Background to how dementia affects relationships

It is it, it is me, I am still me (long pause), somewhere. I'm glad you came because I'd forgotten about these places. (Georgia, co-researcher living with dementia)

The term dementia refers to different neurological conditions associated with deteriorating cognition, which can manifest as negative moods, emotions and changes in behavioural responses. Whilst specific dementias may present differently at first, over time, the degenerative condition can impact communication skills, decision making, mental health, memory and activities associated with daily living and, of course, relationships. Relationship roles and responsibilities can alter and the sense of companionship may be threatened (Hellström, Reference Hellström, Hyden, Lindemann and Brockmeier2014) as couples must adapt to constant changes which are often framed through the lens of loss (physical, mental and social loss) for the person living with the condition and their partner, and as a couple (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Boylstein and Zimmerman2009). The sense of ‘couplehood’ in terms of a shared sense of wellbeing (Hellström et al., Reference Hellström, Nolan and Lundh2007) can deteriorate (Davies, Reference Davies2011) when the partner becomes the carer and everyday life is dominated by the condition. Such relationship changes can cause depression, isolation and loneliness (Vikström et al., Reference Vikström, Josephsson, Stigsdotter-Neely and Nygård2008), and exacerbate cognitive deterioration for the person living with dementia (Kitwood, Reference Kitwood1997; de Vugt et al., Reference de Vugt, Stevens, Aalten, Lousberg, Jaspers, Winkens, Jolles and Verhey2003; Norton et al., Reference Norton, Piercy, Rabins, Green, Breitner, Østbye, Corcoran, Welsh-Bohmer, Lyketsos and Tschanz2009). Here the identities of both people (as individuals and as a couple) are likely to change as the daily dementia rhythm constrains their social lives (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Boylstein and Zimmerman2009). The complexity of changes cannot be underestimated as they fundamentally affect the closeness of the relationship (Pruchno et al., Reference Pruchno, Kleban, Michaels and Dempsey1990) and gender role expectations (Calsanti and King, Reference Calasanti and King2007).

Undoubtedly, couples experience multiple issues, frustrations and emotional ‘oscillations’ from negativity/depression to positive ‘highs’ (Boylstein and Hayes, Reference Boylstein and Hayes2012: 586). Depending on the premorbid relationship, there remains a ‘value of us’ where couples are able to stay living well together (Swall et al., Reference Swall, Williams and Marmstål Hammar2020: 4), and when supported by others the emotional and cognitive difficulties associated with the condition can be reduced (Van Assche et al., Reference Van Assche, Luyten, Van de Ven and Vandenbulcke2013; Balfour, Reference Balfour2014; Riley et al., Reference Riley, Evans and Oyebode2018; Conway et al., Reference Conway, Wolverson and Clarke2020). The potential for wellbeing and positivity (in them both) is more likely when the relationship is associated with participating in shared activities and not focusing exclusively on care-giving/receiving (Wadham et al., Reference Wadham, Simpson, Rust and Murray2016). Evidence reinforces the positive effects of psychosocial support and outcomes for wellbeing and quality of life (Sprange et al., Reference Sprange, Mountain, Shortland, Craig, Blackburn, Bowie, Harkness and Spencer2015; Nordheim et al., Reference Nordheim, Häusler, Yasar, Suhr, Kuhlmey, Rapp and Gellert2019). Activities that encourage couples to stay connected can enable them to live well at home together for longer (McGovern, Reference McGovern2011), but advice on how best to enact this and help the couple to communicate, meaningfully interact and find meaning in everyday life is vague (Ablitt et al., Reference Ablitt, Jones and Muers2009; Balfour, Reference Balfour2014; Bielsten and Hellström, Reference Bielsten and Hellström2019a, Reference Bielsten and Hellström2019b). Herein lies the practical and academic gap in knowledge.

Currently, few interventions that enhance dyadic relationships, where the couple are not reliant on professional facilitation or stressful journeys to/from clinic or hospital settings, have been tested (Bielsten et al., Reference Bielsten, Lasrado, Keady, Kullberg and Hellström2018). Such professional interventions and therapies reduce spontaneity and potential enjoyment for couples. Providing activities in the familiar home environment mediates such emotional negativity whilst actively stimulating the wellbeing of the couple (Bielsten et al., Reference Bielsten, Lasrado, Keady, Kullberg and Hellström2018). Also, studies show that community group interactions in local environments can lead to sustainable relationships and enhance their own sense of self and identity (Davies-Quarrell et al., Reference Davies-Quarrell, Higgins, Higgins, Quinn, Quinn, Jones, Jones, Foy, Foy, Marland and Marland2010; Hampson and Morris, Reference Hampson and Morris2016). The COVID-19 pandemic has increased homebound isolation, inhibiting meeting family members, friends and community interaction, which increases the importance of support options than can be jointly undertaken at home. Here, the suitcase of memories (SOM) approach can fill this gap and help provide enjoyable distraction from the stresses of the condition and to encourage sharing of positive experiences whilst at home. This individualised multisensory reminiscence toolkit focused on the reliving of shared holiday memories between the person living with dementia and their partner. SOM included the creation of a digital film from the couple's photographs with accompanied soundscapes to enhance the experience and overcome difficulties associated with vision. The SOM also allowed for exploration and re-enactment with their souvenirs, holiday artefacts and clothing, and the sharing of tastes and smells of food and drink associated with these holiday memories.

The role of meaningful activities with people living with dementia

The value of engaging in meaningful activities has positive benefits for people living with dementia (Brooker et al., Reference Brooker, Woolley and Lee2007; Nyman and Szymczynska, Reference Nyman and Szymczynska2016), especially those enhancing a feeling of wellbeing through sensory stimulation (Treadaway et al., Reference Treadaway, Kenning and Coleman2014) and those that include reminiscence stimulated by the creative arts. Reminiscence is associated with improved cognition, memory and communication between the couple and their extended family (Bruce and Schweitzer, Reference Bruce, Schweitzer, Downs and Bowers2014; Guendouzi et al., Reference Guendouzi, Davis and Maclagan2015; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Chen, Chen, Hu, Liu, Kuo and Chiu2015). Such shared activities have been correlated with positive wellbeing (Dempsey et al., Reference Dempsey, Murphy, Cooney, Casey, O'Shea, Devane, Jordan and Hunter2014) and result in resilient relationships (Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Hunter, Murphy, Casey, Devane, Smyth, Dempsey, Murphy, Jordan and O'Shea2014; Gonzalez et al., Reference Gonzalez, Mayordomo, Torres, Sales and Meléndez2015). Advances in multimedia technology also provide new modes for sensory stimulation, especially for recalling positive memories (reducing the effects of social isolation) and simultaneously stimulating communication between couples (McHugh et al., Reference McHugh, Wherton, Prendergast and Lawlor2012). Multimedia technology-enabled activities have been used to facilitate reminiscence, but are limited in application and based largely on hearing and visual senses in isolation. These interactions are relatively sedentary in nature and missing the health and psychological benefits of embodied encounters that encourage movement (Bejan et al., Reference Bejan, Gündogdu, Butz, Müller, Kunze and König2018); whereas the SOM was designed to encourage naturally evolving embodied experiences. In doing so, the recall of enjoyable memories between the couple contributed to their wellbeing, especially when taste and smell were stimulated.

The SOM was designed as a shared activity to enhance reminiscence by stimulating a wider variety of senses (taste, smells, touch, sounds, re-enactment and movement) including hearing and sight. Studies prove that odours can help recall memories where participants have described a feeling of being ‘brought back’ to an experience (Herz and Schooler, Reference Herz and Schooler2002: 22) and evocatively stimulates the Proust phenomena (transporting people back in time evocatively through taste and smells), which is superior to using visual and language cues alone (Verbeek and van Campen, Reference Verbeek and van Campen2013). Recent research found people living with Alzheimer's disease preserved their sense of identity linked to positive emotions stimulated by olfactory reminiscence (Glachet and El Haj, Reference Glachet and El Haj2020). Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Frohlich, Alm and Vaughan2019) found soundscapes stimulated memory and emotions for people living with dementia, and dance and movement can have a positive effect on mood, concentration, communication and sense of wellbeing (Hamill et al., Reference Hamill, Smith and Röhricht2012). Whilst it is not proposed to over-stimulate a person living with dementia, the studies above highlight the importance of engaging in the senses to help with cognition and communication.

Combined sensory stimulation positively influences the health and social needs of both the person who has dementia and their partner, and supports the couple living at home. The supporting research for SOM draws on stories of people living with moderate dementia and their partners to gain insight into the role that multisensory reminiscence can play in enhancing their lives and relationships. The focus of SOM is the stimulation of holiday and tourism-related memories which stimulate senses and positive shared experiences.

Aim of the study

The study aims to explore the meaning and significance of recalling tourism memories for couples living with moderate dementia. SOM uses multisensory reminiscence, as holidays are usually associated with pleasurable times and multiple sensations that affected the couple at the time (heat, smells, etc.). The research extends the results of a first phase involving conversations exploring holiday memories with five people who had moderate dementia and their partners. The study also identified the practical challenges when researching with individuals with language and cognitive problems, especially when using methods that rely on verbal communication. To overcome these difficulties, photographs were used to trigger memories, however, some of the participants struggled visually (due to the dementia and increasing age), rendering photographic stimulation problematic, and revealed a need to introduce other means of communication. Further challenges resulted from analysing frequently inaudible audio recordings as participants struggled to complete their sentences and articulate their responses due to their dementia, highlighting the need for more innovative non-traditional research methods to accompany these conversations. Upon researcher reflection, the need for interactive, multisensory approaches where the person was immersed in and had a greater sense of involvement in the research was identified.

In contrast to the conversations with the people living with dementia, where themes of ‘memories as embodied experiences’, ‘nostalgia’ and ‘holidays in time and place’ reflected on the past and positive aspects of recalling holidays, their partners focused on the present day and themes of ‘loss and changing roles and relationships’, citing the need for ‘dementia-friendly holidays’. The disparity of the results between the participants who had dementia and their partners and the communication challenges experienced, along with evidence presented in the literature (Bruce and Schweitzer, Reference Bruce, Schweitzer, Downs and Bowers2014; Dempsey et al., Reference Dempsey, Murphy, Cooney, Casey, O'Shea, Devane, Jordan and Hunter2014; Guendouzi et al., Reference Guendouzi, Davis and Maclagan2015; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Chen, Chen, Hu, Liu, Kuo and Chiu2015), shaped the second phase: a suitcase of memories; the creation of a holiday-specific multisensory reminiscence that focused in depth on one couple's experience of recalling their shared holiday memories. This research was successful and resulted in A Suitcase of Memories: A Sensory Ethnography of Tourism and Dementia with Older People (Mullins, Reference Mullins2018). Holidays and tourism play a large part in forming happy memorable experiences/neural connections for most people, that are reconstructed as stories over time and can impact on self and identity (Marschall, Reference Marschall2015) and thereby stimulate communication on several levels, allowing the couple to dwell in moments of pleasure and ‘togetherness’ again.

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by Cardiff Metropolitan University's School of Management Ethics Committee, and process consent (Dewing, Reference Dewing2007) was adopted to ensure the co-researchers’ wellbeing and ongoing consent was obtained in light of the potential variation in cognition and mental capacity over the course of the research. The couple were granted anonymity and given the pen names Georgia and David. Since researcher reflexivity and the reduction of power relations is central to sensory ethnography (SE), the co-researchers (the couple) chose the appropriate methods in the specific moments in time and made decisions about how they wanted the research to progress. In fact, over time, Georgia led the direction of each session, just as she had been in charge of organising their holidays in the past.

Methodology

To explore the meaning and significance of recalling shared holiday memories for people living with moderate dementia and their partners, a methodology of SE was adopted (Pink, Reference Pink2015). SE combines methods to assess language and cognition as well as the co-researchers’ senses and emotions during sessions using SOM. This approach draws from the disciplines of anthropology, cultural studies and geography (Rodaway, Reference Rodaway1994; Seremetakis, Reference Seremetakis1994; Classen, Reference Classen1997; Howes and Classen, Reference Howes and Classen2014). Horton and Kraftl identify using autoethnographical methods to provide snapshots of connections between memories, emotions and objects; such methodologies can allow for memories to be ‘Unearthed, recast and (re)made in and through practices with/around material objects during particular lifecourse events’ (Horton and Kraftl, Reference Horton and Kraftl2012: 30) and support embodiment scholarship to frame this study (Csordas, Reference Csordas1990; Merleau-Ponty, cited in Kontos and Martin, Reference Kontos and Martin2013). Whilst most research methods prioritise vision and voice, SE considers other senses (including movement and embodiment) and SE overcomes the barriers experienced in the first phase, without compromising the ability to extrapolate themes where fragments of language and cognition remained intact.

SE as a philosophy adopts the principles of (a) emplacement, (b) interconnected senses and (c) knowing in practice (Pink, Reference Pink2015). The emplacement principle runs parallel to the shifting dementia scholarship of connecting with people who have dementia through being with them in place and time (Howes and Classen, Reference Howes and Classen2014). Rather than objectively conducting research ‘on people’, the researcher becomes embedded within their world. The first stage used autoethnography of the researcher's (JMM) holiday and travel memories to understand emotions and responses when situated in a similar place to the co-researchers, rather than just observing and recording their behaviours. It is proposed that attending to one's own sensory memories can assist in understanding others, by facilitating the extrapolation of knowledge from the collaborative research through shared understanding and empathy. Indeed, the awareness of how the researcher used her senses (from a biographical and cultural perspective) made it possible to become more receptive to how other people use their sensoria. The exploration of similarities between personal experience and that of the co-researchers in the context of recalling holiday memories enabled her to enter the field with an increased sense of knowing and empathy to enable the development of SOM. In so doing, the co-researchers’ beliefs, values and meanings attached to their experiences during the study were explored and reflected upon. As Pink (Reference Pink2015: 98) argues: ‘The sensory ethnographer would not only observe and document other people's sensory categories and behaviours but seek routes through which to develop experience-based empathetic understandings of what others might be experiencing and knowing.’

The second principle of SE demands the assessment of the senses used by participants as a multisensory and interconnected set of sensations (Seremetakis, Reference Seremetakis1994; Ingold, Reference Ingold2000). In Western cultures, the predominant categorisation of senses includes visual (seeing), auditory (hearing), olfactory (smell), gustatory (taste) and tactile (touch), and it is important to note that kinesthetics (movement), perception of time and insight are permitted observations for this research. These extensions embody the emplacement of experience as another insightful dimension of the co-researchers’ views and recollections (Classen, Reference Classen1997; Pink, Reference Pink2008). SOM uses these combined sensory perceptions to allow the co-researchers to return to that holiday moment in time and place. For instance, observations included Georgia putting on her ‘holiday hat’, modelling it and dancing, she relaxed, laughed, fanned herself and exhaled loudly as if hot from the sun, reliving memories of her holidays. This re-enactment transcended time and place, helping her to reconnect with her younger self on holiday. Indeed, Morgan and Pritchard's (Reference Morgan and Pritchard2005) autoethnographic encounters examined the significance that exploring holiday souvenirs have in bringing stories back to life, highlighting how reminiscent research can reveal the importance of objects in helping recall our stories from place to place and past to present time. Whilst we cannot be certain how accurate the recalling is in relation to the actual experiences, this is not necessarily important. As Marschall (Reference Marschall2012: 2217) notes, ‘Such a return to the past can of course not be authentically satisfied but is simulated through invention and reconstruction.’

SE as an effective approach when undertaking research with people living with sensory and perceptual impairments raises the importance of viewing the senses as interdependent and not to privilege one over another (thus marginalising participants who may have multiple perceptual impairments). SE treats the focal relationship as a system of interactions with modern/historic connections and a multi-dimensional and holistic approach to academic understanding. Thus, this study explored the contextual richness of human meaning through examining multisensory, highly complex interrelationships involving body, senses, time and place when identifying the experience of recalling holiday memories. Such multisensorial emplacement offers a superior sense of knowing in practice through analysis conducted iteratively and inductively with reflections by the co-researchers throughout the study.

Methods

The multisensory holiday reminiscence activity involved five visits in 2017 with Georgia and David, both in their mid-eighties. The unfolding research was guided by what they felt were important aspects of their shared experiences. David, who was caring for his spouse Georgia (diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in 2014), was tired and appeared withdrawn on our first meeting. She was aware of her diagnosis and felt guilty for being a ‘burden’ to her husband but despite this, they both communicated their enthusiasm for being involved in the study.

During this first visit, the researcher made it clear that the length of time over which the research would be conducted was uncertain and would depend on the experiences and their emergent conversations. Using SE cannot be time limited in application and is an evolutionary process which gives greater freedom to co-researchers and where meetings reach closure when there is a natural hiatus, in this instance the sharing of the experience with their local Forget Me Not group. Such sessions are sensitive to the free exchange of emotions and developing ideas in a context where there may be difficulties in language and cognitive ability. Using non-threatening interactions (rather than direct questioning) promoted equality and allowed the research to reach saturation of data when the informants exhausted their input. This supports the free-flowing ‘true nature’ research qualities proposed by Holstein and Gubrium (Reference Holstein and Gubrium2004: 141): ‘while the conversations may vary from highly structured, standardized, quantitatively orientated survey interviews, to semi-formal guided conversations, to free-flowing informational exchanges, all interviews are interactional’.

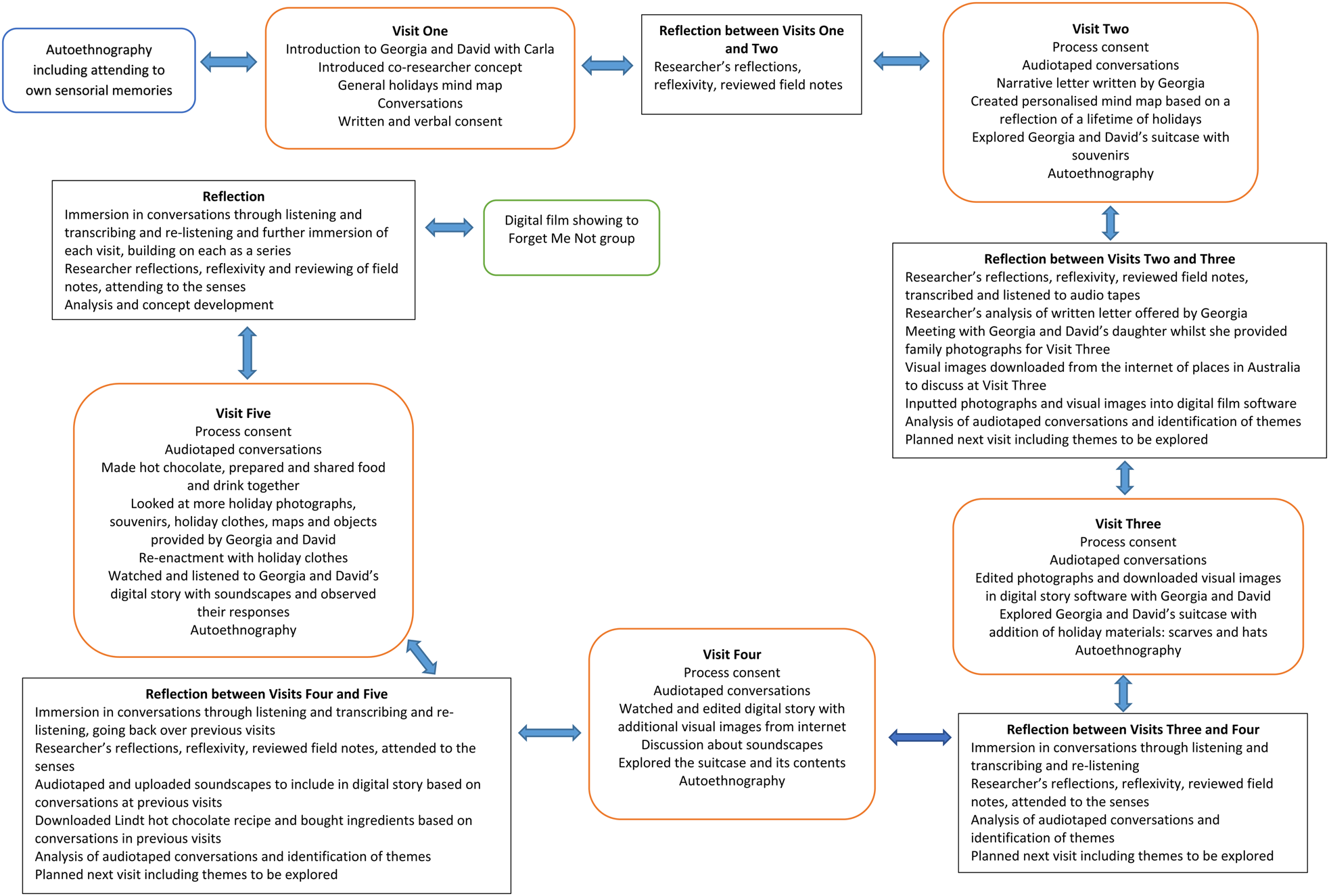

Over the period of the study, David and Georgia filled their old suitcase with holiday memorabilia, clothes and photographs, and we created a digital film with soundscapes and shared food and drink associated with their memories. Following each visit (see Figure 1), field notes were written using Gadamer's (cited in Koch, Reference Koch2006) framework of access, setting, experiences, issues, participant as co-researcher and prejudice, to ensure consistency of observations and personal reflections that included feelings, attitudes, responses and motivations. Such self-awareness can contribute to the exploration (Rolfe, Reference Rolfe2006) and draw from tacit knowledge (Emerson et al., Reference Emerson, Fretz and Shaw2011).

Figure 1. A suitcase of memories – multisensorial methods.

Findings and analysis

SE is an inductive approach to research; the methods and multifaceted analysis are an entwined collation of autoethnographic descriptions, reflections and observations from each visit, using senses as reference points for the memories, and thematic analysis that identifies emergent themes and patterns (Bryman, Reference Bryman2016). The 11 hours of audio recordings were manually coded to understand implicit and explicit meanings that resulted in codes which were tested against the field notes for each visit. The coding process was conducted for each visit and interaction with Georgia and David (who were presented with the themes from each meeting to provide opportunity for them to make further observation, clarification and comment). The result was a common understanding of the strong shared memories and strong associations between the senses and these reminiscences as well as a set of conceptual themes.

During the ethnography, an overreliance on one sense alone was avoided by exploring the combination of sight, sound, touch, smell and taste which brought together the feeling of emplacement when recalling holiday memories for each meeting. Merleau-Ponty (cited in Kontos and Martin, Reference Kontos and Martin2013) promoted this view of an overall sensation of multisensory experiences and this was duly included in the development of SOM and multiple methods to gain a sense of empathy for the co-researchers. During the second visit, Georgia produced a handwritten letter, which she had spontaneously written after the first visit, which described her views about how dementia affected her and how being involved in a study gave her a newfound sense of purpose and meaning. David had filled their suitcase with holiday memorabilia (maps, souvenirs and photographs) and they waxed lyrically, verbally and gesturing (albeit Georgia experienced word-finding difficulties), while the mindmap was redrawn to reflect these responses.

In between visits, a digital film of uploaded personal photographs and added soundscapes was created. Each visit built on the previous, where discussions and re-enactments were conveyed (and gestured when Georgia struggled to finish her sentences or find ‘the right words’) while watching the co-edited digital film and exploring their holiday memorabilia from the suitcase. Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Frohlich, Alm and Vaughan2019) found the use of soundscapes stimulated memory and emotion, and this study confirms the sounds in their film had a profound effect on Georgia's remembering and enhanced the photographs (which sometimes she struggled to focus on). Her responses were striking where she started remembering her emotions (smiling, laughing and gesturing with each sound and image), especially the sound of a kookaburra bird. She could not clearly see the bird photograph until she heard the sound, upon which Georgia laughingly stated:

Oh yes, that sound, every morning that blimmin bird would wake us.

David clearly enjoyed the experience, especially seeing the effect it had on Georgia, where her recall and language were stimulated. They started laughing and joking over many shared experiences; a very different couple than at my first visit where they were separated by the burden of the dementia.

The final visit culminated in a multisensory experience where holiday food and drink were consumed whilst watching their digital film and exploring the contents of the suitcase. Again, positive results were achieved and new insights into shared holiday reminiscences were explored. The evolving digital film archive and accumulated and combined sensory stimulation proved a significant benefit to the process of inquiry and to the outcome of the study (the SOM therapy). It was clear throughout the SOM research that recollections of well-travelled lives, previously forgotten in the midst of living with dementia, which had been dormant in their memories, were now re-emerging. The research process allowed Georgia to express her emotions about dementia (verbally and non-verbally) during the visits which reduced frustrations associated with her condition. Whilst enjoying holiday memories and over the course of the research, her dementia became less of an issue/stress as the joy of her shared holiday memories displaced introspective feelings of isolation. The significance of actively recalling holiday memories was clear, replacing the negative emotions associated with living with dementia with a sense of joy, thereby temporarily relieving the stresses and creating an enjoyable distraction of shared rememberings and togetherness.

The quality of their relationship improved by focusing on a range of holidays/day trips to avoid repetitious accounts and allowed other experiences to emerge and be shared. Such variety supported David and allowed novelty to stimulate a recollection of feelings and experiences:

Georgia was clearly enjoying the reminiscence and the interaction particularly as her day-to-day life was full of reminders of the losses she was experiencing, such as her diminished role in the kitchen because she had burnt the toast, misjudged how hot the boiling water from the kettle was and forgotten a few stages in cooking. When remembering these places, she started to feel as if she was there again on holiday in place and time, which gave her a sense of joy and distracted her from her present-day losses caused by the dementia. It also gave her much to talk about and stimulated her thoughts in a positive way. David seemed to be enjoying the discussion, and whilst they disagreed over some of the facts, I felt that this was a true reflection of their premorbid relationship, where they both held strong opinions and discussed their versions of their memories quite vociferously. The research allowed them to be frank with each other and with me. It seemed as if Georgia had been brought back to life as the visit progressed.

In Georgia's words, the research process re-attuned her to David, which enhanced a sense of connection stimulated by the recalled experiences. She stated:

When you're younger you don't think of time (laughter), or is it because we're getting older and been married for 50 odd years, nearly 60 years? You become attuned to your partner so that stands you in good stead and yes, we don't always agree but the background is there. We're still here, he's not a bad old stick.

Recollections of food and drink (taste) further stimulated their discussions:

David focussed more on the memories of the food and drink on holiday, Georgia joined in, smacking her lips as she recalled some of the meals.

From the collection of narratives, clear themes of ‘holidays as life’, ‘freedom’, ‘view seen, viewpoint heard’ and ‘strengthened self-identity with younger self’ were extracted (by thematic analysis), indicating significant positive benefits for recalling of memories that helped them both re-engage with their individualised self-identities and a new sense of couplehood.

Holidays as life

Holidays and the meanings they hold when re-living them can be very significant life events. Despite Georgia's dementia, she was able to reflect and indicate how the holiday memories were intertwined in their lives and had influenced their overall experience, identity and sense of self, which supports the view of Balfour (Reference Balfour2014: 314) that ‘everyday things’ within people's lives are important. Interestingly, this research concerns tourism memories but there remains a wider context of life memories and latent conversations that exist too:

Well I think you will be able to make a story from all of this (long pause) it's not holidays, though is it? (pause) it's our lives (pause) yes different countries but it's as we've lived them (pause) in different places (pause) it's our life (pause), what you have there is our life (pause) it's our life. (Georgia)

Sitting back in her chair, Georgia would often look back in time and visualise memories (her ‘mind's eye’) without speaking, clearly in a state of contented remembering. This often occurred when combining photographs of the sea with soundscapes of waves. The love of holidaying by the sea was an important factor for both, and when at home, they would visit the beach frequently in their hometown, during their day-to-day lives. They shared happy recollections as they listened to sounds of waves crashing and water lapping at the beach. She made it clear that holidays were significant parts of their life through her body language and that the context of their shared experiences was a meaningful way of accessing these thoughts and feelings.

During a review of a holiday town map, David's fingers walked along the areas on it, where they both remembered the restaurant experiences. His ‘finger walking’ along the map prompted a real-time conversational (verbal and non-verbal) recalled walk, remembering the sights, sounds and smells of the restaurants. Georgia remembered the smell of fish, prompting a repulsive facial expression and pinching of her nose which clearly indicated a stimulated abhorrence to fishy smells. The significance of this experience cannot be underestimated in stimulating the fragmented multi-layered embodied memories of other places and times. Food and drink dominated much of the remembering, particularly for David, recalling Sydney's revolving restaurant with associated sights, tastes and smells, and a café where they frequently enjoyed hot chocolate together.

For the last visit, ingredients and food to share were used to explore their responses (taste and smells). The hot chocolate recipe of the café they frequented was recreated and ingredients included a vanilla bean (which felt like a dried-up banana skin, bendable and springy and strong smelling), cinnamon sticks, long, golden brown and smooth, where David held one up to his nose as if smelling a cigar, and black peppercorns which rolled around in the palm of Georgia's hand. Field note observations showed:

She was frustrated because she had a cold which would not let her smell as well as she'd hoped. I suggested they make it together. When she broke up the dark chocolate, she seemed to enjoy the feel of it in her hands: she threw her head back and inhaled deeply, closing her eyes for a few seconds and saying: ‘It's smelling chocolate: you can smell the chocolate even though I have a nose.’ It is interesting to note how Georgia's sense of smell was stimulated when touching the chocolate. She put the dark chocolate piece by piece into the saucepan, watching it melt rapidly whilst David whisked it up with the spices. The embodied moment of making the hot chocolate together drew out the synaesthetic effects of using the senses of touch and smell together and shutting out sight. As they started to smell the aroma, shared memories of the café came flooding back to them; linking their senses to a sense of place.

The sharing of the food that they had discussed together stimulated memories from different times of their lives, mixing their rural childhoods with holiday experiences. The use of the multisensory reminiscence clearly showed the link between their senses, emotions and remembering as more advantageous than previous single-sensory studies.

Freedom

Oh, I've hopped into Italy! (Georgia)

Tung and Ritchie (Reference Tung and Ritchie2011) found freedom to be a major theme when listening to older people re-living their holiday memories. Georgia and David spoke and gestured about the freedom sensed when holidaying as a couple without dependants:

Warmth, friendliness and ability to move where you want, exploring freedom. (Georgia)

Georgia recalled how she would wander on holiday and was once left behind when on a tour. She did not like to follow everyone else, as she liked to be immersed in the moment, without distractions from others. As she spoke, she gestured with her arms in the air when losing some words, her facial expression lightened and she frequently investigated the distance, as though she was back in the moment of the holiday. She spoke of wearing a red coat when on tours and walks, so that David could find her as she wandered on her own; she laughed and said that it might be a good idea to find that coat again (a direct and humour-based reference to occasionally getting lost nearer home in her current condition).

Georgia articulated the new ability to express herself resulting from the research. Asking her what the best thing about the holidays were, she replied: ‘The freedom to come and go as you please.’ Animatedly speaking about the freedom on holidays, Georgia sat with arms on her lap, occasionally a distant look on her face, but an undoubted relaxed state. An interesting memory of a visit to a large Australian prison showed

The prison (pause) looked in (stammer) I looked in through the bars (pause) it was not in a right place, all this lovely place around here with sailing and there it was somewhere you could definitely be cut off (gesturing with hand) there was no other thing around, of course: they were all sailing and people enjoying life all around that somewhere you could definitely think you were cut off, wherever this was, it's the prison I can see in my mind, the fact that it was isolated, trapped. I remember thinking that I wouldn't want to be stuck there. (Georgia)

Georgia's conversation shifted immediately to hospitals, saying that there was no need to conduct research in hospital. She started to discuss asylums and her negative experience of being given her dementia diagnosis in the building which was the old Victorian asylum. Her flow of thoughts and language became disjointed, her emotions surrounding the memories of the prison were like her memories of the visit to the memory clinic:

Holiday needs, no need to have a hospital environment to make you feel normal (pause) well that you're still capable of living a normal life but maybe a hospital is not. (Georgia)

She continued to refer to old asylums and ‘not being able to come and go as you please’, which is an association, and ‘sense of place’ implied a feeling of fear and negative stigma associated with these institutions. She shivered, raising her shoulders as she said this. Her discussion seemed to have merged her sense of place in the present with a sense of place and freedom and thoughts whilst on holiday and at another time when visiting the memory clinic. The idea of being free to come and go arose many times throughout the visits. David wondered if the meaning Georgia placed on the freedom of holidays was in relation to her lack of freedom now and her fears for the future where it might be further curtailed, as she described a recent experience of forgetting and not recognising where she was when trying to return home from the local shops, a well-trodden journey five minutes away from her home:

I can't remember how to get back (home), that is infuriating therefore, one stays within a perimeter this is a perimeter, you know, your freedom is getting less as you can't go to wider places (pause) it's gone before you realise you've stepped into the next bit. (Georgia)

Throughout every visit, Georgia would compensate for her language difficulties through gesturing, facial expressions and other aspects of non-verbal communication. Despite her expressing how she felt about her sense of freedom being curtailed, she could still see how important SOM was in helping her retain the good memories:

We may be confined nowadays, more confined now, but I don't wander off, but there are times when we used to stroke out (pause) you need the memories when you can't strike out. (Georgia)

View seen; viewpoint heard

Discussion of the view outside their window into their garden became a regular feature during visits, as we noted the changing of the season from winter to spring. Georgia walked over and drew the curtains back, poising her hand as if to show off her garden with a sense of the theatrical, thus, highlighting the importance of a view in helping people connect to the outside world (Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite2018). David came in and spoke about being able to go on day trips more often as the weather was finer, clearly associating me with discussions of trips and holidays. Over the period of the visits, he too became more animated and expressive, clearly enjoying the experience:

I wonder where we will go today!

The experience seemed to elicit a sense of anticipation and hope in them both, in contrast to the couple I met at the beginning, where the dementia dominated their lives. In between my visits, they would go out for their usual trips to a coffee shop, and since the research, they found themselves talking about their holiday memories more. The word view sparked off another direction of conversation as Georgia was reminded about her dementia. She said it was good to get her view heard, which took her back to her loss of role in the home and about not speaking out as much because she would lose track and lose words. She was clearly glad to find her voice again, and this multisensory approach gave her the opportunity to communicate through her body.

Strengthened self-identity with younger self

During the last visit of shared food and drink, film review and physical artefacts from the suitcase, Georgia donned her holiday hat, modelled it and danced over to look at herself in the mirror; she relaxed and laughed, being fully immersed in the experience, reliving her holiday memories. Fanning herself and exhaling loudly as if hot from the sun, her re-enactment transcended time and space, helping her reconnect with her younger self on holiday, who experienced fun and joy. By linking the past to the present through stories of holidays, Georgia's sense of her younger self returned: she embodied a sense of confidence (compared with how she presented herself at earlier visits when her identity was clouded by the dementia). She spoke more confidently, restoring a sense of her own identity as an independent, decision-making woman in contrast to previously, where on earlier visits she believed she was dominated by the dementia. Thus, she showed signs of reconnecting fully with her previous personal identity before the dementia diagnosis, identifying with Sabat and Harre's (Reference Sabat and Harre1992) theories on the complexities of dementia's impact on a sense of the self. Significantly, Georgia exclaimed:

So, the link is from young to us old and doddery (laughter): it's linking the time we're still plodding on over all this time.

Touching and looking at the souvenirs and maps enriched the study by signifying a sense of realness to Georgia and David's holidays, bringing their stories to life once again in the present day. At this point, their stories intertwined between earlier memories and later holidays, moving back and forwards in time depending on the theme of the memory, elicited by the sensory experience: ‘That was the life we lived.’ Interestingly, the stimulation of the senses led them to recalling other memories, possibly where similar emotions were evoked and a sense of identity with their younger selves was relived.

It was clear that the co-researchers moved from a world of negatives and a focus on transactional care for Georgia to a position where:

David seemed to enjoy the experience and, on reflection, it may have also helped distract him from their present-day situation. Both Georgia and David's conversations and sensory experiences were entwined with their individual and shared identities. Initially, they started to recall their holidays chronologically, but once they had both warmed up, they changed to a more fluid recall. The layers of holiday experiences throughout their lifespan were recalled naturally as sensory themes such as tastes and smells of food, sights and sounds, weaved in and out of different times and different places. I felt a tourist in their world, listening and sensing the environment of their home and their holidays whilst enjoying their hospitality. Georgia's own sense of self showed how significant the suitcase of memories was in enabling her to re-identify with herself in relation to her personal identity. (Researcher field notes)

Georgia suggested we share this experience with their local Forget Me Not Group to help others see the benefit of SOM. We visited them a few weeks later, bringing in multisensory aspects of holidaying to the venue, including seashells, buckets and spades, sun cream and ice creams. I spoke with one lady who told me of her extreme sadness at not being able to communicate with her husband anymore; she explained that he did not respond to anything or to her. When we showed the film to the group, I noticed the lady's husband's toe tapping gently to the music that played in their film, I was able to demonstrate to his wife, his small but very significant response which might help her reconnect with him. This dissemination event was an enjoyable multisensory experience for all involved and showed the value in this approach to couples affected by dementia.

Limitations

All reminiscence studies have the potential to stimulate negative or traumatic memories. Here it is recommended that a facilitator of this approach is present, who must be aware of the person's life history to avoid negative triggers where possible. However, Sacks (Reference Sacks2006) argues the importance of providing ways for the person to express themselves and to validate their multi-layered emotions and these emotions need to be observed and clarified. By providing comfort and reassurance, the person's sense of self can still be acknowledged (Craftman et al., Reference Craftman, Swall, Båkman, Grundberg and Hagelin2020) in the home environment. It was clear that Georgia valued being listened to.

The principal limitations of SE and the SOM approach concern replicability of the research by others. The time and effort involved is substantial whilst conducting the sessions and reflecting upon them. The researcher must be sympathetic to energy levels, tiredness and conflicts between co-researchers as they reminisce. When developed further, SOM may be facilitated by a family member, support worker or volunteer, and the skills associated with such a therapy (from facilitation to digital film editing) may need to be standardised in order to optimise the process and its benefits. However, some aspects of SOM may be created solely between the couples living at home together. This research exercise has also focused on historic memories of travel and it is acknowledged that some couples may wish to explore places they have wanted to visit or plan to, thereby focusing on the hope of the present and potentially future expeditions.

Conclusion

The SE approach has challenges in terms of separating methodology and analysis. Whilst pursuing a process there is no doubt that the pluralist methods have significant advantage over traditional ‘single sense’-dominated methodologies for people living with moderate dementia. This study highlights the concept of couplehood and the value of sensory stimulation of shared rememberings as an emancipatory process which enables expression of feelings and being valued, respected and listened to. Encouraging meaningful communication, based on their shared histories, SOM brought their past life to their present. It framed a positive mental attitude to the current moment and fostered new ways of connecting from a situation of negativity and loss towards a feeling of wellbeing and couplehood at the end of the study. SOM stimulated cognition, emotion and movement combined in a way that few previous studies have achieved, thereby bringing new meaning to their relationship in the present (Bielsten et al., Reference Bielsten, Lasrado, Keady, Kullberg and Hellström2018).

David and Georgia both stated their pleasure with the experience and said how it had brought them back together, proving stimulation (beyond speech and language) is a major advantage of SOM that can lessen the frustrations often experienced when unable to express oneself verbally (Craig and Killick, Reference Craig and Killick2011). The SOM study opens new research opportunities based on meaningful and purposeful communication concerning shared experiences. Such emotional memories can remain intact for longer than autobiographical memory (Tappen et al., Reference Tappen, Williams, Fishman and Touhy1999; Kazui et al., Reference Kazui, Mori, Hashimoto, Hirono, Imamura, Tanimukai and Cahill2000), so harnessing the positive emotional experiences of remembering past holidays through using the senses helps enhance shared feelings of wellbeing. Lipinska (Reference Lipinska2009) and Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Coogle and Wegelin2016) recommend psychological support to help people adjust to the changes and losses associated with dementia but stop short of stating how this may be achieved. SOM is an effective way to adopt a multisensory activity for couples, which has replaced sad emotions with greater couplehood and positivity as well as meaningful engagement for those involved. The potential for professionals in care settings to incorporate SOM into life-story work offers great opportunities for more practical application, especially in times of enforced isolation (e.g. during the COVID-19 pandemic). The research is ongoing and has been extended to more couples living with dementia to enhance the efficacy of the approach and to generalise beyond this initial experiment, and a guidance pack to using the toolkit in care settings will be trialled.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all the participant and co-researchers living with dementia and their partners who agreed to share their experiences for the benefit of this research, to JMM's supervisors Dr Diane Sedgley, Professor Nigel Morgan and Professor Annette Pritchard, and to Tom Tremayne for his film-making advice.

Financial support

This work was supported by Cardiff Metropolitan University (Vice Chancellor's Bursary Award) which had no role in the research design, execution, analysis or interpretation of data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was given by Cardiff Metropolitan University's School of Management Ethics Committee (reference 2015S0031).