Mental health experts do not have a proud history when it comes to understanding how often very bad things happen to children. Just three decades ago a prominent psychiatric textbook reported that the prevalence of incest was one per million (Reference Henderson, Freeman, Kaplan and SadockHenderson, 1975).

The reductionistic ‘biogenetic’ paradigm that until recently dominated mental health services and research (Reference BentallBentall, 2003; Reference Read, Mosher and BentallRead et al, 2004a ) did not encourage a focus on the psychosocial causes of mental health problems. Issues such as poverty, isolation, discrimination, dysfunctional families and violence were relegated, in the bio-psychosocial or stress–vulnerability model, to mere triggers or exacerbators of a vulnerability usually presumed to be genetic in origin (Reference ReadRead, 2005). However, the researchFootnote 1 summarised here on the prevalence and effects of childhood abuse is an example of a resurgence of interest in ‘psycho’ and ‘social’ factors. Perhaps we are beginning to remember that the originators of the stress–vulnerability model stated that there is such a thing as ‘acquired vulnerability’ and that this can be ‘due to the influence of trauma, specific diseases, perinatal complications, family experiences, adolescent peer interactions, and other life events that either enhance or inhibit the development of subsequent disorder’ (Reference Zubin and SpringZubin & Spring, 1977: p. 109).

There seems to be a growing awareness of how far the pendulum had swung away from a genuine integration of the biological and the psychosocial. The realisation that brain differences, usually cited as evidence of biological phenomena, can be caused by adverse events–especially during childhood (Reference Read, Perry and MoskowitzRead et al, 2001a )–has assisted this process. There is also a greater understanding of the role of the pharmaceutical industry in promulgating simplistic physiological explanations and highly profitable chemical solutions. Last year the President of the American Psychiatric Association advised that ‘As we address these Big Pharma issues, we must examine the fact that as a profession, we have allowed the bio-psycho-social model to become the bio-bio-bio model’ (Reference SharfsteinSharfstein, 2005).

It is not sufficient, however, that researchers are paying more attention to the psychosocial causes of human distress. Clinicians need to reflect in their practice this long-overdue swing of the pendulum back towards a more central, evidence-based position. We describe here what we have learned about one way of doing this: asking patients about childhood abuse and responding well when the answer is ‘yes’.

The prevalence and effects of child abuse

A review of 46 studies (n = 2604) of female in-patients and out-patients, most of whom had psychoses, revealed that 48% reported having been subjected to sexual abuse and 48% to physical abuse during childhood. The majority (69%) had been subjected to one or the other (or both). The corresponding figures for men (31 studies, n=1536) were: childhood sexual abuse, 28%; childhood physical abuse, 50%; either one or the other (or both), 59% (Reference ReadRead et al, 2005).

Childhood abuse has been shown to have a causal role in many mental health problems, including depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), eating disorders, substance misuse, sexual dysfunction, personality disorders and dissociative disorders (Reference Mullen, Martin and AndersonMullen et al, 1993; Reference Boney-McCoy and FinkelhorBoney-McCoy & Finkelhor, 1996; Reference Kendler, Bulik and SilbergKendler et al, 2000).

Psychiatric patients subjected to sexual or physical abuse during childhood have earlier first admissions, longer and more frequent hospitalisations, spend longer in seclusion, receive more medication, are more likely to self-mutilate, and have higher global symptom severity (Reference Mullen, Martin and AndersonMullen et al, 1993; Reference Lipschitz, Kaplan and SorkennLipschitz et al, 1996; Reference Read, Agar and Barker-ColloRead et al, 2001b ). They are far more likely to try to kill themselves than are psychiatric patients who have not suffered such abuse (Reference Lipschitz, Kaplan and SorkennLipschitz et al, 1996; Reference ReadRead, 1998). One study, of 200 adult out-patients, found that suicidality was better predicted by childhood abuse than by a current diagnosis of depression (Reference Read, Agar and Barker-ColloRead et al, 2001b ). A general population study found that women who had been sexually abused as children were between 8 and 25 times more likely (depending on the severity of the abuse) to have tried to kill themselves than women who had not been abused (Reference Mullen, Martin and AndersonMullen et al, 1993).

There is now also strong evidence that childhood sexual and physical abuse are related to the symptoms of psychosis and schizophrenia, particularly hallucinations and paranoid delusions (Reference Ross, Anderson and ClarkRoss et al, 1994; Reference Read and ArgyleRead & Argyle, 1999; Reference Read, Perry and MoskowitzRead et al, 2001a , Reference Read, Agar and Argyle2003 Reference Read, Goodman, Morrison, Read, Mosher and BentallRead et al, 2004b , Reference Read, Rudegeair, Farrelly, Larkin and Morrison2006a ; Reference Hammersley, Dias and ToddHammersley et al, 2003; Reference Bebbington, Bhugra and BrughaBebbington et al, 2004; Reference Read, Hammersley, Johannessen, Martindale and CullbergRead & Hammersley, 2006). Recent large-scale general population studies controlling for possible mediating variables indicate that the relationship is a causal one, with a dose effect. For example, a prospective study of over 4000 people in The Netherlands found that those who had suffered ‘moderate’ abuse during childhood were 11 times more likely, and those who had suffered ‘severe’ childhood abuse 48 times more likely, to have ‘pathology level psychosis' than people who had not been abused as children (Reference Janssen, Krabbendam and BakJanssen et al, 2004).

Not everyone is convinced that there is enough evidence to conclude that childhood abuse is a risk factor for psychosis and schizophrenia (Reference Spataro, Mullen and BurgessSpataro et al, 2004; Reference Morgan, Fisher and FearonMorgan et al, 2006; Reference Read, van Os and MorrisonRead et al, 2006b ). We are convinced by the research and by what we hear in our clinical work when we ask people with these diagnoses about their lives. This fact, however, is largely irrelevant to the purposes of the current article. Psychiatrists do not have to be convinced of a causal relationship to each and every diagnostic category to understand the importance of asking the people they are trying to help what has happened in their lives.

Public beliefs and expectations

A recent review (Reference Read, Haslam and SayceRead et al, 2006c ) found that the public in 16 countries believe that psychosocial factors such as childhood abuse, loss, poverty and problematic families play a greater role in the causation of mental health problems than do genes, brain dysfunction or chemical imbalance. This is also true for patients and their relatives (Reference Read, Haslam, Read, Mosher and BentallRead & Haslam, 2004).

A study of Londoners (Reference Furnham and BowerFurnham & Bower, 1992) found that the most endorsed causal models for schizophrenia were ‘unusual or traumatic experiences or the failure to negotiate some critical stage of emotional development’ and ‘social, economic and family pressures’. Furthermore, participants ‘agreed that schizophrenic behaviour had some meaning and was neither random nor simply a symptom of an illness’. In a more recent London study, only 5% of people diagnosed with schizophrenia believed the cause of their problems to be a mental illness and only 13% cited other biological causes, whereas 43% cited social causes such as interpersonal problems, stress and childhood events (Reference McCabe and PriebeMcCabe & Priebe, 2004).

This public belief in psychosocial causes has proved resilient to efforts, eagerly supported by the pharmaceutical industry, to persuade the public to adopt a more biological understanding of human distress. We should note, in passing, that the ‘mental illness is an illness like any other’ approach to public education, intended to reduce stigma, actually increases fear, prejudice and desire for distance (Reference Walker and ReadWalker & Read, 2002; Reference Read, Haslam, Read, Mosher and BentallRead & Haslam, 2004; Reference Dietrich, Matschinger and AngermeyerDietrich et al, 2006; Reference Read, Haslam and SayceRead et al, 2006c ).

The important point here, however, is that because the public, i.e. clients/patients, believe that their problems are caused predominantly by bad things that have happened to them, they probably expect to be asked about these by mental health professionals. A rare study of what users of mental health services think about being asked about childhood abuse found that although the majority (64%) had experienced such abuse in some form, 78% had not been asked about this at initial assessment. Those reporting abuse to the researchers were significantly less satisfied with their treatment, and less likely to believe that their diagnosis was an accurate description of their problems, than the non-abused participants (Reference Lothian and ReadLothian & Read, 2002). Furthermore, 69% of the abused participants believed that there was a connection between their having been abused and their mental health problems, but only 17% believed that the mental health staff thought there was a connection. Their comments included:

‘There were so many doctors and registrars and nurses and social workers and psychiatric district nurses in your life asking you about the same thing, mental, mental, mental, but not asking you why’;

‘I think there was an assumption that I had a mental illness and, you know, because I wasn't saying anything about the abuse I'd suffered no one knew’;

‘I just wish they would have said “What happened to you? What happened?” But they didn't’.

Waiting to be told?

Survivors of childhood sexual abuse are usually very reluctant to spontaneously tell anyone about it. A US study found that the average time before disclosure by individuals who had suffered childhood sexual abuse was 9.5 years (Reference Frenken and Van StolkFrenken & Van Stolk, 1990). A New Zealand study of 252 women who had been sexually abused during childhood found that 52% waited at least 10 years to tell someone, and 28% had told nobody (Reference Anderson, Martin and MullenAnderson et al, 1993). In another New Zealand study, of 191 women who had received counselling for childhood sexual abuse, the average time taken to tell anyone about it was 16 years (Reference Read, McGregor and CogganRead et al, 2006d ).

People are no more likely to tell mental health professionals than to tell anyone else. Indeed, there is some evidence that psychiatric patients underreport childhood abuse (Reference Dill, Chu and GrobDill et al, 1991). For example, when researchers conducted a survey of female in-patients after they returned to the community, 85% of those interviewed disclosed childhood sexual abuse, a rate far in excess of the 48% average reported earlier (Reference ReadRead et al, 2005) for female in-patients (when asked in hospital). Many people with extensive contact with mental health services never reveal their victimisation to clinicians (Reference FinkelhorFinkelhor, 1990; Reference ElliottElliott, 1997).

A New Zealand study (Reference Read and FraserRead & Fraser, 1998a ) compared rates of disclosure when psychiatric in-patients were asked about past trauma on admission and when they were not asked on admission (i.e. either were asked later during the hospital stay or spontaneously disclosed the information). The results, which are shown in Table 1, were similar to those obtained in a replication of the study with psychiatric out-patients (Reference Agar, Read and BushAgar et al, 2002).

Table 1 Disclosure of abuse by psychiatric in-patients

| Disclosure of abuse, % | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of abuse | If asked on admission | If not asked on admission |

| Childhood sexual abuse | 47 | 6 |

| Childhood physical abuse | 30 | 0 |

| Adult sexual assault | 12 | 0 |

| Adult physical assault | 35 | 3 |

| At least one of the four types of abuse | 82 | 8 |

Current clinical practice

Asking

The research summarised thus far might suggest that interpersonal violence ought to be a primary focus when mental health professionals assess clients, formulate the causes of their difficulties and make treatment plans. It does not appear that it is, however (Reference Mitchell, Grindel and LaurenzanoMitchell et al, 1996). In-patient studies in the USA and the UK have found that clinicians identify fewer than half of the cases of abuse reported to researchers. The proportion identified by clinicians ranges from 48% to 0% (Reference Jacobson, Koehler and Jones-BrownJacobson et al, 1987; Reference Craine, Henson and ColliverCraine et al, 1988; Reference MillsMills, 1993; Reference Muenzenmaier, Meyer and StrueningMuenzenmaier et al, 1993; Reference Wurr and PartridgeWurr & Partridge, 1996).

A study of 30 ‘heavy users' of acute in-patient and emergency services who disclosed to researchers that they had been sexually or physically abused during childhood found that none had ever been asked about abuse before (Reference Rose, Peabody and StratigeasRose et al, 1991). A survey of New Zealand women who had been sexually abused during childhood and were later treated by mental health services found that 63% had never been asked about childhood sexual abuse by mental health staff (Reference Read, McGregor and CogganRead et al, 2006d ). These studies focus on sexual and physical abuse, but neglect and emotional abuse may be similarly unrecognised by mental health services (Reference Thompson and KaplanThompson & Kaplan, 1999).

Responding

There has been little research on what mental health professionals do after a client discloses childhood abuse. In a self-report survey of British staff, only 5% of nurses, 10% of psychologists and 24% of psychiatrists said that they take no action when a male client discloses childhood sexual abuse (Reference Lab, Feigenbaum and De SilvaLab et al, 2000). However, three studies of recorded behaviour in such situations, in New Zealand (Reference Read and FraserRead & Fraser, 1998b ; Reference Agar and ReadAgar & Read, 2002) and the USA (Reference Eilenberg, Fullilove and GoldmanEilenberg et al, 1996), found very low levels of response in terms of offering information or support, referring for counselling, documenting the abuse in the patients' files, asking about previous disclosure or treatment, including the abuse in summary formulations or treatment plans, and considering reporting to legal or protection authorities.

Barriers to asking and responding

Box 1 summarises some of the reasons for failure to ask about childhood abuse or to respond well when it is reported.

Box 1 Barriers to enquiry and to appropriate response

-

• Other, more immediate needs and concerns

-

• Concerns about offending or distressing clients

-

• Fear of vicarious traumatisation

-

• Fear of inducing ‘false memories’

-

• The client being male

-

• Client being more than 60 years old

-

• Client having a diagnosis indicative of psychosis, particularly when the clinician has strong biogenetic causal beliefs

-

• Clinician being a psychiatrist, especially a psychiatrist with strong biogenetic causal beliefs

-

• Strong biogenetic causal beliefs in general–in both psychiatrists and psychologists

-

• Clinician being male or opposite gender to client

-

• Lack of training in how to ask and how to respond

More important issues and not wanting to upset the patient

In preparation for designing a training workshop in Auckland, psychiatrists and psychologists were surveyed about their reasons for sometimes not asking about past abuse (Reference Young, Read and Barker-ColloYoung et al, 2001). For both professions, the two most frequently endorsed reasons were ‘too many more immediate needs and concerns' and ‘patients may find the issue too disturbing, or it may cause a deterioration in their psychological state’. The first might be a sensible reason for delaying enquiry (e.g. when faced with acute psychosis or suicidal behaviour). The second is a good reason for learning how to ask sensitively and how to respond therapeutically. Of course remembering bad things that have happened can be distressing, especially if handled clumsily by the person asking about them, but there is no evidence that asking causes any serious or permanent damage, and some evidence (Reference Lothian and ReadLothian & Read, 2002) that not being asked can cause distress and anger.

Reliability and fear of inducing false memories

Not many clinicians gave as their reason ‘my enquiring could be suggestive and therefore possibly induce false memories’. Nevertheless, this response was positively correlated, for both professions, with self-reported low probability of asking about abuse (Reference Young, Read and Barker-ColloYoung et al, 2001). Similarly, the higher the percentage of childhood sexual abuse disclosures that a clinician thought were false (mean 4.9%), the lower the probability that the clinician would ask about abuse. This suggests that for some clinicians the frequent allegations in the media that mental health professionals are repeatedly asking about sexual abuse in a way that plants false memories may be inhibiting their capacity to do their job. The irony here is that, as we have seen, the reality is the opposite: staff rarely ask about abuse at all.

Reports of abuse by psychiatric patients, including those diagnosed with psychosis, are reliable (Reference Meyer, Muenzenmaier and CancienneMeyer et al, 1996; Reference Goodman, Thompson and WeinfurtGoodman et al, 1999). Despite the secrecy often surrounding childhood sexual abuse, corroborating evidence–providing various degrees of certainty–has been found in 74% (Reference Herman and SchatzowHerman & Schatzow, 1987) and 82% (Reference Read, Agar and ArgyleRead et al, 2003) of cases reported by psychiatric patients. As already mentioned, psychiatric patients tend to under- rather than over-report abuse. In a New Zealand study involving multiple professions, participants believed that 7.3% of clients' disclosures of childhood sexual abuse were psychotic delusions (Reference Cavanagh, Read and NewCavanagh et al, 2004). A study directly addressing this issue, however, found that people with schizophrenia were no more likely to make false allegations of sexual assaults than the general population (Reference Darves-Bornoz, Lemperiere and DegiovanniDarves-Bornoz et al, 1995).

Who, when and how to ask

Ask everyone

It is essential, because of the high prevalence of abuse across nearly all diagnostic categories, to ask all patients (Box 2). The temptation to ask only individuals with certain symptoms (e.g. of PTSD) reflects a restricted view of the impact of trauma. Given the very low spontaneous disclosure rate documented above, waiting for clients to disclose abuse does not work. Mental health professionals must actively elicit each person's narrative.

Box 2 Principles of asking

-

• Ask all clients/patients

-

• At initial assessment (or if in crisis, as soon as person is settled)

-

• In context of a general psychosocial history

-

• Preface with brief normalising statement

-

• Use specific questions, with clear examples of what you are asking about

Ask at initial assessment

In the New Zealand survey of psychologists and psychiatrists (Reference Young, Read and Barker-ColloYoung et al, 2001), 62% chose ‘Once rapport has been established’ as the most appropriate time to ask, but 47% chose ‘Usually on admission/initial assessment unless the client is too distressed’ (participants could select more than one response). The reason for asking at initial assessment is that if the question is not posed then it tends not to be asked later (Reference Read and FraserRead & Fraser, 1998a ). If clinicians conducting an initial assessment decide to delay the enquiry they should record clearly that a trauma history has not been taken (and why) and take responsibility for following up when the client is less distressed. Clinicians who are tempted to wait for some magic moment when rapport is just right should remember that, for many abused clients, asking may be a crucial act that encourages rapport rather than creates a barrier to it. For some clients, it might even be a prerequisite (Reference Lothian and ReadLothian & Read, 2002).

Context

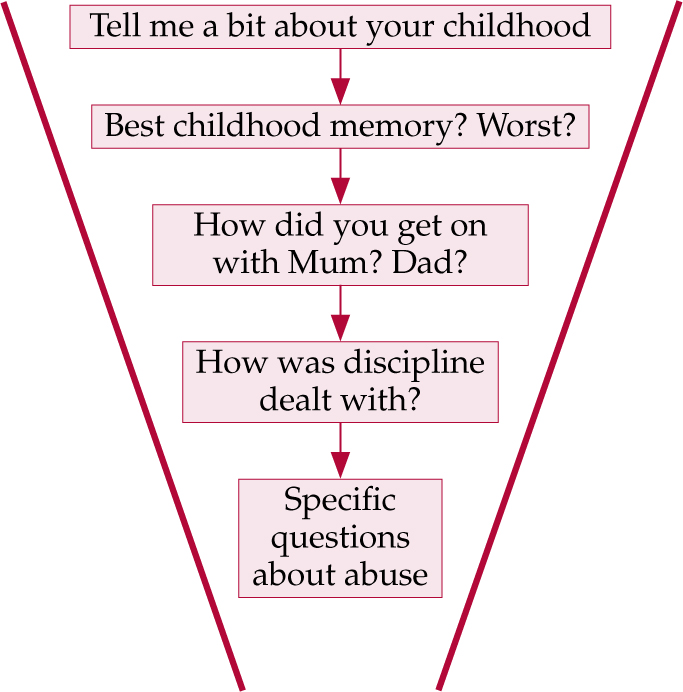

Questions about abuse should not be asked near the outset of an assessment, nor should they come out of the blue with no preface or clear context. The obvious time to ask is when taking a comprehensive psychosocial history, which naturally includes childhood (Box 3). The topic of abuse can be approached using a ‘funnel’ of enquiries (Fig. 1) that narrows down to the specific questions described below. This approach gives the client some warning of what is coming. Asking the individual about their best memory can provide a bit of solid ground to stand on–a reminder for the client (and the clinician) that not everything was bad.

Fig. 1 Funnel from general to specific questions.

Box 3 Possible issues to cover in a psychosocial history

-

• Early childhood, including birth, developmental milestones

-

• School–academic and peer relationships

-

• Family environment during childhood

-

• Adolescence–friends and school, sexuality

-

• Abuse history

-

• Past and current safety issues (harm to/from self/others)

-

• Mental health history (including helpful/unhelpful contact with mental health professionals)

-

• Legal issues

-

• Substance misuse

-

• Medical history (including brain injury)

-

• Employment history (including unpaid)

-

• Interests/hobbies–past and present

-

• Major relationships in adolescence/adulthood

-

• Support history–who client has talked to or does talk to about personal difficulties

-

• Spiritual, religious and other beliefs

-

• Current relationships/family

Preface

It is not essential to preface the questions, beyond what is said to explain the purpose of a psychosocial history, but some clinicians feel more comfortable if they do so. A suitable introduction might be ‘I'm going to ask you about some unpleasant things that happen to some people in childhood. We ask because sometimes it helps throw light on difficulties later in life’, perhaps adding ‘It's fine if you prefer not to answer these questions’. However, it is important not to be too ‘precious’: if people don't want to reveal abuse they probably won't–whether they are given permission or not.

Ask specific/objective/behavioural questions

Asking ‘Were you sexually [or physically] abused’ is not an effective form of enquiry. Many clients will not have used that term in relation to their experiences. If asked directly, some will say that they were not physically abused, but if asked how discipline was dealt with in their family will say something like ‘Oh, the usual–a good belting’.

Reference Dill, Chu and GrobDill et al(1991) found that framing questions in terms of general ‘abuse’ revealed only about half of the abuse identified by questions about specific behaviour. Questions should therefore be about examples of specific events. For example, ‘When you were a child, did an adult ever hurt or punish you in a way that left bruises, cuts or scratches?’ and ‘When you were a child, did anyone ever do something sexual that made you feel uncomfortable?’ Similarly specific questions should be asked covering adulthood, including the present.

Structured questionnaires or interview schedules may be helpful, but if questionnaires are used the clinician should discuss the responses with the patient immediately afterwards. See Reference BriereBriere (1997) for a review of such instruments.

How to respond

For some clinicians, not being sure how to respond may be an additional reason for not asking in the first place (Reference Young, Read and Barker-ColloYoung et al, 2001). Clinicians may feel under pressure to either gather all the details or try to fix the ‘problem’ immediately, or both. The first is unnecessary and undesirable. The second is unrealistic. A guiding principle is to focus more on the relationship with the patient than on the abuse. The important thing is to respond to the fact that a person has just revealed something important. Validation of the person's experience, and of their reactions to disclosure, will communicate both the understanding and the non-judgemental stance of the clinician. Box 4 summarises the important things to remember.

Box 4 Principles of responding to abuse disclosures

-

• Affirm that it was a good thing to tell

-

• Do not try to gather all the details

-

• Ask if the person has told anyone before–and how did that go

-

• Offer support (make sure you know what is available)

-

• Ask whether the client relates the abuse to their current difficulties

-

• Check current safety–from ongoing abuse

-

• Check emotional state at end of session

-

• Offer follow-up/‘check-in’ (see opposite page)

Validation: affirm that telling was a good thing

It is important that the client feels that the staff member has understood the importance of what has been disclosed and that it will, if the client wishes, be returned to later. Clients have a range of responses to disclosing abuse. They might feel anger, shame, self-blame, fear, relief, a lack of connection with their feelings, numb or ambivalent. What is important at this point is that what they have disclosed is met with a positive response.

The clinician should acknowledge that abuse can sometimes be difficult to talk about, but that it is a positive action to have told them about it. It is also important to gauge how the individual is feeling about disclosing, rather than making judgements about what they should be feeling. The kind of responses that might be helpful include: ‘In my experience, people often find that, although it's difficult, it can often be really helpful to talk about it. How is it for you talking about this now?’ People who have been abused often blame themselves. If self-blame does surface it is important to affirm that it is a common reaction and to state that abuse they experienced as a child was not their fault.

Do not try to gather all the details

It is not necessary, or desirable, on first being told by a client that they have been abused to immediately gather all the details (their age when it happened, the identity of the alleged perpetrator, specifics of the acts, etc.). This can all come later, if the person chooses to discuss it. Sometimes, however, clinicians need to ask just enough to ascertain that they are talking about broadly the same thing as the client. If a client does start to give lots of details, it is obviously important to listen, but at some point the clinician might carefully suggest that this material can be returned to later, as there are some other things they would like to ask about now.

Ask whether the person has told anyone before–and how that went

There is a huge difference between a situation in which the patient told an adult at the time of the abuse, was believed and some appropriate action was taken and a situation in which the individual has never disclosed to anyone before. For those who have told someone before it is important to ask what the response was–including whether they received any help such as abuse counselling. If the clinician is the first person in whom the patient has confided it is very important to check the person's emotional state at the end of the session and offer immediate follow-up (see below).

Offer support

It is important to discuss possible treatment and support for the effects of the disclosed abuse. The key word here is ‘offer’. It is best not to imply that the person ‘should’ have treatment of any kind. The clinician should just describe what is available. This implies that they are familiar with the abuse-related services in their own agency and the broader community. Pamphlets summarising this information can be extremely helpful–to both the clinician and the patient. Not everyone will need or want psychotherapy. For some, simply making a connection between their life history and their previously incomprehensible symptoms may have a significant therapeutic effect (Reference Fowler, Birchwood, Fowler and JacksonFowler, 2000).

Ask whether the client relates the abuse to their current difficulties

Regardless of their own views about whether the abuse may be a causal factor in a patient's mental health problems, it is obviously important that clinicians find out the patient's views on this matter. It is the meaning for the patient, not the clinician, that matters. If there is disagreement, this might not be the best time to discuss it.

Check current safety

The clinician should ask whether the patient is still being abused. They should ask also whether the perpetrator might pose a risk to others. For example, if a teacher or priest is named as the perpetrator of childhood abuse, the clinician should ask whether that person is still in contact with children (see below).

Check emotional state at end of session and offer follow-up/‘check-in’

Before ending the session the clinician should ask the person how they feel after having talked about the abuse and, if possible, encourage them to stay calm: ‘Telling someone about what happened can sometimes bring up a lot of feelings. How are you feeling about having told me?’. Clinicians should be able to give patients the name or telephone number of someone they can contact out of hours if they later become upset. They should also help clients to identify their own support systems.

Take good notes

It is important to record accurately what was said. Always use reported speech (‘Anna said that her father often hit her’, not ‘Anna's father often hit her’) or direct quotation (Anna said ‘Dad often hit me’). Files may be used in legal proceedings later on.

Consider reporting to authorities

If there are current safety issues, for example if the patient says that they are still being abused or an alleged abuser still has access to children, decisions about whether to report to the police or child protection agencies should be made in accordance with unit policies on such matters. These policies should include procedures for situations in which confidentiality must be broken (patients should have been informed about these at the beginning of their engagement with the service). Clinicians must be aware of the law as it relates to mandatory reporting in their country. If there is no current safety threat, clients should be offered (but not necessarily immediately) a discussion about taking legal action with someone who fully understands the pros and cons.

Training and policies

Although we hope that the suggestions laid out above will be helpful, training workshops do need to be made available to all mental health professionals. Although the introduction of policies and guidelines is an essential step in establishing a supportive culture for this challenging work, without training little is likely to change (Reference Read, Larkin and MorrisonRead, 2006).

A British study found that only 30% of mental health staff had received training in the assessment and/or treatment of sexual abuse (13% of nurses, 33% of psychiatrists and 46% of psychologists). Of the psychiatrists who had received no such training, 44% nevertheless said that they had received ‘sufficient training’ (Reference Lab, Feigenbaum and De SilvaLab et al, 2000). A US study of psychiatric residents found that only 28% had received training in recognising or treating traumatic events such as domestic violence (Reference Currier, Barthauer and BegierCurrier et al, 1996).

Previous training has been demonstrated to be a good predictor of case identification and initiation of appropriate care (Reference Currier, Barthauer and BegierCurrier et al, 1996; Reference Young, Read and Barker-ColloYoung et al, 2001; Reference Cavanagh, Read and NewCavanagh et al, 2004). In the USA, mental health staff who attended just an hour long ‘trauma orientation’ lecture covering prevalence, effects and sensitive assessment, subsequently identified significantly higher levels of sexual and physical violence, including childhood sexual abuse (37% v. 14%), than those who did not attend the lecture, even though both groups used the same structured interview tool to assess patients (Reference Currier and BriereCurrier & Briere, 2000).

The Auckland training programme

In 2000, the Auckland District Health Board in New Zealand introduced a best-practice document for trauma and sexual abuse. Its stated purpose was ‘to ensure that routine mental health assessments include appropriate questions about sexual abuse/trauma, and that disclosure is sensitively managed’. Its two guiding principles are:

-

1. Assessment of mental health clients must include questions about possible trauma/sexual abuse to ensure that appropriate support and therapy is made available.

-

2. Clinicians should routinely ask about history of trauma, especially occurring during the client's childhood’ (Auckland District Health Board, 2000).

It includes the crucially important statement: ‘Clinical staff are required to undertake a one day skill based training to ensure that questioning techniques are appropriate’ and mandates that the training covers the points summarised in Box 5.

Box 5 Issues covered by New Zealand training programme

-

• Prevalence and effects of abuse

-

• Cultural and consumer perspectives

-

• Learning how to ask about abuse

-

• How to respond to a disclosure of abuse

-

• Note-taking

-

• Legal obligations

-

• Resources available within Auckland District Health Board mental health services

-

• Resources available in the community

-

• Vicarious traumatisation/staff safety

The final point in Box 5, vicarious traumatisation, is important. Listening to accounts of being abused as a child can be very painful for all staff, not just those who have themselves been abused. Staff should use clinical supervision to ‘unload’ some of their feelings about it all, and also seek out other staff with whom they can share feelings.

The Auckland training programme (Reference Young, Read and Barker-ColloYoung et al, 2001; Reference Read, Larkin and MorrisonRead, 2006) has now been running, three or four times a year for 5 years. An early evaluation produced promising results (Reference Cavanagh, Read and NewCavanagh et al, 2004). An article about it in a British nursing journal (Reference Hammersley, Burston and ReadHammersley et al, 2004) resulted in nearly 100 requests for copies of the training manual.

A multidisciplinary research group based at the School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work at the University of Manchester has taken on the challenge of bringing the training previously delivered in New Zealand to a UK audience. This will be in conjunction with the Hearing Voices Network (http://www.hearing-voices.org) and the University of Auckland.

The training will be evaluated much as it has been by the Auckland team (Reference Cavanagh, Read and NewCavanagh et al, 2004), but the evaluation will involve a larger sample and include qualitative methods such as content analysis of action plans and semi-structured interviews. The acceptability of the training, and barriers (personal and organisational) and facilitators to its implementation will also be explored. Given the consistently robust association between childhood abuse and auditory hallucinations it is critical that the Hearing Voices Network is a full partner in the preparation and delivery of the training.

The training day will take the form of an initial summary of the evidence base, followed by service users' personal accounts. Participants will then take part in five specific supervised role-plays, which involve context-setting, direct questioning, response to disclosure, empowerment and ensuring safety. The aim of the training is to equip clinicians with the necessary skills and confidence to ask the right questions and respond appropriately. The workbook that accompanies the training includes contact details for numerous service user groups and support agencies that are able to offer immediate support if necessary. The training will initially be offered to early intervention teams in the northwest of England, but the long-term aim is to make it available throughout the UK. Further details can be obtained by contacting [email protected].

Declaration of interest

J. R. was involved in the design and running of the Auckland training programme, along with Auckland District Health Board clinicians and service users and Auckland Rape Crisis. P. H. is involved in the development of the Manchester-based initiative.

MCQs

-

1 The proportion of childhood abuse cases identified by mental health services is:

-

a 10%

-

b between 0% and 22%

-

c between 0% and 48%

-

d between 22% and 75%

-

e 75%.

-

-

2 Research suggests that childhood abuse is related to:

-

a post-traumatic stress disorder

-

b suicidality

-

c hallucinations and delusions

-

d a and b

-

e a, b and c.

-

-

3 As regards asking about childhood abuse:

-

a all patients should be asked

-

b specific questions, giving examples, should be used

-

c it should not be done at an initial assessment

-

d a and b

-

e a, b and c.

-

-

4 When told that someone was sexually abused as a child:

-

a gather all the details

-

b immediately report it to the police

-

c strongly recommend abuse counselling

-

d ask whether the person has ever told anyone else

-

e a, b, c and d.

-

-

5 Which of the following is a good reason not to ask about abuse?

-

a a diagnosis of psychosis

-

b waiting until a crisis (e.g. acute suicidal feelings) has passed

-

c the person is over 60

-

d the question might plant a false memory

-

e the person's mental health will deteriorate as a result of asking.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F |

| b | F | b | F | b | F | b | F | b | T |

| c | T | c | F | c | F | c | F | c | F |

| d | F | d | F | d | T | d | T | d | F |

| e | F | e | T | e | F | e | F | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.