INTRODUCTION

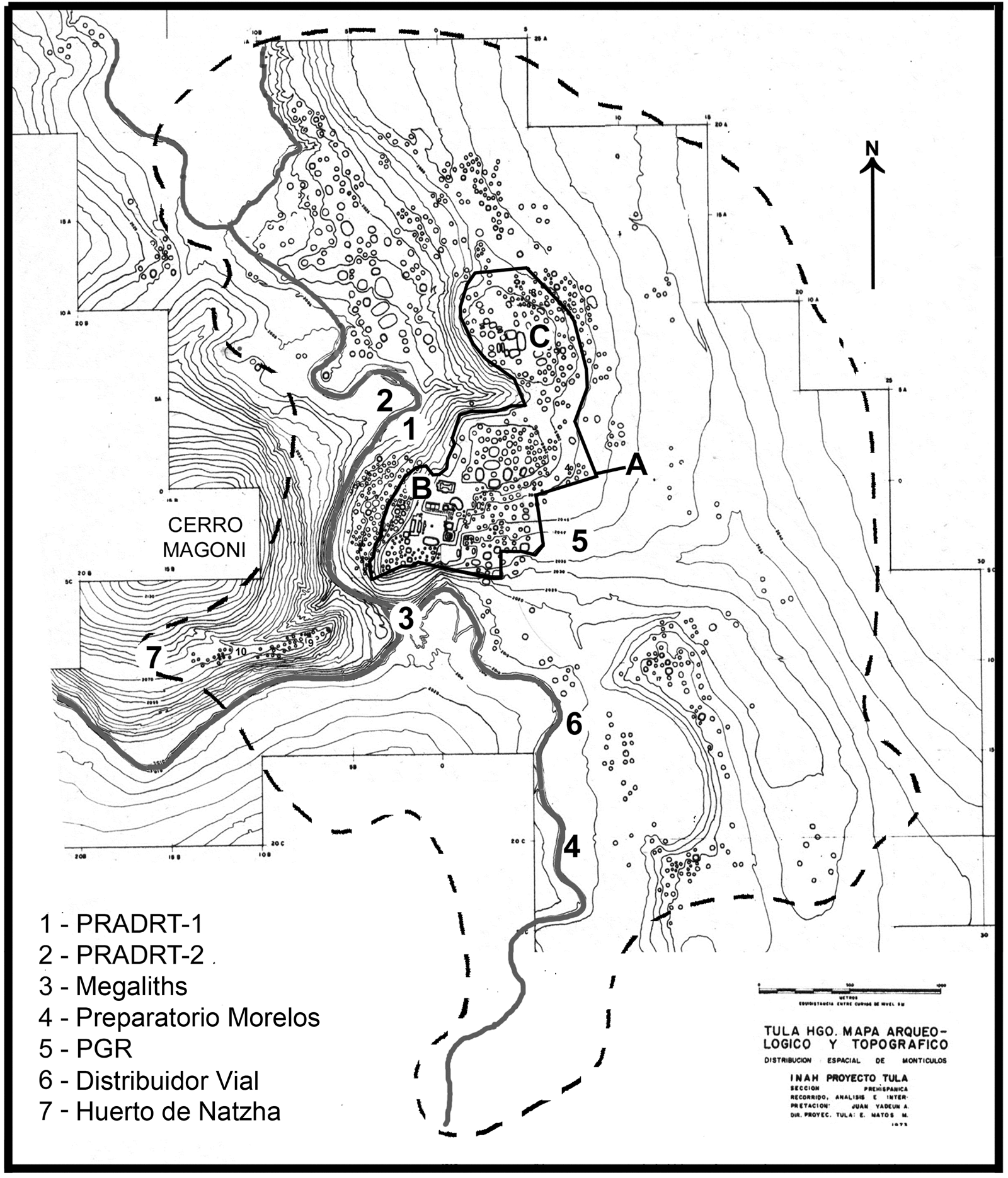

For around the first 800 years following its demise, the ruins of ancient Tula remained relatively intact. During his pioneering investigations at Tula Grande in the 1940s and 1950s, Jorge Acosta encountered remarkably undisturbed archaeological remains that permitted detailed reconstructions of Tula's administrative sector. As recently as the early 1970s, excavation in other parts of the ancient city encountered intact walls and stucco floors as little as 10 cm below the surface, a reflection of farming largely with animal-drawn plows. At that time, abundant sherds, building stone, and other prehispanic occupation debris littered the site surface and provided a means of delineating Tula's limits, currently estimated to cover an area of approximately 16 square kilometers, which, in the early 1970s, was a lightly populated, diverse landscape of river valleys, hills, and plains, with Tula de Allende, a modern town of a few thousand inhabitants, at its center (Figure 1). Ceramics recovered from survey and excavation established an eight-phase ceramic chronology spanning the Late Classic/Epiclassic through Late Postclassic/Colonial periods (Table 1).

Figure 1. Topographic map of Tula (from Yadeun Reference Yadeun and Moctezuma1974) showing the estimated urban limits (dashed line), the protected archaeological zone (a), the Tula Grande (b) and Tula Chico (c) monumental centers, and the seven localities described in the legend.

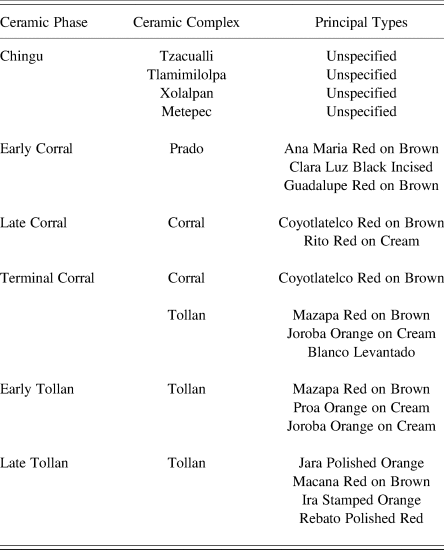

Table 1. Revised chronology for Tula and the Tula region (after Healan et al. Reference Healan, H. Cobean and Bowsher2021).

Since the mid-1970s, however, the landscape has changed considerably, with the arrival of mechanized agriculture, industrial and related development on a grand scale, including construction of one of the country's largest oil refineries, along with petrochemical and thermoelectric plants, construction of a major highway network, and the meteoric growth of Tula de Allende and neighboring towns with the influx of workers, all of which wreaked considerable havoc on the ancient city and continues to do so. Fortunately, in 1983, an official protected area was established (Figure 1a) that has preserved a 1.1 km2 portion of the heart of the ancient city, including the monumental centers of Tula Grande and Tula Chico (Figures 1b and 1c).

While it is indeed gratifying that Tula's ritual and administrative core is preserved for posterity, the rest of the city remains unprotected and at risk for what will almost certainly be near complete destruction. It is, of course, unrealistic to expect to protect the remains of a whole prehispanic city, although other options exist. Recently, the area occupied by the ancient city was subdivided into three zones, with differing degrees of allowable modern modification; but in all three, some degree of archaeological intervention is required before land can be modified. In accordance with this new requirement in his capacity as director-in-charge of the Tula Archaeological Zone, Gamboa Cabezas has conducted archaeological salvage projects over the past decade in well over 100 different localities within the ancient city, outside the official protected area. In most cases, archaeological intervention involved excavation of several 2 × 2 m exploratory pits. Prehispanic ceramics and other artifacts were recovered from excavation in virtually all localities, and walls, floors, and other structural remains were encountered in about half of the localities where excavations were conducted. In nine localities, archaeological intervention included more extensive exposure of structural remains in light of features of interest encountered during exploratory excavation. Six of these localities produced discoveries that have significantly augmented and in some cases transformed our understanding of ancient Tula, and are the subject of this article, along with another discovery that came to light during recent construction activity.

These excavations provided the opportunity to open small windows on six different neighborhoods at scattered locations within the ancient city (Figure 1), including several in peripheral locations at or near the urban limits. In most, if not all, of the six localities the excavated remains included what are almost certainly residential structures, exhibiting an architectural and material diversity that suggests a notable range in status of occupants at the neighborhood level, including individuals of seemingly high status who appear to have been a component of neighborhoods throughout the city rather than being concentrated at its core. Other revelations include widespread evidence of ritual activity associated with both termination of previous structures and dedication or consecration of new construction, leaving evidence of mass sacrifice and some of the most sensational objects found to date at Tula.

Before continuing, it is necessary that the reader understands that the investigations described below were salvage and rescue operations, often undertaken under severe temporal constraints and occasionally in hostile work environments, with limited personnel and resources for both field and laboratory. Much of the material recovered is still in the process of being analyzed, which makes the opportunity to present these largely preliminary findings of particular importance.

PROYECTO RESCATE ARQUEOLÓGICO DRENADO DEL RÍO TULA (PRADRT)

In 2017 the Federal Government, under the auspices of the Consejo Nacional de Agua, initiated a project to canalize a 19.2 km stretch of the Tula River and construct a highway alongside the canalized river. Since this includes the portion that flows through the site, an archaeological rescue project was initiated for that portion of the prehispanic city bordering the river. The first of what are anticipated to be several field seasons was conducted in 2018 at two localities, designated PRADRT-1 and PRADRT-2, situated in an area where the canalization project was already under way (Figure 1). Excavations in both localities produced evidence of dense prehispanic occupation, including several highly unusual finds of considerable interest.

PRADRT-1

The PRADRT-1 locality is situated along the east bank of the Tula River, between Cerro Magoni and Cerro El Tesoro, where Tula Grande is located (Figures 1 and 2). At the time of the intervention, the locality was being used as a waste dumping site for the river canalization project, which included the excavation of two large pits to hold construction waste. Preliminary reconnaissance identified ceramics and architectural stone on the surface and stucco floors exposed in the pit walls that indicated prehispanic structures. A 2 × 2 m grid was imposed over a block of land of approximately 30 × 30 meters, between the river and the adjacent terrace. In addition, a series of exploratory pits were excavated at various points, several of which were subsequently expanded to explore features of interest (Figure 2). Although somewhat discontinuous, the excavations exposed a discernible pattern of remains that represent structures and other features. Given limitations of time, excavation generally proceeded only to the first intact remains, which were consistently associated with Tollan phase ceramics, although one area excavated to tepetate, the caliche layer that is essentially the “bedrock” in the region, yielded Terminal Corral phase ceramics in the lowest levels (Tables 2 and 3).

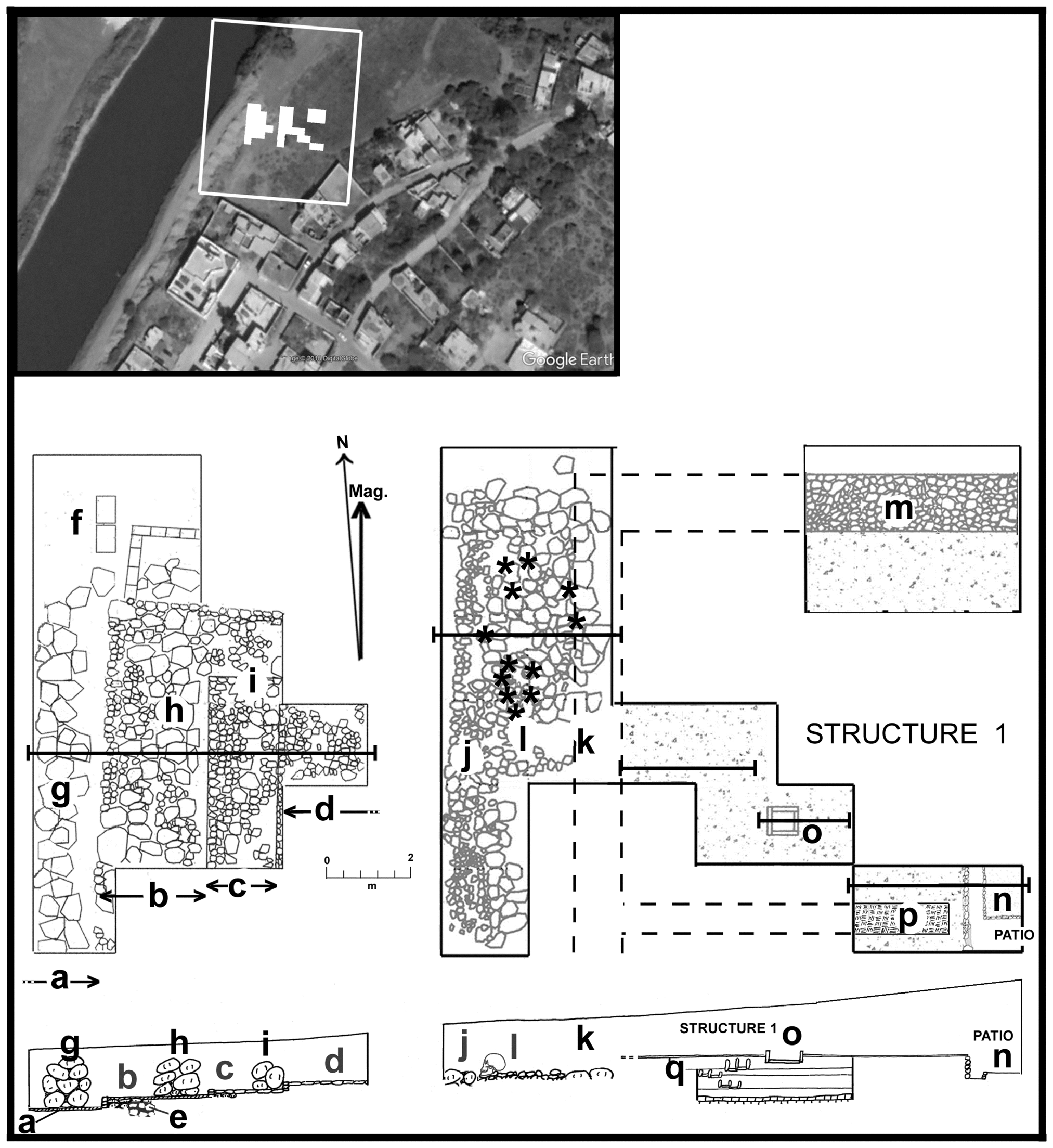

Figure 2. Map of the PRADRT-1 locality and the excavation areas. Letters refer to features discussed in the text. Asterisks indicate location of human skulls shown in Figure 3. Google Earth imagery; plan design by Healan.

Table 2. Ceramic phases, corresponding ceramic complexes, and principal types in the Tula ceramic chronology (Cobean Reference Cobean1978).

Table 3. Evidence of occupation by phase.

Excavations at the west end of the grid encountered a complex system of structural remains representing what appear to be three different episodes of prehispanic construction. The second of the three episodes involved construction of four low platforms that formed a series of step-like features paralleling the terrace (Figures 2a–2d). Platform B overlies a wall remnant (Figure 2e) representing the earliest of the three discernible construction episodes. Platforms B and C each measured approximately 2 meters in width, as did the exposed portions of platforms A and D. Each platform was constructed of stone, with a veneer of small tabular stone along its west edge, a common decorative facade in Tula, and the upper surface was paved with flat stones. Platform A was floored with stucco. Excavation at the north end of platform A encountered two rectangular adobe-lined pits, each approximately 1 meter in depth (Figure 2f). Both pits were covered with adobe blocks, but neither contained any visible remains except for one piece of undefined, possibly carbonate, material.

The last of the three episodes involved the construction of three large stone walls atop platforms A, B, and C (Figures 2g–i), which appear to have been part of a system of cajones, referring to a grid of intersecting walls whose interstices were filled with soil and rock, a type of foundation often used at Tula to support large structures. Only the lowest courses of the three walls and some of the intervening fill remained intact, probably a result of erosion given the relatively thin soil cover and the proximity of the river. These would appear to be the remains of a large platform that has been largely destroyed.

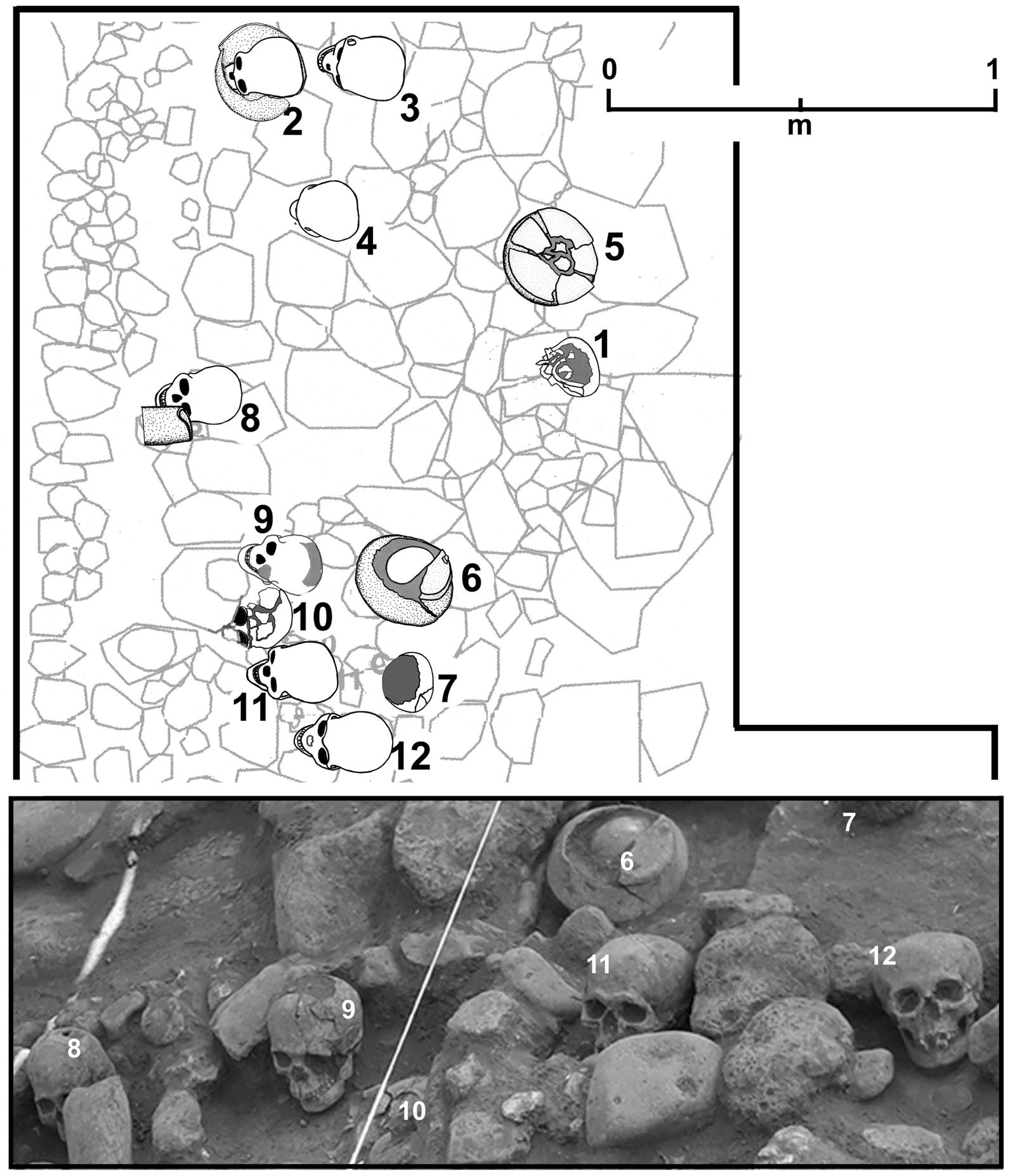

Excavations immediately to the east encountered two parallel north–south walls (Figures 2j and 2k), both badly damaged, and an intervening concentration of loose stone (Figure 2l). Wall J coincides with the edge of a terrace, hence is probably a retaining wall, while wall K appears to be the west exterior wall of Structure 1, immediately to the east. One of the most notable finds in the PRADRT-1 locality was the discovery of 12 human skulls, including mandibles (Figure 3) on top of the loose stone concentration between the two walls. All 12 faced west, including three that were placed in shallow ceramic vessels, two of which were covered, in turn, by other vessels. All appear to be adults, and informal examination revealed cut marks on some crania and mandibles, indicative of defleshing.

Figure 3. Detail of human skulls encountered in PRADRT-1 locality. Photograph by Gamboa Cabezas, drawing by Healan.

This mass display of human crania is reminiscent of the tzompantli or skull racks that have been found at various sites in Mesoamerica, including Tula Grande. However, this particular feature exhibits several notable differences, including the presence of articulated mandibles, the absence of impalement damage, and the use of ceramic vessels as containers in some cases. Based on unpublished field notes, Elson and Mowbray (Reference Elson and Mowbray2005) noted that Vaillant encountered a similar practice of placing human skulls in vessels at Las Palmas, an Early Postclassic occupation on the ruins of Middle Classic Teotihuacan, which he called “skull burials,” a name that implies interments rather than displays.

Unlike skull racks, this feature appears to have been a one-time event, involving the placement of 12 skulls on a pile of loose stone between the terrace wall and the rear wall of Structure 1. If the stone were rubble from the adjacent walls, their placement would have occurred at the end of the prehispanic occupation of the locality, and may bespeak violence that accompanied Tula's demise. One would wonder, however, how these 12 skulls managed to remain undisturbed until they were uncovered in excavation. A more likely explanation is that the loose rock on which the skulls were placed was not building rubble but fill—that is, a continuation of the system of cajones immediately to the west—and hence appears to have been a dedicatory offering that was initiated during construction. Evidence of other apparent pre-construction dedicatory ritual, in this case involving the mass sacrifice of a number of children, was encountered in the Procuraduría General de la República locality excavations, described below.

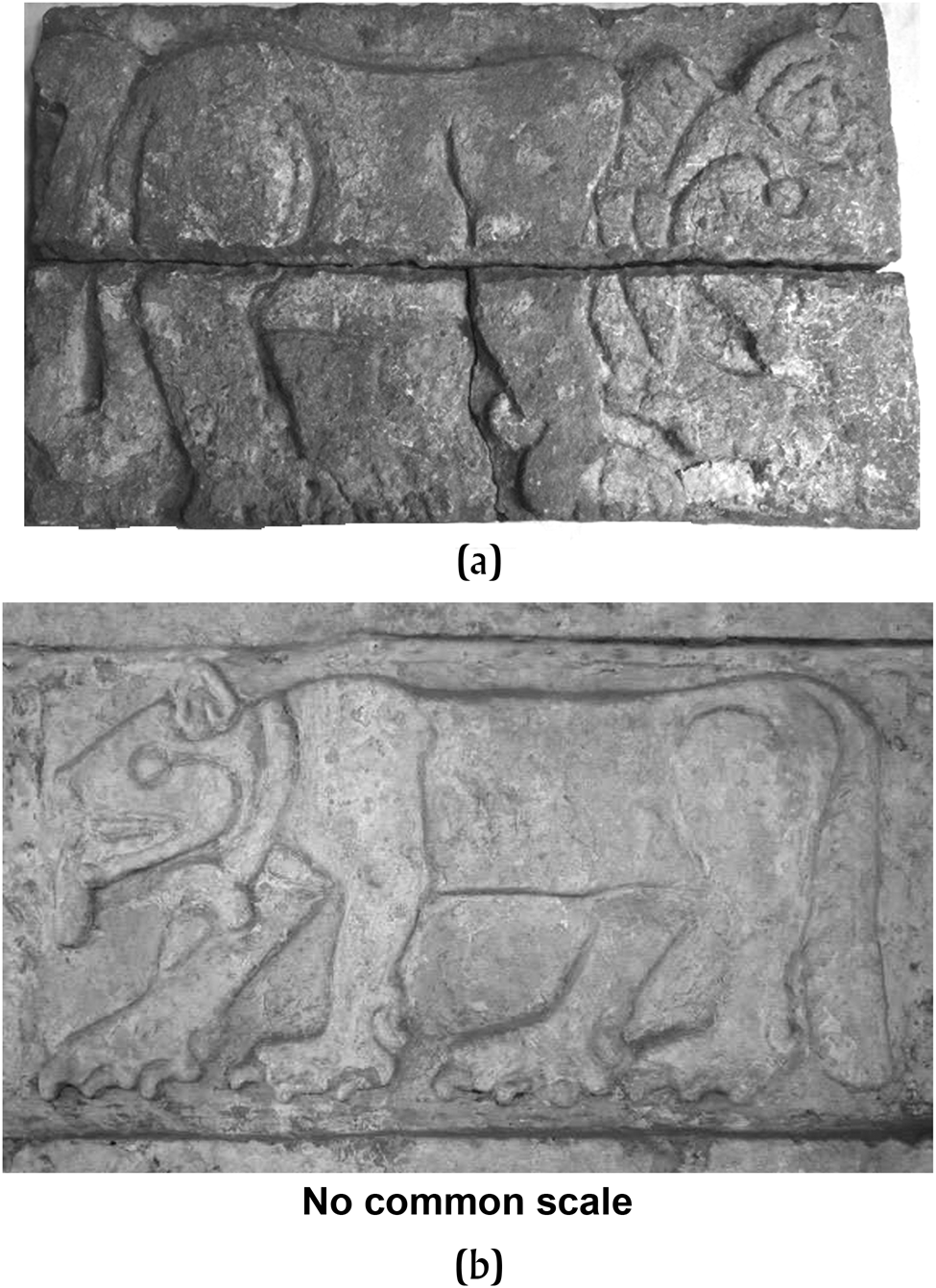

Excavation immediately to the east encountered the northeast portion of what was apparently a very large building, designated Structure 1 (Figure 2). Its southern and eastern limits lay outside the area excavated, but its north exterior wall was a well-constructed stone wall over 1 m thick (Figure 2m), and its west exterior wall was the remains of wall K. Only the northwest corner of the building was exposed, including a spacious room on the western and northern sides of an interior patio containing an altar (Figure 2n). The room was bounded on its south side by an equally wide (0.8 m) adobe wall (Figure 2p), its floor and walls were covered with stucco, and it contained a large (0.8 m wide) tlecuil (Figure 2o), constructed of two carved stone panels that had been carefully broken in half and placed so that the sides with the images faced outward, although they lay below floor level. One is a panel depicting a jaguar in motion (Figure 4a). The other (not shown) is an image of what appears to be the head of an eagle with volutes (Elizabeth Jiménez García, personal communication) and a series of circular symbols or chalchihuitls, a common iconographic element at Tula.

Figure 4. Feline representations from PRADRT-1 locality and Tula Grande. (a) Carved slab from tlecuil in Structure 1, PRADRT-1 locality; (b) tablero from Pyramid B, Tula Grande. Note similar collars and strikingly similar head features. Photographs by Gamboa Cabezas.

The jaguar panel is quite similar to those that form a procession on the facade of Pyramid B at Tula Grande (Figure 4b), although the two proceed in opposite directions. Nevertheless they are so similar in form that the PRADRT-1 specimen may have come from another facade of Pyramid B or some other structure at Tula Grande. Other sculpture strikingly similar to specimens from Pyramid B or elsewhere at Tula Grande were encountered in excavations at the Zapata II locality, approximately 0.5 kilometers to the south of the PRADRT-1 locality, including panels depicting jaguars and eagles devouring human hearts (Paredes Gudiño and Healan Reference Paredes Gudiño and Healan2021:Figure 8b).

Exploratory excavation beneath the floor of Structure 1 encountered nearly 1 m of soil and interbedded compacted earth strata overlying tepetate, rather than a continuation of the platform and cajones encountered immediately to the east; hence Structure 1 appears to have been constructed atop the river terrace which the platform abutted. While no walls or other hard architectural features were encountered beneath Structure 1, excavation encountered three superposed enigmatic receptacles, each resembling two conjoined tlecuiles (Figure 2q), although narrower and deeper and constructed of unworked stone that gave them a rather crude appearance. Two contained ashy soil and evidence of exposure to fire. Thus it appears that Structure 1 was erected on previously open terrain that had been the site of regular activity involving an unusual feature that held fire and was rebuilt over time.

Judging from the immense north wall and spacious interior, Structure 1 is clearly a very large building. If it were a residence, its size and apparent layout, which includes a large room or rooms surrounding an interior patio, suggest it was an elite residence comparable to Edificio 4 at Tula Grande, which may have functioned as a palace (Báez Urincho Reference Báez Urincho2021). The entire corpus of remains encountered in the PRADRT-1 locality were probably part of a single, integrated construction activity along the edge of the river that included the large platform that abutted the adjacent terrace and Structure 1. Additional structures may have existed atop the platform, but only its base remained.

The processing of human skeletal material, specifically crania, may have been an important activity in the PRADRT-1 locality, based not only on the 12 skulls that may have been a dedicatory offering, but also on the recovery of two other human mandibles and a ceramic vessel containing a human skull and finger bones in several of the initial exploratory pits. The general lack of postcranial material—hence a focus on crania—may represent preparation activity associated with the tzompantli at nearby Tula Grande.

PRADRT-2

The PRADRT-2 locality is located across the river from and slightly north of PRADRT-1 (Figure 1). The area of investigation was adjacent to an access road that had been built for the river canalization project, and excavations were focused on an area along the edge of the roadway, approximately 30 × 30 meters (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Map of the PRADRT-2 locality, showing small, stone-lined platforms (A–J) discussed in the text. Note construction activity along sides of river in photograph. Google Earth Imagery; plan drawing by Gamboa Cabezas and Healan.

All four exploratory excavations initiated within the locality encountered structural remains almost immediately, and were expanded to reveal seven low (approximately 30 centimeters tall), nearly square platforms, measuring 2–2.5 m in width (Figures 5a–5g), exhibiting a common, closely spaced, grid-like orientation. Each platform consisted of stone retaining walls surrounding a fill of soil and loose stone. The upper surface was unpaved, with no evidence of surmounting structures. All seven platforms rested on a stucco floor.

Associated artifacts included a large quantity of rhyolite debitage, a volcanic stone that occurs naturally on nearby Cerro Magoni; hence the manufacture of rhyolite implements or other artifacts appears to have been a major activity in the locality.

Excavation beneath the stucco floor in a narrow transect at the north end of the excavation encountered a thick layer (approximately 1.5 meters), containing what appears to be refuse from a ceramic figurine production facility, described below, which overlay a second stucco floor, beneath which were encountered portions of three partially exposed platforms of the same general size and form as the overlying platforms, but with a different orientation and a stuccoed surface (Figures 5h–5j). These three platforms were constructed over a thin soil layer overlying tepetate, and were associated with Terminal Corral complex ceramics (Tables 2 and 3).

These platforms, and their closely spaced, grid-like configuration, are unlike anything previously encountered at Tula, invoking images of the “Merchant's Barrio” at Teotihuacan, whose inhabitants lived in small, perishable circular structures, unlike the massive rectangular apartment compounds typical of the rest of the city. Unlike the latter, whose ceramics were typical of the Gulf Coast, those associated with the PRADRT-2 platforms are local (Terminal Corral and Tollan complex) ceramics, and the structures appear too small and too closely spaced to have been used as dwellings. A more likely possibility is a storage function, perhaps supporting perishable bins or other structures comparable to the recently discovered cuexcomates, or corn bins, at the Late Formative village site of Tetimpa, Puebla (Plunket and Uruñuela Reference Plunket and Uruñuela2018).

In total, 2,425 mostly fragmentary specimens of ceramic human and animal figurines, along with perforated disks and fragments of figurine molds, were recovered from the intervening fill (Figure 6). In addition to molds, the figurine specimens included overfired items, specimens broken during firing, and other wasters commonly associated with ceramic production facilities. Human female figurines exhibit a range of patterns of dress, hair, and head treatment (Figure 6a), while male figurines likewise exhibit a variety of accoutrements and body poses (Figure 6b), including helmets and hand-held objects suggestive of arms. Some males wear what appear to be human body parts or human skin, the latter associated with the deity the Aztecs called Xipe Totec. Many specimens exhibit combinations of red, blue, and black paint, the latter probably asphaltum. Fragments of animal heads and perforated disks (Figure 6c) suggest the workshop was also engaged in the production of wheeled animal figurines, a common artifact at Tula and other sites in Mesoamerica. We assume the workshop where this refuse was produced was located nearby. The refuse included numerous pottery sherds, lithic artifacts, worked and unworked animal bone, including needles, and other common household debris, suggesting the associated material was derived from a facility where figurine crafters both lived and worked, consistent with the conventional definition of a craft workshop.

Figure 6. Examples of objects recovered from probable figurine workshop midden used as platform fill, PRADRT-2 locality. (a) Whole female human figurines; (b) whole male human figurines; (c) animal figurine head and ceramic wheels. Photographs by Gamboa Cabezas.

While the presence of two temporally distinct layers of small platforms suggest a continuity in function over time, the layers of stucco flooring and fill may represent an intervening period in which other activities took place, including domestic and figurine production activity. It seems more likely, however, that the fill and flooring were part of a large platform built to support the upper layer of small platforms, perhaps for protection from flooding, given the proximity of the river.

RIVER MEGALITHS

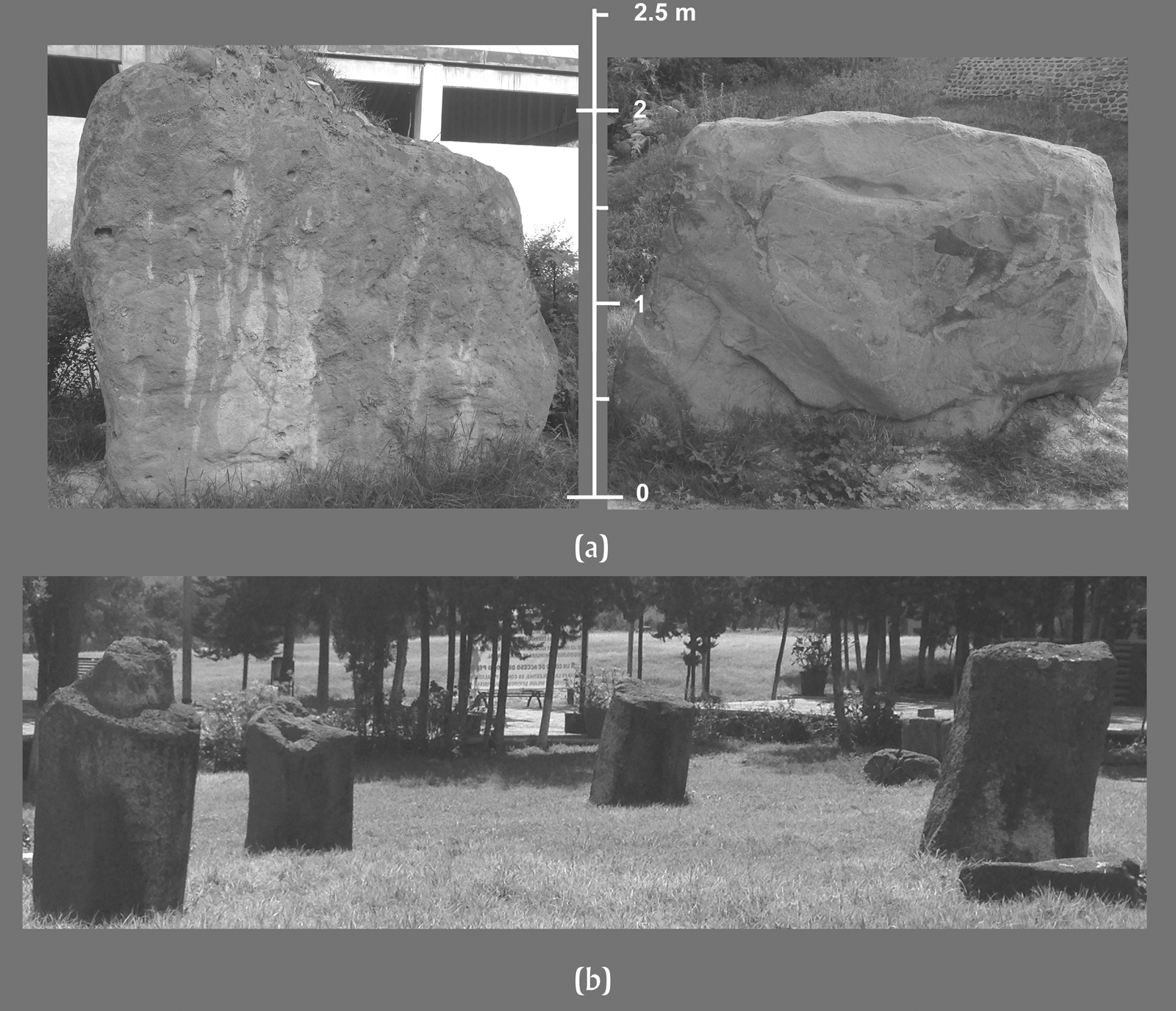

During the initial stages of canalizing the Tula River, two massive blocks of basalt were discovered within approximately 15 meters of each other in the bottom of the river channel, at its confluence with the Rosas River (Figure 1). Both specimens were roughly rectangular in form (Figure 7a), weighing an estimated 18 and 19 metric tons, and exhibit grooves, striations, depressions, impact scars, and other marks, presumably associated with extraction and/or initial processing.

Figure 7. (a) Basalt megaliths recovered from the Tula River; (b) basalt column preforms recovered from the banks of the Tula and Rosas rivers on display at the Museo Acosta. Photographs by Healan.

In fact, these are only the largest and most recently discovered specimens of numerous basalt monoliths found around the two rivers, but the first to be recovered from the river itself. Around 1995, the archaeologist Carlos Hernández (personal communication, 2007) used accounts by Garcia Cubas (Reference Garcia Cubas1873) and Charnay (Reference Charnay1887) of massive basalt objects partially hidden in vegetation along the river banks at Tula to locate and recover at least 11 massive basalt objects, including five preformed column sections with tenons, currently on display in front of the Museo Acosta (Figure 7b). None of these objects are nearly as large as the two megaliths from the river, and if they were used to make such preforms, megaliths of this size would probably have produced more than one.

The two megaliths and the preforms found by Hernández, together with the finished columns, pillars, and other basalt monolithic sculptures previously recovered from excavation at Tula, collectively provide a near complete chaîne opératoire that suggests a local industry that must have produced many other massive basalt sculptures at Tula besides those currently known to exist. Their recovery in and around the two rivers suggests they were transported by water from sources located somewhere upriver, and in fact Hernández (personal communication, 2007) successfully located basalt outcrops, and possible debitage indicative of quarrying and initial processing activity at two locations near the Tula and Rosas rivers, both upriver from Tula.

PROYECTO PREPARATORIO MORELOS

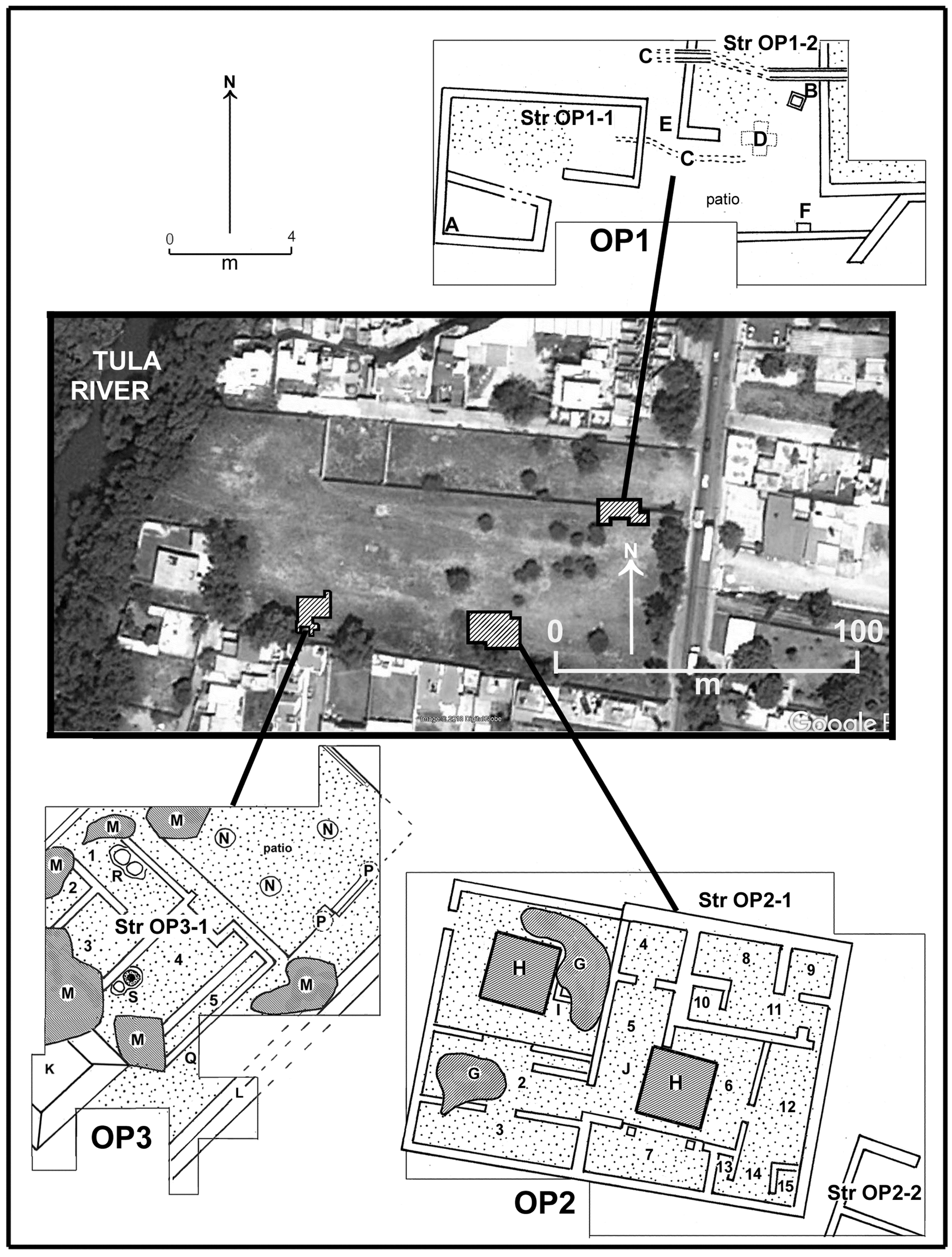

In 2011, an archaeological salvage project was initiated at the site of a proposed secondary school that was to involve the construction of five buildings. The site was located in the southern portion of the ancient city on the east bank of the Tula River (Figure 1), on a vacant tract, approximately 170 × 80 meters, within a highly developed modern urban neighborhood (Figure 8). Initial reconnaissance revealed that much of the northern portion of the tract had experienced extensive soil removal for prior construction in the area, hence the excavation strategy was to conduct test pitting in areas without obvious heavy modification. Unfortunately, construction of the school was already under way when the salvage project began, having proceeded as far as excavating some 25 zapatas, or large square pits to hold foundations of concrete and steel, although they had not yet been filled, and their placement over a large portion of the tract provided an alternative to exploratory excavation by examining their profiles and collecting associated artifacts. Many such profiles exhibited evidence of structural remains in varying degrees of preservation, although limitations of time and resources permitted intensive excavation of only three, designated Operations (OP) 1–3, located at widely spaced locations over the tract (Figure 8). Construction was temporarily halted in the areas being excavated, and subsequently suspended in one.

Figure 8. Map of the Preparatorio Morelos locality prior to construction, showing the location and architectural remains of the three operations at a common scale. Rooms are identified with Arabic numbers; letters refer to features discussed in the text. Google Earth Imagery; plan drawings by Healan and Gamboa Cabezas.

Each of the three operations exposed what appear to be portions of residential complexes that exhibited considerable variation in form, content, and other aspects that suggest differences in both function and social status. Excavation generally proceeded only to the uppermost intact remains, with limited deeper exploration. At least two operations encountered evidence of structures near the present surface that had been largely destroyed, hence the intact remains were not the latest. Therefore the three residential complexes seen in Figure 8 do not necessarily represent contemporaneous structures, but all were associated with Tollan complex ceramics (Tables 2 and 3), hence are part of a neighborhood that was apparently occupied throughout much of the Tollan phase. Each of these operations is described in the following sections.

Operation 1

The excavation exposed what appear to be portions of two multi-room residential structures designated Structures OP1-1 and OP1-2 (Figure 8), which appear to form the north and west sides of a house compound similar to those found elsewhere in Tula. House walls were typical of other Tollan phase residential structures—that is, foundation walls of stone cobbles consolidated with mud, over which courses of adobe blocks were laid to form the rest of the wall. Unlike those in the other two operations, no underlying substructure platforms were used, hence the two structures and adjacent patio were all at ground level. At least some floors had been covered with stucco. Each structure contained evidence of a hearth—a shallow subfloor brazier (Figure 8a) in Structure 1, and a subfloor stone slab-lined tlecuil (Figure 8b) in Structure 2. Although technically a tlecuil like others described in this article, this feature is smaller, more crudely constructed, and unaligned with the house walls. Because of the lack of supporting platforms for the adjacent houses, the central patio lacks the formal definition of others described in this article. What appears to be a freestanding wall along its south side suggests there were no other member houses.

The compound contained two in-floor drainage systems (Figure 8c), one of which, inside Structure OP1-2, was a stone-lined trough capped with stone slabs, while the other, in the patio, was simply a narrow open trench.

Two highly unusual subfloor burials were encountered (Figures 8d and 8e), both of which had been burned. One (Figure 8d) was placed beneath the entrance to Structure 2 in a shallow cruciform subfloor cist, lined and capped with stone slabs. The buried individual was wrapped in textiles and placed in a flexed position on the right side. Both the textiles and the upper surfaces of the bones were burned, as were the sides of the cist, indicating the burning was in situ. The other burial (Figure 8e), located in the passageway between the two structures that may have been the entrance to the compound, was more extensively burned, again in situ, given evidence of burning on the sides of the pit in which it was placed. It may have been a secondary burial, although the bones were too badly burned to determine. When present, burning of burials at Tula generally involved cremation, and rarely if ever involved burning of an in situ burial. That burial F was articulated, but with bones exposed to fire, raises the intriguing prospect that the burial was an articulated, textile-wrapped skeleton, or perhaps a desiccated corpse.

The freestanding wall at the south end of the patio contained a small, square receptacle (Figure 8f) constructed of stone slabs and capped with another slab. The receptacle was empty, but a broken zoomorphic vessel had been placed on top. The vessel lacked a head, but appears to be the effigy of a monkey seated on its legs, with its right hand holding its rather large belly (Figure 9). It could not be determined whether the damage to the vessel was post-depositional or if it were already broken, perhaps ritually “killed,” when placed atop the receptacle.

Figure 9. Frontal view of headless effigy monkey vessel recovered from top of receptacle (see Figure 8f) in Structure OP1-1, Preparatorio Morelos. Photograph by Gamboa Cabezas.

Limited excavation approximately 6 meters to the south exposed a portion of another structure designated OP1-3 (not shown in Figure 8) that appears to be part of a neighboring compound with the same spatial orientation, but with more spacious rooms with stuccoed floors and walls. Human remains encountered on one floor appear to have been intrusive burials from a later structure that had been destroyed.

Structures OP-1 and OP-2 do not exhibit the degree of architectural sophistication seen in the other structures encountered in excavation in this and the other localities, perhaps suggesting that their occupants were of a lower status than those of the other residential compounds. The placement of the monkey effigy vessel atop the receptacle in the patio is reminiscent of similar activity in several structures in the Vial locality described below and elsewhere at Tula, which may represent termination or dedicatory offerings that preceded construction that covered the remains of the structures and their offerings, which would explain how the effigy vessel had remained in place following abandonment. Although no overlying structural remains were encountered, the evidence from Structure OP-3 immediately to the south indicates the prior existence of later structures in the area. It is possible that the two rather shallow burials burned in situ were part of the same dedicatory activity, rather than interments that occurred during the occupation of the compound.

Operation 2

Located approximately 60 meters to the southwest, Operation 2 completely exposed one structure and the northwest corner of another, designated Structures OP2-1 and OP2-2, respectively (Figure 8). Very little of the latter structure was exposed and is not discussed here. Structure OP2-1, a rectangular building (approximately 8 × 12 meters) with 15 interior rooms, was damaged by two intrusions, presumably looters’ pits and two zapata pits (Figures 8 g and 8h). All of its walls were made entirely of adobe and faced with stucco, and appear to have been erected on a low platform. Access was provided by a single narrow entranceway in the northwest corner.

Given their rather large number considering the size of the structure, some of the rooms are rather small, although some may be later partitions of existing rooms. Room 1, the largest room, was extensively damaged by a zapata pit and an intrusion. Remnants of a small platform (Figure 8i), possibly an altar, were encountered on the east side of the room.

Rooms 5 and 6 were badly damaged by the other zapata pit. Room 5 contained a subfloor brazier (Figure 8j) on its west side, and along the south side of room 6 was a wide entranceway supported by two pillars leading into room 7. The combination of a wide, pillared entranceway on one side and a subfloor brazier on the other suggests that rooms 5 and 6 contained an interior patio precisely where the zapata pit was placed. Excavation beneath the east pillar in room 7 recovered a small textile bag containing a large number of small rounded concretions that have been identified as endoskeletal remains of starfish (Francisco A. Solís Marín, personal communication 2020). The bag also contained an unspecified number of maguey spines commonly associated with bloodletting, suggesting its contents were objects used in ritual, which in this context would appear to have been a dedicatory offering.

The large number of rooms and their clustered layout suggests Structure OP2-1 was an apartment compound within which were housed multiple families. Three distinct east–west room clusters, consisting of rooms 1–3, 4–7, and 8–11, and 12–15, with rooms 1, 2, 5, and 6 perhaps serving as more public areas providing access between them. Structure OP2-1 is strikingly similar in form to Teotihuacan apartment compounds (e.g., Millon Reference Millon and Wolf1976:Figure 13), but considerably smaller considering its width of 13 m compared, for example, to 60 m for the Yayahuala, Teotihuacan compound. Rather than calling Structure OP2-1 an apartment compound, we prefer to use a more descriptive term, room cluster compound, which does not assume it was a multifamily dwelling.

Operation 3

Located near the southwest end of the locality immediately adjacent to a large mound (Figure 8), excavations in OP3 partially exposed a well-preserved Tollan phase house compound with a distinctive (52 degrees east of north) orientation, containing a large central patio flanked by houses on at least the southwest side, and probably the northeast side as well, given the stairway at the northeast end of the patio. A third house may also exist on the unexcavated northwest side.

No structural remains were encountered atop the rather narrow southeast platform, whose stairway provided a second point of access to the patio. Excavation partially exposed the exterior wall of the platform (Figure 8l), a two-tiered structure approximately 1.8 meters in height that may have been faced with carved stone panels, as suggested by the recovery of a portion of a carved panel in front of the platform wall, containing a representation of the hombre-jaguar-pajaro-serpiente (h-j-p-s) image seen on Pyramid B at Tula Grande (Jiménez García Reference Jiménez García2021). Limited excavation of the platform interior revealed a system of cajones like that encountered in the PRADRT-1 locality, in this case a grid of adobe walls containing rock fill.

As with the other operations in this locality, associated ceramics were Tollan complex. Exploratory excavation confirmed that the adjacent mound was a pyramid (Figure 8k), which overlay the rear portion of Structure OP3-1. Associated ceramics and the use of tabular small stone facing, a common decorative element of Tollan phase architecture, indicate that the pyramid also dated to the Tollan phase.

A prominent feature of OP3 is a circular arrangement of six intrusions that may have been created by trees (Figure 8m), although the regularity of several and their location on and adjacent to the pyramid suggest at least some were looters’ pits. A coin dated 1833 was encountered in excavation in front of the southeast platform exterior wall, at a depth of approximately 1.8 meters.

All floors associated with the OP3 residential compound were covered with stucco, including the patio floor, which is at ground level, while the surrounding structures were built atop platforms. The patio contained three circular features (Figure 8n) constructed of stone and mud that appear to be column bases, presumably three of four centrally located columns in a patio that would thus have been approximately 11 meters wide, essentially square. Exploratory excavation beneath the three column bases encountered an earlier stucco floor with square post molds, which, though situated directly beneath the overlying column bases, did not penetrate them, indicating the underlying wood posts and overlying masonry column bases are temporally distinct features corresponding to their respective floors.

Patios with four central supports are a common feature of high-status buildings at Tula, and in most cases appear to support an atrium, or opening in an otherwise roofed-over patio. In the case of an exterior patio like the OP3 compound, the opposite might the case—that is, the columns are associated with a small roofed-over area in an otherwise unroofed patio. In fact, two additional column bases (Figure 8p) were erected over the stairway on the southeast side, clearly later additions that may represent an eastward extension of the central roofed-over area, although in a rather makeshift fashion.

Unusual discoveries in Structure OP3-1

Structure OP3-1, a multi-room, residential structure located on the southwest side of the patio, provided some of the most spectacular and unusual finds to date from Tula. The rear (southwest) portion was obscured by the overlying Tollan phase pyramid and several intrusions, but the southeast exterior wall of the structure did not continue past the intrusion at the rear of room 5, providing an approximation for its rear (southwestern) limits that indicate the structure was rectangular, measuring approximately 6 × 8 meters, and contained five interior rooms. Like Structure OP2-1, all walls were made of adobe and both floors and walls were stuccoed. Also like Structure OP2-1, access was limited to a relatively narrow entrance in the northwest corner, which was partially obscured by an intrusion.

During excavation, Structure OP3-1 was found to contain large amounts of what appears to be de facto refuse littering its floors, along with charcoal and ashy soil. Many of the objects had been burned and appear to have been intentionally broken, suggesting systematic destruction that had occurred, presumably at the time the structure was abandoned.

At least 12 broken Tojíl plumbate vessels were found on the floor of room 3, portions of six of which are shown in Figure 10. These included at least five anthropomorphic vessels, including two with representations of crouching individuals, one of which was holding an atlatl (Figure 10d). The widespread spatial distribution of fragments from each vessel suggests they had been intentionally smashed, hurled to the floor with sufficient force to produce a wide scatter. The vessels included two human heads (Figure 10d), both of whose faces had been partially damaged, perhaps intentionally. While some vessels appear to be reconstructible or nearly so, others were incomplete, to some extent a likely result of widely scattered pieces having been recovered as general-level artifacts. Some specimens, however, are so incomplete they may have been partially removed prior to entering the archaeological state or may have been partial specimens to begin with.

Figure 10. (a–f) Selected portions of broken Tojíl plumbate vessels; (g) fragmentary mineralized megafaunal remains, all from Structure OP3-1, Preparatorio Morelos. All objects at same scale. Photographs by Healan.

Two large, mineralized bone fragments (Figure 10) were recovered from the floor of the passageway along the southeast side (Figure 8q). The pieces appear to be parts of one or two rib bones of a species of megafauna, possibly a mastodon.

In rooms 1, 4, and 5, the floors were littered with fragments of worked bone and shell, much of which had been burned, including engraved shell and engraved human bone that included portions of a skull. In room 4, a large engraved shell pendant was encountered in a burned and fragmentary state, much of which was recovered and reassembled (Figure 11). The pendant, now on display in the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City, was the subject of a recent technological and iconographic study (Castillo Bernal et al. Reference Castillo Bernal, Castro and Maldonado2019), which identified the shell as a giant Mexican limpet (Ancistromesus mexicanus), a species native to the Pacific Ocean. The shell is oval in shape, measuring roughly 28 × 21 cm, and although burned, clearly exhibits engraved images, including an elaborately attired male sitting cross-legged and brandishing an atlatl and two darts, partially surrounded by a feathered serpent, a partial human figure brandishing an atlatl, and a human skeletal figure also brandishing an atlatl (Figures 11a–11c). The cross-legged individual is of particular interest given his portrayal with a feathered serpent, a juxtaposition that in other occurrences at Tula has been interpreted as identifying the accompanying individual as a ruler (Báez Urincho Reference Báez Urincho2021; Jiménez García Reference Jiménez García2021). Castillo Bernal et al. (Reference Castillo Bernal, Castro and Maldonado2019:68) identified the individual as a ruler known as Lord Puma (Cobean et al. Reference Cobean, García and Mastache2012:160; see also Jiménez García Reference Jiménez García2021), given the representation of the head of a feline believed to be a puma at his feet.

Figure 11. Carved shell recovered from room 1, Structure OP3-1, Preparatorio Morelos. Drawing by Gamboa Cabezas.

Rooms 1 and 4 each contained two large, cylindrical subfloor pits arranged side by side (Figures 8r and 8s). The two inside room 1 contained large numbers of sherds that appear to represent multiple vessels broken in situ. In room 4, the smaller of the two pits contained only a few sherds, but the larger pit contained a whole Soltura Smoothed Red (Tollan complex) olla (Figure 11). Although rather large (approximately 60–70 centimeters in diameter), the olla was not as wide as the pit, hence was not a built-in feature. The lower portion of the vessel contained carbonized human bone (Figure 12a) and a number of sumptuous objects, including the first known gold artifacts from Tula. The bones were heavily charred and formed an unarticulated mass, oriented roughly east–west, suggesting they had been bundled, and the quantity and size suggest the remains of one adult individual. Beneath the human remains at the very bottom of the olla were around 70 cylindrical bone beads (Figure 12b) that may have been articulated in one or more strings.

Figure 12. Side and top views of olla and its contents from room 4, Structure OP3-1, Preparatorio Morelos. (a) Burned human bone; (b) cylindrical bone beads; (c) carbonized wooden billet; (d) polished obsidian mirror; (e) shell disk with mosaic; (f–h) worked shell; (i) gold-leaf cruciform objects. Photographs by Gamboa Cabezas; drawings by Healan.

Overlying the charred bones were two layers of objects. The topmost object was a carbonized wooden billet (Figure 12c) that was promptly removed and covered before detailed examination, but measured approximately 30 × 6 centimeters, rounded in cross-section, and apparently tapered at one end. It had been placed along the midline of the interior, oriented approximately north–south, hence perpendicular to the underlying bundle of bones.

Beneath the wooden billet were two clusters of objects located in the southeast and southwest quadrants of the interior and resting upon the carbonized bone layer. In the southwest quadrant, two elaborate discoidal objects were found stacked one atop the other (Figures 12d and 12e). The upper object is a plano-concave ground obsidian disk, approximately 11.5 centimeters in diameter, whose concave surface is a highly polished mirror (Figure 13a). The flat underside exhibited a resin-like residue that indicated it may have been affixed to some type of backing (Figure 13b). While this is the only complete find of such an object reported for Tula, a fragment of another polished obsidian mirror of comparable size and form was recovered during the excavation of an obsidian workshop in the northeastern part of the urban zone (Healan et al. Reference Healan, Kerley and Bey1983).

Figure 13. Objects from inside olla from room 4, Structure OP1-3, Preparatorio Morelos. (a) Polished obsidian mirror, front view, with remnant in situ mosaic covered with paraffin; (b) polished obsidian mirror, rear view with shell disk in situ; (c) shell disk, front view with blue and green stone pieces, including human head; (d) green stone disk with stone and shell mosaic that had probably overlain obsidian mirror; (e) elongated shell object; (f) rectangular gold-leaf object; (g–h) cruciform gold-leaf objects. Photographs by Gamboa Cabezas.

The lower object, a much smaller shell disk (approximately 4.5 centimeters), lay directly under the mirror (Figures 12e and 13b). Its upper surface was encrusted with a mosaic that had largely disintegrated, residual components of which included rectangular pieces and a human head of blue and green stone, possibly turquoise (Figure 13c). The disk was surrounded by scattered pieces of worked shell, green stone, and blue stone, presumed to be debris from the mosaic, and is now undergoing restoration at the Museo Nacional de Antropología.

The concave obsidian mirror surface was partially covered by a badly disintegrated mosaic of worked shell and blue and green stone that was immediately covered in paraffin to stabilize it (Figures 12f and 13a). While it was initially assumed that these remnants had been affixed to the mirror surface, the materials surrounding the mirror included numerous fragments of another discoidal object, a flat ring of bluish-green stone, essentially the same diameter as the shell disk (Figure 13d). We believe this disk had been placed on top of the obsidian disk (Figure 12f), and included the remnants of stone and shell on the mirror surface.

The second cluster of objects, located in the southeast quadrant, include three worked shell objects and three objects of gold leaf. The shell objects (Figures 12g and 12h) include a perforated disk, a perforated pendant, and an oblong piece. The gold-leaf objects include a rectangular specimen and two cruciform specimens (Figures 12i, 13f–13h), the former partially folded around the oblong shell piece (Figure 13e). Their proximity suggests all were components of one or more objects of perishable material that probably included textiles, given the perforations on the shell objects.

We presume the contents of the olla were the product of a single act, involving the placement of beads, charred human remains, mirror and mosaic disks, textiles, and/or other perishable objects containing the gold and shell pendants and, finally, the wooden billet. The question of when this event occurred is considered below.

Given the importance of these finds and the possible presence of related materials in the unexcavated parts of the residential compound, OP3 and the surrounding area has been declared a protected area and construction permanently halted in that portion of the tract where buildings were to be constructed.

Discussion

Given the discontinuous nature of the excavations in the Preparatorio Morelos locality and evidence of multiple episodes of construction, it is not known whether or how much the residential complexes in Operations 1, 2, and 3 overlapped in time, but they nonetheless represent components of a neighborhood that was apparently occupied continuously during much of the Tollan phase. Their location near Tula's southern limits provides the first view of residential life in a previously unexplored portion of the ancient city, given that all other residential excavations to date are located much further to the north (Healan Reference Healan2012:Figure 3).

It is surprising that the residential complexes in the three operations did not share a common orientation, since structures in close proximity in other excavated localities at Tula commonly do so. The three also exhibit considerable diversity in form and overall architectural quality, a characteristic of residential structures in other localities. The orientation of the OP3 complex is rather extreme compared to that of the other structures described in this article, but the partially overlying pyramid exhibits the same orientation (Figure 8k)

Note that most, if not all, of the bone and shell recovered from the floors of Structure OP3-1 appear to be fragments of finished objects and did not include unworked material, rejects, and other debitage normally found in production loci. Thus the material was not the result of production activity, but rather breakage of finished objects, often involving considerable fragmentation and displacement indicative of hurling and smashing. We believe that this does not represent looting but rather iconoclastic activity that was also directed at the plumbate vessels, the megafaunal remains, and perhaps vessels stored in the subfloor pits in rooms 1 and 4, with the exception of the intact olla in room 4, which, to our considerable fortune, was untouched. It seems unlikely, however, that those involved in the iconoclastic activity would have failed to notice the olla. More likely, it was intentionally spared, or in fact was placed there as part of the activity that included iconoclasm and burning.

We presume this activity occurred at the time that Structure OP3-1 was abandoned, which would have been well before the end of the Early Postclassic city, given the subsequent construction of the Tollan phase pyramid that partially overlay it. Hence, rather than the product of disruptive forces that may have accompanied Tula's demise, the source of this activity would seemingly have been internal, perhaps part of a ritual termination of Structure OP3-1 prior to construction of the pyramid, a situation similar to what apparently took place prior to the construction of the Southwest Pyramid at Tula Chico (Cobean et al. Reference Cobean, M. Healan and Suárez2021). That both the pyramid and the OP3 complex exhibit the same, rather extreme orientation suggests a close tie between the two.

Presumably, the burning of the structure was also part of the ritual termination, and followed the iconoclastic activity in time, given that many of the shell and bone objects had been burned. We believe that the olla containing the human remains and other objects was placed in the cylindrical pit in room 4 as part of this activity. The charred nature of the overlying wood object might indicate the olla was placed there prior to burning the structure, except that none of the objects immediately beneath the wood object showed any signs of exposure to heat other than the burned human bones, which are clearly the result of a prior cremation. Thus it appears that both the human remains and the wood object were burned prior to being placed inside the olla, and the olla placed in room 4 after the structure had burned.

In their study of the engraved shell object shown in Figure 11, Castillo Bernal et al. (Reference Castillo Bernal, Castro and Maldonado2019:71) concluded that the structure in which it was found (Structure OP3-1) was a residence of Toltec elite and that the object itself had belonged to a member of the lineage of Lord Puma, the central individual on the shell pendant, perhaps Lord Puma himself, considering the richness of the associated artifacts in the structure, although they erroneously placed it a few hundred meters below Tula Grande rather than its correct location, approximately 2 kilometers to the south (Castillo Bernal et al. Reference Castillo Bernal, Castro and Maldonado2019:Figure 1). We agree that the richness and diversity of the prestige goods recovered from the olla and elsewhere in Structure OP3-1 suggest its occupants were individuals of high status, but not necessarily part of Tula's ruling lineage.

Castillo Bernal and his colleagues also note several potentially intriguing parallels between Structure OP3-1 and the Casa de las Aguilas of Aztec Tenochtitlan (López Luján Reference López Luján2006:200, 247–267), where investigators encountered offerings of engraved shell pendants that had been burned, an offering involving a rich array of artifacts, and three cylindrical pits containing ceramic vessels with the cremated remains of a single individual, although Castillo Bernal and his colleagues were apparently unaware that the Structure OP3-1 olla likewise contained cremated human remains. Unlike their counterparts in Structure OP3-1, however, the engraved shell objects and offering in the Casa de Aguilas were from several different contexts, and the engraved shell from Structure OP3-1 was broken, found on the floor, rather than as a buried offering, as Castillo Bernal et al. mistakenly claim, hence the two contexts are not as similar as they appear. In fact, a much more direct parallel between Tula and the Casa de las Aguilas is provided by Edificio 4 in Tula Grande (Báez Urincho Reference Báez Urincho2021).

PROYECTO PROCURADURÍA GENERAL DE LA REPÚBLICA

Between 2007 and 2010, salvage excavations were conducted at the proposed site of the regional headquarters of the Procuraduría General de la República (PGR). The site was a tract of land that incorporated several parcels of mixed agricultural, commercial, and residential use, situated immediately east of the southeast corner of the protected archaeological zone (Figures 1 and 13).

The first (2007) field season was initially exploratory, but eventually focused on partial exposure of a residential compound designated Operation 1 (OP1), which uncovered one of the most macabre discoveries ever made at Tula. Additional investigations were undertaken in 2009, when a second find of major interest led to the partial exposure of additional structural remains in two adjacent areas designated Operations 2 and 3, situated approximately 7 meters and 12 meters to the southeast of OP1 (Figures 14a–14c). Each of these operations and their associated finds is discussed below.

Figure 14. Plan of the OP1 complex, Operation OP1, PGR locality, and location of the three operations in the locality (inset). (a) Stone head; (b) human remains inside altar. Google Earth Imagery; plan drawing by Healan and Gamboa Cabezas.

OP1 Complex, Feature 5

Investigations in 2007 focused on a vacant tract that was previously under cultivation. A 50 × 50 m grid was imposed over the area, aligned to the existing property lines (approximately 50 degrees west of magnetic north), within which exploratory excavations took place, involving 16 pits, measuring 2 × 2 m, at various locations based on surface topography and artifact density. Thirteen pits yielded structural remains, including walls, floors, and other features, including two burials. Some remains were badly damaged by land leveling that had occurred in recent years. Given limitations of time and resources, more extensive excavation was limited to what became OP1, situated near the center of the tract (Figure 13a), where exploratory excavation had encountered sculpture fragments and structural remains in good condition.

Excavation partially exposed a house compound, hereafter referred to as the OP1 complex, containing an open patio and surrounding passageway, and raised platforms supporting structures on all four sides (Figure 14). The patio sides were faced with a small stone veneer, its floor stuccoed and accessed by a single step on the platform along the east side, atop which were the remains of a virtually destroyed building designated Structure OP1-1. A surmounting structure, designated Structure OP1-2, was also encountered on the platform along the west side (Figure 14), although the exposed portion included no entrance from the patio passageway. The platforms along the north and south sides were heavily eroded, but contained traces of stucco flooring and adobes, indicating that they, too, had held structures, although the only platform with direct access to the patio was the one on the east side.

The central patio contained a prominent rectangular altar abutting the western wall (Figures 14 and 15). The altar was badly damaged and appeared to have been partially dismantled during prehispanic times. Its interior contained a loose fill, containing portions of a skull, long bones, and other bones (Figure 14b) of a child, presumed to represent at least a child burial that had been partially removed. A stone replica of a human head was found lying on top of the altar (Figures 14a and 15), which bore traces of red paint and was part of a larger sculpture that was not found. A strikingly similar find of a stone human head, likewise associated with a partially dismantled altar from which a burial had apparently been removed, was encountered in the patio of a residential compound in the Canal locality (Healan Reference Healan1989:126, Figure 9.20). A portion of a carved panel found nearby appears to be a representation of the h-j-p-s image like those seen on Pyramid B at Tula Grande (Jiménez García Reference Jiménez García2021).

Figure 15. Detail of patio, OP1 complex, PGR. (a) Distribution of 11 of the 18 complete or near-complete individuals, mostly children, in Feature 5 beneath patio floor; (b) individuals in situ, looking southwest; (c) impressionistic sketch of original placement of 11 individuals, looking southwest. Photograph and plan drawing by Gamboa Cabezas; impressionistic sketch by Healan.

Exploratory excavation beneath the patio floor in front of the altar encountered human skeletal remains, prompting more extensive excavation that ultimately exposed the remains of a large number of individuals, mostly children. Collectively designated Feature 5, the remains formed an arc-shaped distribution in front of the site of the later altar (Figure 15a). Most were partial or fragmentary skeletons, but 18 were complete or nearly complete, articulated individuals that had been placed in a sitting or squatting position, facing east (Figures 15b and 15c; only 11 individuals are indicated in Figure 15 because some had already been removed and others had not yet been uncovered). Numerous Tollan complex ceramic vessels were placed among the individuals, as well as a whole Mazapa-style figurine. One individual was associated with two copper bells, one of which was recovered from inside the mouth. Limitations of time and resources prevented additional excavation to determine whether Feature 5 extended further to the east, but evidence of similar activity was encountered in OP2 and OP3, described below.

Medrano Enríquez (Reference Enríquez and María2021:Table 2) estimates that Feature 5 includes the remains of 49 individuals, 43 of whom were below the age of ten and 33 below the age of two years. While initially described as a series of “burials,” it is more accurate to characterize Feature 5 as a single burial or mass deposit of individuals, mostly children, many arrayed in a theatrical, if macabre, manner. Medrano Enríquez suggests these individuals had been sacrificed to the deities of water and fertility, although Xipe Totec may also have been involved, given his association with regeneration, plus the find of a large Xipe sculpture in OP3, described below.

The individuals of Feature 5 had been placed on a natural surface a few centimeters above tepetate prior to construction of the overlying OP1 complex. Besides Feature 5, the intervening space between this surface and the overlying patio floor (approximately 50 centimeters) was filled with artifact-rich soil, presumably fill introduced to cover the individuals and provide a foundation for the overlying house compound. That 18 of the 49 individuals were in an undisturbed, articulated state suggests that Feature 5 was covered over rather quickly, and their distribution around the site of the later altar suggests knowledge of its impending construction. Therefore it appears that the mass sacrifice and the subsequent construction of the OP1 house compound probably occurred very close to each other in time, suggesting the sacrifice was a dedicatory ritual activity preceding construction of the OP1 complex in what was previously open terrain.

OP2 and OP3

In 2009, additional excavations were conducted at the PGR locality in an adjacent tract where construction activity had encountered the head of a large, hollow ceramic figure that appeared to represent the deity the Aztecs called Xipe Totec. OP3 was conducted in the area where the ceramic head was found and located the remainder of the figure (Figure 16f). Subsequent excavations, designated OP2, were undertaken in the area between OP1 and OP3.

Figure 16. Map of structural remains and associated finds in OP2 and OP3, PGR locality: (a–d) human skeletons; (e) patio with stucco floor; (f) hollow ceramic figure representing Xipe Totec. Photograph by Gamboa Cabezas; plan drawings by Healan and Gamboa Cabezas.

OP2

The OP2 excavations exposed the eastern and western ends of two adjacent, well-constructed platforms and an intervening open passageway (Figure 16). Each platform supported remnants of stone walls and stucco flooring of surmounting structures, designated Structures OP2-1 and OP2-2. Given its proximity and comparable distance below surface, Structure OP2-1 is almost certainly the eastern end of Structure OP1-1 immediately to the west (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Harris matrix showing stratigraphic relationships and relative order of construction and other events in the PGR locality. Image by Healan.

The intervening passageway contained the remains of four largely articulated individuals (Figures 16a–16d), at least three of whom appeared to have been placed in a sitting position against the Structure OP2-2 platform, facing west. Two individuals were associated with Tollan phase ceramic vessels, and one had ear spools and a cut shell pendant similar to that associated with the Aztec deities Ehecatl and Quetzalcoatl. These individuals would appear to represent a sacrificial act similar to, but later in time than Feature 5, as discussed below.

OP3

Extensive excavation in the area where the Xipe sculpture was recovered exposed what was designated the OP3 complex, which included the northwest corner of a stepped platform designated Structure OP3-1 (Figure 16) and an adjacent open area floored with stucco (Figure 16e), presumed to be a patio of undetermined size that was partly destroyed by modern construction activity. The surface of Structure OP3-1 was paved with a layer of sherds, an architectural feature associated with altars in other excavations, although the presence of steps and its large size (at least 2.3 meters in width) suggests it was an adoratorio like that found in the center of the plaza at Tula Grande.

Immediately in front of the Structure OP3-1 steps, excavation encountered a shallow pit containing the body of the hollow ceramic Xipe figure (Figure 16f), which exhibited attributes that confirmed its identification as Xipe Totec (García Sánchez et al. Reference García Sánchez, Cabezas, Berelleza and González2016). The complete figure, measuring 0.85 m in length, compares favorably to other hollow ceramic representations of Xipe from elsewhere in Mesoamerica. The pit containing the figure had been dug through the stucco floor; it abutted rather than underlay the platform steps, and was covered with stone slabs, hence clearly post-dated construction of the OP3 complex. The complex was overlain by fill and rubble associated with a later structure designated Structure OP3-2, almost certainly the eastern portion of Structure OP2-2, given its proximity and distance below surface (Figure 17).

Discussion

As seen in Figure 17, the likely identification of Structures OP1-1 and OP2-1, and likewise Structures OP2-2 and OP3-2, as parts of the same structures and their shared passageway in OP2 establishes their contemporaneity and provides a temporal order to the various events that took place in the PGR locality. It appears that the earliest known occupation involved the OP3 complex, which, if Structure OP3-1 was indeed an adoratorio, may have been part of a more substantial structural complex than simply a residential compound. The comparable stratigraphic positions of Feature 5 and the Xipe burial suggest that both events occurred at the same time as part of a dedicatory ritual, prior to the construction of the neighboring complexes. The four individuals in the intervening passageway (Figurea 16a–16d), at least three of which had been placed in a sitting position, appears to represent a continuation of this kind of ritual activity, perhaps as a dedicatory offering for subsequent construction that has since been destroyed in light of recent land-levelling activity.

DISTRIBUIDOR VIAL

From 2006 to 2008, an archaeological rescue project was conducted at the site of the Distribuidor Vial, a proposed highway interchange on the eastern edge of Tula de Allende that lay in the southern portion of the ancient city (Figure 1). This project was wholly different from the others reported here, in two ways: construction was already well under way, involving extensive bulldozing and excavation of zapata pits, and because INAH had no authority over the construction, the project was a rescue rather than a salvage operation. Twelve areas within the construction site were targeted for exploratory excavation, based upon materials and features that had been encountered during construction, and excavation in six of them was subsequently expanded. All six of these excavations, designated Operations (OP) 1–6, are described below, while only Operations 2–5 are shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18. Map of the Distribuidor Vial locality after construction, showing the location and architectural remains of Operations 2–5 at a common scale. Rooms are identified with Arabic numbers; letters refer to features discussed in the text. Google Earth Imagery; plan drawings by Healan and Gamboa Cabezas.

OP1

OP1 was a brief undertaking in which the face of a deep bulldozer cut was cleaned, revealing two burials and other prehispanic remains. Like the two burials in Structure OP1-1 in the Preparatorio Morelos locality, one of the burials had been burned in situ, containing two vessels that were also burned. Adjacent to the burials was a partially exposed stairway, with flanking alfardas and a series of superposed walls and floors. The stairway may represent a barrio-level temple, like those encountered elsewhere at Tula (Paredes Gudiño and Healan Reference Paredes Gudiño and Healan2021; Stocker and Healan Reference Stocker and Healan1989). The two burials were removed, but no further investigation of the temple and nearby structures was possible. Associated ceramics suggested a Terminal Corral phase occupation (Tables 2 and 3).

OP2

OP2 was conducted around a zapata pit whose profile revealed remains of at least two superposed structural complexes, both dating to the Early/Late Tollan phase. The earlier complex is a partially exposed house compound, including an open patio flanked by two structures, designated Structures OP2-1 and OP2-2, on the north side, and a third structure or freestanding wall on the south side (Figure 18). Limited excavation in the northeast corner of the operation encountered a stucco floor, likely a continuation of Structure OP2-2. Both structures and patio were floored with stucco. The patio contained a tlecuil (Figure 18a) that was relatively small, not well-constructed, and unaligned with the house walls, and partially exposed a rectangular altar (Figure 18b) that was not excavated due to limitations of time. Structure OP2-2 contained two whole metates placed upside down in the corner of one room (Figure 18b), along with a complete cigar-shaped mano. Both structures were overlain by several adobe walls (Figure 18e) and a stucco floor (not shown) that were part of the later, unnamed structure that had been largely destroyed. Limited excavation in the southeast corner of the operation encountered two walls of an unnamed platform (Figure 18d), whose depth below surface suggests it was part of an earlier, unnamed structure.

OP3

Excavations in OP3 encountered two superposed Tollan phase structural complexes, designated Structures OP3-1 and OP3-2. Structure OP3-1, the earlier of the two, is the northern portion of a large structure with exterior and interior walls of adobe (Figure 18f) enclosing three interior rooms whose floors and walls were stuccoed. Room 2 contained a small, well-built tlecuil (Figure 18g) and a rectangular altar (Figure 18h) constructed of adobe faced with tabular stone, which was excavated but contained no offering. Several broken ceramic vessels were encountered on the room 2 floor (Figure 18i). The tlecuil contained an unspecified number of whole, unburned avian skeletons, possibly a dedicatory offering prior to constructing the overlying Structure OP3-2. Remains of two species of tropical birds (Ara militari and Amazonia finschi) were encountered in human burials in salvage excavations at the site of the Museo Acosta (Paredes Gudiño and Healan Reference Paredes Gudiño and Healan2021; Valadez and Paredes Reference Valadez and Paredes1990), but the individuals in Structure OP3-2 were not identified as to species. The overlying, unnamed structure in OP3 was largely destroyed, but the exposed portion consisted of two stone walls (Figure 18j) delineating two large rooms.

OP4

OP4 was initiated in an area where a bulldozer had uncovered a carved stone panel depicting a disc with a radial motif like those Acosta (Reference Acosta1957:Lámina 6) found in Edificio 3 at Tula Grande. Excavation did not recover additional sculpture, but did encounter the remains of two superposed structures, both dating to the Tollan phase. The later, unnamed structure was badly damaged; indeed only a single, wide, well-built stone wall was encountered (Figure 18k). The earlier structure, designated Structure OP4-1, included several adobe walls enclosing three rooms with stuccoed adobe walls and floors. Room 2 appears to be the northern half of an interior patio containing two of presumably four central columns (Figures 18l and 18m) and a tlecuil (Figure 18n), which appears to lie at the center of a square patio about 7 meters wide. A large, unidentified (non-Tollan complex) ceramic vessel was found on top of the tlecuil, possibly a termination or dedicatory offering preceding construction of the later structure.

The northwest corner of room 2 contained a bench abutting the north and west walls, and a well-constructed, nearly square altar abutting the north wall (Figures 18o and 18p). The altar was intact, consisting of a single talud faced with tabular stone covered with stucco, with a top constructed of adobe, likewise covered with stucco. The altar contained 22 whole vessels and a mass of carbonized human bones, presumably a cremation burial. One of the most notable aspects of the 22 vessels recovered from the altar is that they include both Tollan complex vessels and vessels identified as Aztec Polished Orange, a very common, but non-diagnostic ceramic that occurs in all four (Aztec I–IV) Aztec ceramic periods, but one vessel had a type of support considered diagnostic of Aztec I. Aztec I appears to overlap in time with Tollan phase Tula (Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Brumfiel and Hodge1996:227–229), but this is the only other documented occurrence of Aztec I ceramics at Tula, besides a single sherd from Pyramid B at Tula Grande, recovered and described by Acosta (Reference Acosta1941:245; Reference Acosta1944:154, Figure 31).

OP5

Excavation in OP5 encountered remains of three superposed Tollan phase structures, designated Structures OP5-1, OP5-2, and OP5-3 in Figure 18. Structure OP5-3, the uppermost and latest of the three, consisted of the east end of a large building and underlying platform, whose east retaining wall was faced with tabular stone (Figure 18q). The surmounting structure and platform surface were virtually destroyed, exposing an underlying, artifact-rich fill that included a fragment of a carved stone that appeared to be another h-j-p-s representation like those encountered in the Preparatorio Morelos and PGR localities, and on Pyramid B at Tula Grande (Jiménez García Reference Jiménez García2021). Excavation in the western portion of OP5 removed the Structure OP5-3 platform fill and exposed the underlying Structure OP5-2 (Figure 18); likewise an ill-defined building atop a platform whose surface was paved with cobblestones, with two stone-lined trough drains embedded in its surface (Figure 18r). Little evidence of the surmounting building remained, and is presumed to have been largely removed during construction of the overlying Structure OP5-3 platform. Two burials with Tollan complex vessels were found intruded into the cobblestone surface, and are presumed to have originated from Structure OP5-3.

Structure OP5-1, the earliest structure, was encountered in the eastern half of OP5 and included three partially exposed rooms. The western half of room 1 and whatever lay beyond were covered by the two later structures. The walls separating rooms 1–3 were made of adobe, and walls and floors were stuccoed. Like Structure OP2-2, Structure OP5-1 contained two whole metates and a cigar-shaped mano, the metates placed one behind the other, face down on top of the wall between rooms 1 and 2 (Figure 18s). Perhaps the metates were placed on the adobe wall after the structure had been razed, part of a termination or dedicatory ritual prior to the construction of Structure OP5-2. Alternatively, the “wall” may have been only a low partition and the metates placed there while the Structure was still standing or even occupied.

Room 1 contained a highly unusual find consisting of two painted adobe blocks, lying face up on the floor along the east wall (Figures 18t and 19). Each exhibited a vibrant, highly detailed polychrome representation in intense colors of black, red, yellow, and blue, in a style strongly reminiscent of Mixteca-Puebla codices. Unfortunately, both blocks had been damaged, so the overall representation is unclear on either specimen. One of the two (Figure 19a) includes what appears to be the head of a feathered serpent facing left, while the other (Figure 19b) depicts what may be an upright human figure, facing and possibly moving to the left. These objects are unique among artistic representations at Tula, certainly some of the finest quality art yet to be discovered.

Figure 19. (a and b) Painted adobes encountered in Operation 5, Distribuidor Vial locality. Photograph by Healan.

A surprising feature of both representations is that they were applied directly to the unprepared, irregular surfaces of the two blocks, which are themselves irregular in form. One possible explanation for this wholly paradoxical combination of superior art and inferior media is that the adobes were revered relics, perhaps from structures with high symbolic value.

OP6

OP6 was located on the roadway approximately 200 meters south of OP4, where bulldozers removing two existing, superposed highway pavements encountered human bones beneath the earlier pavement. An intact column base was also exposed, indicating that one or more structures had existed in the area, which had apparently been destroyed by construction of the earlier roadways. Some 17 burials were encountered during excavation, and are presumed to have been buried beneath the floors of the structures that had existed there. Many contained grave goods, mostly ceramic vessels, but one burial also contained a whole metate, while another contained two whole obsidian prismatic cores. Most of the ceramic grave goods were diagnostic Tollan complex vessels, but one of the burials contained exclusively Aztec III ceramics. This appears to be yet another instance of the Aztec placing burials in Tollan phase structures, a practice that appears to have been widespread at Tula (Healan et al. Reference Healan, H. Cobean and Bowsher2021).

EJIDO HUERTO DE NATZHA

The increase in population that has accompanied industrialization and development in the Tula region has generated settlement in areas that were previously unsettled, or sparsely so. One such area is Cerro Magoni on Tula's western flank (Figure 1), which lies partially within the limits of the prehispanic city, based on the recovery during surface survey of Tollan complex ceramics from its western slope. In 2007, the Ejido Huerto de Natzha, a tract of land approximately 110 × 160 meters on the south slope of Cerro Magoni, was created for agricultural development (Figure 20). The tract was subdivided into 25 plots, each requiring archaeological intervention before undergoing development, which in most cases involved exploratory excavation, using 2 × 2 m pits oriented to the boundaries of the overall tract. Most of the excavations yielded prehispanic artifacts, often in abundance, and structural remains were encountered that led to more extensive excavations in seven plots (Figures 20a–20g).

Figure 20. Topographic map of the Huerto de Natzha locality on the southern slope of Cerro Magoni (inset). (a–e) Location and architectural remains encountered in archaeological excavation; (h) in profile in a modern cut, at a common scale. Maps and plan drawings by Healan and Gamboa Cabezas.

Despite considerable damage from erosion, five of the extensive excavations encountered structural remains that appear to represent residential compounds composed of one or more structures (Figures 20a–20e). The other two excavations exposed portions of retaining walls (Figures 20f–20g), presumably constructed to level portions of the hill slope for habitation. The excavation farthest up the slope (Figure 20a) exposed a portion of a small altar faced with tabular stone and covered with stucco, a common feature of patios in residential compounds at Tula. Remnants of stucco flooring were encountered in some of the structures, and there was evidence of variability in architectural quality, as seen in other localities. Of particular interest is a structural complex that was largely destroyed by illegal modern construction, but visible in a cut whose profiles revealed superposed stucco-covered floors and adobe walls of what appear to be a series of high-status residences (Figure 20h).