According to the American Psychiatric Association's practice guideline, the primary treatment for borderline personality disorder is psychotherapy, complemented by symptom-targeted pharmacotherapy if necessary (American Psychiatric Association, 2001). It is stated in this guideline that two psychotherapeutic approaches have been shown in randomised trials to have efficacy: psychoanalytic/psychodynamic therapy and dialectical behaviour therapy. The guideline has been criticised because it is primarily based upon evidence from uncontrolled or single case studies and clinical consensus (e.g. Reference TyrerTyrer, 2002). Only few methodologically rigorous efficacy studies have been conducted. With respect to dialectical behaviour therapy, two randomised clinical trials of small to moderate size have been conducted (Linehan et al, Reference Linehan, Armstrong and Suarez1991, Reference Linehan, Schmidt and Dimeff1999a ). In addition, several other unpublished or uncontrolled studies have been summarised by Koerner & Linehan (Reference Koerner and Linehan2000).

In a randomised controlled trial, we compared the effectiveness of dialectical behaviour therapy with treatment as usual in terms of the therapy's primary targets (Reference Linehan, Kanter, Comtois and JanowskyLinehan et al, 1999b ): first, treatment retention and second, high-risk behaviours, including suicidal, self-mutilating and self-damaging impulsive behaviours. A further aim was to examine whether the efficacy of dialectical behaviour therapy is modified by baseline severity of parasuicide. This report describes the first 12 months of the trial.

METHOD

Sample recruitment

Women with borderline personality disorder aged 18-70 years residing within a 40-km circle centred on Amsterdam, who were referred by a psychologist or psychiatrist willing to sign an agreement expressing the commitment to deliver 12 months of treatment as usual, were considered for recruitment. No restriction was made in terms of the referral source. Referrals originated from addiction treatment services, psychiatric hospitals, centres for mental health care, independently working psychologists and psychiatrists, and even from general practitioners and self-referral. Women in the latter two categories were allowed to participate in the study only when they were able to locate a psychologist or psychiatrist willing to provide treatment as usual. The exclusion criteria were a DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar disorder or (chronic) psychotic disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), insufficient command of the Dutch language, and severe cognitive impairments. The diagnosis of borderline personality disorder was established using both the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire, DSM-IV version (Reference HylerHyler, 1994) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders (SCID-II; Reference First, Spitzer and GibbonFirst et al, 1994). Positive endorsement of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder was required on both instruments. In contrast to Linehan's trial (Reference Linehan, Armstrong and SuarezLinehan et al, 1991), the sample consisted primarily of clinical referrals from both addiction treatment and psychiatric services, and participants were not required to have shown recent parasuicidal behaviour.

Randomisation procedure

Following the completion of the intake assessments, patients were randomly assigned to treatment conditions. A minimisation method was used to ensure comparability of the two treatment conditions on age, alcohol problems, drug problems and social problems (as measured by the European version of the Addiction Severity Index (Reference Kokkevi and HartgersKokkevi & Hartgers, 1995)).

Treatments

Patients assigned to dialectical behaviour therapy received 12 months of treatment as specified in the manual (Reference LinehanLinehan, 1993). The treatment combines weekly individual cognitive—behavioural psychotherapy sessions with the primary therapist, weekly skills-training groups lasting 2-2.5 h per session, and weekly supervision and consultation meetings for the therapists (Reference LinehanLinehan, 1993). Individual therapy focuses primarily on motivational issues, including the motivation to stay alive and to stay in treatment. Group therapy teaches self-regulation and change skills, and skills for self-acceptance and acceptance of others. Among its central principles is dialectical behaviour therapy's simultaneous focus on both acceptance and validation strategies and change strategies to achieve a synthetic (dialectical) balance in client functioning. The median adherence score on a 5-point Likert scale was 3.8 (range 2.5-4.5), indicating ‘almost good dialectical behaviour therapy’ in terms of conformity to the treatment manual.

‘Treatment as usual’ consisted of clinical management from the original referral source (addiction treatment centres n=11, psychiatric services n=20). Patients in this group attended generally no more than two sessions per month with a psychologist, a psychiatrist or a social worker.

Therapists

Extensive attention was paid to the selection, training and supervision of the dialectical behaviour therapists, who included four psychiatrists and 12 clinical psychologists. Group training was conducted in three separate groups led jointly by social workers and clinical psychologists. Training, regular monitoring (using videotapes) and weekly individual and group supervision were performed by the second author (L.M.C.B.), who received intensive training from Professor Linehan in Seattle and is a member of the international dialectical behaviour therapy training group.

Outcome assessments

Baseline assessments took place 1-16 weeks (median 6 weeks) before randomisation. Therapy began 4 weeks after randomisation. Three clinical psychologists (two with master's degrees and one a Doctor of Philosophy) conducted all assessments. They were experienced diagnosticians who received additional specific training in the administration of the instruments.

Recurrent parasuicidal and self-damaging impulsive behaviours were measured at baseline and at 11, 22, 33, 44 and 52 weeks after randomisation using the appropriate sections of the Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index (BPDSI; Reference Arntz, Hoorn and van den CornelisArntz et al, 2003), a semi-structured interview assessing the frequency of border-line symptoms in the previous 3-month period. The BPDSI consists of nine sections, one for each of the DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder. The parasuicide section includes three items reflecting distinct suicidal behaviours (suicide threats, preparations for suicide attempts, and actual suicide attempts). The impulsivity section includes 11 items reflecting the manifestations of self-damaging impulsivity (e.g. gambling, binge eating, substance misuse, reckless driving). The parasuicide and impulsivity sections have shown reasonable internal consistencies (0.69 and 0.67, respectively), excellent interrater reliability (0.95 and 0.97, respectively) and good concurrent validity (Reference Arntz, Hoorn and van den CornelisArntz et al, 2003). Three month test—retest reliability for the total BPDSI score was 0.77.

Self-mutilating behaviours were measured using the Lifetime Parasuicide Count (LPC; Reference Comtois and LinehanComtois & Linehan, 1999) at baseline and the adapted (3-month) version was administered 22 weeks and 52 weeks after randomisation. The LPC obtains information about the frequency and subsequent medical treatment of self-mutilating behaviours (e.g. cutting, burning and pricking).

Completeness of data

Of the five follow-up assessments, participants completed a mean of 3.7 assessments, with no significant difference between treatment conditions (Cochran—Mantel—Haenszel test χ2 3=1.51; P=0.14). Forty-seven (81%) completed the assessment at week 52.

Statistical analysis

For the analysis of treatment retention, chisquared analysis was used. The course of high-risk behaviours as measured with the LPC and BPDSI was analysed using a general linear mixed model (GLMM) approach (‘Mixed’ procedure from SAS version 6.12; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Preliminary to the GLMM analyses, examination of the variable characteristics revealed highly skewed distributions of the BPDSI parasuicide and impulsivity and the LPC total score. A shifted log transformation was performed on each of these variables. A Bonferroni correction to the level of significance was applied, resulting in an α of 0.013 (0.05/4).

Within the GLMM approach, we used a two-step procedure: first, the covariance structure was fitted using restricted likelihood and a saturated fixed model, and second the fixed model was refined using maximum likelihood (Reference Verbeke and MolenberghsVerbeke & Molenberghs, 1997). The main advantage of the GLMM approach over standard repeated-measurement multivariate analysis of variance is that it allows for inclusion of cases with missing values, thereby providing a better estimate of the true (unbiased) effect within the intention-to-treat sample. To examine the effect of dialectical behaviour therapy on the course of high-risk behaviours, we used a model with time, treatment, and time × treatment interaction. To correct for possible initial differences, baseline severity was added as a covariate. To examine the impact of initial severity on outcome, we implemented a model with time, baseline severity, treatment condition and the two-way and three-way interactions between these variables.

RESULTS

Recruitment and patient characteristics

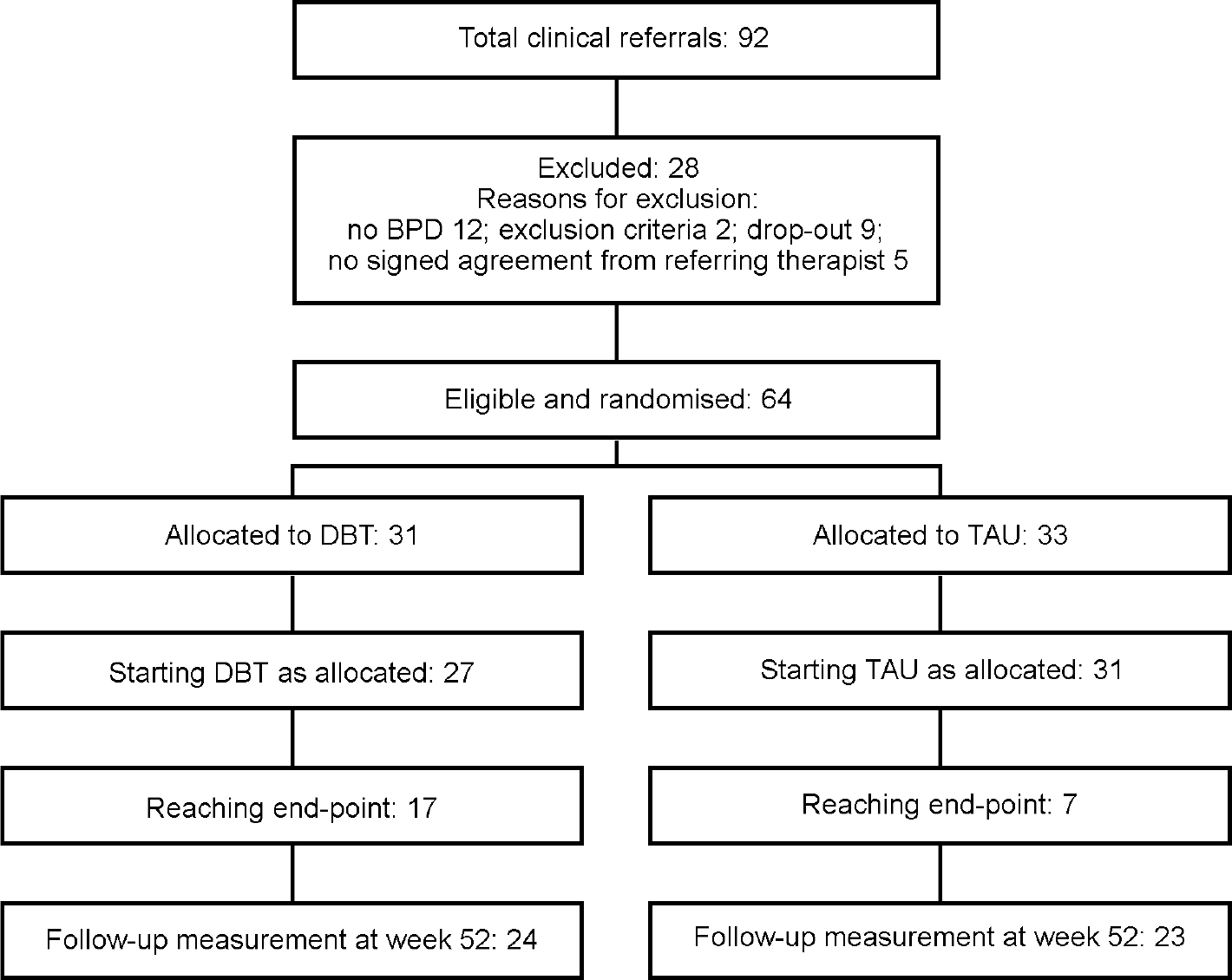

Of the 92 patients referred to and considered for this study, 64 were eligible and gave written informed consent. Thirty-one were assigned to dialectical behaviour therapy and 33 to treatment as usual. Two patients assigned to the treatment-as-usual condition were dropped from the intention-to-treat analyses because they did not accept the randomisation outcome and therefore refused to cooperate further with the study protocol, and four patients assigned to dialectical behaviour therapy were dropped because they refused to start treatment. Flow through the study and the main reasons for exclusion are shown in Fig. 1. Severity of borderline personality disorder, addiction severity and age were not significantly associated with attrition between the intake phase and inclusion in the intention-to-treat sample. There was no significant difference between treatment conditions on socio- demographic variables, number of DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder met, history of suicide attempts, number of self-mutilating acts, or prevalence of clinically significant alcohol and/or drug use problems (Table 1).

Fig. 1 Recruitment and attrition of study participants. BPD, borderline personality disorder; DBT, dialectical behaviour therapy; TAU, treatment as usual.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants

| Characteristic | Treatment group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| DBT (n=27) | TAU (n=31) | Total | |

| Dutch nationality, n (%) | 26 (96) | 30 (97) | 56 (97) |

| Never married, n (%) | 15 (56) | 21 (68) | 36 (62) |

| Living alone, n (%) | 9 (33) | 12 (39) | 21 (36) |

| Unemployed, n (%) | 7 (26) | 5 (16) | 12 (21) |

| Disability pension, n (%) | 15 (56) | 19 (61) | 34 (59) |

| Age (years), mean (s.d.) | 35.1 (8.2) | 34.7 (7.4) | 34.9 (7.7) |

| Education (years), mean (s.d.) | 12.6 (3.3) | 13.6 (3.8) | 13.1 (3.6) |

| Number of BPD criteria, mean (s.d.)1 | 7.3 (1.3) | 7.3 (1.3) | 7.3 (1.3) |

| History of suicide attempts, n (%)2 | 19 (70) | 22 (71) | 41 (71) |

| History of self-mutilation, n (%)3 | 25 (93) | 29 (94) | 54 (93) |

| Lifetime self-mutilating acts, median3 | 13.1 | 14.4 | 14.2 |

| Addictive problems, n (%)2 | 16 (59) | 16 (52) | 32 (55) |

Treatment retention

Significantly more patients who were receiving dialectical behaviour therapy (n=17; 63%) than patients in the control group (n=7; 23%) continued in therapy with the same therapist for the entire year (χ2 1=9.70; P=0.002). This difference was maintained when two members of the control group who were assigned to other therapists within the same institutes were included in the calculation (χ2 1=6.72; P=0.010).

High-risk behaviours

The frequency and course of suicidal behaviours were not significantly different across treatment conditions: neither treatment condition (t 1,137=0.03; P=0.866) nor the interaction between time and treatment condition (t 1,166=0.22; P=0.639) reached statistical significance. An additional analysis revealed that, although fewer patients in the dialectical behaviour therapy group (n=2; 7%) than in the control group (n=8; 26%) attempted suicide during the year, this difference was not statistically significant (χ2 1=3.24; P=0.064).

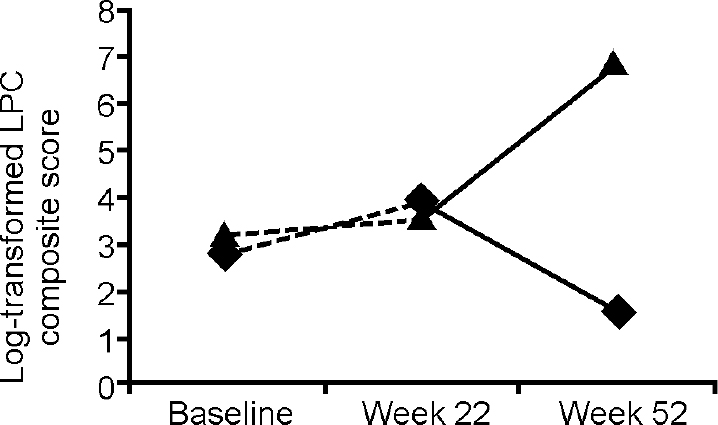

Self-mutilating behaviours of patients assigned to dialectical behaviour therapy gradually diminished over the treatment year, whereas patients assigned to treatment as usual gradually deteriorated in this respect: a significant effect was observed for the interaction term time × treatment condition (t 1,44.4=10.24; P=0.003) but not for treatment condition alone (t 1,69.1=3.80; P=0.055) (Fig. 2). The most frequently reported self-mutilating acts were cutting, burning, pricking and head-banging. At the week 52 assessment, 57% (n=13) of the treatment-as-usual patients reported engaging in any self-mutilating behaviour at least once in the previous 6-month period (median 13 times), against 35% (n=8) of the dialectical behaviour therapy group (median 1.5 times); median test χ2 1=4.02; P=0.045.

Fig. 2 Frequency of self-mutilating behaviours in the previous 3 months at week 22 and week 52 from the start of treatment with dialectical behaviour therapy (♦) (n=27) or treatment as usual (▴) (n=31). LPC, Lifetime Parasuicide Count.

In terms of self-damaging impulsive behaviour, patients assigned to dialectical behaviour therapy showed more improvement over time than patients in the control group: a significant effect was evident for the interaction term time × treatment condition (t 1,164=2.60; P=0.010) but not for treatment condition alone (t 1,122=1.02; P=0.315) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Frequency of self-damaging impulsive acts in the previous 3 months at weeks 11, 22, 33, 44 and 52 from the start of treatment with dialectical behaviour therapy (♦) (n=27) or treatment as usual (▴) (n=31). BPDSI, Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index.

Confounding by medication use

Medication use was monitored by administration of the Treatment History Interview (Reference Linehan and HeardLinehan & Heard, 1987) at weeks 22 and 52. The greater improvement in the dialectical behaviour therapy group could not be explained by greater or other use of psychotropic medications by these patients. In both conditions, three-quarters of the patients reported use of medication from one or more of the following categories: benzodiazepines, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, mood stabilisers and neuroleptics. Use of SSRIs was reported by 14 (52%) of the dialectical behaviour therapy patients and 19 (61%) of treatment-as-usual patients (χ2 1=0.44; P=0.509). These findings eliminate the possibility of confounding by medication use.

Impact of baseline severity on effectiveness

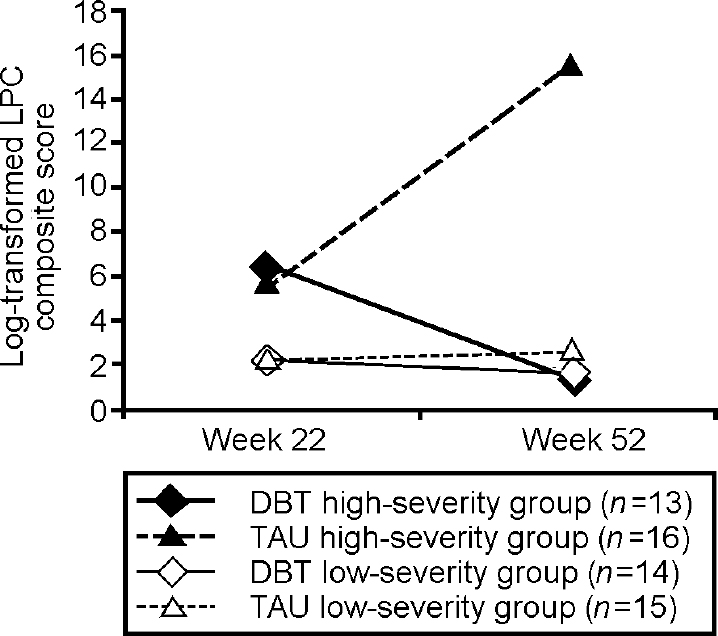

The sample was divided according to a median split on the lifetime number of self-mutilating acts. The number in the lower-severity group ranged from 0 to 14 (median 4.0) and in the higher-severity group from 14 to more than 1000 (median 60.5). The two groups did not differ with respect to the total score on the BPDSI and the Addiction Severity Index. For suicidal behaviour an almost significant effect was evident for the three-way interaction term time × severity × treatment condition (t 1,170=4.81; P=0.029), indicating a trend towards greater effectiveness of dialectical behaviour therapy in severely affected individuals. For self-mutilating behaviours a significant effect was evident for the three-way interaction term time × severity × treatment condition (t 1,404=16.82; P=0.000) and the interaction term severity × treatment condition (t 1,67.6=9.63; P=0.003), indicating that dialectical behaviour therapy was superior to treatment as usual for patients in the high-severity group but not for their low-severity counterparts (Fig. 4). No differential effectiveness was found for self-damaging impulsivity.

Fig. 4 Frequency of self-mutilating behaviour in the previous 3 months at week 22 and week 52 from the start of treatment, analysed according to treatment condition and baseline severity. Membership of severity group is determined by the median split on the lifetime number of self-mutilating acts (<14 v. ≥14). DBT, dialectical behaviour therapy; LPC, Lifetime Parasuicide Count; TAU, treatment as usual.

DISCUSSION

Summary of findings

This randomised controlled trial of dialectical behaviour therapy yielded three major results. First, dialectical behaviour therapy had a substantially lower 12-month attrition rate (37%) compared with treatment as usual (77%). Second, it resulted in greater reductions in self-mutilating behaviours and self-damaging impulsive acts than treatment as usual. Importantly, the greater impact of dialectical behaviour therapy could not be explained by differences between the treatment groups in the use of psychotropic medications. Finally, the beneficial impact on the frequency of self-mutilating behaviours was far more pronounced in participants who reported higher baseline frequencies than in those reporting lower baseline frequencies.

Significance of findings

The current study results — being highly concordant with previously published studies — are significant for several reasons. First, this is the first clinical trial of dialectical behaviour therapy that was not conducted by its developer and that was conducted outside the USA. This study supports the accumulating evidence that mental health professionals outside academic research centres can effectively learn and apply dialectical behaviour therapy (Reference Hawkins and SinhaHawkins & Sinha, 1998), and that the therapy can be successfully disseminated in other settings (Reference Barley, Buie and PetersonBarley et al, 1993; Reference Springer, Lohr and BuchtelSpringer et al, 1996) and in other countries. Second, a relatively large sample size allowed more rigorous statistical testing of the therapy's efficacy than former trials, thereby countering some of the recently expressed concerns about the status of dialectical behaviour therapy as the treatment of choice for borderline personality disorder (Reference ScheelScheel, 2000; Reference TyrerTyrer, 2002). Third, our findings indicated that patients receiving treatment as usual deteriorated over time, suggesting that non-specialised treatment facilities might actually cause harm rather than improvement. Finally, in contrast to the original trial (Reference Linehan, Armstrong and SuarezLinehan et al, 1991), the sample was drawn from clinical referrals from both addiction treatment and psychiatric services, and people with substance use disorders were not excluded. Our study provides evidence that standard dialectical behaviour therapy is suitable for patients with borderline personality disorder regardless of the presence of substance use disorders (cf. Reference Bosch, Verheul and SchippersBosch et al, 2002). This is consistent with a previous report showing that, in borderline personality disorder, patients with substance use disorders are largely similar to those without such disorders in terms of type and severity of symptoms, treatment history, family history of substance use disorders and adverse childhood experiences (Reference Bosch, Verheul and BrinkBosch et al, 2001). Together these findings imply that addictive behaviours in patients with borderline personality disorder can best be considered as a manifestation of the borderline disorder rather than as a condition that constitutes significant clinical heterogeneity and justifies the exclusion of these patients from efficacy studies.

Clinical implications

Based upon multiple effectiveness studies, it is now well established that dialectical behaviour therapy is an efficacious treatment of high-risk behaviours in patients with borderline personality disorder. This is probably due to some of this treatment's distinguishing features:

-

(a) routine monitoring of the risk of these behaviours throughout the treatment programme;

-

(b) an explicit focus on the modification of these behaviours in the first stage of treatment;

-

(c) encouragement of patients to consult therapists by telephone before carrying out these behaviours;

-

(d) prevention of therapist burnout through frequent supervision and consultation group meetings (Reference LinehanLinehan, 1993).

Across studies, however, dialectical behaviour therapy has not been effective in reducing depression and hopelessness, or in improving survival and coping beliefs or overall life satisfaction (Reference ScheelScheel, 2000). In addition, our study showed that, although dialectical behaviour therapy was effective in reducing self-harm in chronically parasuicidal patients, its impact on patients in the low-severity group was similar to that of treatment as usual. Together, these findings suggest that dialectical behaviour therapy should — consistent with its original aims (Reference LinehanLinehan, 1987) — be the treatment of choice only for patients with borderline personality disorder who are chronically parasuicidal and should perhaps be extended or followed by another treatment, focusing on other components of the borderline personality disorder, as soon as the level of high-risk behaviour is sufficiently reduced. Alternatively, it could be argued that dialectical behaviour therapy is the treatment of choice for patients with severe, life-threatening impulse-control disorders rather than borderline personality disorder per se, implying that patients with other severe impulse-regulation disorders (e.g. substance use disorders or eating disorders) might benefit from the therapy. The latter interpretation is consistent with the development of modified versions of dialectical behaviour therapy for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder and a comorbid diagnosis of drug dependence (Reference Linehan, Schmidt and DimeffLinehan et al, 1999a ), or patients with a binge eating disorder (Reference Wiser and TelchWiser & Telch, 1999).

Limitations

One limitation of our study is that dialectical behaviour therapy was compared with treatment as usual or unstructured clinical management. This has been recommended as a first step in establishing the efficacy of a treatment (Reference Teasdale, Fennell and HibbertTeasdale et al, 1984; Reference Linehan, Armstrong and SuarezLinehan et al, 1991), but it allows no conclusion about the effect of the experimental treatment compared with other manual-based treatment programmes.

The observed effect size of dialectical behaviour therapy might be different from the true effect size because of a number of factors. First, although the research assessors were not informed about the treatment condition of their interviewees, it is unlikely that they remained ‘masked’ throughout the project. Patients might have given them this information, or it could easily have been derived from some of the interviews. This concern is somewhat mitigated by the fact that the research focused on objective behaviours rather than subjective perceptions and experiences. Second, it is important to note that an effect of dialectical behaviour therapy was observed in spite of the potentially equalising impact of the attention paid to patients by the research assessors during multiple repeated measurements, including the substantial efforts made to contact patients for appointments. Third, because we selected patients in ongoing therapy who were willing to terminate the treatment, some of the patients might have perceived assignment to treatment as usual to be a less desirable randomisation outcome than assignment to dialectical behaviour therapy. Finally, the observed effect might be biased by a possible Hawthorne effect in terms of greater enthusiasm among the dialectical behaviour therapists compared with those providing conventional therapy.

Although the latter two factors could have favoured dialectical behaviour therapy in terms of patient satisfaction or the quality of the working alliance, additional analyses revealed that the two patient groups were highly similar in terms of scores on the three sub-scales of the Working Alliance Inventory (Reference Horvath and GreenbergHorvath & Greenberg, 1989): development of bond, agreement on goals and agreement on tasks. This observed similarity is striking since the quality of the working alliance is often considered to be a prerequisite of efficacy in psychotherapy (e.g. Reference Lambert, Bergin, Bergin and GarfieldLambert & Bergin, 1994) and because a substantial feature of dialectical behaviour therapy is the establishment of a working alliance (Reference LinehanLinehan, 1993). Perhaps the efficacy of dialectical behaviour therapy results from the persistent and enduring focus on certain target behaviours rather than an ‘optimal’ working alliance.

Further directions

The participants in this study were followed up after 18 months to examine whether the treatment results were maintained after discharge. The results will be published elsewhere. Future research should focus on comparison with concurrent therapies such as schema-focused cognitive therapy (Reference YoungYoung, 1990) and psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalisation (Reference Bateman and FonagyBateman & Fonagy, 2001), as well as on the effective mechanisms at work. Potential mediators of favourable outcomes are, for example, reduced catastrophising, enhanced skills for regulating affect and coping with life events, or an increase in reasons for living (Reference Rietdijk, Verheul and BoschRietdijk et al, 2001). Knowledge about the specific mechanisms that make dialectical behavior therapy work might enable therapists to better direct the focus in treatment, and possibly stimulate dismantling studies to investigate the efficacy of the individual components of the therapy.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) is an efficacious treatment of high-risk behaviours in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD). Evidence suggests that DBT should be followed by another treatment focusing on other components of BPD, as soon as the high-risk behaviours are sufficiently reduced.

-

▪ Mental health professionals outside academic research centres can effectively learn and apply DBT, and it can be successfully disseminated in other settings and other countries.

-

▪ Dialectical behaviour therapy may be a treatment of choice for patients with severe, life-threatening impulse control disorders rather than for BPD per se. There is a lack of evidence that DBT is efficacious for other core features of BPD, such as interpersonal instability, chronic feelings of emptiness and boredom, and identity disturbance.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Although the research assessors were not informed about the treatment condition of their interviewees, it is unlikely that they remained ‘masked’ throughout the project.

-

▪ Comparing DBT with treatment as usual allows no conclusion about the efficacy of DBT relative to other manual-based treatment programmes.

-

▪ The observed effect might be biased by greater enthusiasm among the dialectical behaviour therapists, although DBT was not superior in terms of patient-reported working alliance.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Eveline Rietdijk and Wijnand van der Vlist in collecting the data.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.