… in the rich and sometimes contradictory details of resistance,

the complex workings of social power can be traced. (Abu-Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod1990:42)

Introduction

Over the past decade, rural communities in and beyond Africa have witnessed increased pressures on their land and livelihoods as a result of the global land rush. In a response to perceived scarcity in the wake of the global crises in food, fuel, finance, and climate in 2007/8, a wide range of public and private investors from national governments to agribusiness corporations to hedge funds rushed to acquire land in the global South for commercial agriculture and resource extraction (Hall, Scoones, & Tsikata Reference Hall, Scoones and Tsikata2015; Moyo, Yeros, & Jha Reference Moyo, Yeros and Jha2012; Borras et al. Reference Borras, Hall, Scoones, White and Wolford2011). Just as the drivers and types of land acquisitions have been diverse, so too have been the political reactions across Africa. Some of those affected by these land deals responded with organized and everyday resistance to dispossession, while others expressed cautious and resigned acceptance of investment projects; still others made efforts to negotiate better terms of inclusion into land deals and global value chains (see Martiniello Reference Martiniello2015; Gingembre Reference Gingembre2015; Moreda Reference Moreda2015; Cavanagh & Benjaminsen Reference Cavanagh and Benjaminsen2015; Sulle Reference Sulle2016; Chung Reference Chung2017; Elamin Reference Elamin2018).

In this article, I contribute to the study of contentious agrarian politics in Africa in the context of the global land grab by examining a lawsuit concerning a dispute over a high-profile agricultural land deal in Tanzania. The case was filed at the High Court of Tanzania (Land Division) in Dar es Salaam in August 2012 by three male farmers in Bagamoyo District, Coast Region, against a foreign investor, Bagamoyo District Council, the Commissioner for Lands, and the Attorney General. Representing themselves and (allegedly) 537 other local villagers, the plaintiffs claimed that they were “lawful owners” of approximately 6,000 hectares of the concession land (totalling 20,373.56 hectares) which the government had granted to a Swedish investor for commercial sugarcane production. They argued that they had obtained the land through customary mechanisms of inheritance and bush clearance between 1940 and 2007, prior to the alleged trespass of the defendants. Conveying a sense of urgency and injustice, the national news media reported on the case with headlines such as “Villagers cry over land grabbing” (The Citizen 2013) and “Villagers up in arms for fear of losing land” (The Citizen 2014). By virtue of a High Court injunction, the plaintiffs were able to temporarily halt the implementation of the land deal early in the lawsuit.

Opposition to the land deal gained further momentum in March 2015, when ActionAid International launched its campaign report and online petition, “Stop EcoEnergy’s Land Grab in Bagamoyo” (ActionAid International 2015). The organization criticized the project for failing to obtain free, prior, informed consent from the local communities, and cited the court case as partly resulting from inadequate consultations. The tables were turned, however, when the judge ruled against the plaintiffs eight months later for failing to provide credible evidence to support their claims. Despite their loss, the plaintiffs justified their lawsuit as rightful resistance to land grabbing and expressed their determination to continue with the litigation: “We will appeal. We deserve to be on the land. We are rightful farmers, residents, and citizens. It’s not right that the investor wants to own all of our land.”Footnote 1

In light of the media reports, the global campaign, and the plaintiffs’ narratives, the lawsuit appears at first glance to be an example of formal-legal resistance—a repertoire of contentious politics whereby individuals and groups harness the law, judicial processes, and rights-based discourses to challenge violations of their perceived notions of justice and demand equitable distribution of resources (see Cavanagh & Benjaminsen Reference Cavanagh and Benjaminsen2015; Grajales Reference Grajales2015). Recourse to law, of course, is not new to land politics in Africa. Legal contention was at the heart of indigenous struggles against colonial and postcolonial land annexations, as documented by the well-known Meru and Barabaig Land Cases in Tanzania (Japhet & Seaton Reference Japhet and Seaton1967; Tenga & Kakoti Reference Tenga and Kakoti1993; Lane Reference Lane1994). Early leaders of the African National Congress also turned to the court system to challenge and demand recompense for the mass dispossession of black South Africans from their land (Ngcukaitobi Reference Ngcukaitobi2018).

Yet, the appearance of resistance can sometimes obscure more than it reveals about the asymmetries of power that shape legal battles over land. While being careful to neither deny nor devalue different expressions of subaltern agency, it is necessary to ask: who was included/excluded in the lawsuit in Bagamoyo, through what mechanisms, for what ends, and with what consequences? Asking these questions troubles the very category of “resistance,” or the a priori valorization of resistance, on which so much of agrarian studies and political ecology scholarship rests. As feminist anthropologists have long insisted, critical scholars must refuse the impulse to “sanitize” the multifaceted interests, intentions, and internal politics of subordinated groups (Ortner Reference Ortner1995:179), and instead use resistance as an opportunity to engage in an ethnographically thick “diagnostic of power” (Abu-Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod1990:42). This idea can be usefully extended to the examination of acts that resemble resistance, or acts that appear to be and are justified as resistance, but may in fact be distortions of it. Without attending to these nuances, we risk tethering the meaning of agency to what Saba Mahmood (Reference Mahmood2005:9) has called “a teleology of progressive politics” that celebrates the heroism of the privileged few who have the resources to engage in formal politics, at the expense of marginalized others who are rendered invisible or silenced in dominant narratives of subversion.

Drawing on these feminist insights to examine the court case in Bagamoyo, this article makes two key contributions to the study of land and agrarian politics in Africa. First, to avoid conflating the lawsuit as an innocuous form of resistance, it is characterized here as an expression of lawfare from below. In their examination of the relationship between law and dis/order in postcolonial states, Jean and John Comaroff define lawfare as “the resort to legal instruments, to the violence inherent in the law, to commit acts of political coercion, even erasure” (Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2006:306). This concept initially denoted efforts by the colonial state to conquer and control indigenous populations through the use of legal force, including the invention and manipulation of law to legitimize land expropriation and dispossession (Comaroff Reference Comaroff2001; Tenga Reference Tenga1998; Alden Wily Reference Wily2012; Ranger Reference Ranger1983; Colson Reference Colson, Duignan and Gann1971; Chanock Reference Chanock1985). With the prevalence of “culture of legality” in the postcolonial world, however, the Comaroffs contend that legal instruments can now be appropriated by a wide range of actors, including “the weak, the strong, and everyone in between” (Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2006:30).

Yet, it is seldom the weakest nor the most marginal that predominate in lawfare from below. This is because access to justice is largely uneven; it requires considerable investments of time, money, and political resources, and costs can rise significantly when legal proceedings are delayed and remain mired in court for years (Bowd Reference Bowd2009; Logan Reference Logan2017; Cavanagh & Benjaminsen Reference Cavanagh and Benjaminsen2015; Askew, Maganga, & Odgaard Reference Askew, Maganga and Odgaard2013). Historically, it has also been rare for African courts to yield favorable results for marginalized groups, and few victories have led to transformative changes, especially for women and ethnic minorities (Hughes Reference Hughes2006; Tenga & Kakoti Reference Tenga and Kakoti1993; Lane Reference Lane1994; Gilbert Reference Gilbert2018; Dancer Reference Dancer2017). Given the prohibitive costs, dismal historical record, and the general lack of confidence and trust in the court system, most rural people have little incentive to bring legal charges against governments and investors, even when they feel legitimately wronged or when their livelihoods are under threat.

In the rare occasion where they are able to lodge legal claims, the plaintiffs are likely to be privileged actors, namely male elites in places such as rural Tanzania, where patriarchal forms of political authority prevail. Recent studies further indicate that rural complainants are often likely to be supported by extra-local allies with greater financial resources, visibility, and reach, such as national and transnational social movements, non-governmental organizations, and legal experts (see Grajales Reference Grajales2015; Alonso-Fradejas Reference Alonso-Fradejas2015; IDI 2018; Mwesigwa Reference Mwesigwa2015; Oakland Institute 2018; Gingembre Reference Gingembre2015). To the contrary, the allies of the plaintiffs in the case presented here have remained largely hidden. These were urban elites, including the lawyer, to whom the plaintiffs had allegedly sold land, as well as sugar industry players who arguably had special interests in frustrating the land deal for private gain (Africa Confidential 2017). Ultimately, what was justified as rightful resistance to land grabbing in Bagamoyo was a perverse lawfare from below; it was as much about maintaining power, wealth, and the interests of a privileged minority as about defending the customary land rights of the many rural poor.

The second key contribution of this article is that it uses an intersectional feminist lens to analyze the hidden operations of power and the politics of exclusion that undergird the exercise of lawfare. As a concept and analytical sensibility, intersectionality emphasizes the multiple and simultaneous ways in which gender is co-constituted with, and reinforced through, other structures of power and identity (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Cho, Crenshaw, & McCall Reference Cho, Crenshaw and McCall2013; Collins & Bilge Reference Collins and Bilge2016). The specific instances and intensities with which gender articulates with other forms of difference and inequality are historically and geographically contingent. Here, the case of lawfare in postcolonial Tanzania acts as a window onto the interlocking dynamics of gender, class, generation, and social status (or gradations of status as expressed through marital, residential, and political status) that shape uneven access to and control over resources. Specifically, I examine how the plaintiffs drew on their multiple and intersecting positions of privilege—as men, elders, husbands, long-term residents, large landholders, village leaders, and rural party elites—to appropriate, erase, and transgress the land rights of diverse other legitimate resource users, including, most immediately, their wives. The ramifications of their lost case were, thus, far-reaching. It led to a heightened sense of uncertainty over the rights and status of local people, irrespective of their involvement in the court case. It exposed existing power asymmetries between the local people, the state, and foreign investors, and reinforced inequalities within the “local” itself, between husbands and wives, older and younger generations, longtime residents and immigrants, large and small landholders, and elites and ordinary people.

Examining lawfare and land politics through an intersectional feminist lens remains highly pertinent in Tanzania and rural Africa, where multiple gendered inequalities have been central to struggles over land and resources. Feminist scholars have shown how daughters, sisters, wives, widows, divorcées, and ethnic minority women continue to face disadvantages in land access as a result of colonially-inflected institutions of customary law, while patriarchal village authorities and state courts remain ambivalent about administering women’s land claims within a context of legal pluralism (see Tsikata Reference Tsikata2003; Dancer Reference Dancer2017; Askew & Odgaard Reference Askew and Odgaard2019; Yngstrom Reference Yngstrom2002; Whitehead & Tsikata Reference Whitehead and Tsikata2003; Mbilinyi Reference Mbilinyi2017; Gray & Kevane Reference Gray and Kevane1999). Even in cases where women are able to initiate land disputes and win legal battles, their claims are often not likely to be taken seriously, or the women are likely to be stigmatized as “wicked” women or “bad” wives for transgressing the boundaries of acceptable gender norms (Hodgson Reference Hodgson1996; Verma Reference Verma2014). An engagement with intersectionality allows this study to build on these works, while highlighting more explicitly the relationship between privilege and marginalization. This enables the analysis to move beyond the exclusive focus on women, exposing the tangled webs of power in which they are enmeshed. Notwithstanding its merits, there are certain methodological challenges to intersectional analysis, including trade-offs in narrative coherence by virtue of decentering gender as the primary object of analysis (McCall Reference McCall2005; Nightingale Reference Nightingale2011). Nonetheless, embracing complexity over analytical convenience is necessary to arrive at a better understanding of the lived realities of rural land politics in Africa and to advance scholarship that is oriented toward social justice.

The arguments I have just outlined are informed by eighteen months of ethnographic research conducted between 2013 and 2016, as part of a broader study on the intersectional politics of the new enclosures in Tanzania. For this article, I draw on and triangulate from multiple data sources, including ethnographic observations, in-depth interviews, oral histories, and court documents. As an inherently interpretive practice, the ethnography here must be understood as partial (Haraway Reference Haraway1988; Denzin Reference Denzin1997). Rather than trying to ascertain the “true” motives of the plaintiffs and make causal claims about what “really happened,” I take interest in pulling together-apart conflicting accounts, silenced narratives, and “mundane reasonings” (Pollner Reference Pollner1974) to tell a broader story about power and inequality in rural Tanzania.

I begin with a brief overview of the large-scale land deal that triggered the lawsuit. I then draw on court documents and interviews to describe in detail the claims made by the plaintiffs and the grounds on which the judge dismissed their case. Next, I contrast witness testimonies with ethnographic observations, oral histories, and interviews to elaborate on who the plaintiffs are, and the exclusionary practices they relied on for their lawfare. In the final section, I discuss the aftermath and ramifications of the lawfare on local politics and community relations. The conclusion offers a reflection on how a seemingly legitimate legal contention initiated by a few male elites can perversely alter the land rights and imagined futures of a diverse array of ordinary citizens, and the implications thereof for studying lawfare and intersectionality in the context of capitalist agrarian transformation in Africa.

The Land Case No. 162 of 2012

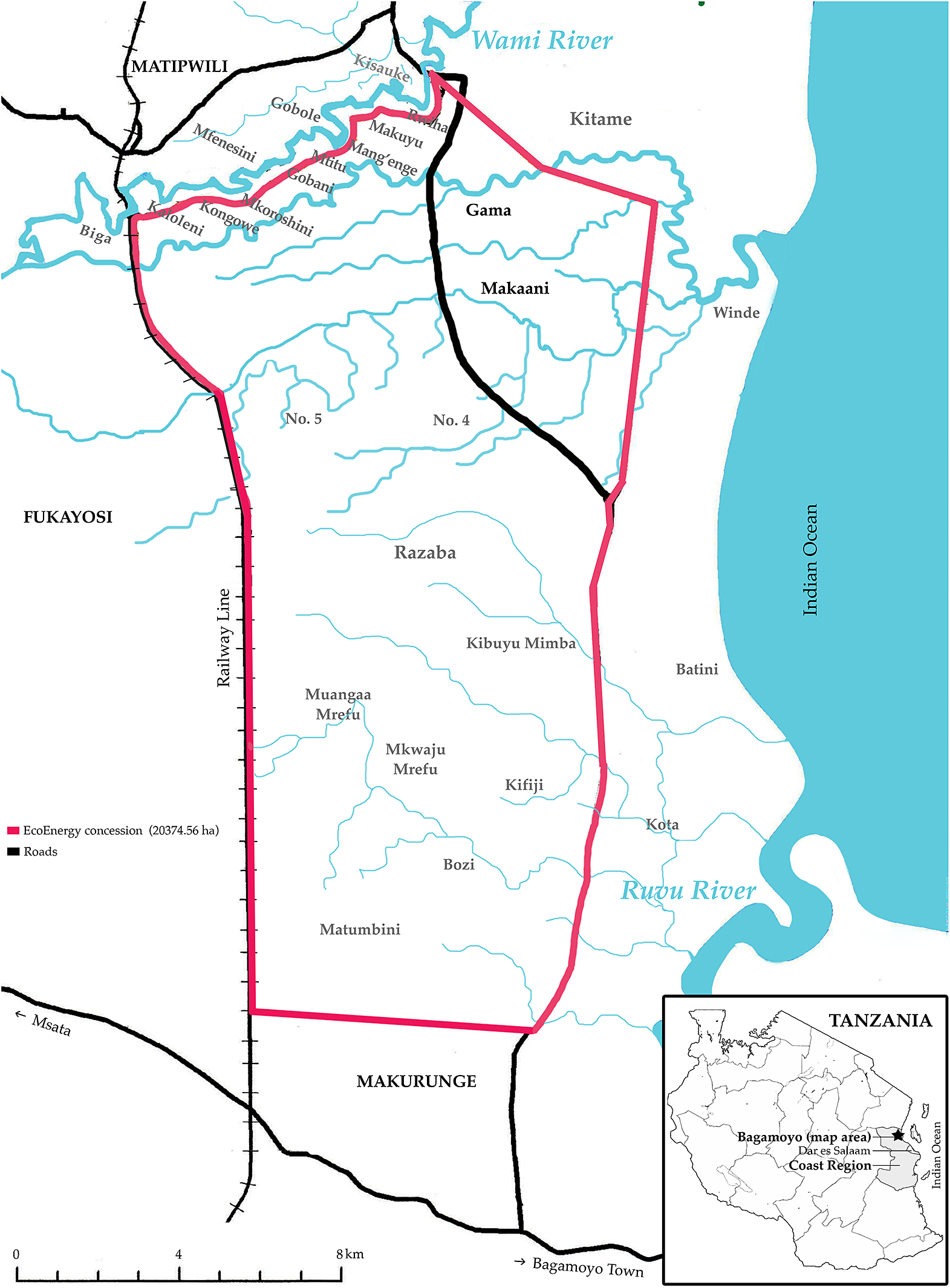

In 2007, the Tanzanian government decided to transfer over 20,000 hectares of land in the coastal district of Bagamoyo to a Swedish company, Agro EcoEnergy Tanzania (hereinafter referred to as EcoEnergy), which had plans to establish a sugarcane plantation and a processing plant.Footnote 2 Although the land transfer was not formalized until 2013, the bulk of the project planning had already been accomplished. Between 2008 and 2011, for example, the project land was surveyed and sub-divided for investment purposes; a nursery was set up to test different varieties of seed cane; soil and water surveys were conducted to assess the yield and irrigation potential of the area; plans for irrigation layouts, bulk water systems, and haulage roads were drafted; an environmental and social impact assessment was approved by the government and lending agencies; and a census of people and assets was partially completed by the government and external consultants to prepare for the displacement and compensation of local residents. While precise numbers are difficult to obtain, it is estimated that approximately 3,000 people stood to be affected by the project. The project was scheduled to begin its first phase of development in the latter half of 2012. At full capacity, it was expected to produce 150,000 tons of sugar, 12,000 cubic meters of ethanol, and over 90,000 megawatt hours of electricity per year. This ambitious plan, however, was interrupted in August 2012, when three male farmers representing an alleged 537 others from Gama-Makaani—a settlement in the northern part of the proposed project site (Figure 1)—filed a trespass suit against EcoEnergy, the Bagamoyo District Council, the Commissioner for Lands, and the Attorney General in the High Court of Tanzania. Hence began the Land Case No. 162 of 2012, hereinafter referred to as the Gama-Makaani case.Footnote 3

Figure 1. Settlements within the EcoEnergy concession area, Bagamoyo District, Coast Region. Map by author

The following key issues framed the lawsuit: 1) that the plaintiffs were lawful owners of various plots of land in Gama-Makaani measuring a total of 6,000 hectares; 2) that the government’s surveying and designation of the land in dispute for investment purposes was null and void; 3) that the government’s granting of the Certificate of Title to EcoEnergy was illegal; and 4) that the plaintiffs deserved to receive TZS four billion (roughly USD two million) in compensation for economic losses due to the defendants’ trespass as well as payments for general damages as determined by the court. Due to reasons of space, this analysis will primarily focus on the first issue, although all four components are interconnected.

While the names Gama, Makaani, Gama-Makaani, and Makaani-Gama are used interchangeably in court documents, there are important distinctions to be made. The land area depicted in Figure 1 has been shaped by contested history and geography (Chung Reference Chung2019). Prior to independence in 1961, the cultivated areas and settlements near the Wami River were collectively known as “Wami,” a name that signified the centrality of land and water for people’s livelihoods. During ujamaa times, especially with the implementation of compulsory villagization in the 1970s, people were forced to move to state-designed villages such as Matipwili, Fukayosi, and Makurunge and engage in collective agriculture. The land, once emptied of people, was converted into a state cattle ranch. When agricultural collectivization and the ranch both failed, people began re-claiming the land and re-establishing settlements in the area. Situated on the low-lying floodplains of the Wami River, Gama is one of the most fertile areas in the river valley, with alluvial deposits suitable for cultivating cereal crops, namely rice and maize, and a variety of vegetables and fruits, including bananas and mangoes. Makaani is drier and higher in elevation, with sandy loam soil, ideal for building houses and planting hardy tubers, legumes, and fruits, such as cashews and papayas. Given these topographical and agroecological variations, most people who maintain their fields in Gama have their residences and small gardens in Makaani and other dry areas such as Kisauke. The shorthand Gama-Makaani thus refers not only to the combined land area of these two places, but also to their historical and geographical relationality. In their charge, the plaintiffs referred to Gama-Makaani as a “village.” It needs clarifying, though, that these are not formalized administrative units; they do not appear in district records, and they have neither government-issued village registration certificates nor government-appointed executive officers. The court did not question this issue, however, and proceeded with the case as follows.Footnote 4

The specifics of the plaintiffs’ land claims were similar yet heterogeneous. The first elder, Salum Yusuf Salum, claimed that he had been living in Gama since his birth in 1946, and that he had inherited 300 acres in the area from his deceased parents. The second elder, Ally Thabiti Ngwega, adduced that he owned a ten-acre farm plot in the disputed area, which he had inherited from his father upon his death in 1988. The third elder, Ally Said, similarly stated that he had inherited eighty-nine acres from his deceased parents and acquired an additional thirty-one acres in the disputed area by clearing pristine land. The rest of the plaintiffs argued that they were owners of various plots of land in the disputed area, ranging from ten to thirty acres, which they claimed to have acquired by clearing bushland between 1986 and 2007, before the arrival of EcoEnergy.

Before I elaborate on the plaintiffs’ background, it is useful to first present the decision of the High Court, which was delivered by Judge Gerald Ndika on November 13, 2015. The upshot was that the Judge dismissed the case with costs, meaning not only that the plaintiffs lost the lawsuit, but that they were now also liable for compensating the defendants for wasting their time and money. The fundamental reason for the dismissal was that the plaintiffs had not provided sufficient and credible evidence to support their claims. The Village Land Act of 1999 adjudicates customary land rights through certificates of customary rights of occupancy and through the performative act of having been in “peaceable, open, and uninterrupted occupation of village land under customary law” for more than twelve years or through legal transactions (URT 1999: Part IV, Section 57[1]). Given that land titles are rare in rural Tanzania, affidavits are acceptable forms of evidence in court. In the present case, only 46 out of the 540 plaintiffs provided evidence to prove their customary land ownership. Moreover, no one had submitted any clear breakdown of the damages said to be worth TZS four billion. Given that the 6,000 hectares in question were not jointly owned by the plaintiffs, and that each claim was independent and heterogeneous, the Judge deemed that it was the duty of each appellant to testify and prove his or her respective land ownership as well as the specifics of the losses incurred. The plaintiffs’ lawyer offered no rebuttal in response to these points.

The fact that the plaintiffs failed to provide adequate evidence and, more importantly, that their lawyer allowed them to proceed with the case despite this critical omission is curious, if not problematic. Beyond this, there were other issues that could qualify as attorney misconduct. The judgment indicates, for example, that one of the witnesses who testified in court was a “legal officer” from the law firm that was representing the plaintiffs. My interviews with the wives indicate that the plaintiffs’ lawyer also had a stake in the lawsuit, resulting from his direct land purchase from the first two plaintiffs. Considering these glaring contradictions, it is not surprising, then, that the case was dismissed with costs. A prominent Tanzanian legal scholar whom I consulted regarding this case suspected that it had been “set up to fail.”Footnote 5 He adduced this further from the fact that the case took only about three years to come to a verdict, whereas typical High Court land cases can take up to, if not more than, ten years to reach resolution.

From the perspective of EcoEnergy, the lawsuit was a political maneuver orchestrated by special interest groups, namely the country’s sugar importers (Agro EcoEnergy Tanzania 2017). The company executives speculated that the male farmers and their lawyer were likely to have been co-opted by these industry players, who risked losing the government’s increased support for domestic production and import substitution of sugar. When I asked for his views on the lawsuit, the Chairman of EcoEnergy insisted: “The [sugar] traders are doing everything they can to obstruct, frustrate, delay, and stop the project. By delaying the project more and more [with the lawsuit], you end up creating more problems for the project.”Footnote 6 Other commentators have also hinted at the role of sugar importers in thwarting the EcoEnergy project and other sugar schemes in the nation, although the evidence has been difficult to verify (see Africa Confidential 2017). When I asked the plaintiffs about how much the lawsuit had cost them and how they were able to raise the funds, they were equivocal in their response, except to note that the fees amounted to several hundred million shillings and that they received support from their fellow villagers and unnamed “sponsors.”Footnote 7

Besides the partiality of evidence, conflict of interest, and the ambiguity of motives of different actors behind the lawsuit, there is another curious and important issue that remained unquestioned and unanswered during the litigation process: the absence or the exclusion of the plaintiffs’ wives and hundreds of other legitimate land users from the lawsuit. The next section elaborates on the identities of the plaintiffs and how their privileged social locations enabled their exclusionary lawfare. The focus here is on the story of the first two plaintiffs, not only because of their leading role in the lawsuit, but also because the third plaintiff was absent from Bagamoyo due to illness during the period of my fieldwork; according to court documents, he also did not testify in court or offer any evidence to support his land claims. An ethnographic investigation into the intersectional politics of exclusion illuminates the complex relations of power that shaped the making of the Gama-Makaani case and the ramifications of its premature dismissal.

Intersectional Politics of Exclusion

Plaintiff 1: Bambadi

The first plaintiff, Salum Yusuf Salum, seldom went by his formal name, but rather by his nickname, Bambadi. With “bamba” in Swahili meaning “to arrest, catch, or hold,” the moniker implied that he was a troublemaker. He was tall, loud, and heavy-built. He was not fazed by his roguish epithet; during our first interview in August 2014, he introduced himself as Bambadi, laughing and beating his chest with pride. Many women and the youth in the area regarded Bambadi with a mix of deference and fear, by virtue of his gender, seniority, and political status, as well as his fiery temperament. He was almost always seen in the company of other men, often wearing a green and yellow cap and T-shirt, signaling his leadership role in Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), the ruling political party. When asked about his political motivation during an interview, Bambadi drew on the rhetoric of then incumbent President John Pombe Magufuli and his election slogan “hapa kazi tu” (roughly translated as “only work here”) to highlight his commitment to hard work to promote community development in Makaani.Footnote 8

His neighbors, however, rejected his stated motive. They contended that his primary goal was to accumulate power and wealth by brokering land sales to various “strangers.” Some speculated he was selling land to outsiders to increase the total number of bodies occupying Makaani, so as to make it physically difficult for EcoEnergy and the Tanzanian government to clear the land. Long-term residents condemned Bambadi for selling land not only in Makaani, but also in other neighboring areas, including those in the fertile river valleys of the Wami River. These areas had been occupied and used by generations of family farmers, and most recently, earmarked by EcoEnergy as the prime location for irrigated sugarcane production (Chung Reference Chung2019). “We fought so hard with Bambadi when he was trying to sell our land to rich people in Dar [es Salaam]. And then, EcoEnergy came and tried to take our land!” said one forty-three-year-old female farmer.Footnote 9 On the whole, Bambadi was seen as appropriating his leadership position in the local CCM party cell, as well as his moral authority linked to his seniority and long-term residency, to justify his land sales. However, his purported loyalty to CCM was challenged by several people, especially other long-term residents who were opposed to the lawsuit from the outset. As one fifty-one-year-old male farmer stated in an interview: “Bambadi is just using ujanja ujanja [tricks, deceit]. You know, they [Bambadi and his co-plaintiffs] have membership cards for more than three political parties. They plant CCM flags in front of their houses, but that is just a cover.”Footnote 10

Based on observations and interviews, Bambadi’s clientele for land sales likely comprised two key groups: poor landless migrant farmers and wealthy urban elites. The first group was presumably an easy target for Bambadi, considering the continued influx of newcomers into the area since 2010, when news of the EcoEnergy project spread. Some of these migrants came to Bagamoyo from as far as Kigoma in western Tanzania in anticipation of job opportunities, while others, especially landless farmers, migrated in search of what I am calling a “Coastal Dream,” seeking access to fertile lands, abundant waters, and easy markets. While the majority of these migrants were young men, some were divorcées and single mothers who came to the area in search of farmland after having struggled to make ends meet in the countryside and in the urban fringes of Dar es Salaam. Most of these migrants related having met with Bambadi at one point or another. For example, one fifty-three-year-old male farmer who had migrated from Iringa noted that when he first arrived in Makaani through word of mouth in 2011, he went to see Bambadi to introduce himself and to request an allocation of land. When asked why it was important for him to make himself known to Bambadi, he responded:

I didn’t know who he was, but he was an elder, and he said he was the local village leader and CCM leader. As long as he is an elder, a newcomer like me just assumes he knows about land matters around here from the past. He was pleased I was coming to the area to farm and gave me two and a half acres for free.Footnote 11

While this man and several other young male migrants were given land for free as long as they cleared and used it, others, including single mothers, divorcées, and widows, noted they had to pay a fee to Bambadi, anywhere between TZS2,500 and 5,000. One migrant widow in her mid-sixties said she had no other option but to pay Bambadi if she wanted to “find life.”

I came here from Kigoma in 2004. My husband passed away in 2001; his brothers allowed the land to be divided among multiple wives, but I received nothing. I first moved to Dar [es Salaam], but life there was very bad and so I came here to find life. I paid Bambadi TZS2,500. I knew having land would help me push on with life, even though I still find myself struggling.Footnote 12

Bambadi’s land sales to wealthy urbanites were more elusive to trace, but they were revealed to me one afternoon, when I was invited to his home to discuss the verdict from the High Court. As we got seated around a plastic table outside his house, he told me he was going to appeal the judgment. But before I could ask further questions about his plan of appeal, we were interrupted by a small white truck approaching from the direction of Bagamoyo Town. The truck eventually stopped in front of Bambadi’s house. A middle-aged woman in modern attire, with sleeveless shirt and smart trousers, shiny jewelry, a shoulder bag, and platform sandals, accompanied by a young, equally well-dressed male driver, disembarked from the vehicle and walked toward us. Their visit seemed unexpected; Bambadi got up from his chair and unceremoniously introduced the visitors to me as “wenyeji (local people/natives of the area),” and me to them as an “mtafiti (researcher).” The woman smiled and said she owned a watermelon farm in Gama and that she was just passing by to say hello to the elder. In an effort to make small talk, I asked whether she was one of the locals who supported Bambadi’s lawsuit. As she smiled and nodded, Bambadi quickly intervened: “When you cheat people, you get followers. And when you have many people who feel cheated, it is easy to get followers.”Footnote 13 After what felt like an awkward exchange, Bambadi escorted his guests inside the house, leaving me alone behind by the table where he and I had been seated.

Hadija, Bambadi’s fifty-five-year-old wife, motioned me to join her in the kitchen, where she was making a big pot of maize ugali (thick porridge). Bambadi and the visitors reemerged shortly afterwards, boarded the truck, and left, saying they needed to do “farm visits.” Hadija continued boiling the water for ugali, and when the truck was finally out of sight, she told me, unsolicited, that the visitors were from Mbezi, a neighborhood in Dar es Salaam, and that she had seen them before when they came to “look for land,” revealing that Bambadi had been involved in land brokerage. I seized the rare opportunity to interview Hadija in the absence of Bambadi while waiting for him to return. However, after a series of basic questions, it became apparent that Bambadi had shared little information about the court case with his wife. Perhaps exasperated by her own repeated articulations of “I-don’t-knows,” Hadija explained:

If I look around, women around here are losing a lot. Women are invisible. I don’t really know why… maybe because we haven’t studied. But even if we have studied, we are being cheated. Women are being oppressed by their husbands, brothers-in-laws, and etc. I am a Zigua [a historically matrilineal-matrilocal ethnic group] from Mkange… Here comes the problem. I came all the way here from Mkange for marriage. Bambadi is a Doe [a historically patrilineal-patrilocal ethnic group], so I had to come live with him. But here, I have no relatives. I have to rely solely on my husband, including land. Even if I get a divorce, I cannot force him to divide the land equally… It’s like women are owned by men, and men are responsible for everything.Footnote 14

As her quote suggests, while she was hardly involved in the court case, she was well aware that her access to land critically depended on her marriage to Bambadi and on the lawsuit. When they got married, Bambadi had given her permission to grow food crops and vegetables on eight acres of land behind their house, although she could only farm up to two acres by herself. She was unsure how much land Bambadi owned or claimed that he owned, but she indicated that he operated a “big farm” in Gama with hired laborers, which was not an option for most poor smallholders in the area.

In his oral testimony in court, Bambadi was vague about when and how he came to inherit 300 acres of land. He simply stated that he was born, raised, and educated in the area and that his parents were laid to rest there. His statement was refuted by the defendants and ultimately rejected by the judge on the grounds that there was no material evidence to prove his claims. In my interviews with other local elders who were born and raised in the area, but who were uninvolved in the lawsuit, they emphasized that it was impossible for Bambadi, or for any villager for that matter, to have inherited a tract of land as vast as 300 acres. Indeed, the median landholding per household among the 176 households I interviewed across the EcoEnergy concession area was three acres. Given the general contempt his wife and other villagers harbored toward his patriarchal authority and his track record of misdeeds, it is plausible that Bambadi and his allies found it risky to include them in the lawsuit; the fewer people who were capable of questioning his claims, the better. The next section sheds further light as to why exclusionary politics remained so central to the male elders’ lawfare.

Plaintiff 2: Thabiti

The second plaintiff, Ally Thabiti Ngwega (more commonly known as Thabiti) was patient and calm in his demeanor, and he attracted less notoriety than Bambadi. He was two years Bambadi’s senior and was almost always seen wearing an Islamic kanzu (long-sleeved full-length gown) and kofia (embroidered cap), rather than the green and yellow CCM attire, although he was also active in local party leadership. While most people disparaged Bambadi for engaging in illegal land sales, Thabiti was also complicit in the act, as his seventy-seven-year-old wife Fatuma affirmed. Like Hadija, Fatuma could say little about the origins or the details of the court case, but she was cognizant of its covert nature. As she explained in an interview:

I used to ask [Thabiti] about the case, but he would hide his papers. So did Bambadi. But from what I know, the 500 people who joined the case were from Dar [es Salaam]. They were given land by Thabiti and Bambadi. Oh! Even the lawyer bought a farm here, although I have never seen him use it! [laughs] The lawyer came here maybe twice. It is mostly Bambadi and Thabiti who are called into meetings with the lawyer in Dar. Sometimes at night, when my husband’s phone rings, I lay wondering whether someone has died, but it is nothing like that. He is just being called into another meeting in Dar with the lawyer or with someone else. It would have been good if the lawyer and judge had come here to talk to me. I don’t know if any women here are involved…Footnote 15

Fatuma’s testimony is important for at least two reasons. First, she highlights that the 537 co-plaintiffs who joined Bambadi and Thabiti were not actual “local” residents. In fact, a review of the names of plaintiffs who submitted affidavits of land ownership indicated that a good number of them were of Chaga origin, one of the wealthiest and the most educated ethnic groups in Tanzania, and unlikely constituents of rural Bagamoyo. Second, when asked to elaborate on why she wished the lawyer and the judge had come to speak with her, Fatuma disclosed information that was contrary to what Thabiti had testified in court. In his oral testimony, he stated that he had inherited ten acres of farmland from his father in 2007. Unlike Bambadi, who had appealed to his birthright to shore up his customary land claims, Thabiti abstained from sharing any personal details about his life in the courtroom. Neither did he wish to discuss it with me during interviews except to say that he was born in 1944 and that he has lived in the area for a “long time.”

According to Fatuma, however, the ten-acre farm which Thabiti claimed was his, was in fact hers. It was land which she had inherited from her parents, who passed away in the 1950s. Her late father had been a migrant laborer, working in various coastal colonial plantations from Lindi to Tanga, until he finally settled in Bagamoyo in the late 1920s. I quote her story at length below, because it demonstrates how her claim to land ownership is deeply rooted in and articulated through the interconnected histories of family life, the colonial migrant labor system, and struggles for livelihoods and belonging. By demonstrating how places and their meanings come to matter through complex entanglements of history, culture, and power, she highlights the limits of customary land claims that are based solely on the labor theory of property adduced by the plaintiffs.

My father was a Makua born in Masasi when the Germans came to rule Tanganyika. After finishing school, he moved to Lindi, and worked at a salt mine as a migrant laborer. Later, his boss transferred him to Kunduchi in Dar to work at a sisal plantation. My maternal uncle worked there at the same plantation as a messenger, delivering letters.

One day, my mother went to visit her brother in Kunduchi. When my father saw her, he was immediately smitten. He asked people: “Who is that girl? To whom does she belong?” These things of men… [laughs] When he found out that she was related to the plantation messenger, he asked my uncle: “I want to marry your sister.” My uncle replied: “I don’t have authority to give her to you. Go to my father in Tunduru.” So he did. My mother was very young when she got married, maybe 15 or younger…

After a while the wazungu [Europeans] transferred my father again from Kunduchi to another plantation in Muheza in Tanga. My father had a three-year contract there. After three years, he was transferred to another plantation within Muheza, called Kicheba, which white South Africans owned. Our family spent many years in Kicheba. My mother gave birth to 8 out of 12 children there, including me. But my father lost his job when the South Africans went back to their country.

My father had three maternal uncles at that time living in Bagamoyo. These uncles were originally hunters who were sent from Masasi to Bagamoyo to hunt elephants for the Arabs. This was a long time ago. When they first came to this area, they decided to call it Makaani, which in their vernacular meant “to stay,” like the Swahili “kaaeni,” which means “let us stay.” After awhile, they decided to move closer to the Wami River, where it was better for growing food.

When my father lost his job in Kicheba, his uncles urged him to come visit. They were unhappy because my father had stayed in Tanga for far too long; they thought it was better for family to live closer. My father was worried: “But how can I [move]? I have my family and coconut trees here in Tanga.” But he could not disobey his uncles’ wishes. When he eventually moved to this area around the late 1920s, he got a job at the Greek-owned sisal estate in Kisauke. My father worked there for a long, long time… After a few years of working there, he decided to bring his wife and children from Tanga. The uncles gave my parents ten acres to farm in Gama. Those areas [Kisauke, Gama, Makaani] were known as Wami back then…. Later, when my parents died, they gave the land to me. I know that it is my parents’ land because they planted a tall mvumo [African fan palm] there, which still stands to this day.Footnote 16

In 1972, Fatuma married Thabiti, who was then a contract laborer at a British-owned salt mine in Kitame to the northeast of Gama. She recalled that at the time of their marriage, Thabiti was a migrant worker with no land or family ties in Bagamoyo: “He is a Pogoro from Morogoro who came to Bagamoyo for work. His parents visited once in the late 1970s, but neither of them lived long after that.” Because Thabiti had no access to farmland of his own, he relied on Fatuma’s family land and her labor to provide food for the family once they married.

Despite the centrality of Fatuma and her family history to Thabiti’s land access, her testimonies never made it into the courtroom. At best, her entitlements were misappropriated by or subsumed under the authority of her husband. Her existence and land rights—let alone those of Bambadi’s wife and numerous other legitimate landholders—remained unquestioned either by the judge or the lawyers on both sides of the case. Yet, what is not said is equally critical to understanding how power works. On the one hand, the elders’ lawfare and the exclusionary practices that undergirded it demonstrate the everyday operations of elite male power at both the household and community level. On the other hand, the failure of the lawyers and the judge to consider the possibility that the elders might have family members with independent and differential land claims reflects what other feminist scholars and lawyers have highlighted as the deeply-ingrained patriarchal disposition of the Tanzanian judiciary as a key arena of state power (see Hodgson Reference Hodgson1996; TAWLA 2013).

The Aftermath

The news of the High Court ruling traveled fast, thanks in part to EcoEnergy’s public relations efforts. In February 2016, the company distributed a one-page circular to various communities within the planned project area beyond Gama-Makaani. Some people found the memo pegged to a tree, while others received individual notices firsthand from their local leaders or secondhand from their neighbors. Other people described how a young Tanzanian EcoEnergy employee came on a motorbike and threw the papers in the air as if to celebrate the outcome. Summarizing the verdict, the memo stated that Gama-Makaani was legal property of EcoEnergy. While the outcome was still contestable, that much was understood by the local people. However, the remainder of the notice was troubling, because it named the elders, their co-plaintiffs, as well as “all persons living within the project area” as “invaders,” and stated that they were “expected to take proper action according to the law and decision of the court.” That is, all current residents were expected to voluntarily leave the land, presumably without compensation, and resettle elsewhere to avoid forced eviction.

The timing of this announcement coincided with the spread of rumors about how all settlements within the land concession would be bulldozed by the government. Shortly thereafter, a local election which was scheduled to take place was suddenly halted by the District Commissioner. Neither the ward councilor nor the candidates were given clear reasons for the suspension, although they speculated it had to be related to the Gama-Makaani case. People were outraged by their sudden and unwitting disenfranchisement, and quickly blamed the male elders for diminishing their status and reducing them to mere squatters. As one thirty-three-year-old male farmer said angrily in an interview:

The reason we are now called invaders is all because of the court case. But we were not involved in the case! And I have been living here for the past thirty years! Everyone here knows that those 500 people who supported Bambadi and Thabiti are from Dar [es Salaam]. It’s like this, sister—you see, one fish is rotten in a bucket; that one fish is bad enough to make all the other fish look rotten! Back then when EcoEnergy counted us and promised compensation, I was skeptical. I didn’t think they would pay us, but they kept promising, so I started to build some hope. Now, I don’t know if that’s even a possibility.Footnote 17

Similar concerns were raised by others who felt their prospects and possibilities on the land had been cut short by the elders. One thirty-nine-year-old female farmer and single mother, for example, expressed her anxieties about remaining on the land, and regretted having trusted in Bambadi and his moral authority as a male elder:

When I first came here in 2009, I couldn’t send my eight-year-old daughter to school because there wasn’t a school in Makaani. Bambadi promised young mothers like me that he would bring a teacher into our community. Later he said we each had to pay TZS12,000 per family to pay the teacher, which I couldn’t afford to pay. I thought he was doing the court case for our community development. But now I’m not sure what his intentions were, and I don’t know what will happen to my life now. I am scared. I am just waiting for things to pass and get better.Footnote 18

Hadija and Fatuma were equally dismayed by the court’s decision. Soon after the judgment was made public, I asked them in separate interviews how they thought the verdict might affect their lives. Hadija first gave a nonchalant shrug and said it had become “normal to live with uncertainty.” But soon after, she pondered whether it would be better for her to divorce Bambadi and return to her home village where her relatives lived and where she knew she had some inherited land, though it had been a while since her last visit. Yet, upon realizing she could not divorce Bambadi on her own accord alone, she said half-jokingly and half-serious: “If there is another woman who wants to take my husband, she is more than welcome to!”Footnote 19 Fatuma, on the other hand, regretted again how she could not tell her side of the story. Rubbing the pronounced edema on her right leg and foot, she said:

Thabiti did not even ask me if I wanted to be involved in the court case. I have a lot of stories to tell. But I have trouble with my feet. Sometimes I can’t even feel my feet as if they are paralyzed. To get from here to there [pointing to a distance a few feet away], I need to stop two to three times. I wish the judge had come spoken with me…Footnote 20

In sum, the elders’ loss did not seem surprising to many. What they were aggrieved by, however, was how they were inadvertently disenfranchised and dispossessed in situ as a result of the elders’ lawfare, which they had opposed, were excluded from, or knew little about from the beginning.

Conclusion

The fact that a few farmers in Tanzania managed to sue the national government and a foreign investor to cease the enclosure of their land is not insignificant, especially in light of the general reluctance rural people have to use the court system to access their rights. For those who decide to pursue legal action, the allure of law may be that it appears to provide “a ready means of commensuration” (Comaroff & Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2006:32), or a set of more or less standardized tools and practices for negotiating divergent, competing, and at times impermeable claims. The way that the plaintiffs justified their case echoed this idea of commensurability; they contended they were using the court system to resist what they perceived to be unlawful trespass on their land by powerful actors.

Yet, as I demonstrated in this article, this semblance of benign legal resistance belied many contradictions, slippages, and exclusions that simultaneously enabled and undermined the lawsuit. Through a careful examination of what was said in the court room, as well as what remained unspoken and invisible, the plaintiffs’ action may be appropriately understood as an exercise of lawfare from below: the use or misuse of law by elites among the poor to seize opportunities for personal gain at the expense of many. While ambiguities still remain about the motives of the plaintiffs as well as those of their undeclared allies, what is clear from the foregoing analysis is that lawfare is fundamentally shaped by, and shapes, intersecting inequalities. The plaintiffs drew on their multiple positions of privilege to mobilize resources from external actors and to exclude from the lawsuit diverse legitimate resource users, across the differences of gender, class, generation, and social status.

The lawsuit, understood as lawfare, was not only perverse in its design and outcome but also in its unintended consequences. While the plaintiffs were successful in delaying the implementation of the land deal through an initial court injunction, this delay and the ultimate failure of the lawsuit rendered local people—irrespective of their involvement in the case—more vulnerable to dispossession. The restrictions on civil and political rights and the imminent threat of displacement also laid bare the marginality of the rural poor vis-à-vis the state and the foreign investor. People were unwittingly thrust into a condition of liminality, where they had to negotiate their subjectivities as rightful landholders and citizens on the one hand, and the externally-imposed identities as squatters and invaders on the other, all because of, to borrow from the interviewee above, a few “rotten” elites. Ultimately, the social disarticulation that resulted from the lawfare deepened existing fault lines and intersecting inequalities within and among the “local” itself, between elites and commoners, large and small landholders, residents and migrants, older and younger generations, men and women, and husbands and wives.

Would the outcome of the case have been any different if the plaintiffs had been more diverse and inclusive in representation, if witness testimonies had centered more on people’s lived histories on the land, and if the case had been prepared more robustly by an attorney with no conflict of interest? Perhaps. But it would be naïve to ignore the violence inherent in the law; as this article has highlighted, access to law is unevenly distributed, and the dispersal of land politics into the legal sphere does not promise justice or redress. More law does not necessarily lead to less conflict; the fact that the number of land disputes seems to be rising in Tanzania despite land law reforms over the past two decades may be indicative of this paradox. In sum, the findings of this study signal the need for more critical analysis of lawfare and intersectionality as part and parcel of land and agrarian politics in Africa. Methodologically, this would require an ethnographic sensibility that attends to silent and hidden operations of power, and one that is grounded in the lived experiences of difference and marginality.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Social Science Research Council and various institutions at Cornell University, including the Einaudi Center for International Studies, the Institute for the Social Sciences, the Institute for African Development, and the Center for the Study of Inequality. I owe special thanks to my interlocuters in Bagamoyo for their time and insights, and to Francis Shang’a for his research assistance. I wish to thank Ross Doll, Asher Ghertner, and Marie Gagné for their helpful comments on earlier drafts. Thanks also to Ashley Fent and Alicia Lazzarini for organizing a session at the American Association of Geographers annual meeting in 2018, where I presented an earlier version of the paper. Finally, I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers and editors at the African Studies Review whose careful reading and critique strengthened the manuscript.