

-

• joint assessments with other professionals of the team

-

• understanding of the work of different community services, e.g. assertive outreach, crisis intervention services, home treatment teams

-

• liaison with primary care

-

• understanding of other agencies, particularly hostels and supported accommodation

An attribute of paramount importance is an appropriate attitude. This can be difficult to instil in trainees, especially as contact time is often limited. Role modelling is therefore important and trainees need to spend time with staff in out-patient clinics, accompanying them on community visits and sitting in on case conferences, care programme approach meetings and other multi-disciplinary meetings. This exposure can help trainees appreciate the benefits of setting realistic goals and sharing relevant information with appropriate agencies, and the importance of maintaining confidentiality while being open to discussions with others involved in a patient’s care. Action to change attitudes might include learning how to enhance public education and deal with stigma (Department of Health, 1999).

In his report on the first 5 years of the National Service Framework Louis Appleby, the National Director for Mental Health, stated that the focus had largely been on improving specialist care, including the development of specialist community mental health teams offering home treatment, early intervention services and intensive support for people with the most complex needs (Reference ApplebyAppleby, 2004). The next 5 years, he wrote, will see this focus widen to look at the mental health needs of the community as a whole. He also mentioned the need to tackle the social exclusion of people with mental health problems, improving their employment prospects and opposing stigma and discrimination.

Trainees working in community psychiatry can expect to assess patients in a variety of settings, including out-patient clinics, patients’ homes, hostels, general practitioner’s surgeries and police stations. The skills required for this can be demanding, and trainees also need to develop the confidence to express their knowledge and concerns (Box 2). The curriculum and the teaching and learning strategies employed to support it should focus on enabling trainees to obtain a precise focused history, undertake a mental state examination, understand complex needs, be aware of risk factors and take due consideration of their own safety. Trainees also need to acquire the skill of case-load management.

Box 2 Skills and competencies of community psychiatry

Trainees need to:

-

• understand the importance of obtaining a proper psychiatric history

-

• know how to do a mental state examination

-

• understand biopsychosocial factors in the aetiology and management of mental illness

-

• be aware of personal safety and security issues

-

• understand the importance of confidentiality and its intricacies for patients seen in a community setting

-

• be able to assess and manage risk in the context of community care

-

• have a broad understanding of the Mental Health Act 1983

-

• develop appropriate communication skills

-

• have a basic understanding of psycho-pharmacology and the principles of psychological therapies

-

• understand the importance of and be competent in liaison with other agencies

Opportunities offered by community psychiatry

Community psychiatry offers trainees a unique insight into the delivery of services that also reflects the values of PMETB (Box 3). They have the opportunity to observe and engage in collaboration, negotiation and discussion with a range of agencies and individuals. They can also observe clients in different settings and become more aware of issues in situ. Trainees can witness the complications as well as the opportunities that the community setting can provide.

Box 3 Links between community psychiatry and PMETB values

-

• Independence – the community setting develops independence through a process of observation and personal experience

-

• Collaboration and inclusiveness – trainees need to work in collaboration and develop skills in negotiation and inclusion

-

• Responsiveness – the community setting provides trainees with an ideal opportunity to experience and respond to a range of issues and develop effective strategies based on that experience

-

• Diversity and opportunities for all – those working in the community are constantly engaged with issues relating to access and opportunity

The opportunity to interact with a range of professionals in community psychiatry, combined with their training in a hospital setting, gives medical students a better chance to gather greater understanding of the discipline and some of its complexities. One aim of the Modernising Medical Careers project is to create doctors who are skilled communicators and can work as effective members of a team. Community psychiatry offers an ideal environment for this.

Working in direct contact with specialist community psychiatrists allows feedback on real experiences that are more likely to have significant impact on trainees. Theory is linked very closely with practice and becomes less abstract. Feedback, always crucial for learners, can be individual and immediate. Trainees who have a more individual learning style may find that the community setting suits them better than the hospital.

Difficulties to be addressed in the curriculum

To ensure that the curriculum builds on the benefits of training via community psychiatry it is important to recognise the potential difficulties of the setting. Community mental health centres are usually situated away from main hospital bases and academic institutions, and it is common for trainees working at such dispersed sites to experience feelings of isolation and a subsequent loss of peer support (Reference Davies and CoxDavies & Cox, 1996). For some this poses minimal problems and is indeed beneficial. However, it is important that systems are put in place to enable trainees to be monitored to ensure the early identification of any problems. Setting clear objectives and boundaries at the beginning of a placement can be effective in starting this process.

Logistics

There are also logistical difficulties to consider. To ensure that trainees feel as integrated as possible during their placement it is important that roles and responsibilities are clear. At a very practical level, trainees must be made aware that many centres have restricted parking and they need to allow for this if they are to attend punctually. The community placement can present added complications in terms of travel time. These issues can be used to teach trainees the importance of time management.

Contact

Within a busy community setting it might sometimes be difficult to incorporate protected time for the trainee, for example because of emergencies. Uncertainty can therefore linger and hinder effective learning. There are constraints on space, and the learning environment for trainees is often far from ideal. As a result trainees may feel that they are not valued, that they have little part to play in the team or that their learning lacks meaningful context. It is therefore important that trainees encounter at the outset of a placement teaching staff who are approachable, enthusiastic and willing to negotiate joint expectations (Reference RamsdenRamsden, 1992; Reference NichollsNicholls, 2002).

Safety is an important issue and the curriculum must make trainees aware of the dangers of community work and ready to arrange joint visits with other members of the team in certain situations. The curriculum should also identify the interface and need for liaison with primary care and other agencies serving the community, and reflect the conflicting demands of hospital and community work.

Feedback

The next issue to be addressed in the curriculum is assessment of learning through effective feedback. Reference MuijenMuijen (1993) stresses that assessment procedures are different in the community and that they require greater flexibility. Confidentiality is a particular problem, as it may be difficult to ensure privacy for client interviews, let alone for feedback to trainees. Feedback within a community setting can be daunting for the tutors, but the principles remain the same (Higher Education Academy, 2005). Ineffective communication and coordination of learning experiences by the wide range of professionals involved can easily reverse the learning benefits that trainees can gain.

Careful curriculum planning is required to enable trainees to learn effectively from their experiences in the variety of settings and from the numerous professionals that they are likely to meet in community psychiatry. For the best results feedback must be timely and the journey back to the office may be ideal for this, as long as confidentiality is ensured. Feedback must be relevant to the task in hand and to the student’s needs (Reference Juwah, Macfarlane-Dick and MatthewJuwah et al, 2004).

The shortage of placements

The curriculum should focus on providing trainees with experience of a range of interventions, developing new knowledge and understanding of other disciplines and organisations and intensive clinical community experience.

Inevitably the current system of placements cannot offer every trainee the opportunity to experience community psychiatry. Only some trainees are posted in community settings; the majority are posted solely in in-patient units. There are a variety of reasons for this: there are fewer community placements than students; the duration of posting does not offer the flexibility to combine a community placement with hospital work; the change in service delivery has contributed to the specialisation of psychiatrists either in community or in in-patient psychiatry and only a few trainers do both community and hospital work; and the pattern of service provision differs between trusts. It is important to acknowledge this and to ensure that experiences are shared whenever and wherever possible. Group tutorials can support peer learning and the sharing of experiences.

To ensure that trainees feel positive about their time in community psychiatry and psychiatry placements generally, the curriculum needs to address their problems as they arise (Box 4). Meeting the trainee regularly and revisiting key learning points are essential. Having a named contact or tutor during placements can assist in building up supportive relationships. This individual should be responsible for monitoring progress and ensuring that both the trainee and the professionals from the multidisciplinary team are included in the feedback loop. This tutor should take responsibility for ensuring that the trainee has the opportunities to acquire the skills listed in the core curriculum.

Box 4 Reducing the potential difficulties

The curriculum can be enhanced by:

-

• having a named tutor and contact throughout the placement

-

• developing clear, joint expectations of the placement and outcomes

-

• monitoring throughout the placement, involving both the trainee and other professionals

-

• ensuring timely and confidential feedback on progress

-

• highlighting the development of skills such as time management, as well as knowledge of course content

-

• ensuring that each trainee has specified time for contact with their tutor

An aligned curriculum

According to the Quality Assurance Agency’s subject benchmarks for medicine ‘medical curricula can be delivered in many ways’ (2002: p. 7). Although performance indicators exist – subject benchmark statements and a myriad of documents relating to standards and competencies – there appears to be little evidence on how to teach psychiatry effectively. According to Reference O'Connor, Clarke and PresnellO’Connor et al(1999), curricula should in theory be based on a detailed analysis of the knowledge and skills required by future general practitioners, physicians and surgeons.

However, change within mental health service delivery continues and new models of care and intervention may be introduced. Teaching staff must be aware of these and incorporate them into their teaching. A stark warning from Reference O'GradyO’Grady (1996) points to the danger that the pace of change within service delivery will outstrip the ability of training systems to deliver the consultants of the future.

When designing and evaluating the curriculum it is important to acknowledge and utilise the changes that are occurring within services. An almost exclusive exposure, for example, to patients in a hospital setting is unlikely to provide ‘sufficient knowledge and experience to equip (students) for their future careers’ (Reference HoughtonHoughton, 2005). As Reference ColesColes (1993) suggests, the curriculum needs to be effectively aligned, a notion that has been elaborated by Reference BiggsBiggs (1999).

Constructive alignment

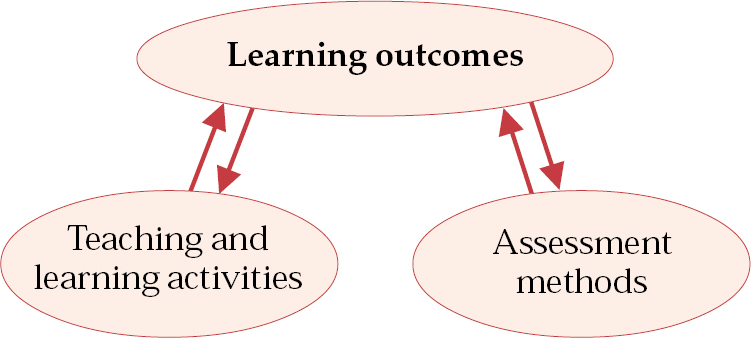

There are two key aspects of the ‘constructive alignment’ that Biggs coined. The first is that students construct meaning from what they learn. For learning to be effective the teacher therefore needs to plan learning activities that will enable the outcomes set to be achieved. The central parts of the process are the intended learning outcomes (Fig. 1). Once these are designated, teaching needs to achieve two things. The first is to create and develop learning activities that will help students to achieve these outcomes and the second is to implement assessment methods that truly evaluate the learning gained.

Although this model may appear to be simplistic, it is very difficult to achieve (Engineering Subject Centre, Higher Education Academy, 2005). The alignment relies on getting the trainee to take responsibility for the construction of their learning. The role of the teaching staff is to create an environment that encourages, enthuses and supports engagement so that the trainee takes this responsibility.

The learning outcomes expected of trainees have already been formulated. They are cited in the core curriculum for medical students and the Royal College of Psychiatrist’s curricula for doctors in training. In this article our main aim is to examine the strategies and assessment of the learning.

As people learn in different ways (Reference NichollsNicholls, 2002) a variety of teaching methods is needed to suit these differences. The broad structure of teaching sessions and topics should be planned with the trainees at the beginning of a placement. Trainees should be made aware of all the core curriculum topics to be covered. Such an approach ensures that all trainees are given the same information and are made aware of their responsibilities. Every effort should be made by the teacher to encourage deep rather than surface learning, and the teacher ’s enthusiasm is an important component of this (Reference ButcherButcher, 1995). The danger is that the increased pressures on teaching staff, the greater scrutiny and restrictions placed on them, will result in more not less reliance on formal didactic approaches rather than informal experiential opportunities (Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education, 1999).

Teaching methods

Evidence from a range of studies points to the advantages of certain teaching methods (Box 5). Staff teaching psychiatry need to consider how they can make effective use of these methods and in so doing improve alignment of the curriculum and allow the trainee to take responsibility for their learning.

Box 5 Effective teaching strategies to consider within community psychiatry

-

• Group supervision

-

• Collaborative, patient-focused learning

-

• Effective development of problem-based learning

-

• Use of a range of staff to provide learning input

Group supervision

The first method listed, group supervision, has been highlighted by Reference Factor, Stein and DiamondFactor et al(1988), who found that the supervision of trainees in small groups was a useful adjunct to one-to-one supervision. The advantage of group supervision is that it improves peer support, which is difficult to provide and maintain in dispersed placements. Group supervision offers trainees an opportunity to share experiences and learn from one another. It also has benefits for teaching staff, who can check consistency of understanding among a group of students rather than holding a series of individual meetings.

Collaborative, patient-focused learning

This second method that can support an aligned curriculum has been advocated by the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health (1997). This emphasises a training framework that is patient-focused, both theory- and practice-based and attributes great importance to collaborative training with other disciplines.

Medical students are faced with an enormous diversity of information and are often criticised for their inability to recognise links and synthesise one topic with another. Community psychiatry can emphasise the importance and benefits of working in collaboration with a range of groups and individuals, and the teaching can provide the stimulus for this. Trainees should be encouraged to draw on their wider knowledge and skills to collaborate effectively.

Problem-based learning

Problem-based learning in psychiatry has been advocated by a number of authors. Recent research comparing this method with traditional teaching found that the students following a problem-based curriculum achieved better clinical performance and acquired a stronger knowledge base (Reference McParland, Noble and LivingstonMcParland et al, 2004). Reference O'Connor, Clarke and PresnellO’Connor et al(1999) also highlighted the importance of broadening the clinical experience of students to better equip them for medical practice. Community psychiatry offers the opportunity for trainees to learn in a multidisciplinary context and provides a broad framework to enable rich and varied experiences to be offered.

Problem-based learning is liked by students and can be effective, but it can have drawbacks. Reference Bligh, Lloyd-Jones and SmithBligh et al(2000) found that new trainees often felt anxious about the clarity of objectives and the standard of work required. This is relevant within the community setting in light of the trainees’ potential isolation from peers. Teaching staff must recognise this and ensure that, through individual and group supervision, isolation is minimised, support is provided where available and concerns are addressed early on.

The final evidence is drawn from a study by Reference Hay and KatsikitisHay & Katsikitis (2001), who compared the outcomes of teaching in small groups by either an ‘expert’ or a ‘non-expert’ tutor in each topic/specialist area. Students who were taught by the expert scored higher in the end-of-course test in the topic area, but the non-expert tutors were rated highly for group management skills and they rated students more highly on oral communication.

A curriculum needs to take into account everyone who provides teaching, and community psychiatry offers the opportunity to add to the diversity of input of both specialists and non-specialists.

Assessment

Knowing that teaching has been effective, be it community- or hospital-based, is fundamental to curriculum development and is a key aspect of constructive alignment. The Modernising Medical Careers initiative is currently piloting a range of assessment tools (multi-source feedback, clinical evaluation exercise, direct observation of procedural skills and case-based discussion). It is important that learning is consolidated through an assessment strategy that allows students to demonstrate the knowledge and understanding they have gained from all the experiences they have encountered. This should include the aspects that are unique to the community setting.

Conclusions

It is acknowledged that one of the major difficulties facing the medical profession is the lack of clinical academics and there is clear evidence of a decline in the number of academic staff in psychiatry (Modernising Medical Careers & UK Clinical Research Collaboration, 2005). The Modernising Medical Careers initiative and the recommendations of PMETB highlight the need to do more to improve education and training. Psychiatry can benefit from these initiatives and can maximise these benefits by using all aspects that contribute to a balanced-care model within community services.

It is necessary to develop teaching methods appropriate to the current and ongoing trend of changes in service delivery. As the move continues towards community-oriented psychiatry, training must reflect this. Traditional medical attitudes and assumptions may be challenged. We should recognise and utilise the opportunities that our specialty offers trainees. Community psychiatry can provide students with the opportunity to work outside the hospital and see patients in their own environment, as well as to develop close liaison with primary care and related agencies in the community setting. Such opportunities are not often available to doctors in most other specialties. To maximise these positive opportunities the psychiatry curriculum needs to address the potential isolation of trainees, the demands of working in a variety of community settings and the possible conflict between community and hospital work. All of these can be turned into effective learning elements as trainees can witness the reality of clinical practice.

Teaching and learning are complex issues and within the diverse community setting can be difficult to integrate effectively. However, careful planning and attention to the issues outlined can ensure that this becomes a valuable experience for both the trainee and the team. It is crucial that trainees are integrated into the process at the outset and that they remain with a clear focus and able to communicate and gain feedback throughout.

Declaration of interest

None.

MCQs

-

1 The concept of change:

-

a is exclusive to health services

-

b is a common topic of discussion

-

c is exclusive to higher education

-

d is relevant in all areas and services

-

e has to be taken into consideration when addressing the varying trends.

-

-

2 In teaching community-oriented psychiatry to trainees:

-

a training should focus only on community-oriented psychiatry

-

b more emphasis needs to be given to knowledge

-

c surface learning should be encouraged

-

d care in both the hospital and the community setting should be integrated

-

e it is best to adopt didactic teaching methods.

-

-

3 The teaching and learning environment in a community setting provides:

-

a students with peer-group and peer support

-

b the opportunity to work in a variety of settings

-

c the potential to lay down a bedrock of psychiatric experience

-

d the opportunity for close liaison with primary care

-

e a greater diversity of learning.

-

-

4 Key considerations for teaching and learning in a community setting include:

-

a an emphasis on the formal didactic model

-

b the importance of team working

-

c interfaces with other teams and services

-

d time management

-

e understanding of the conflicting demands between hospital and community work.

-

-

5 Providing feedback to trainees in a community setting should:

-

a be as immediate as possible

-

b be confidential

-

c recognise that the principles of feedback are different in this setting

-

d be easier because of multidisciplinary working

-

e be constructive.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F | a | T |

| b | T | b | F | b | T | b | T | b | T |

| c | F | c | F | c | T | c | T | c | F |

| d | T | d | T | d | T | d | T | d | F |

| e | T | e | F | e | T | e | T | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.