Introduction

The institutional basis for sustainable common-pool resource governance has long been a subject of intense scholarly discourse. While there are no institutional panaceas for achieving sustainable resource governance (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2007), institutional perspectives on sustainable common-pool resource governance have evolved from a focus on state-led (centralization) and market-based (privatization) governance mechanisms (Gordon, Reference Gordon1954; Hardin, Reference Hardin1968) to common-property regimes and hybrid institutional arrangements such as co-management regimes (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Degnbol, Viswanathan, Ahmed, Hara and Abdullah2004; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990). Since the early 1990s, many institutional economists have espoused the sustainability potential of participatory and community-based resource management regimes (e.g. Baland and Platteau Reference Baland and Platteau1996; Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990; Wade Reference Wade1987). Co-management regimes – hybrid institutional arrangements in which power, decision-making rights, and responsibilities over resource management are shared, usually between state-level actors and resource users (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Degnbol, Viswanathan, Ahmed, Hara and Abdullah2004) – have since become mainstream and the preferred institutional regimes for the governance of marine and coastal resources (Cinner et al., Reference Cinner, Daw, McClanahan, Muthiga, Abunge, Hamed, Mwaka, Rabearisoa, Wamukota, Fisher and Jiddawi2012).

Co-management is often argued to have the potential to achieve sustainable resource governance for both normative and efficiency reasons: user participation in governance enhances legitimacy and compliance, reduces ex-post transaction costs, and improves resource management outcomes (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Degnbol, Viswanathan, Ahmed, Hara and Abdullah2004). However, in the wave of institutional changes towards co-management regimes in marine and coastal resource systems in many countries, sustainable resource governance outcomes have not been monolithic. The corpus of existing co-management literature examined the social, economic, and ecological outcomes of such institutional regimes in coastal fisheries, revealing varying degrees of success (see Cinner and McClanahan Reference Cinner and McClanahan2015; d'Armengol et al., Reference d'Armengol, Prieto Castillo, Ruiz-Mallén and Corbera2018; Gelcich et al., Reference Gelcich, Hughes, Olsson, Folke, Defeo, Fernández, Foale, Gunderson, Rodríguez-Sickert, Scheffer, Steneck and Castilla2010). However, the implementation process, effectiveness, and sustainability of co-management regimes have faced challenges in many countries (Hara and Nielsen, Reference Hara, Nielsen, Wilson, Nielsen and Degnbol2003; Levine, Reference Levine2016; Nunan, Reference Nunan2020). Extant literature attributes challenges to factors such as lack of participation, unclear definition of roles among stakeholders, weak social capital, power struggles, institutional incapacity, and unsustainable funding mechanisms (Levine, Reference Levine2016; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Degnbol, Viswanathan, Ahmed, Hara and Abdullah2004; Njaya et al., Reference Njaya, Donda and Béné2012; Nunan et al., Reference Nunan, Hara and Onyango2015).

Yet, there is still a gap in our understanding of why co-management regimes succeed in some countries but fail in other contexts. Promising avenues for probing contextual conditions relate to the political-economic, socio-cultural, and ideational dynamics of resource governance context (Clement and Amezaga, Reference Clement and Amezaga2013), which have until now been underresearched (however, see Etiegni et al., Reference Etiegni, Irvine and Kooy2017; Nunan Reference Nunan2020; Nunan et al., Reference Nunan, Hara and Onyango2015; Russell and Dobson Reference Russell and Dobson2011). Drawing from critical institutionalism (Cleaver, Reference Cleaver2012; Cleaver and De Koning, Reference Cleaver and De Koning2015), extant studies suggest that the nature of interactions between formal and informal institutions and how co-management is designed to fit socially embedded institutions can hinder the effectiveness and resilience of co-management regimes (Nunan et al., Reference Nunan, Hara and Onyango2015). However, it is unclear if and to what extent the processes and mechanisms that produce the development and implementation of co-management arrangements may influence institutional interactions that facilitate or hinder the effectiveness and sustainability of co-management regimes. While some studies have examined the process of transitions to co-management regimes in marine and coastal resource governance (Cinner et al., Reference Cinner, Daw, McClanahan, Muthiga, Abunge, Hamed, Mwaka, Rabearisoa, Wamukota, Fisher and Jiddawi2012; Gelcich et al., Reference Gelcich, Hughes, Olsson, Folke, Defeo, Fernández, Foale, Gunderson, Rodríguez-Sickert, Scheffer, Steneck and Castilla2010; Ho et al., Reference Ho, Ross and Coutts2016), most co-management literature has focused on explaining the socioeconomic and ecological outcomes of co-management without probing the causal mechanisms that link the drivers of institutional change to the effectiveness and sustainability of the resultant institutional arrangements. This study contributes to this perspective by examining the role of ideology and contextual institutional histories in the challenges of developing and sustaining co-management arrangements for coastal fisheries in Ghana.

Ghana is an ideal context to examine because of its long history of traditional fisheries governance and unsuccessful experiences in establishing a formal coastal fisheries co-management regime. In the late 1990s, a process of institutional change was initiated in coastal fisheries, leading to the development of co-management structures across the coast. However, this institutional arrangement was ineffective and could not be sustained, and most of the governance structures collapsed a few years after the project ended (Finegold et al., Reference Finegold, Gordon, Mills, Curtis and Pulis2010). The main goal of this study is to understand if and to what extent the failure of the coastal resource co-management regime is linked to the contextual dynamics of the institutional change process. The study thus examines the following questions: why and how was co-management institutionalized in coastal fisheries? What role did ideology and contextual institutional histories play in the practice and outcomes of the co-management regime? This paper explores these questions through a process-tracing approach, drawing from the perspectives of legal pluralism and ideational theories of institutional change. By adopting process tracing – an in-depth qualitative case study methodology that seeks to explain historical outcomes by unpacking causal mechanisms linking the drivers of institutional and policy changes and the outcomes of those changes (Beach, Reference Beach, Wagemann, Goerres and Siewert2018) – this study brings analytical attention to the study of processes that connect the underlying drivers of institutional development to the outcomes of co-management arrangements.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. The next section outlines the theoretical perspectives and potential causal mechanisms of the transition to co-management regimes. This provides a framework for empirically tracing the emergence of co-management in Ghana. Section ‘Materials and methods’ elaborates on the research methods. Section ‘Results and analysis’ presents the analysis, starting with the contextual scope conditions and then tracing the causal process of the transition to the co-management regime. A reflection on the role of ideology and legal pluralism in the failure of the co-management regime is also offered, leading to conclusions in section ‘Conclusions’.

Theorizing causal mechanisms of institutional transformation to co-management regimes

The literature on resource governance evolutions to co-management regimes emphasizes the role of socioeconomic, ecological, and political drivers of change. Some common causal mechanisms of transition to co-management regimes in marine coastal systems include resource use conflicts, resource depletion/crisis, major sociopolitical changes, changes in market dynamics, and ideational change/ideological diffusion (Cinner et al., Reference Cinner, Daw, McClanahan, Muthiga, Abunge, Hamed, Mwaka, Rabearisoa, Wamukota, Fisher and Jiddawi2012; Gelcich et al., Reference Gelcich, Hughes, Olsson, Folke, Defeo, Fernández, Foale, Gunderson, Rodríguez-Sickert, Scheffer, Steneck and Castilla2010; Orach and Schlüter, Reference Orach and Schlüter2021). In many coastal resource systems, especially in developing countries, the transition to co-management regimes has often been triggered by international donor pressure and ideological diffusion mechanisms through international development organizations such as the World Bank, international non-governmental organizations, and foreign government agencies (Cinner et al., Reference Cinner, Daw, McClanahan, Muthiga, Abunge, Hamed, Mwaka, Rabearisoa, Wamukota, Fisher and Jiddawi2012; Hara and Nielsen, Reference Hara, Nielsen, Wilson, Nielsen and Degnbol2003; Ho et al., Reference Ho, Ross and Coutts2016; Orach and Schlüter, Reference Orach and Schlüter2021). This paper unpacks the ideational change/diffusion causal mechanism (see Figure 1) because the institutional transformation to co-management was externally induced. To achieve this, the article draws on the ideational theory of institutional change to develop the relevant parts of the causal mechanism. The ideational theory of institutional change is complemented with the analytical perspectives of legal pluralism to examine the role of contextual scope conditions that influence the instantiation of the causal mechanism for the governance transformation. This is important for examining the role of the broader institutional environment in hindering the transition to co-management regimes in Ghanaian coastal fisheries. Despite the usefulness of legal pluralism for institutional analysis in resource governance, its link with theories of institutional change has not yet been explicitly illuminated in empirical studies of institutional change in coastal resource governance. This study leverages the complementary value of these theoretical perspectives to understand the process and outcomes of common-pool resource governance transformation.

Figure 1. Conceptualized ideational change mechanism in the transformation to a coastal resource co-management regime.

Ideational theories of institutional change

Numerous theories of institutional change exist in institutional economics, as comprehensively reviewed in the literature (see Banikoi et al., Reference Banikoi, Schlüter and Manlosa2023; Kingston and Caballero Reference Kingston and Caballero2009). Conventional economics explanation of institutional change often emphasizes the efficiency function of institutions whereby, through competition, institutional alternatives that minimize transaction costs and optimize outcomes will emerge to govern economic exchange. However, Denzau and North (Reference Denzau and North1994) argue that in contexts of high uncertainty and complexity, it is impossible to rationally calculate the ex-ante costs and benefits of institutional alternatives; thus, actors rely on mental models and ideologies for institutional choice. Ideologies here refer to ‘the shared framework of mental models that groups of individuals possess that provide both an interpretation of the environment and a prescription as to how that environment should be structured’ (Denzau and North, Reference Denzau and North1994: 4). Ideologies have cognitive (help in interpreting environment), normative (define what is right), programmatic (condition one to act in a certain way) and solidary (instigate one to act in solidarity with others) dimensions (Higgs, Reference Higgs2008). Ideologies are the underlying logical structure of institutions in a society; a change in ideologies may thus trigger a co-evolutionary change in institutions (Sauerland, Reference Sauerland2015).

Ideational theories thus view institutional change as resulting from people interpreting their world in various ways through ideational elements, and how ideational change and ideational resources can influence actors’ normative and cognitive beliefs about institutions (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004; Denzau and North, Reference Denzau and North1994; North, Reference North2005). Campbell (Reference Campbell2004) identified four typologies of cognitive and normative ideas that influence institutional change: paradigms (background assumptions or mental models that constrain the cognitive range of useful programs), programs (prescriptions that enable actors to chart a particular path of institutional change); frames (discourses, narratives, and symbol actors use to legitimize programs or institutions); and public sentiments (public assumptions that constrain the normative range of legitimate programs available to actors). Ideational elements can change through actors learning from their internal environment and culture (North, Reference North2005), but they can also be shaped by exogenous discourses and ideas (Higgs, Reference Higgs2008). Ideological change can be theory-driven, where influential academic scholarship changes worldviews and paradigms, or event-driven, whereby events such as crises can provide opportunities for ideological change through the supply of ideas (Higgs, Reference Higgs2008). Change in ideologies may also result from logical incoherencies, which ideational entrepreneurs can leverage to develop new and less sophisticated but more logically coherent and consistent competing ideologies to cause a shift in ideologies and, hence, trigger institutional change (Sauerland, Reference Sauerland2015: 570).

Ideas do not often emerge and proliferate spontaneously; the role of ideational brokers is crucial for ideational change in one ideational realm to influence institutional change in another realm (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004). In a transnational diffusion of new ideas, ideational brokers could be individual actors, epistemic communities, or international organizations who broker the flow of these ideas to actively influence ideational and institutional change at the national level through various diffusion mechanisms. Such mechanisms include competition (adopting ideas to match competitors), mimicry (imitation to enhance performance), learning (normative adoption to enhance legitimacy), and coercion (imposition of ideas by powerful actors in exchange for loans and valuable resources) (Campbell, Reference Campbell, Morgan, Campbell, Crouch, Pedersen and Whitley2010; DiMaggio and Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983). The coercion mechanism can also be subtle in the sense that ideational elements may be adopted to gain the support of the originator (DiMaggio and Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983). The diffused ideas can be institutionalized through the mechanism of translation (blending of institutional principles with existing institutional arrangements) or bricolage (the innovative process of assembling and recombining existing institutional repertoire to create new institutional arrangements) (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004). This brings to the fore the challenge of potential ideological conflicts in the institutionalization of ideational change in the context of legal pluralism, such as coastal fisheries, as ideologies are the underlying logical structure of social institutions (Sauerland, Reference Sauerland2015). Although this ideational perspective has not been used extensively in studying coastal resource governance outcomes, it provides a useful complementary theoretical lens for studying the process of institutional change and governance outcomes in the context of legal pluralism.

Legal pluralism and institutional change

Coastal resource governance is a realm in which legal pluralism is ubiquitous, and its analytical perspectives have been adopted to study governance outcomes (Bavinck and Gupta, Reference Bavinck and Gupta2014; Jentoft et al., Reference Jentoft, Bavinck, Johnson and Thomson2009). Legal pluralism denotes the situation where ‘within the same social order, or social or geographical space, more than one body of law, pertaining to more or less the same set of activities, may co-exist. Rules and principles generated and used by the state organization appear as one variation besides law generated and maintained by other organizations and authorities with different sources of legitimations such as religion or tradition’ (von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann, Reference von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann2006: 14). In resource governance, legal pluralism as an analytical concept denotes multiple legal systems – rules, norms, practices, regulations, and their associated enforcement and decision-making authorities – with different sources of legitimation structure human-environment interactions. The mode of institutional interaction or relationship between legal systems in resource governance is termed a ‘governance pattern’. Such governance patterns are conceptualized to include four ideal types: indifference, competition, accommodation, and mutual support (Bavinck and Gupta, Reference Bavinck and Gupta2014). Indifference refers to a situation where the two legal systems operate in parallel without operational overlap (e.g., if rules emanating from the national legal system are not implemented in coastal fisheries while the customary legal system continues to operate).

Competition occurs where there is a strong and contrary relationship between the legal systems, and they compete for power to govern the same jurisdiction or situation (e.g., national regulations and customary rules compete to govern coastal fisheries). In accommodation, the legal systems interact non-conflictual, and there is a recognition of each other's legitimacy and a measure of reciprocal adaptation but little formal institutional or jurisdictional integration. In the mutual support type, there is a formal recognition of the legitimacy of both legal systems, and arrangements are made to enhance the mutual interaction and joint governance of resources under a hybrid institutional arrangement such as a co-management regime (Bavinck and Gupta, Reference Bavinck and Gupta2014). These four ideal types of governance patterns are determined by the quality and intensity of relationship between the legal systems (see Table 1). The quality of relationship refers to whether the decision-making and enforcement authorities in the respective legal systems perceive the other system as valid and useful, whereas intensity indicates the degree to which the systems are interconnected (Bavinck and Gupta, Reference Bavinck and Gupta2014). The constellations of legal pluralism or governance patterns are not static and can evolve in multiple ways at various periods of governance, leading to the emergence of new institutional arrangements (von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann, Reference von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann2006). The transition to well-functioning co-management regimes in resource governance indicates the evolution of constellations of legal pluralism or governance patterns (e.g., institutional competition or accommodation) to institutional mutual support. This theoretical perspective is complemented with the ideational theory of institutional change in this study to examine the contextual scope conditions relating to the institutional environment for coastal fisheries in Ghana that could hinder the instantiation of the hypothesized causal mechanism.

Table 1. Typology of relationships between legal systems in a governance pattern

Source: Adapted from Bavinck and Gupta (Reference Bavinck and Gupta2014).

Materials and methods

Process tracing

To better understand institutions and institutional change, some institutional economists argue that economists need to go beyond quantitative evidence and statistical estimations to engage more with qualitative evidence using qualitative methods because many vital aspects of institutions and institutional change can be better explained with qualitative evidence (Schlüter, Reference Schlüter2010; Skarbek, Reference Skarbek2020). In this study, the process tracing (PT) approach, which has gained traction in qualitative social science, is adopted to examine the institutional development process for coastal fisheries co-management. PT is ‘an ideal method for understanding questions that have to do with institutional change and for understanding what factors sustain institutional outcomes’ (Skarbek, Reference Skarbek2020: 416). This is because explaining institutional change often requires a tick description evidence (Schlüter, Reference Schlüter2010; Skarbek, Reference Skarbek2020). PT is a within-case method that focuses on unpacking causal mechanisms between variables, an independent variable X (trigger) and a dependent variable Y (outcome), to generate a causal inference (Beach, Reference Beach, Wagemann, Goerres and Siewert2018). In this approach, ‘the analytical focus is on understanding processes whereby causes contribute, to produce outcomes, opening up what is going on in the causal arrow in-between’ (Beach, Reference Beach, Wagemann, Goerres and Siewert2018: 1).

PT can be divided into three variants: theory-testing, theory-building, and case-centric (explaining-outcome) PT (Beach, Reference Beach, Wagemann, Goerres and Siewert2018). While the theory-testing and theory-building variants seek to test established theories and generate generalizable theoretical explanations based on empirical evidence, respectively, explaining-outcome PT traces causal mechanisms to produce a comprehensive explanation of a historical outcome through an abductive process of juxtaposing theories and empirical material (Beach, Reference Beach, Wagemann, Goerres and Siewert2018: 17). This study adopted the explaining-outcome PT, a pragmatic approach to process tracing guided by theory. Three steps were involved in this PT: (1) conceptualization and hypothesizing the operationalization of causal mechanism from the theoretical literature on drivers of transition to co-management regimes (see Figure 1); (2) verification of the causal manifestation or existence of the conceptualized causal mechanism in the collection of evidence; (3) Operationalization through the analysis of the empirical evidence to trace the instantiation of the manifested mechanism to make causal inference. This involves searching for mechanistic evidence or traces of activities that actors leave behind in each part of the causal process. Mechanistic evidence can be in the form of patterns (predictions of statistical patterns), sequences (temporal and spatial chronology of events), traces (pieces of evidence whose mere presence provides proof), or accounts (content of empirical material such as interview narrations, minutes of meetings etc.) (Beach, Reference Beach, Wagemann, Goerres and Siewert2018: 10). The mechanistic evidence used in this study included sequences, traces, and accounts from interviews, narrations, byelaws, scholarly literature, project reports, and other grey literature.

Study area context

The study was conducted on the coast of Ghana, a regional fishing nation with a significant reliance on coastal fisheries. The fisheries sector accounts for 3.5% of the national GDP, employs approximately 2 million people, and provides 60% of the animal protein needs of Ghanaians (Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development, Reference MoFAD2020). There are over 200 coastal artisanal fishing communities in Ghana, contributing majority of annual marine fish landings (Finegold et al., Reference Finegold, Gordon, Mills, Curtis and Pulis2010). This artisanal fisheries sector is governed by customary institutions enacted by the chief fisherman (Apofohene) and national fisheries laws and regulations. In the late 1990s, co-management structures were established in 133 coastal fishing communities to ensure sustainable management of coastal fisheries (World Bank, Reference World Bank2003). The study was conducted in two of the four coastal regions of Ghana: the Central and Volta regions. These two regions were chosen because they had the strongest commitment to the co-management project (Bennett, Reference Bennett2002). The regions also differ regarding coastal fishing history and methods, socio-cultural practices, and political characteristics. The specific communities were selected based on their history of co-management and importance in the coastal artisanal fisheries sector. In the central region, three fishing communities in three different districts were selected: Cape Coast, Elmina, and Mumford. In the Volta region, the communities studied include Dzelukorpe, Abutiakorpe, Woe, Tegbi, Anloga, and Adina.

Data collection and analysis

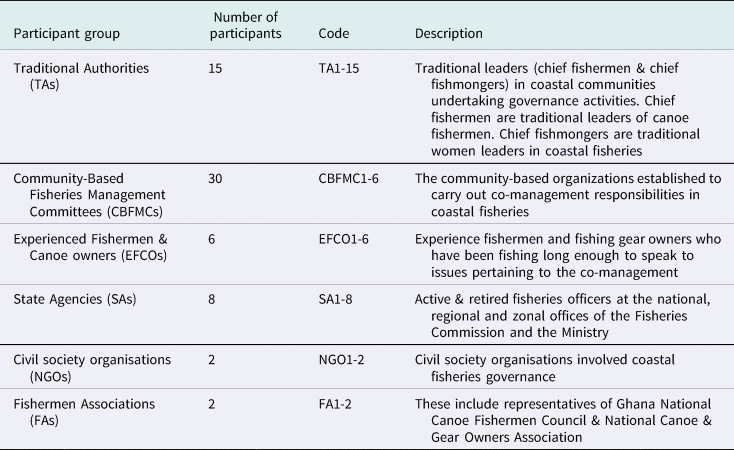

The study used qualitative research methods – semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) to collect data. In total, 63 participants were involved in the study through face-to-face interviews and FGDs during a three-month period of fieldwork (January–March 2022). The participant groups (see Table 2) included traditional leaders in fisheries governance: the chief fishermen known as Apofohene (n = 9) and chief fishmongers/women leaders known as Konkohemaa (n = 6), experienced fishermen/canoe owners (n = 6), co-management committee members (n = 30), representatives of fishers associations (n = 2), current and retired fisheries officers at zonal, regional, and national offices of the Fisheries Commission (n = 8), and representatives from civil society organizations working in the coastal fisheries sector (n = 2). The participants included both men (n = 49) and women (n = 14). The unequal representation of women in the research is due to the focus of the research and the structure of coastal fisheries governance in Ghana. While the traditional leaders of women (Konkohemaa) represent the voice of women in traditional fisheries governance, men have majority representation in the co-management committees, with only one woman in each committee. Two of the women are senior fisheries officers at the Fisheries Commission. Thus, the unequal representation of women did not affect the results obtained because each participant group had a representation of women.

Table 2. Interview participants

Source: Author.

The participant groups were purposively selected because of the peculiarity of the information sought, which could only be provided by experienced fishermen and actors who knew what transpired in the co-management processes between 1997 and 2008. A snowballing approach was adopted to identify individual participants. Of the nine communities, six FGDs comprising 30 participants were held in-person with co-management committees in six fishing communities: Dzelukorpe, Woe, Adina, Elmina, Mumford, and Cape Coast. The FGDs could not be held with co-management committees in other communities due to difficulties in organizing committee members who were not readily available during the fieldwork period. However, in-depth interviews were conducted with chief fishermen and their governing councils in all nine fishing communities. In addition, in-depth interviews were conducted with traditional women leaders in six communities. In the other communities, new Konkohemaa were yet to be installed. All interviews were conducted in the local languages (Fante and Ewe) spoken in the regions with the help of interpreters, and using English only when the respondent could understand and speak English. The topics covered in the interviews and FGDs centred on why the governance change in coastal fisheries occurred, how the development of co-management arrangements occurred, and why co-management was unsuccessful. This included probing issues of legal pluralism, potential ideological conflicts, and the historical context of coastal fisheries governance.

Most of the interviews were recorded except when participants objected during the interviews. The interviews lasted between 45 and 90 minutes. The recorded interviews were not transcribed verbatim. Detailed and observational notes were taken during and after the interviews to grasp the salient points of the conversations. The interview notes were complemented with audio recordings of the interviews, which were replayed to ensure that nothing important was missed in the data analysis. The data coding process was abductive, guided by the analytical framework, and was performed using MAXDQA software. Due to limitations regarding how accurately participants could recall events that occurred over two decades, the interview data was complemented with secondary data (grey and scholarly literature) on the historical institutional and ideological features of coastal fisheries governance in Ghana. The analysis of the evolution of fisheries governance patterns relied heavily on historical accounts in scholarly literature and grey literature. Secondary data were collected through broader searches on Google search engine, Google Scholar, and Scopus for literature on coastal fisheries governance in Ghana. The aim was not to conduct a systematic review but to generate sufficient information to triangulate and complement the empirical accounts.

Results and analysis

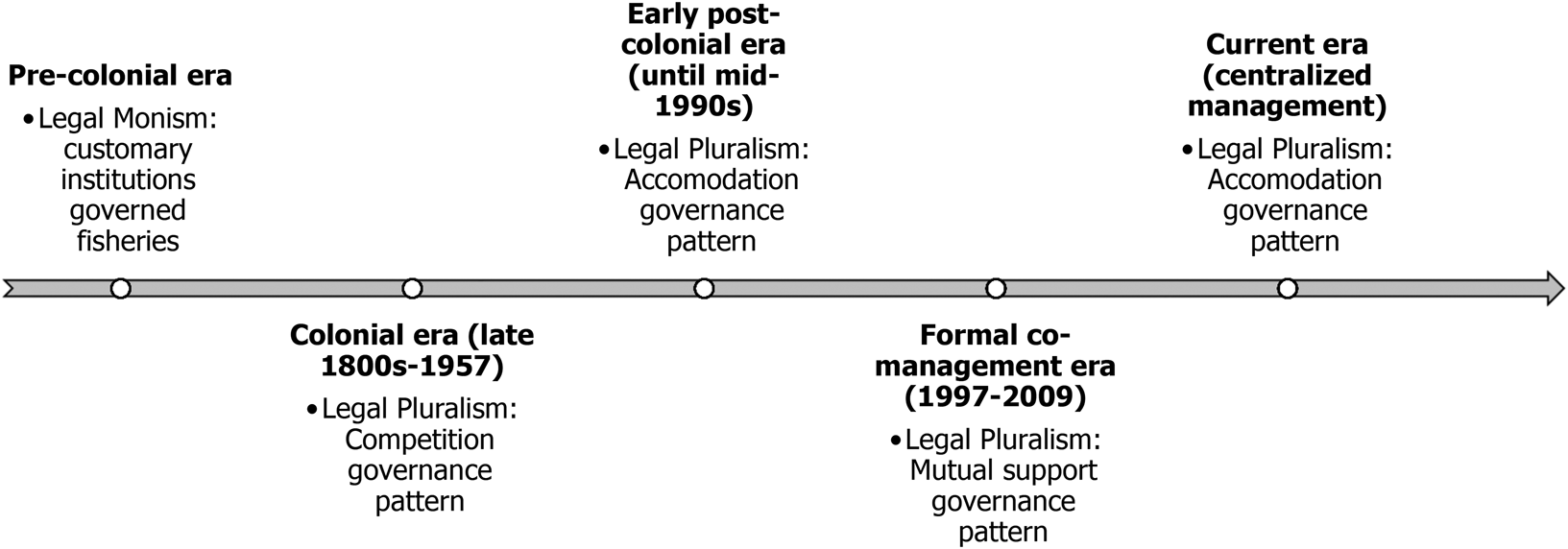

The examination of empirical data using process tracing reveals that new international/donor ideologies (ideational change) triggered the institutional development of the coastal fisheries co-management regime in Ghana. To trace the instantiation of this causal mechanism, it is essential to outline the scope conditions. Scope or contextual conditions in PT refer to the relevant socio-institutional, temporal, spatial, or analytical aspects of the setting within which the instantiation of the hypothesized causal mechanism occurs (van Meegdenburg, Reference van Meegdenburg, Mello and Ostermann2023). Here, I examine the temporal socio-institutional context of coastal fisheries governance important for spurring, changing, or limiting the instantiation of the ideational change mechanism. I begin by tracing the historical evolution of institutions for the governance of coastal resources from the precolonial (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Legal pluralism and the evolution of institutional interaction in different eras of fisheries governance in Ghana.

Source: Author.

Scope conditions: ideologies, legal pluralism, sociopolitical changes, and the evolution of coastal resource governance in Ghana

Precolonial coastal fisheries governance

Before colonialism, a thriving fishing economy existed in the Fante communities along the coast of Ghana (Walker, Reference Walker1998). The Fantes were the first to venture into marine fisheries, developed skills, technologies, and traditional rules for using these resources, and subsequently introduced marine fishing to other coastal communities (Odotei, Reference Odotei1999; Walker, Reference Walker1998). The Fante fishermen went to sea fishing with canoes, while the women developed skills in the preservation, storage, and marketing of the fish to distribute the profits throughout the year due to the seasonal nature of fishing (Walker, Reference Walker1998: 86). During this period, coastal communities governed marine coastal resources through customary institutions such as customs, norms, and taboos (Odotei, Reference Odotei1999). Traditional fisheries governance institutions comprise norms and conventions on how to access fishing grounds, fishing holidays, rules governing the type of fishing gear and fishing practices among fishermen at the beach and in the sea, norms and conventions governing the distribution of fish, and conflicts resolution mechanisms among fishermen and fishmongers (Odotei, Reference Odotei1999; Vercruijsse, Reference Vercruijsse1984).

The traditional fisheries institutions derived their sources of legitimation from the customs and culture of coastal communities and, as such, were nested in the broader traditional governance structure of the community (Odotei, Reference Odotei1999). The traditional fisheries governance in each community was led and shaped by the chief fisherman (Apofohene) and his council of elders, who together represented the authority of the Chief (traditional ruler) of the community at the beach (Interviews, TA1-9). While the chief fishermen regulated fish production, the rules for fish distribution and trade were enacted by a female leader, the chief fishmonger (Konkohemaa) (Interviews, TA10-15). Fishermen and fishmongers who broke customary rules and norms regarding fishing and fish distribution were punished through various institutional mechanisms, including providing customary items such as sheep and bottles of schnapps to appease the sea gods (Interviews, TA1-9). The ideologies of fishermen and their leaders during this period were shaped by spiritual and superstitious beliefs and subsistence objectives (Vercruijsse, Reference Vercruijsse1984; Walker, Reference Walker1998). Legal pluralism was absent during this period in coastal resource governance.

Colonialism and the emergence of legal pluralism in coastal fisheries governance

The involvement of the British colonial authorities in coastal fisheries in the 1890s led to the evolution of fisheries governance to legal pluralism, where coastal fisheries came under multiple normative orderings for the first time. Although the colonial government did not establish a Fisheries Department until 1946, colonial officers became involved in the fishing industry in the 1890s through the introduction of new technologies in the form of more efficient fishing nets, which precipitated a host of conflicts over marine space and resources (Vercruijsse, Reference Vercruijsse1984; Walker, Reference Walker1998). There were tussles between traditional and colonial authorities regarding the regulation of fishing gear in coastal fisheries. Although the colonial administration promoted the use of more productive fishing nets, traditional authorities resisted it. Arguments put forward by traditional authorities against the use of the new nets reflected ‘apprehensions about overfishing, sustainability of fisheries resources, and the maintenance of fairness, equality, and peace between fishermen’ (Walker, Reference Walker1998: 105). They argued that the use of the new nets not only led to the depletion of fishing waters, but that, such a practice was ‘a peculiarly greedy and selfish fishing method quite unusual in our fishing industry, and it is calculated to produce malicious feelings and mischievous intentions in the minds of other fishermen’ (quoted in Vercruijsse Reference Vercruijsse1984: 115). Their arguments were thus rooted in the perception that the introduction of more productive fishing gear would mark a ‘transition from an economy in symbiosis with the marine environment…to an economy exploitative of the same environment’ (Vercruijsse Reference Vercruijsse1984: 113).

However, the view of the colonial authorities was always that ‘a net which had been so successful to European fishermen must be equally useful to their Ghanaian colleagues’ (Vercruijsse, Reference Vercruijsse1984: 119). Thus, according to the Colonial Secretary of Agriculture, ‘the best fishing net is the net that catches the most fish’ (quoted in Walker Reference Walker1998: 120). In this era, ‘local governance over fisheries was undermined by legislation of the British administrators who were beginning to see Ghana's fisheries as a potentially lucrative industry for the colony’ (Walker, Reference Walker1998: 103). The colonial courts consistently ruled that the traditional authorities no longer had the right to determine appropriate fishing methods, restrict fishing, or ban fishing gear (Finegold et al., Reference Finegold, Gordon, Mills, Curtis and Pulis2010: 29). From a legal pluralism perspective, this period was marked by the conflictual governance pattern or institutional interaction known as competition. This was due to the ideological differences underlying the resource use values and norms of actors in the two legal systems (Interviews, TA1-3). It was a period of ideological conflict ‘between those in pursuit of profits, and those concerned with preserving the fisheries resource base [and a struggle] between local leaders (Chiefs and chief fishermen) and colonial leaders over who had the authority to legislate fisheries policy’ (Walker, Reference Walker1998: 116).

Evolution of institutional interaction in early post-colonial fisheries governance

Fisheries governance in the early independence era was a continuation of centralized management underlined by ‘the euphoric years of aggressive nationalism and intense struggle for economic opportunity in the wake of independence’ (Kwadjosse, Reference Kwadjosse2009: 20). Institutional development during this period reflected the ideologies of coastal fisheries as a means of maximizing short-term profits and revenues for economic growth, leading to policies favoring the industrialization of the fisheries sector (Vercruijsse, Reference Vercruijsse1984; Walker, Reference Walker1998). Inspired by the modernization ideology, the technological modernization of coastal fisheries occurred radically through technical innovation, such as the introduction of new fishing nets and outboard motors in canoe fishing (Overå, Reference Overå2011; Vercruijsse, Reference Vercruijsse1984). This occurred without any resistance from the traditional authorities, as witnessed in the colonial era (Vercruijsse, Reference Vercruijsse1984). In line with the prevailing worldwide shared-mental models about marine fisheries in that period, national regulations and ideologies underlying fisheries development in the 1960s were based on the belief that marine fisheries were inexhaustible and that Ghana had enormous fishing potential (Kwadjosse, Reference Kwadjosse2009: 19).

From the 1970s to 1992, there were structural changes in governance as Ghana came under a long period of military rule. This coincided with Ghana's ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1983, which cemented the state's de jure property rights to control access and manage coastal fisheries. While the de jure management right to the sea was vested in the state and thus regulated by the government, access rights to coastal fisheries were de facto defined by the traditional fisheries governance structures that existed historically. During this period, the government showed more interest in cooperating with traditional governance structures in coastal fisheries governance. This culminated in the formation of the Ghana National Canoe Fishermen Council (a national body of chief fishermen) in February 1982 and its formal recognition by the government (Interviews, TA4-5). From a legal pluralism perspective, the governance pattern evolved from competition to accommodation due to convergence in ideologies regarding coastal fisheries during this period. The state and fishing communities both viewed fisheries from the lens of resource extraction and profit maximization (Interview, FA1). While sustainability considerations gradually gained ground in the early 1990s because of the influence of international processes, the extractivist ideologies about coastal fisheries and their economic development rationality did not change significantly; thus, national fisheries rules and regulations thus did not limit resource extraction (Kwadjosse, Reference Kwadjosse2009).

Democratization, decentralization, and institutional evolution to co-management

Before the transition to a co-management regime, coastal fisheries had a dual governance structure. There was a traditional governance structure for fisheries comprising the chief fisherman and his council of elders (experienced and well-respected fishermen and canoe/net owners) (Interviews, TA1-9). The traditional authorities de facto controlled access to fisheries at the community level, resolved conflicts among artisanal fishermen, and set rules and customs for fishing holidays and fishermen's interactions at the beach and in the sea. Rules regarding the distribution and pricing of fish at the beach were enacted by a chief fishmonger who also works with her council of elders to resolve related issues (Interviews, TA10-15). However, the formal enactment of rules and laws for the overall governance of the fisheries sector falls under the purview of the central government, which implements fisheries regulations through the Fisheries Commission (then the Department of Fisheries). Thus, issues concerning legal fishing methods and types of fishing gear allowed for fishing were formally regulated and enforced by the state. However, there were informal collaborations between traditional authorities and the state in coastal fisheries governance (Interviews, TA1-4).

The period between the early 1980s and 1990s was characterized by transformations in the economic and governance structure of Ghana. Due to persistent economic deterioration, Ghana undertook a structural adjustment program with financing from the IMF and the World Bank, including economic liberalization, democratization, and decentralization conditionality (Devarajan et al., Reference Devarajan, Dollar and Holmgren2001). This had enormous implications for marine fisheries governance (Bennett, Reference Bennett2002). The influence of international development organizations, especially the World Bank and the IMF, on domestic institutional and economic changes was enormous. Thus, the early 1990s witnessed the decentralization of central government functions in various sectors to district assemblies, but fisheries management responsibilities were not devolved to local government bodies in the coastal districts. At the same time, resource depletion was apparent, and the sustainability discourse trickled down to the national level of fisheries governance (Kwadjosse, Reference Kwadjosse2009). However, the main approach to fisheries governance was a continuation of the centralized management regime, i.e., controlling access through licensing, establishment of fishing zones, and restrictions on fishing gear to be used within and without these zones and in the industry as a whole (Kwadjosse, Reference Kwadjosse2009: 22).

The causal process for institutional evolution to the co-management regime

Between 1997 and 2002, many institutional changes occurred in coastal fisheries governance, including the formulation of a new national fisheries law (Fisheries Act 625, 2002) and the establishmentof co-management structures known as community-based fisheries management committees (CBFMCs). This section traces the instantiation of the theorized ideational change/diffusion causal mechanism (see Figure 1) in the development of the coastal fisheries co-management regime.

Cause (X): ideational change

The transition to the coastal fisheries co-management regime was caused by a change in the cognitive and normative ideas of development and resource governance at the international level. In the 1980s, there was an evolution in academic paradigms and programmes of development and resource governance, which until the 1980s emphasized the centralization of resource management, following Garrett Hardin's ‘tragedy of the commons theory’ (Hardin, Reference Hardin1968), which became the dominant framework within which social scientists portray sustainable resource use challenges (McCay and Acheson, Reference McCay and Acheson1987: 1). The intellectual paradigm of resource governance led by new institutionalists from the 1980s espoused the value of local institutions and the sustainability potential of participatory or community-based resource management regimes (Baland and Platteau, Reference Baland and Platteau1996; McCay and Acheson, Reference McCay and Acheson1987; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990; Wade Reference Wade1987). These theoretical developments were influential in changing international ideologies and discourses of development and resource governance (Cleaver, Reference Cleaver1999; Overå, Reference Overå2011), mirroring what Higgs (Reference Higgs2008) conceptualized as theory-driven ideological change.

Thus, there was a paradigm shift in the international paradigms and programmes on development assistance, emphasizing participatory approaches for achieving the sustainability imperatives of global development. While the responsibility for environmental and resource management was entrusted to the state and emphasized in principles 7, 17, and 21 of the Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment (1972), the ideologies of resource governance changed significantly in the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992). Principles 10, 20, and 22 of the Rio Declaration strongly emphasize public and local community participation in environmental and resource management as a key pillar of sound and inclusive environmental governance for achieving sustainable development. Thus, co-management regimes emerged as a resource governance paradigm from this ‘ideological shift in development agendas that considered popular participation essential for the poor to gain access to and control over resources’ (Cinner et al., Reference Cinner, Daw, McClanahan, Muthiga, Abunge, Hamed, Mwaka, Rabearisoa, Wamukota, Fisher and Jiddawi2012: 651).

Part I: ideational brokerage

Ideas do not just emerge and become influential in decision-making and institutional building without being spread or carried by agents; they are transported from one ideational realm to another by ideational brokers (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004). These could be individual actors, epistemic communities, or international organizations that broker the flow of these ideas to actively influence ideational diffusion at the national level to drive institutional change (Campbell, Reference Campbell, Morgan, Campbell, Crouch, Pedersen and Whitley2010). The ideational change in academia and at the international level also diffused into the paradigms and programmes promoted by bilateral donor agencies and international development organizations (Cleaver, Reference Cleaver1999). The paradigm of participatory development led to changes in the World Bank's ‘institutional culture and procedures […] to adopt participation as a regular feature of its work with borrowing countries’ (World Bank, Reference World Bank1994: 1). The World Bank noted that the growing focus on promoting paradigms and programmes of participatory governance was necessary because ‘[i]nternationally, emphasis is being placed on the challenge of sustainable development and participation is increasingly recognized as a necessary part of sustainable development strategies’ (World Bank, Reference World Bank1994: 3).

The growing interest of the World Bank in institutional development in the 1990s could also be seen in key presentations by new institutional economists at the World Bank annual conference on development economics in 1994 and 1995 (See Ostrom Reference Ostrom1996; Williamson Reference Williamson1995). In the small-scale fisheries sector, particularly in developing countries, the focus of development assistance shifted from infrastructural development and technological modernization to institutional modernization and participatory resource governance in the 1990s (Cleaver, Reference Cleaver1999; Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Basurto, Smith and Virdin2021; Overå, Reference Overå2011). The World Bank thus performed the function of an ideational broker in transmitting new paradigms of participation in the development and governance of the coastal fisheries sector in Ghana (Interviews, NGO1 & SA8). The brokering of the new ideologies was achieved by capturing participatory development and governance in its 1994 country assistance strategy for Ghana (World Bank, Reference World Bank1995: 5). This was aided by the framing of participation and institutional modernization as a programme to enhance the contribution of the fisheries sector to the country's economic development (Interview, NGO1).

Part II: ideational diffusion

For ideas transported through ideational brokering to influence institutional change, they must be adopted by actors in the targeted ideational realm. Ideational diffusion can occur through several mechanisms: competition, coercion, learning, and emulation (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004). The adoption of new ideas of participation in development and governance by the government of Ghana began with the development of a 5-year institutional development project for coastal fisheries in 1995, dubbed the fisheries sub-sector capacity-building project. This project aimed to ‘modernize’ institutions (Overå, Reference Overå2011) and strengthen fisheries governance to ensure the long-term sustainability of fisheries resources and enhance their contribution to the Ghanaian economy (World Bank, Reference World Bank1995). The institutional development project was intended to be funded by the World Bank; thus, it could not diverge from the paradigms and programmes promoted in the CAS. Accordingly, the project was evaluated to be ‘fully consistent with the Bank Group's Country Assistance Strategy (CAS), [as] specifically mentioned in the CAS that was discussed by the Board on April 14 1994’ (World Bank, Reference World Bank1995: 5).

In this process, the coercion mechanism of ideational diffusion was instantiated, in which the government of Ghana adopted the new paradigms of participatory governance promoted by the World Bank to access funding opportunities. This process of ideational diffusion has also been observed in many other places, where ‘international donor agencies pressured African countries to introduce co-management or at least establish more democratic processes in the formulation of fisheries management objectives and the decentralization of fisheries governance’ (Hara and Nielsen, Reference Hara, Nielsen, Wilson, Nielsen and Degnbol2003: 82). In the case of Ghana, the diffusion of international ideologies to the national level of fisheries governance was facilitated by the influence the World Bank had on domestic policy owing to its support for the country's economic and governance transformation at the time (Interview, SA8). While resource depletion and concerns for the sustainability of the fisheries sector were important, ‘the most profound changes in fisheries governance in this period were brought about by non-fisheries concerns such as a need to respond to donor imperatives for structural adjustment and ‘good governance’’ (Finegold et al., Reference Finegold, Gordon, Mills, Curtis and Pulis2010: 3). It is well-recognized that the influence of international donors and policy advisers has had the most significant impact on how coastal fisheries are perceived and managed in Ghana (Bennett, Reference Bennett2002: 242).

Part III: institutional change

The influence of diffused ideas on institutional change can only be visible in institutionalization processes at the domestic or local level (Campbell, Reference Campbell, Morgan, Campbell, Crouch, Pedersen and Whitley2010). Institutionalization of the new paradigms of participatory resource governance occurred through the enactment of the new national fisheries law (the Fisheries Act, 2002) and the establishment of co-management structures to enhance private sector participation and sustainable governance of the fisheries sector (World Bank, Reference World Bank2003). This occurred through a top-down process whereby the government, through the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA), invited traditional authorities of fishing communities and fisheries officers to workshops to sensitize and train them on the development of the fisheries co-management regime (Interviews, NGO1 & SA7-8). This culminated in MOFA hiring a consultant to prepare a social mobilization manual for establishing the co-management regime (Interview, NGO1). The consultant prepared the manual by drawing on examples of co-management regimes in other countries and a model community-based fisheries management system in one of the fishing communities in Ghana (Interviews, TA4, NGO1, & SA8). Consultants then worked with the regional fisheries directors and fisheries officers to facilitate the establishment of co-management committees in coastal fishing communities with bylaws comprising statutory regulations and customary rules of the traditional fisheries governance of coastal fishing communities (Interviews, NGO1, SA8 & FA1).

This shows that although international ideas can be influential through coercive diffusion mechanisms, their institutionalization can often vary due to contextual conditions. Unlike other countries, where the influence of donor ideologies resulted in revolutionary institutional changes in the fisheries sector (Cinner et al., Reference Cinner, Daw, McClanahan, Muthiga, Abunge, Hamed, Mwaka, Rabearisoa, Wamukota, Fisher and Jiddawi2012), the institutional change in Ghana mainly resulted in the rearrangement of the pre-existing institutional repertoire of fisheries governance to form a co-management regime. This is a common feature of the institutionalization of international ideologies (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004, Reference Campbell, Morgan, Campbell, Crouch, Pedersen and Whitley2010). The institutional development had features of institutional bricolage (Cleaver, Reference Cleaver2012), even though bricolage in its true sense never occurred because of the lack of support from the traditional authorities in coastal fisheries.

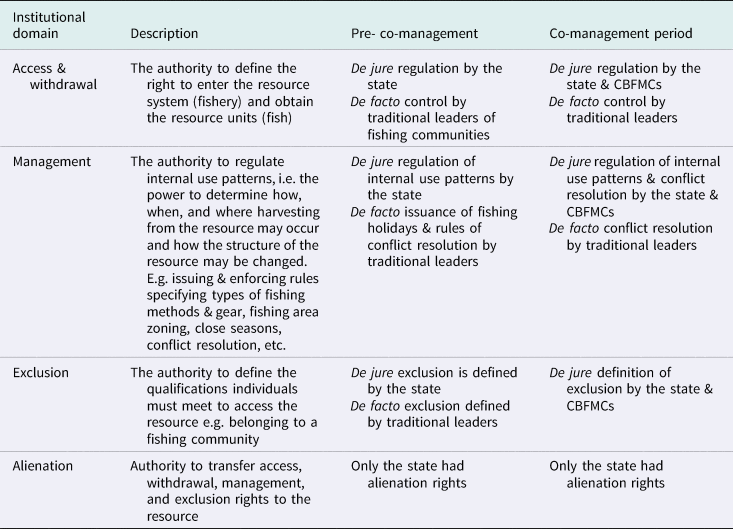

Outcome (X): coastal fisheries co-management regime

By the end of the institutional development project in 2002, 133 CBFMCs were established with their constitutions and by-laws in coastal fishing communities to ‘enforce rules and regulations designed to protect their fisheries resources’ (World Bank, Reference World Bank2003: 6). The co-management structures were created anew with a different composition of members, even though the chief fisherman or his representative should chair the committees to leverage the respect they command to implement fisheries regulations (Interviews, NGO1 & SA8). Therefore, the co-management committees operated as parallel fisheries governance structures along with the pre-existing traditional fisheries governance structures. While the co-management structures were successfully established within a short period, their effectiveness and sustainability were short-lived, as most collapsed a few years later (Finegold et al., Reference Finegold, Gordon, Mills, Curtis and Pulis2010). Drawing on the classification of property rights institutions in common-pool resources by Schlager and Ostrom (Reference Schlager and Ostrom1992), I outline changes in the distribution of institutional power owing to the transition to a co-management regime. Before the establishment of co-management structures (CBFMCs), all de jure property rights were defined by the state, but traditional authorities (chief fishermen & their councils) exercised de facto control over access and conflict resolution in artisanal fisheries at the community level (Interviews, TA1-9). The development of the co-management regime thus led to formal readjustments of the prevailing institutional arrangements and enforcement mechanisms (see Table 3).

Table 3. Distribution of power in institutional domains of the co-management regime

Source: Author, based on field interviews.

Legal pluralism, ideology, and the implementation of co-management regimes

Developing co-management regimes is a complex process in coastal fisheries in many developing countries, where legal pluralism is ubiquitous, partly because ideational conflicts may hinder institutional building and the sustainability of co-management regimes (Bavinck and Gupta, Reference Bavinck and Gupta2014; Jentoft et al., Reference Jentoft, Bavinck, Johnson and Thomson2009). While the co-management process can provide avenues for bridging the statutory and customary legal orders (Jentoft et al., Reference Jentoft, Bavinck, Johnson and Thomson2009), it requires creative processes of bricolage in which diverse ideologies are at play (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004; Cleaver, Reference Cleaver2012). Ideologies are the filters through which the appropriateness and legitimacy of newly instituted institutional arrangements in such contexts are determined, and if and to what extent actors will want to participate in collaborative governance arrangements (Cleaver, Reference Cleaver2012). The process tracing of the development of the co-management regime above indicates that the transition to coastal fisheries co-management regime in Ghana was externally driven and underpinned by donor ideologies of good governance. This was triggered by an ideological and paradigmatic shift in resource governance at the international level, which was institutionalized at the national and local levels through a top–down process. Consistent with many studies on the transition to co-management in the Global South (Cinner et al., Reference Cinner, Daw, McClanahan, Muthiga, Abunge, Hamed, Mwaka, Rabearisoa, Wamukota, Fisher and Jiddawi2012; Fabinyi and Barclay, Reference Fabinyi, Barclay, Fabinyi and Barclay2022; Ho et al., Reference Ho, Ross and Coutts2016; Orach and Schlüter, Reference Orach and Schlüter2021), the promotion of institutional modernization ideology and participatory development programs by donors influenced the adoption of the co-management regime in Ghana (Overå, Reference Overå2011). While the diffusion of the new governance paradigm was facilitated by some scope conditions, such as the socio-political changes occurring in the broader national governance structure at the time, the implementation of the institutional change was hindered by other contextual scope conditions, particularly the complexities of strong legal pluralism in coastal fisheries in Ghana.

While the tussles with the colonial authorities led to changes in the power and regulatory remit of the customary legal system in some aspects of fisheries governance, such as regulating the fishing methods and gear, the customary institutions successfully regulated access and resolved conflicts among fishermen at the community level (Bennett, Reference Bennett2002; Finegold et al., Reference Finegold, Gordon, Mills, Curtis and Pulis2010). The traditional institutional structure of coastal fisheries governance is underpinned by ideologies that underlie the broader traditional governance system of coastal communities and their ways of organizing. The worldviews of the traditional authorities are rooted in their traditional beliefs about how the broader traditional society is organized based on chieftaincy, kinship, and historical customary institutional repertoire. Most of the traditional authorities in coastal fisheries inherited their positions or are selected based on historical customary arrangements and experience in coastal fisheries (Interviews, TA1-9). They then form their own traditional councils to help perform traditional fisheries governance functions.

However, the co-management development process created new governance structures comprising a diversity of actors different from the governing councils of traditional authorities. Thus, some of the traditional authorities argue that organizing collaborative fisheries governance around a broad diversity of actors – some of whom had no affinity to or knowledge of coastal fisheries – in the name of participation through democratic representation runs counter to their norms of decision-making and how traditional governance has historically been organized (Interviews, TA1-3). Some chief fishermen of the study communities pointed out this conflict in worldviews:

We had our own ways of organizing things before the co-management committees were established. They have collapsed, and we are still here. […] If existing structures are not supported and new ones are created just like that, this will not work (Interview, TA9).

This is a typical challenge that has been recognized in the donor-driven implementation of participatory resource governance regimes, which tend to pay little attention to ideologies and power constellations in the resource context (Cleaver, Reference Cleaver2012; Ho et al., Reference Ho, Ross and Coutts2016; Russell and Dobson, Reference Russell and Dobson2011). Donor-driven participatory institutional development interventions are often project-focused and functionalist, mostly adopting an organizational approach to institutions with a strong emphasis on committees and representative participation through elections (Cleaver, Reference Cleaver1999). Thus, such organizational approaches tend to not fit with the local institutional repertoire, and existing power/societal structures may be attenuated by the introduction of new institutional structures, especially if there are strong and divergent ideological convictions (Cleaver, Reference Cleaver2012).

Also connected to the ideological convictions of the traditional authorities is the potential redistribution of incentives inherent in the customary fisheries governance structure by creating new institutional arrangements for co-management. The pre-existing customary institutional structure created certain incentives for traditional leaders who preferred the persistence of the traditional fisheries governance structure (FGDs, CBFMC1-3). The co-management arrangements were thus perceived as externally imposed government extensions to usurp the power and authority of the traditional authorities (chief fishermen) who exercise authority and control over coastal fisheries use and relations at the community level. This resulted in disinterest and lack of support for co-management structures, which was stressed as a core reason for the failure of co-management by committee members during focus group discussions:

The Apofohene here did not support the CBFMC; he was unhappy with it. He thought we were taking his power and the things he gets from the fishermen and all that. And you know he is the chief of the beach, he has power and respect of the fishermen. So, it was difficult for us to continue the committee's work, and some of us decided to stop because we did not want problems (FGD, CBFMC2).

The role of legal pluralism and conflicting ideologies in the failure of co-management was more prominent in one of the two study regions (the Central region). Issues of disagreements and conflicts between chief fishermen and co-management committee members were not mentioned during the interviews in the Volta region. This can be attributed to the level of social embeddedness of traditional fisheries governance structures, which is much stronger in the Central region. The Fantes have had a long history of traditional fisheries governance regimes modelled after the overall traditional governance structure of their society (Odotei, Reference Odotei1999). The concept of the chief fisherman in customary fisheries governance is relatively recent in the Volta region – it was modelled after the Fante traditional fisheries governance structure (Interviews, TA4-5). Thus, disagreements over and the fear of co-management arrangements unsettling the power resources and incentive structure of the traditional fisheries governance structure were minimal in the Volta region. This study confirms the observations in the broader literature that the failure to realize the hope that generated co-management is attributed to donor-driven ideologies and economic logics that run counter to the ideologies and logics of local actors and livelihood dimensions of resource users in the resource governance context (Overå, Reference Overå2011).

Contrary to findings in other contexts, where the failure of co-management regimes was attributed to a lack of prior community organizing structures and little history of community self-organization around marine resource management (Levine, Reference Levine2016), such organizational structures existed in this context. However, ideological conflicts (worldviews on what participatory governance is and how it should be organized) hindered the success of co-management. While the development of co-management was said to be intended to strengthen traditional governance structures, it was instead designed to co-opt traditional leaders (Bennett, Reference Bennett2002). The traditional governance structure, however, is not just the chief fisherman; it involves his traditional council and the ideologies and decision-making norms underpinning the customary normative order of coastal communities (Interview, FA1). Contrasting ideologies, vested interests, and disagreements between traditional authorities and co-management committees have also been found to undermine the effectiveness and sustainability of co-management regimes in inland fisheries in other parts of Africa (Etiegni et al., Reference Etiegni, Irvine and Kooy2017; Njaya et al., Reference Njaya, Donda and Béné2012; Nunan et al., Reference Nunan, Hara and Onyango2015). While inland fisheries might be distinctively different from marine fisheries in how far the transaction costs of governance can vary, it shows that establishing co-management regimes for the governance of common-pool resources is not a straightforward endeavour in contexts where legal pluralism is strong. This is not only because of the differential ideologies that underpin customary and statutory legal orders but also because of the vested interests created by pre-existing institutions in customary resource governance systems.

Constraints of the broader institutional and governance context have also been recognized as a central theme of ‘second-generation’ challenges of co-management in many other places (Ratner et al., Reference Ratner, Oh and Pomeroy2012). Local power dynamics can lead to important stakeholders, such as local politicians or traditional leaders withdrawing their support for co-management. Evidence has shown that a lack of support from such important and powerful local-level actors often presents a serious threat to the sustainability of co-management regimes (Ratner et al., Reference Ratner, Oh and Pomeroy2012; Russell and Dobson, Reference Russell and Dobson2011). The findings from this study are consistent with these observations and thus draw attention to the crucial role of local institutional and power structures in transitions to collaborative governance regimes in coastal social-ecological systems. All institutional regimes in resource governance – customary institutions/common property regimes, co-management regimes, resource nationalism (hierarchies), market-based governance, and neoliberalism (ITQs) – are representations of worldviews based on valuations of people and the environment (Fabinyi and Barclay, Reference Fabinyi, Barclay, Fabinyi and Barclay2022). Therefore, ideological convergence is necessary for co-management regimes to succeed in legal pluralistic contexts because the development of co-management in such contexts often involves navigating the institutional principles of statutory and customary legal systems, which tend to have different ideological foundations (Jentoft et al., Reference Jentoft, Bavinck, Johnson and Thomson2009).

Conclusions

This article examined the process and outcomes of governance evolution in the coastal fisheries of Ghana. The process tracing shows that the development of the co-management arrangement was driven by donor ideologies that were diffused through funding mechanisms. The ideational change that instigated the governance change clashed with the ideological foundations of the traditional governance structure, which are not based on the modernist ideals of equal representation and participatory governance. While co-management was touted as a project to strengthen traditional fisheries governance, it instead created competitive community-based fisheries organizations with attempts to co-opt the chief fishermen. The attempt to co-opt these traditional authorities did not succeed, especially in coastal communities where the social embeddedness of customary governance in coastal fisheries is stronger. The traditional authorities have a lot of power and command a great deal of respect among fishermen in coastal fisheries because they are extensions of the broader customary governance structure of Ghanaian society. Their worldviews on what co-management is, should be, and how it should be organized diverged with the modernization ideals that underpinned the co-management project.

The boundary between the exposition of worldviews and vested interests in the resistance of the traditional authorities to the design of the co-management regime is somewhat nebulous. What is clear, however, is that traditional authorities are inalienable in Ghana's coastal fisheries because of the broader institutional structure of the country. Legal pluralism is enshrined in the constitution, and a dual governance system – customary and statutory – co-exists, with chiefs as the custodians of traditional norms and rules. The chief fishermen in coastal fisheries are an extension of the remit of the traditional authorities to govern the beach, considered to be within the customary tenurial remit of traditional authorities in the coastal communities. The institutional design of the coastal fisheries co-management regime failed to align decision-making power and enforcement with the prevailing ideologies of powerful actors within the customary legal system, whose support was vital for the effectiveness and sustainability of the institutional arrangement. These findings are consistent with other studies on institutional change in small-scale fisheries, where the lack of support from powerful local stakeholders hindered the effectiveness and sustainability of co-management regimes (Ratner et al., Reference Ratner, Oh and Pomeroy2012; Russell and Dobson, Reference Russell and Dobson2011).

In conclusion, this study has shown that examining why and how institutional arrangements were created, and what ideologies shaped the emergence of such institutions, provides important avenues for understanding the practice and outcomes of collaborative common-pool resource governance regimes. The study shows how legal pluralism can complicate institutional development and practice of co-management in common-pool resource governance. Because institutional change redefines who people are and what they aspire to be (Bromley, Reference Bromley2016) and redistributes incentives in resource use and governance (Vatn, Reference Vatn2005), new institutional arrangements should fit within the prevailing cognitive and normative constraints of the institutional context to be effective and sustainable (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004). This brings attention to the role of both agency and structure, as institutional change is a process of constrained innovation. For successful governance change, the development process of co-management regimes should consider the interactions between statutory and socially embedded institutions in designing inter-legalities in a given resource governance context. Perspectives from legal pluralism and critical institutionalism provide promising analytical tools for understanding and resolving such contextual challenges of institutional development for coastal resource governance.