The increasing role of cultural and morality issues in shaping political behavior and policy attitudes has resulted in a shift in how observers view contemporary American politics. Scholars have long thought that economic and class interests dominated American politics: low-income, low-education, and working-class and poor Americans support the Democratic Party and more liberal policies; middle- and upper-income, higher-education, and middle- and upper-class Americans support the Republican Party and more conservative policies (Bartels Reference Bartels2006; McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal 2006; Stonecash Reference Stonecash2000). However, the growth of contentious social issues seen as part of the “culture wars” (e.g., abortion, gay rights, school prayer, and religious freedom, among others) has spurred a debate about the relative importance of economic and cultural issues in shaping the political attitudes and behaviors of Americans (Bartels Reference Bartels2006; Frank Reference Frank2004; Hunter 1991; Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow1988).

Indeed, in his influential work, Hunter (1991) introduced the “culture wars” argument, suggesting that there is an increasingly antagonistic divide between traditionalists (i.e., those who adhere to traditional moral teachings) and progressivists (i.e., those who either support a more flexible interpretation of morality or reject traditional moral teachings altogether). Hunter suggested that these divisions go beyond mere religious denomination but rather reflect an ideological schism that divides Americans and creates political and social conflict. Hence, traditionalist Catholics, Protestants, and Jews are seen as having more in common than progressivists of the same religious traditions (Campbell Reference Campbell2006). Frank (Reference Frank2004) contended that the growing importance of cultural issues has moved some voters to abandon the socioeconomic basis for partisan attachments and policy positions, whereas others (e.g., Bartels Reference Bartels2006) suggested that class-based politics is alive and well in the United States. This scholarly debate has resulted in renewed interest in the role of cultural or morality issues in American politics (Danielsen Reference Danielsen2013; Gaines and Garand 2010; Mulligan, Grant, and Bennett Reference Mulligan, Grant and Bennett2013; Shao Reference Shao2016; Uecker and Lucke Reference Uecker and Lucke2011).

Many of the issues that contribute to the culture wars involve competing views of individual rights and the relative priority positions among these rights. For instance, pro-life advocates cast their opposition to abortion in terms of the right to life for unborn children, whereas pro-choice advocates cast their support for abortion rights in terms of the right of women to control their own bodies, particularly in the area of reproduction. Similarly, supporters of embryonic stem-cell research tout the right of individuals suffering from serious illnesses to receive the best medical treatments that medical researchers are able to develop, whereas opponents focus their attention on the right to life for human embryos. In yet another case, advocates of LGBT rights point to the right of individuals to be free from discrimination in employment and the marketplace based on sexual orientation or gender status, whereas individuals with traditional religious views contend that their First Amendment rights to the free exercise of their religion means that they need not recognize the choices of others with whom they disagree. What makes issues such as these so contentious is that they involve individuals who hold heartfelt positions about what they perceive to be the privileged position of their view of rights over the view of rights held by others.

Do individuals have a right to receive contraception services in the insurance programs provided by their employers, and can the federal government compel employers to provide such coverage? Or do employers have the right to an exemption from federal law and to deny employees contraception coverage if providing it contradicts their religious beliefs? If these two rights are in conflict, which one has priority over the other?

One of the more contentious issues in the United States in recent years is the HHS contraception mandate, which requires employers to provide contraception services to employees in the health-insurance plans that they are required to provide as part of the ACA. This mandate tests competing views of individual rights relating to the provision and receipt of contraception services. Do individuals have a right to receive contraception services in the insurance programs provided by their employers, and can the federal government compel employers to provide such coverage? Or do employers have the right to an exemption from federal law and to deny employees contraception coverage if providing such coverage contradicts their religious beliefs? If these two rights are in conflict, which one has priority over the other? It is this very conflict that was at the core of the US Supreme Court decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores (2014), in which the Court sided with the religious-freedom arguments of employers in closely held for-profit corporations.

This article considers how Americans prioritize contraception rights and religious rights by exploring the determinants of attitudes toward the HHS mandate in the American mass public. We use data from the February 2012 Political Survey from the Pew Research Center to estimate a model of support among Americans for a religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate. We focus our attention on the effects of identification with various religious traditions, religiosity, and moral conservatism because these variables would be expected to affect how many Americans think about an issue so closely tied to religious liberty. We also highlight the effects of gender because this variable would be expected to shape how many Americans think about an issue so closely tied to contraception rights for women. The clash of rights also is closely linked to various political attitudes (e.g., ideology, partisan identification, support for the Tea Party, and support for President Obama), so we also consider the effects of these variables on how Americans think about an issue so closely linked to their views about the proper role of government.

BACKGROUND

On March 23, 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law the ACA, one element of which requires employers and educational institutions to provide health insurance for their employees beginning in August 2012. This employer-based health insurance must also include contraception coverage at no additional cost to the employee. In January 2012, HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius issued regulations stating that nonprofit employers who object to contraceptive coverage due to religious beliefs had an additional year (until August 2013) to comply with the regulations of the law (Sebelius Reference Sebelius2012). Whereas churches and other houses of worship are exempt from this regulation, other nonprofit organizations affiliated with religious groups—including hospitals, universities, and charities—are not exempted and therefore are required to cover contraception and other preventative services for women at no additional cost for female employees. According to HHS, the preventative services outlined by the Institute of Medicine and cited in the HHS mandate apply only to women, although some argue that the language is unclear as to its application to male-based contraception, such as vasectomies (Appleby Reference Appleby2012).

These regulations quickly sparked heated debate and legal action. As might be expected, since the inception of the contraception mandate, religion has played a central role in the debate surrounding this issue. The Catholic Church and other religious communities have been fervent opponents of the contraception mandate. In a statement released on the same day as the HHS mandate announcement, Cardinal Timothy Dolan, President of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, called the ruling an attack on religious freedom and urged the Obama administration to overturn the HHS mandate. According to Cardinal Dolan, “to force American citizens to choose between violating their consciences and foregoing their healthcare is literally unconscionable. It is as much an attack on access to health care as on religious freedom” (US Conference of Catholic Bishops 2012).

As a point of fact, most lawsuits filed in opposition to the HHS mandate cite a violation of religious freedom as the primary complaint. In May 2012, 43 institutions—including Catholic dioceses, schools, and other organizations—filed lawsuits arguing that the mandate violates a number of federal laws that protect religious liberties, including the First Amendment and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) (Duke Reference Duke2012; Goodstein Reference Goodstein2012). Opposition goes beyond its primarily Catholic leadership. Evangelical organizations (e.g., Wheaton College), several states, and private for-profit organizations (e.g., Hobby Lobby Stores) joined lawsuits against the mandate, all citing violations of religious liberties (Cohen Reference Cohen2012; Gehrke Reference Gehrke2013; Marrapodi Reference Marrapodi2012).

In the face of this criticism, the Obama administration took strides to address the concerns of opponents of the mandate. From February 2012 to February 2013, President Obama proposed various versions of a compromise, all of which made the insurer—rather than employers—responsible for providing contraceptive coverage to women free of charge. Nonprofit religious-based institutions would still be required to provide contraceptive coverage but also would have the option to “opt out” if they believe the mandate “violates their religious sensibilities” (Bassett Reference Bassett2012; Merica and Bohn Reference Merica and Bohn2013). If an institution decided to opt out, contraceptive coverage would fall to the insurers, and employees seeking those services would receive coverage through individual health-insurance policies at no additional charge (Bassett Reference Bassett2013). In this way, individuals are covered and employers ostensibly do not have to pay for coverage of services to which they object. The final HHS mandate regarding contraceptive coverage was finalized on June 28, 2013 (Pear Reference Pear2013). The deadline of August 1, 2013, for compliance was extended until January 1, 2014 (Merica and Bohn Reference Merica and Bohn2013). Noncompliance would result in fines of $100 per day per employee.

Critics of the contraception mandate were not assuaged by the revised regulations. The debate surrounding it culminated with the decision of the US Supreme Court in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores (2014), in which the Court ruled 5–4 against the application of the contraception mandate to “closely held corporations” (e.g., Hobby Lobby Stores and Conestoga Wood Specialties) with strong religious objections. Justice Samuel Alito wrote the majority opinion, citing the RFRA—not the First Amendment—as the basis for the decision. Justice Alito contended that there is a compelling state interest in providing a full range of contraception options, but the forms of contraception deemed unacceptable on religious grounds by Hobby Lobby and others could be provided to employees through “less-restrictive means” (e.g., government provision) that do not burden their rights of free exercise of religion. In a sharply worded dissent, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg questioned the degree to which for-profit companies can exercise a religious right in refusing to provide contraception coverage, particularly because such companies employ a wide variety of people—including those who do not share the same religious beliefs.

Even in the post–Hobby Lobby period, the HHS contraception mandate continues to generate opposition from religious groups. The US Supreme Court agreed to take up the case of Little Sisters of the Poor House for the Aged v. Burwell (2015), which addressed how to accommodate the objections of religious organizations to the contraception mandate. The Obama administration offered an accommodation that permits religious organizations to opt out of the contraception mandate by certifying in writing to the government that they oppose, on religious grounds, coverage of contraceptives for their employees. Providing this certification triggers the provision of contraceptives by their insurance company at no cost to the religious organization. The Little Sisters of the Poor contended that their objections were not about the cost of providing contraception but rather are about the morality of having a health plan that provides their employees with contraceptives, including emergency contraception, to which they strenuously object on religious and moral grounds. They argued that their participation in the certification process results in the subsequent provision of contraceptives by their insurance company. Therefore, they argued, participating in the certification process makes them complicit in the provision of contraception and that this action violates their firmly held religious views (Becket Fund Reference Becket2016). Eventually, this case was consolidated with several other similar cases challenging the contraception mandate. However, in the consolidated case of Zubik v. Burwell (2016), the eight-member court issued a per curium decision remanding the case back to the lower courts with instructions to reconcile the religious-liberty interests of the plaintiffs with the rights of women employees to receive contraception coverage.

The future of the HHS contraception mandate is unclear. Whether this issue will return to the Supreme Court after the appointment of Justice Neil Gorsuch remains to be seen. If the competing parties in this case are unable to reach an agreement—a distinct possibility—it is possible that the case will return to be decided by the full Court. Moreover, the election of President Donald Trump has created considerable uncertainty about the future of the HHS contraception mandate. Candidate Trump had stated during the campaign that he would eliminate the contraception mandate, and in October 2017 HHS issued two rules providing an “exemption to any employer that objects to covering contraception services on the basis of sincerely held religious beliefs or moral convictions” (Pear, Ruiz, and Goodstein Reference Pear, Ruiz and Goodstein2017). Several states have filed challenges to the new HHS rules in federal court (McCullough Reference McCullough2017).

Clearly, the HHS contraception mandate is highly contentious, and this issue has sharply separated Americans into two groups: (1) those who support it and who believe that it should apply broadly, regardless of religious objections; and (2) those who oppose it and/or believe that there should be an exemption for those who hold strong religious convictions that are at odds with the mandate. This clash of values between these groups is explored in this article.

Clearly, the HHS contraception mandate is highly contentious, and this issue has sharply separated Americans into two groups: (1) those who support it and who believe that it should apply broadly, regardless of religious objections; and (2) those who oppose it and/or believe that there should be an exemption for those who hold strong religious convictions that are at odds with the mandate.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH

To date, we are not aware of any scholarly research that has been published on public opinion toward the HHS contraception mandate. However, there are some relevant scholarly literatures that inform our study of this topic.

Determinants of Attitudes on Social and Cultural Issues

In considering the clash of values that is inherent in the culture wars and the growing importance of social issues (including the HHS contraception mandate), it is important to consider the effects of key variables that differentiate Americans on these cultural issues. First and foremost, religion—including religious affiliations and self-identifications, strength of religious beliefs, and the content of religious beliefs—has a key role in determining how Americans think about social and cultural issues (Campbell and Monson 2008; Green et al. Reference Green, Guth, Smidt and Kellstedt1996; Hunter Reference Hunter1991; Layman Reference Layman2001; Putnam and Campbell Reference Putnam and Campbell2010; Wilcox and Norrander Reference Wilcox, Norrander, Norrander and Wilcox2002). There is an extensive literature on the role of religion in shaping attitudes on social issues; however, as Jelen (Reference Jelen, Smidt, Kellstedt and Guth2009) points out, which religion variables have an effect is subject to disagreement. Some scholars point to the effects of religious affiliation (Bolce and De Maio 1999; Brooks and Manza Reference Brooks and Manza2004; Kellstedt and Green Reference Kellstedt, Green, Leege and Kellstedt1993; Kellstedt et al. Reference Kellstedt, Green, Guth and Smidt1997; Steensland et al. Reference Steensland, Park, Regnerus, Robinson, Bradford Wilcox and Woodberry2000), whereas others focus their attention on religiosity and church attendance (Brooks and Manza Reference Brooks and Manza2004; Haider-Markel and Joslyn Reference Haider-Markel and Joslyn2005; Sullins Reference Sullins1999) or values and beliefs (Brewer Reference Brewer2003a; Reference Brewer2003b). Still other scholars note that the religion variables that may influence attitudes on social issues may not be the same that influence Americans’ attitudes toward economic issues (Gaines and Garand 2010; McCarthy et al. 2016; Wilson Reference Wilson, Smidt, Kellstedt and Guth2009). The bottom line is that there is a rich body of work connecting Americans’ attitudes toward social issues and various religion variables.

It is also the case that key political attitudes—especially partisan identification and political ideology—have a strong effect on how Americans think about social and cultural issues. Indeed, Layman (Reference Layman2001) suggests that the linkage between political ideology and partisan identification, on one hand, and attitudes toward social and cultural issues, on the other, has increased over time. Hence, the trends toward greater party polarization (Abramowitz and Saunders Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008; McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal 2006) and increased partisan–ideological sorting (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2009) seem to have magnified the connection between general political attitudes and how Americans think about social and cultural issues.

Gender also is an important potential determinant of Americans’ views toward social and cultural issues such as the HHS contraception mandate. Kaufman (Reference Kaufman2002) gives social and cultural issues a special place in shaping the gender gap in partisan identification. She shows that cultural issues—including support for reproductive rights, gender equality, and gay and lesbian rights—not only have a strong effect on partisan identification for women but also that this effect is growing over time. This suggests that cultural issues may be playing a major role in sustaining the gender gap in political behavior and attitudes. Conversely, other studies have shown that gender does not have a strong effect on Americans’ attitudes toward abortion (Barkan Reference Barkan2014; Cook, Jelen, and Wilcox 1992; Zigerell and Barker Reference Zigerell and Barker2011) and same-sex marriage (Gaines and Garand 2010). Hence, although there are plausible reasons to think that gender could be a strong determinant of attitudes toward the religious exemption to the HHS mandate, the jury is still out.

Attitudes toward Contraception Policy and the HHS Mandate

The body of research on attitudes toward contraception policy generally and the HHS mandate specifically is relatively undeveloped. Scholars have explored contraception utilization among women, but this research emphasizes determinants of individuals’ decisions to use contraception rather than individuals’ approval or disapproval of policies relating to contraception access and use (Jones, Mosher, and Daniels Reference Jones, Mosher and Daniels2012; Mosher et al. Reference Mosher, Martinez, Chandra, Abma and Wilson2004). The fact is that we know little of what Americans think about public policies designed to promote contraception use and/or to provide widespread access to contraception.

Perhaps the most noteworthy research on attitudes toward the HHS mandate is not conducted on samples drawn from the mass public but rather on a national sample of physicians. Antiel et al. (Reference Antiel, O’Donnell, Humeniuk, Carlin, Hardt and Tilburt2014) explore the determinants of physicians’ views on the contraception mandate and find that several key variables are related to support for it, including sex, region, political ideology, religious affiliation, and religious participation. Moreover, other scholars have considered the role of religion in shaping how health-care professionals address medical practices to which they have a conscientious objection, primarily as it relates to abortion, emergency contraception, and contraception (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson, Pettis, Joiner, Cook and Klugman2010; Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Rasinski, Yoon and Curlin2011; Nordstrand et al. Reference Nordstrand, Nordstrand, Nortvedt and Magelssen2013).

At this time, we know little of the determinants of how the mass public thinks about the religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate. Insights from the literature on health-care professionals suggest possible determinants of Americans’ attitudes toward this policy. At the top of the list is religion, the manifestations of which may have discernible effects on whether individuals prioritize religious-freedom rights over reproduction rights. Individuals who identify with certain religious traditions or denominations might be expected to be more supportive of a religious exemption to the contraception mandate, particularly because opposition to contraception use is part of the official teaching of some religious traditions (e.g., the Catholic Church). Alternatively, those who exhibit high levels of religiosity (perhaps through high levels of attendance at religious services) are likely to prioritize religious freedom. Political attitudes (e.g., partisanship and political ideology) also are expected to have an effect on how individuals referee debates between reproductive rights and religious freedom because these attitudes help to define how individuals perceive the role of government and the rights of individuals. Because women are the primary users of contraception and are the only ones who experience pregnancy, it also is likely that gender is a primary factor in explaining how Americans think about contraception access and government policies related to contraception and religious freedom.

MODELING ATTITUDES TOWARD THE HHS CONTRACEPTION MANDATE

To explore the determinants of individuals’ attitudes toward the HHS contraception mandate, we use data from the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, which is an independent, nonpartisan research project housed within the Pew Research Center that provides public-opinion survey data on a number of topics and policies (Pew Research Center 2012). To collect these data, telephone interviews were conducted February 8–12, 2012. Interviewers at Princeton Data Source interviewed a national sample of 1,501 adults, all 18 years or older and living in the United States. A total of 900 respondents were interviewed on a landline and 601 were interviewed on a cellphone. Potential respondents were identified using random-digit-dialing samples of landline and cellphone numbers. To achieve a representative sample of the United States, the sample was weighted according to gender, age, education, race, Hispanic origin and nativity and region. Additional weighting was based on patterns of telephone status and landline and cellphone usage.

Attitudes toward an Exemption to the Contraception Mandate

The dependent variable in our analysis relates to how individuals think about the religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate. To measure this variable, we rely on the following two survey questions asked of the respondents:

How much, if anything, have you heard about a proposed federal requirement that religiously affiliated hospitals and colleges, along with nearly all other employers, cover contraceptives in their employee health-care benefits, even if the use of contraceptives conflicts with the religious position of these institutions? Have you heard a lot, a little, or nothing at all about this?

Those who responded that they had heard “a lot” or “a little” were then asked the following question:

Should religiously affiliated institutions that object to the use of contraceptives be given an exemption from this rule, or should they be required to cover contraceptives like other employers?

This variable is coded 1 for individuals who responded that religiously affiliated institutions should be given an exemption and 0 otherwise.Footnote 1 This variable serves as the dependent variable for our statistical models.

Independent Variables

We suggest that there are several theoretically relevant clusters of independent variables that should shape individuals’ attitudes toward the HHS mandate. We focus on religion variables—religious beliefs, traditions, and levels of participation—that are likely to have an important effect on how Americans think about the religious exemption to the contraception mandate. Moreover, we suggest that the clash of values over the HHS contraception mandate will be shaped by gender and political attitudes, both of which will influence how Americans perceive competing rights claims as they relate to contraception rights and religious liberty. We also speculate that demographic and socioeconomic attributes have an effect on Americans’ views toward the HHS mandate that go beyond the effect of religious beliefs, gender, and political attitudes.

We focused on religion variables—religious beliefs, traditions, and levels of participation—that are likely to have an important effect on how Americans think about the religious exemption to the contraception mandate. Moreover, we suggest that the clash of values over the HHS contraception mandate will be shaped by gender and political attitudes, both of which will influence how Americans perceive competing rights claims as they relate to contraception rights and religious liberty.

Religious Orientation

We consider the effects of several variables that represent how Americans think about religion and morality, particularly in terms of the religious traditions to which individuals are attached, the importance of religion in their daily lives, and their adherence to traditional moral beliefs.

Religious tradition

We contend that the faith traditions with which Americans’ affiliate may shape their views toward the HHS contraception mandate. In particular, the Catholic Church has been active in its opposition to the mandate, and other religious traditions (i.e., fundamentalist Christians and Mormons) also have voiced similar opposition. Conversely, adherents to more liberal religious traditions (e.g., Jews and liberal Protestants) or secular individuals without a religious attachment have been more supportive of the mandate and should be more likely to oppose a religious exemption. Respondents were asked to identify their current religion and were given the options of Protestant, Catholic, Mormon, Orthodox, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, atheist, agnostic, something else, or nothing in particular. Roughly following the lead of Steensland et al. (Reference Steensland, Park, Regnerus, Robinson, Bradford Wilcox and Woodberry2000), we separate these religious-affiliation variables into eight separate dichotomous variables: mainline Protestant, black Protestant, white evangelical Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, Mormon, Other Christian/Orthodox, and atheist/agnostic/secular. Each variable is coded 1 for those in the respective religious group and 0 otherwise. For the three Protestant-tradition variables: (1) black Protestants are black respondents who identify as Protestant; (2) white evangelical Protestants are white Protestants who report being “born again”; and (3) mainline Protestants are nonblack Protestants who are not “born again.” We use secular respondents as the excluded (i.e., contrast) group, and we expect that each religious group would be more supportive of an exemption to the contraception mandate than secular respondents. In addition, the Pew Research Center (2012) survey includes an item indicating whether respondents considered themselves to be a “born again” or evangelical Christian. This variable is coded 1 for born-again or evangelical Christians and 0 otherwise. We expect that the coefficient for this variable would be positive, indicating that this group is more favorably oriented toward a religious exemption.

Religiosity

Religiosity is measured by frequency of attendance at religious services. Respondents were asked, “Aside from weddings and funerals, how often do you attend religious services? More than once a week, once a week, once or twice a month, a few times a year, seldom, or never?” This variable is coded to range from 0 (never) to 5 (more than once a week). We hypothesize that the coefficient for this variable would be positive, indicating that support for the religious exemption occurs with greater likelihood among those with high religiosity.

Moral conservatism

Respondents were asked three questions about the degree to which they find abortion, contraception, and divorce to be “morally acceptable.” We coded each variable as a simple binary variable: 1 if the respondent found the action morally wrong and 0 otherwise. We then created an additive scale that ranges from 0 to 3, and we hypothesize that finding a combination of abortion, contraception, and divorce morally wrong would be positively related to individuals’ support for an exemption to the contraception mandate.

Political Attitudes

Partisan identification

An individual’s partisan identification is strongly related to a wide range of political attitudes and behaviors, and we contend that partisanship would be strongly related to Americans’ views on the HHS contraception mandate. We measure partisan identification as a five-point scale, ranging from -2 (strong Democrat) to +2 (strong Republican). We suggest that Republicans would be more likely to support the religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate; therefore, we hypothesize that the coefficient for this variable would be positive.

Political ideology

The HHS contraception mandate is likely to separate liberals and conservatives, who differ in their views about the role of government. We suggest that conservatives would be more likely than liberals to support an exemption to the HHS mandate. This variable is measured on a five-point scale, ranging from 0 (strong liberal) to 4 (strong conservative). We hypothesize that this variable would be positively related to support for the exemption to the contraception mandate.

Tea Party support

Those who identify with the Tea Party should be particularly strong in their opposition to the HHS contraception mandate. Tea Party adherents are strongly opposed to what they consider to be overreach by the federal government and, for many such adherents, the actions of the Obama administration were evaluated in negative terms. We code Tea Party support +1 for those who agree with the Tea Party movement, 0 for those who have no opinion, and -1 for those who are opposed. This variable should be positively related to support for the exemption to the HHS contraception mandate.

Presidential approval

Pew Research Center survey respondents were asked if they approve or disapprove of the way Barack Obama is handling his job as president. This variable is coded on a four-point scale, ranging from 0 (very unfavorable) to 3 (very favorable). The HHS contraception mandate is tied closely to the Obama administration, so we expect those with favorable views toward President Obama to have less favorable views toward an exemption to the HHS mandate. Hence, we hypothesize that the coefficient for this variable would be negative.

Support for government regulation

Americans vary in their tolerance for the regulatory state in that some perceive that we have too much regulation and that regulation is negative, whereas others perceive that regulation is good and that more is needed. We also speculate that general support for regulation would be inversely related to support for an HHS contraception mandate exemption. This variable is coded 2 for individuals who perceive that “government regulation of business is necessary to protect the public interest”; 1 for individuals who respond “neither” or “don’t know”; and 0 for those who agree that “government regulation of business usually does more harm than good.” We suggest that individuals who have more favorable views toward government regulation would be more supportive of the HHS contraception mandate and subsequently less supportive of a religious exemption. Therefore, we hypothesize that the coefficient for this variable should be negative.

Demographic and Socioeconomic Attributes

We also consider the effects of various demographic and socioeconomic attributes on support for a religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate. Some of these variables (e.g., gender, number of children in household, and race) can be viewed as having a substantive effect on support for an exemption to the HHS mandate; however, we also include several variables as standard statistical controls.

Gender

Perhaps the most important of our demographic variables is gender. The clash of values to which we allude involves a competition between different value systems. Some of this clash of values is encapsulated in the religion and political variables described previously, and significant gender differences on some of these variables may partly explain any observed gender effects.Footnote 2 However, in addition, there may be a self-interest component that surpasses specific individual values. The HHS contraception mandate is perceived as a program to benefit women, many of whom did not have contraceptive coverage in their insurance plans before adoption of the mandate. Of course, women become pregnant whereas men do not, and women use prescription contraception whereas men do not. Many forms of contraception are not particularly expensive; however, the cost is not trivial and, without contraception coverage in insurance plans, these costs can add up, particularly for women. Therefore, we hypothesize that women should be more supportive of the contraception mandate and less supportive of an exemption to this policy. We code gender 1 for women and 0 for men, and we hypothesize that the effect of gender on the HHS mandate exemption is negative.

Children in household

In addition to the possible effects of self-interest tied to gender, it is possible that—controlling for the effects of other variables—families with more children would be more supportive of the HHS contraception mandate for family-planning purposes. To consider these effects, we include a variable that represents the number of children in respondents’ households under the age of 18. We hypothesize that the coefficient for this variable would be negative, indicating that increases in the number of children depresses support for an exemption to the HHS contraception mandate.

Race/Ethnicity

President Obama drew particularly strong support from Americans in minority communities, so we expect that policies proposed by a president who was popular in the African American, Latino, and Asian American communities to receive stronger support relating to the ACA, his signature legislative achievement. We measure race and ethnicity through a series of binary variables for blacks, Hispanics, Asians, mixed race, other race, and whites; each variable is coded 1 if the respondent is in the relevant racial/ethnic group and 0 otherwise. Because the dichotomous variable for whites is the excluded (i.e., contrast) variable, we hypothesize that the coefficients for all of the other racial/ethnic variables would be negative.

Other control variables

We also control for the effects of education, family income, and age. First, respondents were asked to identify the highest level of school completed or the highest degree earned. Education is coded as an eight-point scale, ranging from 0 (less than high school) to 7 (postgraduate or professional degree). We hypothesize that those with higher levels of education would be less supportive of an exemption to the contraception mandate; hence, the coefficient for this variable should be negative. Second, we measure family income as a nine-point scale, ranging from 0 (under $10,000 per year) to 8 ($150,000 per year and more). The expected effect of family income is indeterminate; therefore, we include this variable simply as a control to capture possible income effects. Finally, we include age in our model; this variable is measured as a respondent’s age in years. We expect that older Americans would be less supportive of the HHS contraception mandate and therefore more supportive of the religious exemption; hence, the coefficient for this variable should be positive.

Descriptive statistics for all of the variables in our analysis are in appendix table A2.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

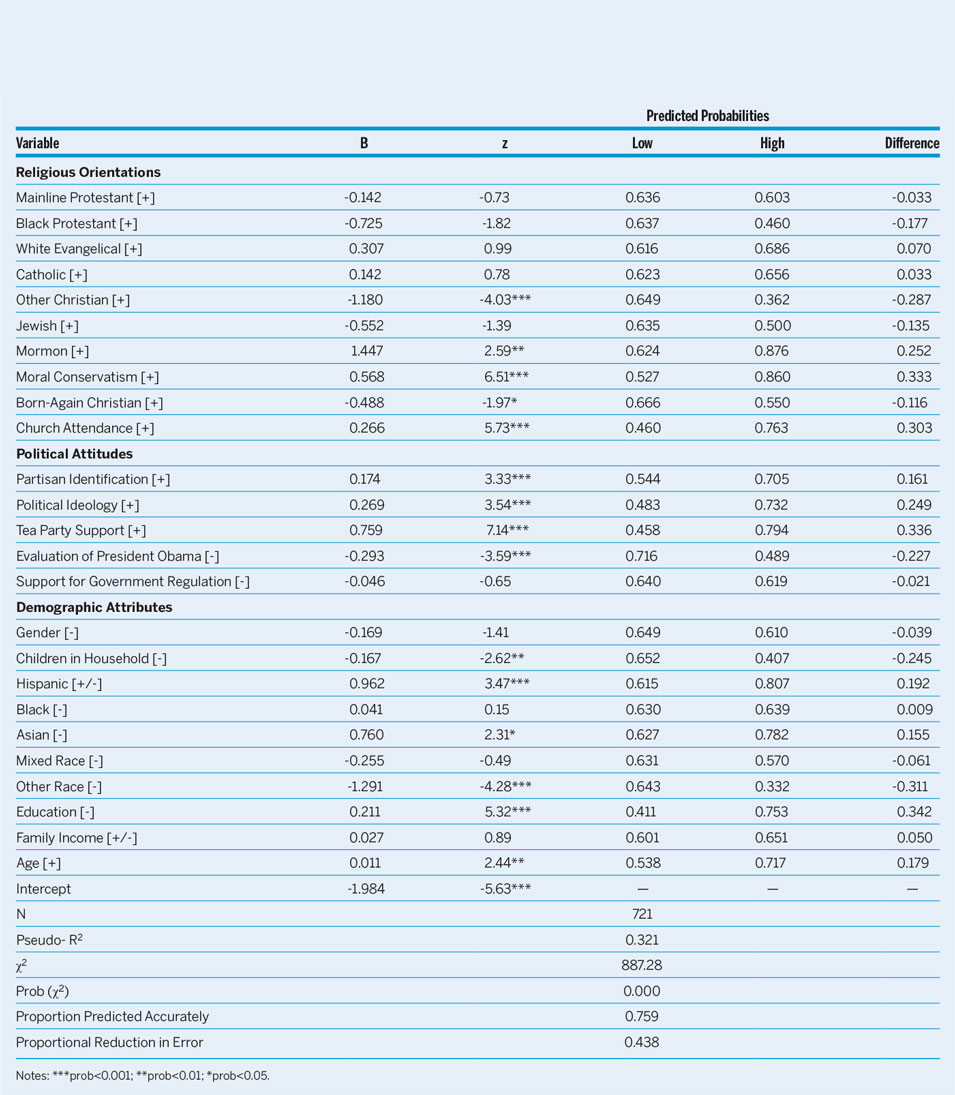

Table 1 lists results for our logit model of support for a religious exemption from the HHS contraception mandate. Logit coefficients are not intuitively interpreted because they represent changes in the log-odds ratio associated with a one-unit change in the independent variable. Hence, in addition to the coefficients and tests of statistical significance, we also report predicted probabilities that respondents support the HHS mandate exemption associated with the highest and lowest values on each independent variable, holding the values of all other variables constant at their means. The difference in these predicted probabilities provides an approximate measure of the relative importance of each independent variable—that is, the maximum effect of each independent variable across the full range of values—in shaping support for a religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate.

Table 1 Logit Estimates for Model of Individuals’ Support for a Religious Exemption to the HHS Contraception Mandate

Notes: ***prob<0.001; **prob<0.01; *prob<0.05.

We begin by pointing out that our model fits the data reasonably well. The likelihood ratio χ2 is highly significant, indicating that the model is a significant improvement over the null intercept-only model. Moreover, the pseudo-RFootnote 2 value of 0.32 is respectable, and the model accurately predicts support for (or opposition to) the HHS mandate exemption in 75.9% of the observations. This represents a proportional reduction in error over the null model of 0.438, meaning that 44% of the observations predicted inaccurately by the null model are now predicted accurately by our substantive model.Footnote 3

Religious Orientations

We find that the effects of the religion variables are mixed, with some of them having a powerful influence on the dependent variables and others having only a weak or null effect. First, the religious-tradition variables have surprisingly negligible effects. Recall that the excluded contrast group is secular respondents (i.e., atheists, agnostics, and other secular individuals), so we expect that identification with each religious group would be positively related to support for the religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate. However, this is clearly not the case. Mormons are significantly more likely to support this exemption (b = 1.447, z = 2.59), and this translates into a 0.252 higher probability of support for the exemption than similarly situated secular respondents. However, no other group has a significantly higher probability of supporting the HHS mandate exemption than secularists, controlling for the effects of other independent variables. Catholics (b = 0.142, z = 0.78) are no different than secularists in their support for the exemption, as are Jews (b = -0.552, z = -1.39), mainline Protestants (b = -0.142, z = -0.73), black Protestants (b = -0.725, z = -1.82), and even white evangelical Protestants (b = 0.307, z = 0.99).Footnote 4 Only “other” Christians (b = -1.180, z = -4.03) are significantly less supportive of the HHS contraception mandate exemption.

Those who attend religious services every week had a probability of supporting the exemption that was 0.303 higher than those who never attend religious services (i.e., 0.763 to 0.460). It appears that strong adherents to their religious faith were significantly more likely to support a religious exemption to the HHS mandate than those who are not strong religious adherents.

Second, two religion variables have powerful effects on support for the exemption from the HHS contraception mandate. One problem with religious self-identification is that there is variation in the degree to which individuals claiming the same religion adhere to doctrinal teaching, are active in their religious life, and prioritize the practice of religious faith in their daily lives. Individuals for whom their religious faith is important and who attend religious services on a regular basis should be more likely to develop attitudes and behaviors that are compatible with those religious teachings. Given this, it is not surprising that we find that church attendance is among the strongest predictors of support for the HHS contraception mandate exemption (b = 0.266, z = 5.73). Those who attend religious services every week have a probability of supporting the exemption that is 0.303 higher than those who never attend religious services (i.e., 0.763 to 0.460). It appears that strong adherents to their religious faith are significantly more likely to support a religious exemption to the HHS mandate than those who are not strong religious adherents.Footnote 5

We also find a strong effect of moral conservatism on support for exemption to the HHS contraception mandate (b = 0.568, z = 6.51). Individuals who exhibit a high level of moral conservatism—that is, who find abortion, contraception, and divorce morally objectionable—have a probability of supporting the HHS mandate exemption that is 0.333 higher than those who exhibit low moral conservatism (i.e., 0.860 to 0.527), controlling for the effects of other independent variables. Simply stated, moral conservatives are significantly more supportive of the HHS contraception mandate exemption than moral liberals.

Political Orientations

Table 1 shows that political attitudes have strong effects on support for an exemption to the HHS contraception mandate. Simply stated, how Americans think about partisanship, ideology, the Tea Party, and President Obama all have powerful effects on the dependent variable. Preference for a religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate is strongly influenced by partisan identification (b = 0. 174, z = 3.33) and political ideology (b = 0.269, z = 3.54). Holding the other independent variables constant, the probability that strong Republicans support the exemption is 0.161 higher than that for similarly situated strong Democrats (i.e., 0.705 to 0.544), and the probability that strong conservatives support the exemption is 0.249 higher than for strong liberals (i.e., 0.732 to 0.483). The effect of Tea Party support is among the strongest in the model (b = 0.759, z = 7.14); 0.794 of those who support the Tea Party also support the exemption from the HHS contraception mandate, compared to only 0.458 of those who do not support the Tea Party, for a difference of 0.336. As expected, we also find that favorable attitudes toward President Obama depress support for the exemption (b = -0.293, z = -3.59), with strong Obama supporters exhibiting a predicted probability that is 0.227 lower than strong Obama opponents. Finally, we find little evidence that support for government regulation matters for support for the exemption (b = -0.046, z = -0.65).Footnote 6 Overall, our results make it clear that these political-attitude variables activate the clash of values over this issue and therefore are major drivers of how Americans think about the religious exemption from the HHS contraception mandate.

Gender

Because women are the primary beneficiaries of contraceptive services, we hypothesize that they should be more supportive of the HHS contraception mandate in general and therefore less supportive of a religious exemption to the mandate. At the simplest (bivariate) level, we find support for this hypothesis. Among men, 62.5% support the religious exemption to the contraception mandate; however, among women, this percentage decreases to 49.6%. This bivariate difference is statistically significant (z = -4.04). Surprisingly, after controlling for the effects of other variables, we find that gender is unrelated to the dependent variable (b = -0.169, z = -1.41); simply stated, women are no more and no less likely to oppose the exemption to the HHS contraception mandate. Clearly, the effect of gender declines to statistical nonsignificance when controls for other independent variables are introduced.Footnote 7

Demographic/Socioeconomic (Control) Variables

Regarding demographic and socioeconomic control variables, we find mixed effects but also several variables that have the expected effect on support for the HHS contraception mandate exemption. First, the number of children in respondents’ households is inversely related to a preference for the HHS mandate exemption (b = -0.167, z = -2.62): those with no children are predicted to support the exemption with a probability of 0.652, whereas those with six or more children have a predicted probability of 0.407—a difference of -0.245.Footnote 8

Second, there also are some effects of race and ethnicity, although these variables do not always behave as expected. All of the coefficients for these variables represent differences with whites, which is the excluded (i.e., contrast) category. Surprisingly, black (b = 0.041, z = 0.15) and mixed-race respondents (b = -0.255, z = -0.49) are neither more nor less supportive than whites of the HHS contraception mandate, whereas other-race respondents (b = -1.291, z = -4.28) are significantly less likely than whites to support an exemption to the mandate. Conversely, Hispanics (b = 0.962, z = 3.47) and Asian Americans (b = 0.760, z = 2.31) are more likely than whites to support the exemption to the HHS mandate by margins of 0.192 and 0.155, respectively.

Third, education has a surprisingly strong positive effect on individuals’ propensities to support the HHS contraception mandate exemption (b = 0.211, z = 5.32). The most highly educated (i.e., those with a postgraduate degree) are predicted to have a probability of supporting the exemption that exceeds the probability for the lowest education level (i.e., those who completed eighth grade or less) by 0.342 (i.e., 0.753 to 0.411).

Fourth, family income does not have an effect on the dependent variable but age does (b = 0.011, z = 2.44): older Americans are more supportive of a religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate than their younger counterparts.

Auxiliary Analyses

Appendix 2 contains additional analyses for interested readers. Specifically, we consider whether religiosity and gender—two core variables that reflect the clash of values to which we refer throughout this article—shape how Americans translate their political attitudes, religious beliefs and attachments, and demographic attributes into support for or opposition to the religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate. Furthermore, in appendix 3 we present figures that illustrate the effects of key variables—church attendance, gender, partisan identification, political ideology, and support for President Obama—on support for the religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate.

DISCUSSION

The considerable disagreement over the HHS contraception mandate reflects a clash of rights. On one hand are those who argue—forcefully and convincingly—that individuals have a right to receive contraception services in the insurance programs provided by their employers and further that the federal government can compel employers to provide such coverage. For these individuals, religious beliefs do not absolve employers of the obligation to support the health-care choices of their employees, many of whom may not share the employers’ religious beliefs. On the other hand are those who argue—forcefully and convincingly—that religious beliefs (and the right to practice those beliefs) are protected both by the US Constitution and by statute, and further that these protections encompass the rights of employers with sincerely held religious beliefs to not be forced to violate those beliefs as a precondition of entering the public sphere. For those who prioritize religious freedom, employers have the right to an exemption from federal law and to deny employees contraception coverage if providing it contradicts their sincerely held religious beliefs.

How do Americans resolve the dispute between completing rights claims as it pertains to the HHS contraception mandate? We suggest that the differences between these two sides on this issue are quite stark. First and foremost, we find that religion variables, unsurprisingly, are major determinants of attitudes toward the religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate. Whereas religious-denomination variables have only inconsistent effects, we find that church attendance and moral conservatism on abortion, contraception, and divorce are both positively and strongly related to support for the religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate. It appears that those who are highly religious and who hold traditional views on moral issues think about the clash of rights differently than other Americans. Second, we find that those who support the religious exemption from the HHS contraception mandate and those who do not are strongly differentiated by various political attitudes: partisan identification, political ideology, support for the Tea Party, and evaluations of President Obama. These are core political variables that differentiate Americans on a wide range of policy issues, and the religious exemption from the HHS contraception mandate is no exception. Indeed, these political variables are likely to differentiate individuals on this issue for the foreseeable future.

Third, we also consider how demographic attributes differentiate supporters and opponents of a religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate. It appears that women are not, as expected, significantly less likely than men to support the religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate. Gender, however, does moderate the effects of other independent variables on support for the religious exemption (see appendix tables A7 and A8). Moreover, we find that the number of children in households is negatively related to support for the religious exemption; individuals in relatively large families are more likely to support the HHS contraception mandate.

Fourth, we find that education and age are positively related to support for the religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate. The finding for education is somewhat surprising but suggests that individuals with higher levels of education are more likely to support a religious exemption.

Where do we go from here? First, we suggest that the HHS contraception mandate is the type of issue that creates strong disagreements between groups of individuals who have vastly different conceptions of individual rights and the priorities among competing rights claims.

Where do we go from here? First, we suggest that the HHS contraception mandate is the type of issue that creates strong disagreements between groups of individuals who have vastly different conceptions of individual rights and the priorities among competing rights claims. Many issues confronting democratic polities involve such disagreement over competing visions about the relative merits of individual rights. It is important for scholars studying attitudes toward “clash-of-rights” issues to explicitly account for these competing views about which rights take priority over others. This may require the creation of new survey questions that explicitly cast different views of rights against one another. Second, many of the issues that involve competing rights end up being settled in the US judicial system, often by the US Supreme Court. What is the effect of court decisions on individuals’ perceptions of which rights take priority over others? Does a court decision that favors one set of rights over another result in a change in individuals’ attitudes about which rights should be prioritized, or do these attitudes hold steady once the legal status of different rights regimes is clarified by judicial decisions? Do court decisions that favor one set of rights over another result in diminished support for the American political system, especially in terms of the sense of legitimacy toward the courts?

Third, we contend that clash-of-rights issues such as the religious exemption to the HHS contraception mandate will continue to divide Americans and therefore are worthy of further study. As noted previously, the future of the contraception mandate and the religious exemption is uncertain, particularly given the election of a president who has expressed strong opposition to the Obama administration’s position on these issues. The Trump administration and HHS have already taken steps to adopt a strong religious exemption to the contraception mandate, though the outcome of court challenges by some states remains to be seen. Moreover, given the appointment of Neil Gorsuch to the US Supreme Court, the Court may be more receptive to a religious exemption. We suggest, however, that numerous issues involve the clash of rights and continue to divide the American mass public. How do Americans differentiate themselves on other issues (e.g., the rights of LGBT Americans to live without discrimination versus the rights of individuals to freely exercise their religious beliefs) that pit one conception of rights against another? We suggest that it is important to extend this research program to other clash-of-rights issues that (will continue to) divide Americans so strongly.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517002517

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to three anonymous reviewers and the editors of this journal for their thoughtful and constructive comments on previous versions of this article. We remain responsible for any remaining errors.