Reconciliation requires that all South Africans accept moral and political responsibility for nurturing a culture of human rights and democracy within which political and socio-economic conflicts are addressed both seriously and in a non-violent manner.

(Truth and Reconciliation Commission 1998:435)

South Africa's truth and reconciliation process was surely the most ambitious the world has ever seen. Not only was the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) charged with investigating human rights abuses and granting amnesty to miscreants, but the process was expected as well to contribute to a broader “reconciliation” in South Africa (the “reconciliation” half of the truth and reconciliation equation). In a country wracked by a history of racism and racial subjugation, and one just emerging from fifty years of domination by an evil apartheid regime, doing anything to enhance reconciliation between the masters and slaves of the past is a tall order indeed.

As the opening quotation illustrates, however, the truth and reconciliation process was also given the task of building a political culture in South Africa that is respectful of human rights. The process was backward-looking in the sense of being expected to document and deal with the gross human rights violations of the past, but it was also forward-looking in trying to prevent future tyranny. Its assignment was to nurture a human rights culture that would serve as a prophylactic against rights abuses in the future.

In an effort to address this mandate, the Final Report of the TRC included in its recommendations a section on the “promotion of a human rights culture” (TRC 1998:304–49). Most of the recommendations concern actions to be taken by the government (e.g., that the government recommits itself to regular and fair elections), but the TRC also urged that its report be made widely available, presumably under the assumption that those who read the report will adopt certain attitudes and values. “Culture,” as apparently understood by the TRC, largely refers to institutional actors, but may include as well the beliefs, values, and attitudes of ordinary citizens.

Many political scientists take culture very seriously and carefully distinguish between institutions and cultural values. Within our theories of democratic consolidation, establishing a culture respectful of human rights involves the creation of a set of political values and attitudes favoring human rights. A human rights culture is one in which people value human rights highly, are unwilling to sacrifice them under most circumstances, and jealously guard against intrusions into those rights. Such a culture may stand as a potent (but not omnipotent) impediment to political repression.

The charge to the truth and reconciliation process to address South Africa's culture of human rights is also a charge to social scientists to consider several important theoretical and empirical questions. Has South Africa made progress in developing a culture supportive of human rights? How widespread are such values? Are they concentrated within any particular strata within the South African population? How have these values changed? Why have they changed? Did the truth and reconciliation process itself have anything to do with how ordinary South Africans judge and value basic human rights?

These micro-level questions are all central elements of prominent theories within political science. In essence, the question is one of social learning and cultural change. Presumably (because rigorous data on the matter are not available), the old South Africa was one in which human rights abuses were tolerated if not accepted. Conceivably, this view characterized both the defenders and opponents of apartheid, in the sense that a struggle against a system as radically evil as apartheid might well have seemed to justify deviations from the strict observance of human rights. The TRC was expected to change people's attitudes and values, to teach them that human rights must be inviolable, to frame human rights as an issue essential to successful democratization. Though those who wrote the enabling legislation may not have had large-scale cultural engineering in mind when they spoke of creating a human rights culture in South Africa, social science theories certainly endorse the importance of such a culture and offer at least some clues about how it might be created.

This article has several purposes. First, it asks whether the contemporary political culture of South Africa is supportive of human rights. I attempt to answer this question through a survey of more than 3,700 South Africans, completed early in 2001. Second, I then investigate the distribution of support for human rights, beginning with the always important racial differences. Race, however, is never a very satisfactory explanation of social and political attitudes and values, so I therefore turn to more theoretically grounded explanations of variability in stances toward human rights. I assess whether there is any evidence that the truth and reconciliation process itself has had an impact on support for human rights in South Africa, especially since awareness of the TRC's activities seems to have penetrated all corners of South African society. Finally, I examine a variety of additional hypotheses—ranging from historical and contemporary experiences to interracial attitudes to preferences for different aspects of democracy—as possible explanations of the value South Africans attach to human rights. Throughout this analysis, I focus on one particular aspect of human rights—commitment to universalism (versus particularism) in the application of the rule of law. In the end, I draw the conclusion that, even though South Africa remains quite a distance from a culture in which human rights are highly regarded among all segments of the mass public, the truth and reconciliation process may well have contributed to creating a human rights culture in the country.

The Meaning of a Human Rights Culture

What those who wrote the law creating the TRC meant by the term human rights culture is not entirely clear, primarily because so many different meanings are packed into the term. The values incorporated within the concept human rights seem to include political tolerance, rights consciousness, support for due process, respect for life, support for the rule of law, and even support for democratic institutions and processes more generally. An appropriate apothegm for the meaning of a human rights culture in South Africa is perhaps everything that the apartheid regime was not.

Social scientists must of course take the concept more seriously and treat it more systematically and rigorously. One simple distinction, hinted at already, is that human rights can be enhanced by certain institutional structures (e.g., an independent judiciary) and by certain political attitudes and values held by ordinary people within the polity. Institutions and cultures are two separate entities, and the question of whether one reinforces and supports the other is a vital empirical question (see Reference IbhawohIbhawoh 2000).Footnote 1

Some who have written about human rights in South Africa emphasize the institutional underpinning of such a culture. Reference SarkinSarkin (1998), for instance, discusses the panoply of institutions connected to human rights enforcement in South Africa (e.g., the Constitutional Court, the Human Rights Commission, the Commission on the Restitution of Land Rights) in an article that refers to “culture” in its title. Sarkin's concern is whether there are institutional mechanisms that might contribute to the widening and deepening of human rights protections. The institutional infrastructure necessary to create and defend human rights in South Africa is surely crucial for this purpose, but most political scientists would treat culture and institutions as fairly distinct phenomena, each worthy of detailed investigation.

Indeed, political scientists have used the term culture to refer to the politically relevant beliefs, values, attitudes, and behaviors of ordinary citizens. Democracy—and human rights—is about more than just institutions. “The transformation of democratic forms into democratic norms…is crucial for democracy to take root” (Reference Hoffmann, Eckstein, Fleron, Hoffmann and ReisingerHoffman 1998:148). Diamond concurs, noting that the consolidation of democratic reform is only possible when

political competitors…come to regard democracy (and the laws, procedures, and institutions it specifies) as “the only game in town,” the only viable framework for governing the society and advancing their own interests. At the mass level, there must be a broad normative and behavioral consensus—one that cuts across class, ethnic, nationality, and other cleavages—on the legitimacy of the constitutional system, however poor or unsatisfying its performance may be at any point in time (1999:65).

Exactly the same may be said about the value ascribed to human rights within a culture.Footnote 2 For instance, Reference IbhawohIbhawoh (2000) cites the importance of the “cultural legitimacy of human rights” for establishing respect for human rights in practice in Africa. Thus, one way of looking at the question of whether South Africa has developed a culture respectful of human rights is to examine the attitudes and values of ordinary South Africans. How much value do ordinary people attach to human rights?

But just exactly what attitudes and values are central to human rights? One can imagine a long list of values, but surely that list would include:

• Support for the rule of law: A preference for rule-bound governmental and individual action.

• Political tolerance: The willingness of citizens to “put up with” their political enemies.

• Rights consciousness: The willingness to assert individual rights against the dominant political, social, and economic institutions in society.

• Support for due process: Commitment to nonarbitrary, explicit, and accountable procedures governing the coercive power of the state.

• Commitment to individual freedom: Undergirding all of these is a basic dedication to anything that enhances the ability of individuals to make unhindered choices.

• Commitment to democratic institutions and processes: Human rights—the rights of both majorities and minorities—are essential to making democracy function effectively.

These grand concepts provide some guidance for an empirical inquiry into attitudes toward human rights, but each of course requires a great deal more consideration and explication.

In this article, I focus primarily on support for the rule of law. I do so because a cardinal foundation of human rights is the idea that authority must be subservient to law. Law certainly does not “guarantee” human rights—rights are often lost through entirely “legal” means, and legal “guarantees” may be ultimately dependent upon political forces—but without law, citizens are dependent upon the beneficence of authorities. Unless South Africa can develop a culture respectful of the rule of law, it is difficult to imagine that human rights can prosper.Footnote 3

The rule of law is a concept subject to various definitions and interpretations. Therefore, before proceeding any further, it is worthwhile to consider in some detail the meaning of the concept from a more theoretical perspective.

The Meaning of Support for the Rule of Law

According to extant research on public attitudes toward the rule of law (e.g., Reference Gibson and CaldeiraGibson & Caldeira 1996), the essential ingredient of this construct is universalism—law ought to be universally heeded, that is, obeyed and complied with. To the extent that law generates an undesirable outcome, law ought to be changed through established procedures, rather than manipulated or ignored. Thus, willingness to abide by the law is pivotal to the concept.

The antithesis of universalism is particularism, based typically on either expedience or the substitution of some sort of moral judgment for legality. Some may feel that law should be set aside (or bent) in favor of solving problems quickly or efficiently, while others may be unwilling to accept legal outcomes that, by some standards, are “unjust.”Footnote 4 To the extent that people are willing to follow the law only if it satisfies some external criterion, the rule of law is compromised. Respect for the rule of law thus means that following the law (universalism) is accorded more weight than other values that might trump legality, such as expediency or even fairness.

“Rule of law” is a concept typically applied to the state. For instance, Skapska defines rule of law as “the legal control of anyone who wields power, …the strict observance of formal law by the authorities” (1990:700). For rule of law to prevail, there must be the

subordination of all political authorities and state officials to the law, setting limitations to their power, guaranteeing civil rights and liberties and principles of due process. The stress, next to the division of powers, [should be] put on the independence of the judiciary, on the nonpolitical character of the courts, and on the judicial control of governmental decisions (Reference SkapskaSkapska 1990:700).

But the referent for the rule of law need not be limited to the state; instead, the concept refers to both the citizen and the state. Just as the authorities ought to be constrained by legality in a law-based regime, individual citizens must respect the rule of law in their own behavior.

Violations of the rule of law do not necessarily go against the perceived self-interests of the majority. For instance, Reference Solomon, Lampert and RitterspornSolomon (1992) points to instances in the former Soviet Union in which ordinary citizens demanded that the authorities dispense with the rule of law in dealing with suspects in notorious criminal cases. There were many instances in which “people's justice” had little to do with the rule of law (and perhaps not that much to do with justice either). It is easy to imagine that runaway crime is a case in which many are willing to sacrifice the rule of law for more expedient remedies.

Many have argued that a rule-of-law state (a Rechtsstaat) is a necessary condition for democratic governance (e.g., Reference Rose, Mishler and HaerpferRose, Mishler, & Haerpfer 1998:32–3). By this they mean that the state must be bound by law and should not act arbitrarily or capriciously. As Lipset notes:

Where power is arbitrary, personal, and unpredictable, the citizenry will not know how to behave; it will fear that any action could produce an unforeseen risk. Essentially, the rule of law means: (1) that people and institutions will be treated equally by the institutions administering the law—the courts, the police, and the civil service; and (2), that people and institutions can predict with reasonable certainty the consequences of their actions, at least as far as the state is concerned (1994:14).

Authoritarian regimes are notorious for their antipathy to the rule of law. Solomon asserts: “Soviet officials and politicians were not used to subordinating their interests to law. Many of them treated the law as an instrument to be embraced when useful and ignored when expedient. In short, their actions reflected the syndrome known as ‘legal nihilism'” (1992:260).The “telephone justice” of socialist legal practice in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union emphatically represents the antithesis of the rule of law (see Reference MarkovitsMarkovits 1995).

I must acknowledge, however, that freedom is often lost under the mantle of law; and not all authoritarian governments necessarily reject the rule of law. As Krygier reminds us, “There was, after all, a Nazi jurisprudence, and it was a horrible sight” (1990:641). Much of the early Nazi attack on German Jews was accomplished under the authority of law. And of course, few governments today would repudiate the rule of law openly, since the rule of law is a powerful and seemingly universal means of legitimizing authority. But legality can serve tyrants just as well as democrats.

Thus, I contend that the rule of law is a continuum bounded by universalism and particularism. Though the concept usually is applied to the state, it is equally apposite to the behavior of individual citizens. Further, though rule of law is most likely necessary for democratic government, it certainly is not sufficient. The rule of law may be enlisted by both dictatorial minorities and tyrannical majorities. Finally, rule of law has meaning as an attribute of institutions, of cultures, and of the belief systems of ordinary citizens. This last point describes the empirical focus of this research.

The Rule of Law Under Apartheid

Some debate exists about whether the apartheid regime in South Africa was based on the rule of law. Certainly, many of the repressive actions taken against the “Black”Footnote 5 majority were grounded in laws properly adopted by the parliament—after all, apartheid itself was a comprehensive legal edifice. Indeed, in its Final Report, the TRC found that “Part of the reason for the longevity of apartheid was the superficial adherence to ‘rule of law’ by the National Party (NP), whose leaders craved the aura of legitimacy that ‘the law’ bestowed on their harsh injustice” (TRC 1998:101).

But the government also seemed to follow law only when it was expedient to do so; no elemental and principled commitment to a law-based state characterized apartheid. Revelations from the hearings of the TRC make absolutely plain that the rule of law was frequently suspended by the apartheid authorities as they became increasingly threatened by the liberation forces during the 1980s.Footnote 6 The suspension of law was manifest in the various declarations of states of emergency (accomplished through legal procedures), but more significant was the widespread lawless repression apparently authorized and paid for by the state (e.g., the Civil Co-operation Bureau [CCB]—see, for examples, Reference PauwPauw 1997; Reference De Kockde Kock 1998). Thus, the historical legacy of apartheid is not one that contributes much to the rule of law.

Nor were all elements of the liberation forces particularly devoted to the rule of law. The African National Congress (ANC), though undoubtedly essential to the liberation of South Africa, committed gross human rights violations of its own, including atrocities in its training camps (about which it established its own “truth commission” to investigate these atrocities—see Reference Hayner, Villa-Vicencio and VerwoerdHayner 2000). Perhaps more important, barbarous and lawless acts were committed in the name of the ANC as the organization lost control of many of its operatives in the late 1980s and early 1990s.Footnote 7 For example, it is difficult to treat the “necklacing” of individuals—a method of killing somebody by putting a gasoline-filled tire around the person's neck and then setting it alight—as having anything to do with the rule of law.Footnote 8 Though the liberation forces were not as cavalier as the apartheid state when it came to setting law aside, the rule of law was clearly a casualty of the liberation struggle.

Indisputably, the TRC documented that gross human rights violations were committed by both agents of the apartheid state and the liberation forces. For instance, Desmond Tutu asserts in the Final Report, “We believe we have provided enough of the truth about our past for there to be a consensus about it. There is consensus that atrocious things were done on all sides” (TRC 1998:18). Moreover, the culpability of the ANC, the UDF, and Winnie Mandela is vividly discussed in the report (1998: 240–9).Footnote 9 The authors of the report are even more emphatic: “If the TRC ignored or failed to acknowledge the extent to which an individual, the state, or a liberation movement, either legally or illegally, deployed its resources systematically to violate the rights of others, it would have failed to give a full account of the past” (Reference Villa-Vicencio, Verwoerd, Rotberg and ThompsonVilla-Vicencio & Verwoerd 2000:286).Footnote 10 I am not asserting that any sort of parity existed in the crimes committed in the name of or in opposition to apartheid, but it would be quite natural to come away from the truth and reconciliation process with the view that all sides in the struggle held fairly weak commitments to the rule of law.

Thus, little in South Africa's past suggests that the rule of law would be a deeply cherished value. The TRC consequently was presented with a difficult task of building a human rights culture in South Africa respectful of the rule of law.

Research Design

This analysis is based on a survey of the South African mass public conducted in 2000–2001.Footnote 11 The fieldwork began in November 2000, and “mop-up” interviews were completed by February 2001. The sample is representative of the entire South African population (ages 18 and older). A total of 3,727 interviews were completed. The average interview lasted 84 minutes (with a median of 80 minutes). The overall response rate for the survey was approximately 87%. The main reason for failing to complete the interview was inability to contact the respondent; refusal to be interviewed accounted for approximately 27% of the failed interviews. Such a high rate of response can be attributed to the general willingness of the South African population to be interviewed, the large number of callbacks we employed, and the use of an incentive for participating in the interview.Footnote 12 Most of the interviewers were women, and interviewers of every race were employed in the project. Most respondents were interviewed by an interviewer of their own race. The percentage of same-race interviews for each of the racial groups was African, 99.8%; white, 98.7%; Coloured, 71.5%; and South Africans of Asian origin, 73.9%.

Interviews were conducted in the respondent's language of choice, with a plurality of the interviews conducted in English (44.5%). The questionnaire was first prepared in English and then translated into Afrikaans, Zulu, Xhosa, North Sotho, South Sotho, Tswana, and Tsonga.Footnote 13 The methodology of creating a multilingual questionnaire followed closely that recommended by Reference BrislinBrislin (1970). Producing an instrument in this many languages that is conceptually and operationally equivalent is a very difficult task, and we have no doubt that a considerable amount of measurement error was introduced by the multilingual context in which this research was conducted. Nonetheless, we took all possible steps to minimize this error.

Because the various racial and linguistic groups were not selected proportional to their size in the South African population (so as to ensure sufficient numbers of cases for analysis), it was necessary to weight the data according to the inverse of the probability of selection for each respondent. In addition, we applied post-stratification weights to the final data in order to make the sample slightly more representative of the South African population.

Race in South Africa

I have already made reference to the major racial groups in South Africa: blacks, whites, Coloured people, and South Africans of Asian origin. Though these categories were used by the apartheid regime to divide and control the population, these are nonetheless labels that South Africans use to refer to themselves (see, for example, Reference Gibson and GouwsGibson & Gouws 2000, Reference Gibson and Gouws2003). Nothing about my use of these terms should imply approval of anything about apartheid or acceptance of any underlying theory of race or ethnicity.Footnote 14

The Nature of South African Support for the Rule of Law

I asked the South African respondents to express their agreement or disagreement with four statements measuring support for the rule of law (with the response supportive of the rule of law following in parentheses):

1 Sometimes it might be better to ignore the law and solve problems immediately rather than wait for a legal solution. (Disagree)

2 It's alright to get around the law as long as you don't actually break it. (Disagree)

3 In times of emergency, the government ought to be able to suspend law in order to solve pressing social problems. (Disagree)

4 It is not necessary to obey the laws of a government that I did not vote for. (Disagree)

Each of these statements juxtaposes a value against strictly following the law. For example, the first item asks the respondent to make a choice between expediency and adherence to the rule of law. Table 1 reports the responses to these four measures of support for the rule of law.

Table 1. Support for the Rule of Law

Note: The percentages are calculated on the basis of collapsing the five-point Likert response set (e.g., “agree strongly” and “agree” responses are combined) and total across the three rows to 100% (except for rounding errors). The means and standard deviations are derived from the uncollapsed distributions. Higher mean scores indicate greater support for the rule of law. The results of statistical tests evaluating the interracial differences in responses to these statements are reported in the following footnotes.

a p<0.000; η=0.16;

b p<0.000; η=0.30;

c p<0.000; η=0.16;

d p<0.000; η=0.25;

e p<0.000; η=0.33;

f p<0.000; η=0.34.

These measures do not, of course, represent all possible facets of the rule of law. Earlier research has shown, however, that many components of the concept evoke consensus from ordinary people (Reference Gibson and CaldeiraGibson & Caldeira 1996). For instance, it is a waste of survey items to ask whether the government ought to be allowed to govern arbitrarily, setting law aside whenever necessary or expedient, or whether courts ought to be subservient to politicians. Contrariwise, the results in Table 1 reveal that people do indeed differ in the strength of their commitments to law and legality.

Furthermore, this distinction between “legal universalism” and particularism has been recognized in many earlier studies of attitudes toward the rule of law as a central feature of the concept (e.g., Reference Gibson and GouwsGibson & Gouws 1997; Reference Gibson, Galligan and KurkchiyanGibson 2003). In the analysis that follows, I use the term rule of law, but in every instance I mean legal universalism—whether “law ought to prevail unless there are severe exigencies to the contrary” or whether “law is something to be manipulated or ignored in pursuit of one's own self interests (variously defined)” (Reference Gibson and CaldeiraGibson & Caldeira 1996:60).

The first thing to note about this table is that generally, support for the rule of law is not particularly widespread in South Africa. A majority of South Africans believe it is okay to get around the law so long as the law is not broken (Item Two); that in an emergency law should be suspended in order to solve social problems (Item Three); and that a plurality would ignore the law if necessary to solve problems immediately (Item One). Only on the issue of whether one should obey a law passed by a government that one did not vote for (Item Four) does a majority in support of the rule of law emerge. In general, the respondents are quite divided in their judgments of the importance of the rule of law, with South Africans strongly committed to legal universalism constituting a minority in their country.

The table also documents that significant racial differences exist in the responses to each proposition. Based on the mean replies, African South Africans are in every instance least likely to support the rule of law. Conversely, whites are the most likely to endorse the rule of law. The differences are in some instances quite substantial, as in the statement that it is okay to get around the law if you do not actually break it: 60.6% of the white respondents disagree with this statement, while only 27.4 % of the black Africans are similarly inclined. On most items, Coloured people and those of Asian origin hold attitudes similar to Africans. In terms of the number of these rule-of-law propositions endorsed, whites expressed support for 2.4 statements, those of Asian origin supported 1.8 statements, Coloured people 1.7 statements, and Africans on average voiced support for the rule of law regarding only 1.4 of these items. These are fairly large and substantively significant racial differences (see the eta statistics (η) summarizing the extent of interracial differences in the responses to these questions). It is particularly troubling that support for the rule of law is so limited among the African majority.

Cross-National Comparisons

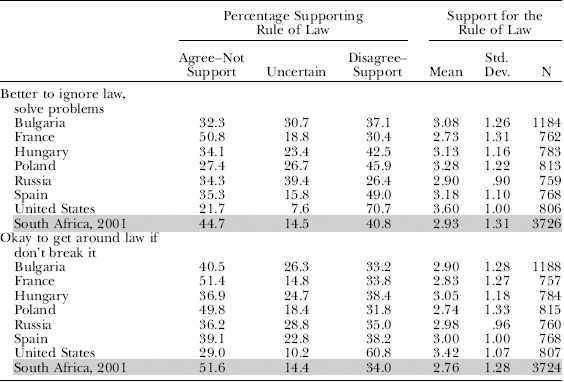

It appears that South Africa is some distance from a culture based on widespread support for the rule of law. But in order to gain better perspective on these South African results, it is useful to compare them to surveys conducted in other countries. Fortunately, some of these same statements have been put to representative samples in a number of European countries and in the United States.

In 1995, the Survey of Legal Values was conducted in seven countries.Footnote 15 That survey included several propositions measuring support for the rule of law, based on the same conceptualization as used in the South African study (i.e., some alternative value is juxtaposed against strictly following the law). Two of the items were identical to statements used in the 2001 South African survey. In Table 2, I report the responses to both of the items for each country.

Table 2. Cross-National Comparisons of Attitudes Toward the Rule of Law, 1995

Note: The percentages are calculated on the basis of collapsing the five-point Likert response set (e.g., “agree strongly” and “agree” responses are combined) and total across the three rows to 100% (except for rounding errors). The means and standard deviations are derived from the uncollapsed distributions. Higher mean scores indicate greater support for the rule of law.

The items read:

Sometimes it might be better to ignore the law and solve problems immediately rather than wait for a legal solution. (Disagree)

It's all right to get around the law as long as you don't actually break it. (Disagree)

The starkest conclusion from these data is that Americans exhibit an unusual degree of attachment to the rule of law. For instance, consider the first item in Table 2: “Sometimes it might be better to ignore the law and solve problems immediately rather than wait for a legal solution.” An overwhelming majority of Americans disagree with this statement, thereby expressing their commitment to the rule of law, in contrast to only 40.8% of the South Africans. Nearly twice as many Americans as South Africans believe it improper to bend the law. South Africa and the United States stand out in sharp contrast in the data in this table.

The South Africans, however, are not especially distinctive in their rejection of the rule of law. Indeed, on both of these statements, the South Africans reject the rule of law at approximately the same level as the French (although francophone cultures generally seem not to hold law in particularly high regard). There can be no doubt that South African political culture is characterized by less support for the rule of law than American culture but, when compared with Europeans, the South Africans do not stand out as unusual in their commitments (or lack thereof) to law.

From these data, it appears that a culture deeply respectful of the rule of law has not yet been established in South Africa, even if it may not have been established in all mature democracies as well. Perhaps most important, large racial differences exist in attitudes toward law. The remainder of this article will consider whether race is a surrogate for other, more theoretical, variables and processes.

Support for the Rule of Law and the Truth and Reconciliation Process

To what degree are contemporary attitudes toward the rule of law related to the activities of the truth and reconciliation process? This question is of course quite difficult to answer definitively without longitudinal data on how attitudes have changed. The ideal research design has been lost to history, since such a design would involve interviewing the same people before and after exposure to the activities of the process.Footnote 16 In the absence of such data, I pursue two approaches to answering this question. First, I consider whether support for the rule of law in the aggregate has increased, based on a comparison between these 2001 data and an earlier comparable survey we conducted in South Africa in 1996 (Reference Gibson and GouwsGibson & Gouws 2003). Second, I investigate whether the cross-sectional evidence is compatible with the conclusion that the truth and reconciliation process shaped attitudes toward the rule of law.

Change in South African Attitudes Toward the Rule of Law

Because these same statements were put to a representative sample of South Africans in 1996 (Reference Gibson and GouwsGibson & Gouws 2003), I can compare the responses in 2001 to those five years earlier. One might hypothesize that two factors have contributed to an increase in respect for the rule of law. First, the lawmaking institutions of the New South Africa have far more legitimacy than those of the apartheid era, at least among Africans and probably among Coloured people and those of Asian origin as well.Footnote 17 Laws in South Africa today are made within an institution (Parliament) that is politically accountable to the (black) majority. Second, greater experience with democratic governance and procedure may have enhanced respect for the rule of law. In many respects, law serves the interests of the majority today, rather than repressing that majority and denying it rights and liberties. Thus, a reasonable expectation is that support for the rule of law would be more widespread in 2001 than in 1996.

On the other hand, I should note that whatever the objectives of the truth and reconciliation process, many aspects of the process may well have contributed to undermining respect for the universal application of the rule of law. An obvious example is amnesty—extending freedom from prosecution to those admitting horrific violations of South African laws is likely not a formula for enhancing respect for law. Moreover, the defense that amnesty was necessary to avoid civil war in essence asserts that expediency, albeit an extremely significant expediency, should trump law. Even the departures from legalistic procedures in the hearings of the TRC, as well as the condemnation by the Constitutional Court of at least some of the most egregious deviations from due process, cannot have taught South Africans the value of strict adherence to the law. Thus, there are many good reasons for suspecting that the truth and reconciliation process in South Africa actually had exactly the opposite effect than was intended by those who created it. The data in Table 3 allow this hypothesis to be tested.

Table 3. Change in Support for the Rule of Law

Note: The percentages are calculated on the basis of collapsing the five-point Likert response set (e.g., “agree strongly” and “agree” responses are combined) and total across the three rows to 100% (except for rounding errors). The means and standard deviations are derived from the uncollapsed distributions. Higher mean scores indicate greater support for the rule of law.

Nothing in Table 3 supports the conclusion that the rule of law has become more firmly established in contemporary South Africa. In nearly every instance, the mean scores in 1996 and 2001 are quite similar. Indeed, from a statistical point of view, the proper conclusion is that there has been little change in attitudes toward the rule of law between 1996 and 2001.

These data seem to suggest that the truth and reconciliation process may have had limited influence on attitudes toward the rule of law among ordinary people in South Africa. The data are not dispositive, however, in that aggregate-level change (such as that reported in Table 3) can (and often does) mask substantial micro-level change. If those becoming more sympathetic toward the rule of law are counterbalanced by those becoming less sympathetic, the overall appearance may be one of stasis when in fact considerable change is taking place. For the moment, however, these data yield little evidence indicating that the truth and reconciliation process contributed to more widespread support for the rule of law in South Africa.

The Influence of the TRC

In order for the truth and reconciliation process to influence attitudes toward the rule of law, people must have been attentive to the Commission and acquired some awareness of its activities. A necessary condition for influence may be awareness.Footnote 18 In addition, it is reasonable to hypothesize that those with greater confidence in the TRC are more likely to endorse the rule of law. Finally, those who accept the findings of the TRC—the “truth” or collective memory produced by the TRC (see Appendix A for measurement details)—are also expected to be more steadfast supporters of legal universalism.

In order to test these hypotheses, I regressed rule of law attitudes on three indicators of the respondents' understanding of the TRC: awareness of its activities, confidence in the Commission, and acceptance of the TRC's truth about the country's apartheid past. I also included two control variables—the extent of media consumption and interest in politics in general—so as to try to more carefully pinpoint the influence of the truth and reconciliation process itself, as compared to more general media use and political awareness. I expected that support for the rule of law would be more common among those who are aware of the TRC, who trust it, who accept its truth, who are more attentive to the media in general, and who are interested in politics. Table 4 reports the results of this regression.

Table 4. Support for the Rule of Law and the Truth and Reconciliation Process

Note: The coefficients are:

b=unstandardized regression coefficient

s.e.=standard error of the unstandardized regression coefficient

β=standardized regression coefficient

r=bivariate Pearson correlation coefficient

* p≤0.05;

** p≤0.01;

*** p≤0.001.

The most important conclusion from this table is that, in general, those who accept the truth as produced by the TRC are more likely to support the rule of law. The statistical relationships are quite substantial for Africans (β=0.25), whites (β=0.28), and Coloured people (β=0.23). Among those of Asian origin, the coefficient is positive (β=0.07) but not statistically significant, so it is not clear that truth acceptance and the rule of law actually go together. But for the vast majority of South Africans, endorsing more of the TRC's truth is related to a stronger acceptance of the need for universalism in law.

This finding requires further explication. In particular, what specifically is the connection between accepting the TRC's truth and valuing the rule of law? The two variables are no doubt linked by the Commission's insistence on applying rules and principles of human rights equally to all combatants in the struggle over apartheid. It is the TRC's insistence on universalism—judging all sides in the struggle according to the same criteria—and its unwillingness to accept arguments to the effect that ends justify means—that a “just war” can excuse violations of the rule of law—that cement the truth-legal universalism relationship. I admit that causality is always difficult to establish (especially with cross-sectional data), but the TRC's lesson is that law (human rights) must be respected by all, and those accepting that lesson are more committed today to universalism in the application of the rule of law in South Africa.

Still, it is debatable whether the activities of the TRC have actually caused these attitudes, since the coefficients for knowledge and confidence in the TRC are weak or trivial for all of the groups. One would not expect perhaps that the multivariate effects of knowledge and confidence would be very strong—since their influence on support for the rule of law should be mediated through endorsement of the TRC's truth—but the bivariate relationships (representing the total effects of the variables—r) are generally weak as well. In no instance is greater awareness of the activities of the TRC significantly related to attitudes toward the rule of law.Footnote 19

Understanding the coefficients linking confidence in the TRC to rule-of-law attitudes presents some challenges. For whites, greater confidence is related to more support for the rule of law, as predicted. For Coloured people, no significant relationship exists. But for the African majority, the relationship is negative: Those expressing more confidence in the TRC are less likely to support the rule of law. Though the coefficient is, strictly speaking, indistinguishable from zero, the same may be true for those of Asian origin as well. The inverse relationship presents a conundrum for the hypothesis.

Perhaps for some Africans the TRC itself actually represents a violation of the rule of law.Footnote 20 After all, the TRC's main job is to override the traditional criminal law that would punish people for their criminal deeds. The TRC may therefore be understood as abrogating law instead of enforcing it. One who believes that law ought to be universally applied, irrespective of the consequences, would surely find it difficult to support letting some of South Africa's most notorious criminals go free after admitting their heinous crimes. Perhaps the meaning of this coefficient among Africans is that those predisposed toward the universal application of law have found it difficult to have confidence in the TRC, even though they paid attention to the activities of the Commission and accepted some of its conclusions about South Africa's apartheid past.

It is noteworthy, however, that whites seem not to be influenced by the same processes, since commitment to the rule of law is positively (and significantly) related to confidence (β=0.10). This is all the more surprising once the stronger commitment of whites to the rule of law is recalled. Perhaps whites who express confidence in the TRC do so in part because they view the Commission as legally constituted and, in the end, at least somewhat rule-bound in its proceedings (even if occasionally forced to adopt such rules by litigation and court judgments). Still, many whites condemned the TRC for engaging in a “witch hunt” (whatever the truth of the matter), so one might have expected that this coefficient would be negative, with the rule-of-law supporters expressing less confidence in the TRC. Though the relationship is weak, the data indicate otherwise.

Political interest and media consumption do not affect attitudes toward the rule of law among Africans or those of Asian origin. Among whites and Coloured people, greater interest in politics is associated with greater support for the rule of law. It is difficult to understand all of these individual coefficients. The important thing to note, however, is that the effects of the variables concerning the TRC are not dependent upon a person's level of interest in politics and the magnitude of her or his media consumption.

Thus, I have unearthed some evidence that the truth and reconciliation process may have shaped attitudes toward the rule of law in South Africa. Those who accept the truth about South Africa's past as promulgated by the TRC are more likely to endorse the rule of law. For three of the four groups (and thus for the vast majority of South Africans), these relationships are reasonably strong. The causal processes involved remain a bit murky, as they almost always are with cross-sectional analysis. But at a minimum, I confidently conclude that truth acceptance and respect for law go together in South Africa. And even if the truth and reconciliation process has not caused enhanced support for human rights, little evidence indicates that the process has significantly undermined respect for the rule of law.

Other Processes Contributing to Support for the Rule of Law

Factors other than the activities of the truth and reconciliation process may well have shaped South Africans' attitudes toward the rule of law. In particular, I consider several hypotheses.

Experience

Here I include historical experiences with apartheid, and contemporary perceptions of the seriousness of the crime problem in South Africa. Since some South Africans fared better under apartheid than others, I hypothesize that those victimized more are more likely to hold the rule of law in low regard.Footnote 21 In addition, the perceived escalation of crime since the demise of apartheid, especially among whites, may have eroded support for legal universalism.

Racial Reconciliation

Attitudes toward the rule of law may reflect perceptions of who will benefit from law—the white minority or the “Black” majority. Among some Africans, “rights” have long been synonymous with “white rights.” As Klug observes, “…even John Dugard, a long-standing supporter of a bill of rights for South Africa, expressed concern that those who have suffered long outside the protection of the law are now unwilling to see their oppressors brought within the protection of the law…” (2000:76). Consequently, I hypothesize that racial animosity influences attitudes toward legal universalism, with those feeling more positively about South Africans of other races being more likely to support the rule of law.

Strong Majoritarianism

The rule of law is sometimes portrayed as a means of constraining the will of the majority. In a sense, the rule of law is the antithesis of power; it is meant to require the majority not to act on the mere basis of the power of its majority status but instead to act legally. In a liberal democratic polity, the legal process typically extends some power to political minorities through promises of minority rights. Thus, I hypothesize that those who believe strongly in the rights of the majority are less likely to support the rule of law.

Individualism

Similar reasoning applies to beliefs about the importance of the individual. The rule of law is often seen as a means of protecting individuals (perhaps only temporarily) from the wrath of the group. For instance, Ibhawoh sees a “fundamental conflict between the implicit individualism of human rights and the importance of collectivism and definitive gender roles in most African cultures” (2000:853). Thus, I expect that those who value individuals more highly in general are more likely to support universalism in the application of the rule of law.

Ideology and Political Preferences

The governing majority in South Africa is of course the ANC. The rule of law has often been bound up in ideological debates about race and rights in South Africa, especially during the constitution construction process in the mid-1990s. Rights and law are viewed by some as a means of constraining the power of the ANC to bring about social change, especially changes that might be contrary to the interests of whites.Footnote 22 I therefore consider the hypothesis that attitudes toward law are a function of ideological commitments and preferences, as in the hypothesis that supporters of the ANC are less enthusiastic about the rule of law because the constraints of law are most likely to be applied against the governing majority. If people judge the rule of law in terms of whether their side profits from it or not, then attitudes toward the ANC should predict preferences for legal universalism. Because the IFP has traditionally held such a strong position in Kwa-Zulu Natal, I also include a measure of affect for the IFP as a predictor of support for the rule of law.Footnote 23

Control Variables

South Africa is characterized by sharp cleavages along many different lines. I therefore include a variety of control variables for class, gender, urban-rural differences, and literacy and education. I also incorporate the controls for media consumption and interest in politics considered above. Finally, I use a measure of opinion leadership to test the elitist hypothesis that local influentials are more committed to the rule of law than ordinary people.

Appendix B addresses the measurement of the various predictors. Table 5 reports the results of the separate regressions for each of the four racial groups.

Table 5. Multivariate Determinants of Support for the Rule of Law

Note: The coefficients are:

b=unstandardized regression coefficient

s.e.=standard error of the unstandardized regression coefficient

β=standardized regression coefficient

r=bivariate Pearson correlation coefficient

* p≤0.05;

** p≤0.01;

*** p≤0.001.

A remarkable degree of similarity characterizes the findings across the four groups. In each instance, those more strongly committed to majoritarianism are less likely to support the rule of law. These relationships are reasonably robust. For South Africans of every race, law seems to be perceived as a mechanism for preventing the majority from getting what it wants. Those who believe in strong majoritarianism are much less likely to believe in legal universalism. Attitudes toward South Africans of other races also influence attitudes toward law for all four groups, although the strength of the relationship varies somewhat across the groups. Generally, those holding more conciliatory racial attitudes are more likely to support the rule of law.

The effect of these two variables—racial reconciliation and majoritarianism—may indicate that commitments to the rule of law are to some degree instrumental rather than principled. I have no direct way of measuring whether the respondent believes he or she directly profits from the strict enforcement of the law, but it seems that attitudes toward law are bound up with beliefs about the conflict between the majority and the minority in South Africa. Those reconciled with the opposite race are perhaps less threatened and therefore feel less need for the protection of law, just as those supporting strong majority rule seem not to want strong constraints from legality. The rule of law seems to be associated with the interests of the minority (however that minority is defined), presumably because the majority can protect itself with power, without the need for recourse to law.

The finding that acceptance of the TRC's truth influences legal attitudes is unshaken by the multivariate analysis. Except for South Africans of Asian origin, those accepting more of the TRC's truth about the country's apartheid past are more likely to support law. Perhaps these people learned from the TRC's revelations the terrible consequences of lawlessness and therefore place their hopes on the constraints associated with the rule of law.

Just a handful of the other variables has any influence at all on attitudes toward the rule of law. South Africans of Asian origin who are more strongly committed to individualism support law more, although individualism has little impact on most South Africans. Similarly, Asian women are less likely to support the rule of law, but only slightly, and generally this view does not characterize most South African females. Perhaps the most interesting idiosyncratic finding is that Asian South Africans more favorable toward the IFP are less likely to support the rule of law, even though their attitudes toward the ANC are unrelated to legal preferences. Perhaps this relationship is better put in the negative—Asian South Africans holding more antipathy toward the IFP are more likely to support the rule of law. This no doubt has something to do with the history of intense political conflict (indeed, at some recent points, warfare) involving the IFP in Kwa-Zulu Natal (the home of most of the Asian respondents).

It is worth noting that many factors have no influence whatsoever on attitudes toward the rule of law. Particularly interesting is the finding that having been harmed by apartheid has no effect on legal attitudes. When put together with the evidence that accepting the TRC's truth does shape attitudes, this seems to suggest that attitudes have been shaped more by learning about the past than experiencing it. This is in part surely a function of the fact that, for many, apartheid is becoming a distant memory, but it also gives greater credence to the claim that the TRC's revelations had some independent influence on attitudes toward law.

Also surprising is the finding that perceptions of crime have little if any influence on attitudes toward the rule of law. Few would have predicted this result. Perhaps this reflects an ambivalence about law and crime. Some of those fearful of crime surely want strict enforcement of the law, but others may prefer getting around legal constraints in order to crack down on crime. Given this mixture of views, the coefficients linking crime concern and support for legal universalism would be trivial, as they are. It seems from these data that fear of crime in South Africa is not inimical to the rule of law.

A host of demographic variables has little or no influence on legal attitudes. Urban-rural differences, social class, age, opinion leadership, and education and literacy generally have very small effects at best. Particularly noteworthy is the lack of influence of social class, as is the weak relationship between level of education and legal attitudes. At least a portion of these findings has to do with the fact that these background variables are related to the attitudes that predict support for the rule of law, and that once those attitudes are controlled, socioeconomic differences have no residual influence.

One “background” factor poorly understood in this analysis is race, since the data in Table 5 analyze differences within, not across, races. One further analytical step is therefore necessary to combine the effects of these substantive variables and race.

To address more comprehensively the influence of race, I regressed rule-of-law attitudes on three sets of variables: (1) substantive variables—truth acceptance, racial reconciliation, and support for strong majoritarianism;Footnote 24 (2) three racial dummy variables—distinguishing Africans from whites, Coloured people, and South Africans of Asian origin; and (3) interaction terms—the interactions among the three substantive and three dummy variables. I then performed hierarchical regressions, adding the interactive terms separately for each set of substantive attitudes, and then adding all interactive terms to the equation simultaneously. The hypotheses considered under this analysis were (1) that the intercepts differ across races (the groups differ in levels of support for the rule of law), and (2) that the slopes for each of the substantive independent variables differ across race (the factors shaping attitudes toward legal universalism vary by race).

The regression analysis is absolutely unambiguous with regard to attitudes toward majoritarianism and racial reconciliation—the slopes across the four racial groups differ insignificantly. The influence of these two substantive variables is not dependent upon the respondent's race.

The influence of truth acceptance (as represented in the regression coefficients for the various interactive terms) does seem to vary across race, but not greatly. Among South Africans of Asian origin, whether one accepts the truth about the past has less influence on attitudes toward the rule of law (b=−0.22, p=0.002), with acceptance of the truth having little influence within this group (b=(0.25–0.22)=0.03). The effect of truth on attitudes toward law is slightly diminished among whites (b=−0.08, p=0.052), although the resulting coefficient is not reduced to insignificance (b=(0.25–0.08)=0.17).

The effect of race on the intercepts, however, is quite different. Even within the full equation (i.e., the equation with all interaction terms), the dummy variable for whites is highly significant (p<0.000), with whites, ceteris paribus, substantially more committed than Africans to the rule of law (a=(2.83+0.73)=3.56). Black and Coloured South Africans do not differ in their attitudes (p=0.235), but there is a substantial difference between Africans and those of Asian origin (p=0.007, a=(2.83+0.93)=3.76). Thus, even when one takes into account feelings about majoritarianism, truth acceptance, and racial reconciliation, whites and South Africans of Asian origin are more strongly committed to the rule of law than are Africans.

Discussion and Concluding Comments

Several important conclusions emerge from this analysis. First, South Africans are not inordinately supportive of the rule of law, even if their lack of support is not unusual from the point of view of some established European democracies. Second, strong racial differences exist in commitments to law, with Africans and Coloured people exhibiting much weaker support for legal universalism. Third, I have adduced some evidence that the TRC has had an influence on attitudes toward the rule of law through its exposure of the abuses of law under the apartheid regime and through its demonstrated commitment to the universal application of principles of human rights. Finally, attitudes toward the rule of law have much to do with beliefs about the relationship between majorities and minorities in South Africa. Supporters of the rule of law seem to endorse weaker forms of majoritarianism and stronger forms of minoritarianism and to hold more tolerant attitudes toward South Africans of different races.

This last point deserves considerable emphasis. Rather than reflecting concrete experiences, either contemporaneous experiences with crime or historical experiences with apartheid, attitudes toward the rule of law instead reflect more basic democratic values. Those who have not learned the complex lessons of democracy have also failed to learn about the importance of the rule of law. This seems to imply that, for some, law is politicized in South Africa. Rather than being a means of protecting all South Africans from arbitrary and abusive action, law may be seen as means of protecting the privileged minority. I suspect that some South Africans view law as a means by which whites maintain their hegemony in South Africa. If so, this is an important, and ominous, finding.

It may well be that since South Africans have had little experience with legal universalism, they have yet to learn of its value. The TRC seems to have had some influence on attitudes toward law, although I admit that the evidence of causality is not as strong as it might be. By exposing people to the consequences of arbitrary government not constrained by law and by judging all sides in the struggle according to the same criteria, the truth and reconciliation process may have deepened and widened respect for law.

One of the “negative” findings of this analysis also warrants emphasis: Support for the rule of law is not related to perceptions of crime and criminality in South Africa. Many have feared that the demand to “do something” about crime would result in the under-mining of law in the country. In fact, that seems not to be the case, at least from the point of view of ordinary South Africans.

Nor are attitudes toward the rule of law related to experiences under apartheid. This is an important finding because it indicates that, at least on this issue, the legacy of apartheid may be fading.

This analysis has not addressed all important issues related to the rule of law. For instance, these data say little about tolerance of corruption or willingness to make courts subservient to politics or the substance of the law that legal universalism would enforce. Nor have I investigated other byproducts of the truth and reconciliation process, such as the legitimacy the process seems to have extended to expectations of amnesty for wrongdoings of every sort (e.g., fixing cricket matches) and to the relaxation of due process constraints on hearings of various sorts. These are all important omissions, and one must be careful about overgeneralizing from these findings to broader conclusions about the future of the rule of law and the consolidation of democracy in South Africa.

Nonetheless, a central problem of all new democracies, South Africa included, is minoritarianism. South Africans are deeply intolerant of political differences (Reference Gibson and GouwsGibson & Gouws 2003); many have not accepted the virtues of the liberal half of the liberal democracy equation (majority rule + minority rights). Still, it is perhaps surprising that the rule of law is associated with minoritarianism—one might have guessed that the universalism of law would be attractive to everyone. Instead, it seems that intolerance, strong majoritarianism, and disregard for the rule of law go together in the minds of many South Africans. This is not a formula for successful consolidation of democracy and the protection of human rights.

South African democracy is still in its infancy. A decade ago, the country was wracked by political violence more widespread and severe than ever experienced during the heyday of apartheid. South African political culture was deeply scarred by apartheid, with vestiges of antidemocratic attitudes and practices that will take generations to overcome. Whites have surrendered but a small portion of their privileges, and they continue to dominate economically and socially, if not politically. Thus, from this perspective, it is perhaps extraordinary that so many South Africans hold law in any regard at all and that they are willing to set their immediate interests aside and accept legal processes and outcomes. Broadening and deepening the respect with which law is held by ordinary South Africans should be among the highest priorities for those committed to a more democratic future for the country.

Appendix A

The TRC's View of the Truth About South Africa's Past

One of the variables used in this analysis indicates the degree to which each respondent accepts the findings of the TRC about South Africa's apartheid past. I do not necessarily assume that there is an objective history of the past; instead, I assume that there is a view that has been constructed through the efforts of the truth and reconciliation process. The TRC clearly adopted as one of its missions the creation of a history of apartheid in South Africa, and the Commission sought to encourage all South Africans to accept its version of that history. Therefore, the “truth” I investigate is the truth as proposed and endorsed by the TRC.

What did the TRC proclaim about South Africa's apartheid past? Whether one agrees with the findings or not, the central elements of the TRC's understanding of the country's history include the following:

• Apartheid was a crime against humanity, and therefore those struggling to maintain that regime were engaged in an evil undertaking.

• Both sides in the struggle over apartheid committed horrific offenses, including gross human rights violations.

• Apartheid was criminal both due to the actions of specific individuals (including legal and illegal actions) and because of actions of the state institutions themselves.

In order to provide an empirical indicator of truth acceptance, we asked the respondents to judge the veracity of five statements about South Africa's apartheid past. These statements (and the position deemed to represent the conclusions of the TRC) are:

1 Apartheid was a crime against humanity. (True)

2 The struggle to preserve apartheid was just. (False)

3 There were certainly some abuses under the old apartheid system, but the ideas behind apartheid were basically good ones. (False)

4 The abuses under apartheid were largely committed by a few evil individuals, not by the state institutions themselves. (False)

5 Both those struggling for and those struggling against the old apartheid system did unforgivable things to people. (True)

These five statements are simple, widely accepted (at least throughout the world, if not in South Africa), are interrelated, and the veracityFootnote 25 of the statements would surely not be controversial among the leaders of the truth and reconciliation process themselves.Footnote 26 As I demonstrate elsewhere, there is a close connection between these propositions and the conclusions of the TRC as chronicled in its Final Report.

For purposes of hypothesis testing, it is useful to devise a summary index indicating the degree to which each South African accepts the truth as defined here. On the basis of the responses to these five statements, I calculated an index of truth acceptance. To produce a measure with more variance by taking advantage of the intensity of beliefs, I also employed the average response to these items (after scoring each item such that a high score indicated greater agreement with the TRC's truth). I used this measure in the analytical portion of this research.

Cross-race differences in truth acceptance are statistically significant, but are far from large, with η=0.15. Not surprisingly, blacks are most likely to accept the veracity of these statements, whereas whites are least likely. However, the substantive differences are not nearly as great as one might have anticipated—the median number of items accepted for Africans, whites, Coloured people, and those of Asian origin is 3.

Appendix B: Measurement of Independent Variables

Experience

I developed a measure of the degree to which each respondent believes he or she was harmed by apartheid based on the following question. The index is simply the average number of harms experienced.

Here is a list of things that happened to people under apartheid. Please tell me which, if any, of these experiences you have had.

Note: The response set for these items is:

1 Yes

2 No

• Required to move my residence

• Lost my job because of apartheid

• Was assaulted by the police

• Was imprisoned by the authorities

• Was psychologically harmed

• Was denied access to education of my choice

• Was unable to associate with people of different race and colour

• Had to use a pass to move about

Two indicators of perceptions of crime were included:

There has been some talk recently about crime in South Africa. In terms of how it affects you personally, would you say that in the last year the level of crime has got worse, has not changed, or has got better?

1 Got better

2 Has not changed

3 Got worse

[IF WORSE] Would you say that crime has got a great deal worse, moderately worse, or only a little worse in comparison to last year?

1 Got a great deal worse

2 Got moderately worse

3 Only a little worse

Please tell me how important each of the following problems is to you personally—very important, important, not very important, or not important at all.

Racial Reconciliation

The respondents were asked nine questions about members of the “opposite race.” That is, Africans were asked the following questions with regard to whites; all other respondents were asked the questions using Africans as the reference group. The index employed is the balance of reconciled to unreconciled responses.

• I find it difficult to understand the customs and ways of [the opposite racial group].

• It is hard to imagine ever being friends with a [the opposite racial group].

• More than most groups, [the opposite racial group] are likely to engage in crime.

• [the opposite racial group] are untrustworthy.

• [the opposite racial group] are selfish and only look after the interests of their group.

• I feel uncomfortable when I am around a group of [the opposite racial group].

• I often don't believe what [the opposite racial group] say to me.

• South Africa would be a better place if there were no [the opposite racial group] in the country.

• I could never imagine being part of a political party made up mainly of [the opposite racial group].

Strong Majoritarianism

The index is the average response to the following items:

• The party that gets the support of the majority ought not to have to share political power with the political minority. (Agree)

• The constitution is just like any other law; if the majority wants to change it, it should be changed. (Agree)

• If the majority of the people want something, the constitution should not be used to keep them from getting what they want. (Agree)

• Voting in South African elections should be restricted to those who own property. (Disagree)

Individualism

The index is the average response to the following items:

• People should go along with whatever is best for the group, even when they disagree. (Disagree)

• It is more important to do the kind of work society needs than to do the kind of work I like. (Disagree)

• People have to look after themselves; the community shouldn't be responsible for the actions of each citizen. (Agree)

• The most important thing to teach children is obedience to their parents. (Disagree)

Ideology and Political Preferences

I measured affect toward the ANC and IFP with the following questions:

And now I'd like to ask you about your attitudes toward some groups of people. I am going to read you a list of some groups that are currently active in social and political life.

Here is a card showing a scale from 1 to 11. The number “1” indicates that you dislike the group very much; the number “11” indicates that you like the group very much. The number “6” means that you neither like nor dislike the group. The numbers 2 to 5 reflect varying amounts of dislike, and the numbers 7 to 10 reflect varying amounts of like toward the group.

The first group I'd like to ask you about is Afrikaners. If you have an opinion about Afrikaners please indicate which figure most closely describes your attitude toward them. If you have no opinion, please be sure to tell me. What is your opinion of…?

Supporters of the ANC

Supporters of the Inkatha Freedom Party.