Background

Almost 20% of the UK population over 16 years of age experience symptoms of depression or anxiety, with significant costs to individuals, families and society (Mental Health Foundation, 2016). Within this population access to, and outcomes from, mental health care are not currently equitable (Sproston and Nazroo, Reference Sproston and Nazroo2002). There is evidence of professional uncertainty among practitioners about how to engage with ethnic and religious diversity (Kai et al., Reference Kai, Beavan, Faull, Dodson, Gill and Beighton2007), and concerns about inequitable provision among commissioners (Salway et al., Reference Salway, Mir, Turner, Ellison, Carter and Gerrish2016). Among minority ethnic clients, research highlights low levels of trust in mental health services and widespread failure to accommodate spiritual needs in National Health Service (NHS) care (Mir and Sheikh, Reference Mir and Sheikh2010; NICE, 2016). In the context of ethnic and religious diversity in the UK, such persistently poor outcomes indicate that, despite pockets of progress, these inequalities remain a priority area. Interventions are needed to increase equity of access and reduce the personal as well as social costs of depression, including NHS and welfare benefit costs and loss in productivity such as time taken off work (Mental Health Foundation, 2016).

NICE guidance on depression and Department of Health policy encourages sensitivity to variations in cultural background, which significantly affect treatment outcomes (Department of Health, 2005; NICE, 2016), but little evidence exists on how to achieve this in practice. In recognition of the nationally identified need for culturally adapted therapies, G.M., S.M. and colleagues at the Universities of Leeds and York collaborated with Bradford District Care Trust and Sharing Voices, Bradford to develop and pilot an adapted therapy for Muslim clients. This was based on behavioural activation (BA), an existing evidence-based psychosocial treatment for depression (Ekers et al., Reference Ekers, Webster, Van Straten, Cuijpers, Richards and Gilbody2014; Lejuez et al., Reference Lejuez, Hopko, Acierno, Daughters and Pagoto2011; Martell et al., Reference Martell, Addis and Jacobson2001) that explicitly focuses on client values and links these to behavioural goals. In a systematic review of randomized trials, BA was comparable to cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) in reducing symptoms of depression at post-treatment and follow-up (Lejuez et al., Reference Lejuez, Hopko, Acierno, Daughters and Pagoto2011). The focus on client values in this therapy makes BA a particularly suitable treatment for cultural adaptation and it has been successfully adapted and tailored to multiple cultural contexts across the globe (Kanter and Puspitasari, Reference Kanter and Puspitasari2016; Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Santiago-Rivera, Santos, Nagy, López and Hurtado2015; Moradveisi et al., Reference Moradveisi, Huibers, Renner, Arasteh and Arntz2013). A pilot study of adapted BA for Muslim clients from diverse ethnic backgrounds and sects found the adapted therapy was acceptable to patients and therapists and feasible in Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) settings (Mir et al., Reference Mir, Meer, Cottrell, McMillan, House and Kanter2015). This paper addresses some of the issues that need to be addressed for this culturally adapted approach to be adopted routinely in IAPT and other mental health services, including under-referral of targeted service users, limited therapist confidence to engage with diverse cultural groups and a need for more individual and system support in relation to access and engagement.

Why Muslims?

The need for an intervention specifically targeting Muslim populations is highlighted by the higher levels and longer term depression that have been found among sub-groups of Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities compared with the general population (Sproston and Nazroo, Reference Sproston and Nazroo2002). These communities are predominantly Muslim and our analysis of routinely collected national IAPT data (IAPT Data Set Reports, 2018) provides evidence that this faith group is under-represented in therapy services; IAPT data nationally show that 2% of clients are Muslim although they formed 5% of the population of England and Wales in 2011 (Office for National Statistics, 2013). Furthermore, these data also confirm under-referral of Muslim communities to therapy services. We analysed data for six sites, most of which had a much higher proportion of Muslims (e.g. 25 and 19%) than the national 5% figure. We found only 3% Muslim referrals at these sites (n = 625) compared with the 8% (n = 1579) figure that should be expected based on Census 2011 data. There were also considerably poorer recovery rates for Muslims compared with the general population at these sites. Analysis elsewhere has shown similar patterns for Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) groups nationally (Carter, Reference Carter2017), indicating that cultural adaptations for other minority ethnic and religious groups are also needed.

Muslim clients are more likely to use religious coping techniques than individuals from other religious groups in the UK and least likely to say they would seek professional help for depression (Loewenthal et al., Reference Loewenthal, Cinnirella, Evdoka and Murphy2001). Faith identity is therefore a potentially important focus for culturally appropriate mental health treatments in this group. There is a significant body of literature which shows that religion may influence wellbeing through pathways that are behavioural, psychological, social and physiological (Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, King and Carson2012). Interventions that draw on faith can be effective in addressing and preventing depression (Lipsker and Oordt, Reference Lipsker and Oordt1990) and improving quality of life (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Czaja and Schulz2010). Religious coping strategies for depression have been integrated into CBT, counselling, acceptance and commitment therapy, and energy psychology approaches as well as treatment of depression in cancer and terminally ill patients and those who have experienced trauma and torture (Mir et al., Reference Mir, Kanter and Meer2013).

The literature on religion and mental health identifies a distinction between ‘negative religious coping’, i.e. feeling abandoned or punished by God or unsupported by one’s religious community, and ‘positive religious coping’. The former can increase depression and anxiety (Dew et al., Reference Dew, Daniel, Goldstone and Koenig2008) and pain severity for people with physical illnesses (Cole, Reference Cole1999). ‘Positive religious coping’, on the other hand, is associated with reduced levels of depression and the use of an internalized spiritual belief system to provide strategies that promote hope and resilience (Carter, Reference Carter2017; Pargament et al., Reference Pargament, Tarakeshwar, Ellison and Wulff2001). Religious beliefs and practices that encourage a proactive approach to dealing with problems, rather than relying on divine intervention, are also more likely to help people overcome depression (Uchendu, Reference Uchendu2006).

Reviews of religious and spiritual therapies for depression have shown that studies incorporating religious components into therapy can have positive results and that adapted therapies can be at least as effective as existing secular therapies. For Muslim clients, such therapies have also resulted in earlier improvements in depressive symptoms (Hook et al., Reference Hook, Worthington, Davis, Jennings, Gartner and Hook2010). Psychotherapy and religious teachings can therefore be seen as complementary rather than competing approaches to overcoming depression (Wright and Basco, Reference Wright and Basco2001). It is suggested that the effectiveness of spiritually focused therapy is achieved through its ability to provide meaning, a sense of wellbeing, social support and the use of positive self-talk, as well as to the act of surrendering control to a higher power (Lipsker and Oordt, Reference Lipsker and Oordt1990).

Within Muslim communities, there is a dual potential for faith identity to act as both a resource for health and a trigger for social exclusion (Moradveisi et al., Reference Moradveisi, Huibers, Renner, Arasteh and Arntz2013). As a prime identity, religion is often drawn on by Muslims as a resource for health (Office for National Stastistics, 2013). However, faith-sensitive approaches are not routine and implementation barriers indicate a need for initiatives that combine adjustments to therapy with action at community level to improve access and consistent delivery (Wilson, Reference Wilson2009). The intervention supports therapists to engage positively and reflexively with a group that routinely experiences high levels of negative social and media misrepresentation and widespread racism (Bayraklı and Hafez, Reference Bayraklı and Hafez2016).

Current evidence relating to cultural adaptation of therapy for this population is sparse and has focused on CBT. Our study complements work that has sought to provide culturally adapted treatments for predominantly Muslim populations (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Munshi, Rathod, Ayub and Gobbi2015; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008) adding a specific focus on assessing and incorporating religious beliefs and values as part of treatment where this is helpful.

As well as helping to fill a current gap in evidence relating to mental health and religious identity, the adapted therapy recognizes the broader cultural identities of Muslim clients. Issues such as stigma, collective family structures and supernatural explanations for depression are also covered within the resources produced, and best practice approaches that therapists can adopt are identified.

Therapy resources

Methods for developing and piloting the adapted therapy are described elsewhere, along with findings from the pilot study (Mir et al., Reference Mir, Meer, Cottrell, McMillan, House and Kanter2015). The approach involves use of a therapist manual that incorporates evidence-based approaches to engaging with Muslim clients with depression. A self-help booklet bringing together Islamic teachings that support and reinforce therapeutic goals has also been developed for use by clients choosing the adapted therapy and therapists working with them (Shabbir et al., Reference Shabbir, Mir, Meer and Wardak2013). The booklet is available in Urdu and Arabic as well as English, and a Turkish translation is also being developed. Therapists are advised to use routine procedures for engaging with clients who have limited English fluency, such as bilingual interpreters.

Use of these resources in practice has the potential to increase early access to a culturally appropriate treatment that could improve treatment outcomes and prevent long-term depression for Muslim clients. This approach also serves as a model for other disadvantaged populations that experience mental health inequalities. Muslim communities are the most ethnically diverse of UK religious groups (Office for National Statistics, 2013), and this, combined with the broad evidence base on diverse religious traditions from which the intervention has been developed, suggests that the model used is potentially transferable to a range of other faith groups.

This work has stimulated widespread interest in the potential for the culturally tailored approach to increase access to talking therapies and reduce the stigma attached to help-seeking in BME groups. Such interest has been identified from both primary care mental health teams, voluntary sector organizations, health policymakers, academics, students and media organizations, in the UK as well as internationally.Footnote 1 As the second largest and fastest growing religious group globally, it is not surprising that a culturally tailored approach should be seen as relevant in many international contexts where Muslims form the majority population. Teams wishing to enhance their current service offered recognize that the approach builds on an existing evidence-based treatment, has been developed through a robust process and aligns closely with UK and international mental health policy (Moradveisi et al., Reference Moradveisi, Huibers, Renner, Arasteh and Arntz2013).

Free training has been offered to a number of IAPT teams in the UK already and funding has been sought to support delivery in the voluntary sector, where expertise in engaging with minority ethnic and religious groups is more likely to be found. Existing evidence on BA indicates that, with adequate training, non-specialist delivery of the approach can achieve similar outcomes to those of specialist staff (Ekers et al., Reference Ekers, Richards, McMillan, Bland and Gilbody2011). This opens up the further potential for delivery in low resource settings such as refugee camps, where Muslims often form a significant proportion, if not the majority of camp residents.

Delivery in practice: Touchstone, Leeds

Client engagement with the Adapted-BA model

The team of therapists and supervisors at Touchstone, an IAPT commissioned BME mental health service provider within the Leeds voluntary sector, is one of a number of IAPT teams to have been trained to deliver the culturally adapted approach. The training is helpful in raising awareness of how religious coping can help a client with depression, for example, how Islamic teachings promote proactive behaviour in response to problems and can provide hope to counter despair or hopelessness linked to depression. The training also helps therapists to be more self-aware of their assumptions, about religion in general and Islam or Muslims in particular, and encourages a patient-centred approach that actively recognizes the social stigma that Muslims often face in the UK and globally. Eight of the nine therapists who provided feedback for the training event at Touchstone, for example, agreed or strongly agreed that the training had made them more aware of issues related to working with Muslim clients and that they felt better equipped to work with such clients. Open text comments from participants about the value of the training included:

‘I feel more confident in making space and giving permission to talk about religion.’

‘Knowing the difference between religion and culture. Making parallels to non-religious examples and how to deal with issues in other ways.’

‘The training has given me more confidence in working with Muslim clients.’

Ideas to improve the course included refocusing the case studies used and having more time to cover the content, although time was necessarily constrained by organizational considerations.

In practice, clients often present explaining that the main obstacle they face is feeling overwhelmed by their situation. Typically the client will attempt to cope with symptoms (e.g. tiredness, feeling low, little interest, hopelessness) by staying at home. As in standard BA, therapists will explain the BA model and the idea of an ‘outside-in’ approach. This encourages clients to engage in activities as a means of changing the way they feel rather than waiting to feel better before becoming active. The therapist will explain that ‘activating’ a valued behaviour, such as walking, is likely to bring about a reduction of symptoms and more motivation to walk. This improvement is less likely to happen if they simply wait for a reduction in symptoms before engaging with the valued behaviours (Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Manos, Bowe, Baruch, Busch and Rusch2010).

It is unlikely that clients will have considered their situation in this way previously; use of the BA model helps breaks the typical cycle of avoidance and rumination that leads to a lower level of positive reinforcement. This model supports higher levels of positive reinforcement and can support more enthusiasm for keeping up with helpful behaviour. Even the act of putting together a plan that incorporates some valued behaviours into usual routine often leads to some positive reinforcement and empowerment by virtue of clients exercising some control over their situation. Rumination is dealt with as an unhelpful behaviour in this approach, that can be limited and replaced with proactive and helpful behaviours that are in line with client goals.

In standard BA, the therapist is able to offer a graded approach and support to start with a small and consistent activity. This approach is reinforced by Adapted-BA through an Islamic teaching mentioned in the self-help booklet, which recommends small but regular actions. Another useful and complementary Prophetic teaching encourages the client to take an active role in their life rather than adopting a passive reliance on God. This teaching reinforces the BA position that change begins with the individual (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Extracts from the client self-help booklet.

Values and Adapted-BA

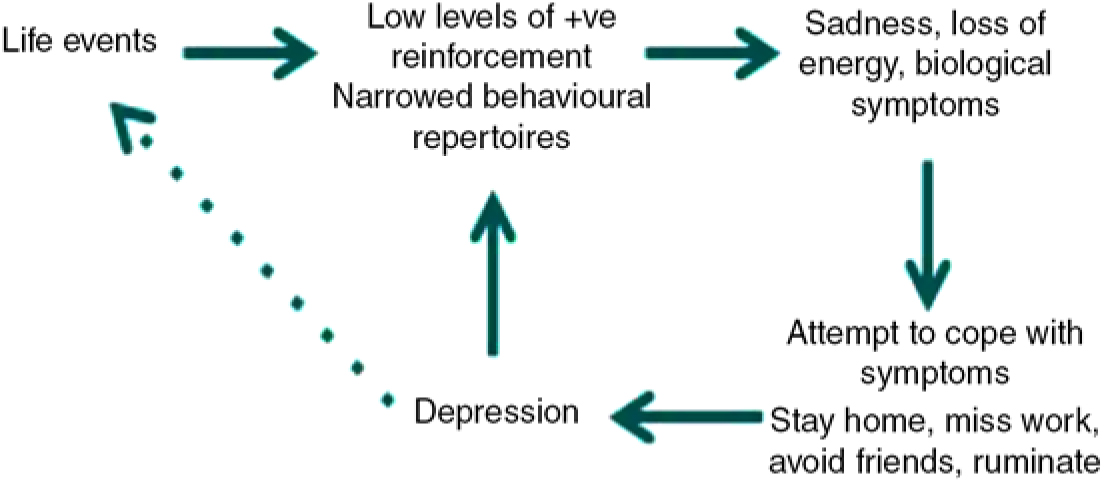

BA has a very straightforward rationale: people are more likely to become depressed when there are more difficult events in their lives. Difficult life events may be major losses like the end of a relationship, the loss of a job, or a move to a new city. Difficult events may be interpersonal difficulties including a lack of friends, or conflicts with friends or family members, daily hassles arising from a promotion that leads to too many responsibilities, inability to pay the bills, confusion about how to use public transportation and experiences of racism or discrimination.

The more difficult events one experiences in one’s life, the more likely one is to become depressed. When a client becomes depressed, he or she may give up, get stuck, become hopeless, become passive and inactive in life. He or she stops putting in real effort to solve problems and stops doing activities that used to be pleasant, meaningful and enjoyable. Individuals may even stop taking care of themselves, showering and brushing teeth, or getting out of bed. All of these changes may result in the depression getting worse, which starts a vicious cycle of depression (Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Santiago-Rivera, Santos, Nagy, López and Hurtado2015).

The BA model also refers to negative and positive reinforcement (Martell et al., Reference Martell, Addis and Jacobson2001). Negative reinforcement occurs if a behaviour is followed by an unpleasant consequence ceasing (or reducing), which then leads the client to increase that behaviour (see Fig. 2). This can result in short-term gain, such as a reduction or avoidance of unpleasant thoughts and feelings. However, a long-term loss may also result when the individual stops behaviours that are meaningful and important to the person, such as engaging with family members or friends. If behaviours are linked to values, then the individual may be more likely to persist in these meaningful behaviours even in the face of initial unpleasant thoughts and feelings. A values assessment can help identify behaviours that are likely to be positively reinforced because they are meaningful and linked to the client’s values.

Figure 2. Negative reinforcement.

A values assessment should be standard practice in BA as the BA model promotes a focus on ‘value consistent behaviours’. In Adapted-BA the Values Assessment is an extremely important early exercise in therapy during which space is created for the client to express what is important and gives meaning to his or her life. The assessment focuses on the individual and should not be hurried or omitted from initial or early sessions. It is introduced to clients with a rationale explaining its function, e.g.:

‘Depression can mean we do things in the short-term that make us feel a bit better, but in the long-run these things can keep depression going.’

‘Thinking about values can help identify behaviours that when done in the long run protect against depression.’

For Adapted-BA, a tool in the manual graphically representing different values that are important to most people includes religion and spirituality (Walser and Westrup, Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2007). Therapists will make it clear that perhaps not all areas in the values assessment will be relevant, emphasizing that there are no right or wrong values. Just as not all areas of the diagram will be relevant to all clients, religion and spirituality will not be important or relevant to all Muslim clients and the tool allows clients to omit as well as include religion as a value.

Therapist acceptance of a client’s values, including religious beliefs, in a non-critical way is essential to developing trust and open discussion. Creating a safe space for clients to say that religion is important to them or to omit religion from their identified values is essential for therapists from any background. While it should not be assumed that religion will be important to all clients, therapists should be aware that for those that have had a Muslim upbringing religion could still have influenced their relationships with family and community members in some way and may still be relevant to therapy. In cases where a client is ambivalent about religion or religious understanding and experience are contributing to depression, links with a religious expert can be helpful to therapists. Touchstone has established links with the imam and a female lead at Leeds Grand Mosque to support collaboration in such cases.

Broader cultural issues beyond religion such as stigma, family dynamics and supernatural understandings of depression can be discussed in Adapted-BA and may be raised in relation to the values assessment. Touchstone practice, drawing on this assessment, is to encourage clients to explore proactive and helpful behaviours in line with their values. For example, some clients have brought their spouses to sessions to help challenge family shame about depression or cultural stigma and this has created an opportunity to enlist family support for therapy and help with homework tasks. There is often overlap between these broader cultural issues and religion: religious teachings can be a powerful tool to challenge stigma and can empower clients by supporting their position in a situation over which they may have limited control. Similarly, clients worried about evil forces behind their ill health can draw on teachings about protection through specific prayers which are mentioned in the self-help booklet.

Religious coping

A range of triggers (often referred to as ‘negative life events’) such as bereavement, relationship breakdown, or illnesses can lead to symptoms of depression. Religious individuals may conceptualize such difficulties as a punishment from God, which can lead to guilt as well as passive and hopeless feelings about their situation. However, the manual and booklet refer to a teaching that encourages the client to think about difficulties as life tests rather than punishments. A common belief that some Muslims have is that feeling depressed means that they are not devout enough as a Muslim or that they have low levels of faith. The manual helps the client to understand that feeling depressed does not mean that they have failed as a Muslim, and encourages hope in the Mercy of God, and that difficult life events are tests. From a clinical perspective, acknowledging the benefits of religious belief can help reduce the community stigma that may be attached to seeking support from outside the religious group involved.

Treatment outcomes

The main treatment outcomes sought are a reduction in depressive symptoms on all measures used in relation to Adapted-BA: the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS: Mundt et al., Reference Mundt, Marks, Shear and Greist2002); the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9: Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) and the Behavioural Activation for Depression Scale (BADS-SF: Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Mulick, Busch, Berlin and Martell2007). The latter measure was developed specifically for BA and has been used in a version of BA adapted for Latino clients in the US (Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Santiago-Rivera, Santos, Nagy, López and Hurtado2015). The pilot study for Adapted-BA in the UK explored appropriateness of PHQ-9 and WSAS measures, as they are routinely used in IAPT services in the UK. Feedback from service users was that the measures were acceptable but an introductory statement about the need to ask about suicidal feelings would help, given that suicide is forbidden in Islam and may be more difficult to discuss.

The following case studies relate to use of the culturally adapted approach at Touchstone by R.G. and G.H. Case study clients volunteered to give feedback, an opportunity offered to all clients at the end of therapy as a way of achieving service user involvement in improving the service. All Touchstone clients are offered this opportunity to provide feedback by email or post through a separate administrative process that does not involve their therapist and in which they are not required to identify their therapist. Feedback to the service from clients receiving Adapted-BA has not indicated any negative reactions, although some Muslim clients may decide to take the booklet but not use the approach in therapy. This can sometimes be because they feel they know the religious teachings well and do not need support to draw on them or because they wish to keep their religious activity private and work on other areas of the value based goals. Some people have also decided to work on the self-help booklet themselves and focus on other issues in therapy.

Case study 1

The client had experienced the loss of her father two years previously. She also began to experience difficulties at work and found that during this time she began to pray less and found her usual activities more difficult. She began to consider these difficulties as a punishment from God.

The client was off sick from work and started to feel as though she was a bad mother as well as a bad person and bad Muslim. She had sought therapy at the time of her father’s death and had completed a full course of CBT, experiencing some benefits that had not been sustained and she felt that standard CBT had been like ‘half a journey’ to her. When she sought help again 2 years later from Touchstone she was offered the Adapted-BA therapy. The client started to use the self-help booklet and felt that her life began to change. She focused on Quranic teachings that helped her to reflect and accept that hardships can be a test. These teachings also encouraged her to have hope and relief from the difficulties and symptoms she was experiencing. The approach helped her to focus more on Allah’s Mercy than on the idea of being punished. Focusing on teachings that Allah is Merciful and therefore we should show ourselves mercy contributed towards an increase in her self-esteem and self-confidence.

At the end of the course of Adapted-BA therapy this client gave feedback that the approach was more meaningful to her than her previous therapy and that she was able to talk about all aspects of her identity and speak about her values related to being a Muslim in an open and beneficial way. She felt able to be more active, in line with her values, by focusing on her life experiences as a test. This resulted in a reduction in rumination and greater hopefulness about the future. The client was also supported to draw on religious teachings in order to reframe her negative interpretation of the concept of ‘sabr’ (patience), which she originally interpreted as having to live with whatever difficulties she experienced. Alternative teachings, particularly about taking responsibility for her situation (see Fig. 1) helped her realize she could improve her situation and needed to take responsibility for doing this rather than passively relying on God to resolve her difficulties. This more active interpretation of ‘sabr’ as ‘persistence despite adversity’ also contributed to her feeling more hopeful.

The client felt empowered in setting her own life goals through gaining a more positive and in-depth understanding of various Prophetic teachings. She established routine religious behaviours, such as reading specific prayers, that empowered her to carry out planned activities that had previously been difficult for her. These supplications confirmed for her the meaning of her life and helped her to focus on hopefulness. In addition, she also began to give herself permission to allow herself to carry out enjoyable activities and not feel guilty about enjoying these. This more compassionate position towards herself meant she did not berate herself if she was not able to achieve every change. The client drew on the ‘one step at a time’ religious approach in the client booklet which she felt had equipped her with tools that she could use for recovery.

Case study 2

This male, 48-year-old client had been divorced for 9 months from his wife and became depressed as he was not granted access to see his children and missed them a lot. He described his faith as important to him but that he had become distant from religious practice due to feelings of despair – feeling life was unfair, and feeling hopeless. He had stopped doing most of his routine activities and all of his pleasurable activities and had become isolated as he had stopped socializing.

He first looked at his goals relating to areas of the values assessment tool and made changes to them, drawing on the religious teachings in the self-help booklet. The teachings helped him to see being proactive as in line with his religious beliefs. He could see he was stuck in a vicious cycle of depression where his avoidance and lack of pleasure or achievement were making him more depressed.

He started scheduling to go into work at structured times, instead of when he felt like it, and made lists of things to do at work that he had been putting off, starting with the easiest to achieve and making sure he was not putting too much in his day. This graded approach to change was again reinforced through religious teachings in the booklet. He then started attending his cricket club again as he used to enjoy this and had lost contact with friends and soon made new friends. He was tidying up at home and cooking a couple of days a week again, which also helped him feel better.

He spent most of the night staying awake and ruminating about the past but was able to challenge his negative thoughts using a defusion technique: when he found himself ruminating he would use relaxation techniques and read messages on an Islamic Whatsapp group that was full of religious reminders and support which helped him ruminate less and get better sleep.

After the positive reinforcement and change in these areas, he explored his religious goals specifically on the values assessment. He started going to Friday prayers and reconnecting with his community. He was worried at first about what people would think of him, but found that calling on God to help him with this helped him face his fears and feel more hopeful. He then started reading four of the five daily prayers required by Islamic teachings; towards the end of therapy he achieved his last goal of praying the morning prayer as his sleep had improved and he felt he could wake up for this prayer too. Achieving what he had previously managed to do and had valued, made him feel less guilty and stopped him thinking of himself as a ‘bad Muslim’ for not praying.

The client’s depression scores at the end of therapy were not in caseness; he had improved in most areas of his life and felt he could maintain these changes and add to them. He also began seeking legal advice to start court proceedings in the hope of gaining access to his children.

Case study 3

This client was a single mother with two children going through a divorce at the time she began therapy. She had stopped praying, both the obligatory prayers and also personal supplications to God, that she used to do, and was no longer reading the Quran every week. Beyond doing necessary tasks, she had not been spending time doing enjoyable activities with her children. The client said she thought of herself as a bad Muslim because her marriage had not worked out and as a bad mother for not enjoying time with her children and having to go to work. She felt anxious, tired and busy all the time and had been binge eating at night as a coping method.

A values assessment helped to map out those values that she felt were not being met, linked to activities that she had stopped. Through weekly goals she scheduled alternative coping behaviour, including reading the Quran as a form of relaxation and using the self-help booklet for religious motivation. She found it useful to reframe her difficulties as tests and found comfort in acknowledging that Allah is Merciful and Forgiving towards those who are going through a hard time and He rewards patience. This helped her to realize that she was being very hard on herself.

Working with the therapist to challenge negative thoughts helped her recognize that she was spending time ruminating, making her low mood worse and causing her to turn to binge eating. She planned to focus her attention by using mindful colouring activities at night and having a bath. To re-establish her routine of praying, she found it easier to start with the morning and evening prayers, on the days that she was working. By resuming this routine she began to feel better in her mood and after some weeks she was able to start reading the obligatory daytime prayers at work too. She planned enjoyable activities to do with her children every week, starting with activities at home, as this felt easier. After a few weeks the client felt able to plan an activity outside of the house, such as going for a walk with her children or taking them to the park. She re-established her personal supplications to God in which she asked for help with her divorce and with her chores. In doing so, she felt better about herself for having this connection in which she would speak to God. This made her feel stronger and able to face issues she had been avoiding such as dealing with her divorce papers.

Towards the end of therapy she felt energized, better in mood, and was spending less time ruminating about the past. She was no longer avoiding the things she needed to do. She continued to schedule activities and began to learn the 99 Names of God. This gave her a sense of achievement, as something she would be rewarded for in the hereafter.

Case study 4: client group

Touchstone’s links with Leeds Grand Mosque led to outreach events being held at the mosque to let people know about the availability of Adapted-BA and to encourage self-referral from this under-represented population. Self-referral is the most common route to services offered by Touchstone and referrals are also accepted from other mental healthcare providers, such as GPs.

Initial attempts to encourage self-referral following these events were not as successful as anticipated and it became clear that more groundwork was needed. In collaboration with the mosque, a group-based BA course was established and delivered in the mosque venue. This drew on elements of the self-help booklet and made the resource available to group participants who wished to use it. Mosque committee members were involved in publicizing the group therapy and this helped to establish trust in the initiative. Both groups were advertised for men and women, although no referrals were received from men the first time. In the second group, only two were received for men, which was not enough to run another group as most participants preferred single gender groups. Male referrals were therefore offered the option to receive the same content as the group but on a 1:1 basis.

All attendees were over 18 years of age. More than half had accessed some form of therapy in the past, although not necessarily with IAPT. Some referrals had no previous history of accessing services but described experiences of low mood over the years. The general consensus amongst participants was that the faith-based element was useful on its own and had motivated those who were referred to or attended the group to access support.

Case study 5: mosque group participant

A female participant in the 6-week mosque-based course had converted to Islam before marrying her Pakistani husband. She was seen as an ‘outsider’ and experienced hostility from his family, especially her elderly mother-in-law. This involved criticism and personal comments attacking her identity and self-esteem as a Muslim woman, wife and mother. The client felt guilty and that she was sinning after being accused of disobeying and disrespecting an elder and that she was destined to be punished in this life and the hereafter. She felt Allah was not happy with her and her efforts and that she was not good enough.

Other group participants normalized her experience, highlighting that being a convert could often involve unfair treatment from in-laws. They also identified supportive Islamic teachings enabling the client to see her experience as a ‘test’ and compare this with relevant incidents from the life of the Prophet Muhammad. Furthermore, the client began to appreciate the value of being patient and focusing on Allah’s forgiving and merciful nature. A further suggestion from other participants aimed at supporting her recovery from depression involved speaking to the mosque Imam about her situation in order to challenge myths about Islam and build up her knowledge of Islamic teachings.

The client made a full recovery from her depression symptoms by the end of the course. As the group ended nearly a year ago, this cohort still meets up at the same time that the course used to run in the mosque and have become a community of support for each other. Group members bring their self-help manual, encouraging continued goals that match their values and faith.

The group sessions have been completed twice within the mosque setting and this has further supported and built trust with local Muslim communities with promising results (see Table 1).

Table 1. Uptake and recovery results for Group Adapted-BA therapy

Whilst these results relate to relatively small numbers of clients, they constitute large increases in the number of Muslim referrals/self-referrals to the service and considerable improvements from the national figures for six sites highlighted in Table 2. Half of those recruited to the course and 66% of those completing the 6-week programme reported recovery from depression as measured by the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 questionnaires. In contrast, national IAPT data indicate that Muslims in the six sites we explored had rates of reliable recovery ranging from 0 to 17%.

Table 2. Analysis of national IAPT data for six sites

A further evening course is planned to take place in the mosque in the near future. This collaboration illustrates how accepted attitudes and ways of working are unsettled during service improvements, particularly for under-served groups (Dowrick et al., Reference Dowrick, Chew-Graham, Lovell, Lamb, Aseem and Beatty2013). Partnership working has been essential to resolving access barriers in order to achieve implementation of this successful service innovation (Greenhalgh et al., Reference Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate and Kyriakidou2004).

Conclusion and limitations

Initial implementation findings for this socially inclusive approach to health care for Muslim populations suggest that it is likely to increase access to depression therapy and offer support that meets cultural needs within this population. The existing evidence base for BA indicates that this improved access to therapy will improve treatment outcomes and reduce the longer term nature of depression experienced within Muslim populations (Sproston and Nazroo, Reference Sproston and Nazroo2002). A limitation of the current evidence about delivery of Adapted-BA in practice is that it has been adopted by a relatively small number of IAPT services – apart from Touchstone, IAPT teams at Redbridge, Kirklees, Leeds NHS and Oxford IAPT have received the training. However, the approach has not been promoted at a national level, despite Touchstone representations to senior managers of IAPT about its value and appeal to Muslim service users.

For service users, the adapted therapy models a socially inclusive approach and facilitates the input of community organizations into service development, enhancing the resources available to therapists working with Muslim clients. There is potential for other social groups experiencing disadvantage in terms of access and outcomes to also benefit from the model developed.

For therapy practitioners, commissioners and trusts the approach supports improved awareness, capacity, performance and decision-making in relation to delivering services that meet the needs of local populations, in line with NICE and Department of Health guidance. Learning and consequent changes in practice are likely to improve capacity and leadership in the areas of cultural competence and implementing novel interventions.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor Robert West at the University of Leeds for his analysis of IAPT figures at six sites across England. We also thank the Yorkshire and Humber Research for Patient Benefit Board, which funded the study to develop and pilot Adapted-BA for Muslim service users.

Financial support

This paper presents work based on independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme (grant reference number PB-PG-1208-18107). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for the research on which Adapted-BA is based was granted by the Yorkshire and Humber Research Ethics Committee.

Key practice points

(1) There is evidence of professional uncertainty among practitioners about how to engage with ethnic and religious diversity and concerns about inequitable provision among commissioners. National IAPT data highlight under-referral of Muslim communities to therapy services and considerably poorer recovery rates for Muslims compared with the general population. Analysis elsewhere has shown similar patterns for BME groups nationally, indicating that cultural adaptations for other minority ethnic and religious groups are also needed.

(2) Muslim clients are more likely to use religious coping techniques than individuals from other religious groups in the UK. There is evidence that interventions drawing on faith can be effective in addressing and preventing depression and improving quality of life. A culturally adapted therapy based on behavioural activation, an existing evidence-based treatment, has been developed and piloted by a multi-disciplinary team and incorporates evidence-based approaches to engaging with Muslim clients with depression. The adaptation supports therapists to engage positively and reflexively with a group that routinely experiences high levels of negative social and media misrepresentation and widespread racism. Apart from engagement with religious identity, issues such as stigma, collective family structures and supernatural explanations for depression are also covered within a therapist manual and best practice approaches that therapists can adopt are identified. A self-help booklet that brings together Islamic teachings that support and reinforce therapeutic goals has also been developed.

(3) The intervention is currently being delivered by Touchstone, an IAPT service in Leeds, and this has improved access to the service as well as treatment outcomes for Muslim service users. The approach helps therapists to be more self-aware of their assumptions, about religion in general and Islam or Muslims in particular, and encourages a patient-centred approach that actively recognizes the social stigma that Muslims often face in the UK and globally. For Muslim clients, a space is created in which they can say that religion is important to them or to omit religion from their identified values. Clients choosing the adapted approach are supported to draw on Islamic teachings that reinforce the therapeutic goals of BA from within a familiar and valued framework. Broader cultural issues beyond religion such as stigma, family dynamics and supernatural understandings of depression can also be discussed in Adapted-BA and religious teachings can be a powerful tool to empower clients in relation to such issues. The approach unsettles accepted attitudes and ways of working, which is an essential process in service improvements for underserved groups. Partnership working with families and community organizations has been essential to achieving implementation of this successful service innovation.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.