1. Introduction

Global warming and its effects on the climate system is one of the greatest threats to all life on Earth. Therefore, there is an increasing interest in understanding the global carbon (C) cycle as global warming is tightly coupled with the global C cycle (Crowther et al. Reference Crowther, Todd-Brown, Rowe, Wieder, Carey and Machmuller2016; IPCC Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani, Connors, Pean, Berger, Caud, Chen, Goldfarb, Gomis, Huang, Leitzell, Lonnoy, Matthews, Maycock, Waterfield, Yelekci, Yu and Zhou2021). Soil plays a critical role in the global C cycle; it stores a huge amount of C as soil organic carbon (SOC) and produces a large emission flux of carbon dioxide (CO2), the primary greenhouse gas, from the soil to the atmosphere through SOC decomposition (IPCC Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani, Connors, Pean, Berger, Caud, Chen, Goldfarb, Gomis, Huang, Leitzell, Lonnoy, Matthews, Maycock, Waterfield, Yelekci, Yu and Zhou2021). Hence, an accurate assessment of the capability of soil to preserve SOC is essential to improve our ability to predict the future of Earth’s climate.

Radiocarbon (14C) can be a powerful tool to quantitatively assess the SOC cycling rate in soils because it provides information on the timescale of C as it has been preserved in soils since its fixation and incorporation from the atmosphere (Schuur et al. Reference Schuur, Carbone, Hicks Pries, Hopkins, Natali, Schuur, Druffel and Trumbore2016; Trumbore Reference Trumbore2009). Briefly, the abundance of natural 14C, cosmogenically produced at a moderately constant rate in the upper atmosphere, can be used to identify stable SOC pools that are old enough for significant radioactive decay (with a half-life of 5730 years) in soils.

Accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) is the most widely used and extremely sensitive technique for 14C measurements. Recently, the demand for AMS-14C measurements of soil samples has been increasing due to the great benefit of 14C analysis in studying SOC cycling (Saito-Kokubu et al. Reference Saito-Kokubu, Fujita, Watanabe, Matsubara, Ishizaka, Miyake, Nishio, Kato, Ogawa, Ishii, Kimura, Shimada and Ogata2023; Schuur et al. Reference Schuur, Carbone, Hicks Pries, Hopkins, Natali, Schuur, Druffel and Trumbore2016). However, two critical difficulties occur in conducting AMS-14C measurements for soil samples with high reliability and accuracy, both of which are encountered during AMS sample preparation. Sample preparation primarily comprises the combustion of soil samples to generate CO2 and graphitization through the catalytic reduction of CO2. The first challenge appears mainly in the combustion process. C-containing impurities associated with chemicals are introduced to the samples, contaminating the samples with modern (14C-enriched) C (MC) (Mueller and Muzikar Reference Mueller and Muzikar2002; Schleicher et al. Reference Schleicher, Grootes, Nadeau and Schoon1998; Vandeputte et al. Reference Vandeputte, Moens, Dams and van der Plicht1998). The second difficulty appears in the graphitization process. Sulfur (S)-containing impurities (S oxides) generated from the soil samples during combustion are introduced to the samples, inhibiting formation of graphite, the typical target for AMS-14C measurement (Minami et al. Reference Minami, Miyata and Nakamura2011; Thomsen and Gulliksen Reference Thomsen and Gulliksen1992; Zazzo et al. Reference Zazzo, Lebon, Chiotti, Comby, Delqué-Količ, Nespoulet and Reiche2013). The effect of S-containing impurities on graphite formation might be more critical for soil samples than other samples because S is present in organic matter in all soils (Schnug et al. Reference Schnug, Haneklaus, Bloem and Lal2017). Various methods, for example, using silver (Ag) wire and Sulfix reagent (a mixture of tricobalt tetra-oxide and Ag), have been attempted to remove S-containing impurities during sample preparation (Boutton et al. Reference Boutton, Wong, Hachey, Lee, Cabrera and Klein1983; Hua et al. Reference Hua, Jacobsen, Zoppi, Lawson, Williams, Smith and McGann2001; Koarashi et al. Reference Koarashi, Atarashi-Andoh, Ishizuka, Miura, Saito and Hirai2009; Nakajima et al. Reference Nakajima, Wada, Matsuzaki and Suzuki2004; Zazzo et al. Reference Zazzo, Lebon, Chiotti, Comby, Delqué-Količ, Nespoulet and Reiche2013). However, few studies have comprehensively examined the removal of S-containing impurities and MC contamination during sample preparation for different preparation methods.

Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the applicability of sample preparation methods to the 14C dating of soil samples with sufficient accuracy for C cycle studies. We conducted two investigations using three sample preparation methods for AMS. The first test is to evaluate the effects of the methods on S removal and 14C dating based on the graphitization conditions and AMS-14C measurements for S-rich soil samples. The second test is to quantify MC contamination from the methods based on the AMS-14C measurement of a 14C-dead charred wood sample.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample preparation methods

This study considered three common methods for removing S-containing impurities during sample preparation: (1) Ag foil (Boutton et al. Reference Boutton, Wong, Hachey, Lee, Cabrera and Klein1983; Koarashi et al. Reference Koarashi, Atarashi-Andoh, Ishizuka, Miura, Saito and Hirai2009), (2) Ag wire (Hua et al. Reference Hua, Jacobsen, Zoppi, Lawson, Williams, Smith and McGann2001; Nakajima et al. Reference Nakajima, Wada, Matsuzaki and Suzuki2004), and (3) Sulfix (Vandeputte et al. Reference Vandeputte, Moens, Dams and van der Plicht1998; Nakajima et al. Reference Nakajima, Wada, Matsuzaki and Suzuki2004; Zazzo et al. Reference Zazzo, Lebon, Chiotti, Comby, Delqué-Količ, Nespoulet and Reiche2013; Beck et al. Reference Beck, Caffy, Delqué-Količ, Moreau, Dumoulin, Perron, Guichard and Jeammet2018). Details of the methods and preparation conditions are described below.

In the Ag foil method, a solid sample was flame-sealed in prebaked quartz tubes under vacuum, with approximately 1 g of copper oxide (CuO) wire and 0.5 g of reduced copper (Cu) wire. Ag foil (length 50 mm, width 5 mm, thickness 0.0045 mm, purity 99.99%, Shoko Co., Ltd.) was also added into the tubes to remove S-containing impurities. The samples in the sealed tubes were combusted at 850°C for 2 hr to generate CO2. After that, CO2 in the generated gas was cryogenically purified and recovered using a vacuum line.

The Ag wire method is mostly the same as the Ag foil method. The only difference between the two methods was using an Ag wire (diameter 0.1 mm, length 10 mm, purity >99.5%, 5 pieces, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Japan) instead of Ag foil.

The Sulfix method requires a two-step procedure (Nakajima et al. Reference Nakajima, Wada, Matsuzaki and Suzuki2004; Vandeputte et al. Reference Vandeputte, Moens, Dams and van der Plicht1998). First, similar to the other methods, a solid sample was flame-sealed in quartz tubes under vacuum, with approximately 1 g of CuO wire and a piece of platinum (Pt). The samples in the sealed tubes were combusted at 850°C for 2 hr, and the CO2 generated from the samples was cryogenically purified, as before. Second, the purified CO2 was transferred into prebaked Pyrex tubes where three grains of Sulfix reagent (diameter 0.8–2.4 mm, Kishida Chemical Co., Ltd., Japan) were placed, and the tubes were flame-sealed under vacuum. The tubes were baked at 500°C for 1 hr to react the S-containing impurities in the gas with Sulfix reagent, after which the CO2 in the tubes was cryogenically purified and recovered using a vacuum line.

Table 1 summarizes the preparation methods investigated in this study. Regarding the Ag foil method, organic materials adhering to the surface of Ag foil can be a primary source of MC contamination in the AMS-14C measurement. Therefore, Ag foils subjected to various pretreatments to decontaminate the surface were used for comparison. The decontamination pretreatments for Ag foil include washing with ultrapure water, ethanol, and acetone and prebaking at 500°C and 800°C for 3 hr.

Table 1. Preparation methods for removing sulfur-containing impurities

The Ag foil method has been commonly performed through the single-step procedure as described above. However, testing a two-step procedure in the Ag foil method still merits consideration especially in comparison with the Sulfix method under the same preparation condition. Therefore, the following two-step method was also examined in this study. A solid sample was combusted at 850°C for 2 hr in sealed quartz tubes under vacuum, with approximately 1 g of CuO wire and 0.5 g of Cu wire. The resulting CO2 was cryogenically purified and transferred into prebaked Pyrex tubes where Ag foil (prebaked at 500°C for 3 hr) was placed. The tubes were baked at 500°C for 1 hr to react the S-containing impurities with Ag foil, and the CO2 in the tubes was cryogenically purified again and recovered.

Regarding the Sulfix method, the effect of the amount of Sulfix on the AMS-14C measurements was also examined using different numbers (and thus, different amounts) of Sulfix grains (15 and 45 grains). Furthermore, the following single-step method was evaluated to investigate the effect of Sulfix on the AMS-14C measurement. Three Sulfix grains were flame-sealed in quartz tubes together with the Aso-3 sample, CuO, and Pt chip, and they were combusted simultaneously at 850°C for 2 hr. The CO2 in the quartz tubes was then cryogenically purified and recovered, as before.

2.2. Graphitization and AMS-14C measurement

The purified CO2 from the different preparation methods was converted into graphite by reducing it with hydrogen gas (H2) at 650°C in the presence of iron (Fe) powder (prereduced with H2 at 450°C) as a catalyst (Kitagawa et al. Reference Kitagawa, Masuzawa, Nakamura and Matsumoto1993). The 14C content of the sample was measured on the graphite target using AMS at the Tono Geoscience Center, Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA-AMS-TONO-5MV and JAEA-AMS-TONO-300kV, Xu et al. Reference Xu, Ito, Iwatsuki, Abe and Watanabe2000; Saito-Kokubu et al. Reference Saito-Kokubu, Fujita, Watanabe, Matsubara, Ishizaka, Miyake, Nishio, Kato, Ogawa, Ishii, Kimura, Shimada and Ogata2023).

A subsample of the purified CO2 was used to measure the stable C isotope ratio (δ13C) with an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IsoPrime100, Isoprime Ltd., UK), and the δ13C value (‰) was used to correct the mass-dependent isotopic fractionation effect on the 14C result (Stuiver and Polach Reference Stuiver and Polach1977). The 14C results were reported as percent MC (pMC) with a blank correction. This study prepared the sample processing blank using a quality control material, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)-C1 sample (carbonate with a recommended 14C activity value of 0.00 pMC; Rozanski et al. Reference Rozanski, Stichler, Gonfiantini, Scott, Beukens, Kromer and van der Plicht1992; IAEA 2014). The blank correction was made by subtracting the 14C activity value of the blank sample from that of the measured sample. In the blank preparation, CO2 generation from the IAEA-C1 sample was achieved through the carbonate reaction with phosphoric acid without any combustion processes (i.e., without using any chemicals for combustion or sulfur oxide removal). Therefore, the 14C results reported here can be used to compare the 14C-contamination effects of the preparation methods, including contaminations from the chemicals used for combustion and S-impurity removal in the methods. The pMC values measured for the IAEA-C1 were 0.13% ± 0.06% (1std) and 0.40% ± 0.01% for JAEA-AMS-TONO-5MV and JAEA-AMS-TONO-300kV, respectively (Saito-Kokubu et al. Reference Saito-Kokubu, Fujita, Miyake, Watanabe, Ishizaka, Okabe, Ishimaru, Matsubara, Nishizawa, Nishio, Kato, Torazawa and Isozaki2019).

2.3. Application of the preparation methods to soil samples

The methods were applied to soil samples with different S contents to confirm whether they work well in removing S-containing impurities during sample preparation and forming graphite for AMS-14C measurements. This study used three soil samples (Soil-1, Soil-2, and Soil-3) collected in sulfur-rich hot spring areas (Takayu and Tsuchiyu) in Fukushima, Japan. The soil samples were dried, sieved with a 2-mm mesh, ground to a fine powder to homogenize the samples, and analyzed for organic C and S contents (as weight percent: wt%) using an elemental analyzer (vario PYRO cube, Elementar, Germany). The organic C contents were 6.1, 3.0, and 3.8 wt% for Soil-1, Soil-2, and Soil-3, respectively. The organic S contents were 6.9, 3.7, and 1.4 wt% for Soil-1, Soil-2, and Soil-3, respectively. In addition to the soil samples, sulfanilamide (an organic sulfur compound with a high S content of 18.6 wt%, Elementar, Germany) and a quality control material IAEA-C5 (subfossil wood, S content of 1.0 wt%) were also used to evaluate the methods.

The methods tested were the Ag foil (without any treatments for decontamination of foil surface), two-step Ag foil, and Sulfix (with 3 and 15 grains) methods. After preparing the different samples with different methods, AMS-14C measurements were conducted in the same manner as before. Then, the conditions of graphite formation, the graphitization yields (defined as the percentage of the C amount of formed graphite to the C amount of CO2 used for graphitization), and the AMS-14C measurement results were examined and compared.

2.4. Evaluation of modern carbon contamination from the preparation methods

The MC contamination introduced by these methods was evaluated based on the AMS-14C measurement of a charred wood sample (Aso-3). The Aso-3 sample was formed by the volcanic eruption of Mt. Aso more than 100,000 years ago and comprises dead carbon (i.e., it does not contain 14C). The different preparation methods used approximately 3.5 mg of the Aso-3 sample as a solid sample.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Applicability of the preparation methods to soil samples

The soil samples that differ in organic S content were prepared with the Ag foil and Sulfix methods, and the results confirmed that all sample preparations (N = 18) successfully generated graphite (Table 2). Moreover, the AMS-14C measurements were successful for all graphite targets, indicating that the preparation methods effectively removed S-containing impurities during sample preparation and can at least be used to prepare soil samples with an organic S content <6.9 wt%. As the total S contents in soils typically range from 0.01 wt% to 3.5 wt% (Schnug et al. Reference Schnug, Haneklaus, Bloem and Lal2017), the preparation methods can be applied to a broad range of soil samples collected from forests and even agricultural (i.e., fertilizer-adopted) ecosystems developed on different parent materials globally. Furthermore, with these preparation methods, the graphitization and AMS-14C measurements were achieved for sulfanilamide, indicating that these preparation methods are potentially applicable to soil samples with an organic S content of up to 18 wt%.

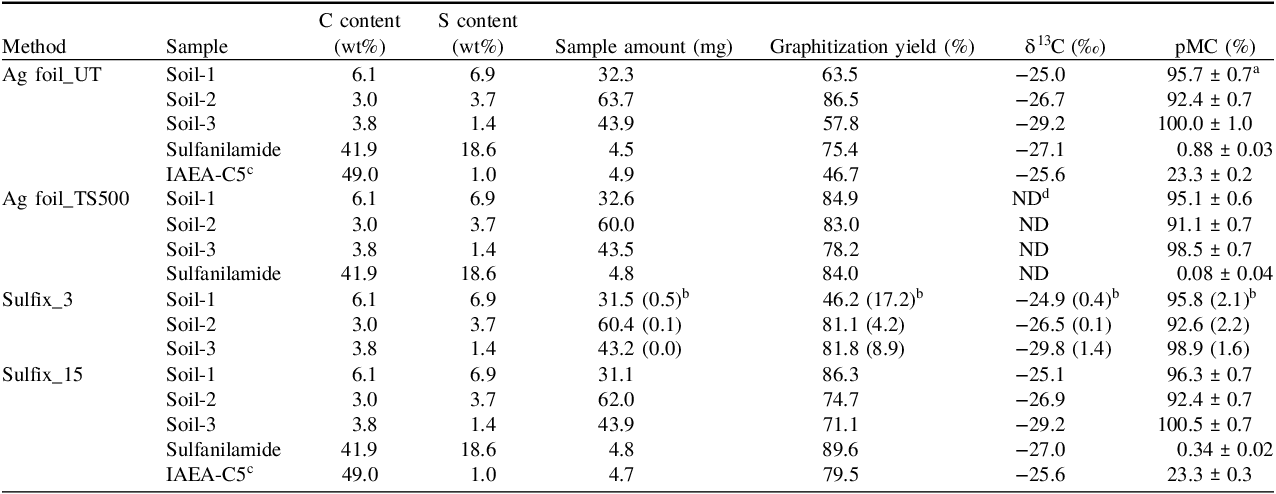

Table 2. Graphitization yields and accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS)-14C measurement results for different samples with different preparation methods

a Errors represent the counting errors in the AMS-14C measurement.

b Mean and standard deviation (in parentheses) of three replicate samples (N = 3).

c Subfossil wood sample provided as a quality control material by the IAEA (Rozanski et al. Reference Rozanski, Stichler, Gonfiantini, Scott, Beukens, Kromer and van der Plicht1992; IAEA 2014).

d ND: Not determined.

The graphitization yield of the preparation methods was 32%–90% for the samples with different S contents, including soils, sulfanilamide, and subfossil wood. Although the graphitization yield was below 50% for some samples, no clear dependences of the graphitization yield on the sample type and preparation method were observed. However, lower graphitization yields for Soil-1 (with a high S content) in the Sulfix_3 method may suggest an insufficient surface area of Ag reagent in the method to completely absorb S compounds, given that the estimated surface area of 3 grains of Sulfix reagent (approximately 0.06–0.3 cm2) was significantly smaller than those of 15 grains of Sulfix reagent (approximately 0.54–2.71 cm2) and Ag foil (2.5 cm2). Nakajima et al. (Reference Nakajima, Wada, Matsuzaki and Suzuki2004) reported a similar range of graphitization yield (29%–90%) for preparing elemental C (EC) in aerosol samples, with preparation methods using Ag wire, Sulfix reagent (15–30 mg, corresponding to the amount of 3 grains of Sulfix reagent in this study), and their combination. However, they further reported that graphite could not be obtained from three of the 11 EC samples, even though such preparation methods were employed to remove S-containing impurities. Moreover, Minami et al. (Reference Minami, Miyata and Nakamura2011) reported that Sulfix treatment for CO2 (with 30–40 mg of Sulfix reagent at 380°C for 1 hr) made it possible to form graphite from the samples (polyethersulfone) previously prevented from forming graphite with preparation methods using Ag wire and an n-pentane/liquid N2 trap. Hence, the cause of the variability in graphitization yield is not yet fully understood and further work is needed for optimization of the methods.

The δ13C values obtained for the soil and sulfanilamide samples using the different preparation methods were consistent with each other (Table 2), and the values measured for the IAEA-C5 (subfossil wood sample) were in good agreement with the reference value (−25.5‰, with a standard deviation of 0.7‰; Rozanski et al. Reference Rozanski, Stichler, Gonfiantini, Scott, Beukens, Kromer and van der Plicht1992; IAEA, 2014). The results support that the preparation methods have little influence on the δ13C determination.

Regarding the 14C measurements for soil and subfossil wood samples, no clear difference in the pMC value was observed between the preparation methods while considering the analytical uncertainty in the measurement and the standard deviation of the replicate samples (Table 2). However, with the 14C measurements for sulfanilamide, the pMC values were very low and differed between the preparation methods. The pMC value obtained for sulfanilamide was low in the order of Ag foil_TS500 < Sulfix_15 < Ag foil_UT, which is consistent with the results of the MC contamination from the different preparation methods (see Section 3.2). Generally, the pMC values measured for IAEA-C5 were consistent with the reference value (23.05% ± 0.02%; Rozanski et al. Reference Rozanski, Stichler, Gonfiantini, Scott, Beukens, Kromer and van der Plicht1992; IAEA, 2014).

The conventional 14C ages estimated for the different samples were compared between the Ag foil and Sulfix methods (Table 3). The results show that the methods give a similar 14C age for each of the three soil samples, indicating that for the studied soils with a 14C activity of approximately 90 pMC and higher, the preparation methods for the S-impurity removal do not play any role in the MC contamination. The 14C ages estimated for the IAEA-C5 (reference value: 11,790 ± 10 years BP) were 11,710 ± 70 years BP and 11,690 ± 90 years BP for the Ag foil and Sulfix methods, respectively, indicating that the preparation methods have a negligible impact on the determination of the 14C ages for samples at least younger than approximately 12,000 yr BP. However, the 14C age for sulfanilamide with the Ag foil method (∼38,000 yr BP) was estimated to be significantly younger than those with the Sulfix method (∼45,600 yr BP) and the two-step Ag foil method (∼57,000 yr BP with a large uncertainty), probably due to MC contamination during sample preparation (see Section 3.2).

Table 3. Conventional 14C ages estimated for different samples with different preparation methods

a Errors represent the counting errors in the AMS-14C measurement.

b Mean and standard deviation (in parentheses) of three replicate samples (N = 3).

c Subfossil wood sample provided as a quality control material by the IAEA (Rozanski et al. Reference Rozanski, Stichler, Gonfiantini, Scott, Beukens, Kromer and van der Plicht1992; IAEA 2014).

d Not available.

3.2. Modern carbon contamination from the different preparation methods

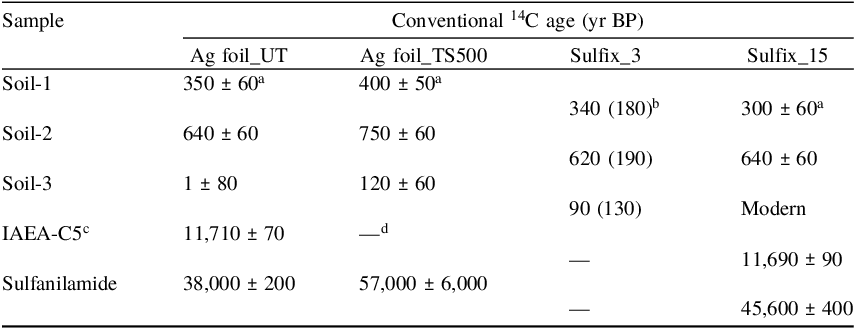

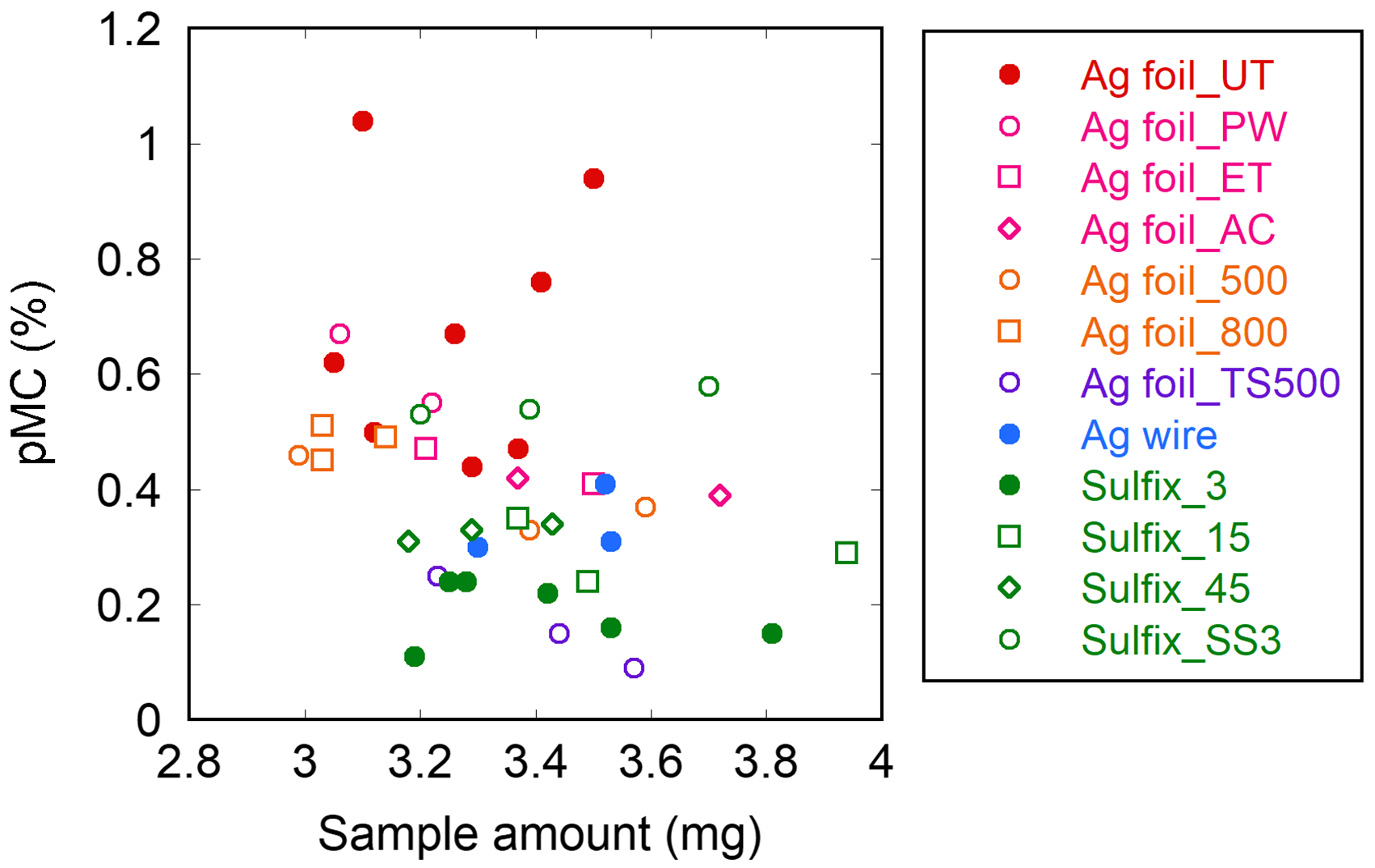

For the different preparation methods for removing S-containing impurities, contamination by MC, which is introduced during sample preparation, was evaluated based on the AMS-14C analysis of the 14C-dead (Aso-3) sample (Figure 1; see also Table S1 in the Appendix for numerical data for all measurements). These methods showed different pMC values from 0.16% to 0.64% with an average of 0.40%. As a general tendency, the pMC value was high when the sample was prepared with the Ag foil method and low when the sample was prepared with the Sulfix method. However, more importantly, the two-step Ag foil method (Ag foil_TS500) showed the lowest pMC values and thus had the lowest levels of MC contamination among the methods investigated in the present study. This finding demonstrates that two-step procedure is the key to reducing MC contamination during sample preparation across different (Ag foil and Sulfix) methods. A weak negative correlation (r = −0.32, p < 0.05) was found between the pMC value and the amount of sample (Figure 2), but the figure also showed that this correlation was probably due to the methodological bias that overall, the amounts of sample used in the Ag foil methods were smaller than those in the Sulfix methods. Therefore, the results indicate that the level of MC contamination largely depends on the used method.

Figure 1. pMC values obtained for the Aso-3 sample with different preparation methods. The numbers in parentheses represent the numbers of replicate samples, and the error bars represent the standard deviation of the replicate samples. UT: Untreated Ag foil; PW: Ag foil washed with ultrapure water; Ag foil washed with ethanol; AC: Ag foil washed with acetone; 500: Ag foil pre-baked at 500°C; 800: Ag foil pre-baked at 800°C; 500TS: Two-step preparation with Ag foil pre-baked at 500°C; 3: 3 grains of Sulfix; 15: 15 grains of Sulfix; 45: 45 grains of Sulfix; SS3: Single-step preparation with 3 grains of Sulfix.

Figure 2. pMC values obtained for different amounts of the Aso-3 sample with different preparation methods.

The pretreatments to decontaminate the Ag foil surface effectively reduced MC contamination in the Ag foil method (Figure 1), except when washing with ultrapure water (Ag foil_PW). The pMC value for the Aso-3 sample decreased from 0.64% (for Ag foil_UT) to 0.42% (for Ag foil_ET and Ag foil_AC) while washing the surface with organic solvents. Prebaking the Ag foil also decreased the pMC value to 0.44% (for Ag foil_500 and Ag foil_800). Hence, organic materials on the Ag foil surface are proposed to be a crucial source of MC contamination during sample preparation, and these pretreatment procedures help reduce contamination levels in the Ag foil method. Here, it should be emphasized again that even after the pretreatment for Ag foil, introducing the two-step procedure can further reduce MC contamination (Ag foil_500 versus Ag foil_TS500).

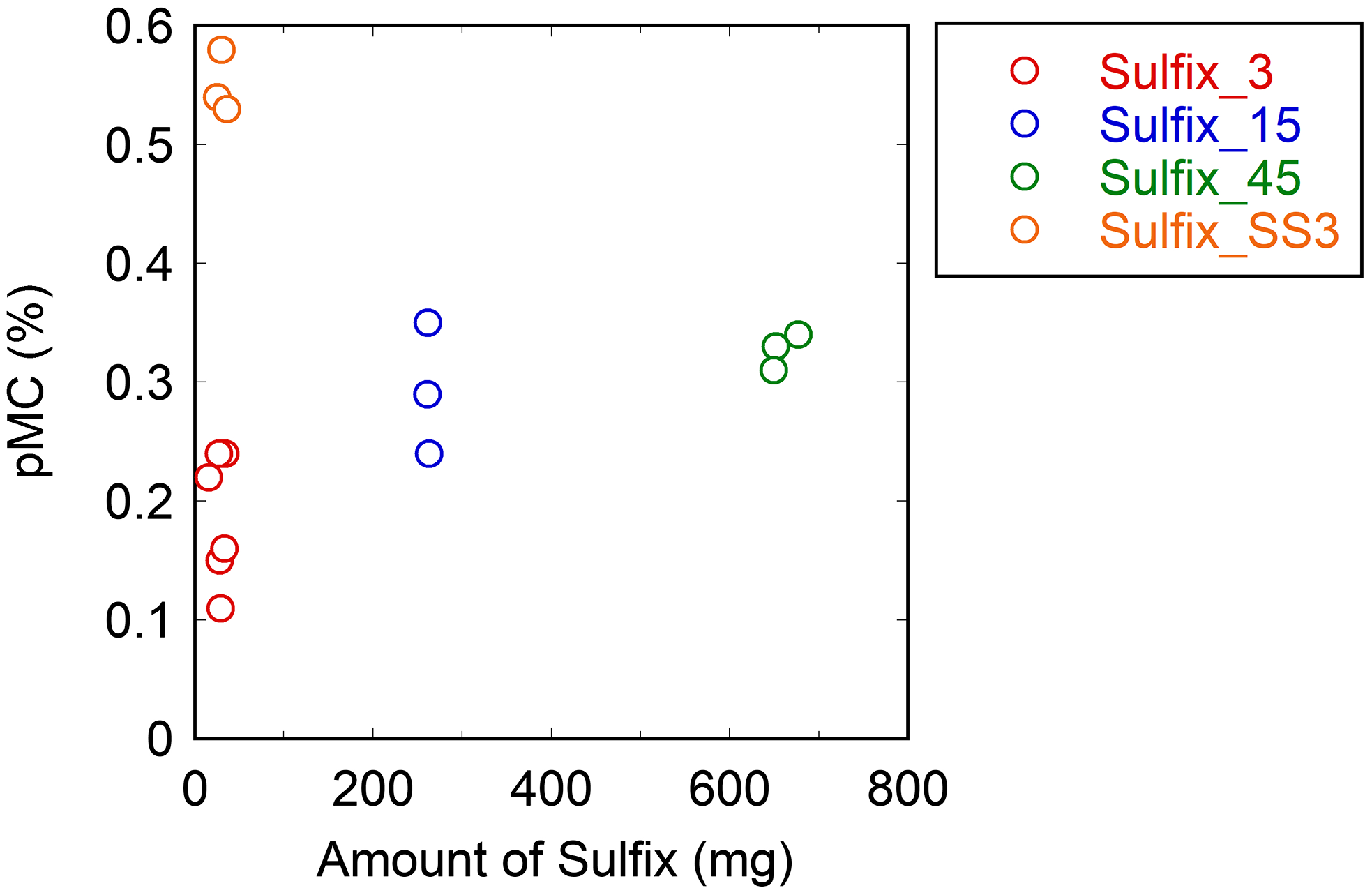

The Sulfix methods, except for the single-step Sulfix method (Sulfix_SS3), had lower pMC values than the Ag foil methods with single-step procedure (Figure 1). The pMC value for the Aso-3 sample increased with the increasing amount of Sulfix reagent used (Figure 3), indicating that the Sulfix reagent itself can be the origin of MC contamination. This result is consistent with the study performed by Zazzo et al. (Reference Zazzo, Lebon, Chiotti, Comby, Delqué-Količ, Nespoulet and Reiche2013), who reported that the pMC values measured for the IAEA-C1 sample with Sulfix treatment were higher (i.e., more contaminated with MC) than those without Sulfix treatment. Furthermore, the 14C age estimated with the Sulfix (∼500 mg) treatment could be younger by 8000 yr than that without the Sulfix treatment for calcined bone samples of an expected 14C age of more than 32,000 yr BP.

Figure 3. pMC values obtained for the Aso-3 sample with different amounts of Sulfix reagent in the Sulfix methods.

Generally, the Sulfix method requires an additional sample preparation process because Sulfix treatment is applied to CO2 after purification and conducted at a reaction temperature lower than the sample combustion temperature (Minami et al. Reference Minami, Miyata and Nakamura2011; Nakajima et al. Reference Nakajima, Wada, Matsuzaki and Suzuki2004). This study evaluated its potential applicability using a single-step procedure for the Sulfix method, where Sulfix treatment was applied to CO2 before purification at the combustion temperature. The single-step Sulfix method can form graphite (it was not for S-containing soil samples but for the charred wood sample) but represented a moderately high level of MC contamination (pMC value: 0.55%) compared with the general (i.e., two-step procedure) Sulfix methods (Figure 1). Thus, this result indicates that C-containing impurities were liberated from the Sulfix reagent at a high combustion temperature (850°C) and became a source of MC contamination during sample preparation. However, the contamination level was similar to that of the single-step Ag foil methods with decontamination pretreatments for Ag foil.

It was interesting to observe that the MC contamination from the Ag wire method was less than or comparable to that from the Ag foil methods (Figure 1), even though no pretreatment was applied to the Ag wire. The reason for the difference in the contamination level between the two is unclear; however, it might be due to the difference in the total surface area between Ag foil (2.5 cm2) and Ag wire (0.16 cm2) used in the methods. Another reason could be due to the difference in the storage conditions between the reagents: Ag wire was stored in a small gas-tight container until use, whereas Ag foil was stored in a desiccator.

3.3. Implications for 14C dating to study carbon cycling in terrestrial ecosystems

The effect of MC contamination during sample preparation on the AMS-14C measurement can potentially be excluded by applying a straightforward blank correction when the contamination is assumed to be constant depending on the preparation method (i.e., preparing a blank sample in the same way as the target sample and subtracting the 14C activity value of the blank sample from that of the target sample) (Hua et al. Reference Hua, Zoppi, Williams and Smith2004; Mueller and Muzikar Reference Mueller and Muzikar2002). This is because sample preparation (i.e., combustion of the sample, in particular) is a major source of MC contamination throughout the entire processes of AMS-14C measurement (Schleicher et al. Reference Schleicher, Grootes, Nadeau and Schoon1998; Vandeputte et al. Reference Vandeputte, Moens, Dams and van der Plicht1998; Vogel et al. Reference Vogel, Nelson and Southon1987). However, the reliability and accuracy of the 14C dating still rely on minimizing the MC contamination during sample preparation, especially for small and old (14C-depleted) samples (Rethemeyer et al. Reference Rethemeyer, Fülöp, Höfle, Wacker, Heinze, Hajdas, Patt, König, Stapper and Dewald2013; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Meyer, Dolman, Winterfeld, Hefter, Dummann, McIntyre, Montluçon, Haghipour, Wacker, Gentz, van der Voort, Eglinton and Mollenhauer2020; Vandeputte et al. Reference Vandeputte, Moens, Dams and van der Plicht1998).

This study’s results demonstrate that the two-step procedure is a useful way to reduce MC contamination during sample preparation for both the Ag foil and Sulfix methods. The 14C age of the soil (SOC) samples of primary interest in studying the interactions between the C cycle and climate change is typically younger than 12,000 yr BP (e.g., Balesdent et al. Reference Balesdent, Basile-Doelsch, Chadoeuf, Cornu, Derrien, Fekiacova and Hatté2018; Koarashi et al. Reference Koarashi, Atarashi-Andoh, Ishizuka, Miura, Saito and Hirai2009; Luo et al. Reference Luo, Wang and Wang2019; Shi et al. Reference Shi, Allison, He, Levine, Hoyt, Beem-Miller, Zhu, Wieder, Trumbore and Randerson2020). The two-step procedure in the preparation methods is time-consuming and labor-intensive compared with the single-step procedure. Therefore, we conclude that if the straightforward blank correction is conducted, any method examined in this study can be applied to 14C dating with sufficient accuracy to study SOC cycling in terrestrial ecosystems. This conclusion is consistent with the recent finding of Olsen et al. (Reference Olsen, Daróczi and Kanstrup2023), who showed that the effect of the Sulfix method on the 14C age is small and generally within the measurement uncertainties for cremated bone samples with an estimated 14C age of approximately 3000 yr BP. However, there has been an increasing demand for 14C dating of small samples, such as a minor fraction and specific compound of SOC, with the advancement of the research field of biogeochemical cycles (Koarashi et al. Reference Koarashi, Hockaday, Masiello and Trumbore2012; Kuzyakov et al. Reference Kuzyakov, Bogomolova and Glaser2014; Nakanishi et al. Reference Nakanishi, Atarashi-Andoh, Koarashi, Saito-Kokubu and Hirai2012; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Meyer, Dolman, Winterfeld, Hefter, Dummann, McIntyre, Montluçon, Haghipour, Wacker, Gentz, van der Voort, Eglinton and Mollenhauer2020; Wijesinghe et al. Reference Wijesinghe, Koarashi, Atarashi-Andoh, Saito-Kokubu, Yamaguchi, Sase, Hosono, Inoue, Mori and Hiradate2020). For such small and old samples, it is recommended to use the two-step procedure for the preparation of AMS-14C measurements. It has also been documented that C-containing impurities associated with CuO and Fe powder, which are widely used as oxidizing agent for organic materials and catalyst for graphitization, respectively, and are also used in the methods assessed in this study, are the primary contributors to MC contamination in AMS-14C measurements (Vandeputte et al. Reference Vandeputte, Moens, Dams and van der Plicht1998). Therefore, continuous efforts for the overall blank assessment and reduction in the AMS-14C measurement are needed to improve the reliability and accuracy of 14C dating and promote the application of 14C dating to climate change science.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2024.137

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Makiko Ishihara of the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) and Tomohiro Nishio, Yoshio Ohwaki, Akihiro Matsubara, Katsuki Sanada, and Motohisa Kato of PESCO Co., Ltd. for the support with the laboratory work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (grant numbers 23380096, 15H04523).

Credit authorship contribution statement

Jun Koarashi: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition. Erina Takeuchi: conceptualization, methodology, investigation. Yoko Saito-Kokubu: conceptualization, methodology, investigation. Mariko Atarashi-Andoh: methodology, investigation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.