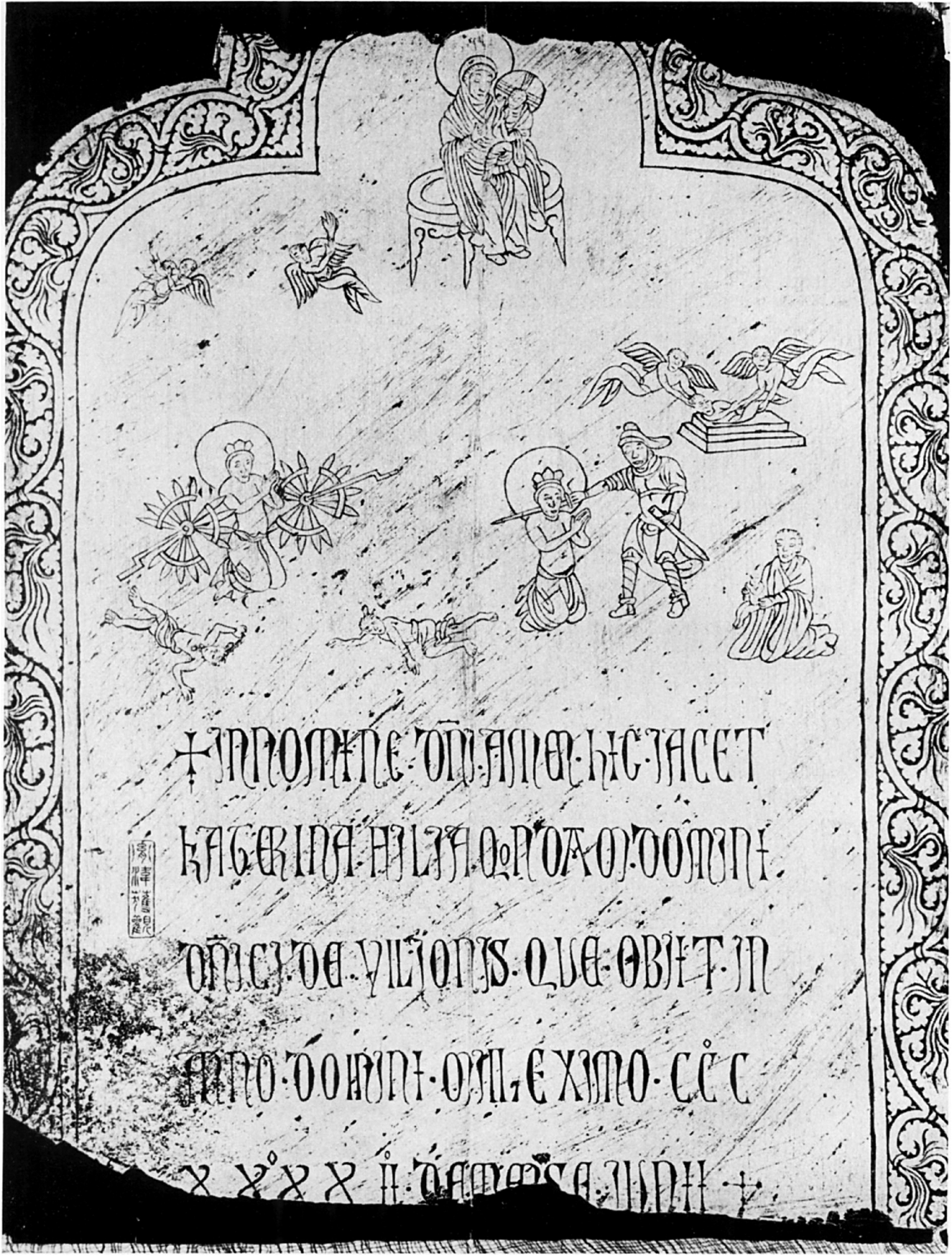

In 1951, a late medieval Christian tombstone with Latin inscriptions was discovered during road construction at the South Gate of Yangzhou (扬州市) in current-day Jiangsu province in eastern China (Figures 1 and 2).Footnote 1 It survives in excellent condition, and only the top and the bottom of the grey stone slab have been damaged. The upper half of the funerary monument is decorated with low-carved reliefs depicting the enthroned Virgin Mary and Child above scenes from the martyrdom of St Catherine of Alexandria. According to the Latin inscription written with Gothic majuscules, the stone slab commemorated the death of Caterina Vilioni, daughter of Domenico Vilioni, in June 1342.Footnote 2 While no other surviving written sources attest to the existence of Caterina Vilioni, her funerary monument is a rare and important testimony to the presence of western European Christianity in Yuan China (1271–1368).

Figure 1. Caterina Vilioni's tombstone, 1342. Granite, h: 58 cm. Yangzhou: Marco Polo Museum. (Photo: Deborah Howard.)

Figure 2. Copy of Caterina Vilioni's tombstone. Negative reproduction of the facsimile of the original rubbing made in 1951. (Image: Rouleau, ‘Yangchow’, plate 2.)

Significant recent scholarly interest has sought to understand more fully the integration and perception of foreigners in medieval European cities.Footnote 3 The present article turns this concept upside down by investigating European Christians as strangers in one of the largest cities of fourteenth-century east China. Caterina's tombstone was found near to that of her brother, Antonio Vilioni.Footnote 4 Theirs are two of only three western Christian tombstones that survive from Yuan China. The mention of their late father as a resident of Yanghzhou on both tombstones demonstrates that their presence was far from transitory. The Vilioni family had been based in the city for some time. As a woman's tomb, Caterina's is of special importance. The expansion of European networks towards the east has been written from the perspective of men: friars, diplomats and merchants.Footnote 5 This is hardly surprising, however, since the extant written sources privilege male perspectives. The example of Tamta, an Armenian noblewoman from the circle of Queen Tamar of Georgia whose travel to Mongolia between 1236 and 1245 is only briefly noted in the sources, demonstrates the limited nature of the information that survives about the voyages of female Christians in the Mongol empire, even when they belonged to the top echelons of society.Footnote 6 Most often, not even their names were recorded. The wife of the French goldsmith Guillaume Boucher, whom the Mongols forcibly brought to Kharakorum in the 1240s, is described only as ‘a Lotharingian woman born in Hungary’.Footnote 7 In contrast, Caterina Vilioni's tombstone offers a tangible legacy and opens a unique window onto the presence and patronage of non-elite European Christian women in premodern China.

Caterina's gravestone was first published in an article by the sinologist and Jesuit priest Francis Rouleau shortly after its discovery.Footnote 8 More recent work by Lauren Arnold and Jennifer Purtle sought to identify whether certain features of the iconography originated either from Buddhist or from Christian art.Footnote 9 In an analogous way, Eva Caramello and Romedio Schmitz-Esser aimed to determine whether the epigraphic features of the inscription were either in line with north Italian practice or defined by the ‘influence of Chinese characters’.Footnote 10 The present article shifts the attention to the cultural ambiguity of the visual context and argues that numerous features of the imagery were designed to be intentionally ambiguous. These elements were intelligible both for local Chinese and for European Christian viewers, which ultimately helped to contextualise Caterina Vilioni's identity in Yangzhou not only as a stranger, but also as a stranger who had put down roots in this strange land and made it her home. By exploring the visual language and the multicultural geopolitical context of Caterina's tombstone, this article sheds light on the dynamic processes of how cultural barriers were negotiated in premodern Eurasia.

At stake here is how the practice of cultural translation could serve, not as a hindrance to pinpointing the origin of particular features of a composite object, but as a useful interpretative vector in its own right. By examining fifteenth- and sixteenth-century ‘Veneto-Saracenic’ objects, crafted in Venice with a deliberate attempt to emulate Levantine prototypes, Elizabeth Rodini proposed that we move beyond traditional classifications preoccupied with ‘origin’ and place of production and instead focus on ‘mobility’ as a category of value.Footnote 11 This approach highlights a problem central to the fledgling field of the Global Middle Ages, in which artefacts are often pigeonholed in inflexible interpretative processes of influence, adaptation and hybridity.Footnote 12 The Yangzhou tombstone not only eludes rigid categorisations in the traditional frameworks of stylistic and iconographical analysis but also calls attention to objects which deliberately communicated ambiguous messages. This raises crucial questions both about Caterina's identity and about the potential multi-ethnic and -confessional viewership of her funerary monument. Indeed, we must consider whether even Chinese Christian beholders would interpret the imagery along the same lines as European Christians.

Looking at Yangzhou through the eyes of Caterina Vilioni therefore broadens our understanding of the presence of both western and native Christians in the Yuan. The intertwined relationship between Buddhism and Islam has attracted much of the scholarly spotlight on religious plurality in east Asia.Footnote 13 Christian denominations, however, also gained followers.Footnote 14 Previous scholars have analysed in detail the early expansion of the East Syrian Church during the Tang Dynasty (618–907).Footnote 15 The early modern and modern Roman Catholic missions spearheaded by the Jesuit brethren in Beijing, Macau, and elsewhere have similarly been extensively studied.Footnote 16 Examining the case of a Roman Catholic woman in fourteenth-century Yangzhou will throw much-needed light on the intermittent period between the pre-tenth century and the modern context of the development of Christianity in China.

Religion aside, there is another reason why Caterina's tomb is worthy of our attention. Since she hailed from an Italian mercantile family, her story is also intertwined with medieval trade. Scholars have explored in great depth the ever-increasing demand of late medieval Europeans for luxury goods imported from Asia along the Silk Roads. Sumptuous silk fabrics interwoven with gold thread, such as panni tartarici or tatar fabrics are some of the best known facets of this intercontinental luxury trade.Footnote 17 The intricate blue-and-white porcelains manufactured in the famous Jingdezhen kilns were also highly prized by the wealthiest layers of European courtly society.Footnote 18 Moreover, artistic raw materials such as mother-of-pearl, coconut and exotic seashells also found their ways to the west where they were fashioned into lustrous containers, reliquaries and drinking vessels by local European craftsmen.Footnote 19 The trade of perishable merchandise, such as spices, coconut and plants imbued with medicinal properties, has received particular attention.Footnote 20 However, despite all of this interest in the European import of Asian merchandise, movement of objects in the opposite direction, namely from Europe to Asia, is much less explored. Moreover, despite a few famous European travellers such as Marco Polo, it is generally accepted that commerce along the Silk Roads was structured through a chain of middlemen.Footnote 21 The presence of the Vilioni family in Yangzhou, however, raises the possibility of more direct routes of exchange between Asia and Europe than is often supposed.

After introducing the development of Christianity in premodern China, this article will focus on three key points. Firstly, it will examine the surviving written sources about the Vilioni family and trace their origins to Venice. This will also facilitate a broader contextualisation of the expansion of north Italian mercantile networks to the East China Sea. Secondly, through an in-depth consideration of the shape, composition and details of the imagery on Caterina's tombstone, I will argue that the visual language intentionally projected cultural ambiguity. By comparing the tomb to Mongol paiza, a distinctive form of safe conduct passes, the third and final section will propose that Caterina's burial marker functioned as an ‘otherworldly passport’, which invoked spiritual protection and facilitated the passage between two realms. Traversing boundaries and tracing movement are therefore key methodological platforms that underpin this study. This passage is manifested both through examining the movement of living flesh and blood bodies across great physical distances and between widely different cultures and societies, and also through the crossing of the supernatural passageways between this world and the next.

Christian objects in premodern China

To illuminate the broader historical and visual setting of the Vilioni tombstone, we should first briefly consider the early development of the Church of the East (whose members are sometimes also called Nestorian Christians), with particular attention to its material legacy.Footnote 22 Despite the predominance of Buddhism, Christianity was present in China sporadically by at least the seventh century.Footnote 23 The appearance of Christianity in Tang China can be set in the broader context of the spread of the religion in Central Asia along the Silk Roads. The Church of the East found fertile soil in Sogdiana in parallel to its Chinese expansion.Footnote 24 Moreover, the Uighur Khaghanate in the north accepted Manichaeism as its official religion in the eighth century, which amalgamated certain common devotional threads from Christianity and represented another facet of the same vehicle of Iranian culture and language in Central Asia.Footnote 25

The Xi'an stele erected in a monastery near the Tang imperial city of Chang'an (now Xi'an) in 781 is a key piece of evidence for tracing the early history of Chinese Christianity.Footnote 26 The Syriac and Chinese inscriptions commemorate the spread of jingjiao (景教) or ‘luminous teaching’ originating from Da Qin (大秦) or ‘the west’, which is traditionally identified as the Christian faith. The origins of the Christian Church of the East (or East Syrian Church) had close ties with the Sassanian empire.Footnote 27 The Xi'an stele narrates the arrival of Alouben from the patriarchate in Seleucia-Ctesiphon and other Syro-Persian missionaries who brought sacred texts and images with them to China in the ninth year of Emperor Taizong (Tai Tsung) in 635.Footnote 28 The multivalent cultural connotations are further highlighted by the fact that the donor of the stele was the son of a priest originating from Balkh in Afghanistan.Footnote 29

Further important testimony to the early history of the Syriac Christian Church comes from the Luoyang pillar. After the pillar had disappeared for decades on the black market, its rediscovery in 2006 generated substantial scholarly interest in specialist circles.Footnote 30 Luoyang is east of Chang'an and served as an auxiliary eastern capital for most of the Tang dynasty. The octagonal pillar, which resembles Buddhist dhārāṇi pillars, was erected in 829 as a funerary monument of a certain An, a Sogdian Christian woman, and an unnamed deceased uncle of the donor. While the second part of the inscription is a memorial epitaph associated with the funerary context, the first part contains a sūtra on the ‘Origins of the Da Qin Luminous Religion’.Footnote 31 The Luoyang pillar and the Xi'an stele were probably both buried in 845, when all foreign religious institutions including Buddhist ones were attacked. While this was a major blow for Christianity, further evidence attests to the continuation of Christianity throughout the Tang period.

The surviving material is far from being limited to funerary art.Footnote 32 Three fragmentary murals representing New Testament scenes were discovered in the early twentieth century in the remnants of what appears to have been a Christian church in Qocho (Gaochang), the ancient oasis city on the northern rim of the Taklamakan Desert in modern-day Xinjiang.Footnote 33 The Tang-dynasty wall paintings, probably remnants of a larger Christological cycle, depict Palm Sunday, Repentance and Entry into Jerusalem (lost). Just as remarkable was the discovery of a large ninth-century silk painting in the Dunhuang Caves (Cave 17) in 1906–8.Footnote 34 The silk painting shows Christ or a Christian holy figure in a crimson robe with a cross on his chest, wearing a headdress adorned with another cross.Footnote 35 The saint raises his other hand in benediction, a gesture similar to the Buddhist mudra.Footnote 36

While some material evidence therefore attests to elite patronage for the Tang dynasty, historical or literary sources remain extremely scarce until the Yuan period – Caterina Vilioni's time.Footnote 37 Between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, all of China was incorporated into the Mongol empire, which stretched at its height from Korea to the Kingdom of Hungary, and from the Siberian steppe to Burma and Iraq.Footnote 38 The relative stability brought by the Mongol conquest facilitated increased cultural, social and mercantile interactions across these vast polities, which is often characterised as the ‘Pax Mongolica’.Footnote 39 The Mongol empire is also known for its religious tolerance. The founder of the Yuan dynasty Khubilai Khan (r. 1260–94) and the Il-khanid ruler Hülegü Khan (r. 1256–65), both sons of the Turkic (Keraite) Christian princess Sorghaghtani Beki, were known for their Christian sympathies.Footnote 40 In 1289, the so-called Office of the Christian Clergy or Chongfusi was established to monitor the Church of the East and other foreign religious communities in China.Footnote 41 The History of the Yuan Dynasty reports that a certain Jesus the Christian and Interpreter headed the office in 1291.Footnote 42 After his death in 1308, his son Elias succeeded him. While we still have only a rudimentary understanding of its organisation and mechanisms, the Chongfusi's objective seems to have reached beyond simply administrating religious groups and probably also involved supervising foreign minorities. Moreover, there were also personal overlaps between the religious minorities. The bilingual Uighur-Chinese tombstone of the Christian Mar Solomon (d. 1313) indicates that he, perhaps in connection with the local religious office, led both the Christian and the Manichean congregations in the major cosmopolitan port city of Quanzhou.Footnote 43

After 1276 a new social policy instituted preferential discrimination for non-ethnic Chinese, which served to consolidate the high social status of the Mongol ruling class.Footnote 44 This ranked the people into four classes in descending order: (1) Mongols, (2) non-Mongol, non-Chinese foreigners (semu ren), (3) Northern Chinese (bei ren), and finally (4) Southern Chinese (nan ren).Footnote 45 While designed to favour Mongols, the policy also benefited semu ren, who quickly assumed important positions of authority in Yuan China. This preferential ethnic discrimination encouraged the arrival of additional foreigners, including Roman Catholic priests, merchants (like the Vilioni) and diplomats from western Europe.

Practically all the documented early travellers are men, either friars or merchants. The Venetian merchant Marco Polo (1254–1324) is one of the most famous examples of European visitors in premodern China. Rustichello da Pisa's Le Divisament dou monde, which narrated Marco's travels in Asia along the Silk Roads between 1271 and 1295, became a medieval bestseller across Europe.Footnote 46 The Italian Franciscan John of Pian de Carpine (d. 1252) headed an early embassy sent by Pope Innocent IV to the Great Khan.Footnote 47 Another famous Franciscan, the Fleming William of Rubruck (1215–70), arrived carrying a letter from King Louis IX of France (r. 1226–70) in Kharakorum around 1254.Footnote 48 Several friars also acquired images during their travels for their missionary work. John of Montecorvino (1246/7–c. 1289) had commissioned six pictures with biblical scenes, narrated in Latin, ‘Tartar’ (tursicus, probably Chinese or perhaps Mongolian or Turkish) and Persian.Footnote 49 William of Rubruck records that a Parisian goldsmith, Guillaume Boucher, crafted a much-admired silver tree for the court of Möngke Khan in Kharakorum which functioned as a fountain for serving alcoholic refreshments.Footnote 50 Boucher also took smaller commissions from the Roman Catholic expatriate community in Kharakorum.Footnote 51 He made a ‘beautiful silver crucifix, crafted in the French style, which had a silver image of Christ affixed upon it’, a silver pyx for the Eucharist and a pan for making communion wafers. Their loss further underscores the importance of Caterina Vilioni's tombstone as a rare tangible piece of evidence of Christian material culture from Yuan China.

The Vilioni family in Yangzhou

Although their roots have been debated in previous scholarship, the Vilioni most likely originated from Venice.Footnote 52 Another member of the family, a certain Pietro Vilioni, is recorded as a Venetian merchant who traded in central Asia. Pietro issued his last will in 1263 in the city of Tabriz (modern-day Iran), seat of the Persian Il-khanate in the Mongol empire.Footnote 53 According to his will, Pietro was the travelling partner in numerous Venetian colleganze, some of which he had contracted with his father, Vitale Vilioni.Footnote 54 Pietro imported linen to Persia from Germany, Venice, and Lombardy, as well as Stanforte cloth made in Mechlin. His profits were then reinvested in sugar and small pearls. Pietro's private possessions included a chess and backgammon board made from rock crystal, jasper, silver, gems and pearls, complemented by crystal gaming pieces, a vase, two candelabras, three bowls decorated with rock crystal, a saddle adorned with crystal, jasper, silver, gems and pearls, as well as expensive silk textiles embroidered with silver and gold thread.Footnote 55 In the second half of the thirteenth century, Venice had become a leading centre for the production of refined rock crystal objects.Footnote 56 Pietro had probably brought the crystal objects with him to Tabriz.Footnote 57 A further potential member of the family, a certain Domenico Vilioni (Ilioni), was active in Genoa in 1348. He appears in connection with the merchant Jacopo de Oliverio, who reportedly lived in China for years where he ‘quintupled his wealth’.Footnote 58 This Chinese connection has led previous scholars to identify this Domenico with Caterina's father.Footnote 59 Given that Caterina's father predeceased her and that she herself had passed away in 1342, this possibility can be ruled out.

Caterina's father probably made his living as a merchant. While we do not know his merchandise, the most likely possibilities include textiles, spices, pearls, sugar and rock crystal. These were not only traded by his kinsman Pietro Vilioni in Tabriz, but their circulation between Italy and the eastern shore of China is further attested in contemporary sources. The well-known trading manual The Practice of Commerce (Pratica della mercatura), composed by the Florentine banker Francesco Balducci Pegolotti and his associates sometime around 1339–40, names Cansay (Hangzhou) and Cambalech (Beijing) as the easternmost destinations of Italian traders.Footnote 60 Italian merchants are recorded exporting French textiles to China already by the 1330s.Footnote 61 In 1338, Toghon Temür, the last emperor of the Yuan dynasty in China, asked a group of Genoese merchants to obtain gifts for him from the west, including clearly very desirable rock crystals.Footnote 62 The burial of Caterina's brother, Antonio Vilioni, in Yangzhou in November 1344 further suggests that, like Pietro and Vitale in the Il-khanate, the Vilioni were part of a larger family enterprise with a base in Yangzhou.Footnote 63

Yangzhou's advantageous geographical position meant that the Vilioni could transport their merchandise either through overland routes or by the sea. While the Pratica describes how one could travel from Italy to China primarily by land along the Silk Roads, some evidence suggests that Genoese merchants commanded their own ships in the Indian Ocean.Footnote 64 Persia with its two key commercial centres of Ormuz (maritime port) and Tabriz (land) was a gateway where Italian merchants passed towards the Mongol empire.Footnote 65 The Genoese merchant Tommaso Gentile arrived to Ormuz in 1343, from where he originally intended to sail to China.Footnote 66 Since Pietro Vilioni was stationed in Tabriz, it is not unreasonable to propose that the city was an entrepot within a greater mercantile network which connected different members of the Vilioni family and which reached as far as Yangzhou on the shores of the East China Sea.

Yangzhou was the northernmost of the great eastern port cities of China. Functioning as an auxiliary capital of the Tang dynasty, it had served as a major port of entry to China for Arab and Persian traders since the eighth century.Footnote 67 Its importance derived from directly connecting this intercontinental commerce from the ‘Silk Road of the Sea’ through the Grand Canal to the Yuan capital, Cambalech (Beijing).Footnote 68 Yangzhou was a major economic hub that possessed a salt monopoly as well as a significant banking and commercial centre, which generated substantial revenues from the sugar, gold, tea, spice, gemstone and textile trade.Footnote 69 It was a meeting point of cultures, where people of different languages, religions and ethnicities interacted and lived together. The discovery of a trilingual imperial edict written in Chinese, Persian and Mongolian from around 1400 attests to the city's vibrant cosmopolitanism.Footnote 70

Sophisticated garden culture and ingeniously designed waterscapes were defining features of the urban core.Footnote 71 The nucleus of the municipality developed around a fortress erected alongside the Han'gou canal during the Warring States period. Direct access to waterways remained essential throughout the city's history: under the Sui dynasty (581–618) the settlement was renamed to Jiangdu, the ‘City of the River’.Footnote 72 The Grand Canal became the key waterway during the Tang dynasty, which cut through the municipal centre. During the late Southern Song period, Yangzhou was divided into three main walled districts, two military and one commercial. By 1269, at least four fortresses had been erected.Footnote 73 However, these were not sufficiently garrisoned, and the city capitulated to the Mongols without a fight in 1276. This date also signifies a commercial uplift for Yangzhou with the construction of new shipping docks. These were used to build 600 warships for Khubilai Khan's campaign against the Japanese in 1294, as well as to facilitate the expanded salt transport administration.Footnote 74 On the other hand, Yangzhou is perhaps best known for its sophisticated garden culture, which was underpinned by the wealth of the local mercantile elite.Footnote 75

In addition to numerous Buddhist temples, the Transcendent Crane Mosque in Yangzhou is one of the two earliest mosques in China.Footnote 76 This houses the cenotaph of Buhading, a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, who settled in the city in 1272. Yangzhou was also home to a lively Christian community. William of Rubruck's description of three Nestorian churches, as well as a tombstone excavated in 1981 belonging to Elizabeth, wife of Xindu from Dadu (Beijing), attests that members of the Syriac Church of the East were also present in the city in the fourteenth century.Footnote 77 This presence is further attested by the Yuan dian zhang, a collection of court decisions from between 1270 and 1322 originally written in Mongol, which reports that a certain Ao-la han, the son of the founder of an Eastern Christian church dedicated to the Cross in Yangzhou, was alive and living in the city in 1317.Footnote 78 Yangzhou was also home to a small migrant community of Roman Catholics in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The Franciscan missionary Odoric of Pordenone (1286–1331), who visited Yangzhou personally around 1324, mentioned the presence of a Franciscan convent.Footnote 79 Marco Polo's supposed three-year tenure as governor of the city has been heavily debated, but his presence in the city for several years has been generally accepted.Footnote 80 Caterina Vilioni and her family therefore must have been part of a small but well-established colony of westerners in Yangzhou, which, as Marco Polo's presence suggests, included Venetian merchants from at least the 1280s onwards. The evidence of a Franciscan convent indicates that this community not only had direct access to Roman Catholic liturgy and mass, but the right to receive proper burial in consecrated soil as well.

The visual ambiguity of Caterina's tombstone

Caterina's tombstone is formed from a single grey stone slab with a cusped top, framed by a simple vegetal pattern around the edges. While the inscription fills the lower half, the upper half is decorated with images. The top is dominated by the enthroned Virgin and Child, paired with two small angels on the left. Below this composition, three scenes form a narrative cycle of the patron saint of Caterina Vilioni, St Catherine of Alexandria, depicting her torture on the wheel, with the corpses of her two tormentors lying in the foreground; Catherine's beheading with a kneeling figure on right; and the deposition of her body by two angels into her tomb. While the subject is clearly Christian, numerous visual features are closely connected to Buddhist art. Previous scholars traced how decorated psalters and copies of Jacobus de Voragine's famous Golden Legend with illuminations of St Catherine served as prototypes for the iconography, while other features derived from local Chinese tradition.Footnote 81 This was, however, not a random amalgamation of cosmopolitan imagery. Instead, this article argues that the shape of the slab, the narrative composition and the details of the carvings reinforce the notion that the visual language of the tombstone intentionally projected cultural ambiguity.

It is first worth considering the visual context of Caterina's gravestone among burials of foreigners and members of other religious minorities in east and south-east China. The revised edition of Wenliang Wu's important corpus of religious inscriptions from Quanzhou, another major port city south of Yangzhou, collected more than 600 tombstones from the area belonging to various Islamic, Christian, Manichean, Hindu, Buddhist and local communities.Footnote 82 Comparison with this corpus shows that the form and ratio of the Vilioni tombstone is strikingly close to Muslim tombstones from the same period.Footnote 83 The slab commemorating in Arabic the death of Amir Sayyid from Bukhara in 1302 and another Chinese–Arabic bilingual stone that quotes from the Qur'an are not only analogous in shape but are similarly adorned with a decorative band running around the edges.Footnote 84 Similar Islamic tombstones were discovered in Yangzhou in the vicinity of the South Gate in the 1920s, close to the spot where the Vilioni tombstones were unearthed three decades later. For instance, the slab of a Muslim woman called ʿĀysha Khātūn (d. 724 ah/1324 ce), offers a pertinent example with a finely carved border decorated with floral and vegetal motifs (Figure 3).Footnote 85 This popular Islamic form also served as a model for Nestorian Christian funerary monuments from Quanzhou. Many of these are decorated with a pair of angels around a lotus flower, a symbol denoting purity and spiritual awakening in Buddhism, and a cross on top.Footnote 86 The same imagery appears on the tombstone of Elizabeth, who died at the age of thirty-three in Yangzhou in May 1317.Footnote 87 The trilingual inscriptions on the slab are written in Chinese, Syriac and Uighur, and use two different calendars, namely Chinese and Turkic. On the other hand, not all Nestorian grave markers bore writing: a granite stone from Quanzhou is adorned with a single yet majestic image of a crowned angel spreading his four wings above the whirling clouds on which he is seated cross-legged.Footnote 88 Besides the Vilioni siblings, the only other Roman Catholic tombstone that survives from Yuan China is that of the Franciscan friar Andrew of Perugia, who served as the third of five bishops of Quanzhou from 1323 until his death in 1332.Footnote 89 While the Latin text written with Gothic majuscules is similar to the Vilioni inscriptions, the imagery follows the Nestorian template of a lotus borne aloft by a pair of angels.Footnote 90

Figure 3. Tombstone of ‘Āysha Khātūn, 724 ah/1324. Granite. Yangzhou: Transcendent Crane Mosque. (Photo: Deborah Howard.)

The brief, although finely carved, inscription on Caterina's tombstone is not specific enough to locate its precise point of inspiration. The palaeographical evidence, namely the shape of the letters and the ligature (the typology of the letter connections), shows similarities to fourteenth-century northern Italian epigraphy.Footnote 91 Caramello and Schmitz-Esser have recently argued that the inscription was carved by an experienced Franciscan stonecutter, sent from Italy by the pope to aid John of Montecorvino.Footnote 92 However, this theory can hardly be substantiated due to a lack of evidence, especially in light of the already demonstrated presence of European lay craftsmen in Yuan China.

The scheme of the inscription is not unusual for funerary monuments across western Christendom, and in particular northern Italy.Footnote 93 For instance, the epitaph of Visconte Malaspina made in Verona in 1362 follows the same formula, only in this case a son instead of a daughter is commemorated.Footnote 94 A similar ‘hic iacet’ (here lies) formulation can be found on two fourteenth-century tombstones of Italians discovered near Ephesos.Footnote 95 Whoever drafted Caterina's inscription was thus familiar with the western European tradition. The word mileximo (thousand) may offer a further clue to the family's Venetian roots, since the use of ‘x’ for a voiceless ‘s’ is characteristic of the Venetian dialect.Footnote 96 If Caterina had died in Venice or its overseas possessions, she could have expected a very similar script and epigraph. But could this mean that the slab was made elsewhere? Elizabeth Lambourn has convincingly demonstrated that Muslim tombstones in the same period were exported along seaborne routes across the Indian Ocean littoral at great distances, from the ports of Mogadishu and Kilwa in east Africa to eastern Java.Footnote 97 The formulaic Latin inscription notwithstanding, it is clear that Caterina's tomb embarked on no such journey. The unique visual features and the shape of the slab firmly pinpoint the place of production of Caterina's tomb in Yangzhou.

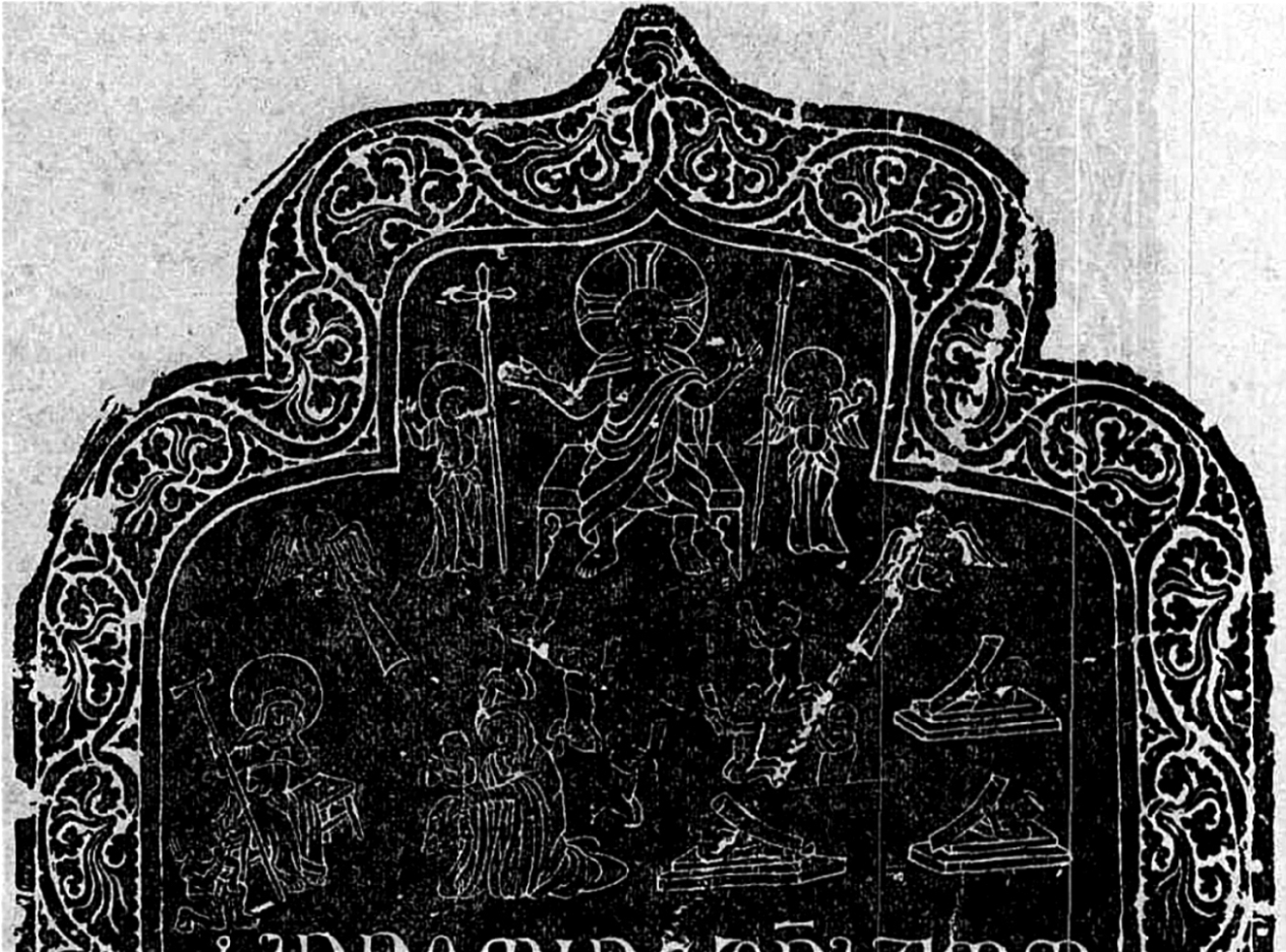

Where the Christian iconography is concerned, we can only compare Caterina's gravestone to that belonging to her brother, Antonio, from 1344 (Figure 4).Footnote 98 Above the Latin inscription, this slab depicts Christ the Judge, surrounded by two angels holding a processional cross and a lance.Footnote 99 Below, the opening of the tombs at the Last Judgment is represented on the right, while St Anthony of Egypt with a woman and a child, possibly the Virgin and Child (although without halos), appear on the left. The slab of Caterina differs from her brother's in three striking ways: it provides a narrative, it prioritises holy women (the Virgin and St Catherine), and, more specifically, it pays particular attention to a female saint associated with the ‘east’ in the medieval western imagination, St Catherine of Alexandria.

Figure 4. Antonio Vilioni's tombstone (detail), 1344. Facsimile of the rubbing of the granite tombstone. Yangzhou: Marco Polo Museum. (Image: Wikimedia Commons.)

The patron saint of Caterina was one of the most popular virgin saints and a mainstay of medieval hagiography. A convert to Christianity, she was allegedly condemned to death by the pagan Roman emperor Maxentius in the fourth century. After various attempts to torture her – including breaking her body on a wheel – were divinely frustrated, she was ultimately beheaded. According to the Greek typikon, a set of rules composed by abbot Symeon of Sinai in 1214, her body was deposited by angels in the monastery on Mount Sinai.Footnote 100 The abbreviated cycle on Caterina Vilioni's tombstone composed of three images of Catherine's torture, decapitation and burial follow the iconographical tradition already established in the western canon. The late thirteenth-century vita icon in the Museo Nazionale in Pisa and the Getty Museum's altarpiece by Donato and Gregorio d'Arezzo from around 1330 (Figure 5) both include these three scenes, among others.Footnote 101 In both cases, the scenes are shown separately. In contrast, Caterina's tombstone presents the narrative in a continuous manner. This fluidity, as well as the distinctly linear carving style, are features shared with Buddhist art in the Yuan period, exemplified by the 1340s prints of The Lotus Sūtra (Miaofa lianhua jing) from Quanzhou.Footnote 102 On the other hand, small-scale artworks from western Europe starting from the 1340s also developed a tendency that favoured the reduction and compression of the visual programme, which draws further attention to the ambiguity of the free-flowing yet compact narrative of the Vilioni slab. A petite ivory diptych with a Saint Catherine cycle (c. 1350) condenses the beheading and the transfer of the body into a single scene, placed above the torture on the wheel.Footnote 103 This object serves as an especially close analogy to the tomb's abbreviated narrative. It is indeed possible that a small and highly mobile object of private devotion was used as a potential model for the gravestone's imagery.

Figure 5. Donato and Gregorio d'Arezzo, St Catherine and scenes from her life, c. 1330. Tempera and gold leaf on panel, 107 × 174 cm. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 73.PB.69. (Photo: The J. Paul Getty Museum.)

While they together act out a Christian narrative, the half-naked kneeling figure of St Catherine, the exotic clothing of the executioner and the kneeling man wearing a loose robe at the edge of the execution scene each diverge from western iconography in highly revealing ways. First of all, the kneeling figure has been identified by Rouleau and Arnold as a Franciscan friar, and, most recently, by Caramello and Schmitz-Esser as Domenico Vilioni, ‘the father and commissioner of the work, holding the deceased child in his hand’.Footnote 104 Since Domenico is mentioned as quondam or deceased in the inscription, the latter possibility can be excluded. Moreover, his clean-shaven head and the voluptuous folds of his tunic resemble a Buddhist monk more closely than a Franciscan friar, whose habit would have been cinctured with a cord.Footnote 105 The occasional inclusion of Buddhist monks in the wall paintings of Yuan tombs reinforces this argument. On the west wall of an octagonal tomb chamber from 1309 at Hongyucun in Shanxi, a deceased couple is depicted (Figure 6).Footnote 106 While the husband looks at their three sons, the wife's gaze is directed towards a Buddhist monk. Therefore, regardless of who the kneeling figure was meant to represent on Caterina's tombstone, his portrayal in the guise of a Buddhist monk immediately forged a visual connection with Yuan funerary art.

Figure 6. Tomb mural with deceased couple flanked by their three sons and a Buddhist monk and his attendant, 1309. Mural. Tomb at Hongyucun, Xing county, Shanxi province. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons.)

Secondly, despite St Catherine generally being depicted fully clothed in western images, she is visualised semi-naked during her martyrdom on the gravestone. Comparable figures, however, appear in woodblock prints, such as the one representing the execution Dou E in a Yuan play written by Guan Hanqing (c. 1210–c. 1298).Footnote 107 Shane McCausland fittingly argued that the unclothed back of Dou E recalls Buddhist judgment scenes, where the punishment is carried out on similar semi-nude bodies.Footnote 108 The silk painting by Lu Zhongyuan (active c. 1271–1368) envisions the torture of men and women, clad in loincloths, on the orders of one of the Ten Kings of Hell.Footnote 109 The disrobed figure of St Catherine awaiting execution on the Yangzhou slab thus probably reflected this firm association between the disrobed body and punitive mutilation in Yuan visual culture.

In contrast to these tormented characters, however, St Catherine wears a crown. This attribute is not uncommon in western iconography, as demonstrated by the ivory diptych discussed above. However, in contrast to the latter western exemplar, the Yangzhou tombstone showcases a headpiece that recalls the shape of Buddhist tiaras, like the one on a late Yuan porcelain of the head of a bodhisattva in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.Footnote 110

Finally, the belted tunic of the executioner, paired with a wide-rimmed wind hat and tall boots, identify him as a contemporary Mongol soldier. Similarly fashionable figures appear in a silk painting depicting the hunt of Khubilai Khan from around 1280, attributed to the Chinese court artist Liu Guandao (1258–1333).Footnote 111 Shifting the attention from court painting to more widely accessible works, comparable figures are often featured in woodblock prints accompanying fourteenth-century pingua or popular novels. The historical fiction The Plain Tale of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi pinghua), printed in 1321–3, includes numerous scenes populated with such soldiers (Figure 7).Footnote 112 Various figures in the encyclopaedia Shilin Guanji, printed in the 1330s, also offer analogies.Footnote 113

Figure 7. Soldiers dressed in Mongol fashion, The Plain Tale of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi pinghua) composed in the Song and Yuan, printed in 1321–3. (Tokyo: National Diet Library. Photo: National Diet Library.)

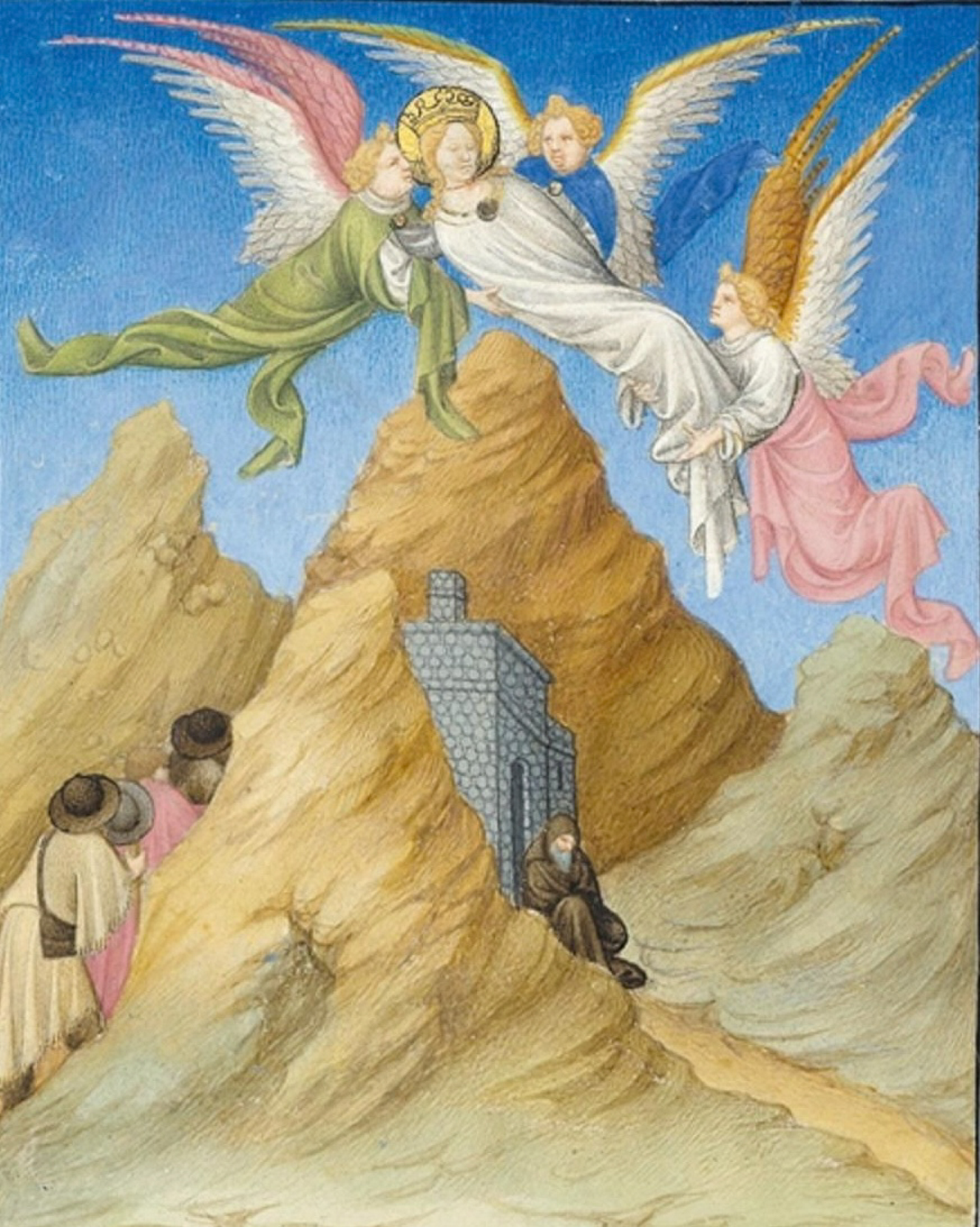

Other features, however, are less decisively identified. The layered yet shallow tomb of St Catherine is not unlike the one depicted in the d'Arezzo altarpiece. However, this form is also close to Muslim tombs from the Yuan dynasty, such as the multi-layer cenotaph of Buhading in Yangzhou (Figure 8).Footnote 114 Moreover, the angels are represented in a manner similar to late medieval European examples such as the illumination of the Belles Heures of duc de Berry (Figure 9).Footnote 115 In both cases, the legs of the angels are covered by their robes. Yet similar figures also appear in Chinese art, such as the winged creatures on the murals from the sixth century in the Dunhuang caves, namely Mogao Cave 285 (Figure 10).Footnote 116

Figure 8. Tomb of Buhading, 1275. Granite. Yangzhou: Transcendent Crane Mosque. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons.)

Figure 9. Angels transporting St Catherine's body, The Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry, 1405–1408/1409. Tempera, gold, and ink on vellum, 23.8 × 17 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 54.1.1a, b, fo. 20r. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Open Access.)

Figure 10. Flying apsara, 535–57. Mural. Dunhuang: Mogao Cave 285. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons.)

The top of Caterina's tombstone is occupied by one of the most central images of Christianity, the enthroned Virgin and Child. The frontal side of a roughly contemporary red marble sarcophagus that bears the arms of the Sanguinacci family, probably originating from the Veneto around 1300, is decorated with a similar image (Figure 11).Footnote 117 However, in contrast to the robust throne of the Italian Madonna, on the Yangzhou tombstone Mary is sitting on a squat little chair similar to stools common in contemporary China.Footnote 118 Moreover, the haloed figure of the Virgin Mary is remarkably similar to Guanyin (觀音).Footnote 119 Originally a male figure in the Buddhist pantheon, this bodhisattva became a popular female deity in thirteenth-century China as the child-giving (songzi) Guanyin. She sometimes appears with a child on her lap, and her head is often framed by the moon in a manner that is strikingly reminiscent of the Virgin Mary's halo (Figure 12).

Figure 11. Sarcophagus with Virgin and Child and the arms of the Sanguinacci Family, c. 1300. Red limestone, 82.6 × 223.5 × 94 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 18.109. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Figure 12. Zhang Yuehu, Guanyin, late 1200s. Hanging scroll, ink on paper, 104 × 42.3 cm. Cleveland: The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1972.160. (Photo: The Cleveland Museum of Art.)

The cross, a central symbol of Christianity, appears three times on the Vilioni slab, integrated in the imagery as well as the text. The Christ Child's halo is inscribed with it, and it frames the inscription both at the beginning and at the end. Besides the previously mentioned Xi'an stele and Luoyang pillar, the cross is the most common feature of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century eastern Christian tombstones from Quanzhou and elsewhere. The symbol, however, was also not limited to monumental art nor funerary sculpture. Hundreds of small, flat bronze plaques survive from northern China from the Yuan dynasty, which are usually termed as the ‘Ordos Crosses’ as well as ‘Nestorian Crosses’.Footnote 120 The loop on their back indicates that they were attached to clothing or worn on the body. Scholars have proposed that they served talismanic, apotropaic purposes.Footnote 121 The occasional traces of red ink, combined with the purposeful abstention from repetition of the visual features, however, suggest that they were more likely used as seal matrices, in which case the unique design of each piece was for security purposes.Footnote 122 In either case, the crosses’ direct association with Christians is uncertain. Most feature a Syrian or Maltese cross as their central theme, but this is combined with Buddhist symbols, animal motifs (especially birds) and various geometric patterns.Footnote 123 For instance, an exemplar from the Royal Ontario Museum resembles a swastika, a common motif which represents light rays and good fortune in Buddhist art (Figure 13).Footnote 124 The Ordos Crosses thus project a similar meshing of Christian and Buddhist designs to that of the Vilioni slab. Moreover, they highlight that the shape of the cross was present across a broad spectrum of Yuan material culture, which was not necessarily limited to a strictly Christian context.

Figure 13. Ordos Crosses, tenth–fourteenth centuries. Cast bronze. Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, Bishop William C. White Collection. (Photo: author.)

No surviving written sources document Caterina Vilioni's life, nor does the taciturn funerary inscription reveal her age, marital status, or whether she was born at or migrated to Yangzhou. Yet, the tombstone itself offers invaluable evidence to understand better her complicated identity. The ambiguous features we have explored highlight the presence of a variety of visual echoes in the imagery of Caterina's gravestone. The shape, composition and details of the imagery of the tombstone functioned in combination to communicate intentionally ambiguous messages associated with Buddhist, Christian and even Islamic traditions to a diverse audience. The heterogeneous visual language of Caterina's funerary monument therefore exhibits a sort of cultural mixing which some scholars would characterise as ‘hybridity’.Footnote 125 This frequently employed framework for cross-cultural art historical analysis, which prioritises the syncretic aggregation of discrete cultural forms, however, fails to elucidate fully the complex social and cultural processes of displacement behind this object's creation. Instead of arguing through a binary system of influence and reception, acknowledging the porous nature of cross-cultural artefacts is key. By drawing on ‘cultural ambiguity’ as a more useful category of analysis, my approach shifts the emphasis from the geographic points of origins to an appreciation of the mobility of these multicultural features as well as the process of their displacement.Footnote 126

While Caterina's tombstone communicated different messages to different audiences, the ambiguity of the visual language also consistently signalled a certain sense of displacement. Its meaning was never fixed, nor was it a question of either–or. For a Muslim merchant trading in Yangzhou, the shape and ornamental patterns would have seemed familiar from Islamic funerary monuments, while the imagery and inscription appeared entirely foreign. A fourteenth-century Buddhist would have recognised the figures and objects represented in the St Catherine narrative but would have found their religious significance incomprehensible. As for Christian observers, a convert from Yangzhou, a member of the Church of the East and a European visitor would have all perceived the imagery through very different lenses.

Even if the viewer would not have been able to locate the parent cultures of the extraneous features, they would have certainly recognised their evident displacement. In this sense, the Yangzhou tombstone prompts art-historical scholarship to engage in more nuanced ways with similar objects in the vast ‘grey area’ that lies between exotic and exoticizing objects.Footnote 127 Instead of perpetuating the preoccupation with sources of origins, the peripatetic visual repertoire of Caterina's tombstone thus highlights the importance of recognising not only the outcomes but also the processes of cultural translation and artistic displacement as effective vectors of interpretation on their own.

Otherworldly passport

So far we have seen that displacement played an important part in formulating the visual language of the funerary monument. Continuing on this path, this section will explore the role of the tombstone as a physical marker which signalled Caterina's migration between this life and the next.

The cusped shape of Caterina's tomb and the combination of inscriptions on the lower half with images on the upper half offer a template analogous to a contemporary Mongolian passport or paiza (Figure 14).Footnote 128 The name derives from a Persian reading of the Chinese paizi (tablet) which refers to the format of these passes. Sources written in the Mongolian language mention them as gerege meaning ‘that which bears witness’, and they were traditionally carried in tandem with a decree that explained the reasons behind the privileges the paiza conferred.Footnote 129 As tablets of authority, the paizas were issued by the Khan and they allowed envoys, diplomats, office holders and foreign travellers to pass across borders easily. They could also empower their bearers to requisition resources. Baohai Dang has divided paizas into four basic categories: postal-road tablets, passes for officers (e.g. commanders and diplomats), night travel/patrol and lucky charm.Footnote 130 Higher-level paizas were typically made of metal, most often iron, although the ones crafted for more elite owners were sometimes moulded from or inlayed with silver and gold. For instance, the four tablets that Marco Polo, his father and his uncle received from Gaigatu, Il-Khan of Persia (r. 1291–5) were made of gold.Footnote 131 The Beijing-born diplomat and monk Rabban Bar Ṣawma also received a similar paiza when Arghun Khan dispatched him as the leader of an Il-khanid embassy to western Europe in 1286.Footnote 132

Figure 14. Paiza (Mongol safe conduct pass), late thirteenth century. Iron with silver inlay, 18.1 × 11.4 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993.256. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Another extant paiza issued by Abdullah Khan of the Golden Horde (r. 1362–70) is an oblong silver tablet.Footnote 133 Paizas made in the Yuan period were instead typically cast in a pear-shape format, called in Chinese yuanfu or round tallies.Footnote 134 An exemplar in the National Museum of Mongolia in Ulaanbaatar authorised its holder to go about at night.Footnote 135 In addition to the multilingual inscriptions, a serial number in Chinese (‘Di 50’) was also implemented, which functioned as a security device to limit the circulation of these sought-after passes.Footnote 136 In an analogous attempt in the Il-Khanate, Ghazan Khan (r. 1295–1304) cancelled all old paizas and issued new ones, which contained the names of their bearers and were to be returned at the end of service.Footnote 137 These passes thus also signalled the status and the identity of their owners.

The hooks or holes on top enabled the travellers to wear the paiza as a pendant or to fix it onto their clothing. They were inscribed with instructions to permit safe passage to their carriers. The ’Phags-pa script of a late thirteenth-century silver-inlayed iron paiza from China recalls the following warning: ‘By the strength of Eternal Heaven, an edict of the Emperor [Khan]. He who has not respect shall be guilty’ (Figure 14).Footnote 138 Enhanced with an animalistic mask on the top, similar to the decoration of Tibetan mirrors for reflecting evil, this paiza also provided protection on a spiritual level.Footnote 139 This apotropaic function might explain why a Yuan talisman was crafted in the form of a tiger-head paiza.Footnote 140 The Vilioni tombstone acted in an analogous vein by heralding the identity of its owner through the inscription, while invoking the help of Caterina's two heavenly protectors through the imagery. Therefore, in similar way to a paiza in the earthly realm of the Mongol empire, the tombstone signalled the hope of safe passage to the otherworld.

The images on Caterina Vilioni's tombstone also evoke associations with two different physical locations, both in the vicinity of Egypt. The first one is Sinai, where the angels allegedly transported the body of St Catherine after her decapitation. The Eastern Orthodox monastery on Mount Sinai had been built in the sixth century on the site where God spoke to Moses from the Burning Bush.Footnote 141 As Nancy P. Ševčenko demonstrated, its connection to St Catherine appears in the written sources first in Rouen in France, and even there relatively late, only in the eleventh century, although it subsequently spread rapidly.Footnote 142 Due to the enormous popularity of St Catherine in western Europe, Sinai became a major pilgrimage destination for Latin pilgrims in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. While after the Council of Florence in 1438–9 and the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 the monastery became less hospitable for western travellers, the creation of Caterina Vilioni's tombstone falls precisely in the peak period of Latin pilgrimage to St Catherine's remains on Sinai. Therefore, this image recalled an important locus sanctus of western Christianity and ushered the attention to the parallel between the actual grave of Caterina Vilioni in Yangzhou and the sepulchre of her holy patron, St Catherine of Alexandria in the Sinai.

On the other hand, the scenes from the martyrdom of St Catherine are set in the ancient city of Alexandria. A gateway to the east, this place had special importance for Venetian merchants from both an economic and a symbolic point of view. Although the main commercial centre of the Mamluk empire was Cairo, its chief Mediterranean port was Alexandria.Footnote 143 Due to the unstable and aggressive interactions between the Christian and Islamic worlds during the crusades, direct access to the much sought-after eastern merchandise deposited in the main warehouses in Cairo was intentionally prohibited.Footnote 144 Instead, European merchants from the dār al-ḥarb (Land of War) were limited to conducting their trade in Alexandria and Damietta alone. Moreover, Alexandria also became a crucial point of reference in the sacred geography of the Venetian empire. St Mark, the apostle and first bishop of Alexandria, became the patron saint of Venice. This relationship was codified by a furtum sacrum in 828–9, when two Venetian merchants, Bruno di Malamocco and Rustico di Torcello, smuggled out his bodily remains from Alexandria and transferred them to Venice. Deborah Howard and Thomas Dale have drawn attention to the ongoing Venetian efforts to promote this sacred connection between Venice and Alexandria.Footnote 145 For instance, in a mosaic of the atrium of San Marco, the burial of St Mark in Alexandria appears as if it were happening under the thirteenth-century verde antico ciborium in the apse of the basilica di San Marco itself.Footnote 146 The promotion of Venice as a ‘new Alexandria’ in turn also helped to emphasise and in a way justify the rapidly expanding mercantile empire of Venice in the broader Mediterranean. Thus, the reference to Alexandria on Caterina's tombstone could also communicate the link between the Vilioni family and its ancestral homeland, Venice.

Yet, Caterina's tombstone not only referenced spiritual travel, but also attested to the increased patterns of crossing geographical boundaries in a more mundane sense. One might recognise two final themes which Yuan paizas and Caterina's ‘otherworldy passport’ share: mobility and a sense of foreignness. Firstly, both can be perceived as tangible mementos of mobility. The most basic type of paiza was used for accessing the jam, the impressive post-road system of the Mongol empire, which under Khubilai Khan constituted more than 1,400 jam stations, serviced by 44,293 horses and other pack animals.Footnote 147 Given the burden of its upkeep, the system was already crumbling by the early fourteenth century.Footnote 148 Yet, the jam still facilitated travel during the lifetime of Caterina Vilioni, and the post-road duty survived in Tibet and Mongolia as late as the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 149 The postal tablets authorised the requisition of fresh horses, escorts, as well as room and board. Although the serial numbers suggest that the Yuan government issued such travel paizas by the thousands, only four are extant.Footnote 150 These exemplars are thus invaluable testimonies of the material legacy of this once extensive post-road network. In an analogous vein, Caterina's gravestone, erected in Yangzhou some 8,700 kilometres away from Venice, underscores the existence of global trade and social networks that bridged vast distances already in the medieval period. Although the precise paths through which her family reached Yangzhou cannot be charted, the fact that this voyage took place matters. Thus, Caterina's tomb, similarly to a paiza, acts as another tangible token of mobility.

Furthermore, Caterina's Latin tombstone is inscribed with a foreign script, much like surviving paizas. Since passports were used to assist travel and border-crossing, they were often labelled in multiple languages. The tablets made in the Yuan all included ’Phags-pa, developed from Tibetan-Indic letters, which Khubilai Khan proclaimed as the official script of the Mongol empire in 1269.Footnote 151 On the Ulaanbaator paiza, ’Phags-pa was paired with Chinese, Arabic-Persian and Uighur.Footnote 152 The record, however, is set by another round Yuan paiza, recovered from Ke'er’qin Youyi Zhongqi in Inner Mongolia.Footnote 153 This is labelled with no less than five different scripts: ’Phags-pa Mongolian, Uighur Mongolian, Tibetan, Arabic-Persian and Chinese.

In 1962, a round Yuan paiza was unearthed in Yangzhou.Footnote 154 The metal tablet, which permitted its user to travel at night, was engraved in Chinese on one side, while bearing a double inscription in ’Phags-pa (left) and Arabic-Persian (right) on the reverse. The Chinese text reveals that it was issued by the military and regional administrative office of the Pacification Commission and Chief Military Command.Footnote 155 This dates the paiza to a brief interval, since the office was established in 1355 and the wall in which the tablet was discovered was erected in 1357.Footnote 156

The Yangzhou paiza, made in the decade following the death of Caterina Vilioni in 1342, was incorporated in the same section of the base of the western city wall by the now-demolished South Gate as Caterina's tombstone.Footnote 157 A number of Islamic tombstones inscribed in Arabic were already excavated in the surroundings of the South Gate during the 1920s.Footnote 158 The fact that many of these slabs were relatively recently carved, including Caterina's only a few years earlier, suggests that there was an effort to uproot foreigners’ tombstones and eliminate them from plain sight in the city. Moreover, while lithic spolia have been often reused in wall constructions in the period, it is telling that a metal paiza was also thrown into the same ditch, through which it stored various mismatched objects inscribed with foreign scripts. That the mid-fourteenth-century residents of Yangzhou decided to get rid of these objects together underscores the relevance of considering the paizas and Caterina's ‘otherworldly passport’ in tandem. Yet it is also worth remarking that these objects, which were meant to facilitate the crossing of boundaries – whether for night travel on the road or the voyage between this life and the next – were both subsumed into the city walls by the South Gate of Yangzhou to form part of a threshold themselves.

Conclusions

The primary objective of this study was to examine the crossing of boundaries, not only through the geographical, social, linguistic and religious distance between trecento Italy and the Yuan realm, but also through the immaterial transition from this life to the next which the funerary marker literally set in stone. The notarial documentation of mercantile activities, the written memoirs of friars and missionaries and the surviving diplomatic correspondence have allowed historians to chart the movement of men across great distances and widely different societies between Europe and Asia. The narrative that emerges from these sources is one of dynamic and powerful voyagers, who embarked on dangerous trips fuelled by the pursuit of spiritual wealth or material riches. This, however, is only an incomplete account, from which women, children and families have so far been nearly entirely exempt. Shifting the attention from the living to the dead, however, can cast light on these previously marginalised segments of society. Caterina Vilioni's gravestone attests not simply to the presence of a European Christian woman in premodern China, but a close examination of its inscription and imagery revealed a great deal about her complex identity with ties both to the local cosmopolitan setting in Yangzhou and also to her ancestral homeland in Venice.

In exploring the intertwined visual language and the multicultural geopolitical context of Caterina's tombstone, a key goal was to shed light on the dynamic processes behind how cultural and religious barriers were negotiated in premodern Eurasia. This article recontextualised Caterina Vilioni and her gravestone through three focal points. Firstly, it investigated the origins of the Vilioni family and explored the magnitude of Sino-Italian mercantile interactions. While there have been uncertainties regarding the Vilioni, the surviving evidence suggests that the family stems from Venice. Despite trade along the Silk Roads still being primarily modelled on indirect exchange conducted through chains of middlemen, the case study of the Vilioni suggests the possibility of direct trade between China and Italy either by land or by sea, coordinated by extensive family enterprises. Furthermore, the expensive chess and backgammon set listed in Pietro Vilioni's will from Tabriz shows that merchants also travelled with more personal objects. The hagiographical narrative of Caterina's gravestone strengthens this interpretation by drawing attention to the likely transmission of small-scale devotional artefacts between Italy and China, such as illuminated manuscripts and ivory diptychs. Secondly, instead of attempting to locate the inspiration for certain features of the imagery of the tombstone in either Buddhist or Christian art, this article suggested that the visual language intentionally communicated cultural ambiguity. The form of the gravestone, the fluidity of the narrative and the specific visual features of the composition were not a random amalgamation of the cosmopolitan context of the commission. Instead, by recognising that the cultural and religious context of the tomb was purposefully left ambiguous, we can better comprehend why this multivalent imagery was especially suitable to project the polymorphic identity of Caterina Vilioni as a ‘stranger’, as well as a settled immigrant in Yangzhou. This offers an opportunity to move beyond the more traditional models of investigating the mere intelligibility of objects stemming from cross-cultural heritage, and to push the investigation towards in-depth questions of the role of artistic patronage in presenting the complicated identity of uprooted Europeans as strangers in the Mongol empire. A western traveller, an Islamic merchant and a native resident from Yangzhou would have each perceived some details as familiar and some as distinctly out of place, regardless of whether they were able to chart the source of origin for the latter. Through displacement, mobility thus functions as an added value on its own in the slab's imagery, and a useful interpretative vector. Finally, by comparing it to Mongol paiza, this article has proposed that Caterina's tombstone functioned as an ‘otherworldly passport’, which invoked spiritual protection and promised safe passage between two realms. This enquiry highlighted how the visual programme of the tomb evoked two locales: Sinai as a key locus sanctus of western Christianity in the era, and Alexandria, which was important for the Vilionis’ homeland, Venice, for both commercial and symbolic reasons. As the example of the Polo family shows, the paiza were prized possessions and were even recorded in their owners’ last wills. Instead of being melted down for their precious metal, the paizas were kept as souvenirs, being not only tangible mementos of their owner's time spent in the Mongol empire, but also badges of identity and personal standing. Made from stone, another extremely resilient material, and in a way echoing strikingly similar messages, Caterina Vilioni's tombstone ultimately offers invaluable tangible evidence that helps us to shed more light on the creation and promotion of the identity of a European Christian woman in the Yuan realm, even when the written sources are silent.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Deborah Howard and Craig Clunas for reading drafts of this article. I am also grateful to the editor Jan Machielsen and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.