Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has exacerbated the risks of negative psychological and physical outcomes (anxiety, depression, poor sleep quality, loss of mobility, decline in health, etc.) as well as the social isolation of older adults in situations of vulnerability and their caregivers (Douglas, Katikireddi, Taulbut, McKee, & McCartney, Reference Douglas, Katikireddi, Taulbut, McKee and McCartney2020; Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ), 2020; Wister & Speechley, Reference Wister and Speechley2020). These risks were particularly important during the lockdown period, but also more widely throughout the pandemic. Physical distancing measures and social restrictions (e.g., visits to older adults living in residential care facilities) reduced access to health, social, and community services, and underuse of these services for fear of contamination created significant challenges for these older adults in meeting their basic needs and maintaining meaningful social interactions that promote their well-being and quality of life (Douglas et al., Reference Douglas, Katikireddi, Taulbut, McKee and McCartney2020; INSPQ, 2020; Wister & Speechley). A pan-Canadian survey conducted between April and July 2020 indicated that nearly one third of older adults in situations of vulnerability could not get help right away, if needed (Canadian Red Cross, 2020). About one third of respondents also reported feeling lonely often or every day (Canadian Red Cross). Older adults in a situation of isolation are at increased risk of experiencing abuse or mistreatment (Beaulieu, Cadieux Genesse, & St-Martin, Reference Beaulieu, Cadieux Genesse and St-Martin2020; Beaulieu, Leboeuf, & Pelletier, Reference Beaulieu, Leboeuf, Pelletier, Laforest, Bouchard and Maurice2018). These situations particularly affect more vulnerable groups of older adults, including people living alone, family caregivers, those in precarious financial situations, without access to communication technologies, and people with pre-existing mental or physical health conditions or experiencing other types of marginalization (Douglas et al., Reference Douglas, Katikireddi, Taulbut, McKee and McCartney2020; INSPQ, 2020; Mesa Vieira, Franco, Gómez, & Abel, Reference Mesa Vieira, Franco, Gómez Restrepo and Abel2020). It is therefore important to take action with key stakeholders from various sectors (such as health and social services, community organizations, private organizations, municipalities, provincial government, and citizens groups), in partnership with older adults and their families, in order to implement effective practices that address individual and community needs during the pandemic and beyond.

Jopling (Reference Jopling2015) emphasizes the fundamental role of community services in reaching people in a situation of isolation and understanding their needs in order to direct them to the appropriate resources. This is particularly important during a pandemic when older adults in a situation of isolation may be reluctant to seek the help required or to use available services for fear of contamination (INSPQ, 2020). In this context, community organizations, whose actions are initiated for, by, and with older adults in their local communities, can play a key role in connecting with older persons in situations of vulnerability and building a relationship of trust in which their needs can be communicated effectively (Bureau et al., Reference Bureau, Cardinal, Côté, Gagnon, Maurice and Paquet2017). By addressing the essential needs of older adults in vulnerable situations and their caregivers (e.g., nutrition, transportation, home support, respite care, opportunities for social participation, promotion of well-treatment), community organizations contribute to the physical and psychological well-being of many older adults. Their work in collaboration with other stakeholders from the public and private sectors enables them to act on both the individual level (such as identifying older adults at increased risk of vulnerability through phone calls or in-person visits, providing support services, and offering activities that foster socialization and personal empowerment) and the community level, by defending older adults’ rights and promoting social cohesion and resilience across communities (Bureau et al., Reference Bureau, Cardinal, Côté, Gagnon, Maurice and Paquet2017; INSPQ, 2020; Jopling, Reference Jopling2015). Therefore, these organizations are essential partners in this collective reflection and response to the COVID-19 pandemic (INSPQ, 2020).

In the context of a pandemic and particularly during a lockdown, these organizations may experience significant challenges in maintaining their services and their roles as an anchor and connection point for older adults in situations of vulnerability. A survey conducted in April 2020 involving 1,003 community organizations serving older adults in the United States highlighted various changes in the provision of support services to older adults (National Council on Aging, 2020). Although a large majority of community organizations (90%) reported that they had been able to maintain some services during the pandemic, the average number of older adult clients served decreased by 27%, suggesting that community-based organizations had less capacity to provide support services (National Council on Aging, 2020). Encouragingly, however, emerging evidence also indicates that many community organizations are innovating and showing resilience as they transition some support programs to online delivery and develop new programs or services in response to emerging needs, such as an increase in home-delivered meals and friendly phone calls (INSPQ, 2020; Meisner et al., Reference Meisner, Boscart, Gaudreau, Stolee, Ebert and Heyer2020; Mutschler, Junaid, & McShane, Reference Mutschler, Junaid and McShane2021; National Council on Aging, 2020; Smith, Steinman, & Casey, Reference Smith, Steinman and Casey2020).

In order to develop tailored solutions that address the specific needs of older adults in situations of vulnerability and caregivers during a pandemic and beyond, it is essential to gain further insight into the experiences of community organizations working with these populations. The early experiences and strategies adopted by community organizations in Quebec may be of particular interest, since this province was significantly impacted by COVID-19 in the first weeks of the pandemic, registering approximately half of the COVID-19 cases in Canada as of May 2020 (Government of Canada, 2021). In the province of Quebec, the lockdown period extended from approximately mid-March 2020 to June 2020 (INSPQ, 2021). Given this situation, how did these community organizations manage to play their roles while respecting physical distancing measures? How did they identify and support isolated older adults at increased risk of physical and psychological vulnerability, marginalization, or abuse? A greater understanding of the lessons learned and the strategies developed by community organizations in response to the COVID-19 pandemic is essential to inform the development and implementation of sustainable programs and services to improve community-based supports for older Canadians in the future. This is also consistent with a salutogenic approach, building on the strengths and solutions emerging from local organizations to foster individual and community resilience during a pandemic (Wister & Speechley, Reference Wister and Speechley2020).

Objectives

With a view to supporting community organizations’ capacity for action during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond, the objectives of this study were to 1) document the provision of services and the issues experienced by community organizations supporting older adults and caregivers in the province of Quebec during the COVID-19 pandemic, and 2) identify promising strategies they used to deliver services in this unique context, as well as strategies that might be considered in the future. More specifically, the study addressed the questions: 1) To what extent did community organizations maintain services for older adults and caregivers in times of physical distancing and during the provincial lockdown?; 2) What were the key issues and challenges experienced by community organizations in this context?; and 3) Which strategies may be implemented to adapt the provision of support services to older adults and caregivers in times of physical distancing?

Methods

Study Design

A cross-sectional electronic survey using open- (qualitative) and closed-ended (quantitative) questions was conducted in July 2020 among community organizations providing support services to older adults and caregivers across the province of Quebec. The electronic survey methodology followed the CHERRIES standards for reporting results of Internet surveys, which include the following categories: “design,” “institutional review board approval and informed consent,” “development and pretesting,” “recruitment,” “survey administration,” “response rates,” “preventing multiple entries from the same individual,” and “analysis” (Eysenbach, Reference Eysenbach2004). The study protocol was approved by the university at which the research was conducted (CER-20-267-07.09).

Study Population

Representatives of community organizations providing services to older adults and caregivers in the province of Quebec were identified from different sources, including: 1) comprehensive online directories of community-based, non-profit organizations (Information and Referral Centre of Greater Montréal, 2019); 2) lists of community-based organizations available on the websites of regional county municipalities across the province; 3) a comprehensive resource directory for caregivers (L’Appui pour les proches aidants, 2020) listing community-based resources available by region; and 4) lists of all volunteer action centres, FADOQ clubs (i.e., a network that brings together people ages 50 and over to defend their rights, to promote their contributions to society, and to provide support programs, services, and activities fostering their quality of life [Réseau FADOQ, 2021]), and community centres for older adults in Quebec. To be included, a community organization had to provide services to older adults or their caregivers in the province of Quebec, Canada, according to information on their website or in the online directories (i.e., types of services provided, targeted population, and eligibility criteria).

Participants from these organizations were eligible to complete the survey if they 1) worked as a manager, coordinator, employee or volunteer in a community organization providing support services to older adults and caregivers in the province of Quebec; 2) had worked in that organization since the beginning of the pandemic; and 3) were able to read French. No exclusion criteria were applied.

Sample Size Considerations

Sample size was based on the calculation for a single proportion (prevalence) using an assumption that at least 60% of the community organizations’ representatives would report that they maintained or adapted some services for older adults or caregivers during the pandemic. Using a confidence interval of 95% and a margin of error set at 5%, approximately 303 respondents were required to obtain stable estimates of prevalence.

Sampling and Data Collection Procedures

Using the different sources described previously, two team members (VS and MN) performed a preliminary screening to identify potentially eligible non-profit community organizations providing support services to older adults or caregivers. When there were uncertainties about the eligibility of a given organization, it was discussed with a second team member (VS or MN) and, if necessary, with a third team member (VP) to reach a consensus on the final selection. The list of eligible non-profit community organizations and their contact information (e-mail and phone number, when available) was compiled in an Excel spreadsheet, organized by region. To identify and eliminate duplicate records, the names of the organizations, their e-mail addresses, and their phone numbers were compared. The final survey frame consisted of 1,688 community organizations, 1,278 of which had a current e-mail address.

An initial e-mail invitation to complete this open survey was sent on June 30, 2020. The e-mail explained the study objectives and participation procedures, with a weblink to the informed consent form and electronic questionnaire. Two reminders were sent one and two weeks later. In addition, personalized e-mails and phone calls were made to representatives of larger regional and provincial organizations (e.g., Appui national [Caregiver Support], Tables de concertation des aînés [i.e., Issue Table for older adults] [n = 23]) to explain the study and invite them to share the survey link via their local networks and social media. The survey was also announced on a Facebook community with more than 400 members, the majority of whom were managers and workers from community organizations (Dumas, Carbonneau, Bickerstaff, & Joanisse, Reference Dumas, Carbonneau, Bickerstaff and Joanisse2020). Finally, to reach other community organizations whose e-mail addresses were not available, two trained team members (VS and MN) made additional phone calls to more than 152 organizations across all regions of the province.

The electronic survey took approximately 20 to 30 minutes to complete. Participants were invited to contact the research team if they needed assistance with filling out the survey. Data were collected from June 30 to September 6, 2020.

Questionnaire Development and Content

The electronic questionnaire was developed by an interdisciplinary team of nine researchers in gerontology, with complementary expertise related to social participation, inclusion, and community supports for older adults in situations of vulnerability, caregiving, risk management, home care and social services, mental health, leisure, community volunteering, partnership, ageism, and elder abuse. The questionnaire content was based on 1) existing resource directories (Information and Referral Centre of Greater Montréal, 2019) describing various categories of community services for older adults and caregivers (e.g., home support, transportation, respite care, intergenerational activities); 2) available scientific evidence on potential challenges and solutions for delivering community services in a pandemic; 3) some initial experiences and practices shared by community organizations in a virtual community during the lockdown (Dumas et al., Reference Dumas, Carbonneau, Bickerstaff and Joanisse2020); and 4) input from the nine interdisciplinary researchers working in collaboration with a variety of community organizations in different sectors.

The first portion of the survey consisted of eight socio-demographic questions describing the participants (including age, gender, work experience in community organizations, region served by the community organization). Next, a series of closed- and open-ended questions (see Appendix 1) was designed to document the services provided by community organizations, key issues experienced, and strategies to adapt the provision of support services to older adults and caregivers in times of physical distancing, particularly during a lockdown. More specifically, participants rated the extent to which their organization had maintained various community services on a 4-point scale (“fully,” “mostly,” “minimally,” “not at all”). They could also indicate whether each category of services was not provided by their organization (i.e., not applicable). Then they reported on key issues with providing services during the lockdown. For each of 10 categories of issues (such as managing risks to service users’ health, recruiting volunteers; see Appendix 1), they rated how difficult they were for their organization on a 4-point scale (“extremely,” “very,” “slightly,” “not at all”). Next, in an open-ended question, they were asked to provide concrete examples of solutions and promising practices they used to adapt their services. Participants also specified whether they used technology to adapt the provision of support services. Finally, in the last section of the survey, they chose three priorities (from a list of 10 categories) for improving the provision of support services to older adults in the coming year, and indicated what type of support or resources they would need to pursue these priorities.

To determine the clarity of the questions and response scales and the usability of the survey platform, the electronic questionnaire was pretested with two respondents who had extensive experience working in community organizations. Their comments led to minor revisions to clarify the wording of some questions. Before fielding the questionnaire, it was tested again with three team members to confirm its technical functionality.

Data Analysis

Survey responses were automatically entered into a database stored on a secure web-based platform at the university where the study was conducted. Quantitative data were exported into a Microsoft Excel worksheet and into the R software (R Core Team, 2020) for further analysis. One team member (VS) verified the data entries with the users’ IDs to eliminate any irrelevant responses or duplicates before performing the data analysis. Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages, means and standard deviations [SD]) were calculated for the socio-demographic variables and the quantitative responses to the closed-ended questions. Then, to compare the data by region, participants were grouped into one of three categories of regions, based on the proportions of rural and urban areas within these regions: 1) mostly urban (i.e., Montréal, Montérégie, Capitale-Nationale, Outaouais, Laval); 2) mostly rural (i.e., Abitibi-Témiscamingue, Côte-Nord, Nord-du-Québec, Gaspésie-Îles-de-la-Madeleine, Bas-Saint-Laurent); and 3) a combination of rural and urban areas (i.e., Estrie, Saguenay-Lac-St-Jean, Mauricie, Laurentides, Chaudière-Appalaches, Centre-du-Québec, Lanaudière) (INSPQ, 2019). Urban areas are composed of municipalities with very strong links to an urban core (including census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations), whereas rural areas have weaker or no links to an urban core (INSPQ, 2019). For each quantitative variable (i.e., the variables shown in Tables 1, 2, 3, and 5), scores were compared across the three categories of regions by calculating the effect size measured by the rankFD function (pd statistic) (Konietschke, Friedrich, Brunner, & Pauly, Reference Konietschke, Friedrich, Brunner and Pauly2019). The rankFD analysis of variance (ANOVA) is similar to the Kruskal-Wallis test, but it has the advantage of producing an effect size (pd statistic) based on the "probability of being greater than," thus an effect size that does not require an unrealistic metric here. This statistic is interpreted as 1) pd values are equal to 0.5 if the scores are equal across all categories of regions; 2) pd values greater than 0.5 indicate that higher values of the dependent variable are more often associated with these categories of regions; and 3) pd values less than 0.5 indicate that smaller values of the dependent variable are more often associated with these regions. To determine the size of the differences, the scale (A12) from Vargha and Delaney (Reference Vargha and Delaney2000, p. 106) is used. According to this scale, a difference can be considered small, medium, or large if 1) the pd values are greater than or equal to .56, .64, and .71, respectively; or 2) the pd values are less than or equal to .44, .36, or .29, respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of survey respondents (n = 307)

* The participants’ average age was higher for those living in rural areas (mean = 59.1 ± 14.1), as compared to urban areas (mean = 51.3 ± 14.0) and urban/rural areas (mean = 53.4 ± 14.4) (p = 0.006).

** Their average years of experience in community organizations were higher for those living in rural areas (mean = 15.8 ± 12.8), as compared to urban areas (mean = 10.1 ± 8.0) and urban/rural areas (mean = 10.2 ± 8.8) (p = 0.021).

*** Their average years of experience in their current organization were higher for those living in rural areas (mean = 11.8 ± 10.0), as compared to urban areas (mean = 6.4 ± 5.7) and urban/rural areas (mean = 7.2 ± 7.8) (p = 0.001).

† Some respondents had more than one role.

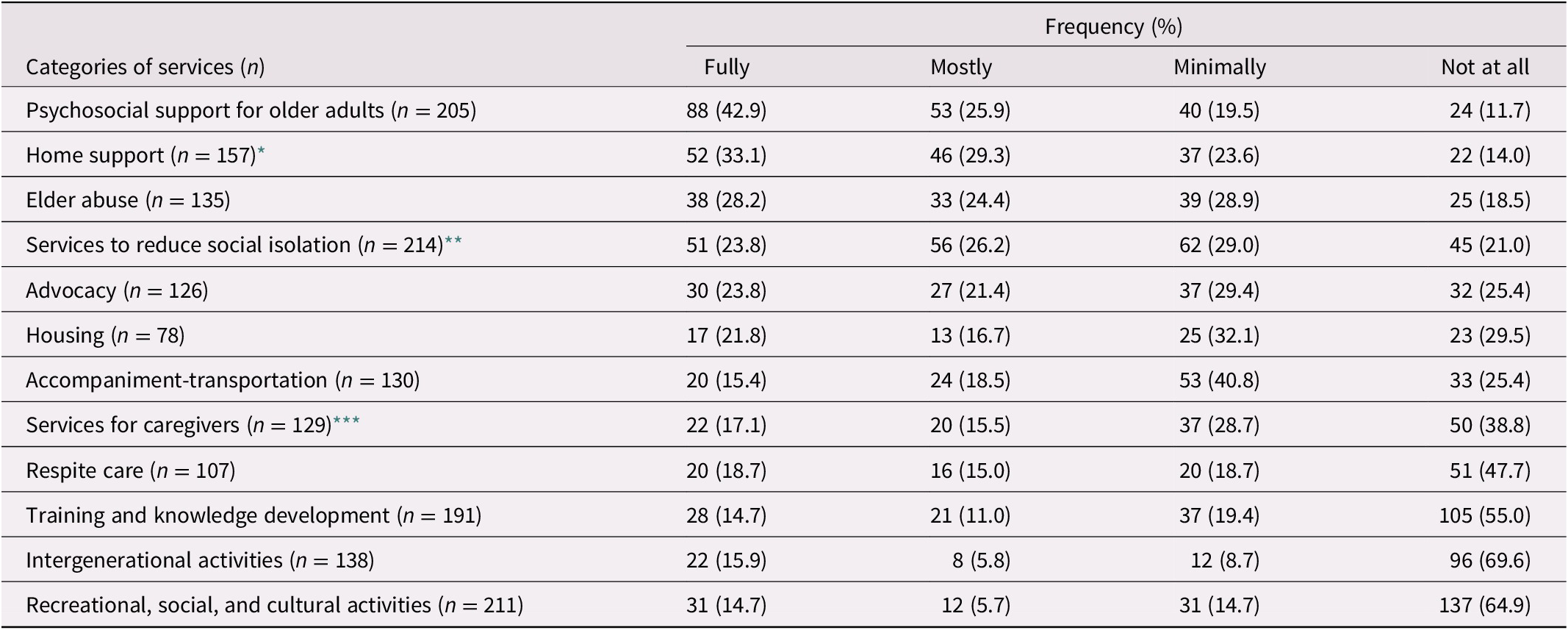

Table 2. Services maintained by community organizations during the provincial lockdown (n = 307)

* Home support services were fully or mostly maintained most often in urban regions (77.3%) than in urban/rural regions (50.0%) and rural regions (47.8%) (p = 0.003; pd = 0.38).

** Services to reduce social isolation were fully or mostly maintained most often in urban regions (53.9%) than in urban/rural regions (43.3%) and rural regions (36.0%) (p = 0.013; pd = 0.40).

*** Services for caregivers were maintained less often in rural regions (11.1%) than in urban regions (31.7%) and urban/rural regions (34.9%) (p = 0.004; pd = 0.63).

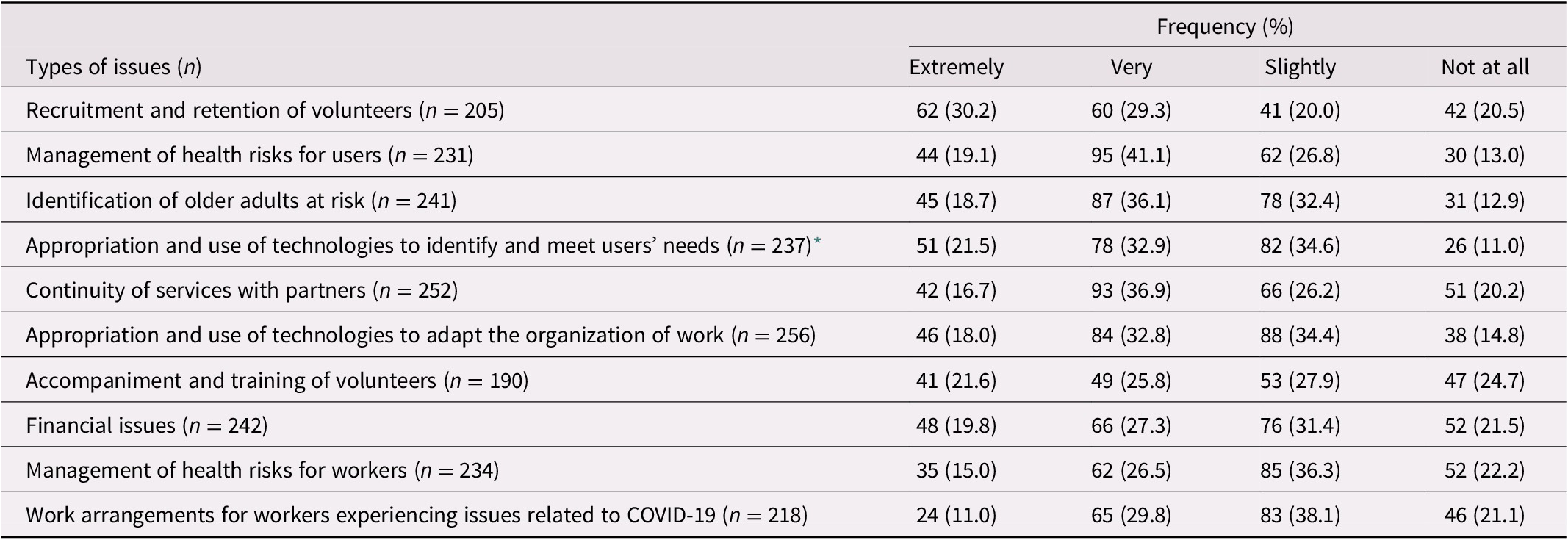

Table 3. Key issues experienced by community organizations in providing services (n = 307)

* The percentages of participants reporting extremely or very difficult issues with the use of technologies to identify and meet users’ needs were 29.6%, 53.1%, and 59.7% for rural, urban, and urban/rural regions, respectively. Participants living in rural regions tended to report fewer issues (p = 0.014; pd = 0.59).

For the open-ended questions, the participants’ responses were exported into NVivo 12 (QRS International, Doncaster, VIC, Australia) to facilitate data management and organization. Qualitative data were thematically analysed through an inductive and iterative process (Paillé & Mucchielli, Reference Paillé and Mucchielli2016). This analysis followed a series of steps. Two team members (VP and MN) read the open-ended responses to become familiar with the data set. Then, they met to establish a preliminary list of emerging themes to be included in the initial coding scheme. One team member with prior experience with qualitative data analysis (MN) coded one third of the data set, using this preliminary coding scheme while also refining and adding new codes during this coding process. Another experienced researcher (VP) independently coded approximately 10% of this data set. A meeting was held where the results of this intercoder reliability process were compared and a refined version of the coding scheme was agreed upon. Using this refined coding scheme, MN coded another portion of the data set (approximately one third) while VP also independently coded a subset (approximately 10%) of the data. Interrater agreement in the qualitative data coding between the two coders reached 93.2%. Disagreements in data coding were resolved through discussion between the reviewers until a consensus was reached. To enhance the validity of this process, a third team member (VProvencher) was also involved in the following team discussions about the themes and data interpretation. Afterwards, MN coded the remaining data. To further validate the interpretation of the findings, the final analysis was submitted to the other co-authors.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of the 370 persons who agreed to participate by providing informed consent, 307 completed at least some of the socio-demographic questions as well as questions on the provision of support services during the pandemic. Considering that 1,430 community organizations were contacted to participate in the survey (by e-mail, n = 1,278; by telephone, n = 152), the estimated participation rate was 21.5%.

The participants worked in a variety of community organizations covering all 17 regions of the province, with a greater proportion of organizations located in urban areas (45.9%) as compared to rural areas (15.1%) or urban/rural areas (39.0%) (see Table 1). The sample appeared broadly representative of the initial survey frame in terms of the proportions of community organizations from urban, rural, and urban/rural regions (i.e., 46.5%, 17.7%, and 36.0%, respectively). Comparisons of the participants’ characteristics across the three categories of regions indicated that their average age and years of work experience in community organizations and their current organization were significantly higher for those living in rural regions (p = 0.021-0.001; pd = 0.58 to 0.61, indicating small to medium differences).

Provision of Support Services to Older Adults and Caregivers During the Provincial Lockdown

Almost three-quarters of respondents (71.4%) reported having maintained services at least partially throughout the lockdown, and the majority (85.3%) adapted their services. Most participants (84.3%) reported that they used some type of technology to adapt the provision of their services during the pandemic, but they also implemented other strategies, as further explained in the section, Strategies to Adapt the Provision of Support Services.

Among the services that were fully or mostly maintained most often were psychosocial support (68.8%) and home support (62.4%) (see Table 2). Comparisons of the data across the three categories of regions indicated that home support and community services to reduce social isolation were maintained most often in urban regions (p = 0.013-0.003; pd = 0.38 to 0.40, suggesting small to medium differences), whereas services for caregivers were maintained less often in rural regions (p = 0.004; pd = 0.632, indicating medium differences). No significant differences were found for other types of services.

Key Issues Experienced by Community Organizations

Among key issues experienced by community organizations during the provincial lockdown (see Table 3), participants reported difficulties with identifying and supporting older adults at greater risk of isolation or vulnerability (those indicating that this was extremely or very difficult: 54.8%) while also managing health risks for service users (60.2%), recruiting and maintaining the engagement of volunteers (59.5%), accessing and fostering the appropriation of technologies to meet service users’ needs (54.4%), and ensuring the continuity of services with partners (53.6%). Extremely or very difficult issues were reported by at least 40 per cent of respondents for each of the categories shown in Table 3. Comparisons of the data across the three types of regions suggested that the participants from rural regions reported fewer issues with the use of technologies to meet users’ needs (p = 0.014; pd = 0.59, indicating small to medium differences). No significant differences were found for other types of issues.

Strategies to Adapt the Provision of Support Services to Older Adults and Caregivers

Community organizations reported that they used various strategies to meet older adults’ and caregivers’ needs, and to foster organizational and community resilience during the pandemic (see Figure 1). The themes identified from the qualitative data include 1) strategies for reaching out to older adults and understanding their needs; 2) direct interventions that could be adapted to support older adults; 3) implementation of prevention and protection measures; 4) access to and use of technologies; 5) human resources management; 6) financial support of the organization; 7) development and consolidation of intersectoral partnerships; and 8) promotion of a positive view of older adults (see Table 4).

Table 4. Themes and sub-themes relating to the community organizations’ strategies to adapt the provision of support services to older adults and caregivers during the pandemic

Figure 1. Strategies to adapt the provision of support services to older adults and caregivers.

Note: Community organizations used various strategies aimed at 1) meeting older adults’ and caregivers’ needs; 2) fostering their organization’s resilience; and, ultimately, 3) promoting community resilience during the pandemic. Their services were adapted by using technological solutions, implementing prevention and protection measures, or using a combination of these strategies.

Strategies to Reach Out to Older Adults and Understand Their Needs

Strategies used to reach out to older adults and understand their needs in the context of the pandemic related to three themes: 1) disseminating information about services; 2) consulting with older adults about their perceived needs; and 3) identifying and reaching out to older adults at greater risk of vulnerability.

Many community organizations were concerned with effectively communicating information about the availability of their services during the lockdown. They implemented a combination of communication methods adapted to their different clienteles, including via electronic media (i.e., e-mails, social networks, videos, radio) and through newspapers, regular mail, or in-person deliveries, as explained by one participant:

We also need to go back to paper-based communication to reach vulnerable people who don’t have access to technology. We decided to publish an Express Bulletin every two weeks and distribute it to the older adults living in the social housing where we work. (P48, urban)

To prioritize services, some also sought older adults’ views, either during friendly calls to verify their immediate and medium-term needs as well as to accompany them and direct them to the right resources (P140, urban/rural), or through surveys: At the beginning of the pandemic, we created a survey that we used to call over 800 people to determine what their needs were (P137, urban/rural).

A lot of effort was invested in identifying and reaching out to groups of older adults at greater risk of vulnerability and social isolation. These initiatives included systematic e-mails and calls to identify at-risk older adults (e.g., people living in seniors’ homes affected by COVID-19 or receiving essential services before the pandemic); delivery of free meals to identify older adults in need (P295, urban/rural); presence of outreach workers to facilitate screening, such as when our outreach team took over our Meals on Wheels deliveries to keep an eye on our older adults (P19, urban); and involvement of older adults to exercise mutual vigilance: We encouraged our older adults to keep an eye on each other (P19, urban). In-depth knowledge of clients and strong therapeutic ties with them facilitated the identification and screening of people at greater risk of vulnerability.

Direct Interventions That Could Be Adapted to Support Older Adults in a Pandemic Context

Direct interventions that were adapted and delivered by the community organizations to support older adults included 1) interventions aimed at translating and explaining sanitary and health measures; 2) essential services to meet basic needs, including mostly food-related services, transportation and accompaniment to appointments, and home support; 3) activities promoting social ties and well-being; and 4) psychosocial support and management of abuse/mistreatment situations. These services were adapted by using technological solutions, implementing prevention and protection measures, or using a combination of these strategies, depending on the type of services and the internal and external resources available to the community organization, as illustrated in Figure 1.

To provide education about sanitary and health measures, community organizations used a variety of methods (posters, videos, etc.) tailored to different populations of older adults, including translating public health information for various organizations into the language of the cultural community (P38, region not reported). This was also intended to reassure clients about the measures being implemented to ensure their safety during service delivery.

Among services addressing older adults’ basic needs, food-related services saw a marked increase in demand and organizations quickly adapted to meet this growing demand in a variety of ways: We were able to maintain all Meals on Wheels deliveries, and even serve new elderly clients who were confined to their homes (P295, urban/rural); We were able to expand the territories for the delivery of frozen meals to give as many people as possible access to this service (P163, urban). To ensure safety, they developed contactless delivery procedures, such as leaving things in a cooler placed outside or using a drive-through service, as well as new payment procedures whereby clients receive a bill at the end of the month to pay for their shopping so they don’t have to give the money to the volunteer (P64, urban). Appointment accompaniment services were also adapted to meet sanitary standards, but some organizations still had to prioritize essential services for a period of time. Other services were added with a view to reducing health risks for older adults with disabilities, such as the implementation of 1-to-1 monitoring for cognitively decompensating older adults to avoid the risk of sending them into a hot zone while waiting to find or get into a place that was suitable for their condition (P9, urban).

In comparison, psychosocial support services and interventions promoting social connections and well-being relied more on the use of technologies. Community organizations implemented a large number of activities aimed at maintaining social ties and recreational options: online (e.g., caregiver support groups); on the phone, such as creation of a new service (caring calls) to contact our users and volunteers aged 70 and over (P27, urban); delivery of materials (recreational materials, activities on CD); correspondence by mail (e.g., sending pleasant letters); and visiting in person while respecting sanitary measures. Some also developed initiatives to engage older adults and encourage mutual support (e.g., cascading calls, helpline). Organizations largely maintained or even increased psychosocial support services, mainly delivered by phone: Screening and psychosocial monitoring of 100% of our clients according to needs and increase in phone psychosocial support (P146, region not reported). Some also actively contributed, in collaboration with partners, to managing abuse and mistreatment situations through virtual and face-to-face meetings.

Implementation of Prevention and Protection Measures

The various measures described by participants to adapt face-to-face services to sanitary and health guidelines encompassed four themes: 1) environmental adaptations such as plexiglass in offices and cars for accompaniment-transportation (P121, urban/rural) and contact through glass (P5, rural) as well as activities respecting physical distancing, including outdoor programming for the summer, reducing the number of people in meetings (P137, urban/rural), group activities in the park (bocce, walking, yoga) (P297, urban); 2) purchase of protective equipment and its distribution to staff and clients, such as offering members a free mask with a transparent window (P140, urban/rural); 3) information and training for staff and volunteers regarding the application of health measures; and 4) verifying beforehand that users are symptom-free by calling families the day before in-home respite care to ensure that there is no one in the home with COVID symptoms (P23, urban).

Access to and Use of Technologies

Strategies involving the use of technologies were aimed at supporting older adults and their families and also fostering organizational resilience in the context of the pandemic (see Figure 1). One theme concerned adaptations and innovations to facilitate telework, such as procedures for digitizing clients’ records and accessing data remotely, maintaining contacts between staff members, and implementing new software, such as setting up a patient portal to avoid having patients come to the Coop (P59, urban) or new service delivery methods: We started tele-volunteering to deliver services to reduce people’s isolation (P66, region not reported).

Two other themes related more broadly to access of technological tools and support for their use by various users (managers, caregivers, volunteers, family members, and older adults). Excerpts describe different initiatives to promote access to technologies for staff members, older adults, and family members: Deploying the use of tablets for homecare workers (P158, rural); I also set up a project to provide a tablet for our older adults (P19, urban); and We had a donor who bought tablets equipped with SIM cards to enable family caregivers to stay in touch (P128, rural). The use of these technological solutions by older adults, caregivers, and volunteers also involved different strategies to guide and train users. Community organizations used various training activities, created user guides (such as videos and written tutorials), obtained support from resource people to guide the selection and use of technological tools, and held pre-event practices: We had a nice volunteer computer person who helped us organize our board meetings (P290, urban); and Help by phone and using a guide created by a volunteer for logging into Zoom so we could participate in caregivers’ meetings (P70, urban/rural).

Human Resources Management

Different strategies related to human resources management were used to support organizational resilience with respect to: 1) recruiting new volunteers, 2) hiring new staff, 3) staff reallocation and job modification, 4) training, and 5) support for human resources. Issues with recruiting volunteers were a commonly reported concern. Several organizations reported a significant loss of volunteers over the age of 70 who had to stay at home, which could impact service provision. They used a variety of means to recruit new volunteers under the age of 70, for example, the creation of a volunteer bank, advertisements, resources supporting recruitment, www.jebenevole.ca (provincial web platform pairing volunteer centres and non-profit organizations with potential volunteers), and Communauto (car sharing company) from a variety of sectors (municipal employees, educators and other staff on leave, students, etc.). Some also hired additional staff, particularly to adapt services to meet sanitary standards, such as the addition of a nurse trainer for three months to implement and monitor all sanitary and health measures (P158, rural). With changes in their provision of services, some community organizations moved quickly to reorganize their work: Our team showed great flexibility, child educators found themselves on the front lines of food aid while our thrift store manager took over Meals on Wheels (P19, urban). Finally, community organizations sought to support their staff in a variety of ways, particularly to allow for the co-development of solutions to problems encountered (e.g., regular videoconferences); to maintain team cohesion; to share challenging experiences, including meeting with staff for at least thirty minutes every day to vent (P71, urban); and to encourage the maintenance of commitment and motivation, even when services slowed down, as explained by one participant: We maintained a goal to ensure that volunteers remained involved and felt a sense of belonging (P5, rural).

Financial Support of the Organization

Implementing these different strategies necessitated a search for financial support, not just from government programs but also through donations and non-government funding. This funding made it possible to remunerate human resources, purchase additional equipment, and compensate for loss of income, as some participants explained: We managed to get good grants to meet important needs to ensure the continuity of our mission (P286, urban); and If private foundations hadn’t stepped up, there’s no question that services would have been disrupted (P77, urban). Despite these efforts, some have not been able to find the funding to maintain all of their programs or to hire all of the staff necessary to meet the growing demands.

Development and Consolidation of Intersectoral Partnerships

Participants noted the critical importance of partnerships in contributing to the resilience of their organizations and in identifying and implementing solutions to the needs of community-dwelling older adults. More specifically, they reported various initiatives fostering 1) consensus building, 2) communication, and 3) intersectoral collaboration with partners.

These initiatives enabled organizations to quickly adjust their services in accordance with constantly changing sanitary and health measures, to ensure cohesion between services and to share ideas to meet the needs of older adults: Establishment of the multisectoral crisis cell to work closely together proved to be very effective in avoiding duplication, targeting priorities and facilitating the adaptation process (P160, rural); In our region, COVID-19 monitoring committees provided cohesion and enabled different partners to manage the situation (P114, rural); and We also created a crisis cell with other partners in the territory to pool our ideas and develop concerted support for the community (P137, urban/rural).

To do this, community organizations put in place strategies to ensure efficient, rapid, and constant communications internally and with partners: Continuous follow-up with a pivotal person at the CLSC (local community services centre) to obtain information about government measures quickly (P26, urban).

This intersectoral collaboration helped enhance access to services for older adults in situations of isolation or vulnerability: The grocery shopping service for older adults was provided not only by volunteers but also city employees (great collaboration) (P15, urban/rural); We also partner with a cab company to respond to requests following the temporary retirement of our older drivers (P289, urban); and The communication with the CLSC (local community services centre) allowed us to continue [to provide] services for the most vulnerable people (P284, urban/rural).

Promotion of a Positive View of Older Adults to Counter Ageism

Although most of the strategies deployed by community organizations were aimed at directly supporting older adults with a variety of services, a few participants emphasized the importance of raising awareness about issues of ageism in the context of the pandemic, particularly through media campaign to talk about the impact on older adults and to decry problem situations (P111, rural) or a radio campaign on rights and freedoms during a pandemic (P188, urban/rural). Others focused on sharing and valuing the successes and accomplishments of older adults during the pandemic: We used a photo contest to highlight good work done by older adults during a lockdown (P30, urban).

Future Priorities

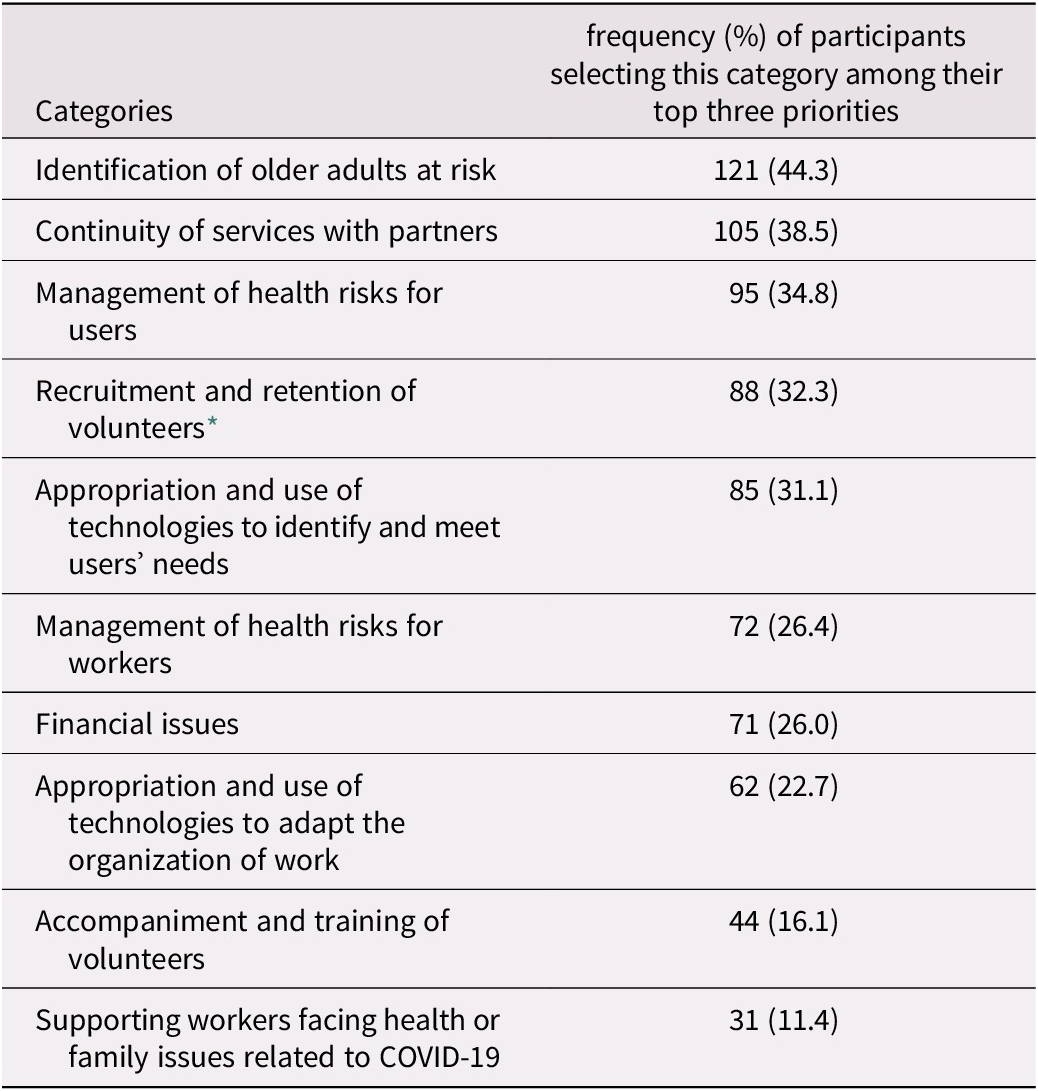

Participants’ perceived priorities for improving the provision of support services to older adults and caregivers in the next stages of the pandemic (i.e., after the lockdown is lifted or reinstated) are listed in Table 5. The three most important priorities were identifying and supporting older adults at greater risk of isolation or vulnerability (44.3%), ensuring the continuity of services with partners (38.5%), and managing health risks for service users (34.8%).

Table 5. Future priorities perceived by community organizations (n = 273)

* The recruitment and retention of volunteers were most often prioritized by participants living in urban/rural regions (51.7%), as compared to those living in urban regions (37.6%) and rural regions (29.7%) (p = 0.040; pd = 0.44, suggesting small differences).

According to the qualitative findings, a combination of strategies at the organizational, community, and societal levels is needed to support community organizations working on these priorities. These strategies relate to six themes: 1) access to ongoing funding to keep our staff employed over the long term while maintaining the adapted services (P124, urban); 2) support for recruitment and retention of human resources; 3) access to technologies, for example, obtaining tablets to rent to older adults (P203, urban) and personalized training and support for various users including managers and employees and some volunteers so that they can pass on their knowledge to older adults who are interested in learning about technological tools (P224, urban); 4) development of innovative solutions to resume some face-to-face services such as places outside the home where family caregivers can talk freely (P107, region not reported); 5) development and consolidation of intersectoral partnerships to think about and develop other forms of respite care or other ways of doing things or with other partners (P1, rural); and 6) solidarity actions that support the roles of community organizations with older adults: Collective strategies for identifying [isolated and vulnerable older adults], which go beyond the scope of each organization and create a real radar of societal monitoring of people at risk of frailty (P202, urban).

Discussion

This survey provided some useful insights into the community organizations’ early responses to COVID-19 in order to meet the needs of older adults and their caregivers across the province of Quebec. More specifically, the study described the provision of various services and the issues experienced by community organizations supporting older adults and caregivers in this context (objective 1), as well as promising strategies they used to deliver services or that might be considered in the future (objective 2).

Concerning the first objective, the results point to variations in maintaining the provision of services in different areas during the lockdown. Psychosocial and home support services for older adults seemed the least affected, with approximately two thirds of participants reporting that they fully or mostly maintained these services. According to the qualitative data, some organizations even increased their services or introduced new ones (such as food-related services) in response to pressing needs, which were also reported in a previous American survey of community organizations serving older adults (National Council on Aging, 2020). These results may suggest that services perceived as essential were prioritized at the expense of others which were interrupted more often, such as social and intergenerational activities, caregiver support services, and respite care. These findings were similar to those of a U.K.-wide survey conducted in April and May 2020 with older adults and carers, who reported significantly reduced access to various support services, particularly social activities and respite care (Giebel et al., Reference Giebel, Lord, Cooper, Shenton, Cannon and Pulford2021). Giebel et al. (Reference Giebel, Lord, Cooper, Shenton, Cannon and Pulford2021) found that the interruption of these social support services was associated with a significant decrease in well-being among the older adults and caregivers surveyed, in addition to a significant increase in anxiety among the older adults, particularly those with dementia. This highlights the importance of maintaining continuous access to these essential services even or especially during a pandemic, particularly given the potential impact of interruptions on more vulnerable and isolated older adults and caregivers (increased caregiver burden, hospitalizations, and so forth [Mattei et al., Reference Mattei, Goldoni, Mariani, Casu, Boccaletti and Ferrari2020; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Farid, Noel-Miller, Joseph, Houser and Asch2017]).

Considerations about access to support services must also take into account different regional realities. In the present survey, comparisons of service provision across urban and rural regions indicated that some types of services, including home support, services to reduce social isolation, and support for caregivers, were maintained significantly more in urban areas. Among the many factors that may account for these regional differences, the older age of survey respondents in rural areas (including managers, support workers, and volunteers delivering services) may have influenced the organizations’ decisions concerning service provision. Henning-Smith (Reference Henning-Smith2020) also suggested that older adults living in rural areas may experience the impact of COVID-19 differently, given the variations in economic and health care resources and the potential challenges related to access to technologies and online connectivity. Surprisingly, in the present study, community organizations in rural regions tended to report fewer issues with the use of technologies for delivering services to users. Perhaps community organizations in these regions relied on other strategies and community resources to deliver services. Given the potential challenges in accessing the Internet in some rural communities, some community organizations may have opted for non-technology-based solutions and, as a result, may have been less likely to report problems with technology use. A greater understanding of the experiences of community organizations providing services in rural areas, as well as factors that might explain potential regional differences, is needed in order to support their capacity for action during the pandemic and beyond.

When choosing the priorities for adapting and improving support services in the next stages of the pandemic, the survey participants in the present study highlighted the need to better identify and support older adults at greater risk of isolation or vulnerability while also managing health risks for service users as well as ensuring the continuity of services with partners. It is noteworthy that these three priorities were also some of the most important issues faced by community organizations during the lockdown, along with the recruitment and retention of volunteers, and the appropriation and use of technologies to meet users’ needs. The participants’ perceived priorities are also consistent with the COVID-19 Connectivity Paradox described by Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Steinman and Casey2020), which suggests implementing strategies that promote social interaction while balancing safety and quality of life by simultaneously mitigating the risks of isolation and infection. However, the acceptability of these risks (versus the potential perceived benefits) for clients remains to be explored (such as letting someone enter their home or sharing space with other people).

Among promising strategies that may promote social interaction and psychosocial support of older adults and caregivers, online and/or telephone interventions were introduced by many community organizations during the lockdown. Similar adaptations were also reported in a Canadian study by Mutschler et al. (Reference Mutschler, Junaid and McShane2021) conducted with 29 stakeholders from community-based organizations (Clubhouses) providing psychosocial rehabilitation services for people with mental health issues. These researchers concluded that technology-based programs might fill some of the gaps in services, such as to engage community members who cannot participate in face-to-face interventions, but should not totally replace in-person programming. Therefore, there is a need for hybrid solutions, including technological and non-technological aspects, in order to reach and support older adults and their caregivers (Seifert, Reference Seifert2020; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Charness, Fingerman, Kaye, Kim and Khurshid2020). This is particularly important since support services do not all have the same degree of adaptability to technology (e.g., respite care) or may not be accessible to older adults at greater risk of isolation, vulnerability, or marginalization (such as people with major cognitive or sensory disabilities or in precarious financial or social situations). At the same time, the participants in the present study recognized the critical need to improve older adults’ access to technological solutions (i.e., smart phones, tablets, computers) and support in using them, as well as to counter ageist stereotypes, which may exacerbate the existing digital divide (Lagacé, Charmarkeh, Zaky, & Firzly, Reference Lagacé, Charmarkeh, Zaky and Firzly2016; Sawchuk, Reference Sawchuk2016; Seifert, Reference Seifert2020). While some issues and potential solutions to counter ageism were discussed by a few of the participants surveyed, it is important to document how the situation evolves in the next stages of the pandemic.

Another key avenue is to explore the sustainability of intersectoral solutions identified in partnerships between various stakeholders. The survey data indicate that many of the solutions implemented to adapt the provision of support services, as well as solutions that might be considered in the future, involve the creation and consolidation of partnerships. Whether the objective is to facilitate the identification of older adults at risk (e.g., isolation, abuse, physical, or psychological vulnerability), to support volunteer recruitment (for in-person volunteering and virtual volunteering (Lachance, Reference Lachance2021), to identify new funding sources or to share information and training resources, the importance of partnerships was emphasized by the participants. Similarly, Richard et al. (Reference Richard, Bergeron, Lessard, Toupin, Ouellet and Bédard2021) insist on the importance of strengthening intersectoral partnerships in order to develop innovative solutions to meet the needs of older adults in situations of vulnerability, particularly in rural areas.

According to the findings of a group of community development partners in the province of Quebec (Thériault, Reference Thériault2021), the pandemic amplified pre-existing dynamics of collaboration and cooperation in communities. Those who had well-established consultation structures and communication channels and a positive view of collective action were able to use these spaces more effectively to build a concerted response to the crisis. It is therefore important to continue to value the shared successes of community stakeholders and to promote social solidarity in order to foster the resilience of individuals, community organizations, and communities.

Strengths and Limitations

Among the strengths of this study, the relatively large sample size and the diversity and representativeness of respondents from a variety of community organizations across urban and rural regions may increase the generalizability of the results. However, despite the strategies used (phone and contact network) to reach participants who may not have access to the Internet, the more overloaded or exhausted community stakeholders may not have found the time and energy to complete online or telephone surveys. Some contextual factors also need to be considered when interpreting the results. The survey data were collected during the first wave of COVID-19, immediately following a complete shutdown in the province of Quebec, which also had the highest rates of COVID-19 cases at that time. There is a need to understand how solutions arising from these data may apply in a different context and in the next stages of the pandemic, as the key issues experienced may differ. A follow-up with the community organizations to further understand their future priority issues, as well as the factors enhancing or limiting their ability to adapt and provide support services one year after the beginning of the pandemic, is currently under way.

Conclusion

The survey results highlighted key issues and innovative solutions to support community organizations in playing and strengthening their roles as an anchor and connection point for older adults in situations of vulnerability and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. With the emergence of these innovative practices, deployed in the context of the pandemic here and elsewhere in the world, some researchers and stakeholders emphasize the importance of evaluating and sustaining them so that they can be incorporated into the long-term provision of services to support older adults in situations of vulnerability or isolation (Meisner et al., Reference Meisner, Boscart, Gaudreau, Stolee, Ebert and Heyer2020; Wister & Speechley, Reference Wister and Speechley2020). To achieve this, it is important to co-create collaborative bridges and knowledge-sharing spaces between these organizations. This might be also accomplished as part of action research projects where stakeholders from various sectors are brought together. The integration of multiple perspectives may help identify relevant tools and strategies potentially transferable to other crises to minimize future health risks to older adults while preserving the benefits of human contact. At the heart of this process, older adults and their caregivers are essential partners in prioritizing and adapting services in ways that are consistent with their values, preferences (e.g., acceptability of risks to different populations), and experiences.

Acknowledgements

We thank the research participants for the time and energy they devoted to this study.

Funding

This research was supported by a COVID-19 research grant from the Quebec Network for Research on Aging/Le Réseau québécois de recherche sur le vieillissement, which is funded by the Quebec Research Fund–Health/Le Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0714980821000507.