Introduction

Liver disease is the third most common cause of premature death in the United Kingdom (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Aspinall, Bellis, Camps-Walsh, Cramp, Dhawan, Ferguson, Forton, Foster, Gilmore, Hickman, Hudson, Kelly, Langford, Lombard, Longworth, Martin, Moriarty, Newsome, O’Grady, Pryke, Rutter, Ryder, Sheron and Smith2014). Chronic HCV infection remains a major national health burden [Public Health England (PHE), 2017c] with an estimated 160 000 individuals infected (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Ramsay, Hope, Brant, Hickman, Foster and De Angelis2012). Globally, deaths from viral hepatitis (1.4 million/year) have now surpassed that of HIV (1.3 million/year), malaria (1.2 million/year) and tuberculosis (0.5 million/year) (Global Burden of Disease and WHO/UNAIDS Estimates, 2015). This mandated the first ever WHO Global Health Sector Strategy (GHSS) in May 2016, which aims for elimination of viral hepatitis by 2030 (WHO, 2016). The vision statement of PHE Hepatitis C report is in line with the WHO GHSS (PHE, 2017c).

Injecting drug use is responsible for 90% of all HCV infections in England (PHE, 2017c), with 52% of people who inject drugs (PWID) having a positive HCV serology (PHE, 2017a; 2017b). PHE estimates that about 50% of individuals with HCV may have already been diagnosed (PHE, 2017c); however, only 53% PWID sampled are aware of their HCV antibody positivity status (UAMS, 2017).

Due to the advent of direct acting antivirals (DAAs), there has been a paradigm shift in the management of chronic HCV infection. DAAs have sustained virological response (SVR) rates (ie, cure) in the high 90% despite shorter durations of treatment (8–12 weeks), and are effective orally (Feld et al., Reference Feld, Kowdley, Coakley, Sigal, Nelson, Crawford, Weiland, Aguilar, Xiong, Pilot-Matias, DaSilva-Tillmann, Larsen, Podsadecki and Bernstein2014; Reference Feld, Jacobson, Hezode, Asselah, Ruane, Gruener, Abergel, Mangia, Lai, Chan, Mazzotta, Moreno, Yoshida, Shafran, Towner, Tran, McNally, Osinusi, Svarovskaia, Zhu, Brainard, McHutchison, Agarwal and Zeuzem2015; Kowdley et al., Reference Kowdley, Gordon, Reddy, Rossaro, Bernstein, An, Svarovskaia, Hyland, Pang, Symonds, McHutchison, Muir, Pockros, Pound and Fried2014; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Wagner, Barber and Stover2016). In England, from June 2015 to April 2016, 38% more individuals (7036) accessed treatment (Interim Clinical Commissioning Policy Statement, 2014; Clinical Commissioning Policy Statement, 2015) than mean 2008–2014 levels (PHE, 2017c). This may have contributed to the 8% reduction in deaths from HCV-related end stage liver disease (ESLD) and hepatocellular cancer (HCC) (PHE, 2017c) and 38% reduction in liver transplantation (38%) in 2015 (UK Transplant Registry, 2017). DAA treatment outcomes in PWID are comparable with those in secondary care (Dore et al., Reference Dore, Altice, Litwin, Dalgard, Gane, Shibolet, Luetkemeyer, Nahass, Peng, Conway, Grebely, Howe, Gendrano, Chen, Huang, Dutko, Nickle, Nguyen, Wahl, Barr, Robertson and Platt2016).

Despite the discovery of DAAs, however, we still need a three to fivefold increase in HCV diagnosis and treatment if we are to stem the national HCV burden (Wedemeyer et al., Reference Wedemeyer, Duberg and Buti2014). However, PWID remain a vulnerable cohort with poor engagement with hospital services.

Aims

Our aims are to emphasize the need for community services for PWID with HCV infection and give an overview of the different community models. Secondly, we describe our experiences in setting up a successful nurse led service for screening, stratification and treatment of HCV related liver disease at a substance misuse service (SMS). We highlight the important stages of this process including engaging with stakeholders, obtaining funding and service set up. We also explore the obstacles and challenges faced and summarise our key recommendations. Finally, a brief summary of interim clinical outcomes is presented. Detailed outcome data will not be presented in this manuscript as final data analysis (clinical, qualitative, patient reported and health economic outcomes) will be completed mid-2018 and with the aim to publish in a Hepatology focussed journal.

HCV community service development

Stage 1: Establishing a need

Economic modelling suggests that prioritising HCV treatment in PWID with a ⩽40% HCV seroprevalence and mild to moderate liver disease [in combination with opioid substitution therapy (OST)/needle and syringe programmes] is more cost-effective than treating other patient groups because of the additional benefit of avoiding onwards transmission also known as ‘treatment as prevention’ (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Vickerman, Grebely, Hellard, Hutchinson, Lima, Foster, Dillon, Goldberg, Dore and Hickman2013; Reference Martin, Vickerman, Dore, Grebely, Miners, Cairns, Foster, Hutchinson, Goldberg, Martin, Ramsay and Hickman2016).

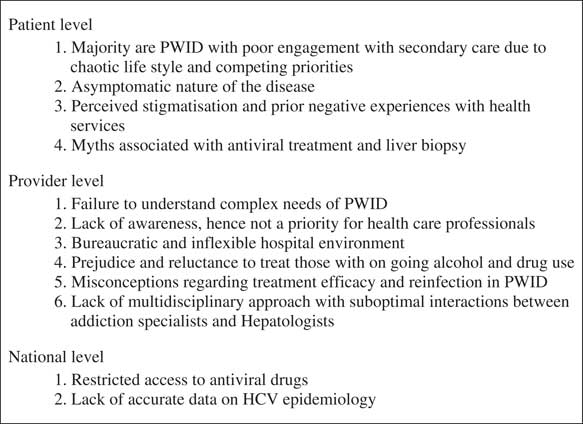

An earlier study from Nottingham, however, showed that overall only 49% of individuals with a positive HCV serology were referred to a specialist, 27% attended and 10% were treated (Irving et al., Reference Irving, Smith, Cater, Pugh, Neal, Coupland, Ryder, Thomson, Pringle, Bicknell and Hippisley-Cox2006). A re-audit about 10 years later showed improvement (80% referred, 70% attended and 38% commenced treatment) though clearly there remained scope for improvement (Howes et al., Reference Howes, Lattimore, Irving and Thomson2016). Barriers to HCV treatment remain at all levels of care (patient, provider and national) (see Figure 1). These include the complex nature of HCV treatment (until recently), inability of health care providers to appreciate the complex needs of vulnerable PWID, perceived stigmatisation and reluctance to treat those actively engaged in alcohol and substance misuse (Irving et al., Reference Irving, Smith, Cater, Pugh, Neal, Coupland, Ryder, Thomson, Pringle, Bicknell and Hippisley-Cox2006; Marufu et al., Reference Marufu, Williams, Hill, Tibble and Verma2012; Dillon et al., Reference Dillon, Lazarus and Razavi2016).

Figure 1 Barriers to care in individuals with hepatitis C virus infection

Locally and as reported by others (Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Genberg, Astemborski, Kavasery, Kirk, Vlahov, Strathdee and Thomas2008; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Kunkel, Axten, Dalton, Gardner, Tippett, Wynne, Wilkinson and Foster2016) we have been cognisant of the poor uptake of HCV services by PWID. In 2011 we appointed a hepatitis nurse at the largest SMS in Brighton to perform blood dry blood spot testing (DBST) for blood borne virus (BBV) screening with onward referral to Hepatology services. Over a six-month period, of those identified with a positive BBV screen (n=73), 14 (19.1%) were known to Hepatology services (two previously treated). Of the 40 individuals suitable for antiviral treatment, only two (5%) engaged with secondary care (42% declined a referral and 37% disengagement with SMS). No individual was eventually treated (Marufu et al., Reference Marufu, Williams, Hill, Tibble and Verma2012). Poor uptake of HCV treatment may be contributing to Brighton and Hove having the highest hospital admission/100 000 population with HCV-related ESLD and HCC (4.8, 95% CI 3.4–6.5), and highest mortality in those aged <75 years from HCV-related ESLD and HCC (1.39, 95% CI 0.70–2.49) in the south east (PHE fingertips).

These data indicates the value of developing innovative community HCV services. Such a novel strategy would represent patient-centred care with earlier diagnosis and treatment, prevention of onwards-viral transmission and potential for reduction in health inequalities. A community-based model with linkage to care is in line with the recently commissioned National Liver Report that advocates screening and treatment for chronic liver disease in the community (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Aspinall, Bellis, Camps-Walsh, Cramp, Dhawan, Ferguson, Forton, Foster, Gilmore, Hickman, Hudson, Kelly, Langford, Lombard, Longworth, Martin, Moriarty, Newsome, O’Grady, Pryke, Rutter, Ryder, Sheron and Smith2014).

NHS targets are to treat 10 000 individuals with HCV infection in 2016, increasing to 15 000/year in 2020 (PHE HCV in England report, 2017). If achieved, statistical modelling predicts that around 2620 people would be living with HCV-related cirrhosis or HCC (a 81% reduction) in England by 2030 (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Martin, Rand, Mandal, Mutimer, Vickerman, Ramsay, De Angilis, Hickman and Harris2016) as mandated by the WHO (2016). This is, however, unlikely to be achieved without engaging PWID.

Overview of HCV community models of care

The model of specialist hepatitis nurses working in SMS/drug and alcohol services has been implemented before, though care has been fragmented, with BBV screening at SMS followed by referral to secondary care (Marufu et al., Reference Marufu, Williams, Hill, Tibble and Verma2012); even if nurse-led treatment has been provided at SMS it is often delivered via out-reach intermittent clinics (Selvapatt et al., Reference Selvapatt, Ward, Harrison, Lombardini, Thursz, McEwan and Brown2016) and does not always include assessment of hepatic fibrosis (Grebely et al., Reference Grebely, Alavi, Micallef, Dunlop, Balcomb, Phung, Weltman, Day, Treloar, Bath, Haber and Dore2016). In other models, homeless individuals attending addiction centres underwent review by a consultant hepatologist and a hepatitis nurse but again only on an intermittent (monthly) basis (Wilkinson et al., Reference Wilkinson, Crawford, Tippet, Jolly, Turton, Sims, Hekker, Dalton, Marley and Foster2009). Directly observed therapy (DOT) with pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RBV) has also been incorporated into opioid substitution clinics (Bonkovsky et al., Reference Bonkovsky, Tice, Yapp, Bodenheimer, Monto, Rossi and Sulkowski2008). Nonetheless, these DOT models are limited to small randomised-controlled trials and involve close collaboration with secondary and tertiary services – not always feasible in a community setting (Bruggmann and Litwin, Reference Bruggmann and Litwin2013).

Group or peer-based treatment has also been trialled, in which an experienced peer co leads the treatment along with a medical provider. This has led to successful treatment outcomes in various settings but relies on pre-treatment engagement (Sylvestre and Clements, Reference Sylvestre and Clements2007). In addition, this model is dependent on excellent group dynamics and effective communication between the peers (Bruggmann and Litwin, Reference Bruggmann and Litwin2013).

In the GP based model, a GP with additional HCV training offers treatment to PWIDs alongside OST (Seidenberg et al., Reference Seidenberg, Rosemann and Senn2013). While this model is simple, provision of addiction and HCV treatment by a single GP is demanding and requires great commitment, effort and training of the primary care provider (Seidenberg et al., Reference Seidenberg, Rosemann and Senn2013). Other primary care strategies employed a specialist nurse working in general practices (Jack et al., Reference Jack, Willott, Manners, Varnam and Thomson2009), but many PWIDs do not engage with their GPs. The Australians, however, have managed to treat >20 000 individuals with HCV infection during March–June 2016 (previously 2000–3000 patients treated per/year). Multiple factors contributed to this phenomenal success including prescribing by GPs (Kirby Institute, 2016). In a recent on-going study in South West England, patients in 46 general practices are being randomised to receive either standard care or a complex intervention comprising educational training, posters and leaflets display, the aim being to raise awareness and encourage opportunistic testing through risk prediction algorithms (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Macleod, Metcalfe, Simon, Horwood, Hollingworth, Marlowe, Gordon, Muir, Coleman, Vickerman, Harrison, Waldron, Irving and Hickman2016).

Other established community HCV programmes such as the American ECHO (The Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) project have also shown great success (Arora et al., 2010). This model links hepatologists with primary care physicians in local communities via telehealth technology. It allows optimal management of HCV patients through ‘knowledge networks’, bringing together expert interdisciplinary specialists from the hospital and multiple community-based primary care practitioners (Arora et al., 2010). Similar outcomes have also been shown in the veteran affairs – ECHO programme (Beste et al., 2016). Other innovative strategies include the French mobile hepatitis team (Remy et al., Reference Remy, Bouchkira, Lamarre and Montabone2016). Table 1 summarises the pros and cons of the different community HCV models.

Table 1 Pros and cons of different community-based hepatitis C virus (HCV) models of care

Stage 2: Obtaining funding and assembling team

Having identified a clear unmet need to link PWID into care by developing a community HCV service model, we then engaged with various stakeholders [SMS, psychiatrists, patient groups (Hepatitis C Trust, British Liver Trust), Brighton and Hove Commissioners, and Pharma].

Our aim was to set up a unique ‘one-stop’ HCV community clinic that provided all components of care (BBV screening, stratification of hepatic fibrosis, nurse-led HCV treatment under hepatologist supervision, hepatitis B vaccination, OST and social and psychiatric input) at one site. In view of the complex needs of PWID our philosophy was that an integrated and multidisciplinary model based at a SMS had the best chance of success. We selected this model rather than one based in primary care due to:

-

∙ Our prior established links with the SMS enabling us to engage PWID in an environment they were comfortable in.

-

∙ A recent meta analysis and systematic qualitative review suggesting that integrating HCV treatment and addiction services enhances HCV treatment adherence amongst PWID (Dimova et al., Reference Dimova, Zeremski, Jacobson, Hagan, Des Jarlais and Talal2012; Rich et al., Reference Rich, Chu, Mao, Zhou, Cai, Ma, Volberding and Tucker2016).

-

∙ A historical reluctance by GPs in England to be involved in antiviral prescription.

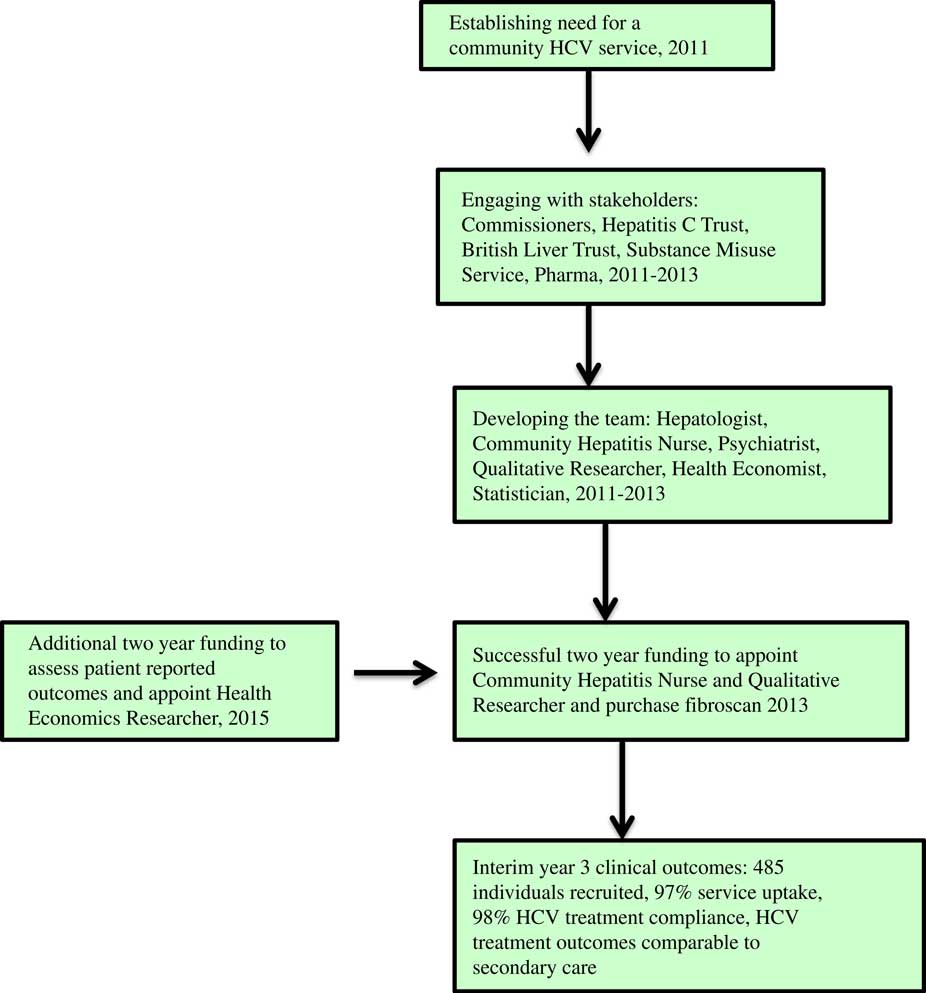

In 2013, we obtained funding for two years (National Gilead Fellowship and Brighton and Hove Commissioners) to set up our community hepatitis C service at the SMS in Brighton (Sussex Partnership Trust). In 2015, additional funding from the same sources extended our work for two years (until December 2017). The funding allowed for appointment of a band 7-community hepatitis nurse and a health economics and qualitative researcher, mobile fibroscan purchase and data collection (clinical, qualitative, patient reported and health economic outcomes). The Fibroscan (Figure 2) is a non-invasive painless liver scan that utilises liver stiffness as a measurement of severity of liver fibrosis (Sandrin et al., Reference Sandrin, Fourquet, Hasquenoph, Yon, Fournier, Mal, Christidis, Ziol, Poulet, Kazemi, Beaugrand and Palau2003). It is now a validated technique (sensitivity and specificity 70~90%) for detection of all stages of liver fibrosis in individuals with most aetiologies of chronic liver disease including HCV (Sandrin et al., Reference Sandrin, Fourquet, Hasquenoph, Yon, Fournier, Mal, Christidis, Ziol, Poulet, Kazemi, Beaugrand and Palau2003; Talwalkar, Reference Talwalkar, Kurtz, Schoenleber, West and Montori2007).

Figure 2 Portable FibroScan® 402 device

Stage 3: Service set up

This involved training of the hepatitis nurse (M.O.S.), identification of a lead psychiatrist at the SMS (H.W.), and detailed discussions with managers at SMS to address logistic issues including clinic space. The service was publicised by the on-going engagement with stakeholders, M.O.S. engaging with SMS staff and use of posters. Figure 3 summarises the stages in setting up the community HCV service.

Figure 3 Stages in developing a community HCV service

Prerequisites for a successful HCV community service

In our view the following were prerequisites for a successful HCV community service:

-

∙ An integrated and multidisciplinary approach with provision of all components of the service at one site, preferably a SMS.

-

∙ An experienced community hepatitis nurse additionally trained in substance misuse and passionate about working with this client group to provide holistic care.

-

∙ Easy access to nurse (mobile phone) and close supervision by a hepatologist.

-

∙ Flexible clinic appointments in contrast to the inflexible, non-personalised and stigmatised environment in secondary care.

-

∙ Community Fibroscan for non-invasive staging of hepatic fibrosis.

-

∙ Presence of onsite psychiatrist.

-

∙ On going alcohol and drug use not a bar to HCV treatment.

-

∙ Personalised strategies for drug delivery (eg, home delivery).

-

∙ Provision of peer advocates (buddies) to support clients throughout their treatment journey.

-

∙ Good engagement between key workers, drug and alcohol team, psychiatrist, peer advocates and hepatitis nurse.

-

∙ Non-judgemental approach.

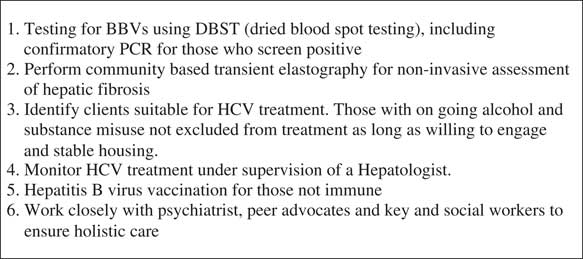

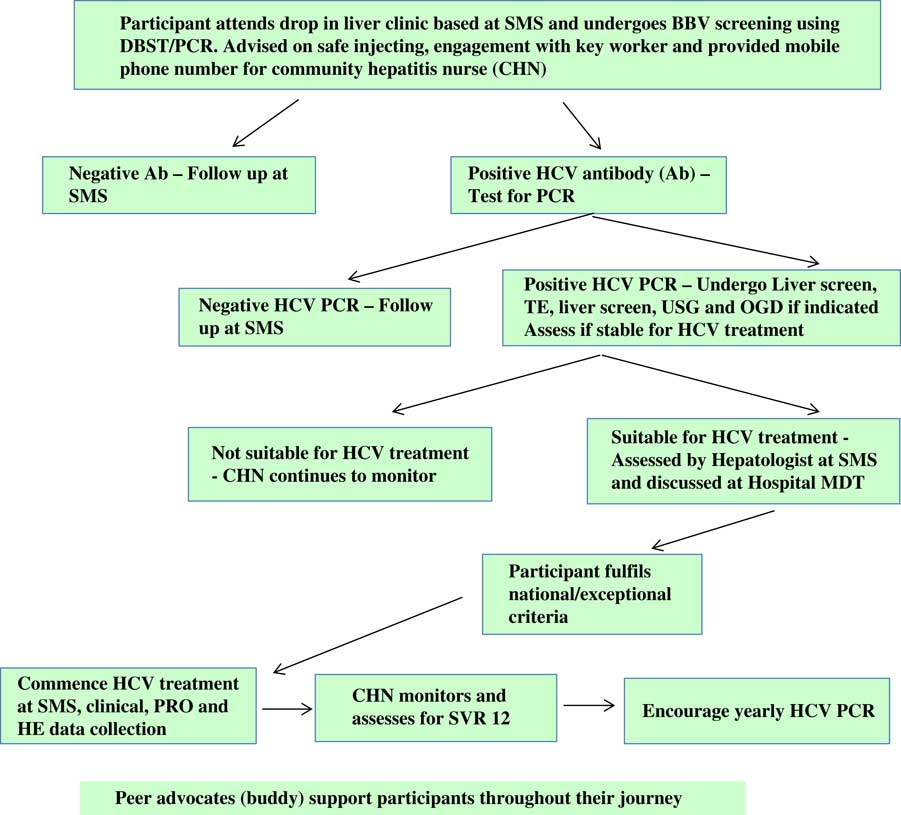

The role of the hepatitis nurse is summarised in Figure 4 and participant pathway in Figure 5.

Figure 4 Role of community hepatitis nurse

Figure 5 Project ITTREAT: participant pathway. SMS=substance misuse service; BBV=blood borne viruses; DBST=direct blood spot testing; PCR=polymerase chain reaction; TE=transient elastography; USG=ultrasound; OGD=oesophagogastroduodenoscopy; PRO=patient reported outcomes; HE=health economics; SVR=sustained virological response.

Delivery logistics and barriers to success

Though the need for a community service was greatly appreciated, set up was associated with a variety of issues that included:

-

∙ Scepticism ‘it ain’t going to work’.

-

∙ Concerns about treating those with on-going drug and alcohol use ‘can’t be trusted with expensive drugs’.

-

∙ Misconceptions about treatment efficacy and reinfection risks in PWID.

-

∙ Logistic issues especially lack of clinical space. A change in providers in 2015 (Surrey and Borders) meant relocating the service to new premises. This heightened the issues of availability of clinical rooms. The SMS have now agreed to install an additional clinical room, that has been been part funded by the research grant.

-

∙ Concerns that interactions between the community hepatitis nurse, psychiatrist and key workers would be incongruent.

-

∙ Remote access to hospital pathology and radiology database – this was resolved with the use of a laptop and remote modem.

-

∙ On-going need to train the staff at the SMS in BBV testing and providing them with the latest HCV treatment updates. This required training of the substance misuse teams volunteers, peer mentors, those running narcotics/alcohol anonymous meetings, homeless hostel workers, rehabilitation units staff and GPs. In the past PWID would have been denied HCV treatment and so it is essential to dispel this antiquated myth amongst the medical and the wider community.

-

∙ Restrictive access to DAA due to prohibitive costs. The Early Access Programme enabled treatment of those with decompensated cirrhosis (Interim Clinical Commissioning Policy Statement, 2014). NHS England then extended treatment to cirrhotics (Clinical Commissioning Policy Statement, 2015) and subsequently to those with advanced fibrosis (LSM>9.5 kPa). There are however exceptional criteria to include those with extra hepatic disease and PWID (as window of opportunity). Treatment can only be dispensed through nationally selected Operator Delivery Networks (ODNs) (n=22), of which we are one. Each patient is discussed at a weekly multidisciplinary meeting. Each genotype has a first choice regimen and all second choice drugs (which in fact maybe more appropriate) need ‘buddy ODN’ approval. There are severe financial penalties for the ODN if guidelines are breached. Each ODN has been provided with a run rate based on the regional prevalence of HCV and again, there are financial penalties for exceeding this. While each ODN can treat a subset of patients (10–20%) under the exceptional criteria, this remains highly scrutinised. It is therefore frustrating that despite effective antivirals and engaged SMS clients who often only have a small window of opportunity; we are still unable to offer treatment to a substantial number of PWID. This is in sharp contrast to countries like Australia where there is unrestricted access to DAA (including for reinfection) and primary care physicians are encouraged to take on prescribing and treatment as already stated (Kirby Institute, 2016).

-

∙ Need for upfront funding for service set up – this has somewhat been negated by establishment of ODN and availability of CQUIN funds.

Evaluating the service

We aimed to evaluate this community-based HCV service through collection of following data:

-

1. Clinical: demographics, drug and alcohol use, uptake of DBST, HBV vaccination and HCV treatment as well as treatment outcomes.

-

2. Qualitative: Conduct of interviews with SMS attendees and two focus groups with staff members.

-

3. Patient reported outcomes using validated questionnaires

-

a. Liver-related quality of life (QOL) – short-form liver disease quality of life (SF-LDQOL) (Gralnek et al., Reference Gralnek, Hays, Kilbourne, Rosen, Keeffe, Artinian, Kim, Lazarovici, Jensen, Busuttil and Martin2000; Kanwal et al., Reference Kanwal, Spiegel, Hays, Durazo, Han, Saab, Bolus, Kim and Gralnek2008).

-

b. Non-disease specific health-related outcomes – SF-12v2, which is a shortened form (12 items) of the SF-36v2 Health Survey (SF-36).

-

4. Assessment of quality adjusted life years using EQ-5D-5L (EQ-5D-5L Survey) and perform a health economics assessment (cost per cure)

Progress

As already stated, detailed outcome data will not be presented in this manuscript. Our Year 3 interim clinical outcomes have been presented at the American Association for Study of Liver Disease meeting (2017) and are summarised below.

-

∙ To date, 485 individuals have been recruited, 80% (n=388) males, mean age 41.0+9.9 years.

-

∙ Prevalence of injecting drug use (IDU) [336 (69%)], alcohol use [416 (86%)] and psychiatric illness [225 (47%)] remains high.

-

∙ Uptake of DBST was 97% (n=472). Prevalence of positive serological markers/PCR were: HBcAb 20% (n=88), HCV antibody 56% (n=262) and HCV PCR 81% (211/262); genotypes 1=92 (44%) and 3=94 (44%).

-

∙ Independent predictors of a positive HCV serology were age, if ever injected, positive HBcAb and if ever had a psychiatric diagnosis (P-value for all ⩽0.003).

-

∙ Of those with a positive HCV PCR (n=211), 169 (80%) underwent transient elastography (TE) [median liver stiffness measurement (LSM) 6.8 kPa (2.7–75], 76 (45%) having significant fibrosis (LSM⩾7.5 kPa, with 42 (25%) having cirrhosis.

-

∙ A total of 66 (31%) individuals were not treatment candidates (chaotic lifestyle), 87/145 (60%) of the remaining with a positive PCR commencing HCV treatment in the community.

-

∙ Characteristics of treated cohort were: age 46±9.2 years; 84% male; 29% and 20% having on-going alcohol and IDU, respectively; 95% undergoing TE [median LSM 8.7 kPa (2.7–75), 39% (34) having cirrhosis including four with decompensation]. Genotypes 1=48%, 3=45%. Treatment received: pegylated interferon+ribavirin 18%, pegylated interferon+DAA 19% and DAA 62%. Of the 79 SVR results available, 69 (87%) have achieved SVR.

-

∙ Compliance with treatment was 98%.

-

∙ No reinfection till date (O’Sullivan et al., Reference O’Sullivan, Williams, Jones and Verma2017).

Project ITTREAT has also been presented at earlier national and international conferences (O’Sullivan et al., Reference O’Sullivan, Williams, Jones and Verma2015; Reference O’Sullivan, Williams, Jones and Verma2016a; Reference O’Sullivan, Williams, Jones and Verma2016b) and was selected by PHE as a showcase for good clinical practice (HCV Action and PHE Hepatitis C Roadshow, 2015). We are also exploring extension of the community hepatitis nurse role to include management of individuals with other forms of chronic liver disease including those with cirrhosis.

There is limited published evidence on community based integrated HCV treatment models in England. Without scientific evidence it will be challenging for local commissioners to develop effective local commissioning business cases. With this conundrum in mind we have drafted a successful business case for a community based integrated model of care. This has ensured the permanency of the community hepatitis nurse once research funding runs out in December 2017.

Based upon the success of Project ITTREAT our team has now established the Vulnerable Adult LIver Disease (VALID) project. This is a similar integrated community liver service based at two homeless hostels and offers non-invasive assessment of hepatic fibrosis (Fibroscan) followed by targeted treatment for chronic liver disease including for BBV (Hashim et al., Reference Hashim, Worthley, Bremner, Macken, Aithal and Verma2017). NHS England have selected the VALID study for inclusion on a website which is a showcase for good practice (Learning Environment – NHS England, 2016).

Conclusions and the future

Linking PWIDs into care is essential if HCV infection is to be eliminated by 2030 as set out in the WHO strategy. These individuals have, however, consistently failed to access traditional models of secondary care. The advent of DAA provides an unprecedented opportunity to address the national HCV burden. Our integrated and multidisciplinary community models of care (Project ITTREAT, VALID Study) have been successful in engaging such individuals with outcomes comparable with secondary care, despite the complex nature of the cohort. Provision of all aspects of the care at one site, a dedicated and highly motivated team and the excellent communication between them and substance misuse staff, other community services, and stakeholders is the key to the success of this service. Our easy to replicate community HCV models have the potential for national adoption as does our business case for such a model.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the staff at the substance misuse service and homeless hostels for their invaluable support and contribution. Finally we are indebted to our patients who despite personal adversity engaged with our services.

Financial Support

This work has been supported by an educational grant from the Brighton and Hove Commissioner and Gilead Sciences (National Gilead Fellowship and Gilead Investigator Sponsored Research Study IN-UK-337-1981). The funders were not involved in the study design and or selection of study outcome measures. Ethical approval was obtained (REC ref no 13/EM/0275).

Conflicts of Interest

S.V.: Research and educational grants/Honorarium from Brighton and Hove Commissioners, Gilead, Dunhill Medical Trust, the National Institute for Health Research and Kent Surrey and Sussex Deanery; Travel grants from B.M.S., Janssen, Abbvie, Gilead; M.O.S.:Travel grants from Gilead; A.H., H.W.: none.