This is my final editorial. My first, in issue 41, 1 (March 2016), appraised Janelle Reinelt's championing of ‘internationalism’ as a paradigm for contemporary theatre scholarship. I recognized its conceptual and political value for a journal with the word ‘international’ in its title, but went on to assert that Reinelt overstated the continuing significance of the nation as a related frame. I was wrong.

At least, events since then have proved me so. So clamorous is the drumbeat of populist nationalism today, it is easy to forget how recently and rapidly it has taken hold at the centre of much global political discourse. In some places, such as Trump's America, Bolsonaro's Brazil, Duterte's Philippines and, albeit with differences, Brexit Britain, it has cemented a new and divisive political normal. In others, it has entrenched existing national chauvinisms and emboldened authoritarians to discredit opponents and dismantle democratic institutions. Elsewhere, the impacts have been more subtle, but nonetheless insidious. The ‘fake news’ canard has been deployed by numerous governments in ways that have more to do with avoiding journalistic scrutiny than with regulating incendiary falsehoods. In Australia, where I live, the developments are playing out at the day-to-day level in any number of different spheres. In late 2018, following an outcry over revelations that in 2017 the then minister for education vetoed $4 million of highly competitive, peer-reviewed research grants in the arts and humanities, claiming that taxpayers would not approve of the expenditure, his successor announced that all such grants will henceforth be subject to a ‘national interest test’. The fact that applicants and reviewers alike must already demonstrate value for money and national benefit would appear to be irrelevant; arguments for the intrinsic, international or multiple but hard-to-predict benefits of high-quality research were inaudible. In an environment already characterized by wilful inaction on climate change, hardline policies on asylum seekers and ill-conceived stunts such as spontaneously mooting the relocation of Australia's Israel embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, the fact-free disparagement of intellectual enquiry simply conformed to a familiar and increasingly baleful pattern.

So, yes, the ‘national interest’ is back, though it almost goes without saying that, where it is invoked, that phrase and its cognates promise neither to serve citizens fairly, nor to improve the international order of which nations are the constituent parts. To be sure, the causes of the current situation are complex and, to the extent they were borne of earlier distortions of nationhood and the depredations of globalization, understandable. Progressive responses need to be correspondingly multifaceted and creative – and the pages of an academic publication are in many ways far from the forefront of this struggle. Nevertheless, insofar as these recent developments offend some of the core values of this journal, there are at least two rules of thumb we might observe in understanding what we do, in relation to what has happened.

The first is to keep in view the full complexity and diversity of the phenomena that the terms ‘nation’ and ‘international’ describe: nations are multifarious in themselves, and vary widely in their composition, rendering the international a dynamic and uneven domain. It was with this in mind that I revisited the nine issues of TRI that have appeared since my first editorial, whose sustained diversity illustrates the international commitment both to those values on the part of writers in our field, and indeed to internationalism as one such value. Of the forty-six articles or equivalent to have been published, thirty different nations or territories have been represented, with 75 per cent of the pieces requiring multilingual competence on the part of the authors.Footnote 1 Approximately half of the contributors have been located outside Europe and America, and a little over two-thirds of the research has focused on non-Euro-American sites. To be sure, there remains some unevenness in coverage: of that two-thirds, East, South and South East Asia are well represented (fifteen articles); other areas, including the Middle East (five), Africa (five), South America (four) and Oceania (four), less so. Digging deeper into the figures reveals further imbalances and complications. For example, three of the Africa articles are on South Africa, and there have been no articles on the Pacific. On the other hand, while proportionately more researchers are US- and Europe-based, by nationality they are highly cosmopolitan and globally mobile. The relatively small number of American contributions, meanwhile, are amongst the most explicitly internationalist in scope – though even that metric is further complicated by articles on refugees, online archives and interplanetary performance.

There is no room for complacency. The bulk of published scholarship in the journal continues to be produced in those places with the greatest investment in research-intensive universities, and where there tends to be a cultural, historical or institutional anglophone advantage. But the content of the journal also testifies to the fact that this landscape is changing rapidly. TRI is doing well at remaining abreast of these changes, but there is always more to be done to get upstream of that, to drive those changes as much as reflect them, at least within the discipline of theatre studies, and in response to contemporary theatre practices.

The second value we might bring to bear in light of recent global developments is knowing where and how to look, and what to disregard. Theatrical stunts, media spectacles and highly effective political trolling have been integral to the rise of populist nationalism. It is tempting for those of us professionally responsive to aesthetic and political innovations, of whatever stripe, to go chasing after each new revelation or provocation. Some do indeed demand sustained critical attention. But in other cases, the harder challenge is to avoid taking the bait, and instead look elsewhere, registering or indeed bringing to light what is hidden, latent or actively obscured.

The articles in this issue represent a thoroughly international range of perspectives on performance that each, in their own way, directs our attention towards what is important, and asks us to think anew about what we find there. Emma Willis's ‘Acting in the Real World’ presents a distinctive take on a current issue: accusations and revelations of sustained sexual misconduct in the acting industry – mainly towards women – that have coalesced around the #MeToo and Time's Up movements. Taking as her starting point the case of New Zealand actor and teacher Rene Naufahu, who responded to accusations of sexual assault in his acting classroom with the claim that he was training students for the ‘real world of acting’, Willis unfolds an enquiry into the ways in which ‘the method’ has long enabled iniquitous, if not abusive, practices. Of particular interest is how the rhetoric of the method distributes the power to determine what is ‘real’ unevenly across the nexus of actor, director and teacher relations, masking exploitation with invocations of actorly truth on the one hand, and the realities of a highly competitive industry on the other.

Willis's analysis importantly serves to contextualize recent developments both historically and in relation to lay understandings of acting and the public persona of the actor. In so doing, her article inaugurates several strands of enquiry concerning performance, power and the body that extend across the other articles in the issue. Chen Ya-Ping's ‘Shen-ti Wen-hua’, which she translates from the Mandarin as ‘culture of the body’, offers a patient and lucid account of the fortunes of the body in Taiwan as it was shaped by a succession of political and ideological regimes over the course of the twentieth century, and mobilized in response by performance artists and theatre-makers. The Japanese Empire, the dictatorial government of the Nationalists who fled the Chinese mainland in 1949, and, following the collapse of authoritarianism in the 1980s, the embrace of multinational capitalism, have all left their mark on how Taiwanese bodies have been thematized and disciplined. Against this background, Chen highlights a number of key performances from the 1980s onwards whose treatment of the body has moved in nuanced relation to these dominant trends: from direct political resistance, through the diversification of corporeal identities, to an enquiry into the cultural and spiritual sources of a new Taiwanese identity that relates in complex ways to the consumer society of the 1990s and beyond. Accordingly, Chen tells a story that is at once familiar from any number of locations over the course of the last century, and at the same time highly specific in its cultural configurations, as well, as the title suggests, as in the concepts and terminologies that have been used to interpret it.

María Estrada-Fuentes's ‘Performative Reintegration’ picks up several of the historical concerns of Chen's article, and returns us to the present day. The basic question Estrada-Fuentes asks is how theatre can be used as a way of managing post-conflict processes through the attention it affords embodied practices and relations. The focus is contemporary Colombia, which is currently working to integrate former combatants from a long and bloody civil war. It is tempting to write ‘integrate into mainstream society’, but Estrada-Fuentes's point is that successful integration is a two-way process: as former combatants adapt to civilian life, so must society, or at least those parts with which they interface most directly, respond in kind, changing to reflect the new entity it has now become. While theatre has been used extensively as a means for ex-combatants to represent their experiences, Estrada-Fuentes was interested in exploring whether theatre might be more subtly and perhaps durably beneficial if focused more on process. She goes on to describe a series of workshops conducted with ‘reintegration tutors’ – case workers for the ex-combatants. Estrada-Fuentes is honest about some of the obstacles she encountered in seeking to implement the project, but also illuminating on how the workshops prompted self-reflection on the part of the tutors, and increased sensitivity towards the often tacit dimensions of reintegration, informed by corporeal biographies that are complex and fraught, and require careful treatment as they are adapted to civilian functions.

Faisal Adel Hamadah's ‘Travelling Theatre’ revisits the broad sweep of twentieth-century developments traced by Chen in Taiwan, but from the opposite side of the Asian continent. While Syrian playwright and intellectual Saadallah Wannous (1941–97) is well known and well regarded, notes Hamadah, this renown tends to be concentrated in a number of separate and often localized domains. Hamadah therefore undertakes to provide a basis on which Wannous's achievements might be more widely recognized. He does so by outlining the international sensibility underpinning what has otherwise come to be seen as Wannous's specific contributions to Arabic theatre. To begin with, Hamadah considers in some detail the formative role Wannous's soujourn in Paris during the tumultuous years of the late 1960s had upon the development of his ideas. Interacting with many of the most significant francophone theatre-makers of the time, argues Hamadah, suggests that Wannous's subsequent work be considered in relation to post-colonial internationalism, even as he grew in stature as an artist and thinker upon his return to Syria. Instead of focusing on Wannous's well-known plays, Hamadah considers his translations of European plays, particularly that of a relatively little-known Peter Weiss play, Wie dem Herrn Mockinpott das Leiden ausgetrieben wird (How Mister Mockinpott was Cured of His Sufferings) (1968). First staged in 1978, Wannous's translation has gone on to be staged with startling regularity – far more so than Weiss's original, and especially during and following the Arab Spring. By placing Wannous's internationalism at the centre of his achievements, argues Hamadah, we gain not only a new perspective on a signal figure of Arab theatre, but also a means of thinking differently about the international theatre landscape: one including Wannous's ideas and innovations.

Bryan Schmidt's ‘Fault Lines, Racial and Aesthetic’ rounds out the issue by bringing us back to the contemporary moment, and the fate of localized cultural production within a globally informed discursive framework. He focuses on the National Arts Festival in South Africa, a major annual event that is integral to the prosperity and reputation of the small host town, whose name was changed from the colonial-era Grahamstown to Makhanda in mid-2018. That change is a piquant reminder of how history and place intertwine, and in his article Schmidt focuses on the ways the intensive place-making that the festival enacts reproduces many of the dynamics and divisions of race and class that have marked South Africa's past and continue to shape its present. Schmidt demonstrates how comprehensively the festival has come to be understood and evaluated according to the discourse and metrics of the creative economy, and argues for an aesthetic approach to the event: one that can disclose its informal and affective registers. Doing so, argues Schmidt, sensitizes us to the lived experience of participants – mainly black South Africans – whose commercial and creative labour contributes substantially to the ‘vibe’ of the festival, but which remains constantly vulnerable to the policing and zoning of the town in ways that significantly complicate the stories the festival tells about itself.

Schmidt's is the final article in this issue. We begin, however, with some remembrances of Egyptian theatre scholar Hazem Azmy (1967–2018), who passed away suddenly during the annual conference of the International Federation for Theatre Research (IFTR), with which this journal is affiliated, in Belgrade in July 2018. As the astute, touching and wide-ranging recollections gathered here attest, Hazem's achievements ran the gamut from the intellectual to the institutional, always accompanied by a dose of immense personal charm. Amongst numerous other achievements, in 2013 Hazem co-edited a special issue of TRI with Marvin Carlson on Theatre and the Arab Spring (38, 2). Many readers of this journal no doubt also have personal memories of Hazem, who was an integral member of the IFTR community. I first encountered him when delivering a seminar paper at Warwick University, where he was a wry PhD student with a twinkle in his eye and an unexpectedly warm smile. We chatted periodically thereafter, and it was to find out what Hazem had been thinking about recently that I attended the panel he was due to present on in Belgrade. His absence was a puzzle to everyone, including his co-panelists. Perhaps having spent time anticipating his arrival and conjuring his spirit in lieu during the session, learning the following day of his death likely hit all of us who had been in that room with uncanny force. The greater shock, of course, was for his many dear friends and collaborators in the IFTR Arabic Theatre Working Group and beyond, some of whom are represented in these pages. I am very grateful to Nora Amin, Marvin Carlson, Margaret Litvin, Mustafa Riad and Iman Ezzeldin for their accounts of Hazem's life and achievements, and to Sarah Youssef and Katherine Hennessey for their assistance and advice. A bursary award to support student attendance at the annual IFTR conference has been set up in Hazem's name, and you can donate at https://gogetfunding.com/hazem-azmy-iftr-bursary-award-fund.

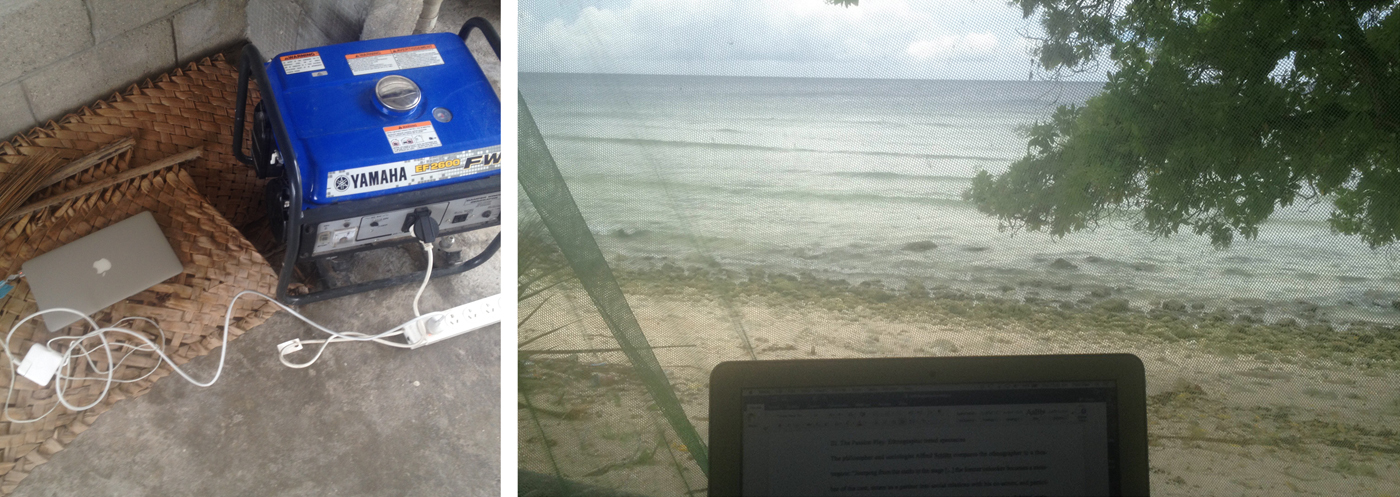

The outpouring of grief and appreciation that has followed Hazem's passing in this journal and elsewhere underscores not only the importance we attach to many of our peers, collaborators and interlocutors, but also how poor we often are at acknowledging it when in the thick of scholarly activity. In drawing this editorial to a close, this compels me only to redouble the thanks I owe those individuals who have made my editorship such a constant and humbling source of delight. I have been truly inspired by the patience and commitment shown by all of the individual authors whose articles have featured in the past nine issues. Their ability to balance an impassioned engagement with their material and a willingness to sustain detailed attention to the nitty-gritty of the text over an often punishing drafting process is one of the hidden strengths of our discipline, and I thank them for revealing it to me. Similarly, the many anonymous peer reviewers I have called upon in order to help maintain the high intellectual standard of the journal acted selflessly, graciously and promptly, and taught me a great deal in the process. The editorial board – for reasons of space, I direct you to the front matter of the journal for the roll of honour – have been an invaluable source of support and insight. The same goes for the IFTR Executive Committee, especially president Jean Graham-Jones, and vice president Elaine Aston, who I knew I could rely on absolutely for astute advice and all-purpose wisdom, invariably on a lightning-fast turnaround. Holly Buttimore, commissioning editor of humanities journals at Cambridge University Press, has always paired effortless reliability and engagement with great good humour, and Paul Hague showed great professionalism and forbearance as production editor, before being ably replaced by Keira Keep. It is a lucky curse that the international remit of the journal has intertwined with my own personal and professional travels. I have sometimes thought I should maintain a Tumblr account documenting the many places this journal has been edited (Fig. 1): what that would leave out would be the stoic faces of my long-suffering family – Kaylene, Lo, Sum – as I sang out that I was ‘almost finished’ with a last paragraph or final email. I cannot thank them enough for their patience.

FIG. 1. (Colour online) TRI brought to you by generator from (amongst other locations) a buia (sleeping platform) on the Pacific island of Marakei, Republic of Kiribati.

Like peer reviewing, book reviewing is another of those time-consuming activities that tends to receive little, if any, recognition from universities that, congenitally insecure about their place in the global pecking order, nevertheless require well-reviewed publications to reassure them of the quality of the employees beavering away under their very noses. Senior reviews editor Margherita Laera worked with Mary Caulfield, Meg Mumford and latterly Charlene Rajendran to produce an invaluable resource not only for the profession, but also the discipline (the difference being subtle but significant). Along with the many individual book reviewers, they have ensured that a properly international picture of scholarly theatre publishing is possible. Caoimhe Mader McGuinness has seamlessly taken on Margherita's role, while Fintan Walsh, of Birkbeck University of London, now takes on the senior editorship of TRI. Fintan has been a fantastic associate editor; I owe him a huge debt. He is unflappable, with an unerring eye for what works in an article, and a keen sense of how to address what doesn't. Fintan will be joined by new associate editor Silvija Jestrovic, from the University of Warwick. In her extensive meditations on theatre and exile, informed by her own life experiences, Silvija brings a distinct sensibility that can only nuance the ways in which the journal performs its mission. Finally, special thanks to my friend and colleague, assistant editor Sarah Balkin. All the best things about how this journal has functioned are down to Sarah. The writer of every article has been on the receiving end of her patient but forensic quizzing on everything from page numbers to phrasing to the flow of an argument and the basis for a claim. And I have benefited hugely, not only from her sound judgement on major decisions, but also from the opportunity to maintain a running dialogue on the granular details of the content, which is really where the integrity of the journal stands or falls.

All the strengths of the last nine issues can be traced to these individuals. And what are those strengths? Scholarly expertise and rigorous, ethical research; agreed standards of evidence and persuasive argumentation; the sustaining of productive and respectful debate; writerly refinement and editorial scrupulousness; peer review; proofreading and copy-editing. These should be truisms of academic knowledge production. Remarkably, however, we find ourselves needing actively to assert and affirm them as values worth holding onto in a political environment that ingeniously but rashly joins easy impulse with blind atavism, floating a procession of quick fixes to complex and enduring problems that can only render meaningful solutions harder and more remote.

Yes, dear reader, it has come to this: we find ourselves looking again at the bread and butter of academic work, and discovering in it something approaching a moral purpose. This says more about the pass to which some societies have come than about any inherent virtue on our part. Indeed, the risk of hubris is ever-present. Our work is conventionally local and specific, or distributed over a wide but very slender network of readers and respondents. But there is also a cumulative effect and indeed an institutional heft to those efforts. It manifests in long-standing publications such as this one, testifying to values that are increasingly under threat in the environments where many of us live and work, and providing a small but durable resource for the cultivation of ideas about theatre that might pass the international interest test.