INTRODUCTION

Central to the success of the Chinese economy in the last three decades is the rise of private entrepreneurship with its potential to set the economy on a high growth path (Krug & Mehta, Reference Krug, Mehta and Krug2004). According to a nationwide survey, domestic private firms account for 60% of industrial output, 50% of total tax revenue, and 75% of total employment in 2015 (China Daily online). Most importantly, this phenomenal growth was achieved even though private firms face various forms of institutional discrimination. However, many aspects of the behavior of domestic private firms remain unclear. HR development investment is one area of scholarly debate.

One stream of research views Chinese private firms as sweatshops with exploitative employment practices due to their scarce financial resources (Cooke, Reference Cooke2005; Eckholm, Reference Eckholm2001). Compared with state-owned or foreign-owned firms, HR systems in private firms tend to be more pragmatic and short-term oriented. Training and development programs are largely viewed as costly and disruptive to production, and consequently, there is little long-term strategic planning for HR development (Shen, Reference Shen2010; Wei & Lau, Reference Wei and Lau2008; Zhu & Warner, Reference Zhu and Warner2005). However, researchers also find that some private firms follow a people-oriented approach and actually make HR-related investment. For example, based on a nation-wide sample of 1,350 employees in 161 private firms, Lin (Reference Lin, Tsui, Bian and Chang2006) found that 34.78 percent of the surveyed firms adopted a broad range of investments to cultivate the capability and loyalty of their employees. Gong, Law, and Xin (Reference Gong, Law, Xin, Tsui, Bian and Chang2006) showed that there were no significant differences in HR investment between private firms and other types of firms in a sample of 117 firms. Such inconsistent evidence leads to two questions: Why are some private firms likely to make HR development investments given their cost pressures? What factors drive such investment in Chinese private firms?

Strategic human resource management (SHRM) scholars suggest that the long-term competitive advantages of firms reside in skilled and knowledgeable employees who are motivated to contribute their discretionary efforts towards organizational goals (Jiang, Lepak, Hu, & Baer, Reference Jiang, Lepak, Hu and Baer2012; Lengnick-Hall, Lengnick-Hall, Andrade, & Drake, Reference Lengnick-Hall, Lengnick-Hall, Andrade and Drake2009). Based on this dominant view, researchers suggest that HR development investment is a strategic choice for firms, and managerial myopia is a major barrier for such investment in many firms (Kaufman & Miller, Reference Kaufman and Miller2011). This idea has received support from a series of studies exploring why firms adopt high-investment HR practices (Ordiz-Fuertes & Fernández-Sánchez, Reference Ordiz-Fuertes and Fernandez-Sanchez2003; Pil & MacDuffie, Reference Pil and MacDuffie1996; Som, Reference Som2007; Thompson & Heron, Reference Thompson and Heron2005; Wei & Lau, Reference Wei and Lau2005). Despite this progress, current research has not examined what characteristics of key decision makers influence HR development investment. This knowledge is important because according to the strategic choice perspective (Child, Reference Child1972; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik1978), the outcome of organizations is a product of key actors’ decisions and the characteristics of these actors would help us understand why they make certain choices. Drawing on this perspective, we propose two variables, private entrepreneurs’ education and governance team completeness, to advance our knowledge about HR development investment in private firms.

However, the strategic choice perspective may not provide a complete understanding of HR development investment because private firms face the added burden of ‘liability of privateness’ in transitional China (Chen, Reference Chen2007; Ma, Lin, & Liang, Reference Ma, Lin and Liang2012). Not only must they compete and win in the market, they must also maintain a certain level of legitimacy so as to be politically viable. Accordingly, the institutional perspective, which views firms as entities seeking approval and legitimacy in a socially constructed environment (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Meyer & Rowan, Reference Meyer and Rowan1977; Peng, Wang, & Jiang, Reference Peng, Wang and Jiang2008), is expected to provide additional insights into HR development investment in private firms beyond the strategic choice perspective. Building on a review of Chinese institutional environment for private firms, we propose political affiliation (whether private entrepreneurs are members in the People's Congress or the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference) and former state ownership (whether the private firm was restructured from a state-owned firm) to complement the two strategic-choice based variables we include. Furthermore, we expect that perceived government support for private business encourages those entrepreneurs who see the strategic value of HR to actively make more HR development investment. This combination of the strategic choice and institutional perspectives allows us to make a contextualized analysis of HR development investment in Chinese private firms. Warner (Reference Warner2009) highlighted that many variations and paradoxes exist in Chinese HR practices because it is ‘Western, yet Eastern’, ‘Capitalist, yet Socialist’. A contextualized approach, which advances the importance of contextual factors in understanding HR practices and effectiveness, is particularly necessary in advancing our knowledge of Chinese HR practices, including HR development investment in private firms (Kim & Wright, Reference Kim and Wright2011; Zhang, Nyland, & Zhu, Reference Zhang, Nyland and Zhu2010).

In this study, we intend to make three contributions to the HR literature. First, we not only extend HR research by further identifying specific characteristics of key decision makers that explain HR development investment, but incorporate the neo-institutional perspective and demonstrate that HR development investment is also a response to legitimacy pressures in China. In the HR literature, institutional theory has been embraced largely to compare HRM practices across countries or to demonstrate that multinational companies differ systematically in their overseas operations (Björkman, Fey, & Park, Reference Björkman, Fey and Park2007; Chowdhury & Mahmood, Reference Chowdhury and Mahmood2012; Gooderham, Nordhaug, & Ringdal, Reference Gooderham, Nordhaug and Ringdal1999; Lawler, Chen, Wu, Bae, & Bai, Reference Lawler, Chen, Wu, Bae and Bai2011; Rosenzweig & Nohria, Reference Rosenzweig and Nohria1994). However, mainstream SHRM research has been criticized for its decontextualized approach, characterized by ‘little or no attention paid either to the institutional environment or to the political and economic relationship in which firms are embedded’ (Delbridge, Hauptmier, & Sen Gupta, Reference Delbridge, Hauptmier and Sen Gupta2011: 487). Therefore, applying institutional theory to construct a contextualized analysis of HR development investment can yield valuable insights (Boon, Paauwe, Boselie, & Den Hartog, Reference Boon, Paauwe, Boselie and Den Hartog2009; Kim & Wright, Reference Kim and Wright2011; Paauwe & Boselie, Reference Paauwe and Boselie2005).

Second, this study extends the contingency perspective in SHRM literature (Lengnick-Hall et al., Reference Lengnick-Hall, Lengnick-Hall, Andrade and Drake2009) by revealing institutional influences as an important contingency factor for HR development investment. Different from commonly examined contingency factors (i.e., industry and organizational strategy), we demonstrate how institutional arrangement for private business (i.e., perceived government support) modifies the extent to which strategic choice variables influence HR development investment. This knowledge advances our understanding of the interaction between individual decision makers and their institutional environment in an emerging economy (Child, Reference Child1997; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Wang and Jiang2008).

Last, this study offers policy implications for emerging economies. In order to enhance their competiveness in the global market, firms from emerging economies have increasingly invested in HR (Brown, Lauder, & Ashton, Reference Brown, Lauder and Ashton2008). This investment, however, is impaired if private entrepreneurs perceive that their governments are not improving protection for private business. Therefore, our China-based contextualized analysis not only extends and enriches current HR research, but also provides policy implications for emerging economies undergoing an economic transition.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

Domestic Private Firms in China

The private sector was not legally permitted until 1978 in P. R. China. When the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took power in 1949, Communist ideology became the official and dominant ideology in China. This Marxist-based ideology states that the private ownership of economic assets is the source of class exploitation, and the CCP should represent and protect the interests of working people (Tsang, Reference Tsang1996). Guided by such an ideology, private firms were made illegal and all private business was nationalized. The economic reforms beginning in 1978 brought entrepreneurial opportunity and a rebirth of private firms. However, the government sought to contain private business as a peripheral, subordinate sector in the Chinese economy (Hong, Reference Hong2004; Ma & Parish, Reference Ma and Parish2006; Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012). New private businesses face both ‘the liability of newness’ and ‘the liability of privateness’ in their business operations (Krug & Mehta, Reference Krug, Mehta and Krug2004; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Lin and Liang2012). Consequently, private firms are mainly concentrated in certain competitive industries, such as the textile, electronics, and building materials industry. Their presence is significantly lower in finance, power, coal, petrochemicals, tobacco, and other monopoly industries (Chen, Luo, & Li, Reference Chen, Luo and Li2014).

HR Development Investment as a Strategic Choice to Market Competition

As we mentioned, domestic private firms face the liability of newness in the market. In the early years of development, they commonly started in low skill, low cost manufacturing industries, and relied on cheap labor, long working hours, and low benefits to maintain their growth. With the gradual shift from a producer-centered to a consumer-centered society in China, the exploitative treatment of workers is no longer a viable long-term strategy for business success. Private firms increasingly face the challenge of attracting and retaining skilled employees (Cooke, Reference Cooke2005). In a meta-analysis, Combs, Liu, Hall, and Ketchen (Reference Combs, Liu, Hall and Ketchen2006) found that on average, a one-standard-deviation increase in investment in HR systems including training and development led to an average 4.6 percentage-point increase in gross return on assets (ranging from 5.1% to 9.7%). Therefore, in order to maintain sustainable growth during a market transition, HR development investment can be a viable strategic choice for private firms.

Built on the above understanding, we embrace the strategic choice perspective (Child, Reference Child1972; Reference Child1997) to analyze why domestic private firms make HR development investment. This perspective argues that purposeful actions by organizational decision makers shape the actions and fates of their firms. According to this perspective, explanation of HR-related decision should begin with an analysis of whether the management team has the foresight and desire to invest in the development of the firm's staff. However, this is not a straightforward choice for domestic private firms, because private entrepreneurs may not see the strategic value of HR development investment, or have the incentive to make such investment, particularly in private firms with scarce resources. For some, there is a high level of uncertainty in such investment because of the lack of ownership rights over employees, unlike financial capital assets (Harrell-Cook & Ferris, Reference Harrell-Cook and Ferris1997). There is no guarantee that firms will even see a recovery of the amount invested, let alone a return on long-term oriented HR investment. Therefore, before making investments in HR development, private entrepreneurs must understand and believe in the strategic value of their people and avoid a shortsighted view of HR. Because private entrepreneur's education and governance team completeness can develop a belief in and understanding of the strategic value of people in sustaining competitive advantage, we propose that the two variables should be positively related to HR development investment in private firms.

Private entrepreneurs’ education

Education serves as a measure of an individual's stock of knowledge, which enhances the private entrepreneur's capability to analyze the competition, obtain useful insights for business operations, and design and implement competitive strategies and actions (Obstfeld, Reference Obstfeld2005). We expect that decision makers with better education are more likely to view HR as a source of competitive advantage and build their strategic planning and actions on the HR of the firm. First, generally speaking, a more educated entrepreneur is more likely to be successful, especially when industry is more knowledge based, and therefore have a stronger motivation to make investment to develop their people. Van der Sluis, van Praag, and Vijverberg (Reference Van der Sluis, Van Praag and Vijverberg2005) performed a meta-analytic review of 203 studies from emerging economies about the relationship between education and entrepreneurial performance. They found that education, irrespective of how it is measured, positively affects entrepreneurial performance. Unger, Rauch, Frese, and Rosenbusch (Reference Unger, Rauch, Frese and Rosenbusch2011) reached the same conclusion in a recent meta-analytic review of 70 independent samples. Thus, private entrepreneurs with higher education are more likely to realize the importance and true value of education and knowledge for their business success. As long as they see the strategic value of knowledgeable and skillful employees in market competition, they would have the motivation to make HR-related investment and develop their people. Therefore, we expect that the educational attainment of key decision makers is a foundation of the strategic choice of HR development investment in the competition.

Second, specific to the Chinese context, we expect that private entrepreneur's education is important for viewing HR development investment as a strategic choice in the economic transition. With the deepening of economic reforms and the rapid development, there is a gradual transition from simple, low cost manufacturing to higher quality and more sophisticated products as well as more complex manufacturing technologies, particularly in the economically developed areas. This change has created the demand for private entrepreneurs to rapidly adapt. In particular, they need more and better-educated (i.e., more skilled) employees to maintain continuous growth (Cooke, Reference Cooke2005). However, HR development investment may not be an easy decision for private entrepreneurs. During the market transition, the high level of uncertainty derived from the rapid technological progress and government policies/regulations are likely to force private entrepreneurs to focus on the short-term needs of their companies (Krug & Mehta, Reference Krug, Mehta and Krug2004; Luo, Reference Luo2006). Due to the enormous cost pressure in competitive industries, employee training and development is likely to be viewed as costly and disruptive to production (Shen, Reference Shen2010). Therefore, without a deep understanding of and stronger belief in the importance and value of HR development, private entrepreneurs can easily be dragged into the short-term mentality and become less likely to invest in HR development for the long-term competitive advantage.

Based on the above discussion, we expect that Chinese private entrepreneurs with higher educational attainment are more likely to understand and believe in the strategic value of HR and have a stronger motivation to make HR development investment. Equipped with business knowledge and analytic tools, more educated private entrepreneurs are likely to have better business acumen and understanding of market competition, can see beyond the immediate market situation, and pay much attention to the long-term competitiveness of their firms. They are more likely to avoid the managerial myopia and realize that HR development investment, rather than exploitative employment practices, is a strategic choice for their firms to gain competitive advantage and maintain sustainable growth during the market transition. We thus hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1a. Private entrepreneurs’ education level will be positively related to HR development investment in Chinese private firms.

Governance team completeness

Different from education, governance team completeness represents the characteristics of the management team in a private firm: whether there is a complete governance team within the firm, including the board, managing director, and audit committee. As we argued, intensive market competition and rapid technological progress necessitates faster and higher quality decision-making in private firms. However, due to their newness, many private entrepreneurs did not have adequate expertise to develop sound business practices and the limited managerial talent within a family cannot meet such challenges (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Lin and Liang2012; Zhang & Ma, Reference Zhang and Ma2009). In order to match the complexity of their competitive environment, private entrepreneurs with the foresight may proactively surround themselves with professional managers from outside the family but with outstanding education and managerial experience (Krug & Mehta, Reference Krug, Mehta and Krug2004; Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012). These professional managers advise private entrepreneurs on strategic and operational issues. With a governance team in place, private entrepreneurs are exposed to and learn the view of building and sustaining competitive advantage through HR, and are prompted to think deeply and thoroughly about the long-term strategic planning of their firms. We should note that in the Chinese context, forming a governance team is quite difficult in private firms, because founding entrepreneurs usually have a strong emotional attachment to their firms, prefer to exercise personal control, and usually act as the ultimate decision maker (Redding, Reference Redding1990; Zhang & Ma, Reference Zhang and Ma2009). Therefore, whether a private firm has a complete governance team is an important indicator of the openness of private entrepreneurs to professionals, and their input in the decision-making process. We expect that a complete government team provides a channel for private entrepreneurs to access professional advice and knowledge, reduces their tendency to engage in short-term oriented employment practices, and guides them to invest more in HR development.

While we propose that a governance team will provide the needed professional and specialized knowledge and advice for a sound strategic decision, we do not expect these managers to exert great pressure or constraint on private entrepreneurs. This is mainly because most private entrepreneurs maintain strong control over their firms in China. Their exemplary competency and legendary accomplishment provide legitimacy for their centralized decision-making within their firms. Meanwhile, both the institutional and cultural factors in China put those professional managers outside the innermost power circle of private entrepreneurs (Zhang & Ma, Reference Zhang and Ma2009). It is thus very difficult for those professional managers to move from professional advisors to true decision-makers who can constrain or pressure the entrepreneurs who run the firms. Therefore, a complete governance team is largely a source of constructive professional advice, but is unlikely to constrain the decisions of private entrepreneurs. We therefore hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1b. Governance team completeness will be positively related to HR development investment in Chinese private firms.

HR Development Investment as a Response to Institutional Environment

The strategic choice-based explanation suggests that private entrepreneurs make HR development investments to handle market challenges and gain long-term competitive advantage. However, this proactive approach only tells one side of the story. In China, the transition to a market economy has yet to be completed and private firms face the additional burden of ‘liability of privateness’ in China. Therefore, we need to examine not only the strategic rationale behind HR development investment, but also the institutional environment in which private firms are embedded. Different from the proactive role of private entrepreneurs highlighted in the strategic choice perspective, institutional theorists stress the importance of institutionalized expectations imposed upon them by their environment (DiMaggio & Power, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Scott, Reference Scott2008). From this perspective, the need for legitimacy exerts environmental pressures on private entrepreneurs, which makes HR development investment often a reactive response to their institutional environment.

According to DiMaggio and Powell (Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983), three institutional pressures influence decision-making in organizations: coercive pressure, which stems from political influence and the need of sociopolitical legitimacy; mimetic pressure, which results from firm responses to their environments; and normative pressure, which is associated with professionalization. As we discussed, there is a fundamental difference between private entrepreneurs’ goal of maximizing their own profits and the Communist ideology that advances an egalitarian society by building up the public sector of the economy. As a result of market-oriented economic reforms, the pursuit of private property has gradually become a direct threat to the dominant Communist ideology (Wang, Reference Wang2013). The increasing income disparity within China has also raised the question of the ‘problematic wealth’ or ‘original sin’ (‘yuan zui’) of private businessmen, the improper or illegal accumulation of wealth via collusion with the holders of power or exploitation of others (Hong, Reference Hong2004). These issues have sent the CCP a strong signal on social stability and led to a call for private entrepreneurs to take social responsibility and help create a harmonious society (Wang, Reference Wang2013). Facing skepticism from both the government and the public, private entrepreneurs have a strong incentive to distance themselves from the negative stereotypes of ‘profiteer’ or ‘speculator’, and build a positive image through their contributions to society (Ma & Parish, Reference Ma and Parish2006; Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012). Within this context, we consider coercive pressure from political influence as the key institutional influence for understanding HR development investment in private firms, because a powerful institutional agent, the government, establishes legitimacy guidelines for private firms and defines appropriate actions for them in contemporary China (Deephouse & Suchman, Reference Deephouse, Suchman, Oliver, Suddaby and Sahlin-Andersson2008). Accordingly, we propose two channels for transmitting institutional influence on HR development investment: private entrepreneurs’ political affiliation and private firms’ former state ownership.

Political affiliation

As we discussed, despite formal legislation granting the legal status of private business, the overall political environment remains antagonistic and private entrepreneurs have to deal with social hostility and prejudice from cadres and the public. Given the adverse political environment and institutional discrimination, private entrepreneurs have to respond to the institutional environment, albeit in a reactive way, in order to gain sociopolitical legitimacy needed for survival (Scott, Reference Scott2008). In the early 1990s, many private businesses chose to ‘wear a red hat’, that is, they registered themselves as ‘collective enterprises’ in order to be ideologically acceptable (Chen, Reference Chen2007; Naughton, Reference Naughton1994). Since the loosening of ideological and political constraints in the 1990s, some private entrepreneurs have sought a new and even more powerful ‘red hat’, i.e., membership in two political bodies, the People's Congress (PC) and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) (Li, Meng, & Zhang, Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006).

The PC and the CPPCC are the two major political councils in China. Each council meets once a year and serves as a forum for mediating policy differences between the Communist Party and various parts of Chinese society. The main functions of the PC are to make laws and policies and elect government officials, while CPPCC is an advisory body whose main function is to exercise democratic supervision of the Party and governments. Theoretically, memberships in the two political councils are instituted through elections. However, the Communist Party has great influence over the process of candidate nomination and all candidates must pass its screening process (Li et al, Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006). Therefore, the two institutions closely follow the Communist ideology and private entrepreneurs who have such affiliations are likely to fall under the direct and strong influence of the dominant ideology associated with these political organizations. They are expected to follow the Communist ideology more closely in their decisions than those who are not members of PC and/or CPPCC.

We make the above judgment for two major reasons. First, considering that the Communist Party controls the screening process, entrepreneurs who obtain these two political affiliations must have demonstrated their compliance with the Communist ideology to some extent. Otherwise, they are less likely to be selected and awarded such political status. Second, compared with their counterparts, private entrepreneurs with such political affiliations have greater opportunity to be exposed to and thus understand government initiatives and increase their sensitivity to the Communist ideology. As discussed above, there is a fundamental conflict between the Communist ideology and private property rights. Increased social tensions and uneasiness resulting from the economic reform have drawn the government's attention. In order to please the populace and showcase government care of the people, particularly the working class, the Chinese government actively has promoted certain ideologies in line with its Communist ideology, such as the pursuit of social equity and the creation of a harmonious society (Ma et al, Reference Ma, Lin and Liang2012; Wang, Reference Wang2013). Many of the initiatives involve investment in people, such as improving their potential and providing a better future for the people. Under the direct influence of such ideologies in various formal meetings and informal personal interactions, those private entrepreneurs involved in political institutions are keenly aware that the use of exploitative employment practices contradicts the ideologies advanced by the Communist Party, raises public concerns, and damages the image/reputation of the government (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012). Therefore, they are more likely to be under direct pressure from the Communist ideology to avoid exploitative practices and make investments in HR development.

In sum, we expect that private entrepreneurs who are members of the two political institutions of China are more likely to make HR development investment than their counterparts who do not belong to either of these political institutions. This action is largely driven by their compliance with the government's initiatives and their motivation to attain socio-political legitimacy in socialist China. This behavioral logic is different from the strategic motivation to gain a long-term competitive advantage through HR development investment in the market competition. We thus hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2a. After controlling for strategic choice-related variables, private entrepreneurs’ political affiliation will be positively related to HR development investment in Chinese private firms.

Former state ownership

Some domestic private firms were created through the restructuring of state-owned and collective-owned firms. In order to deepen the economic reform and deal with the large debts accumulated by the state-owned sector, the central government initiated a nationwide campaign to restructure its public sector and begin the privatization of state-owned firms (gai zhi) in 1995 (Garnaut, Song, Tenev, & Yao, Reference Garnaut, Song, Tenev and Yao2005). An important policy implemented by the central government is the policy of zhuada fangxiao (keep the large, let the small go). During this privatization process, a number of small and medium-sized state-owned and collective-owned firms were leased or sold to the private sector. In this study, we use former state ownership to capture the historical institutional imprint of private firms, which were restructured from state-owned or collective-owned firms (Marquis & Tilcsik, Reference Marquis and Tilcsik2013).

Before privatization, these firms were under the direct influence of Communist ideology and government administration. They traditionally adopted a paternalistic style of employment and invested relatively more in HR than domestic private firms, offering cradle-to-grave social welfare provisions and a training budget (Buck, Filatotchev, Demina, & Wright, Reference Buck, Filatotchev, Demina and Wright2003; Cooke, Reference Cooke2005; Zhu, Zhang, & Shen, Reference Zhu, Zhang and Shen2012). After ownership restructuring, a free market ideology was gradually instantiated in these firms to improve economic efficiency. However, since these firms inherited a sizeable number of the old workforce, they experienced pressure to maintain some of the preexisting rules and regulations because employees were used to the paternalistic care of the old state-owned system. Meanwhile, some private owners are also former managers of state-owned or collective-owned firms and are more likely to hang on to Communist ideologies and adhere to government initiatives. These historical factors place both moral and political constraints on their employment practices (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983). We expect that their HR practices are more difficult to change drastically even when the ownership changes, because HR policies tend to become institutionalized as a reflection of preexisting institutional forces (Marquis & Tilcsik, Reference Marquis and Tilcsik2013). We therefore expect that if private entrepreneurs operate a firm restructured from state-owned firms, they are more likely to be subject to the influences of Communist institutional practices, norms, and ideologies, and make greater HR development investment. Based on the foregoing, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2b. After controlling for strategic choice-related variables, former state ownership will be positively related to HR development investment in Chinese private firms.

Perceived Government Support for Private Business as a Moderator

Building on the above discussion, we further expect that government support for private business perceived by private entrepreneurs would serve as an important boundary condition for the effects of strategic choice variables on HR development investment. As North (Reference North1990) and Scott (Reference Scott2008) observe, economic institutional arrangements help to clarify the rules of the game and reduce uncertainty in economic activities. For example, in a mature market economy, business practices are largely shaped by contracts, private property rights, and the notion of liability and compensation as well as the consensus that innovation will be rewarded. All those institutional forces operate as filters through which rational actors perceive economic opportunities. However, the market transition in China has been, and continues to be, state initiated and experimental following a trial-and-error model (Chen, Reference Chen2007). During this transition, private entrepreneurs often face many ambiguities, and have to interpret unclear government policies and regulations.

We first expect that perceived government support for private business positively moderates the relationship between strategic-choice variables and HR investment in domestic private firms. Although private business faces many obstacles as a result of weak institutions, the market transition in China has been gradually moving forward. After granting legal status to private firms in 1988, the Chinese government strove to build a legal system by reestablishing judicial-legal organ and promulgating new legislation. A significant event related to private business is the implementation of the 2004 PRC Administration Law, which provides clear guidelines for government activities and protects the interests of Chinese citizens and legal persons. As a result, direct government intervention in business has been significantly reduced (Marquis & Qian, Reference Marquis and Qian2014). Fieldwork revealed that Chinese private entrepreneurs have the same robust incentives to generate a steady stream of profits over time as their counterparts in other countries (Krug & Mehta, Reference Krug, Mehta and Krug2004). When they believe that the obstacles will be gradually removed through marketization, those who understand the strategic value of HR (because of advanced education or advice from professional managers) will be more motivated to make HR development investments. This is because as autonomous agents shaping their organizational destinies (Child, Reference Child1997), they would view the improvement of government support as a valuable opportunity for private business and attempt to take advantage of it. For those who understand the strategic value of HR, HR development investment and the resulting discretionary effort from skilled and knowledgeable workers would become a rational choice for seizing the opportunities available within the environment (Astley & Van de Ven, Reference Astley and Van de Ven1983; Child, Reference Child1972, Reference Child1997). In sum, a positive perception of government support during a market transition will further stimulate HR development investment for private entrepreneurs who see the strategic value of their people (i.e., those who have a higher education level and have a complete governance team).

However, we do not expect that all private entrepreneurs will see government support for private business positively during the transition. The economic reform was initiated by the CCP to deal with failures of central planning within the institutional framework of state socialism (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012). There are always different voices about the direction of economic reforms in China. The debates of different voices may cause some pragmatic private entrepreneurs to become conservative about the ongoing market transition, particularly those who have been shocked by the anti-capitalist politics of the last few decades in China, which included the persecution of capitalists. They may worry about possible policy reversals and view the unpredictability of economic institutional arrangements under Communism as threats to their private property (Duckett, Reference Duckett2004; Wank, Reference Wank1999). Private entrepreneurs who do not trust the market transition may make pessimistic judgments about institutional support and the protection of property rights. In this situation, even when private entrepreneurs personally see the strategic value of HR, they may be reluctant to invest in HR because they see less benefit from such long-term investment. They instead become risk averse and make investments that give rapid returns, and avoid long-term investments such as HR development investment (Harrell-Cook & Ferris, Reference Harrell-Cook and Ferris1997; Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012; Tsang, Reference Tsang1996). Thus, when private entrepreneurs have a negative judgment about government support for private business during the market transition, the relationship between strategic choice variables and HR investment is weakened. We hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3a. Perceived government support for private business will positively moderate the relationship between private entrepreneurs’ education and HR development investment in private firms such that the relationship will be stronger when they perceive greater government support for private business.

Hypothesis 3b. Perceived government support for private business will positively moderate the relationship between governance team completeness and HR development investment in private firms such that the relationship will be stronger when private entrepreneurs perceive greater government support for private business.

As discussed above, a positive perception of government support in a market transition will stimulate private entrepreneurs’ confidence about the future of private business in China, enhancing the HR investment tendency of those who see the strategic value of HR. Different from such an enhancement logic, we expect that there is a substitution relationship between perceived government support for private business and institutional variables. This is because the effect of institutional variables on HR development investment is derived from the legitimacy need of domestic private firms. When private entrepreneurs perceive that government support for private business is improving, their need for and motivation to gain legitimacy and protection (e.g., through political affiliation) will decrease. Consequently, the effect of institutional variables should be reduced to some extent. However, we do not expect that the substitution effect will significantly change the relationship between institution-based variables and HR development investment. In other words, the negative moderation effect is not expected to be strong or significant. While pursing the market transition, the CCP has a natural motivation to sustain and enhance its power base and political control (Li, Meng, Wang, & Zhou, Reference Li, Meng, Wang and Zhou2008; Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012; Tsang, Reference Tsang1996). The current economic reform does not fundamentally challenge the orthodox status of the espoused Communist ideology in China. The private sector always experiences the pressure to gain sociopolitical legitimacy and mobilize public support. This pressure exists in the Chinese institutional context even when government support for private business improves. Therefore, perceived government support for private business is unlikely to fully substitute for institutional variables in terms of gaining sociopolitical legitimacy and public support through HR development investment.

METHOD

Sample

We used data from the Chinese Private Enterprise Survey to test our hypotheses. This survey is designed and administrated every two years jointly by the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, the United Front Work Department of the Central Committee of the CPC, and the China Society of Private Economy Research at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Respondents are the founders or principal investors of the firms. This survey has been frequently used in previous studies on Chinese private firms (Chen, Reference Chen2007; Li et al., Reference Li, Meng, Wang and Zhou2008; Ma & Parish, Reference Ma and Parish2006; Yiu, Wan, Ng, Chen, & Su, Reference Yiu, Wan, Ng, Chen and Su2014).

As discussed, private business is experiencing ideological and institutional discrimination during China's transition. After 2000, several significant improvements were made to the institutional environment for domestic private firms. In 2001, the CCP announced that private entrepreneurs would be allowed to join the Party. In March 2004, the NPC approved a constitutional amendment to protect private property rights. In 2005, the State Council pledged to grant private firms equal treatment with all other types of firms. Therefore, we chose the 2006 survey data to examine how private entrepreneurs perceived these institutional changes. The 2006 survey was designed to inquiry about the information of private firms in the year of 2005 from a representative sample of 3,837 firms from 30 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions in China. We retained 1793 observations, which provided information on HR investment in this study. The mean and standard deviation of our study variables before and after the sample selection were compared and the differences were found to be small and non-significant.

Measures

HR development investment

In this study, we used average training expense (thousands of Yuan per employee) to measure a private firm's investment in developing employees’ knowledge and skills in the year of 2005. Because the distributions of average training expense were positively skewed, we used a natural logarithmic transformation of this indicator in the following analyses. This indicator has been generally included in the measure of high-investment HRM practice (Lepak, Taylor, Tekleab, Marrone, & Cohen, Reference Lepak, Taylor, Tekleab, Marrone and Cohen2007; Shaw, Park, & Kim, Reference Shaw, Park and Kim2013). However, Shen (Reference Shen2010) found that employees are very dissatisfied with the poor organizational support for training and development opportunities in Chinese private firms.

Strategic choice variables

We included two strategic choice variables: (1) the education level of private entrepreneurs, which was measured using the number of years they have spent in formal educational institutions; and (2) governance team completeness, a dummy coded 1 if the firm had a complete managerial team of a board, managing director, and audit committee; and 0 otherwise.

Institutional variables

We measured this group of factors using two dummy-coded variables: (1) political affiliation: a dummy coded 1 if a private entrepreneur was a member of the PC or CPPCC and 0 otherwise; and (2) former state ownership: a dummy coded 1 if the private firm was restructured from a state-owned or collective-owned firm and 0 if it was founded as a private firm.

Perceived government support for private business

Private entrepreneurs were asked to evaluate six questions about the transition of economic institutions for private business. The questions included the following: (1) ‘relaxing restrictions on market entry’; (2) ‘legalizing private property and safeguarding the legitimate rights and interests of private firms’; (3) ‘improving government's service delivery and standardizing government charges’; (4) ‘providing government support for innovation in private firms’; (5) ‘promoting favorable public opinion atmosphere for private firms’; and (6) ‘implementation of favorable policy on private firms by local government’. A four-point Likert-type scale was used (1= ‘worsened’ to 4 = ‘significantly improved’). We factor analyzed the six questions using principal component extraction. The result provided a one-factor solution with an eigenvalue of 3.50, which explained 58.36 percent of the common variance among the items. Cronbach's α for the scale was 0.86.

Control variables

We controlled for the characteristics of private entrepreneurs that may influence HR development investment, including his/her age, gender (coded 1 if male and 0 if female), and the CCP membership (coded 1 if the answer was yes and 0 if the answer was no). Meanwhile, we also controlled for his/her personal learning to clearly examine the effect of educational attainment. It was measured as how many hours private entrepreneurs spend on informal learning each day (standardized for analyses).

In addition to private entrepreneurs’ attributes, we further controlled for firm-specific attributes. We controlled for firm size using a natural logarithmic transformation of the number of full-time employees and firm age calculated as 2006 minus the year the private firm was founded. Research finds that organizations are more likely to adopt legitimate practices if they have more resources (Park, Sine, & Tolbert, Reference Park, Sine and Tolbert2011). Since we had no objective measures of firm assets, we chose to control for this variable using a subjective question: Have the total net assets of your firm achieved constant growth in the past two years? (coded 1 if answer was yes and 0 if answer was no). In addition, we included firm donations as an alternative to obtaining sociopolitical legitimacy for domestic private firms (Ma & Parish, Reference Ma and Parish2006). It was measured as a natural logarithmic transformation of donation expenses in the year of 2005. Since firms were drawn from different industries, we controlled for industries (coded 1 for manufacturing and 0 for non-manufacturing). Finally, because there are considerable differences in economical and institutional development across China (Marquis & Qian, Reference Marquis and Qian2014), we controlled for firm location (dummy variable, 1 for urban area and 0 for rural area) and region (dummy coded with coastal provinces as the reference group).

RESULTS

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics and correlations of our study variables. As shown, both of the strategic choice variables are significantly related to average training expense (for private entrepreneurs’ education, r = 0.16, p < 0.01; for governance team completeness, r = 0.09, p < 0.01). Between the two institutional factors, while political affiliation was significantly related to average training expense (r = 0.06, p < 0.01), former state ownership was not (r = -0.02, n.s.). Furthermore, perceived government support for private business was positively related to average training expense (r = 0.06, p < 0.01). However, it was not significantly correlated with all of the predicting variables.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations among the variables in this study

Notes: N=1789. † p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, two-tailed tests. Average training expense is counted by thousands of Yuan per employee. For gender, 1= male and 0 = female; for location, 1= urban and 0 = rural; for industry, 1 = the manufacturing industry and 0 = others. The referent group for the region is coastal provinces.

In this study, the dependent variable of average training expense has a number of its values clustered at a truncating value (zero in our data). We therefore used the Tobit model to test the hypotheses. This technique is preferred because it uses all observations, both at and above the limit, to estimate a regression line (McDonald & Moffitt, Reference McDonald and Moffitt1980). Table 2 presents the regression results.

Table 2. Tobit regression analyses on average training expenses

Notes: † p <.10, *p < .05, **p < .01, two-tailed tests. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. Average training expense is counted by thousands of Yuan per employee. For gender, 1= male and 0 = female; for location, 1= urban and 0 = rural; for industry, 1 = the manufacturing industry and 0 = others. The referent group for the region is coastal provinces.

Both Hypothesis 1a and 1b predict that strategic choice variables are positively related to HR development investment. To test the two hypotheses, we first included private entrepreneurs’ education in Model 1, and then included governance team completeness in Model 2. As shown in Table 2, both of the strategic choice variables had positive and significant relationships with average training expense (for private entrepreneurs’ education β = 0.01, s.e. = 0.00; p < 0.01, while for governance team completeness β = 0.06, s.e. = 0.01; p < 0.01). Thus, both Hypothesis 1a and 1b received support.

Hypothesis 2a and 2b predict positive relationships between institutional factors and HR development investment after controlling for strategic choice variables and the characteristics of private entrepreneurs and firm-specific variables. As shown in Model 3 of Table 2, after controlling for the two strategic choice variables, political affiliation remained significantly related to average training expense (β = 0.02, s.e. = 0.01, p < 0.05). However, as shown in Model 4, the effect of former state ownership was not significant for average training expense (β = 0.01, s.e. = 0.02, n.s.). Therefore, Hypothesis 2a was supported, while Hypothesis 2b was not supported.

Hypothesis 3a and 3b propose that perceived government support for private business moderates the relationship between strategic choice variables and HR development investment. We used moderated regression procedures to test such hypotheses. We entered control variables in Step 1, both strategic choice and institutional variables, and perceived government support in Step 2, and their product terms in Step 3. As shown in Model 7 of Table 2, the results from the Tobit model show that two product terms were positively related to average training expense: the interaction between private entrepreneur's education and perceived government support for private business (β = 0.01, s.e. = 0.00, p < 0.05), and the interaction between governance team completeness and perceived government support for private business (β = 0.06, s.e. = 0.03, p < 0.05). Inconsistent with our prediction, the interaction between former state ownership and perceived government support for private business was negatively significant for average training expense (β = -0.06, s.e. = 0.03, p < 0.05, Table 2, Model 9). In order to test the robustness of our findings, we included all the interaction terms in Model 11 and all the relationships remained the same without significant changes.

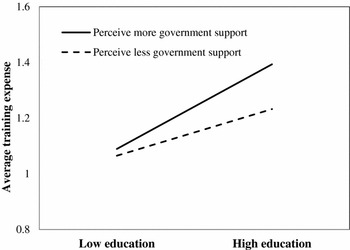

We plotted the significant interactions between our strategic choice variables and perceived government support in Figure 1 and 2. As shown, perceived government support for private business strengthened the relationship between private entrepreneurs’ education and average training expense (Figure 1), and the relationship between governance team completeness and average training expense (Figure 2). Taken together, both Hypothesis 3a and H3b received support.

Figure 1. Interaction effect of private entrepreneur’ education and perceived government support for private business on average training expenses

Figure 2. Interaction effect of governance team completeness and perceived government support for private business on average training expense

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provided a contextualized analysis of HR development investment in Chinese private firms using survey data from a nationally representative sample. We found that strategic choice variables (private entrepreneurs’ education and governance team completeness) were positively related to HR development investment. These relationships were stronger when private entrepreneurs had a positive perception of government support for private business during the transition of economic institutions. Furthermore, institutional variables (i.e., political affiliation) remained significant for HR development investment after controlling for strategic choice variables. Perceived government support negatively moderated the relationship between former state ownership and HR development investment. These findings provide meaningful theoretical and policy implications.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

First, this study extends previous HR research by identifying the specific characteristics of key decision-makers that matter for HR-related investment as a strategic choice of the firms. Derived from the basic principle of SHRM which views employees as valuable resources for firms, HR scholars contend that one precondition for HR-related investment is that top management recognizes HR as a strategic asset (Kaufman & Miller, Reference Kaufman and Miller2011; Wei & Lau, Reference Wei and Lau2005). In order to test such ideas, researchers primarily focused on variables such as HRM importance, organizational strategy, and environmental pressures, to explain why some firms were more likely to invest in HR than others (Ordiz-Fuertes & Fernández-Sánchez, Reference Ordiz-Fuertes and Fernandez-Sanchez2003; Pil & MacDuffie, Reference Pil and MacDuffie1996; Som, Reference Som2007; Thompson & Heron, Reference Thompson and Heron2005; Wei & Lau, Reference Wei and Lau2005). The characteristics of key decision makers are largely ignored in this line of research. Building on the strategic choice perspective (Child, Reference Child1997), our results demonstrated that private entrepreneurs, those who are well educated and receive professional support from their team, tend to invest in training and developing employees’ skills and remedying their skill deficiencies in an economy becoming more knowledge based. Thus, investment in developing and maintaining a skilled and productive workforce is an example of how private entrepreneurs take strategic action in a transitional economy. Therefore, our findings help illuminate why some private entrepreneurs engage in HR-related investment and proactively respond to the market transition in China. This fine-grained knowledge further helps us understand the micro-foundations of the market transition in China.

Second, this study incorporated the institutional perspective into the contextualized analysis of HR development investment in Chinese private firms. Although the institutional perspective has been used to explain the adoption of certain management practices (Palmer, Jennings, & Zhou, Reference Palmer, Jennings and Zhou1993; Teo, Wei, & Benbasat, Reference Teo, Wei and Benbasat2003; Westphal, Gulati, & Shortell, Reference Westphal, Gulati and Shortell1997), HRM researchers made few references to institutional theory until the early 1990s. In their influential paper on SHRM, Wright and McMahan (Reference Wright and McMahan1992) argue: ‘the idea of institutionalization may help in understanding the determinants of HRM practices’ (313). Since then, institutional theory has primarily been applied to compare HRM practices across different countries/institutional environments. Mainstream SHRM research gave less attention to the potential influence of institutional variables. Recognizing this limitation, HR researchers have called for the application of institutional theory to better understand HR-related decisions within a single institutional framework (Boon et al., Reference Boon, Paauwe, Boselie and Den Hartog2009; Kim & Wright, Reference Kim and Wright2011; Paauwe & Boselie, Reference Paauwe and Boselie2005).

As a direct response to this call, our paper included institutional variables and found that political affiliation explained additional variance in HR development investment beyond strategic choice variables in domestic private firms. In order to gain sociopolitical legitimacy and alleviate institutional discrimination in the Chinese market, our findings suggest that private entrepreneurs not only act as strategists (to gain competitive advantage in market competition), but also as politicians (to gain legitimacy in the socio-political arena). HR development investment has become a tool entrepreneurs use to manage their relationships with stakeholders such as employees, the government, and the public. Experiencing massive institutional changes, private firms provide a valuable opportunity to demonstrate the effect of external institutions on HR development investment. The inclusion of external institutional variables not only explains the rationality behind HR development investment, but also contributes to our knowledge about the variations in HR practices among firms within a single institutional framework (Kaufman & Miller, Reference Kaufman and Miller2011). However, the effect of institutional variables on HR development investment should draw our attention, because such investment may be pragmatic in nature. Private entrepreneurs may withdraw their investment when they perceive less value of such an investment in pursing their sociopolitical legitimacy. Without a long-term vision, HR planning and systems in private firms may be inconsistent and lack sustainability. The right way to encourage HR development investment is to make private entrepreneurs understand the strategic value of their people for their long-term business success.

Third, by examining perceived government support for private business as a boundary condition, our results demonstrate the interaction between individual actors and the institutional environment in which they are embedded. The transition of economic institutions in China is gradual and experimental. An ambiguous institutional environment allows opportunities for strategic and agentic behavior for actors with foresight (Scott, Reference Scott2008). Viewing managers as proactive and autonomous, strategic choice theorists view the environment as information flows, which can be interpreted, made sense of, and responded to by organizational leaders (Gopalakrishnan & Dugal, Reference Gopalakrishnan and Dugal1998). Consistent with this view, our results suggest that a positive evaluation of the transition of market supporting institutions significantly enhanced the tendency of private entrepreneurs who see the strategic value of their employees to make HR development investments. Together with the main effects of strategic choice variables, our findings about their interaction with the evaluation of market transitions further illustrate how private entrepreneurs take deliberate and proactive actions to enhance their long-term competitive advantage as simple, low cost manufacturing is gradually being replaced by higher quality, sophisticated products and complex manufacturing during the market transition in China. Therefore, our findings are important for SHRM theory and research because they extend the contingency perspective by revealing economic institutional influences as an important contingency factor in understanding HR-related decisions. Meanwhile, such an exploration would also advance our knowledge about the interaction between individual strategic actors and their institutional environment, and demonstrate how decision makers make rational choices to modify and construct options available within the environment through mobilizing their resources (Child, Reference Child1972; Reference Child1997).

Consistent with our expectation, there was no negative moderating effect of perceived government support for the relationship between political affiliation and HR development investment. This suggests that one's current political affiliation continues to exert institutional influences on HR development investment. In other words, improving market supporting institutions can drive HR development investment, but cannot significantly substitute the effect of political affiliation. However, we noticed a significant negative moderating effect in the case of former state ownership. This finding deserves our attention, because it suggests that private firms may significantly modify their historical imprints and adjust their HR practices when they perceive improving market supporting institutions. Future research should examine under which conditions private firms (restructured from SOEs) may diverge from the imprint of Communist ideology. Such an exploration would enable us to know more about what is happening in China and contribute to our knowledge about the transition in emerging economies (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012; Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson, & Peng, Reference Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson and Peng2005).

Finally, this study offers important policy implications for emerging economies. Most emerging economies have weaker institutions, including poorly functioning markets, incomplete private property rights, and a poor legal foundation. Weak institutions may dampen the enthusiasm of private entrepreneurs and reduce their interest in making long-term investments, such as HR development investment (Krug & Mehta, Reference Krug, Mehta and Krug2004; Tan, Reference Tan1996). Therefore, many emerging economies, including China, have increasingly accelerated their market transition. They realize that the long-term sustainable growth relies on product development and innovation (which requires HR development investment) rather than on imitation and low cost production. Considering that a market transition usually takes a long time to complete, our study suggests that it is critical to win the trust of business entrepreneurs during this process. If they have doubts about this transition, they may focus only on short-term interests and their entrepreneurship may be inhibited, reducing HR development investment even when they see the strategic value of HR for the future. The process of entrepreneurship in emerging economies is a collective achievement requiring both the enthusiasm of individual entrepreneurs and the governments’ persistence in market transition.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This research has limitations that point to future research directions. First, the study focuses on both the strategic choice and institutional perspectives to explain HR development investment in domestic private firms. Because of data constraints, we did not include any culture-specific variables. However, there is a long tradition in Chinese capitalism of providing employees with ‘fatherly concern or considerateness’ (Redding, Reference Redding1990). Such a paternalistic culture may be another factor in explaining HR development investment in domestic private firms (Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Zhang and Shen2012). Future research should examine this possibility.

Second, this study is cross-sectional in nature. In order to establish causality among variables, we carefully chose independent variables to ensure temporal separation from dependent variables. For example, our theory is that former state ownership creates an institutional legacy, thus leading to more HR development investment. There is no conceptual reason to believe that HR development investment causes a change in a firm's ownership. Similarly, either PC or CPPCC memberships already existed before HR development investment was made in the data collection year. HR development investment was measured at the end of 2005. Because the term of PC/CPPCC membership was from 2003 to 2008, it was unlikely that private entrepreneurs earned their PC/CPPCC membership in 2005 due to their HR development investment in 2005. Future research may examine the possibility that private entrepreneurs invest more in HR development in order to increase the odds of being elected to the PC/CPPCC in the future. Similarly, the cross-sectional data cannot rule out the possibility that PC/CPPCC members may have a more favorable view of government support. Empirically, the correlation between perceived government support and PC/CPPCC membership is only 0.03 in this study. This result suggests that private entrepreneurs who are PC/CPPCC members may not necessarily have a more favorable assessment of government progress in leveling the playing field for private firms in an anonymous survey. However, we do encourage future research to address the causality among those variables using longitudinal data.

CONCLUSION

We provide a contextualized analysis of HR development investment in Chinese domestic private firms. While the effect of institution-related variables on HR development investment was partially supported, the strategic choice perspective received general support, including the main effect of strategic choice variables and their interactions with perceived government support for private business. We found that for private entrepreneurs who see the strategic value of HR, their perceptions of the transition (improvement) of economic institutions are critical in strengthening their tendency to make greater HR development investments. Governments in transitional economies should strengthen their market and legal systems to increase the willingness of private firms to make HR development investment. We hope that our research will drive future research on HR issues that contextualize firm behaviors in their unique institutional environment.