Introduction

Despite continuing actions put to achieve social recognition and legal rights, in many areas of the world, sexual minorities are still highly exposed to traumatization (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, 2015). A growing body of evidence underlined that the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer people (LGBTQ) are more exposed to traumatic events in life, including hate crimes, intimate partner violence and sexual assaults (Mongelli et al., Reference Mongelli, Perrone, Balducci, Sacchetti, Ferrari, Mattei and Galeazzi2019; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Austin, Corliss, Vandermorris and Koenen2010; Seelman et al., Reference Seelman, Woodford and Nicolazzo2017; Trombetta and Rollè, Reference Trombetta and Rollè2022; Walters et al., Reference Walters, Chen and Breiding2013). Also, a higher prevalence of childhood abuse was found among sexual minority children, which accounted for up to half of mental health disparities by sexual orientation, especially for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Rosario, Corliss, Koenen and Austin2012). According to the diagnostic criteria, PTSD is developed in response to events that overpower the adaptative ability of the person, and the listed traumatic experiences entail being directly exposed to death, threatened death or severe personal damage, including physical or sexual assault (Long et al., Reference Long, Elhai, Schweinle, Gray, Grubaugh and Frueh2008). The core clinical features of PTSD are that people tend to re-experience the traumatic event intrusively, with detrimental consequences on personal functioning and high psychological suffering (Pai et al., Reference Pai, Suris and North2017; Sareen, Reference Sareen2014). In addition, PTSD revealed as a multidimensional disorder, with different neurobiological underpinnings, including alterations of the sympathetic nervous system (De Berardis et al., Reference De Berardis, Marini, Serroni, Iasevoli, Tomasetti, de Bartolomeis, Mazza, Tempesta, Valchera, Fornaro, Pompili, Sepede, Vellante, Orsolini, Martinotti and Di Giannantonio2015, Reference De Berardis, Vellante, Fornaro, Anastasia, Olivieri, Rapini, Serroni, Orsolini, Valchera, Carano, Tomasetti, Varasano, Pressanti, Bustini, Pompili, Serafini, Perna, Martinotti and Di Giannantonio2020). Over the years, the literature identified as traumatic also less intense situations, but for which the traumatic potential consists in the systematic repetition of the experience, such as being persecuted and discriminated against, especially for invariable personal characteristics such as race, religious beliefs, gender and sexual orientation (Alessi et al., Reference Alessi, Meyer and Martin2013; Auxéméry, Reference Auxéméry2018; Keating and Muller, Reference Keating and Muller2020; Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Lynch, Hinds, Gatsby, DuVall and Shipherd2022; Solomon et al., Reference Solomon, Combs, Allen, Roles, DiCarlo, Reed and Klaver2021). The Minority Stress Model proposed by Meyer (Reference Meyer2003), provides a theoretical framework for understanding the ways in which repeated traumas can lead to an increased prevalence of mental disorders among sexual minorities. Research showed that sexual minorities’ minority stress can lead to emotional dysregulation, social and interpersonal conflicts and negative cognition that can mediate the association with poor mental health outcomes (Hatzenbuehler, Reference Hatzenbuehler2009; Marchi et al., Reference Marchi, Arcolin, Fiore, Travascio, Uberti, Amaddeo, Converti, Fiorillo, Mirandola, Pinna, Ventriglio and Galeazzi2022a; Mongelli et al., Reference Mongelli, Perrone, Balducci, Sacchetti, Ferrari, Mattei and Galeazzi2019). Moreover, internalized homophobia has been shown to predict PTSD symptom severity in sexual minorities with a history of trauma (Gold et al., Reference Gold, Feinstein, Skidmore and Marx2011). LGBTQ groups are also at increased risk of suicidal behaviours, and that has been hypothesized to be a consequence of the experience of repeated discrimination (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Lynch, Hinds, Gatsby, DuVall and Shipherd2022; Marchi et al., Reference Marchi, Arcolin, Fiore, Travascio, Uberti, Amaddeo, Converti, Fiorillo, Mirandola, Pinna, Ventriglio and Galeazzi2022a). Therefore, recognizing and addressing PTSD may have an impact on psychopathology translationally.

Our study aimed to explore the risk of PTSD in the LGBTQ population compared with non-LGBTQ individuals, independent of the type or intensity of the trauma to which individuals may have been exposed. The secondary goal was to detail the risk of PTSD among different subgroups such as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer individuals, compared with cisgender heterosexual ones.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald, McGuinness, Stewart, Thomas, Tricco, Welch, Whiting and Moher2021). The protocol of this study was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022354616).

Data sources and search strategy

We searched the PubMed (Medline), Scopus, PsycINFO and EMBASE databases until September 30, 2022, using the strategy outlined in the Supplementary Table S1 of the Appendix. With the aim to maximize the number of studies included, no restrictions regarding the language of publication or publication date were set.

Eligibility criteria

We included observational studies reporting a comparative estimation of rate of PTSD among the LGBTQ population vs. the general population (i.e., heterosexual cisgender—controls), without any restriction on participants’ age or setting of the enrolment.

We excluded reviews, case reports, case series and studies that did not report data for the measurements of the outcome in the targeted population. We only included studies published in peer-reviewed journals, excluding conference abstracts and dissertations. If data from the same sample were published in multiple works, we considered only that study reporting more exhaustive information. Sample overlap was ruled out through a careful check of the registration codes as well as the place and year(s) of sampling.

Terms and definitions

LGBTQ status was defined as self-reported. PTSD diagnosis had to be defined according to standard operational diagnostic criteria (i.e., according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM] (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) or the International Classification of Diseases [ICD] (World Health Organization, 2018)). We also included studies where PTSD diagnosis was made according to the score on validated psychometric tools, operationalized to ICD or DSM definition.

Data collection and extraction

Four authors (MM, DU, EDM and AT) preliminarily reviewed titles and abstracts of retrieved articles. The initial screening was followed by the analysis of full texts to check compliance with inclusion/exclusion criteria. A standardized form was used for data extraction. Information concerning the year of publication, country, setting, name of the study/cohort, characteristics of study participants (sample size, age, percentages of men and women), LGBTQ status and PTSD rates among the LGBTQ groups and the controls were collected by two authors (MM and PG) independently. Extraction sheets for each study were cross-checked for consistency, and any disagreement was resolved by discussion within the research group.

Statistical analyses

The meta-analysis was performed by comparing PTSD rates between controls vs. overall LGBTQ people and controls vs. each LGBTQ subgroup. Pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were generated using inverse variance models with random effects (DerSimonian and Laird, Reference DerSimonian and Laird1986). The results were summarized using forest plots. Standard Q tests and the I 2 statistic (i.e., the percentage of variability in prevalence estimates attributable to heterogeneity rather than sampling error or chance, with values of I 2 ≥ 75% indicating high heterogeneity) were used to assess between-study heterogeneity (Higgins and Thompson, Reference Higgins and Thompson2002). Leave-one-out analysis and meta-regression were performed to examine sources of between-study heterogeneity.

If the meta-analysis included more than 10 studies (Sterne et al., Reference Sterne, Sutton, Ioannidis, Terrin, Jones, Lau, Carpenter, Rücker, Harbord, Schmid, Tetzlaff, Deeks, Peters, Macaskill, Schwarzer, Duval, Altman, Moher and Higgins2011), funnel plot analysis and the Egger test were performed to test for publication bias. The Egger test quantifies bias captured in the funnel plot analysis using the value of effect sizes and their precision (i.e., the standard errors) and assumes that the quality of study conduct is independent of study size. If analyses showed a significant risk of publication bias, the ‘trim and fill’ method was employed to estimate the number of missing studies and the adjusted effect size (Duval and Tweedie, Reference Duval and Tweedie2000; Sterne et al., Reference Sterne, Egger and Moher2008; Sutton, Reference Sutton2000; Terrin et al., Reference Terrin, Schmid, Lau and Olkin2003). All the analyses were performed in R (RStudio Team, 2021) using meta and metafor packages (Balduzzi et al., Reference Balduzzi, Rücker and Schwarzer2019; Viechtbauer, Reference Viechtbauer2010). Statistical tests were two-sided and used a significance threshold of p-value < 0.05.

Risk of bias assessment and the GRADE

Bias risk in the included studies was independently assessed by five reviewers (AT, DU, EDM, PG and EA), using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Altman, Gøtzsche, Jüni, Moher, Oxman, Savović, Schulz, Weeks and Sterne2011). Each item on the risk of bias assessment was scored as high, low or unclear, and the GRADE tool was used to assess the overall certainty of evidence (Schünemann et al., Reference Schünemann, Brożek, Guyatt and Oxman2013). Further information is available in the Supplementary Appendix.

Results

Study characteristics

Figure 1 summarizes the paper selection process: from 654 records screened on title and abstract, 126 full texts were analysed. The review process led to the selection of 27 studies (Alba et al., Reference Alba, Lyons, Waling, Minichiello, Hughes, Barrett, Fredriksen-Goldsen, Edmonds, Savage, Pepping and Blanchard2022; Bettis et al., Reference Bettis, Thompson, Burke, Nesi, Kudinova, Hunt, Liu and Wolff2020; Brewerton et al., Reference Brewerton, Suro, Gavidia and Perlman2022; Brown and Jones, Reference Brown and Jones2016; Burns et al., Reference Burns, Ryan, Garofalo, Newcomb and Mustanski2015; Caceres et al., Reference Caceres, Veldhuis, Hickey and Hughes2019; Carey et al., Reference Carey, Leard-Mann, Lehavot, Jacobson, Kolaja, Stander and Rull2022; Evans-Polce et al., Reference Evans-Polce, Kcomt, Veliz, Boyd and McCabe2020; Flentje et al., Reference Flentje, Leon, Carrico, Zheng and Dilley2016; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Beld, Khoddam-Khorasani, Flentje, Kersey, Mousseau, Frank, Leonard, Kevany and Dawson-Rose2021; Harper et al., Reference Harper, Crawford, Lewis, Mwochi, Johnson, Okoth, Jadwin-Cakmak, Onyango, Kumar and Wilson2021; Hatzenbuehler et al., Reference Hatzenbuehler, Keyes and Hasin2009; Holloway et al., Reference Holloway, Green, Pickering, Wu, Tzen, Goldbach and Castro2021; Jeffery et al., Reference Jeffery, Beymer, Mattiko and Shell2021; Lehavot and Simpson, Reference Lehavot and Simpson2014; Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Lynch, Hinds, Gatsby, DuVall and Shipherd2022; Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Goldbach, Mamey, Kintzle and Castro2018; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Ganulin, Dretsch, Taylor and Cabrera2020; Mustanski et al., Reference Mustanski, Garofalo and Emerson2010; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Rosario, Corliss, Koenen and Austin2012; Rodriguez-Seijas et al., Reference Rodriguez-Seijas, Eaton and Pachankis2019; Schefter et al., Reference Schefter, Thomaier, Jewett, Brown, Stenzel, Blaes, Teoh and Vogel2022; Terra et al., Reference Terra, Schafer, Pan, Costa, Caye, Gadelha, Miguel, Bressan, Rohde and Salum2022; Walukevich-Dienst et al., Reference Walukevich-Dienst, Dylanne Twitty and Buckner2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, McAvay, Warren, Miller, Pho, Blosnich, Brandt and Goulet2021; Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Garvert and Cloitre2015; Whitbeck et al., Reference Whitbeck, Chen, Hoyt, Tyler and Johnson2004), referring to 27 different samples, leading to a total of 273,842 controls (i.e., heterosexual or cisgender) and 31,903 LGBTQ people, which were included in the quantitative synthesis.

Figure 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

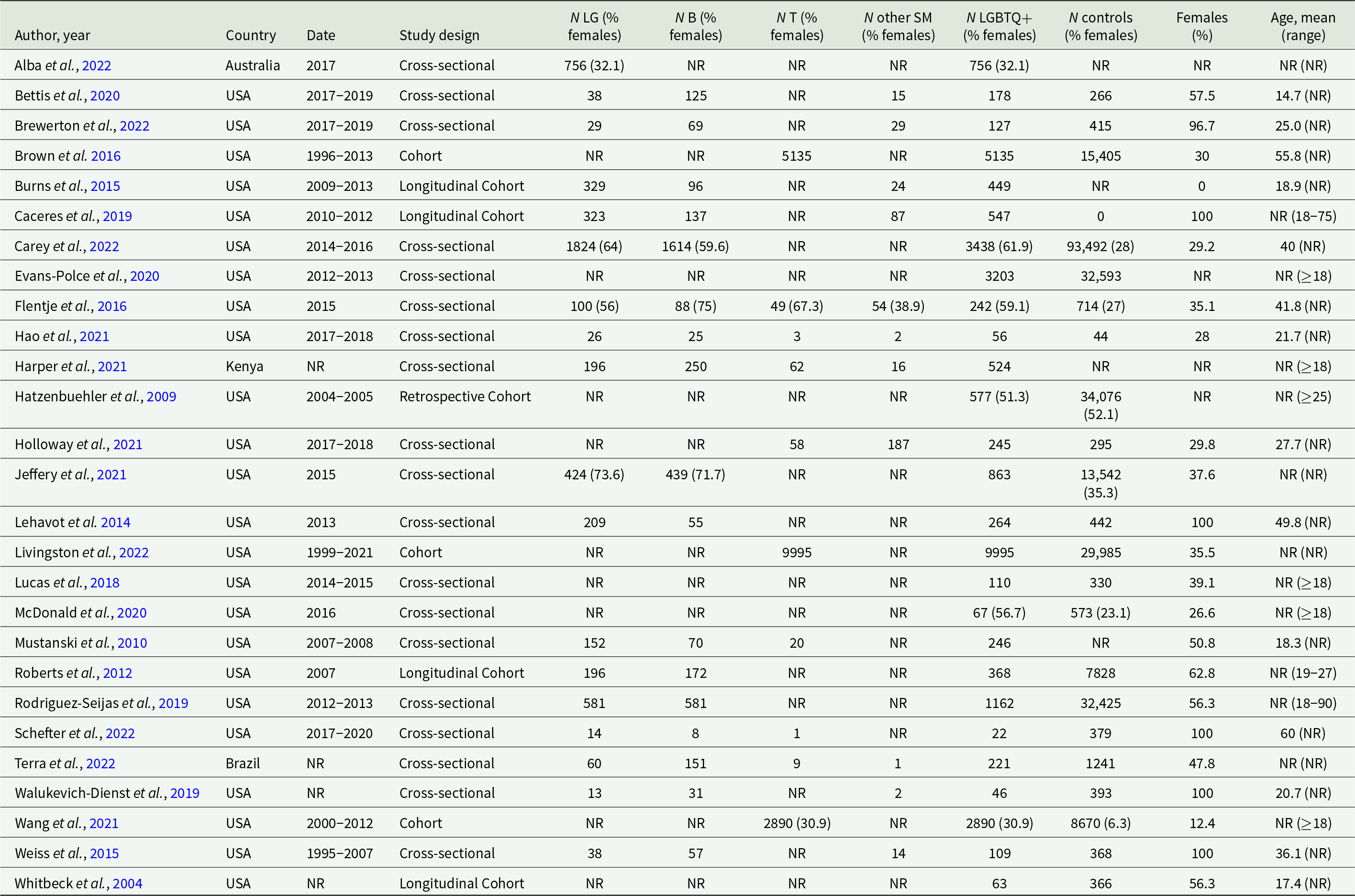

On average across the studies, the assigned sex at birth was female for 53.5% of participants (range: from 0% to 100%). The mean age of participants across the studies ranged from 14.7 to 60 years old (median age across the studies was 26.4). The selected studies were conducted in four countries: US (n = 24; 88.9%), Australia, Brazil and Kenya (n = 1 each; 3.7%). All the studies included were published in the last 20 years. Data collection begun after 2000 for most of the studies (n = 20; 74.1%), before 2000 for three studies (11.1%), and not reported in four studies (14.8%). PTSD was defined according to DSM (n = 16; 59.3%), ICD (n = 3; 11.1%), self-reported (n = 3; 11.1%) and validated psychometric scales (n = 5; 18.5%). Sample weights ranged from 6.3% to 1.3%.

All study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies

Abbreviations: LG: lesbian and gay; B: bisexual; T: transgender; SM: other sexual minorities; USA: United States of America; NR: not reported.

Narrative synthesis of the type of trauma reported across the studies

Besides PTSD diagnosis, 16 (59.3%) studies also collected information about the type of trauma experienced by participants. However, it is worth noting that the studies investigated traumatic experiences without necessarily establishing a temporal or etiological association with the current PTSD status; rather they often reported that information seemingly for descriptive purposes. The reported type of trauma consisted of childhood maltreatment or adverse childhood experiences in three studies, sexual abuse in five studies, interpersonal violence and sexual and violence related to gender minorities in three studies and a cancer diagnosis in one study. Two studies examined violence experienced during both childhood and adulthood, while two veteran studies did not specify the type of traumatic experience, although it is reasonable to assume exposure to military and war-related trauma in these cases. For a more comprehensive overview of the exposure to traumatic experiences across the studies, see Supplementary Table S2.

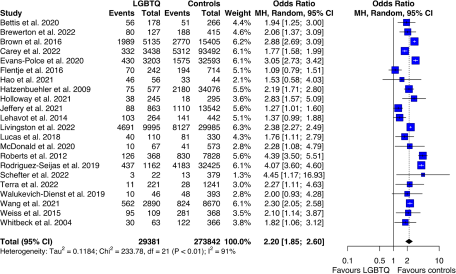

Analysis of PTSD rate among LGBTQ and controls

Twenty-two studies (81.5%) reported outcome data about PTSD among LGBTQ and controls. As displayed in Fig. 2, LGBTQ people showed an increased risk of PTSD compared with matched non-LGBTQ controls, though with significant evidence of between-study heterogeneity (pooled OR: 2.20 [95%CI: 1.85; 2.60]; I 2 = 91%; p < 0.001).

Figure 2. Forest plot of PTSD among LGBTQ people compared with controls (heterosexual or cisgender).

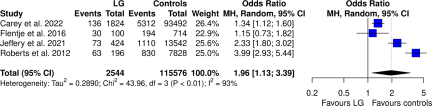

Analysis of PTSD rate among lesbian and gay and controls

Four (14.8%) studies detailed data on PTSD for the lesbian and gay subgroups. Meta-analyses indicated that lesbian and gay people displayed increased risk of PTSD (pooled OR: 1.96 [95% CI: 1.13; 3.39]), though the estimate was affected by significant between-study heterogeneity (I 2 = 93%; p < 0.001). The results are displayed in Fig. 3.

Figure 3. Forest plot of PTSD among LG people compared with controls (heterosexual or cisgender).

Furthermore, two studies (7.4%) compared the risk of PTSD among lesbian and gay: one study detected significant increased risk for lesbian, the other did not find significant differences between the two groups. The pooled estimate was indicating increased risk for lesbian than gay, but the CIs crossed zero (pooled OR: 1.79 [95% CI: 0.74; 4.33]), and there was evidence of high between-study heterogeneity (I 2 = 89%; p < 0.001). The results are displayed in the Supplementary Figure S1.

Analysis of PTSD rate among bisexual and controls

Four studies (14.8%) detailed data on PTSD for the bisexual subgroup. Meta-analyses showed that bisexual people displayed increased risk of PTSD (pooled OR: 2.44 [95% CI: 1.05; 5.66]), with significant between-study heterogeneity affecting the estimate (I 2 = 95%; p < 0.001). The results are displayed in Fig. 4.

Figure 4. Forest plot of PTSD among B people compared with controls (heterosexual or cisgender).

Analysis of PTSD rate among lesbian and gay and bisexual

Seven studies (25.9%) provided data on PTSD rate among lesbian, gay and bisexual. Meta-analysis of the comparison of the PTSD risk among the two groups showed increased risk for bisexual than lesbian and gay (pooled OR: 1.44 [95% CI: 1.07; 1.93]). The between-study heterogeneity was moderate, though statistically significant (I 2 = 61%; p = 0.02). The results are displayed in Supplementary Figure S2.

Analysis of PTSD rate among transgender and controls

Seven studies (25.9%) reported outcome data about PTSD among transgender and cisgender controls. As displayed in Fig. 5, transgender people showed an increased risk of PTSD compared with matched cisgender controls, though with significant evidence of between-study heterogeneity (pooled OR: 2.52 [95% CI: 2.22; 2.87]; I 2 = 79%; p < 0.001).

Figure 5. Forest plot of PTSD among T people compared with heterosexual controls.

Analysis of PTSD rate among queer and controls

Since only one study (3.7%) provided outcome data about queer and controls, meta-analysis was not performed on that outcome, even though the study reported an increased risk for the queer group (OR: 1.84 [95% CI: 1.04; 3.25]).

Publication bias and meta-regression

There was no evidence of publication bias in the primary estimate as shown by Egger’s test p-value > 0.05 and by the funnel plots displayed in the Supplementary Figure S3.

Leave-one-out analysis, in which the meta-analysis of PTSD among LGBTQ and controls was serially repeated after the exclusion of each study, showed that irrelevant changes in the pooled estimate were obtained by excluding each one study. When the study from Flentje et al. (Flentje et al., Reference Flentje, Leon, Carrico, Zheng and Dilley2016) was excluded from the analysis, there was a decrease in the amount of heterogeneity, which, however, was not statistically significant because the value of I 2 = 76% still indicated high between-study heterogeneity. Therefore, there was no evidence of significant outlier effect played by any of the study (leave-one-out data available in Supplementary Table S3).

Meta-regression analyses were performed on the following variables, potentially associated with heterogeneity: (1) the percentage of females in the total sample; (2) the mean age of participants; (3) the country where the study was conducted; (4) assessment of PTSD applied; and (5) the year of publication. In the univariable meta-regression model the variables that resulted significantly correlated with the variance in the risk of PTSD were the country where the study was performed (USA, B: 0.786 [95% CI: 0.611; 0.960]) and the PTSD assessment applied (DSM or ICD, B: 0.996 [95% CI: 0.779; 1.21]; validated psychometric scale, B: −0.402 [95% CI: −0.721; −0.084]). Univariable meta-regression results are displayed in Supplementary Table S4.

GRADE of the evidence

A summary on the risk of bias in all 27 trials is reported in the Supplementary Figures S4 and S5, along with an assessment of the quality of the evidence (Supplementary Table S5). In the GRADE system, the evidence from observational studies is initially set to low, there are then criteria that can be used either to downgrade or upgrade (see further information in the Supplementary Material). The quality of the evidence was rated low for the main analysis of LGBTQ vs. controls. For the secondary analyses, the evidence was rated from low to very low.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to describe the risk of PTSD among LGBTQ people. Our results indicate that LGBTQ people are at increased risk of PTSD compared to matched non-LGBTQ controls. These findings confirm the relationship between sexual variant status and exposure to trauma (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, 2015; Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Lynch, Hinds, Gatsby, DuVall and Shipherd2022; Marchi et al., Reference Marchi, Arcolin, Fiore, Travascio, Uberti, Amaddeo, Converti, Fiorillo, Mirandola, Pinna, Ventriglio and Galeazzi2022a; Walters et al., Reference Walters, Chen and Breiding2013). For example, violence provoked by the same partner and sexual assault in adulthood are disproportionately more prevalent among minorities of sexual orientation (Trombetta and Rollè, Reference Trombetta and Rollè2022), and individuals with minority sexual orientation reported a high frequency, severity and persistence of physical and sexual abuses during childhood (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Rosario, Corliss, Koenen and Austin2012). Interestingly, research evidence on the psychological consequences of the exposure to trauma, including adverse childhood experience, are not limited to PTSD (Elkrief et al., Reference Elkrief, Lin, Marchi, Afzali, Banaschewski, Bokde, Quinlan, Desrivières, Flor, Garavan, Gowland, Heinz, Ittermann, Martinot, Martinot, Nees, Orfanos, Paus, Poustka, Hohmann, Fröhner, Smolka, Walter, Whelan, Schumann, Luykx, Boks and Conrod2021; Marchi et al., Reference Marchi, Elkrief, Alkema, van Gastel, Schubart, van Eijk, Luykx, Branje, Mastrotheodoros, Galeazzi, van Os, Cecil, Conrod and Boks2022b, Reference Marchi, Artoni, Longo, Magarini, Aprile, Reggianini, Florio, Fazio, Galeazzi and Ferrari2020). In this perspective, the association between the sexual variant status and experiences of traumatization may be relevant also for other forms of psychopathology. Intersectionality may be another appropriate model for understanding the different impact of trauma on LGBTQ people. In our review, we included six studies conducted on samples of veterans (Brown and Jones, Reference Brown and Jones2016; Carey et al., Reference Carey, Leard-Mann, Lehavot, Jacobson, Kolaja, Stander and Rull2022; Holloway et al., Reference Holloway, Green, Pickering, Wu, Tzen, Goldbach and Castro2021; Jeffery et al., Reference Jeffery, Beymer, Mattiko and Shell2021; Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Lynch, Hinds, Gatsby, DuVall and Shipherd2022; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Ganulin, Dretsch, Taylor and Cabrera2020), all showing that LGBTQ veterans are at increased risk of PTSD compared to their non-LGBTQ peers, independent of the experience of traumatization to which they may have been exposed. Such higher risk of PTSD has been observed also in other LGBTQ people belonging to vulnerable populations, such as with HIV or part of racial and ethnic minorities (Glynn et al., Reference Glynn, Mendez, Jones, Dale, Carrico, Feaster, Rodriguez and Safren2021). For these populations, treatment seeking and adherence are still a challenge, and suffering from mental health problems, such as PTSD, may be playing as a mediator (Marchi et al., Reference Marchi, Magarini, Chiarenza, Galeazzi, Paloma, Garrido, Ioannidi, Vassilikou, de Matos, Gaspar, Guedes, Primdahl, Skovdal, Murphy, Durbeej, Osman, Watters, van den Muijsenbergh, Sturm, Oulahal, Padilla, Willems, Spiritus-Beerden, Verelst and Derluyn2022c; Oni et al., Reference Oni, Glynn, Antoni, Jemison, Rodriguez, Sharkey, Salinas, Stevenson and Carrico2019).

Although the comparison of the PTSD risk between the sexual and gender minority groups was limited by the lack of data from some less studied populations, such as intersex, our data suggest that among LGBTQ groups, the highest risk of PTSD was found for transgender people, followed by bisexuals. This is consistent with previous evidence estimating increased risk of interpersonal violence for transgender people, as well as higher risk of depression, anxiety, substance use and suicidality (Valentine and Shipherd, Reference Valentine and Shipherd2018). Research on bisexual individuals, instead, suggested that they may be potentially excluded from LGBTQ community initiatives, due to the stereotypes according to which bisexuals are promiscuous or that bisexuality is ‘just a phase’. Indeed, from a social perspective, bisexuality—and to some extent also intersexuality—challenges binary thinking and normative assumptions. Invisibility and lack of community support could explain the higher incidence of mental health problems, including PTSD (Baams et al., Reference Baams, Grossman and Russell2015). Embracing an ethical perspective able to account for fluidity and multiplicity, such as queer ethics, might create a more inclusive framework that accounts for the experiences of all members of the LGBTQ communities (Däumer, Reference Däumer1992).

By looking at the contribution of each study in the analyses, it is possible to observe that the studies from Flentje et al. (Flentje et al., Reference Flentje, Leon, Carrico, Zheng and Dilley2016) and Mustanski et al. (Mustanski et al., Reference Mustanski, Garofalo and Emerson2010) provided estimates that were less coherent with the others. This can be due to the sampling strategies implemented: Mustanski et al. enrolled a sample made only of sexual minority individuals and observed a small number of cases of PTSD; Flentje et al. made comparison of PTSD rates by sexual orientation or by gender identity; therefore, the comparison of PTSD risk by sexual orientation could include also transgender individuals. This intuition is supported by the fact that the comparison between transgender and cisgender provided by Flentje et al. was coherent with the others. In addition, the sample by Flentje et al. was made of homeless people, which is already a population with relevant vulnerabilities for mental health. This is supported also by the results of another study included in this review and conducted on a sample of homeless people (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Beld, Khoddam-Khorasani, Flentje, Kersey, Mousseau, Frank, Leonard, Kevany and Dawson-Rose2021) providing estimates with CI crossing 1. Consequently, the estimate of higher risk of PTSD for transgender homeless compared to cisgender homeless people provided by Flentje et al. is consistent with the intersectionality model proposed above in this section. The analysis of the forest plot of the primary comparison showed substantial between-study heterogeneity. Despite this, leave-one-out analysis did not detect significant outlier effects. Univariable meta-regression found that the pooled estimate of PTSD risk was affected by the country, although with much imbalance in the distribution of the classes (i.e., 21 out of 22 studies were conducted in USA) and the assessment of PTSD applied. Specifically, studies assessing PTSD by applying diagnostic manuals criteria (i.e., DSM or ICD) could provide lower effect size for the pooled odds of PTSD among LGBTQ. This is consistent with previous evidence of only moderate diagnostic agreement between the systems used, with likely stricter definition of PTSD applied in the diagnostic manuals (Elmose Andersen et al., Reference Elmose Andersen, Hansen, Lykkegaard Ravn and Bjarke Vaegter2022; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Ross, Ashwick, Armour and Busuttil2017). Nevertheless, the high heterogeneity detected would not seem to be a limitation but a possible indicator of the trend of PTSD in LGBTQ people through time and in its possible declination across different samples. The low detection of publication bias seems to support this interpretation.

Limitations

The present study yielded robust findings; however, it should be interpreted considering some limitations. First, the heterogeneity on the PTSD assessment used in the studies. Most of the studies considered DSM and ICD definitions of PTSD, which consisted, respectively, in the presence of a traumatic event involving exposure to real or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence (criterion A of DSM) or a protracted response to a stressful event or situation of an exceptionally threatening or catastrophic nature, which is likely to cause distress to almost anybody (ICD). Evaluations tailored on specific stress experienced by LGBTQ people (e.g., consistent with the Minority Stress Model) are lacking. These could lead to more accurate understanding of the risk of post-traumatic stress to which this population is exposed. Second, some studies included in the final selection did not provide all information about the sample composition (i.e., four studies did not report participants age and two studies did not report the sex assigned at birth of participants). This lack of information might have affected the results of meta-regression. Third, although the Egger test did not detect publication bias in any of the analyses, the funnel plot of the primary comparison seems to suggest that publication bias might be present. That may be due to between-study heterogeneity, which can give that plotting especially for those studies with large standard error. In addition, the number of the studies included in the subgroups meta-analyses was <10, which was not enough to inform about publication bias (Sterne et al., Reference Sterne, Sutton, Ioannidis, Terrin, Jones, Lau, Carpenter, Rücker, Harbord, Schmid, Tetzlaff, Deeks, Peters, Macaskill, Schwarzer, Duval, Altman, Moher and Higgins2011). Finally, we could not achieve our initial aim to detail PTSD risk for each LGBTQ group (i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer) because many studies did not consider these separated groups. In addition, there is limited research with enough participants that could be used to validate these findings for other sexual and gender minority groups, such as intersex people. There is an important need for international research to explore this area further.

Implications for research and practice

Traumatization and post-traumatic stress among sexual minorities are unaddressed issues. Critically, the concept of trauma should be investigated also beyond that considered by the diagnostic systems, especially for minority populations, such as LGBTQ. For instance, the literature is highlighting the negative effect of repeated interpersonal microaggressions. These are verbal expressions, attitudes and behaviours, which, intentionally or unintentionally, communicate hostile, derogatory, negative, prejudicial and offensive messages towards members of minority groups (Johnston and Nadal, Reference Johnston, Nadal and Sue2010; Nadal et al., Reference Nadal, Whitman, Davis, Erazo and Davidoff2016). The prefix micro does not describe the quality or the impact of these aggressions but rather the subtle way in which this type of discrimination occurs, making microaggressions very difficult to recognize, study and demonstrate, eluding the available diagnostic criteria. Microaggression may be considered benign or harmless by the perpetrator, with the risk to become pervasive and automatic in daily interactions. Research has shown that experiencing microaggressions can damage people’s mental health and lead to chronic stress, depression, anxiety and low self-esteem (Flentje et al., Reference Flentje, Heck, Brennan and Meyer2020; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Siegel, Wolf, Narikuzhy, Roth, Hatchard, Lanius, Schneider, Lloyd, McKinnon, Heber, Smith and Lueger-Schuster2022).

On a primary prevention level, programs and guidelines should be developed and employed in violence prevention to strengthen protective factors and foster resilience. Such efforts should be intensified for LGBTQ people with the aim of reducing minority stress and the barriers to disclosure and seeking help among the victims. For example, psychoeducation campaigns aimed at reducing victim-blaming and promoting intervening behaviours by bystanders has shown to be an effective mean of preventing interpersonal violence in societal settings (Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Krueger, Greitemeyer, Vogrincic, Kastenmüller, Frey, Heene, Wicher and Kainbacher2011; Wijaya et al., Reference Wijaya, Roberts and Kane2022). Also, awareness and education campaigns, associated with severe sentences for sexual minority-related crimes, could be valid responses to reduce the risk of violence and increase the security of LGBTQ people. Arguably, intersectional analysis would make it possible to give a modern reading of social discrimination phenomena. Embracing this would allow better understanding of systemic, institutional and social disparities contributing to the experiences of discrimination of the LGBTQ communities (Bendl et al., Reference Bendl, Bleijenbergh, Henttonen and Mills2015).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796023000586

Availability of data and materials

The codes for reproducing the analyses can be accessed here: https://github.com/MattiaMarchi/Meta-Analysis–PTSD-Among-LGBTIQ-people.

Financial support

His research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None