Introduction

When and why do states engage in transnational repression, the targeting of their citizens abroad? What are the implications of such practices for international relations and security? How are practices of transnational repression linked to practices of space-making? In recent years, research on authoritarian transnational repression against citizens living abroad has become an emergent line of inquiry across disciplines of international security, migration studies, sociology, and international relations. Scholars and analysts, however, have only just begun to understand the complicated relationship between authoritarian states and their populations, particularly with regards to specific policies adopted towards their citizens living abroad.Footnote 1 Empirical investigations have demonstrated how authoritarian states adopt strategies of transnational repression to control, extort, or manipulate their populations living abroad.Footnote 2 In her pioneering work, Dana Moss, influenced by the work of Albert, O. Hirschman, defines transnational repression as an act of political control in which ‘the populations cannot fully “exit” from authoritarianism, and that those with domestic opportunities for protest remain constrained in the exercise of their rights, liberties, and “voice”’.Footnote 3 Cases of authoritarian transnational repression, or the targeting of populations living abroad by their home state, are widespread – from China's crackdown on its Uyghur diaspora communities to Iranian's state digital surveillance against exiled dissidents, Turkey's ‘global purge’ of those purportedly linked to the Gulen movement, and the kidnapping and murder of Central Asia's political exiles.

Although the targeting of exiles and opposition actors is not a new practice, the advent of globalisation and rapid development in information communication and technologies are facilitating the quantitative increase and qualitative transformation of these practices.Footnote 4 While current scholarship on transnational repression has advanced our understanding of the tactics and strategies of authoritarian repression abroad, it has not fully studied the implications of such practices on our understanding of space and statecraft.Footnote 5 As authoritarian regimes have increasingly become enmeshed in processes of globalisation, they have used practices of governing regime security, which take place in transnational spaces ‘beyond’ or ‘between states’.Footnote 6 Fiona Adamson observes that the future of global security studies requires a ‘spatial turn’, which demands a greater attention to specific ‘spaces of security’.Footnote 7 In line with Adamson's arguments, Marlies Glasius et al. note that there is ‘an ‘extraterritorial gap’ in the fields political geography and comparative politics, which impedes analysis of extraterritorial state power in general, and extraterritorial authoritarian power in particular.Footnote 8 David Lewis also observes ‘that spatial approaches to the functioning of political regimes have not been sufficiently explored’.Footnote 9

This article contributes to these scholarly debates and extends our understanding of authoritarian governance by highlighting the ways authoritarian states have shaped the development of the spatial dimensions of security practices through cross-border security cooperation, the deployment of digital surveillance technologies, and informal networks composed of security agents and non-state actors. The exercise of state power is embedded in non-national spaces and manifested through spatially organised actors, networks, and technologies. Space in such context is a construct, created through social relations.Footnote 10 Here, we borrow from Saskia Sassen's work on spatio-temporal assemblages to demonstrate the effects of state power through transnational repression.Footnote 11

We thereby conceptualise transnational repression as a series of ‘arrangements of humans, materials, technologies, organisations, techniques, procedures, norms, and events’Footnote 12 that produce new territorial organisations and forms of governance. Such assemblages reproduce, for brief moments, the authoritarian power of the state in extraterritorial spaces. Thinking about assemblages as forms of relational arrangements, highlights a particular set of practices or mode of ordering that brings elements together.Footnote 13 Therefore, our analysis focuses on practices of assemblage – how elements are brought together, sustained, and reconfigured in the exercise of transnational repression.

We adopt a comparative case study design based on ‘the most similar systems design’.Footnote 14 We compare two most similar cases from Tajikistan with different outcomes and study how spatial practices in the field on transnational repression are deployed, how they escalate, and how they affect the political exile community's understanding of the state. Drawing on our empirical observations from the Central Asia Political Exiles Database (CAPE)Footnote 15 and interviews conducted with exiled dissidents from two opposition groups from Tajikistan – the Islamic Revival Party of Tajikistan and Group 24 – the article builds a theoretical framework of the spatial dynamics of power between authoritarian states and their political exiles in the era of globalisation.

The first part of the article examines the authoritarian state as a territorial and extraterritorial actor through the concept of transnational repression. The second inductively derives a framework of transnational repression with three escalating stages through a large-n descriptive data of the CAPE project. Part three outlines our two most similar cases from Tajikistan and our methodology. The subsequent three parts examine the practices in each of these stages in turn: placing an exile ‘on notice’; arrest and detention; and forced return and end game. We conclude by relating our findings to other research on the transnational dimensions of authoritarian rule.

Transnational repression

In an era of globalisation, a ‘nation's people may live anywhere in the world and still not live outside the state’.Footnote 16 Once a migrant has emigrated, their home state does not lose interest in them entirely.Footnote 17 David Fitzgerald has named this process of continual obligation ‘extraterritorial citizenship’ or ‘citizenship in a territorially bounded political community without residence in the community’.Footnote 18 Others have used terms such as ‘the extra-territorial nation’,Footnote 19 ‘external citizenship’,Footnote 20 ‘emigration state’,Footnote 21 and ‘trans-nations’Footnote 22 to describe the state's claims to jurisdiction over citizens living abroad.

Although a number of studies have examined this ‘transnationalisation of state practices’, most of these focus on the ‘positive’ dimensions of this process, such as the way states try to capitalise on remittances sent back by diasporas or the ways in which political parties attempt to secure votes.Footnote 23 Yet, as Nir Cohen argues, this process is not only one way: ‘citizenship loyalty under conditions of extra-territoriality requires subjects to prove their uncompromised commitment through material displays of identification and active participation in events supporting and valorising the homeland.’Footnote 24 But what happens when citizens living abroad do not fulfil this duty and oppose their home government instead? There is now a wealth of scholarship addressing how states target their exiles living abroad, a concept that has come to be known as ‘transnational repression’.Footnote 25 Human rights groups and academics have increasingly observed such practices by a range of states – both those classified as democracies and autocracies – targeting citizens, and foreign nationals, living beyond their borders.Footnote 26 Israel's global assassinations programme, US-led renditions programmes under the war on terror, and the use of a network of detention centres including such as Guantánamo Bay may be considered examples of these kinds of illiberal practices by supposedly liberal states.Footnote 27

However, transnational repression is far more habitually practiced by authoritarian regimes where it is often targeted against non-violent political opponents. Studies have documented such practices in Iran,Footnote 28 Syria,Footnote 29 Turkey,Footnote 30 the Middle East,Footnote 31 and many other states. These governments seek control over not just of their own territories but any spaces, both physical and virtual, where their political opponents and co-ethnic diaspora are found. For authoritarian governments, transnational repression practices form an extension of their domestic pursuit of regime security. In other words, it involves ‘the practice of internal security within the territory of a foreign state’.Footnote 32 By its very nature, it is therefore inherently a spatial practice.

Yet few have explored the specific spatial elements of transnational repression. Marlies Glasius argues that theoretically the exertion of power across borders should be viewed as multi-dimensional; state relations with its population abroad are governed according to a certain set of practices, which involves policies of inclusion or exclusion and where citizens are treated as ‘subjects or outlaws; patriots or traitors; clients and brokers’.Footnote 33 In such framework, regime critics may be treated as subjects to be repressed when they disobey to regime. Applying a ‘spatial tun’ to his research on transnational repression to the case study on Uzbekistan, David Lewis also notes that ‘contemporary authoritarian states have been producing a “state effect” far beyond their own frontiers, by exporting state coercion, and thus producing new understandings of state space through extraterritorial repressive actions’.Footnote 34

The work of these scholars has made important contribution on addressing issues of extraterritoriality, however the current discussions on extraterritoriality have largely focused on perceiving space as a resource to be closely controlled and monitored by the state against an eventual rebellion. And although the authors acknowledge the multidimensional character of socio-spatial relations, they fail to consider the configuration of such relations in a system of governance embedded in ‘global assemblages’ that enables the transcendence of state power. The implication is not that the state is everywhere, but that through these assemblages the state has a distinctive capacity to reconfigure itself across time, space, and diverse political and cultural settings.

From the state as ‘bordered power container’ to the state as assemblages

Max Weber's classic definition of the state emphasises that states must claim a monopoly of legitimate violence within a given territory.Footnote 35 Put succinctly, ‘the control of territory is what makes the state possible’.Footnote 36 Such a view conceptualises the state as a ‘bordered power-container’ incorporating a government that exercises power over a fixed territory and makes collectively binding decisions in the name of the population.Footnote 37 Traditionally conceived, the international system is structured around three central tenets: the notion of equal sovereignty of states, internal competence for domestic jurisdiction, and territorial preservation of existing boundaries. Yet, as Francesco Ragazzi highlights the ‘increasing claims by governments to monopolies of violence, allocation of resources and “national identity” outside of the very border that entitle them to legitimately do so’, pose a fundamental challenge to the Weberian state defined by the monopoly of violence in a delimited territory.Footnote 38

Globalisation has changed the territorial organisation of state and led to a reconfiguration of the scales that govern state power.Footnote 39 From embassies to free trade zones, foreign military bases, ‘black sites’, and international waters, extraterritorial zones have proliferated across the globe. These involve transboundary networks and formations (which can be national, global, or regional) connecting multiple local and national processes and actors. Such forces have produced a deterritorialised system of governance, effectively ‘unbundling’ what were formerly seen as exclusive territories such as the nation state.Footnote 40 This partial ‘disassembling’ of national states has led to the development of new ‘global assemblages’.Footnote 41 An assemblage is a disaggregated structure with both material and ideational dimensions.Footnote 42 Meaning literally ‘to combine elements, to organise or order them into an ensemble or whole’, assemblages draw attention to the array of institutions, agents, practices, knowledges, and relationships that combine in specific sites.Footnote 43

On this basis, we conceptualise transnational repression as operating a series of complex assemblage structures that stretch across national boundaries, but operate in national settings. Within these assemblages, state power is reconfigured but not necessarily weakened.Footnote 44 Assemblages are intertwined with relations of power.Footnote 45 Power is neither centralised nor evenly distributed in an assemblage.Footnote 46 Instead, power exists in a series of uneven relationships. State powers are therefore decentred and polyvalent, rather than hierarchical. More specifically they operate across multiple sites, agencies, and actors that are directly embedded in components of the state but operate beyond the geographical boundaries of the state. In doing so, assemblages blur divisions between structure-agency, social–material, near–far, and local–global producing complex multi-sited domains that embeds within new practices and structures of security governance and power.Footnote 47

We do not use assemblage thinking as a theory, but a way of reframing our inquiry. What does assemblage thinking reveal about the extraterritorial security practices of the state? An assemblage ‘claims a territory’ through ongoing processes of dispersal and realignment, deterritorialisation, and reterritorialisation.Footnote 48 Assemblage thinking helps us to account for the complex spatial practices, range of actors, and levels at which transnational authoritarian governance operates. Second, it allows us to move beyond a conceptualisation of the state as a homogenous actor. It is a valuable tool for identifying how broad asymmetries of power persist through and constrain the emergence of local security conditions without directly determining them. It further enables us to capture ‘new geographies of power that are simultaneously global and national’.Footnote 49 In the following sections we illustrate these claims through a case study from Central Asia.

Studying Central Asian political exiles: Data, cases, and method

This article draws on the Central Asia Political Exiles (CAPE) database, the first database examining transnational repression practices from the countries of Central Asia (Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan). With 278 entries, CAPE covers the period between 1990 and 2018. We have adopted a mixed-methods approach, where our theoretical and empirical framework has been built inductively from descriptive statistics before being validated via qualitative and comparative methods. In the CAPE database, we identify five categories of political exileFootnote 50 that are observable in a Central Asian context:

1. Former regime insiders and their family members;

2. Members of opposition political parties and movements;

3. Banned clerics and alleged religious extremists

4. Independent journalists, academics, and civil society activists.

5. Others: businessmen, employees, or relatives of political exiles.

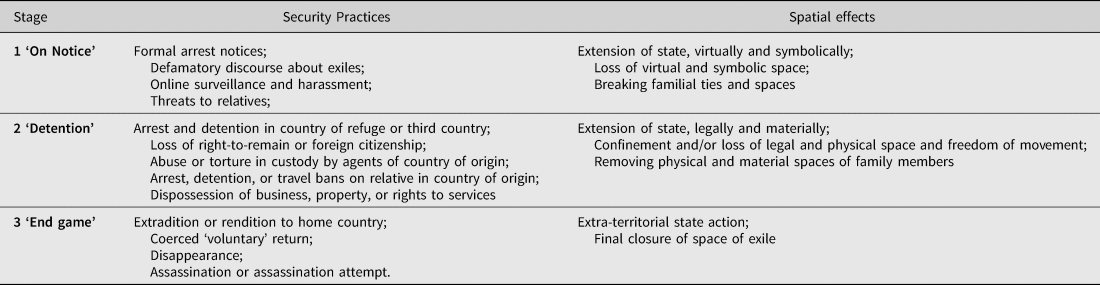

A number of typologies of the ‘repertoires’ of transnational repression exist.Footnote 51 The database adopts a three-stage extraterritorial security model of processes across three stages where individuals are: (1) put on notice; (2) arrested and/or detained; and (3) rendered, disappeared, attacked, and/or assassinated. Each stage contains both formal and informal, territorial and extraterritorial practices. At Stage 1, the spatial closure which takes place is one of freedom of movement and action: arrest notices raise the possibility of detention at ports or in public, confining the person to home and other closed spaces. Threats to family members back home link the exile back to their homeland and subordinate them once again to their government. At Stage 2, arrest and detention overseas constitutes arbitrary confinement of the person – a closure of space that should not be present in a place of refuge. Finally, at Stage 3, a movement back home is achieved or violence is extended extra-territorially, either through direct state action or proxies. The three stages and their attendant practices are therefore inherently spatial – they are about extending the reach of the state transnationally and restricting the spaces in which exiles can operate. A summary of these practices and their spatial effects is found in Table 1.

Table 1. Security practices found in CAPE database and their inferred spatial effects.

Research on repressive tactics on authoritarian states is by nature ethically and practically demanding.Footnote 52 This is true even in the building of a large-n dataset. For ethical reasons related to research subject safety, the dataset is composed of secondary, published sources. This raises questions of selection bias as the media and human rights groups tend to focus on clear-cut human rights cases often involving high-profile activists and opposition figures on the one hand, and the targeting of suspected terrorists (which are excluded from the database) on the other. However, our clear scope of conditions and the relatively high number of cases complied in the database, enable us to show emerging patterns and spatial elements of transnational repression used by the five states of post-Soviet Central Asia to target dissidents abroad. Therefore, the statistical analysis in this article is largely used as an indicative tool that identifies repeated practices without claiming these are fully representative or causal.

Having compiled the dataset, we further unpacked the effects of the practices identified with data collected in semi-structured interviews with 31 political exiles. Studies that trace how security processes affect the lives of those subjected to them are impossible to undertake without the building of relationships of trust over the long term. Our work was made possible by relationship building and a demonstrated ability to help by providing testimonies on behalf of exiles and similar statements to courts as well as parliaments, governments, and international organisations. Interviews were conducted between 2015–17 in the UK, Russia, Germany, Poland, and other EU states, either in person or online. Conducting research in authoritarian settings presents numerous challenges.Footnote 53 Therefore, for ethical reasons and in order to provide maximum protection to our respondents, interviews cited in this article are anonymised. Our 31 interviewees include some people who feature in our database and some who do not, because their cases have not been made public. We used snowball sampling to identify interviewees. This allows us to combine access to the field through the internal validity of a longlist of cases, and the modicum of external validity provided by interviewees whose cases were not part of inductive process of model building. We corroborated interview sources with secondary data retrieved from the CAPE database, media, and advocacy reports, which confirmed and contextualised our primary sources.

We focus on Tajikistan, a country that experienced civil war after the collapse of the Soviet Union followed by a negotiated settlement that envisioned a constitutional democracy based on power-sharing between the two sides.Footnote 54 As part of the peace accords that ended the civil war in 1997, opposition parties were promised 30 per cent of senior government seats, but this quota was never reached. Instead, President Emomali Rahmon, who has ruled the country since 1992, has consolidated power centred on his extended family and its allies. The latest Freedom in the World report 2021, which rates nations according to civil liberties and political rights, ranks Tajikistan among the twenty most oppressive regimes in the world.Footnote 55 The most recent presidential election took place in October 2020, with Emomali Rahmon, re-elected to a fifth term with 92 per cent of the vote. In 2016, amendments to the Constitution made him ‘Leader of the Nation’, allowing him to rule indefinitely.

The article compares the practices towards and effects on members of the Islamic Revival Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) and Group 24, two opposition groups from Tajikistan, a state that has intensified its use of transnational repression in recent years. The fact that country of origin is the same and time period very similar provides a very strong basis for comparison. These two cases are most similar but differ in three important respects: (1) the scale of transnational repression against the two movements, with Group 24 experiencing a far greater number of incidents both absolutely and relative to their size; (2) the relative damage inflicted on the two movements at the end of the observed period of transnational repression with Group 24 far more affected;Footnote 56 (3) the geographic location of the exile movements with a greater proportion of IRPT members making it from the post-Soviet space to the relative safety of the European Union. Here, (3) appears to be an intervening variable from (1) to (2). The relationship between the greater the scale of the transnational repression and its greater effect on the movement is clear. The most similar comparison thereby allows us to be confident that it is key differences in geography and spatial practice that shape these different outcomes.

Other differences are theoretically insignificant for the purpose of this comparison. The temporal difference is minimal with the crackdown on IRPT in exile beginning in 2015 while the repression of Group 24 began in 2013. The IRPT is nominally a religious party that is almost fifty years old, while Group 24 is a secular movement formed only recently.Footnote 57 However, this religious-secular distinction is easily overstated as the IRPT professes what it calls ‘Euro-Islam’ and held seats within the parliament of the country's secular political system from 2000 to 2015. Both are male dominated, with the majority of members being ethnic Tajiks. Both groups contain former regime insiders and it is for that reason that both are considered threats by their government. And yet transnational repression has been far more extensive on Group 24 and had a far more dramatic effect on its capacity. That a high rate of transnational repression would weaken a movement may seem obvious. But this basic relationship, and our structured comparison, allows us to explore the actual spatial practices that bring this about.

CAPE data appear to confirm this relationship. It records 68 political exiles from Tajikistan subject to transnational repression.Footnote 58 Thirteen per cent of exiles persecuted by the Tajik state are affiliated with IRPT. Europe hosts almost half of IRPT members subject to transnational repression.Footnote 59 The IRPT have remained coherent as an exile movement and since September 2018 the IRPT and three other groups – the Forum of Tajik Freethinkers, Reforms and Development in Tajikistan, and the Association of Central Asian Migrants – merged to form one body called the National Alliance of Tajikistan. Our database shows that the IRPT is disproportionately subject to the mildest practices of transnational repression with 50 per cent of the total at Stage 1 attributed to the IRPT. Meanwhile, Group 24 constitutes 49 per cent of Tajik political exiles and about 76 per cent of them are based in Russia while 15 per cent of its members are in Turkey. Our database shows that among exile groups in our sample for Tajikistan, Group 24 has the highest rate of Stage 2 and Stage 3 incidents. About 64 per cent percent of Stage 2 practices with respect to arrests and detention have been attributed to Group 24 against, 3 per cent for the IRPT. Our records show that 39 per cent of Stage 3 practices with respect to extradition, kidnappings, and suspicious deaths – including the assassination of Group 24 founder and leader Umarali Quvvatov in Istanbul in March 2015 – were recorded against Group 24 compared to 18 per cent against IRPT. It is to these spatial practices and assemblages to which we will now turn.

Security practices and spatial effects in Central Asia's exile communities

Among the five countries of Central Asia, the highest number of incidents of transnational repression have been recorded by Uzbekistan and Tajikistan followed by Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan. The ability of Central Asian states to use transnational repression effectively varies according to space, depending on the country and the conditions of exile. Tajikistan has been somewhat exceptional in this regard. The European Union, and Poland in particular, has become a centre for Tajik exiles with 3,230 asylum applications lodged in the EU in 2016, up from 605 in 2014.Footnote 60 However, exile opportunities in the EU are not shared equally across all Tajik groups. The IRPT is largely dispersed in EU/EEA states while Group 24 members are largely located in Russia and Turkey.

Our descriptive statistics show that the most serious incidents of transnational repression are most likely to occur in former Soviet states where most Central Asian exiles are based. Russia is linked to the home state via formal channels and reciprocal security arrangements (formal transnational repression).Footnote 61 In the post-Soviet territories extradition is governed by the 1993 Minsk Convention on Legal Assistance and Legal Relations in Civil, Family and Criminal Matters.Footnote 62 Although the convention guarantees the rights of those detained under national law and lists four technical reasons why a person cannot be extradited, the document makes no mention of the principle of non-refoulement, the norm of not sending refugees back to a country where they are liable to be mistreated. A similar agreement exists between members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, including China.Footnote 63 Both form examples where the extraterritorial process is legal (within the region's own laws and regional agreements) and thereby institutionalised. In cases in these areas, there is a fairly rapid acceleration through the stages to extradition, where in other cases the process can take years or be halted at Stage 1 or 2. Outside the Minsk area, and other territories, such as Turkey, where security services have sometimes cooperated with foreign states to target their political exiles, formal processes may not get past Stage 1, but in exceptional cases may progress rapidly to a rendition or assassination attempt (Stage 3). As will be explored below, transnational repression seems to escalate in cases where the national security services of the country of origin are able to coordinate their extraterritorial pressure on an exile perhaps by private or criminal actors overseas with measures taken against her/his associates by the national security services at home. These spatial security practices mean that effects of transnational repression must not be analysed purely in terms of the physical location of exile, but in the effective extension of repression and closure of space transnationally. As such, territorial and extraterritorial measures are often so blurred as to make these distinctions misleading. Instead, what we see is the emergence of security assemblages often across the three different stages, bits of territory, authority and rights that appear and disappear in extraterritorial spaces.Footnote 64 The remainder of the article explores the spatial effects of these assemblages among the two Tajik exile communities, Group 24, and IRPT.

Stage 1: Symbolic and virtual extensions of the state

Exiles are denoted as being subject to Stage 1 if they or their associates are subject to a threat of arrest, violence, or coercion by the state, either directly or indirectly, formally or informally. Pressure is often placed on exiles through measures against their relatives at home or threats made via cyberspace; the aim is to increase the cost of further political action and to force the exile to cease their activities. Such practices have been identified in the literature as ‘coercion by proxy’. The aim of such strategies is to target (either physically or by other sanctions) an individual within a territorial jurisdiction of a state, for the purpose of repressing a target individual residing outside its territorial borders.Footnote 65 In effect, the state uses domestic repression as means to deter and punish activists who reside abroad. Such tactics have been typically accompanied by the targeting of family members and associates.

Harassment of relatives of the opposition groups has long been a coercive tool of first choice for authoritarian regimes. In targeting family members, the government is reproducing a practice used widely during the Great Purge under Stalin. This derives from the Russian tradition of krugovaia poruka, often translated as ‘joint responsibility’, or more literally ‘circular control’, which attributes joint responsibility to a group for one of its member's individual actions.Footnote 66 Where the exile is more difficult to reach, their relatives are frequently subject to criminal charges, intimidation, surveillance, and other forms of harassment that affect their everyday lives. An activist from Group 24 who lives in political exile in Europe explains:

Since 2014, my relatives, brothers, and friends are subject to harassment from the government authorities. Every three months the Office to Combat Organisational CrimesFootnote 67 comes to our house to question my parents. Once my brother has been severely beaten up by the security services, they were yelling and swearing at him. Another time, a friend of mine, has been detained and beaten by the Tajik authorities. (Interview 1)

In addition to physically repressive tactics, individuals whose relatives or friends remain in Tajikistan are also subject to psychological pressure from state security services. A political exile activist from Group 24 explained that his parents were compelled to speak against his party activities:

After being beaten up by state security services, both my brother and my father were impelled to give a video interview. In this video, they were asking me to be a good son, stop speaking badly about the government, to end my political activities and come back home. This video was later broadcasted on major television and on the Internet. (Interview 2)

As part of state strategies of harassment and leading to subsequent targeting of relatives back home, many activists have had their social media and email accounts hacked, defaced, or dismantled by pro-regime hackers. In other cases, opposition YouTube accounts have been flooded by complaints about their content, forcing administrators to take them down.Footnote 68

This campaign to misrepresent and discredit the opposition operated at the group level as well. Surveillance is not purely top-down; the government has enlisted the support of ‘volunteers’ in its mission to police the web.Footnote 69 Parents, teachers, and religious leaders are expected to monitor the young people of the community for signs that they are opposed to the regime.Footnote 70 Through such activities, citizens reproduce the government's narrative and maintain its relations of power.

The use of such repressive practices reveals the complicity of various agents and intermediaries involved in state-led coercion-by-proxy strategies. The reliance on digital surveillance – such as monitoring online media and social networks, email accounts, and phone communications – suggest that authoritarian states can quickly identify the ties between activists abroad and family members and acquaintances ‘back home’.Footnote 71 Importantly they reveal the importance of relational ties that allow the reconfiguration of state's sovereign power to develop means of exercising power over populations abroad. The use of such practices demonstrates the manner in which state is reconstituted in particular locations, including cyberspace. As noted by Marcus Michaelsen, the use of digital surveillance and targeting of activists in exile ‘is facilitated by the increasing penetration of everyday life by the internet and social media, leading to a convergence of different social roles and activities on online platforms’.Footnote 72

To exercise its state effect, the home state relies further on the discursive construction of spaces of exile and those who inhabit them. This involves framing the homeland as safe, populated by loyal citizens and spaces of exile as threatening, filled with traitors. State media in Tajikistan has defamed the opposition, linking them to incidents of violence in the country, including a 2015 ‘coup’ attempt and a terrorist attack claimed by Islamic State on 29 July 2018. This securitisation of the diaspora continues many of the themes that emerged in the state media while activists were still living in Tajikistan. Rather than being legitimate political actors, the opposition are framed as ‘saboteurs’ who are attempting to cause instability in Tajikistan.Footnote 73 Not only have they sought shelter outside of the country, but they are also actively supported by ‘foreign sympathisers’. In the state media, exiled political activists are portrayed as cowardly individuals beholden to foreign sponsors.Footnote 74 Accounts in the state media frame opponents abroad as cowards who fled their homeland and live in shame. As one journalist stated: ‘The behaviour of these so-called “political refugees”, or a small group of extremists, is unacceptable and dangerous. They put themselves on display as victims to gain better conditions and foreign protection.’Footnote 75

The government has labelled political exiles as ‘extremists’ who are only adopting a peaceful appearance to gain international sympathy. These state discourses constitute an attempt to delegitimise the political opposition in exile, portraying them as a threat to national security and legitimating measures against them. However, it's important to note that not all of these repressive discursive practices remain online or over the phone. At the Organisation of Security and Cooperation Organisation's (OSCE) Human Dimension Implementation Meeting (HDIM), an annual meeting between civil society and governments, a member of the Tajik government delegation punched and kicked members of the IRPT outside of the meeting.

In Stage 1, then, assemblages involve physical tactics such as violence, surveillance, harassment, and psychological harm, but also discursive practices aimed at intimidating and discrediting exiles. These assemblages not only involve a series of tactics but also a myriad of agents including those employed by the state, those compelled to become online trolls and relatives of exiles through which pressure is asserted. They also operate at multiple levels, combining elements of local pressure on relatives with transnational harassment and intimidation of exiles living abroad. Through these border-spanning practices the distance between home and abroad is broken down.Footnote 76 Tajikistan creates the perception by individual or social groups of the presence of the state beyond its borders, what Timothy Mitchell calls the ‘state effect’, even in the absence of formal authority to exercise its power.Footnote 77 As one target of the Tajik security services in Moscow stated, ‘Tajikistan may be 4,000 kilometers away. But I can still feel its hand!’ (Interview 28). As such, the spatial reach of state's power is inseparable from the social relationships that constitute it. It refers to the ability of the state to permeate everyday lifeFootnote 78 and make itself present at ‘at a distance’.Footnote 79

Stage 2: Physical extensions of the state

Stage 2 involves an escalation of Stage 1 measures; governments in the country where the exile is residing, or transiting detain the exile based on formal or informal requests from the home government. Stage 2, then, involves restrictions on movement, in the form of physical detention. By creating an assemblage consisting of other states (foreign governments), international organisations (Interpol, Shanghai Cooperation Organization), and state actors (intelligence, police services), this forms an effort to physically prevent exiles from utilising spaces of exile to exercise resistance to the home state. Where these extraterritorial extensions of state power are not possible, the spaces of relatives within the home country are closed down. Our analysis demonstrates that about 11 per cent of the IRPT members targeted abroad have been subject to detention compared to 64 per cent for Group 24. Such variation indicates that exiles’ host country play an important role in in facilitating transnational repression, about 73 per cent of detention and arrests have been taken place in Russia, where the Tajik security services have strong ties with the Russian security services.Footnote 80

The clearest mechanism through which exiles are detained is by the dissemination of a request for their arrest via the international police cooperation agency Interpol.Footnote 81 Mirzorakhim Kuzov, the senior leader of the IRPT, was detained in Greece in November 2017. Despite the political nature of the criminal proceedings against him, and the fact that he was previously recognised as a refugee in a European country, Interpol was still unable to prevent the diffusion of the Red Notice alert against him due to its lack of sufficient oversight of the data that passes through its system and is diffused to member states. As a report by Fair Trials International has noted, states’ responses to Interpol alerts are not standardised; individual EU member states follow domestic procedures, which varies from country to country. As such, many national administrations manage and respond to alerts that have been previously cancelled by Interpol but have not yet been deleted from their national databases.Footnote 82 Kuzov was later released.

One third of Red Notices within the CAPE database have been issued by Tajikistan.Footnote 83 Theoretically, Interpol remains politically neutral. According to Article 2 of its constitution,Footnote 84 it is committed to work ‘in the spirit of the ‘Universal Declaration of Human Rights’. Article 3 of the Interpol Constitution states that member states are ‘strictly prohibited’ from using the system to pursue criminals facing charges of a ‘political, racial, religious or military character’. However, increasingly authoritarian regimes are using Interpol to pursue, harass, and attempt to return opponents living abroad. Interpol does not issue arrest warrants itself or employ its own agents to conduct arrests, but distributes arrest requests, in the form of Red Notices or more informal diffusions, issued by member states among 194 national law enforcement bodies worldwide. In recent years, the Tajik government has issued Red Notices against 2,528 citizens, most of whom have allegedly been involved in crimes of terrorism.Footnote 85 Comprehensive global figures on Interpol Red Notices are not available. However, as Tajikistan is a relatively small country, these figures suggest it may have become one of the highest per capita (ab)users of the Red Notice system. Red Notices taken out by the Tajik authorities against Group 24 and IRPT have frequently been criticised as politically motivated by international human rights experts.Footnote 86 About 25 per cent of Tajikistan's Red Notices have been issued against IRPT, and 37.5 per cent against Group 24, making them the two most targeted groups of Tajik political exiles.Footnote 87

While Interpol notices have not been used to successful return any political exiles to Tajikistan, it has been used to make their lives more difficult. Those on Interpol wanted lists can face difficulties opening bank accounts, applying for asylum, and travelling internationally. This is compounded by the fact that states are not obliged to publicise Red Notices. One interviewee, a Group 24 member, now living in Poland, is insecure due to this uncertainty:

I think I am on the Interpol list. I went to open a bank account when I arrived in Poland, but was told that I did not pass the security clearance. My lawyer has written to Interpol requesting information about whether I am in their database. It has been three months and I have not heard. I was recently granted asylum. But I do not want to travel beyond Europe without knowing my status. (Interview 20)

Interpol's lack of transparency creates an uncertain situation for many political exiles, who remain in the dark as to their status. Tajik exiles have been detained in countries including Spain, Turkey, Georgia, Poland, and Greece based on Red Notices. The transmission of data through Interpol does give the accusations credibility in other jurisdictions and among the public. Inclusion on an Interpol list lends legitimacy to the idea that opposition activists are criminals and terrorists. Having IRPT leader Muhiddin Kabiri included on Interpol's wanted list in 2016 was widely mentioned in the state media. The state media frequently refers to the inclusion of members of the opposition in Interpol's wanted lists as proof that the groups are ‘international criminal and terrorist organisations’ that threaten stability not only in Tajikistan, but in the country's where they reside.Footnote 88

In addition to Interpol, exiles have been detained and arrested (often detained without trial for months while the await extradition) through other international organisations such as CIS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation to which Tajikistan is a signatory. The participation of Tajikistan in CIS and SCO reflects broader patterns of diplomatic cooperation in which arrests and detentions are facilitated through shared organisational values and mutual security assistance. Footnote 89

Most exiles who have been detained outside of the post-Soviet space of Russia have managed to secure their release on the basis of the principle of non-refoulement, arguing that they would be in danger of torture and ill-treatment should they return. But in the post-Soviet space with its politicised justice system, and where formal and informal ties between national security services are stronger, the extra-territorial reach of the home state is greater. Maksud Ibragimov, the leader of opposition movement ‘Youth of Tajikistan for the Revival of Tajikistan’, and associate of Group 24, was detained in Moscow in October 2014 based on a Tajik arrest request. Ibragimov held Russian citizenship and lived in Moscow for over ten years. Released after a brief interrogation, in November 2014 unidentified assailants stabbed him six times on a Moscow street.Footnote 90 He was arrested in Moscow in January 2015 and taken to the local Prosecutor's Office. He filed a complaint and was released. Shortly after, he was kidnapped by unknown individuals, placed in the baggage hold of a plane and taken to Tajikistan. He was arrested upon his arrival and, according to his lawyer, he was tortured into stating that his return to Tajikistan had been voluntary. Upon his forced return to Tajikistan, he was sentenced to 17 years in prison.

Stage 2 measures involve the emergence of a state assemblage through which the ‘state effect’ is realised through the coordination between home and host state, sometimes mediated through international organisations. The inclusion of the Tajik state in the governance structure of multilateral organisations such as the SCO and Interpol, enables the reorganisation of the state power within a particular spatial framework. Such structures, as well as bilateral and informal ties between intelligence agencies, empower the state and allow reproduction of domestic security discourses and practices to target wanted individuals abroad. In such context, agents and international organisations become implicit accomplices of state power and authoritarian security governance. In this way, the state is not perceived as a single entity or a formal institution, but rather as a dispersed form of power that produces and enacts the state in the eyes of its citizens.

Stage 3: The violent closure of space

Stage 3, involves the elimination of the extraterritorial spaces in which exiles operate, either by killing exiles or by physically removing them from that space and forcibly returning them to the homeland. Individual cases from CAPE demonstrate that Central Asian exiles regularly disappear from Russia and Turkey under mysterious circumstances (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Worst stage experienced according to alleged affiliation.

At least 18 per cent of IRPT members and 33 per cent of Group 24 affiliates in the dataset have been forcibly returned, or rendered, back to Tajikistan since 1991.Footnote 91 More often than not, exiles are victims of extraordinary rendition, which violates the local law and is often conducted with the acceptance or cooperation of local law enforcement. The case of Nizomkhon Jurayev illustrates these dynamics. Until 2007, Nizomkhon Jurayev was director general of the Kimiyo chemical plant and member of the Sughd regional legislature. But in 2007 the authorities accused him of illegally possessing firearms and embezzling $11 million of state funds. Facing these charges, Jurayev fled the country. In August 2010, Jurayev was detained in Russia. The Prosecutor General granted a request from the government of Tajikistan for Jurayev's extradition in February 2011. But the request was never executed as the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), of which Russia is a member, had ruled that his return would place him in danger.Footnote 92 On 29 March 2012, Jurayev was released from pre-trial detention. His wife and lawyer were not informed. He disappeared. Jurayev had no money or passport. A few days later, Jurayev appeared on national television in Tajikistan. Visibly shaken, he claimed that he had returned voluntarily due to guilt and a desire to see his elderly mother. But according to a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights it is ‘beyond reasonable doubt that the applicant had been secretly and unlawfully transferred from Russia to Tajikistan by unknown persons in the wake of his release from detention in Russia on 29 March 2012’.

Along with the practices of forceful returns and extradition, the Tajik government had recently introduced a new tactic, which offers ‘voluntary return’ apparently as an alternative to mask enforced deportation. This was particularly well illustrated with the case of Namunjon Sharipov, a senior leader of the Islamic Revival Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), who was forcefully returned from Turkey to Tajikistan, where he faced terrorism charges for peacefully exercising his freedom of expression. In 2015, Sharipov fled from Tajikistan to Turkey where he opened a Tajik teahouse and worked as a businessman. On 16 February 2018, the Tajik officials with the acquiescence of Turkish authorities, took custody of Sharipov from a detention centre in Istanbul, where he had been held for 11 days. They drove him to the airport and forced him on a plane to Tajikistan. No communication was received from Sharipov until 20 February, when he made a call to Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty's Tajik service, in which he stated that he had ‘returned voluntarily’ to Tajikistan and was ‘freely going about his affairs’.Footnote 93 It's been strongly assumed that Sharipov has been forced to make such a statement under duress. On previous occasions, as seen above in the case Maksud Ibragimov, activists who have been forcibly returned to Tajikistan have been forced to make similar statements to the press under duress.

A number of Tajik opposition members have been attacked while in Russia and Turkey. At least 78 per cent of total carried physical attacks are taking place in Russia.Footnote 94 In January 2012, an acquaintance arranged to meet opposition journalist Dodojon Atuvullo at a Moscow restaurant. When he arrived, an unknown assailant stabbed him multiple times. Although Atuvullo survived, no one was charged for the attack.Footnote 95 Bakhtiyor Sattori worked briefly as spokesman for the Migration Service of the Republic of Tajikistan in Russia until he lost his position in 2012 being told it was due to his ill health. Following being removed from his post, he wrote an open letter to President Rahmon criticising the work of the embassy in Russia.Footnote 96 He proceeded to make further critical remarks on Facebook. In February 2013, he was stabbed 18 times outside of his apartment in Moscow. He had noticed people following him for the month before the assault.Footnote 97

The government's lengthy campaign to silence Group 24 leader Quvvatov ended on an Istanbul street on 5 March 2015.Footnote 98 After dining with a friend, Quvvatov began to feel sick. Looking to get some fresh air he stepped out onto the street. As he left the apartment building, a masked gunman came from behind and shot him in the back of the head. It later turned out that Sulaiman Kayumov, the friend with whom he was dining, had tried to poison him. A Turkish court subsequently sentenced Kayumov to life in prison for murdering Quvvatov, although the government of Tajikistan was not implicated.Footnote 99 Quvvatov's murder had a significant signalling effect to the exile community. A Moscow-based Group 24 supporter stated shortly after the assassination, ‘we are all scared now. Any of us could be next. The government is trying to intimidate us and it is working’ (Interview 22).

Stage 3 involves the violent closure of exile spaces through killing or forcibly returning the exile to the territory of the home state. Such activities usually serve to silence the exile permanently and also have a signalling effect to others in exile about the risks of their political activities. As David Lewis explains, ‘such acts of violence represent the ultimate ability of the state to project coercion beyond its borders, even into spaces viewed as relatively secure. If a monopoly of violence is seen as a significant indicator of stateness, then the employment of violence by the state beyond its borders invokes alternative extraterritorial spatialities of the state.’Footnote 100 Though informal institutional linkages with foreign security services the Tajik state is able to inflict direct violence, abduct, and return activists and dissidents by force. Additionally, organisations such as CIS (the Minsk Convention) and the SCO, create spaces where extradition is facilitated through mutual security assistance and legal agreements.

In the mid-1990s, for many Central Asian political exiles Russia was a safe haven, partly due to existing visa regime facilitations. In response to the emergence of these exile communities, the secret services of Central Asian states began reaching into Russia to pursue individuals viewed as opponents to the regime. Central Asian states developed an extensive surveillance networks over their citizens residing in Russia.Footnote 101 In most cases, Russia's secret services turned a blind eye to Central Asian secret agents’ activities on Russian soil. Until 2001, most of these activities were in contradiction with Russian law, which establishes formal procedures for extradition requests.Footnote 102 However, in the Putin era, law enforcement cooperation facilitated by the Minsk system, formally in place since 1991, has been increasingly used against political opposition figures on a reciprocal basis. Members routinely extradite or informally render wanted persons.

Furthermore, under the system laid in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), founded in 2001 by China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, extradition and redemption became formalised under ‘Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure’ framework. The framework, embedded within the SCO, has facilitated extraditions of anybody suspect of terrorism, separatism, and extremism. The system became the mechanisms of choice for carrying abduction across national territories and outside judicial procedures or constraints imposed by the international courts.Footnote 103 In such circumstances, increasingly Central Asian governments, including Tajikistan, have used their Russian counterparts to facilitate abduction of perceived regime opponents. Yet, as our observations also demonstrate, Russia is not the only hunting ground for the Tajik security services, the incidents in Turkey that involved forced extradition of IRTP member Namunjon Sharipov in 2018 and the murder of Quvvatov, seem to highlight that similar patterns of informal security cooperation are taking place beyond Russia.

The ‘state effect’ emerges within an assemblage of actors linked together by diplomatic ties and informal cooperation agreements that facilitate the targeting of regime's opponents abroad. It is the interaction between agents and organisational structures both at local and global and levels that shape practices of transnational repression. At the core of these practices is what constitutes mutual understanding, reciprocity, and coordination of actions among actors embedded and performing extraterritorial security practices of the Tajik state.

Conclusion: Assemblages of transnational repression

The case of Tajikistan demonstrates how transnational repression reconfigures state power through networks of actors operating across multiple sites, where the distance between the territorial and extraterritorial has been reduced by advances in technology and communication. Despite evident state weaknesses, the government has nonetheless managed to develop a relatively sophisticated system to govern its diaspora. In other words, Tajikistan ‘is in possession of a considerable state effect whilst possessing very weak state institutions according to “universal” neo-Weberian standards’.Footnote 104 The targeting of opponents abroad does not signify a violation of sovereignty so much as a transformation of the Tajik state itself. Rather than being singular and centralised, the Tajik state is also expressed in the practices of a series of assemblages that transcend territorial boundaries. The nature of Tajik transnational repression practices draw attention to the manner in which specific security practices are assembled in particular locations and how the actors’ various forms of symbolic, institutional, and material power can be realised in specific fields.

We see a series of border-spanning assemblages with emergent lines of force that connect disparate component parts. The assemblage that governs Tajik opposition in exile involves activities that transcend the boundaries between global/local and public/private. The assemblages and their attendant practices described above incorporate a number of elements. In some cases, they combined elements of all three stages, resulting in the eventual rendition or murder of the exiles. In other cases, the assemblage first appeared in a later stage. For example, Kuzov was not aware of his being on notice (Stage 1) until he was detained (Stage 2). These assemblages involved a range of actors including state agencies (The Prosecutor General of Tajikistan, State Security of National Committee, Federal Security Bureau), international organisations (European Court of Human Rights, Interpol), and non-state actors (‘patriotic citizens’, Group 24, the Islamic Renaissance Party). These operated at a number of levels, including the transnational (European Court of Human Rights), national (Federal Migration Service of the Russian Federation), and local (regional police) levels.

Geographically, incidents were dispersed across Tajikistan, Russia, Turkey, Germany, and beyond. They involved both formal practices, such as arrest warrants issued by the Prosecutor General in Tajikistan, and informal practices, such as state-backed protests, kidnapping, and torture. The targeting of exiles is based on a specific knowledge that deems them to be a threat in some way. These assemblages are rooted in relations of power and resistance. Those targeted through these assemblages are not passive victims. They exercise agency and have resisted government practices through a range of tactics including voicing concern through human rights organisations, seeking asylum outside of the assemblage's reach and lodging formal complaints with international courts. Assemblage thinking offers the best way to understand the ‘emergence, heterogeneity, the decentred and the ephemeral in nonetheless ordered’ transnational authoritarian governance.Footnote 105

These assemblages of transnational repression involve the production of space in which the state transcends institutional structures and extends state power from the local to regional and from the national to the global.Footnote 106 States spaces as such are not fixed but rather transformed and reconfigured via a various political mechanisms, interventions and spatio-temporal technologies.Footnote 107 Practices of everyday and exceptional repression blur the distinction between home and abroad in assemblages that momentarily ‘claim a territory’ through ongoing spatial processes of deterritorialisation and reterritorialisation.Footnote 108 Whether state repressive tactics are exercised online or offline, they convey the impression that even though the exile activists have left their home country, these individuals are still under the control of the state.Footnote 109 The use of space in this process, as demonstrated in our analysis, is strategic and carefully managed to reach specific political ends.

The emergence and efficacy of these assemblages is determined by the dynamics within the territories across which they operate. The comparative cases show how the IRPT retains significant vulnerability despite its active members being largely located within the relative safety of EU member states. Increasingly the state is able to penetrate democratic liberal spaces and reproduce domestic security mechanisms and state coercive power. While IRPT has been largely subject to targeting in Stage 1 and to some extent in Stage 3, Group 24 has experienced more severe forms of transnational repression with high levels of incidents occurring in Stage 2 and Stage 3. Cooperation between the Tajik state and its authoritarian allies such as Russia, which is the largest host for the Group 24 has facilitated the targeting and persecution of wanted individuals by the Tajik state.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, transnational repression has profound implications for the individuals living in exile. Being put on notice can inhibit attempts to gain asylum and constrain the ability of opponents to exercise voice from exile. Announcements of charges at home are rapidly followed by arrest requests being issued overseas through Interpol or regional organisations. Political actions by exiles abroad are quickly met by measures against relatives and associates in the home country. State security agents and their allies in organised crime act in extraterritorial places with surprising frequency. Via transnational repression, the authoritarian state of Tajikistan signals to individuals in exile that there is no safe haven abroad.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers of EJIS for their constructive comments on earlier versions of the article. The manuscript arguments were developed following conversations with numerous authors working on transnational repression practices, including: Marlies Glasius, Fiona Adamson, Bahar Baser, Ahmet Erdi Öztürk, Dana M. Moss, David Lewis, Marcus Michaelsen, Gerasimos Tsourapas, and Nate Schenkkan. Earlier drafts of the manuscript were presented at the University of Exeter brownbag seminar and in ASN Conference in May 2017, Columbia University – we are grateful participants and colleagues for their insightful comments and helpful suggestions. This article has benefited from funding from the Open Society Foundations, Grant No. OR201734773.

Supplementary material

To view the online supplementary material, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2021.10

Saipira Furstenberg (PhD) is currently affiliated with the University of Exeter as a research associate. She previously taught politics modules at Oxford Brookes University. Her research interests are in post-Soviet region of Central Asia, extra-territorial politics, international dimensions of democracy, and global governance. Her research has been published in Central Asia Survey; Extractive Industries; and Society. In 2020 she contributed to the report published by Freedom House, ‘Out of Sight, Not Out of Reach: Understanding Transnational Repression’.

Edward Lemon (PhD) is a Research Assistant Professor at 2020 The Bush School of Government and Public Service, Texas A&M University. His research focuses on the transnational dimensions of authoritarianism, including transnational repression and authoritarian regional organisations, with a focus on post-Soviet Central Asia, Russia, and China. He has also conducted research on security issues, including violent extremism and political violence. He is editor of Critical Approaches to Security in Central Asia (Routledge, 2018). His research has been published in Democratization; Central Asian Affairs; Caucasus Survey; Journal of Democracy; Foreign Affairs; Central Asian Survey; the Review of Middle Eastern Studies; and The RUSI Journal.

John Heathershaw (PhD) is Professor of International Relations at the University of Exeter. His research addresses conflict and security in authoritarian political environments, especially in post-Soviet Central Asia. It considers how and how effectively conflict is managed in authoritarian states. He is currently the principal investigator of a DFID-funded project ‘Testing and evidencing compliance with beneficial ownership checks’. John is a founding member of the Academic Freedom and Internationalisation Working Group which undertakes research and has drafted a model code of conduct for UK universities. John's most recent publications are Dictators Without Borders: power and money in Central Asia (Yale 2017). His work appeared in Post-Soviet Affairs, Conflict, Security and Development, Third World Quarterly, among others.