Being both an improviser and an academic music theorist often prompts me to reflect on the relationship between theory and practice. Creative artists often hear or offer warnings about the rigidity of theory and its impediment to creativity; jazz musicians’ preference for pragmatism often contrasts with theory's more abstract facets.Footnote 1 Improviser Derek Bailey states that a “theory of improvisation” is a contradiction in terms, opposing theory and practice in his sprawling exploration of improvisation across musical genres.Footnote 2 Generally, being told that your music “sounds theoretical” is a critique that suggests a lack of “artistic” or “human” elements. Theory in such estimations at best is unnecessary or at worst threatens to undermine the creative process itself.

This opposition hinges on a rather rigid view of music theory. The field of music theory admittedly does not often advertise its utility for creative practice. Nonetheless, in my experience as both a practitioner and a researcher of jazz and improvised music, creative artists often use music theory as a source of new musical ideas. This is not to say that these creative musicians necessarily improvise with strict adherence to a Schenkerian Urline, hexachordal combinatorial sets, or other theoretical constructs, but rather that they often adapt music theory to their needs and interests. This article explores that connection.

A striking instance of music theory's role in creative, experimental music—and the focus of this article—is Muhal Richard Abrams's engagement with Joseph Schillinger's The Schillinger System of Musical Composition (hereafter, SSMC).Footnote 3 Abrams (1930–2017) was one of the founding members of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), a hugely influential collective of Black experimental composer/musicians formed in 1965 on the south side of Chicago that still operates today, its first president, and an important mentor to many young musicians both during the organization's early stages and beyond.Footnote 4 He was a recognized master pianist, composer, and improviser who was based in Chicago from 1930 to 1976 and New York City from 1976 until 2017, designated as a “jazz master” by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) in 2010, inducted into DownBeat magazine's Hall of Fame in the same year, received an honorary doctorate in music from Columbia University in 2012, and commended as an honorary member by the Society for American Music in 2006. He created a compelling and diverse discography, performed on the world's largest stages, and advised and mentored generations of younger musicians. An iconoclast, Abrams continually developed his creative approach by absorbing and adapting varied ideas from the fields of visual arts, science, philosophy, metaphysics, and, of course, music.

Schillinger (1895–1943) is mentioned in many discussions of Abrams and his work, albeit usually in a cursory fashion. Abrams cites Schillinger in connection with The Experimental Band, a primary precursor to the AACM, in a 2009 interview with Don Ball for the NEA:

The Experimental Band, I put that together because I had encountered a series of study methods: the Schillinger method … was one. I had compiled a lot of information from studying the Schillinger system and other areas of study also. I had amassed all of this information about composing and it wasn't necessarily a mainstream approach, so I needed some apparatus in order to write this music and express it. So as a result, I organized the Experimental Band for that purpose, and also to attract other composers so they could develop their skills in writing for the group ensemble also.Footnote 5

Schillinger's name also appears in public, musicological, and personal discourses regarding Abrams. Obituaries for Abrams in both The Guardian and New York Times mention him, and Greg Thomas referenced Schillinger's texts as a testament to Abrams's determined and robust auto-didacticism during a talk at the National Jazz Museum in Harlem on February 6, 2018.Footnote 6

Abrams used Schillinger's theoretical writings in both his compositional and pedagogical practice—Amina Claudine Myers, John Stubblefield, and George Lewis, among others, recall Abrams teaching them Schillinger's methods during the first decades of the AACM.Footnote 7 Finally, pianist and former Abrams student Jason Moran remembers attending Abrams's Schillinger-based composition classes at Greenwich Music House in Greenwich Village, New York as late as 1998, demonstrating that Abrams's use of SSMC extended beyond his tenure in Chicago.Footnote 8

SSMC is not, however, a singular fountainhead for Abrams's practice: “I am the sum product of the study of a lot of things,” he notes.Footnote 9 Thus rather than suggest that Abrams literally adopted Schillinger's musical system, I examine Abrams's adaption of it into his creative practice. Crucial here is that Abrams took up some aspects of SSMC and ignored others, combining them with many other ideas.

Abrams's ardent eclecticism subsists within what Lewis famously calls an “Afrological” belief system, which prioritizes a musician's “‘sound,’ sensibility, personality, and intelligence.”Footnote 10 The Afrological's emphasis on personal creativity helps explain why some components of Schillinger's theory were useful to Abrams while others were not; that is, he took theoretical ideas that invigorated and expanded his “sound,” bending them to his creative needs. This ambivalence encapsulates an important theme in this article: the creative model epitomized by Abrams and the AACM customizes music theory toward personal creative ends.

Abrams's adaption of SSMC also connects to various modes of syncretism in the Black musical tradition. Samuel A. Floyd Jr. discusses how Black musicians combined hymn tunes and spirituals, unique harmonies, polyrhythms, and elements of Black dance with musical forms derived from waltzes, mazurkas, and other European idioms.Footnote 11 Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr. similarly notes Afro-modernists’ synthesis of “art,” “popular,” and “folk” elements while in dialogue with Euro- and United States-centric forms of modernism, all as part of larger efforts to counter anti-Black stereotypes perpetuated by white audiences, critics, and producers.Footnote 12

These kinds of appropriations are also Afro-diasporic in scale, creating global resonances for Abrams's creative practice. Work by Frantz Fanon, Édouard Glissant, Jean Bernabé, Patrick Chamoiseau, and Raphaël Confiant suggests that “creolized” culture expresses a kind of freedom drive in response to colonial subjugation, cultural imposition, and obscured originary communities by synthesizing ideas from many different sources.Footnote 13 Connecting Abrams to this cultural network situates his creative practice in both North American and global traditions of syncretism.

This notion of adaption and synthesis should not be confused for narratives of cosmopolitanism and assimilation, a point which informs how I formulate musical analysis in this article. Glissant, Fabien Jean-Georges Granjon, George Lewis, Christina Sharpe, and Deborah Wong all warn against narratives of assimilation, inclusion, and aesthetic unity in analyses of syncretism.Footnote 14 For this article, this injunction means regarding Abrams's uses of Schillinger's ideas not as simple instances of cut-and-paste—where analysis simply identifies clear correspondences between source material and its application—nor as merely ornamental in relation to an otherwise homogenous musical palette. Instead, my analyses show how traces and fragments of Schillinger's theory appear as part of Abrams's complex musical textures.

Abrams's adaption of SSMC—and other, similar Afrological appropriations of music theory—generates new understandings of what theory offers the creative artist. First, theory helps generate novel musical material on a local level. Abrams ignores, for example, Schillinger's broader mandate for hierarchical structural relationships.Footnote 15 Instead, he focuses on concepts that generate musical materials for the musical surface. The abstract nature of SSMC practically encourages appropriation in the name of creativity and innovation: almost every page of the two volumes displays musical examples that creative musicians could adapt for their own ends. In this framing, theory's abstraction serves individual agency and creativity, offering a space for speculation and invention in service of musical practice.

Second, these adaptions extend and amplify embodied performance. The novel musical material that emerges from such music theoretical engagements challenges instrumental technique, aural skill, and improvisational dexterity. Overcoming these challenges leads to musical development. Jason Moran describes Schillinger's utility in such terms: “[It] helped me break the mold of sitting at a piano and thinking what sounds pleasing to my ear, and instead be able to compose away from the instrument—to almost create a different version of yourself.”Footnote 16 Moran notes that Schillinger's techniques bypass pre-learnt physical and aural scripts. The resulting material extends instrumental/vocal technique and aural skills. This process of what I call “purposive disembodiment”—creating new musical challenges by temporarily disregarding embodied aspects of performance—ensures that these music theoretical engagements are not simply academic. Rather, they participate in broader practices of music making, creative expression, and personal development.Footnote 17

Finally, these adaptions of music theory reflect an expansive worldview that critiques narrow ideas about Black creative practice. As I discuss below, Schillinger's work helped Abrams create new compositions that contrast markedly with his previous work in straight-ahead jazz. Abrams used Schillinger's ideas as part of his efforts to develop an experimental practice that overflows and critiques narrow genre categorization.Footnote 18 The creative adaptions that I highlight in this work similarly suggest that music theory can help musicians sidestep idiomatic conventions, pushing them into more experimental realms.

This article avoids casting Schillinger's text as a straightforward rubric for analyzing Abrams's music, even as it suggests that some of Schillinger's ideas can be found in his works. My analyses of Abrams's compositions “Inner Lights,” “Positrain,” and “Roots” uncover traces of Schillinger's theory while also showing ways that Abrams diverged from it.Footnote 19 These analyses follow my account of Abrams's “discovery” of Schillinger's book, which furnishes historical context for both Schillinger and Abrams. Following my analyses, I briefly explore additional resonances between Schillinger's text and Abrams's creative philosophy to suggest why Schillinger's books appealed so strongly to him. Ultimately this article aims to both elucidate Abrams's encounter with Schillinger's work and suggest that it signifies a broader network of music theory linked to African American creative practice. I explore these resonances further in my conclusion.

Schillinger and Abrams's “Discovery”

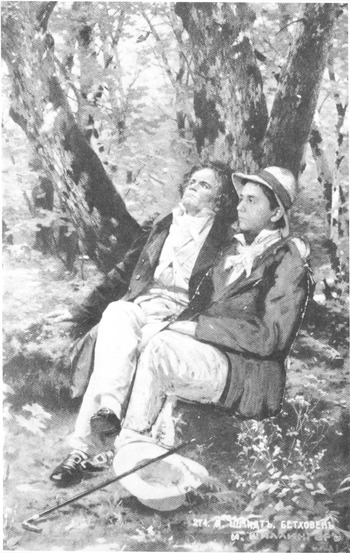

Born on September 1, 1895 in modern-day Kharkov, Ukraine, Schillinger was a lauded composer in Russia and friends with Dmitri Shostakovich, who viewed him as a successor to the great European composers such as Beethoven and Tchaikovsky. Shostakovich even created a picture depicting a young Schillinger pondering nature, arm in arm with Beethoven (Figure 1).Footnote 20 Schillinger also loved American music: he organized and lectured at Russia's first so-called jazz concert on April 28, 1927, which included performances of pieces by American composers such as George Gershwin and Irving Berlin. In the following year Schillinger was invited to visit the United States by a committee that included John Dewey, Leopold Stokowski, and Edgard Varèse (among others) “for the purpose of giving lectures and concerts devoted to the young Russian school of composers which is yet unknown in America.”Footnote 21

Figure 1. Dmitri Shostakovich's depiction of Beethoven and Schillinger. Drawing of Beethoven and Schillinger; unknown date; Joseph Schillinger papers; Box 1; Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Library (reproduced in F. Schillinger 1976, 116). Joseph Schillinger System of Musical Composition, Courtesy of Carl Fischer, LLC. All rights reserved. Used with Permission.

In New York, Schillinger shifted his focus to presenting and teaching his theories of music and art. In 1931 he gave a series of twelve weekly lectures titled “Rudimentary Analysis of Musical Phenomena” at the Theremin Studio on West 54th Street, and at the end of 1932 he offered a 12-week course, “New Art Forms: A Speculative Theory of Art” at the New School for Social Research. He continued presenting his work in similar forums, presenting “General Theory of Rhythm as Applied to Music” in December 1936 at the annual meeting of the American Musicological Society (AMS), which he also helped cofound.Footnote 22 The Schillinger System of Musical Composition (SSMC) and The Mathematical Basis of the Arts—Schillinger's magnum opera—were published posthumously in 1946 and 1948, respectively. They offer definitive representations of his compositional method, teaching materials, and aesthetic.Footnote 23 His Encyclopedia of Rhythms appeared later, in 1976, and tabulates many of the rhythmic patterns outlined in SSMC.Footnote 24 Once in print form, Schillinger's work was disseminated across the country, eventually finding its way to Chicago.

Chicagoan pianist, arranger, and producer Charles Stepney (1931–1976) first introduced Abrams to Schillinger's work in 1957. Stepney studied theory treatises in order to augment his already considerable creative palette, and applied these methods to his work as a producer with The Rotary Connection, Minnie Riperton, Earth Wind and Fire, and the Dells among others.Footnote 25 Stepney met Abrams through Walter “King” Fleming (1922–2014), who was one of Abrams's early musical mentors and recorded for (and with) Stepney for Chess Records.Footnote 26 Abrams carried Schillinger's massive tomes “everywhere he went over the next four years.”Footnote 27

That period with Schillinger's theory treatise, 1957–1961, represents the beginning of an evolution in Abrams's creative practice. His first commercially available recording, Daddy-O Presents MJT + 3 from 1957, presents him as a consummate post-bop jazz pianist and composer. Although this recording places Abrams firmly in Chicago's “modern” jazz scene, it hardly exhibits the experimentalism that marks his subsequent recordings. In 1961 Abrams founded an outlet for his new Schillinger-influenced compositions—The Experimental Band—which helped him develop and solidify his experimental creative practice.Footnote 28

The Experimental Band functioned as an outlet for a community of musicians’ experiments in composition and improvisation, including Abrams's new, Schillinger-influenced palette. It grew out of a group that was formed by mainstream players to read through charts and rehearsed at the C&C Lounge on Chicago's south side, representing a much-needed collaborative forum for its members to develop compositional and improvisational skills outside of both the school system and sometimes unwelcoming jam sessions in Chicago.Footnote 29 This band serves as an important precursor to the AACM, helping many of its members to meet and collaborate for the first time.Footnote 30

SSMC provided Abrams with new ideas on creativity and experimentation that advanced his mission of finding and developing his personal creative practice: “I was really educated now, in a big way, because I was impressed with a method for analyzing just about anything I see, by approaching it from its basic premise. The Schillinger stuff taught me to break things back down into raw material—where it came from—and then, on to the whole idea of a personal or individual approach to composition.”Footnote 31 SSMC provided Abrams with a method of both analyzing existing compositions and, crucially, generating musical material that did not directly derive from the jazz idiom.Footnote 32 It marks an important musical development in Abrams's trajectory, one that orients his creative output toward the experimental aesthetic that is demonstrated by his many wonderful performances and recordings.

Putting Theory into Practice

In this section I gloss Schillinger's methods of permutation, interference, and pitch symmetry to analyze excerpts from Abrams's “Inner Lights,” “Positrain,” and “Roots,” respectively. I highlight some of the ways that Abrams transforms Schillinger's methods even as they leave their indelible mark. These analyses demonstrate that SSMC provided Abrams with novel ideas for musical composition even as he maintained ultimate creative agency.

Permutation and “Inner Lights”

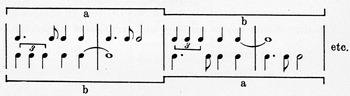

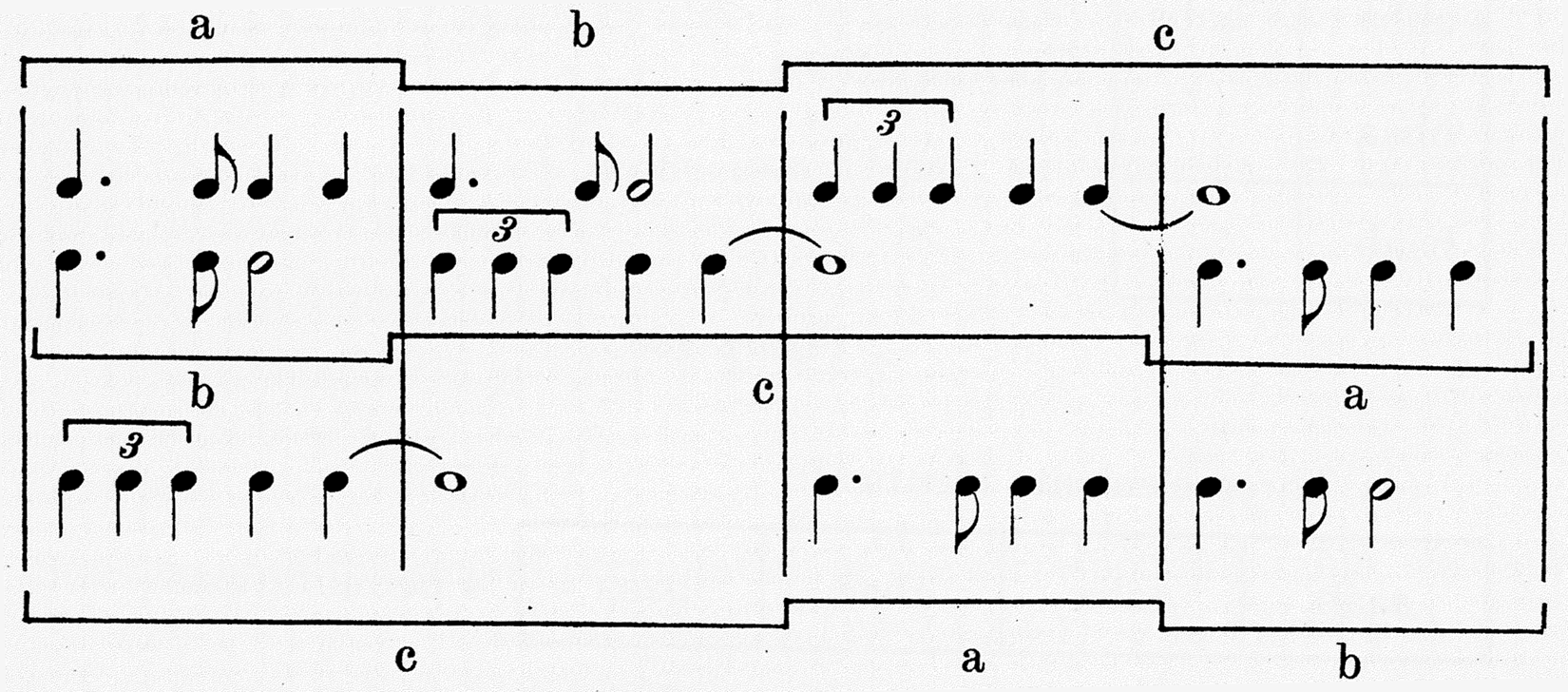

Permutation is an extremely important organizational and generative principle in SSMC. Any musical segment may be divided into elements of any size, equal or unequal, and then systematically reordered to create complementary material. The most striking example of permutation in SSMC is Schillinger's multiple polyphonic settings of the Arthur Johnson and Johnny Burke's song “Pennies from Heaven.” Schillinger first uses the song to demonstrate his method of generating a countermelody by reordering segments of the primary melody. His illustration, shown in Example 1, segments the rhythm of the melody in the mm. 1–4 of “Pennies” into two halves and reverses their order to generate a counter melody—mm. 3 and 4 of the original melody (shown in the upper part) became the accompaniment (shown in the lower part) for mm. 1 and 2 and vice versa.Footnote 33

Example 1. Schillinger's two-part rhythmic segmentation and permutation of “Pennies from Heaven” (his Figure 88, [1946] 1978, 50). Joseph Schillinger System of Musical Composition, Courtesy of Carl Fischer, LLC. All rights reserved. Used with Permission.

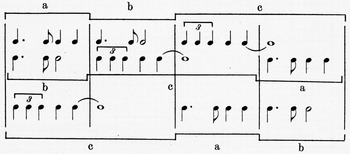

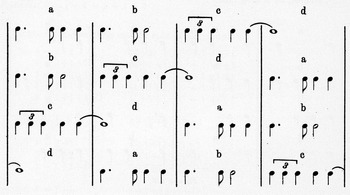

Segments may be of any length and need not be equal, and Schillinger returns to “Pennies” to demonstrate: he divides the melody into three parts of unequal length to generate two countermelodies against the original a few pages later (Example 2), and again into four equal parts to generate three countermelodies for a total of four parts (Example 3).Footnote 34

Example 2. Schillinger's three-part rhythmic segmentation and permutation of “Pennies from Heaven” (his Figure 105, [1946] 1978, 55). Joseph Schillinger System of Musical Composition, Courtesy of Carl Fischer, LLC. All rights reserved. Used with Permission.

Example 3. Schillinger's four-part rhythmic segmentation and permutation of “Pennies from Heaven” (his Figure 118, [1946] 1978, 62). Joseph Schillinger System of Musical Composition, Courtesy of Carl Fischer, LLC. All rights reserved. Used with Permission.

Permutation at the level of individual pitches also appears in SSMC and Gershwin's “The Man I Love” serves as Schillinger's example.Footnote 35 In Example 4 Schillinger individuates the pitches in each phrase and rearranges them to create motivic variation.Footnote 36

Example 4. (a–b) Schillinger's motivic variations on mm. 1–4 of Gershwin's “The Man I Love”: (a) original and (b) variations (his Figures 8 and 9, [1946] 1978, 111). Joseph Schillinger System of Musical Composition, Courtesy of Carl Fischer, LLC. All rights reserved. Used with Permission.

Abrams's “Inner Lights” reflects Schillinger's principles of permutation when applied to a polyphonic texture. This compact composition appears as the final track on View From Within (1985), and alternates between written material and “free” improvisation: 12-measure A- and B-sections give way to an improvised bass solo (section C), followed by a 5-measure D-section that is played twice, an improvised piano solo (section E), a 3-measure F-section that is played four times, and finally an improvised flugelhorn solo. The instrumentation for this section is alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, flugel horn, vibraphone, double bass, drums, and piano.

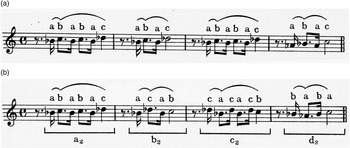

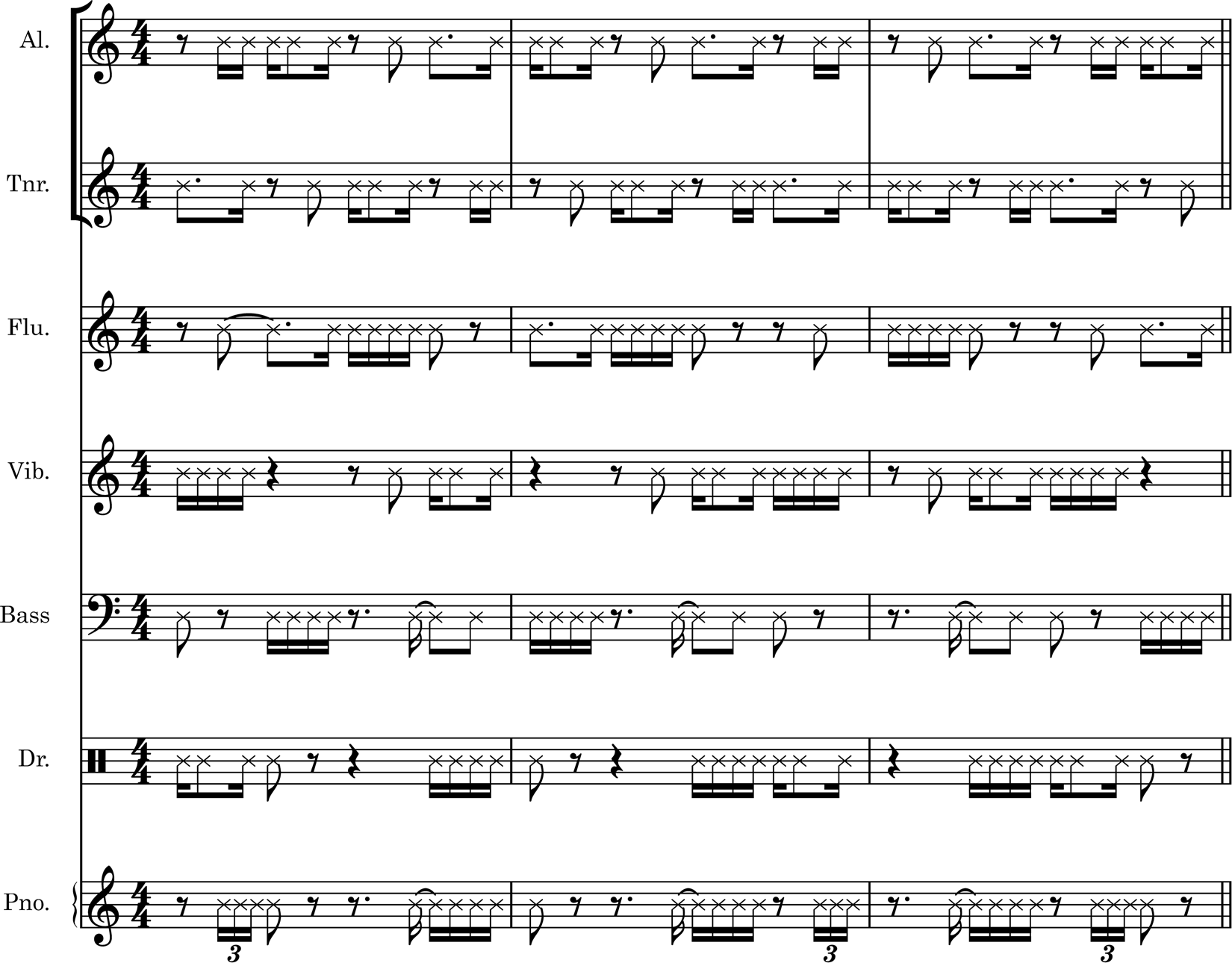

My rhythmic transcription of this section appears in Example 5. Each beat constitutes a group in my analysis. Examining individual parts first, m. 2 in every part rotates the groups of m. 1 “to the left” and m. 3 applies the same transformation to m. 2. Put differently, the rhythms of beats 1, 2, 3, and 4 in m. 1 appear on beats 4, 1, 2, and 3 in m. 2, respectively, and the same process applies for m. 3 in relation to m. 2.Footnote 37 These relationships are summarized in Example 6.

Example 5. Rhythmic reduction of the final notated section of “Inner Lights.” Rhythmic reduction by author. Muhal Richard Abrams, “Inner Lights,” score, c1984, Ric-Peg Publishing, Ablah Library, Wichita State University.

Example 6. Permutation of one-beat groups in “Inner Lights.”

Permutation also occurs between parts. The first measure of the tenor saxophone part reverses the order of the one-beat groups in the first measure of the alto part. The same relationship holds for the double bass in relation to the flute. The drum and vibraphone parts have a slightly different relationship, they are the reverse of one another; that is, the drum part is the vibraphone part read from right to left. The piano part is not a transformation of any other part, which means that Abrams's primary instrument represents divergence from Schillinger's theory in this texture. Table 1 summarizes these relationships. Each box represents one beat. Reading the letters horizontally in each part emphasizes the rotation of rhythms in individual parts, and matching letters between parts show retrogressive relationships. “R” in the drum part indicates that each beat of the vibraphone part appears in reverse.

Table 1. Combined horizontal and vertical transformations of Example 6

Interference and “Positrain”

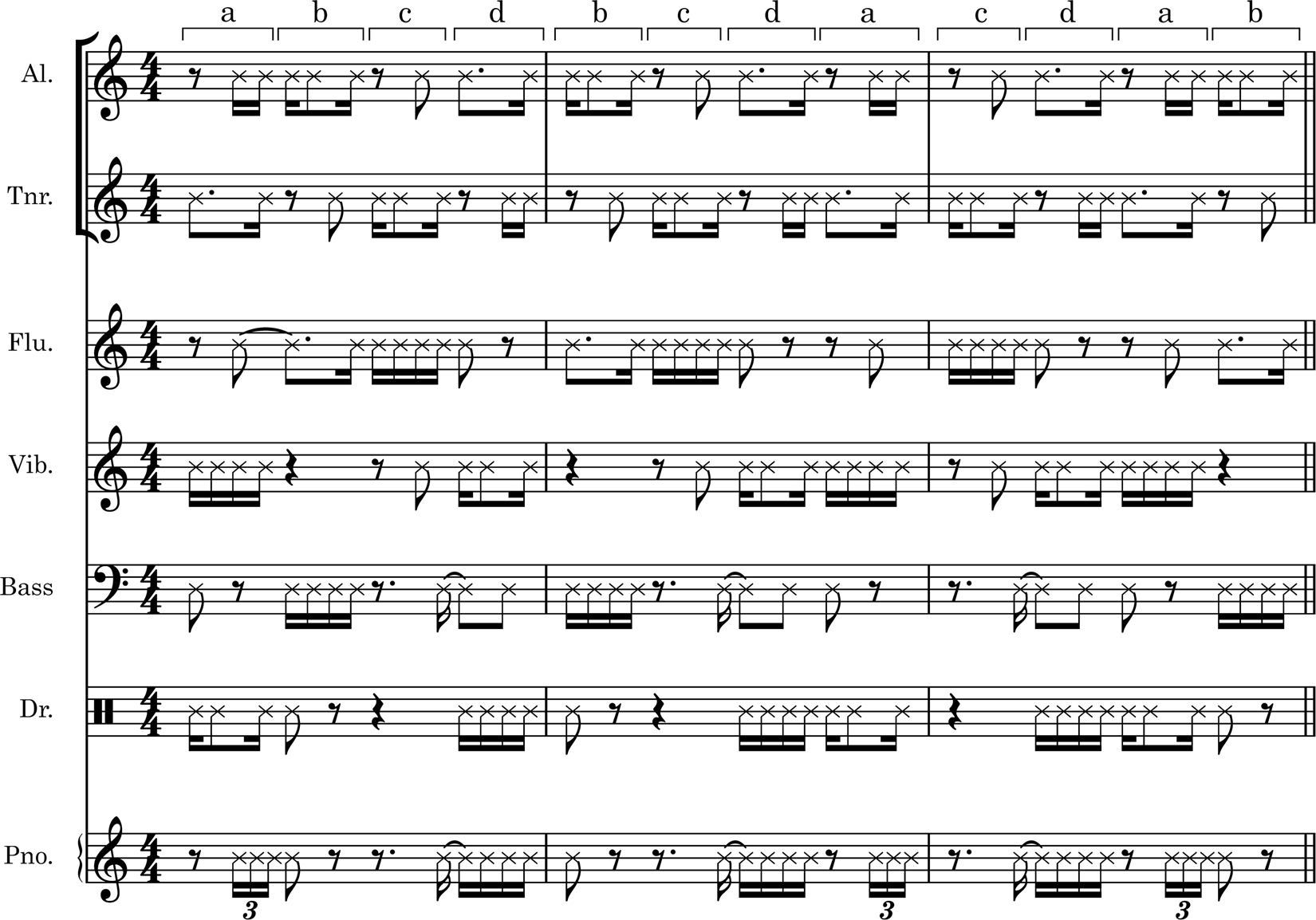

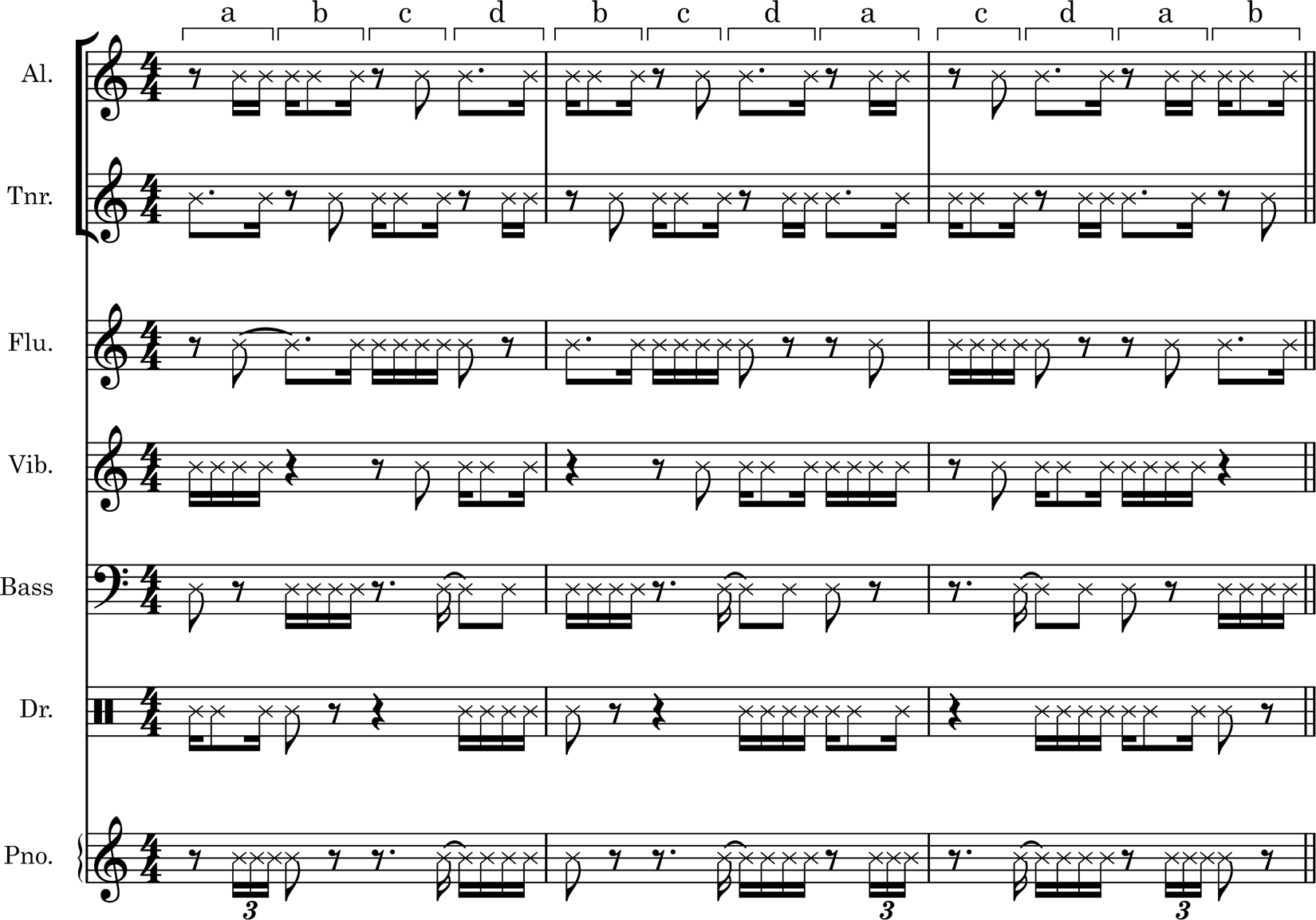

Schillinger's notion of “interference” theorizes the melding of rhythmic and melodic patterns (what he calls “Coordination of Time Structures”).Footnote 38 Central to interference is the number of attacks in a rhythm and the number of pitches in a set. A rhythm with four attacks, for example, “interferes” with a set of five pitches to generate a figure with a total of twenty attacks that contains five iterations of the rhythmic pattern and four iterations of the pitch set before repeating. Schillinger represents this process of interference between the pitch and rhythmic domains using ratios. The first line of Schillinger's example (shown in Example 7) states that the pitch set contains five attacks (“aa = 5a”) and the rhythmic figure contains four attacks (“aT = 4a”) over six eighth notes (“T = … 6t”).Footnote 39 The next lines show the interference between pitch and rhythm: the complete phrase contains twenty attacks, five iterations of the rhythmic figure (quarter-note, eighth-note, eighth-note, quarter-note), four iterations of the pitch set (D, Eb, D, F#, G), and lasts for the equivalent of thirty eighth notes.

Example 7. Schillinger's coordination of “time structures” (his Figure 859, [1946] 1978, 37). Joseph Schillinger System of Musical Composition, Courtesy of Carl Fischer, LLC. All rights reserved. Used with Permission.

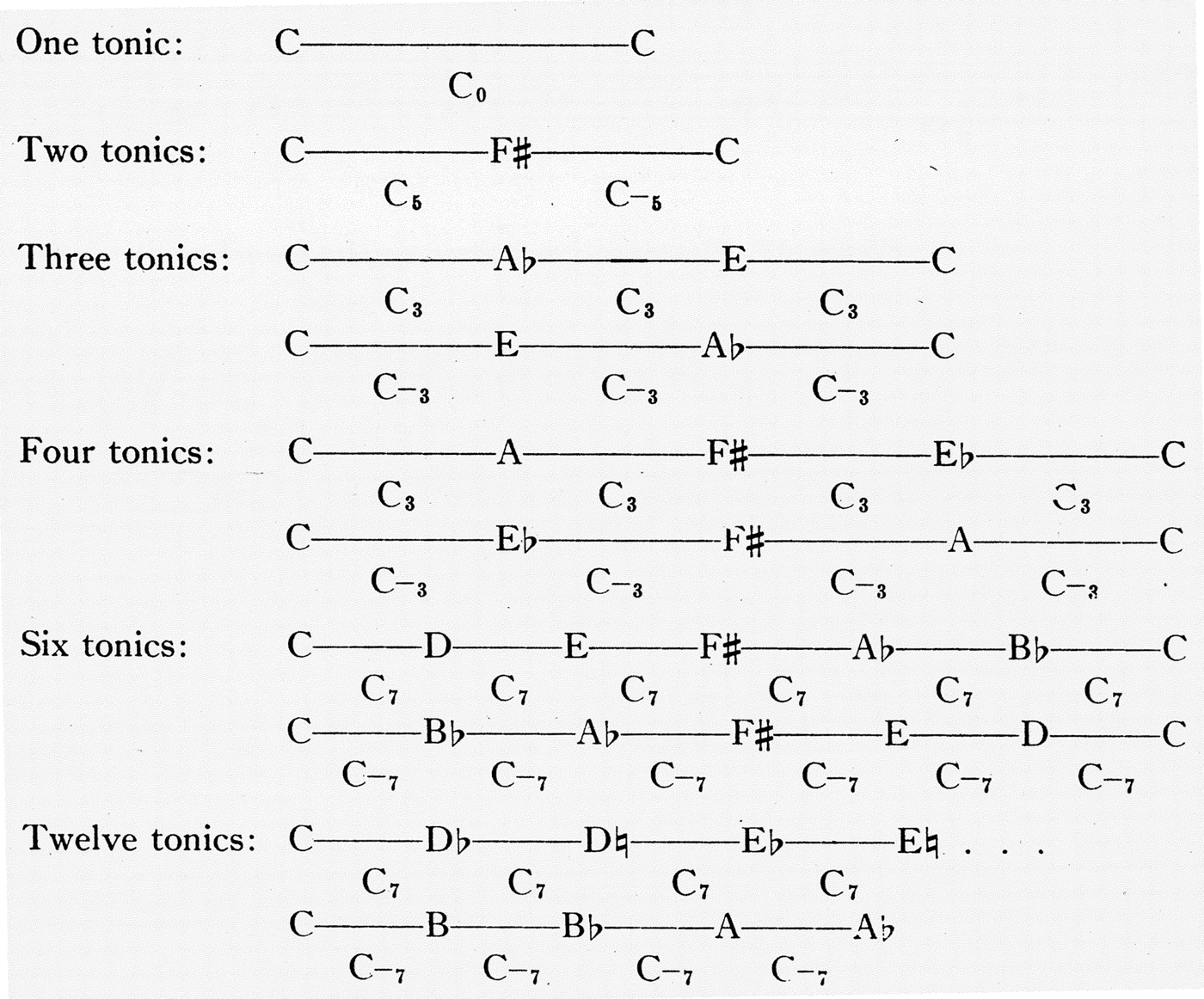

Abrams employs this device in “Positrain,” also from View from Within. The double bass part 4 measures before rehearsal number 6 features the ostinato shown in Example 8. This part emerges from the “interference” of a cycle of three pitches—E, F#, B—and a rhythmic pattern that features two attacks, realized as the equivalent of an eighth note followed by a quarter note (1 + 2), shown in Examples 9 and 10. Abrams's ostinato repeats this rhythmic pattern while cycling through these three pitches. The polyrhythmic relationship between the pitch and rhythm cycles creates a disorienting effect for the listener.

Example 8. Abrams's double bass part in “Positrain,” four measures before rehearsal number 6. Muhal Richard Abrams, “Positrain,” score, c1984, Ric-Peg Publishing, Ablah Library, Wichita State University.

Example 9. Pitch cycle for Example 8.

Example 10. Rhythm/attack cycle for Example 8.

Abrams only departs from this pattern by including an attack on the very first downbeat, creating an initial three-attack group with durations of 1 + 1 + 1. This variation is indicated in Example 10 with a bracketed note head. The complete resulting “interference” pattern lasts nine eighth notes, obscuring the notated 12/8 meter and adding an additional layer of rhythmic opacity.

Abrams's three melodic parts that coincide with this bass ostinato—for two bass clarinets and trumpet—operate independently from Schillinger's theory. They thus testify to the way Abrams incorporated it into his broader creative practice. The upper bass clarinet part utilizes constant dotted quarter notes: Ab5, F5, E5, A4, Ab4, Bb4, F5, Gb5, D5, C5, Db5, Eb5, E5, B4, A4, G#4. I hear this passage as a chromatically embellished E Lydian collection; F, A, D, and C all function as neighbor tones. Movements such as A4–Ab4 near the beginning of this passage are conventional neighbor tone motions, but others, such as Bb4, F5, Gb5, D5, C5, Db5, are more complex. This example leaps upward from the Lydian scale's (raised) fourth degree (enharmonically A#) to the second scale degree (enharmonically F#) with its lower neighbor before utilizing a double neighbor to the sixth scale degree (enharmonically C#). Overall, this melody is anchored to the E in Abrams's ostinato while adding chromatic hues.

The other two melodic parts for these four measures obscure any sense of central tonality. The second bass clarinet part hockets with first clarinet's dotted quarter notes, playing one or both of the intermediate eighth notes. It also nimbly hops between segments of various diatonic collections, Db, C, Bb, G, Ab, F (part of the Ab major scale), F#, E, G, A (part of the G and D major scales), Bb, A, F, Eb (part of the Bb major scale), for example, without prioritizing any one in particular. This tonal ambivalence counters the emphasis on E in both the ostinato and first clarinet part. The trumpet part is more rhythmically and harmonically varied than the others and constitutes the primary melody. At times it suggests affinity with the first bass clarinet by loosely mimicking its melodic shape, while at others it obtusely hints at snippets of contrasting diatonic collections. Suffice to say that this melody, striking as it is, neither reinforces Abrams's ostinato nor embodies any of Schillinger's other methods for generating melodies.

The result of Abrams's layering is a singular kind of musical texture. The triplet feel dominates this section. Both the hocketing upper parts and ostinato obscure the four-beat cycle of the 12/8 meter, however. Harmonically, this section sits in a beautifully liminal space between tonality, polytonality, and atonality. Both Abrams's ostinato and the first clarinet part propose E as primary pitch for the section, but the second clarinet and trumpet parts mitigate hearing it unequivocally as the tonic.

My primary point here is that Abrams deploys Schillinger's interference technique for his bassline but also obscures this adaption by overlaying three melodic parts that operate otherwise. These parts may have been composed using some other theoretical system or combination of systems, by playing the piano or another instrument, or audiated. Whatever the genesis of these parts, these four measures express Abrams's incorporation of Schillinger's theory within his larger creative practice.

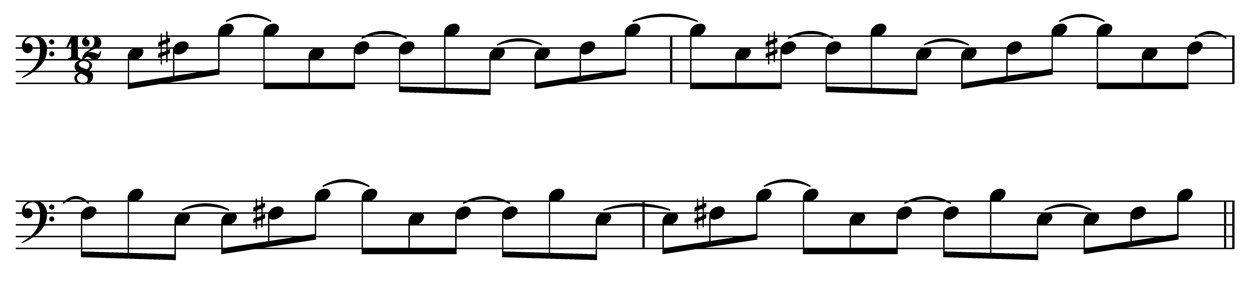

Pitch Symmetry in “Roots”

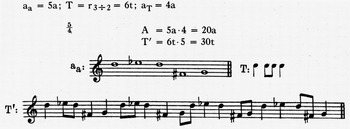

Chapter 5 of Schillinger's “Special Theory of Harmony” discusses “the Symmetric System of Harmony (Type III).”Footnote 40 In this chapter Schillinger outlines a system whereby all progressions of chordal roots correspond to symmetrical divisions of one or more octaves. He supplies the possible constellations of root progressions given a root of C, shown in Example 11. The nomenclature in this example is rather opaque: Cx refers to interval cycles where “x” specifies descending intervallic quantities but not qualities. C7, for example, describes a cycle of descending sevenths (minor or major, depending on whether the composer chooses a whole tone or chromatic system, respectively). “-X” signifies ascending intervals: C-7 denotes ascending sevenths.Footnote 41 According to this method, all chordal root movements correspond to complete, partial, or embellished sets of symmetrically spaced pitches.

Example 11. Schillinger's symmetrically distributed roots ([1946] 1978, 396). Joseph Schillinger System of Musical Composition, Courtesy of Carl Fischer, LLC. All rights reserved. Used with Permission.

Schillinger adds that composers may both combine multiple symmetrical progressions and add passing or embellishing chords; his theory of symmetrical root movement provides only a basic harmonic structure. For brevity in my analyses, I adapt Schillinger's nomenclature for symmetrically spaced roots and use STx, where “x” corresponds to the number of roots that evenly divide an octave (ST = “symmetrical tonics”). Put differently, ST2 corresponds to a tritone, ST3 to major thirds, ST4 to minor thirds, ST6 to whole steps and ST12 to half steps.

Although Schillinger's method accounts for root movement of fifths by evenly dividing multiple octaves, Abrams appears to prefer symmetrical sets that fit within a single octave. This preference reflects the fact that root movement by fifths already comprises a prominent aspect of the jazz idiom with which Abrams was already fluent. Schillinger's system of harmony therefore augmented Abrams's harmonic knowledge by providing an alternate method of organizing root movement, rather than replacing his approach entirely.

Abrams's composition “Roots,” which appears on his 1975 solo recording Afrisong, provides a relatively clear demonstration of symmetrical root movement. The upper staff of Example 12 presents my transcription of the chords of the composition. The lower staff shows roots of these chords, bracketed to indicate symmetrical collections. “Roots” consists of five 4-measure phrases and features multiple constellations of symmetrical spaced roots. The opening five roots form ST6—F, A, Eb, Db, B. The root of the final chord of m. 4—Cmin7—departs from this collection but connects to the following two chords to form part of the complementary ST6 collection—C, Bb, Ab. I hear the Bmin6 chord in m. 6 as a return to the opening ST6 set (indicated by the arrow in Example 12). Measures 7 and 8 replicate the half-half-whole harmonic rhythm in mm. 5 and 6, and these three chords highlight the ST12 collection by deploying half-step root movement. This moment suggests that Abrams uses half-step root movement to announce ST12, helping disambiguate ST12 from other root progressions, even as ST12 could theoretically account for any collection.

Example 12. Symmetrical roots in Abrams's “Roots.” Transcription by author.

The four chords beginning in m. 9 similarly descend from Bb to G using stepwise motion through ST12, which then lead to a longer ascent using ST12 from E to B (the end of m. 12 to the beginning of m. 19). The final two measures smoothly reverse this progression motion using ST12, functioning as a kind of “turn around.”

Abrams's use of symmetrical roots in “Roots” generates a novel progression that eschews the typical root movements found in bebop and jazz “standards.” This novel root movement mitigates against any strong sense of harmonic function, which is reinforced by Abrams's exclusive use of minor seventh chords. Symmetrical root progressions thus emerge as the primary structural pillar of the piece, even as its melody operates more freely.Footnote 42

Conceptual Resonances between SSMC and Abrams

What made SSMC appeal to Abrams? Earlier I suggested that it helped Abrams develop his experimental practice, which functioned alongside his deep knowledge of the jazz idiom. In this section I offer two related conceptual resonances that further attest to SSMC's appeal to Abrams: the first concerns rhythm, the second, numbers.

Multiple sources demonstrate that Abrams regarded rhythm as the most important musical element, a stance mirrored in the pages of SSMC. Moran recalls that during his Schillinger-influenced lessons Abrams “explained that the essential aspect of music lies within the rhythm.”Footnote 43 Abrams notes in his pedagogical outline while teaching at the AACM school in Chicago that “first we organize ourselves rhythmically.”Footnote 44 Finally, during a composition workshop at the Banff Center in Canada in 1993 Abrams states that rhythm is the fundamental musical element.Footnote 45

SSMC contrasts with most other music theory texts by positioning rhythm as the most important aspect of music.Footnote 46 Schillinger even criticizes Western art music composers such as Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven for their apparent defective temporal coordination of multiple streams of music.Footnote 47 American music, for Schillinger, improves on this deficiency because of its connection to a different tradition:

A score in which several coordinated parts produce, together, a resultant which has a distinct pattern—has been a “lost art” of the aboriginal African drummers. The age of this art can probably be counted in tens of thousands of years! … Today in the United States, owing to the transplantation of Africans to this continent, there is a renaissance of rhythm. Habits form quickly—and the instinct of rhythm in the present American generation far surpasses anything known throughout European history.

This provocative passage acknowledges and emphasizes a long history of African music making, attributes the vitality of contemporary American music to the influence of African Americans, and exalts contemporary American music above Western art music—uncommon statements in Western music theory treatises! Simultaneously, however, it expresses deeply problematic and racist associations between blackness and “instinctual” rhythm, refers to an imaginary African past that Schillinger only knew through contemporaneous publications in comparative musicology, and ignores the violent schism produced by slavery. Abrams likely perceived these factors (and others), but perhaps Schillinger's praise for Black music positively impacted Abrams's regard for the text. Having noticed educational institutions’ erasure of Black people in their programs,Footnote 48 Schillinger's inversion of the oft-encountered dynamic between Western art music and Black music was conceivably encouraging.

Numerical representation also constitutes an important connection between Abrams and SSMC. Abrams describes a numerical process of scale construction in an outline of his composition classes for the AACM:

I take a tetrachord 2 + 2 + 1, C + D + E + F. We have to have a note to start from. That's the first four notes of the major scale. If we proceed with the major scale, from the F we get another 2, to G. From the G we get another 2, to A… . And then, from A to B another 2, and from B to C, a 1. So you have 2, 2, 1, with a 2 in the middle, then 2, 2, 1. That's the major scale, and you can start it on any note of the major scale… . [We] take this scheme and transfer it back to notation… . We're heading towards composing, personal composing. We're collecting these components, so we won't be puzzled by how to manipulate them.Footnote 49

This description demonstrates that numerical representation informed Abrams's pedagogical practice. Similarly, my discussion of interference reflects Schillinger's emphasis on numbers throughout SSMC. Importantly, Abrams aligns these theoretical “raw materials” or “components” with an emphasis on personalized creative practice: “We're heading towards composing, personal composing.”

Numerical representation has a special, additional meaning for Abrams. In an arresting portion of the AACM's foundational meetings, Abrams helps evaluate a proposed name for the group using numerology. Abrams states that the acronym, AACM, “would put a nine on us, initial-wise.” Trumpeter and AACM cofounder Phil Cohran defers to Abrams to provide the explanation to confused members, specifying that “this was your [meaning Abrams's] conversation, not mine.” Abrams replies that “‘A’ represents ‘1,’ ‘M’ represents ‘4,’ ‘C’ represents ‘3,’ M and C would be 7, and the two A's are one apiece. That's nine.” Nine, Abrams states, is “as high as you can go.”Footnote 50

In most versions of numerology, “expression numbers” describe talents and predilections. Expression numbers are calculated first by mapping the letters in one's name onto integers 1–9, where the alphabet “wraps around” this integer set; “C,” “L,” and “U” thus all correspond to the number 3. Numbers corresponding to each letter in the name then are summed, and any total greater than nine is similarly “wrapped around,” which equates to repeatedly subtracting nine until the total is less than ten. The total of Marc, for example, is seventeen, which reduces to eight (M = 4, A = 1, R = 9, C = 3; 4 + 1 + 9 + 3 = 17; and 17 - 9 = 8). Although the precise translations of expression numbers vary slightly across numerologists, the AACM's total of nine signifies traits often associated with collectivity and imagination—humanitarianism, creativity, generosity, and idealism. The number nine also often denotes openness to new experiences, trust in others, and a predilection for teaching. These values mirror the AACM's philosophy of community-based experimental music and art making, and the founding members seem acutely aware of this correspondence in their initial meetings.

The numerological meanings of Abrams's names are equally interesting. “Abrams” also totals nine—the Association's expression number is mirrored in its first president. “Richard” totals seven; a number that embodies a desire for truth and knowledge, an analytical mind, and a prediction for answers, philosophy, and science. It seems likely that Abrams noticed the implications of the expression number of his then-first name.

Abrams's adoption of the name “Muhal” in 1967 connects to a new black consciousness whereby African Americans modified or dropped “slave names”—names inherited from European slave-masters—and adopted names associated with Black culture.Footnote 51 Scholars such as Obiagele Lake and Annette J. Saddik connect naming and renaming to African Americans’ efforts to reclaim histories and subjectivities subjugated by colonialism and slavery, to creatively imagine a better future, and to signify on the “fiction” of a unified Black subjectivity.Footnote 52 Renaming can thus function as part of what Robin D.G. Kelley calls “freedom dreams”—“creative, expansive, and playful dreams of a new [and better] world.”Footnote 53

The numerological meaning of “Muhal” adds a complementary layer to these authors’ perspectives; it suggests that Abrams adopted the name as part of a creative imagining of a better future, expressed through numerology. Pianist and radio host Marian McPartland asked Abrams directly during his 1988 appearance on her show on National Public Radio, Piano Jazz, if his adoption of “Muhal” was for religious reasons. Abrams replies: “it was a numerical addition … having to do with numerology.”Footnote 54

The numerological “expression number” of “Muhal” is one (M = 4, U = 3, H = 8, A = 1, L = 3; 4 + 3 + 8 + 1 + 3 = 19; 19 – 9 = 10, 10 – 9 = 1).Footnote 55 That number has a profound numerological meaning: it is associated with leadership, individualism, ambition, and a pioneering spirit. There is therefore a striking symmetry between the AACM's and Abrams's respective expression numbers: if the AACM's numerological meaning is primarily concerned with collective creativity and idealism, then Abrams's adopted name represents the means of leading that collective toward that future. Abrams's self-renaming thus concatenates the above theorizations in terms of Black consciousness, persona creation, and imagined ideal futures with his belief in the power of numbers. It suggests that Abrams adopted “Muhal” to both represent personal qualities he felt that he already exhibited and creatively project an ideal future. His reverence for numbers, a stance shared by Schillinger, revolves around the imagining and projection of a better future via numerology.Footnote 56

Conclusion: Influences and Resonances

Greenwich Music House, an important site for the New York music scene since its founding in 1902,Footnote 57 served as the venue for a series of Schillinger-based composition lessons that Abrams gave to Jason Moran and other musicians in the late 1990s.Footnote 58 In a 2000 MTV interview, Moran reveals that “the rhythm was thoroughly worked out” for his composition “Fragment of a Necklace.”Footnote 59 My following analysis locates this rhythmic foundation in SSMC. This theoretical connection subsequently suggests a broader genealogy of Afrological engagement with music theory.

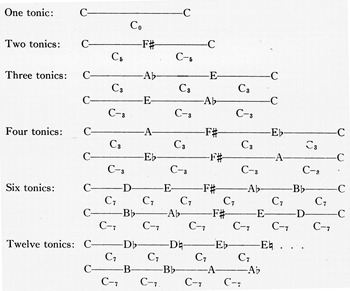

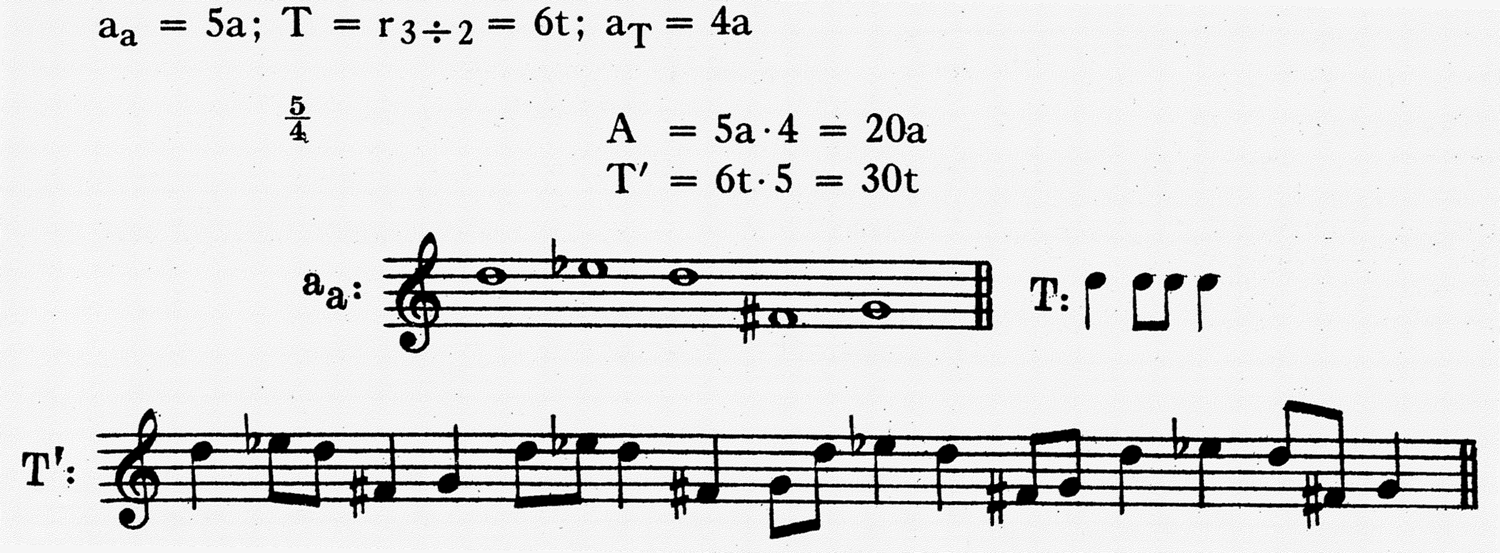

Schillinger's resultant rhythms issue from the overlay of two or more streams of regular pulses. Integers represent the duration of each stream's pulsations in terms of a given rhythmic unit. Although Schillinger uses a graphical system to represent both pulsation streams and resultants, I use conventional rhythmic notation for greater legibility. Example 13a shows the derivation of a resultant that employs periodicities of three and two, or r3÷2, using a basic rhythmic unit of sixteenth notes. The top and middle staves show the two periodicities: three sixteenths long on the upper staff and two sixteenths long on the lower one (which periodicity is “on top” does not influence the rhythmic result). Note that there are two iterations of the periodicity of three, and three iterations of the periodicity of two: a cross-relation that holds for any resultant with two constituent pulsation streams.Footnote 60 The third staff shows the rhythm that results—the “resultant rhythm”—from the overlay of these two streams; that is, every attack on the third line corresponds to an attack on one or more of the previous two lines. Schillinger represents resultants as a string of integers, where each number designates the duration of each attack in reference to an underlying common rhythmic denominator; that is, r3÷2 can be represented as 2+1+1+2 (Example 13a), r4÷3 can be represented as 3 + 1 + 2 + 2 + 1 + 3 (Example 13b), and r7÷5 can be represented as 5 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 1 + 5 + 1 + 4 + 3 + 2 + 5 (Example 13c). These numerical strings—what Schillinger calls “polynomials”—dissociate rhythms from any particular rhythmic division or meter: they may be placed in any metrical setting or use any duration as their primary unit. Put differently, any polynomial can be realized using eighth notes, eighth note triplets, quarter note quintuplets, half notes, or any other rhythmic unit, and placed into any meter.Footnote 61 All resultants are also palindromes, lending them a unique rhythmic character in any metrical setting.

Example 13. (a–c) Derivation of (a) 3÷2, (b) 4÷3, and (c) 7÷5 resultants.

“Fragment of a Necklace” uses six different resultant rhythms for its melody and bassline (Example 14). Square brackets segment the musical surface into resultants, which account for the rhythmic structure of the entire composition. I also indicate the resultant—in the form “a:b”—and polynomials. Moran's opening vamp utilizes r3÷2, or 2 + 1 + 1 + 2, realized as eighth notes in its lower part. Measures 3–6 use r4÷3, or 3 + 1 + 2 + 2 + 1 + 3, realized as quarter notes (Moran plays the eighth note at the end of m. 4 during the first iteration of the composition but omits it in subsequent iterations on this recording). Measures 7 and 8 use r5÷2, or 2 + 2 + 1 + 1 + 2 + 2, realized as quarter notes. Measures 9–13 use r5÷3, or 3 + 2 + 1 + 3 + 1 + 2 + 3, also realized as quarter notes. Moran distributes the 1+2 portion of this resultant between the bass and treble in measure 12 (an orchestration technique also covered in SSMC).Footnote 62 Measures 14–20 use r7÷6, or 6 + 1 + 5 + 2 + 4 + 3 + 3 + 4 + 2 + 5 + 1 + 6, realized as eighth notes. Moran consistently uses a triplet figure at the end of measure 18 instead of the two eighth notes dictated by the resultant. I interpret this figure as an embellishment, where the final C is an anticipation of the following downbeat. Measures 21–23 use r8÷3, or 3 + 3 + 2 + 1 + 3 + 3 + 1 + 2 + 3 + 3, realized as eighth notes. Finally, the opening r3÷2 vamp returns to bookend the composition, first in the melody and then back in the bass. Moran's waltz setting of these resultant rhythms produces an arresting, syncopated feel, where the music oscillates between reinforcing and obscuring the mostly triple meter.

Example 14. Resultants in Moran's “Fragment of a Necklace.” Transcription by author.

This link between Abrams and Moran portends a much broader genealogy of music-theoretical engagement by African American creative musicians. I theorize this varied and complex genealogy as “fugitive music theory,” drawing on work from Black studies and African American studies that explores resonances between the figure of the fugitive slave and Black life after Emancipation.Footnote 63

What unites this music theoretical work is its drive toward Black freedom and liberation; yet unrealized, it subsists in “the interval between the no longer and the not yet, between the destruction of the old world and the awaited hour of deliverance.”Footnote 64 Jarvis R. Givens powerfully argues that Black education disrupts the “chattel principle,” drawing on Frederick Douglass's recognition that literate slaves were akin to fugitive slaves, by countering racist representations of Black life.Footnote 65 Fugitive music theory similarly contradicts pejorative descriptions of Black musicians as relying only on natural ability, inspiration, or improvisation. I argue that ignoring Black music's theoretical and intellectual components mirrors this tradition of denying Black people's cognitive abilities and subjectivity.

The phrase “American music theory” usually distinguishes the field's work from activity in Europe, but its circumscribed frame mirrors longer American trends of refusing personhood and citizenship to Black Americans. Even Nicholas Cook's “broadest-brush historical interpretation of music theory” restricts itself to white men such as Rameau, Dahlhaus, Schenker, and Schoenberg.Footnote 66 If this is the broadest interpretation of music theory, we have a lot of work to do.

Fugitive music theory is my term for genealogies of music-theoretical activity that participate in larger mechanisms of Black cultural production, affirm Black life and agency, and critique white supremacy and its attempts at containment.Footnote 67 The work in this genealogy helps imagine new musical worlds that nourish social and creative freedom for Black people, an important contrast with traditional music theory. Abrams's adaption of Schillinger was in service of his broader experimental practice. Fugitive music theory hence also rejects narrow definitions of Black music in terms of genre and method of creation.Footnote 68 Finally, Abrams's example also demonstrates that fugitive music theory appropriates conventional music theoretical traditions when advantageous. It thus does not completely reject traditional musical theory but incorporates aspects of it to serve new ends.

Fugitive music theory often occurs outside of typical institutions for music theory, reflecting Stefano Harney and Fred Moten's notion of “Black study.”Footnote 69 It instead occurs on the street or on public transit between rehearsals and gigs, after hours in clubs, dressing rooms, or tour buses, in rehearsal and recording spaces, and countless other venues where artists work on their music, either on their own or with others. For Abrams, these sites include Experimental Band rehearsals, his apartments, Greenwich Music House, and AACM meetings.

Finally, an additional meaning of “fugitivity” refers to the way this work resists (i.e., escapes) appropriation and assimilation into white supremacist structures and framings that avoid wrestling with the systemic issue of who and what counts as music theory in the first place. Philip Ewell's and Ellie Hisama's recent, powerful calls for music theory to address its parochialism in terms of epistemology, repertoire, and membership generated a new wave of discussions, workshops, symposia, and (in some cases) amendments.Footnote 70 Structural change toward greater equity, however, requires more sustained efforts. Fugitive music theory functions as part of larger calls for radically restructuring who and what counts as music theory, learning goals, curricula, methods of assessment (from undergraduate courses to promotion and fellowship applications), and places of publication, as well as confronting the white supremacist roots of the field. It also means addressing that fact that most music theorists looking to discuss Black creative practice will do so as outsiders and thus must not simply pillage work by Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of color for their own professional benefit, a point forcefully made by Dylan Robinson.Footnote 71

In this article I try to avoid using music theory and analysis to “explain” Black creative practice. Instead, I ask us to consider music theory's fragmentary but important role in Black musical traditions. When I began this research as a graduate student, I told Abrams that I wanted to accurately represent him and his music in my writing, referencing white academics’ many years of misrepresenting Black musicians. He replied that it was not my job to represent him, that he and his work are their own representations. Rather, he suggested, I should discuss and analyze his music with integrity, and that what I find represents my engagement with his work. This rejoinder deemphasizes narratives of representation or translation, supplanting it with a multi-voiced, relational mode of engagement. I hope that my scholarship offers analytical and theoretical perspectives that complement Abrams's extraordinary work, that it gestures toward larger networks of music theory that challenge academic music theory's insularity, and prompts greater discussion of the roles of fugitive music theory in other corners of music studies.

Marc E. Hannaford is a music theorist who thinks about performance, identity, and improvisation. Some of his other publications appear in Theory & Practice, The Oxford Handbook of Public Music Theory, Music Theory Online, and Sound American. He is also an improvising pianist, composer, and electronic musician who has performed and/or recorded with Tim Berne, Ingrid Laubrock, Tom Rainey, Tony Malaby, and William Parker.