Impact statement

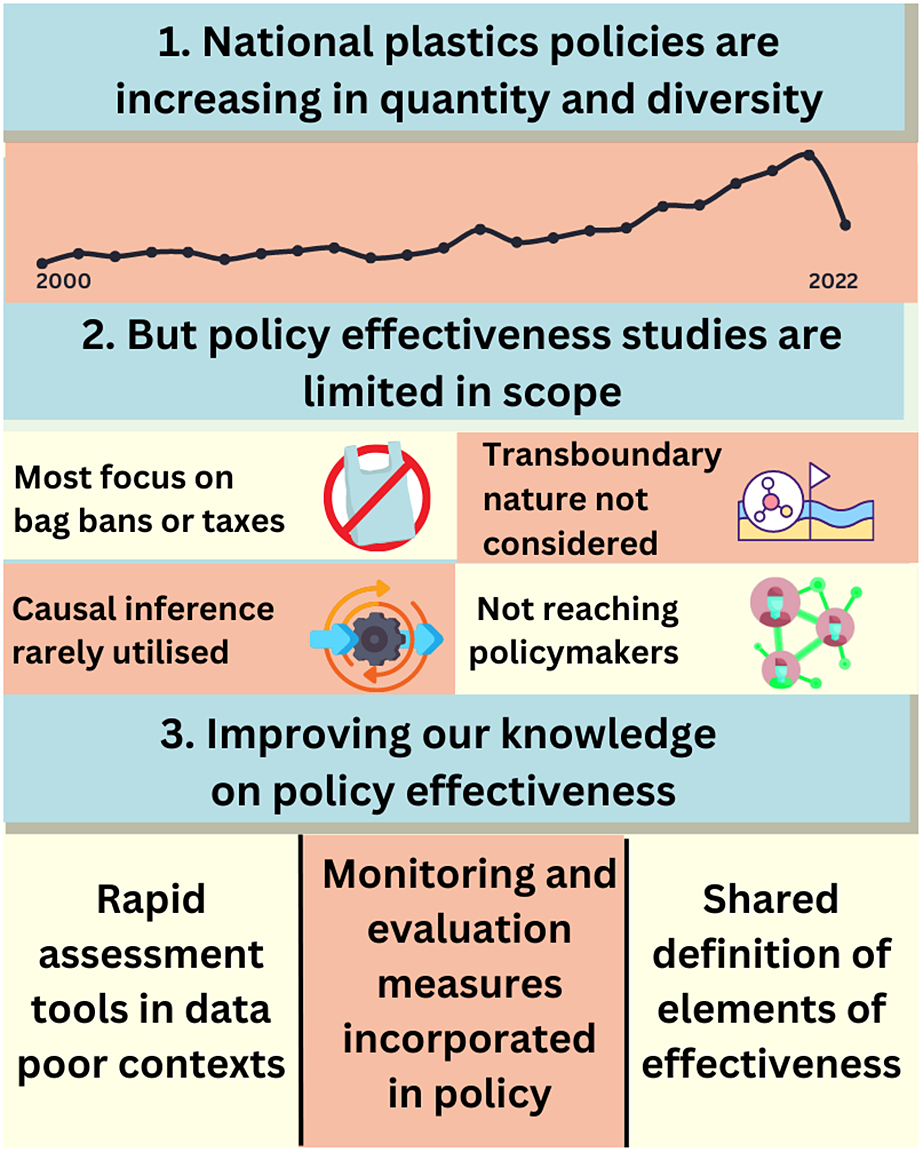

The global plastics crisis, which is intertwined with climate, health, labour and justice crises, threatens socioecological systems globally. As such, a comprehensive and coordinated response from all sectors and stakeholders is required for this issue to be meaningfully resolved. National governments, in particular, have a significant role to play through both domestic policy and programs as well as international coordination via multilateral, regional, and global agreements, including the pending instrument to end plastic pollution. Robust knowledge of policy effectiveness, including measurements of social, ecological and economic outcomes of policy implementation, a determination of unintended consequences, and the use of causal methods is one critical element for informing and adapting the policy landscape. The available evidence suggests, however, that the increase in national policy adoption and implementation is not matched with an increase in knowledge of policy effectiveness. Likewise, there is limited evidence on policy formulation to indicate the extent to which available effectiveness data is informing policy, suggesting that there remains a science to the policy gap. Looking forward, significant paradigm shifts in how the global community of practice formulates, designs, implements, monitors and evaluates national plastics policy are required to ensure that the problems associated with the plastics life cycle are addressed.

Introduction

Plastics are a relatively new material consisting of synthetic polymers, growing tremendously in their use within the last 70 years. To date, our collective ability to develop new polymers and uses for plastics far exceeds our ability to manage it as it grows in volume (Geyer et al., Reference Geyer, Jambeck and Law2017; Lau et al., Reference Lau, Shiran, Bailey, Cook, Stuchtey, Koskella and Palardy2020). This has resulted in the continued and projected increase in mismanaged plastic waste globally (Lebreton and Andrady, Reference Lebreton and Andrady2019). Projections show an upward trend in the release of plastics into the aquatic environment even under ambitious strategies, with estimates for 2016 between 19 to 23 million tons annually, rising up to 53 million tons per year by 2030 (Borrelle et al., Reference Borrelle, Ringma, Law, Monnahan, Lebreton and McGivern2020; Lau et al., Reference Lau, Shiran, Bailey, Cook, Stuchtey, Koskella and Palardy2020). These projections highlight the need to go beyond current commitments to manage plastics along the entire lifecycle. It is becoming widely accepted that a systemic and concerted effort in policy change is needed to enable the reduction in plastic pollution (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Shiran, Bailey, Cook, Stuchtey, Koskella and Palardy2020; Fletcher et al., Reference Fletcher, Roberts, Shiran and Virdin2021).

To enact change, policies need to enable effective infrastructure, services and behaviour for waste management (Timlett and Williams, Reference Timlett and Williams2011). Infrastructure refers to the assets utilised in waste management to sufficiently manage the demands of the population, such as treatment facilities and bins. Services include collection of waste and street cleaning, which are provided either through formal or informal waste management structures. Behaviour enables the effective utilisation of services and infrastructure, and includes not littering, sorting waste or utilising deposit return schemes, among others. Transferability of successful policy approaches across regions can be difficult depending on the infrastructure, service availability and use behaviours across areas. This variability can make it difficult to characterise and assess the enabling conditions for effective policy approaches that are transferable across regions. As a result, an uncoordinated and fragmented policy landscape currently governs plastics along the lifecycle (OECD, 2022). Research and advocacy suggest that national-level policy responses will be most effective if they address all stages of the plastics lifecycle, target the biggest sources of all kinds of plastic pollutants including harmful additives, and are, to the best extent possible, coordinated and consistent between countries (March et al., Reference March, Roberts and Fletcher2022b; Syberg, Reference Syberg2022). Many advocates believe that an upstream approach which targets the volume and rate of production will be key (EIA, 2022), while the private sector and some governments are approaching waste management and end-of-life approaches, particularly through increased recycling, as the principal solution to this problem (Diana et al., Reference Diana, Reilly, Karasik, Vegh, Wang, Wong and Virdin2022a).

A number of international frameworks or approaches exist that address plastics governance such as the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions; the World Trade Organisation Informal Dialogue on Plastic Pollution and Environmentally Sustainable Plastics Trade (IDP); the EU Waste Directive; and Voluntary Environmental Approaches (e.g. Ellen Macarthur Foundation Global Commitments) for corporate responses. In February 2022, to facilitate an accelerated and concerted effort to tackle the plastic pollution problem, a resolution for the development of a legally binding instrument to end plastic pollution was passed during the fifth session of the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEP, 2022a). Through 2024, negotiations will be undertaken at an international level to develop an instrument that will address plastics across the whole lifecycle (cradle to grave), with the intention of ending plastic pollution. All of these approaches, and especially the international legally binding instrument, aim to develop effective policy, to the best extent possible, and minimise unintended consequences. All of these international governance mechanisms affect national plastics policy-making, by driving the decisions made at the national level. This article seeks to provide the current state of knowledge of plastics policy effectiveness to support these agendas.

The field of plastics policy is quickly evolving with new policy approaches and innovations regularly emerging as components of the solutionscape (Schmaltz et al., Reference Schmaltz, Melvin, Diana, Gunady, Rittschof, Somarelli and Dunphy-Daly2020; Karasik et al., Reference Karasik, Bering, Griffin, Diana, Laspada, Schachter, Wang, Pickle and Virdin2022; Moss et al., Reference Moss, Gerken, Youngblood and Jambeck2022). Therefore, the state of knowledge on plastics policy and its effectiveness requires regular updating to account for new policies, policy types, technology, social considerations and acknowledgement of unintended consequences. A more comprehensive assessment of the impacts and effectiveness of policies and interventions will enable improved policy responses moving forward.

A number of institutions focus on assessing plastic policies including the Global Plastics Policy Centre at the University of Portsmouth; Duke University’s Plastic Pollution Working Group; the World Resources Institute; The Norwegian Institute for Water Research (NIVA) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). However, because effectiveness studies are expensive and resource intensive, they are conducted infrequently (Fürst and Feng, Reference Fürst and Feng2022) and inconsistently (Schnurr et al., Reference Schnurr, Alboiu, Chaudhary, Corbett, Quanz, Sankar, Srain, Thavarajah, Xanthos and Walker2018), which engenders a chasm of cracks and gaps. This article reviews the existing literature to discuss the gaps that exist in understanding what makes national plastics policy effective, and provides potential solutions to create a more complete picture of plastics governance that is effective in practice.

The effectiveness landscape

To date, the majority of studies measuring effectiveness of national policy have focused on bag bans or economic instruments such as taxes. This could be attributed to the early adoption of such interventions, such as the Bangladesh plastic bag ban of 2002 (Muposhi et al., Reference Muposhi, Mpinganjira and Wait2022), and the plastic bag tax in Ireland in 2002 (Convery et al., Reference Convery, McDonnell and Ferreira2007). The effectiveness of bag bans and taxes has been frequently studied (see Xanthos and Walker, Reference Xanthos and Walker2017; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Holmberg and Stripple2019) compared to other policy types such as extended producer responsibility. Plastic bag bans have been reviewed in sub-national (e.g. San Francisco; Romer, Reference Romer2010), national (e.g. Australia; Macintosh et al., Reference Macintosh, Simpson, Neeman and Dickson2020), Nepal; Bharadwaj et al., Reference Bharadwaj, Baland and Nepal2020) and global (Clapp and Swanston, Reference Clapp and Swanston2009) levels. Taxes on plastic bags have also been reviewed frequently from those implemented in South Africa (Dikgang et al., Reference Dikgang, Leiman and Visser2012), to Ireland and Denmark (Muphoshi et al., Reference Muposhi, Mpinganjira and Wait2021). Findings of the effectiveness of bag bans and taxes generally hinge on awareness raising, access to suitable alternatives, sufficient moratorium or phasing out of products and adequate enforcement or penalties as important enabling factors (March et al., Reference March, Salam, Evans, Hilton and Fletcher2022a). While valuable to have evidence of where bag bans and taxes have worked or failed, and why, these policies target specific products, such as bags only of a certain thickness, and only at the production, trade and consumption stages, often neglecting the wider implications of plastics across the value chain and in many instances displacing the impacts with alternatives that have equal or more harmful impacts on the environment (March et al., Reference March, Salam, Evans, Hilton and Fletcher2022a; Muposhi et al., Reference Muposhi, Mpinganjira and Wait2022).

When delving deeper into the nature of existing effectiveness studies, causal inference methods which relate the observed outcomes directly to the implementation of a policy and are considered more scientifically valid determinations of policy impact are rarely used (Diana et al., Reference Diana, Vegh, Karasik, Bering, Caldas, Pickle, Rittschof, Lau and Virdin2022b). The majority of evaluations are based on simple attribution and correlational approaches which measure outcomes in the geographic location of the policy’s area, lacking a control group against which the outcomes of the policy can be observed. This means not only that the resulting changes (or lack thereof) cannot be solely accredited to the policy under evaluation (Ferraro and Hanauer, Reference Ferraro and Hanauer2014) but also that the evaluation fails to account for the transboundary nature of plastics (Parajuly and Fitzpatrick, Reference Parajuly and Fitzpatrick2020). This is highlighted by Diana et al. (Reference Diana, Vegh, Karasik, Bering, Caldas, Pickle, Rittschof, Lau and Virdin2022b), where only 5 of 149 studies on the effectiveness of policies, predominantly on bags and, in a few instances, other single-use plastic products, used causal inference methods; the other 144 based their findings predominantly on plausible attribution. This emphasises the need for robust, evidence-based effectiveness evaluations at the national level.

There are tools available for formally measuring waste baselines, sources and composition to inform policy-making, such as the Circularity Assessment Protocol by the Jambeck Research Group at the University of Georgia (Circularity Informatics). Knowledge of modelled costs and benefits, based on existing measures of effectiveness, is also used as an input in Pew Charitable Trusts and Systemiq Breaking the Plastic Wave ‘Pathways’ Tool (2022), which can support decision-making by weighing the tradeoffs of various policy approaches. However, there are no universally used methodologies to evaluate the effectiveness of policies that use advanced approaches to understanding causality. Tools and resources for evaluating effectiveness by measuring outcomes correlationally are in their nascent stages, and there is no harmonised approach to evaluating effectiveness. Researchers at the Global Plastics Policy Centre have developed an open-access, evidence-based framework for evaluating the effectiveness of plastic policies, across a wide range of policy areas (March et al. 2022). The framework not only includes absolute performance (e.g. how much reduction in plastic pollution has been seen solely attributed to the policy in question) but also evaluates the contributing factors and steps taken in the formulation of policy such as stakeholder consultation, socio-economic burden, long-term financing arrangements and enforcement mechanisms. To date, over 150 policies have been reviewed by the Global Plastics Policy Centre, with an aim to understand what barriers and enablers exist for each policy type in different national and sub-national contexts. A key finding of their research is that over 30% of policies have insufficient evidence to draw any conclusions about policy performance, and a further 25% of policies have a severely limited evidence base against which they can be evaluated. This is postulated to be a result of insufficient monitoring and evaluation and a lack of transparency and disclosure, rather than being too recent to evaluate, where more than half of these policies had been promulgated for more than 3 years (March et al., Reference March, Salam, Evans, Hilton and Fletcher2022a).

A global lack of monitoring and reporting to generate sufficient evidence on policy effectiveness thwarts attempts to progress in this space (Kedzierski et al., Reference Kedzierski, Frère, Le Maguer and Bruzaud2020). Consistently March et al. (Reference March, Salam, Evans, Hilton and Fletcher2022a) found that there is severely limited information on stakeholder engagement in the policy development process, the social, economic and public health burdens as a result of the policy, sustainable financing and monetary costs of implementation, and the destination of waste (when related to downstream collection and recycling policies) (March et al., Reference March, Salam, Evans, Hilton and Fletcher2022a). A further pervasive evidence gap exists regarding the effect of changes to consumer behaviour on recycling, landfilling and incineration rates. Northern et al. (Reference Northern, Nieminen, Cunsolo, Iorfa, Roberts and Fletcher2023) identify patterns in consumer behaviour and how this relates to disposal, but highlight the need for standardisation in consumer behaviour evaluation approaches to improve the evidence needed to inform effective policy.

Barriers to understanding effectiveness

Developing approaches that address the scale of the problem is inhibited by the fact that there is very limited knowledge and useful data on the plastics economy, including how much plastic is synthesised and enters the plastics system annually as data on production is generally not disclosed (Geyer et al., Reference Geyer, Jambeck and Law2017; March et al., Reference March, Roberts and Fletcher2022b), porous trade borders that allow for significant influxes of plastic are not always accounted for (either through poor reporting mechanisms or untargeted reporting on plastic influxes into national systems), and national data is unreliable (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2022). This, alongside key missing data on how much plastic we actually need in our economy to maintain current living standards, limits an accurate understanding of the scale of interventions needed at the national level. The basis for the current understanding of the plastics economy relies on estimates and models, which while meritorious and based on sound science and expertise, may under- or over-represent the reality due to the high uncertainty that exists within the models. Having the right scale of an intervention is an enabling factor for effective policy (Fletcher et al., Reference Fletcher, Roberts, Shiran and Virdin2021; March et al., Reference March, Salam, Evans, Hilton and Fletcher2022a), to ensure that the policy is able to account for the varying levels of interaction across the plastics value chain.

As indicated by Nielsen et al., “the whole plastics life cycle is political, but it has not yet been equally politicised” (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Holmberg and Stripple2019, p. 2), meaning that plastic waste and pollution (i.e. downstream points of the plastics lifecycle) receive the most emphasis in scientific literature, public media and policy approaches. A significant portion of the national policy landscape focuses on a single item, or group of items at select stages of the plastics lifecycle (Diana et al. Reference Diana, Reilly, Karasik, Vegh, Wang, Wong and Virdin2022a, Reference Diana, Vegh, Karasik, Bering, Caldas, Pickle, Rittschof, Lau and Virdin2022b). By comparison, very few upstream or whole-lifecycle policies that target or restrict plastic production more comprehensively have been implemented. Such policies can utilise a wide menu of instruments such as taxes on the production of polymers from virgin feedstocks, removing subsidies on fossil fuels, tax incentives on reuse models, eco-modulated extended producer responsibility fees, standards for compostable and biodegradable materials and binding targets for recycled content in polymer production (UNEP, 2022b). This uneven distribution of focus creates a disparity in the policy approaches applied, and creates an unequal distribution of attention given, where ultimately having limited policy approaches may prevent a proliferation in evaluations of diverse or emerging policies’ effectiveness (Karasik et al., Reference Karasik, Bering, Griffin, Diana, Laspada, Schachter, Wang, Pickle and Virdin2022).

Furthermore, while recent research (Karasik et al., Reference Karasik, Bering, Griffin, Diana, Laspada, Schachter, Wang, Pickle and Virdin2022) indicates that policy responses are diversifying to target a wider range of plastic types, “certain types of plastic pollutants still appear to be largely ignored in policy-making, despite their known contributions to the global problem” (p. 13). The authors note the example of microplastics, which, widely understood to have harmful impacts on the environment (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Thompson and Galloway2013; de Souza Machado et al., Reference de Souza Machado, Lau, Till, Kloas, Lehmann, Becker and Rillig2018) and human health (Prata et al., Reference Prata, da Costa, Lopes, Duarte and Rocha-Santos2020a), have yet to be addressed in products such as toothpaste (non-rinse-off microbeads), clothing (microfibres) and tyres (abrasion), though microbeads have been phased out in rinse-off products in a number of countries (Anagnosti et al., Reference Anagnosti, Varvaresou, Pavlou, Protopapa and Carayanni2021). Ultimately, there appears to be an inherent disconnect between science and policy.

Information on impacts, which policy approaches work and which do not is at present, are not reaching policymakers in an impactful way. This could be due to constantly changing political cycles, political biases and vested interests, and significant variations in the standards for defining evidence across scientific fields and policy domains, and the absence of metrics for effectiveness (Hallsworth et al., Reference Hallsworth, Egan, Rutter and McCrae2018; Ruggeri et al., Reference Ruggeri, Linden, Wang, Papa, Afif, Riesch and Green2020). Scientists have a responsibility to improve how they communicate evidence to decision-makers and the general public (Ruggeri et al., Reference Ruggeri, Linden, Wang, Papa, Afif, Riesch and Green2020) alongside the need for greater transparency in how policies are implemented and monitored, so that robust evaluations of effectiveness can be undertaken (March et al., Reference March, Salam, Evans, Hilton and Fletcher2022a).

Failure of evidence to meaningfully reach the public and decision-makers might be compounded by the lack of a unified definition of effectiveness. Existing evaluations of effectiveness studies often measure isolated outcomes of policy implementation, such as change in consumption of the plastic type (e.g. plastic bags) targeted by policy, change in recycling rates, or change in the volume and composition of litter sampled during clean-up events. While these measurements are important indicators of policy effectiveness, policies may also have varied impacts on broader social, economic and ecological systems. A small proportion of the effectiveness literature includes additional dimensions of policy effectiveness (Karasik et al., Reference Karasik, Bering, Griffin, Diana, Laspada, Schachter, Wang, Pickle and Virdin2022), and are described both quantitatively and qualitatively. Some studies demonstrate unintended consequences of policy implementation, for example where the purchase of small and medium-sized plastic garbage bags increases following a plastic bag prohibition, diluting the effect of the policy on overall plastic bag reduction. In addition, implemented policies may have disproportionate impacts on vulnerable groups. In a study in Morocco (El Mekaou et al., Reference El Mekaou, Benmouro, Mansour and Ramírez2021), researchers found that a black market for plastic bags developed in informal markets after the implementation of a bag ban. Plastic bags, now only available through an illicit market, became costlier than their legal predecessors, and disproportionately burdened r small and medium-sized vendors participating in those markets. Likewise, presumably the black market dampened the effect of the ban on mitigating waste from plastic bags. Similarly, opposition to a comprehensive single-use plastics ban in Mexico City, whereby feminist groups noted that low-income menstruating people are unable to access non-plastic alternatives to menstrual hygiene products (Griffin and Karasik, Reference Griffin and Karasik2022), demonstrates the potential social and economic implications of policy that extend beyond plastic consumption rates. Because there is not yet a common definition of policy effectiveness that encompasses the varied effects of policy, studies and characterisations of effectiveness may not account for the differing social, ecological and economic outcomes of a given policy.

There are a number of emerging issues not fully included in evaluations of policy development or effectiveness. COVID-19 presented new challenges to plastic pollution and policy implementation. National lockdowns shut down or reduced waste management practices and altered producer and consumer behaviours (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Stringfellow and Williams2020; Winton et al., Reference Winton, Marazzi and Loiselle2022). Some regions delayed or rescinded single-use plastic bans in an effort to reduce the transmissibility of the virus (Prata et al., Reference Prata, Silva, Walker, Duarte and Rocha-Santos2020b). Globally, there was an increased need for personal protection equipment and plastic dividers to aid with maintaining a safe distance. National legislation and World Health Organisation recommendations on mask utilisation resulted in increased disposable mask consumption and shifts in litter composition, with increases in mask and glove litter measured in terrestrial and marine environments (World Health Organization, 2020; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Phang, Williams, Hutchinson, Kolstoe, de Bie, Williams and Stringfellow2022). Behaviour changes during the pandemic have resulted in an overall increase in single-use plastic consumption (Kitz et al., Reference Kitz, Walker, Charlebois and Music2022; Winton et al., Reference Winton, Marazzi and Loiselle2022). This pandemic highlights both the importance of plastic and the need to ensure policies prevent, or at least account for, unintended consequences resulting in plastic mismanagement to ensure that they are effective.

The plastics economy is transboundary (De Silva et al., Reference De Silva, Doremus and Taylor2021), and the impacts of pollution across the lifecycle can be seen in a wide range of external areas. Yet, policies to manage plastics to date have been implemented in a plastics silo that fails to take into consideration the interactions of plastics with biodiversity, climate, labour and international trade. As a result, effectiveness evaluations also do little to account for these considerations. For example, linking climate change with plastic mismanagement and utilisation is a rapidly growing area of study (Stoett and Vince, Reference Stoett and Vince2019; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Huang, Che, Song, Zeng and Zhang2020; Zhu, Reference Zhu2021; Ford et al., Reference Ford, Jones, Davies, Godley, Jambeck, Napper and Koldewey2022) that has yet to be incorporated into plastics policy development or effectiveness evaluations. Plastics are primarily produced from fossil fuels, and at all steps within their lifecycle (extraction, refining, production, manufacture, transport and disposal) contribute to carbon emissions (Hamilton and Feit, Reference Hamilton and Feit2019; Zhu, Reference Zhu2021) and air pollution. This presents a missed opportunity where the burgeoning number of emerging plastics policies (Karasik et al., Reference Karasik, Bering, Griffin, Diana, Laspada, Schachter, Wang, Pickle and Virdin2022) and the forthcoming international legally binding instrument to end plastic pollution have the potential to address a myriad of other issues and meet national and international targets in other arenas if carefully designed to account for the synergies between plastics and climate change, biodiversity, labour and international trade. This could mean concurrently addressing the UN SDGs (Walker and Fequet, Reference Walker and Fequet2023), the High Seas Treaty (Lothian, Reference Lothian2023), the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (Cooke et al., Reference Cooke, Harrison, Thieme, Landsman, Birnie-Gauvin and Raghavan2023) and the Paris Climate Agreement (Farrelly et al., Reference Farrelly, Borrelle and Fuller2021).

Ways forward

Significant obstacles and barriers exist in working towards evaluating effectiveness of plastic policy as well as consistent evidence gaps. It is critical that in the context of the development of an international legally binding instrument to end plastic pollution, despite these persistent gaps, ambition in plastics policy is not deterred. Ambition is essential to ensure interventions can have meaningful impact, and do not maintain the status quo in relation to plastic pollution (March et al., Reference March, Roberts and Fletcher2022b). This is facilitated by having measurable and time-bound targets in policy formulation by which to measure effectiveness (March et al., Reference March, Salam, Evans, Hilton and Fletcher2022a). Ambition in this context can also be realised by moving towards systemic policies, rather than focusing on contemporary common measures such as bans and taxes.

Given the identified constraints of policy effectiveness reviews and the intensive resource requirements to undertake such comprehensive reviews (Fürst and Feng, Reference Fürst and Feng2022), and in the absence of more efficient methods at this point in time, lessons from other environmental management approaches could be explored. Rapid assessment tools such as those used in fisheries management for evaluating implementation (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Anderson, Chu, Meredith, Asche, Sylvia and Valderrama2015; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Karasik, Stavrinaky, Uchida and Burden2019) could be adapted to understand, in data-poor contexts, whether plastics policies are effective in practice by iteratively conducting surveys on the perceived performance of a given policy, understanding performance to include ecological (e.g. has there been a change in plastic consumption?), economic (e.g. has there been a change in the number of jobs?) and social (e.g. has there been a change in exposure to harmful chemicals?) outcomes. Such a survey is conducted on individuals (rather than sample populations) representing stakeholder groups at regular intervals (e.g. every 3 years) to allow for variations of perceived effectiveness across diverse perspectives and to enable consistent monitoring of outcomes over time.

Ultimately, plastics policies should include clearly defined monitoring and evaluation measures to assess effectiveness, which are agreed upon by stakeholders at the outset, and some do. These elements are currently missing from most plastics policies, which creates ambiguity in claims of policy success and undermines any attempt to refine policies based on current performance (March et al., Reference March, Salam, Evans, Hilton and Fletcher2022a). Efficient monitoring and evaluation not only allow a nation to track progress but also offer the potential to unlock investment, particularly in areas where progress is recorded. The gold standard for evaluating effectiveness would be through a harmonised, causal inference approach. Likewise, metrics or indicators for effectiveness should be consistent across and within policy types and regions to enable comparison and transferability.

The UNEA 5.2 agreement to develop an international legally binding instrument to end plastic pollution (UNEP, 2022a, 2022b) has the potential to pave the way for improved plastics policy effectiveness, particularly acting as a critical point for informing the direction of national plastics policy. Central to the success of the treaty will be offering harmonised or standardised effectiveness evaluation approaches, to measure progress and refine policies (March et al., Reference March, Roberts and Fletcher2022b). As evidenced throughout this review, at present, much of our approach to dealing with plastic pollution is operating with only partial information, which constrains effective action and the scale-up of transferable actions.

In summary, the road to effective plastics policy necessitates a paradigm shift towards a system in which climate, health, labour and other policies are developed in harmony with plastics policy, and integrates effectiveness evaluations to provide an evidence-based understanding of what works in practice. A broader understanding of effectiveness, which integrates policies across the plastics lifecycle, is imperative in creating effective solutions to plastic pollution.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2023.13.

Data availability statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contribution

Conceptualisation: A.M., R.K.; Investigation: A.M., R.K., K.R., T.E.; Writing – original draft: A.M., R.K., K.R., T.E.; Writing – review and editing: A.M., R.K., K.R., T.E.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

No accompanying comment.