Northern Paiute is a member of the Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family. It is spoken across the Great Basin in the western United States – from Mono Lake in California, on the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada, through western Nevada and into southeastern Oregon and southwestern Idaho, as well as in a discontinuous region in southeastern Idaho by the Bannock. There are, according to Golla (Reference Golla2011), about 300 first-language speakers of Northern Paiute. In this illustration, we describe the language's Mono Lake variety.

While some aspects of northern varieties of Northern Paiute have been described – e.g. phonetics (Waterman Reference Waterman1911, Haynes Reference Haynes2010), lexicon (Liljeblad et al. to appear), grammar (Liljeblad Reference Liljeblad1966, Snapp, Anderson & Anderson Reference Snapp, Anderson, Anderson and Langacker1982, Thornes Reference Thornes2003) – previous documentation of Mono Lake Northern Paiute is limited to a few word lists collected in the first part of the 20th century (Lamb n.d.; Merriam Reference Merriam1900–1938, Reference Merriam1903–1938) and our own fieldnotes and recordings. The variety of the language spoken at Mono Lake and immediately to the north (in present-day Bridgeport and Coleville, California, and Sweetwater, Nevada) diverges from more northerly ones in important ways. It preserves a number of typologically interesting phonological contrasts, and its morphology and lexicon differ significantly (Babel et al. to appear). There are no more than seven speakers, the youngest of whom is middle-aged.

The data presented here come from a single female speaker, born in 1921, who learned Mono Lake Northern Paiute alongside English in her childhood. She used the language with her mother and grandmother until they died, after which she has used English almost exclusively in her daily life. Recordings were made in a quiet room of the Bridgeport senior citizens’ center with a Marantz PMD670 solid-state recorder and a head-mounted AKG microphone.Footnote 1 The orthographic system we use, which we designed for the Mono Lake Northern Paiute community, is phonemic and generally maintains the correspondence between one sound and one symbol.

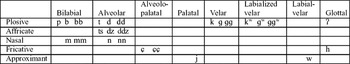

Consonants

Mono Lake Northern Paiute has 25 consonants, shown in the chart below.

These consonants contrast in seven places and five manners. The oral plosives exhibit a three-way contrast between what are traditionally called lenis, voiced fortis, and fortis realizations. Fricatives and nasals exhibit a two-way contrast between lenis and fortis realizations. These contrasts are illustrated by the following near-minimal pairs:

(1)

The contrast between lenis, voiced fortis, and fortis consonants only occurs in word-medial position. It is neutralized word-initially, as we discuss below.

Plosives

Mono Lake Northern Paiute's unique three-way contrast is manifested acoustically in closure duration, aspiration duration, and voicing during the closure interval. This contrasts with the typical textbook usage where ‘lenis’ and ‘fortis’ are defined in terms of respiratory or articulatory energy (Ladefoged & Maddieson Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 95–98).

The lenis plosives have a shorter closure duration and trend toward shorter aspiration duration. In running speech, they often surface as voiced fricatives, [β] or [ɣ], in the case of bilabial and velar plosives, or as a voiced tap, [ɾ], in the case of alveolar plosives:

(2)

The lenis plosives contrast with the voiced fortis and fortis plosives in aspiration and closure duration, as shown in Figure 1. Voiced fortis and fortis plosives overlap, with considerably longer aspiration and closure durations. These latter categories, in turn, contrast with one another in the presence or absence of voicing during the closure. As the pair of spectrograms in Figure 2 shows, the (voiced fortis) velar closure of /puɡɡu/ ‘horse’ shows voicing through the closure, while the (fortis) closure of /tuku/ ‘flesh, skin’ does not.

Figure 1 Lenis plosives (duration: M = 64, SD = 27; aspiration: M = 7, SD = 13) contrast with voiced fortis plosives (duration: M = 151, SD = 26; aspiration: M = 24, SD = 12) and fortis plosives (duration: M = 163, SD = 28; aspiration: M = 33, SD = 15) in aspiration and closure duration. For the lenis plosives, closure duration either refers to the actual duration of the closure or, when they have lenited to a fricative or approximant, to the duration of the approximation of articulators.

Figure 2 Voiced fortis and fortis velar plosives contrast in voicing during closure.

As we mentioned above, lenis, voiced fortis, and fortis plosives only contrast word-medially. In word-initial position, the contrast is neutralized. There are no word-final consonants.Footnote 2 Generally, word-initial plosives correspond most closely to the fortis category. They are realized as voiceless aspirated stops. On occasion, strong prevoicing does occur, most frequently with inalienable noun stems uttered in isolation. Since these nouns, in spontaneous speech, are obligatorily possessed, we attribute this variation to analogy from the default possessed form of nouns, which take the indefinite possessor proclitic /a = /. Thus, /tama/ ‘tooth’ can be realized as [thaˈma] or [dhaˈma]. The alveolar plosive of the latter approximates its counterpart in [a = ddhaˈma] ‘someone's tooth’ (the equals sign ‘=’ represents a clitic boundary).Footnote 3

The plosives are generally not susceptible to changes in place – with the notable exception of the velar plosives. The lenis, voiced fortis, and fortis velar plosives are all backed, approaching a uvular-like articulation, when they are preceded or followed by /a/:

(3)

Affricates

The affricates, like the plosives, show a three-way contrast between lenis, voiced fortis, and fortis realizations. The lenis affricate often surfaces as a voiced alveolar fricative:

(4) kudzabi [khuˈʣabi] ~ [khuˈzabi] ‘brine fly pupae’

As shown in Figure 3, the lenis affricate contrasts with the voiced fortis and fortis affricates in both stop duration and fricative duration. But, again, as with the plosives, the voiced fortis and fortis affricates are distinguished by voicing.

Figure 3 Lenis affricates (closure duration: M = 15, SD = 22; fricative duration: M = 95, SD = 36) contrast with voiced fortis affricates (closure duration: M = 60, SD = 15; fricative duration: M = 76, SD = 18) and fortis affricates (closure duration: M = 100, SD = 14; fricative duration: M = 91, SD = 16) in both stop duration and fricative duration.

Nasals

While in more northerly dialects of Northern Paiute nasals show a three-way distinction in place – bilabial, alveolar, and velar – the Mono Lake variety only has a two-way distinction – bilabial and alveolar (northern dialect data from Liljeblad Reference Liljeblad1966):

(5)

Both bilabial and alveolar nasals show a distinction in nasal murmur duration, as shown in Figure 4. The lenis nasals are short, and the fortis nasals long.

Figure 4 Lenis and fortis nasals contrast in murmur duration.

Sibilants

Mono Lake Northern Paiute has a coronal fricative best-described as an alveolo-palatal sibilant, /ɕ/; see Babel (Reference Babel, Stanford and Preston2009: 37–42) for palatograms and discussion.Footnote 4 Like the nasals, the alveolo-palatal sibilant participates in a two-way lenis–fortis contrast. The lenis sibilant has a shorter fricative duration than the fortis sibilant, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 Lenis (〈s〉) and fortis (〈ss〉) sibilants contrast in fricative duration.

The sibilant has a palatalized allophone following /i/, characterized by higher laminal contact of the tongue surface and lip rounding:

(6)

As shown in Figure 6, the prominent spectral peak of the palatalized allophone (represented by the solid grey line) is around 4000 Hz, lower than that of the nonpalatalized allophone (represented by the solid black line), whose prominent peak lies around 6000 Hz.Footnote 5 The spectra in Figure 6 have been averaged across four tokens for each of the words in (6) above.

Figure 6 Prominent spectral peak of palatalized fricatives (grey line) is lower than that of unpalatalized fricatives (black line).

Vowels

Mono Lake Northern Paiute has six monophthongs, presented in Figure 7. Five of them – all except /e/ – exhibit a phonemic length contrast. After decribing the phonetic properties of the monophthongs, we turn to a discussion of potential diphthongs and the idiosyncractic vowel /e/.

Figure 7 Mono Lake Northern Paiute monophthongs.

Monophthongs

Formant values for the six monophthongs are presented in Figure 8, plotted logarithmically in two-dimensional F1-F2 space. Measurements were taken at the vowel midpoint and averaged across the consultant's productions recorded for the purposes of this illustration (N = 735). The long vowels occupy the periphery of the vowel space, having more extreme F1 and F2 values than the short vowels.

Figure 8 Mono Lake Northern Paiute monophthongs charted in two-dimensional F1-F2 space. (〈o〉 represents the low-mid back vowel /ɔ/, and 〈y〉 the high central vowel /ɨ/.)

All of the monophothongs except for /e/ exhibit a binary length distinction, as illustrated by the following near-minimal pairs:

(7)

Vowel durations were averaged across all tokens recorded for the sketch; long vowels averaged 193 ms (SD = 56), while short vowels averaged 131 ms (SD = 52). Since /e/ does not exhibit a length contrast, it is not illustrated above.

The vowel /e/

The vowel /e/ deserves special mention. Nichols (Reference Nichols1974: 38f.) claims that, while Northern Paiute has only five phonemic vowels, Mono, Kawaiisu, and all of Central Numic ‘have a sixth vowel contrasting with the five common to the other languages (see Map 3). This sixth vowel is usually written e, but in most of the languages the actual phonetic vowel varies among [a![]() ~ e

~ e![]() ~ e ~ ɛi]’. Most dialects of Northern Paiute do indeed lack this Numic ‘sixth vowel’, but the Mono Lake variety has it.Footnote 6 Like its counterparts elsewhere in Numic, it is variably realized as a monophthong, [e], or as a diphthong [

~ e ~ ɛi]’. Most dialects of Northern Paiute do indeed lack this Numic ‘sixth vowel’, but the Mono Lake variety has it.Footnote 6 Like its counterparts elsewhere in Numic, it is variably realized as a monophthong, [e], or as a diphthong [![]() ]:

]:

(8) ego [eˈɡɔ] ~ [

ˈɡɔ] ‘tongue’

ˈɡɔ] ‘tongue’

And, as Nichols observes (p. 42), the sixth vowel usually counts only as a single mora, which means that, when it occurs in a word-initial syllable, primary word stress falls on the second syllable, as in (8). The cognate forms in northern varieties of Northern Paiute has a high front vowel instead of the sixth vowel, e.g. Bannock [iɡɔ] ‘tongue’ (Liljeblad Reference Liljeblad1966: 75).Footnote 7 Nichols argues (pp. 38–50) that the sixth vowel must be reconstructed as a Proto-Numic diphthong /*![]() /, though see Babel et al. (to appear, Section 7.1) for a different historical analysis.

/, though see Babel et al. (to appear, Section 7.1) for a different historical analysis.

Word-level stress

In morphologically simplex words, primary stress falls predictably on the second mora. This means that when the first syllable of a word contains a long vowel, primary stress is word-initial, as in (9a). Otherwise, as in (9b), primary stress falls on the second syllable.

(9)

In Mono Lake Northern Paiute, stress is cued by pitch and vowel length. Vowels in stressed syllables are higher in pitch and have longer durations than equivalent vowels in unstressed syllables. This is shown in Figure 9, which plots the duration and fundamental frequency of stressed and unstressed syllables.

Figure 9 Stressed syllables (+) are higher in pitch and longer in duration than unstressed syllables (−).

One of Mono Lake Northern Paiute's most notable phonological features – devoicing – interacts with stress. Any vowel following a primary stressed syllable can be devoiced, though typically word-final vowels are affected. For instance, the last word of the penultimate sentence of the recorded passage below, /hanimaɡɡʷɨɕi/ ‘done making’, is realized as [haˈnimaɢɢʷɨɕ![]() ] with a devoiced vowel in the final syllable.

] with a devoiced vowel in the final syllable.

Transcription of a recorded passage

We present here a spontaneous procedural text, ‘Gathering willow and making baskets’, spoken by Madeline Stevens and translated by Grace Dick.

Community orthography

Yübano nümmi süügganna a nakabodomanekaasi. Suumi süüggabodonna yaisi oopiddunna. Yaisi dammi opiwünüpütuhu. Saa'a oka mamaggwüusi yaisi nümmi opomadabu'i. Yaisi tuadzu yaddatu. Tuadzu wonotu. Unika nümmi mada'e saa'a opiwünümma süübi hanimaggwüsi. Mihu sabbü yaisi nüü süübiggwetu waha.

Phonemic transcription

jɨbanɔ nɨmmi ɕɨːɡɡannaa = nakabɔdɔmanekaːɕi. ɕuːmi ɕɨːɡɡabɔdɔnna ˈjaiɕi ɔːpiddunna. ˈjaiɕidammi ɔpiwɨnɨpɨtuhu. ɕaːʔa ɔkamamaɡɡʷɨuɕi ˈjaiɕinɨmmi ɔpɔmadabuʔi. ˈjaiɕituaʣujaddatu. tuaʣuwɔnɔtu. unikanɨmmimadaʔe ɕaːʔa ɔpiwɨnɨmma ɕɨːbihanimaɡɡʷɨɕi. ˈmihu = ɕabbɨ ˈjaiɕinɨː ɕɨːbiɡɡʷetuwaha.

Phonetic transcription

jɨˈβanɔ nɨˈmmi ˈɕɨːɢɢannaa = naˈqhaβɔɾɔmaneqhaːɕ![]() . ˈɕuːmi ˈɕɨːɡɡaβɔɾɔnna ˈjeiɕi ˈɔːpiddhunn

. ˈɕuːmi ˈɕɨːɡɡaβɔɾɔnna ˈjeiɕi ˈɔːpiddhunn![]() . ˈjeiɕi ɾaˈmmi ɔˈphiwɨnɨphɨthuh

. ˈjeiɕi ɾaˈmmi ɔˈphiwɨnɨphɨthuh![]() . ˈɕaːʔa ɔˈqhamaˈmaɡɡwhɨuɕi ˈjeiɕinɨˈmmi ɔˈphɔmaɾabuʔi. ˈ

. ˈɕaːʔa ɔˈqhamaˈmaɡɡwhɨuɕi ˈjeiɕinɨˈmmi ɔˈphɔmaɾabuʔi. ˈ![]() eiɕ

eiɕ![]() thuˈa

thuˈa![]()

![]() jaˈddathu. thuˈa

jaˈddathu. thuˈa![]()

![]() wɔˈnɔthu. uˈniqhanɨˈmmimaˈɾaʔe ˈɕaːʔa ɔˈphiwɨnɨmma ˈɕɨːβihaˈnimaɡɡʷɨɕ

wɔˈnɔthu. uˈniqhanɨˈmmimaˈɾaʔe ˈɕaːʔa ɔˈphiwɨnɨmma ˈɕɨːβihaˈnimaɡɡʷɨɕ![]() . ˈmih

. ˈmih![]() = ɕabbhɨ ˈjeiɕ

= ɕabbhɨ ˈjeiɕ![]() ˈnɨː ˈɕɨːβiɡɡwheth

ˈnɨː ˈɕɨːβiɡɡwheth![]() waˈha.

waˈha.

Translation

In the autumn, we gather willows after they're done losing their leaves. At that time, we go around collecting willows, and then we clean the bark off them. We then make willow string. Later, after we finish that, we make round baskets. Or then, we make winnowing baskets. Or, we make burden baskets. We learn to make those kinds later with the willow string, after we're done gathering the willow. That's all I have to say about willows.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants at the 2008 Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas meeting in Anaheim who commented on our poster, as well as to Charles Chang, Andrew Garrett, and Tim Thornes for their suggestions. The comments of three reviewers and John Esling greatly improved the paper. We also thank Grace Dick, Leona Dick, Morris Jack, Elaine Lundy, Edith McCann, and Madeline Stevens for teaching us about their language. This research was supported by grants from the Sven and Astrid Liljeblad Endowment at the University of Nevada, Reno, and the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages at the University of California, Berkeley.