Statues and memorials that celebrate national heroes or events appear to be an eye-catching phenomenon in the nineteenth-century urban environment. Cities all over Europe adorned their squares and boulevards with public monuments to promote a cosmopolitan atmosphere. Moreover, the presence of these sculptures in public space has led historians to assume that the creation of a monumental landscape was an important tool in the construction of collective identities, first and foremost a modern national identity. The statues and memorials ought to ‘remind’ passers-by of their collective past and present heroes, and in doing so supposedly facilitated the invention of a shared (national) story in the present.Footnote 1 Yet while the intended message of the monuments is often clear, the popular perception of the statues and memorials has been little problematized. This contribution explores how the monumental landscape of nineteenth-century Amsterdam generated multilayered meanings and usages in daily urban life and demonstrates how the urban perspective is therefore crucial to understanding popular nation building.

In his seminal study Nations and Nationalism since 1780, Eric J. Hobsbawm already framed modern nation-states as ‘dual phenomena’ that were ‘constructed essentially from above, but which cannot be understood unless also analysed from below, that is in terms of the assumptions, hopes, needs, longings and interests of ordinary people, which are not necessarily national and still less nationalist.’Footnote 2 Especially in an urban context, ordinary citizens were confronted again and again with nationalist agendas and ‘invented traditions’ of the upper classes.Footnote 3 Nineteenth-century urban planning gave room to political actors to arrange and control public space. The city served as a décor in which national identities and symbols could take on concrete shapes. The focus of urban historians has been predominantly on the intentions of these city planners.Footnote 4 Whether the great mass of ordinary people, by whom I mean citizens without formal political or institutional power, subscribed to these elitist nation-building agendas is open to question.

This contribution explores the popular interaction with the monumental landscape of late nineteenth-century Amsterdam.Footnote 5 Above all, this article shows the perception and practical uses of statues and memorials in daily urban life and reconstructs what happened after the unveiling ceremonies, when the brand-new monuments were left on their own. From the 1850s, Amsterdam tried to catch up with international metropolitan trends and transformed into a modern city.Footnote 6 It is evident that its public monuments made a strong intervention in the nineteenth-century urban environment. Yet I will make clear that their capacity to express a (national) message did change over time and – in some cases – might even become lost. I will argue that most city dwellers showed little interest in the original message and demonstrate how they established new interpretations of, and alternative uses for, the statues and memorials in their daily lives. The popular experience of urban space will therefore be central to the analysis, as the study of the meaning of public statues and monuments calls for a more socially oriented approach.

Inspired by the influential work of Henri Lefebvre on ‘everyday life’, numerous studies have been published on the impact of the physical environment on the lives of city dwellers. These studies primarily focus on people's daily experiences in the city. For example, in the edited volume The City and the Senses (2007), Alexander Cowan and Jill Steward present a variety of research on the importance of sight, sound, smell, touch and even taste in urban culture from the early modern period until World War II.Footnote 7 They argue that the sensory dimension of city life not only shaped everyday behaviour but also determined the relation between people and spaces. Nicholas Kenny, in his study of the urban experience of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Brussels and Montreal, states how the modernization process that took off in the nineteenth century generated new stimuli for the city dweller. This resulted in a range of competing identities: ‘The significance with which space is imbued is often the product of conflicts and compromises between competing spatial stories, making the city a theatre for the affirmation of identity and status’.Footnote 8

In recent years and under the influence of the spatial turn, political historians as well have become more receptive to the importance of space in (political) identity formation.Footnote 9 In Streetlife (2011), Leif Jerram pleads in favour of the city as the best place to study modern political history. In particular, he pays attention to the non-elite practices in urban space; according to his view it is in the city's streets and in the lives of ordinary people that the big events in history took concrete shapes.Footnote 10 At the same time, Jerram shows how difficult it is to link the concrete physical space to the political experiences of city dwellers.Footnote 11 Concerning the formation of national identities in the urban context, scholars keep coming back to the topic of representation and the analysis of the symbolical meaning of the physical environment.Footnote 12 How city dwellers themselves thought of the political symbolism and how these interventions in urban space impacted on social practices remains diffuse.

It does not come as a surprise then that the historiography of public monuments is characterized by a top-down approach as well. The ideologies and agendas of the initiators, who often came from the middle or higher social classes, are central to the historical analysis.Footnote 13 This has led to impressive comparative studies, for example the work of Helke Rausch on public monuments in nineteenth-century Paris, Berlin and London.Footnote 14 Rausch shows how in these three European capital cities middle-class nationalists and the authorities deliberately used statues and memorials as (sometimes contested) tools in the process of nation building. As a consequence, both political and urban historians have given a lot of attention to the iconography of public sculptures. The variety of topics and styles offered new ways to access the ideological world of the initiators and the intended message of the monuments.Footnote 15 In this respect, the monumental landscape is closely linked to the study of public architecture, like parliamentary buildings or prestigious national museums.Footnote 16

The study of the popular perception of public statues and memorials is highly underdeveloped, as Rausch remarks in a footnote. She claims that the ‘crucial question’ of the perception of public monuments in Europe remains unanswered. In particular, the way different groups in society – social, political, religious, gender or age – related to the monumental landscape and how their views were either congruent with or at odds with official rhetoric remain unclear.Footnote 17 Moreover, the spatial situation of public monuments, and the implications of the location for the experience of the statues and memorials, was often overlooked by political historians. Research on popular interaction with the monuments has been limited to either their role in festive and commemorative cultures or the occasions when the sculptures were perceived as controversial.Footnote 18 The study of exceptional events has been given preference over the study of day-to-day experiences, which might be caused by the availability of source material.

This contribution focuses on the statues and memorials as part of daily city life. The statue of the (now famous) seventeenth-century painter Rembrandt van Rijn, the first monument to be unveiled in Amsterdam in 1852, serves as a starting point for analysis. In the first section, I focus on what message the initiators wanted to convey. In their speeches during the unveiling ceremony, the initiators clearly addressed a national community, but they were not very concerned with transmitting the ideas behind the statue to a larger audience. In the second part of this article, I demonstrate how the location and placement of the monument influenced popular perception. The divergence between the design and use of public space will be discussed here as well. In the third and final section, I analyse how the city dwellers interacted with the statues and memorials in daily life and demonstrate how we could tackle the source problem of writing history from below.Footnote 19 Since passers-by leave few traces, we have to find other methods of reconstructing popular ideas about the monumental landscape. This contribution therefore not only puts forward the question whether ordinary people responded to the intended meaning of the statues and memorials, but also aims to show how far the historical sources can bring us in studying popular interaction with nineteenth-century monuments.Footnote 20 A close reading of known and often used sources, like brochures or newspaper reports, enables us to extract new information about these urban groups that did not belong to the upper social classes or local government. In particular, the use of visual sources like drawings, engravings and photographs will allow me to capture both the prescribed and actual daily interaction of ordinary citizens with the monumental landscape, a topic I will return to in the final part.

The message and its audience

While a true statuomanie or Denkmalswut dominated big nation-states like France and Germany, the number of statues and memorials established in the Netherlands during the nineteenth century is slightly disappointing.Footnote 21 Throughout the country, about 40 of these public monuments were erected.Footnote 22 By ‘public’, I mean that the statues and memorials were accessible or at least viewable from street level. The city of Amsterdam counted three statues, two busts and one national memorial; in comparison to other nineteenth-century Dutch cities, this was already a relatively high number.Footnote 23 The small number of monuments did not imply that (national) identity formation was of little importance for the Netherlands and its capital. During the second half of the nineteenth century, Amsterdam would manifest itself as the centre of Dutch cosmopolitan culture.Footnote 24 The city became the stage for national festivities and commemorations, which attracted attention from all over the country.Footnote 25 In this respect, Amsterdam did not differ from other nineteenth-century European capitals.

In the following paragraphs, I will focus on the initiators of the Rembrandt statue and the nationalist message they communicated to the broader (urban) audience. Like elsewhere in Europe, the initiative to erect a monument was usually taken by a private party, sometimes financially assisted by the municipal council or members of the monarchy. In the case of the Rembrandt statue, a small group of prominent painters from Amsterdam and The Hague had launched the plan. They were inspired by the statue of the seventeenth-century painter Rubens that was erected in Antwerp (Belgium) in 1840.Footnote 26 The money that would be needed for the production of the statue was collected through fund-raising. The fund-raising campaigns emphasized the importance of collective action: according to the initiators, it was only with the (financial) assistance of ‘every Dutchman’ that the plan would have a chance to succeed. In reality, it was mainly the elite who contributed to the statue of the seventeenth-century painter. From the 402 subscribers in total, the majority lived in Amsterdam (58 per cent) and The Hague (29 per cent).Footnote 27

The best way to access the central message behind the public monuments is to have a look at the unveiling ceremonies. The unveiling of the Rembrandt statue, which took place on 27 May 1852, was staged as a nationalist performance. Every speech emphasized the national character of Rembrandt and especially the public importance of the statue. The mayor of Amsterdam expressed his hope that many citizens and strangers would be able to admire the painter:

It will be a permanent sign of how in the nineteenth century the people of the Netherlands, in honour of themselves, recognized the merits of their ancestors. But above all the statue will be a stimulus for the contemporary citizens and their offspring to support – in the painter's footsteps – the national arts and uphold the national honour and thus pay tribute to the immortal Rembrandt van Rijn in the most dignified way.Footnote 28

Internationally, Rembrandt was already recognized as a symbol of the Dutch ‘Golden Age’. In the Netherlands, the painter had not yet reached such a status, although this only encouraged the initiators to present Rembrandt as a national icon and figurehead for the arts in general.Footnote 29 The statue was to remind present and future generations of the achievements of their ‘immortal’ ancestor.Footnote 30

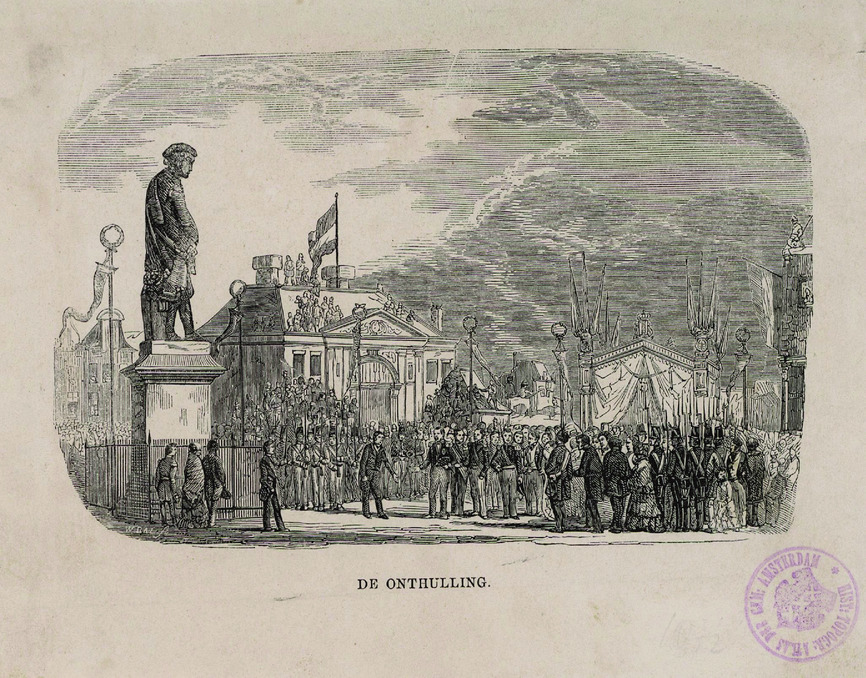

Historiography has shown how at the unveiling ceremonies the statues and memorials became part of a Festkultur.Footnote 31 Should we read this as an indication of popular interest in the nationalist message? In 1852, the inhabitants of Amsterdam expressed a strong curiosity for the festivities in honour of the first statue in their city. Weeks in advance, the owners of the houses that surrounded the venue advertised in the local newspapers rooms with a view of the events.Footnote 32 Pictures show how during the ceremony people even climbed the roofs to gain a better view, a practice confirmed by journalists (Figure 1).Footnote 33 In his speech, the mayor self-assuredly stated how ‘thousands and thousands’ of citizens from all social backgrounds had participated in the event.Footnote 34 The input of the audience, however, was limited. We can safely presume that from a rooftop or at the back of the crowd it was difficult to become part of the ceremony. Afterwards, people complained that they had not heard or seen anything during the entire event. ‘Because of all the shouting and cheering the crowd could not hear a syllable of what had been said’, concluded Joris Praatvaar (‘George Babbler’), the fictional protagonist of a popular brochure on the Rembrandt festivities.Footnote 35

Figure 1: During the unveiling ceremony of the statue of Rembrandt, people climbed the roofs to gain a better view. Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Collectie Tekeningen en Prenten, 10097/010097007715, ‘Onthulling van het standbeeld van Rembrandt’, 1852.

The spatial organization of the ceremony had even further consequences. Rausch has already mentioned in her study of the pompous unveiling ceremonies in France, Germany and Great Britain how the areas where the festivities took place were often fenced off.Footnote 36 In 1852, a news reporter who was present at the unveiling of the Rembrandt statue noticed how the audience was divided in two distinct groups: ‘For the invitees a separate space was created, ranging from the royal gallery past the statue.’Footnote 37 One could enter the terrain only with a costly admission ticket. The above-cited Joris Praatvaar was not interested in the rumour that tickets were being resold outside the venue: ‘I didn't think it worth the money’, he told his (fictional) neighbour.Footnote 38 In depictions of the event, we can see how the king, the speakers and the important guests who were dressed in colourful uniforms, with sashes and medals, stood close to the statue, while the other spectators had places further away.Footnote 39 The important nineteenth-century social demarcation between the ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ classes was accentuated by the spatial organization of the ceremony, thus generating a very specific definition of the ‘national community’.

When we take a look at other unveiling ceremonies in nineteenth-century Amsterdam, we discern a similar pattern. In 1856, the nationalist monument in commemoration of the Ten Days’ Campaign against the southern Netherlands (present-day Belgium) in 1830–31 was erected on Dam Square. Pictures of the ceremony show how gentlemen in top hats took the best places near the pedestal. They were separated from the other spectators by rows of uniformed military and a large wooden fence.Footnote 40 As an exception to the rule, this time free festivities were organized after the ceremony, which were attended by many city dwellers. In 1876, at the unveiling ceremony of the statue of the nineteenth-century liberal statesman Johan Rudolf Thorbecke, a barrier separated the official guests and the spectators as well.Footnote 41 In the case of the unveiling of the statue of the seventeenth-century poet Joost van den Vondel (1867) and the bust of the local physician and philanthropist Samuel Sarphati (1886), the general public was excluded from the entire event: these statues were placed in public parks that were – for the occasion – accessible only with an admission ticket.Footnote 42

Despite the rhetoric about the public use and nationalist significance of the monuments, ordinary citizens often had no proper access to the festivities. In 1852, the Amsterdam-based newspaper Algemeen Handelsblad wrote how the unveiling of Rembrandt had been a true ‘celebration of the nation’ (vaderlandsch feest), to which not only the attendance of the king, but also the presence of important representatives of the arts, the nationalist decorations at the venue and most of all ‘the noble joy displayed by the crowds’ had contributed.Footnote 43 Yet in essence, the event was a performance not for the ‘thousands and thousands’, as the mayor had suggested, but only for a limited social circle. In 1876, on the occasion of the unveiling of Thorbecke's monument, contemporaries even used the term ‘homely’ (huiselijk) to emphasize the importance of how all guests belonged to the same social network.Footnote 44 The inhabitants of Amsterdam enjoyed the buzz that came with the unveiling, and as such became involved with the ceremony, yet it remains highly uncertain whether the intended message reached these ordinary city dwellers.

Claiming public space

In the second part of this article, I will focus on how the inhabitants of Amsterdam responded to the ‘monumentalization’ of their city. A contemporary thematic map of the nineteenth-century capital shows how the various monuments were clearly presented as landmarks: they were pointed out to the map-reader (presumably a tourist) with a small drawing.Footnote 45 The construction of a monumental landscape was a prestige project. As a rule, statues and memorials were erected on squares and boulevards or in public parks. These central locations increased the public visibility, and urban historians have shown how the initiators intentionally used this aspect of the urban landscape.Footnote 46 This points to a transformation in what was perceived as a suitable place for commemoration and which spaces in the city were experienced as ‘public’. In the early modern period, churches or city halls were regarded as appropriate places to commemorate important persons or events through elaborate memorials. These buildings could be freely accessed by the general public.Footnote 47 In the nineteenth century, the practice of commemoration moved to the city streets. ‘In the Netherlands, the age of tombs is replaced by the age of statues’, an Amsterdam publisher concluded in 1867.Footnote 48 The city functioned as the place where collective heroes were presented and produced. In everyday life, however, the design of the public monuments frequently did not correspond with the perception of the ordinary city dweller. In this section, I will demonstrate how especially the lower-class inhabitants of Amsterdam experienced the monuments as an invasion of ‘their’ public space.

Popular brochures published shortly after the unveiling of the Rembrandt statue offer a first impression of the perception of the monument in daily city life. After considering various locations, the initiators decided on a popular marketplace in the city centre, named the Botermarkt (‘Butter Market’).Footnote 49 This square was an important junction in – the still very modest – urban traffic, positioned between the commercial city centre, the Jewish working-class neighbourhood and the expensive upper-class residential area of the Herengracht. As a marketplace, it attracted visitors from all walks of life. In a poem published in 1856, the Rembrandt statue ‘expressed’ his enthusiasm about the bustle surrounding his pedestal.Footnote 50 Other brochures published directly after the unveiling ceremony cited more critical comments. In a ‘dialogue’ between Rembrandt and the Botermarkt, for example, the lowbrow and everyday atmosphere of the marketplace was presented as a disgrace to the painter (‘the smell of urine is turning my [that is, Rembrandt's] stomach’).Footnote 51

These publications help us to deduce some first perceptions of the monuments, although it is important to keep in mind that the (often anonymous) authors did represent the popular experience in an indirect way. What becomes clear is that the daily users of the Botermarkt had (or were supposed to have) little to no clue about the background of the statue. Moreover, city dwellers thought the tribute to the seventeenth-century painter interfered with their urban space. Examples of these feelings are shown by the poem ‘Lamentation by Rembrandt van Rhijn’, which was written in 1852 by the local schoolmaster Jan Schenkman (1806–63). Although the city dwellers in Schenkman's poetry were fictional, the author was praised in reviews of his work for his ability to convey popular opinion.Footnote 52 It therefore seems not too far-fetched to believe his poetic expressions mirrored actual popular feelings about the statue and its surroundings.

Schenkman introduced his readers to two working-class women, called ‘Mie’ and ‘Lijs’, who apparently were unimpressed by Rembrandt's artistic merits:

Other city dwellers who made their appearance in the poem were critical of the costs and the uselessness of the statue or characterized the initiative as idolatry. Some users of the Botermarkt did complain about the loss of precious commercial space. Schenkman ‘cites’ a local trader who clearly claims the Botermarkt as his square:

The popular brochures display the new and different usage of the urban space after the unveiling of the Rembrandt statue. The monuments were placed in already existing environments; no ‘new’ space was created for these private initiatives. This resulted in conflicts with the ‘original’ users.

The claim of the Rembrandt statue on the popular Botermarkt only expanded when the municipal authorities aimed to transform the square into a decent bourgeois space. With these interventions, the authorities tried to influence popular behaviour. In 1876, the statue of the liberal statesman Thorbecke was erected a few hundred metres away from that of Rembrandt. This led to a large-scale renovation of the Botermarkt and the adjoining Kaasmarkt/Reguliersplein (‘Cheese Market’). Both squares were meant to attract more ‘civilized’ user groups, and passers-by should be stimulated to look at the statues of Rembrandt and Thorbecke with respect. One of the effects was that the location that had been used for decades as a marketplace was taken away from the inhabitants of Amsterdam with the arrival of both statues. Already in the 1860s and 1870s, market activities were banned from the area, and a small park was created to surround the Rembrandt statue in 1876. The municipal council thus supported the original intention of the initiators and at the same time tried to give this part of the city a more respectable and cosmopolitan appearance.Footnote 54

The rearrangement of the squares and the call for a more ‘decent’ use of the space was also reflected in street names.Footnote 55 In 1876, the Botermarkt was rechristened as Rembrandtplein (Rembrandt Square): a symbolic act, yet one that strengthened the impression that the dominance of the statue over the public space was irreversible. Simultaneously, the Reguliersplein was named after Thorbecke. A similar process was visible in the case of the other sculptures: the public park that housed the Vondel statue was rechristened as Vondelpark (previously: ‘Nieuwe Park’). The Sarphatipark was named after the bust of the famous local in 1886; and anyone who nowadays leaves the Central Station immediately enters the Prins Hendrikkade, named after the bust of Hendrik, prince of Orange (1885), that was located opposite the station until 1979.

These interventions in public space seemed to cause some protests. G.H. Kuiper, member of the Thorbecke committee, reported to the police about local youths who were throwing cobble-stones at the pedestal of the bronze statesman, presumably because of annoyance with the slow progress of the renovation.Footnote 56 The statue also played a role in the 1876 riots regarding a ban on the annual fair, which took place a few months after the unveiling. Again, it was the statue's claim on public space, not its political background, that seemed to trigger this popular response.Footnote 57 Other examples show the central message of the initiators did come through with the city dwellers. The Amsterdam schoolmaster and writer Theo Thijssen (1879–1943) describes in his memoirs how in the 1890s he had walked past the statue of Thorbecke, together with his father, who was a socialist shoemaker, and his younger brother Henk:

‘Take off your caps’, says father. ‘For that dead chap?’ Henk responds reluctantly. But father lifts his silk top hat and I take off my cap with deliberate ceremony – I had been through this greeting business before – and Henk obeys, only to be on the safe side. ‘Later, I'll tell you who this Thorbecke is’, says father, as before, ‘but for now you only have to remember he was someone to lift one's hat for.’Footnote 58

Written sources on personal encounters with the monuments are almost non-existent; yet this anecdote shows how a family from a working-class background paid respect to the statesman in bronze. It implies that Theo's (socialist!) father recognized the importance of the liberal politician. At the same time, both children were performing an act they did not completely understand.

Popular interaction in pictures

The transmission of the message behind the statues and memorials was not self-evident. While sociologists and anthropologists use interviews or participant observation to reconstruct the popular interaction with the monumental landscape, for historians this is not an option.Footnote 59 Written sources on the perspective from below are limited: ordinary citizens did not appear in the minutes of the official committees, and their behaviour and opinions are often voiced by others, as was the case in, for example, Schenkman's poetry.Footnote 60 In this final section, I will focus on visual sources and demonstrate how they can help us to tackle this methodological challenge. Depictions of the monuments show a variety of popular responses to the statues and memorials and therefore make us aware of the multilayered meanings and usages in daily city life. I will discuss two types of visual sources: illustrations, such as drawings, engravings and lithographs, versus the novel medium of photography. The first type mainly reflected the ideas of the initiators, while the second type – although not free from nineteenth-century values and genre conventions – gets us closer to everyday interactions in the city's streets.

The initiators took little effort to explain the monuments to the city dwellers. The only ‘educational material’ available were illustrations. The illustrations of the monuments were a souvenir of the festive ceremonies but also presented an ideal world: they instructed citizens on how to interact with the statues and how to behave themselves within this new public space. In a few cases, the illustrations showed only the statue or memorial itself; yet most of them also depicted city dwellers. This could be an artistic choice, for example, to emphasize the architectural dominance of the monument or to enliven the atmosphere in the picture. Yet there also seems to be an educational incentive: the people portrayed in the illustrations were most of the time gazing at and admiring the monument. Unfortunately, we know little about the manufacturing process. The drawings, engravings and lithographs were commercial products; shortly before and after the unveiling ceremonies, newspapers advertised prints in a wide price range. This practice suggests a market and a popular response.

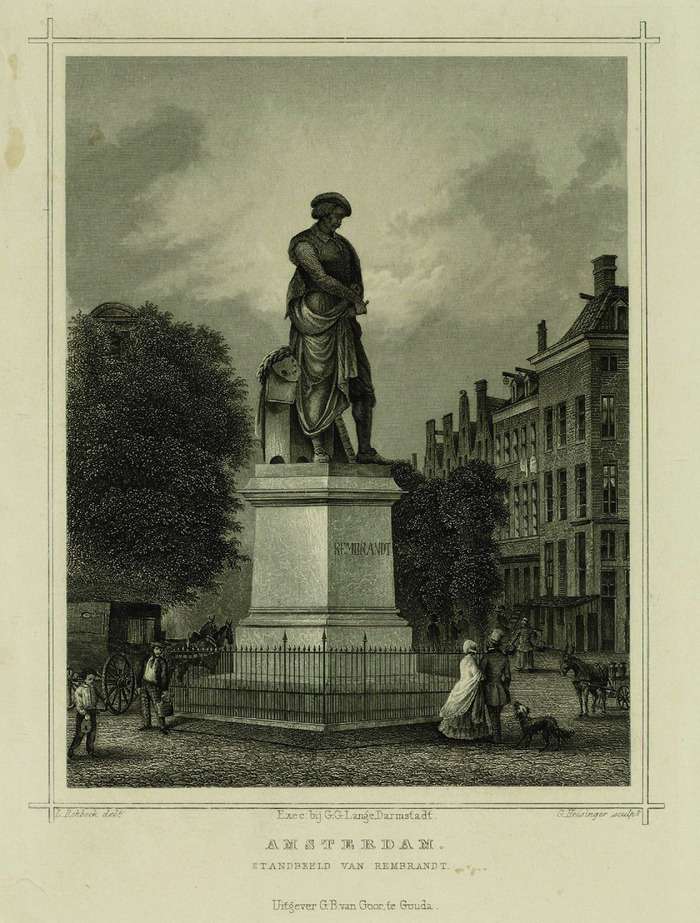

The message of admiration is central to most of the illustrations of statues and memorials in Amsterdam. The pictures repeatedly showed well-dressed passers-by looking at the monument, supposedly contemplating the higher (national) meaning of the represented figures or events. Figure 2 shows an 1855 engraving of the Rembrandt statue. The people portrayed appear to belong to at least the higher middle classes: the gentleman is wearing a top hat, the lady a pretty dress with a fine shawl. They might just have arrived in the carriage waiting on the other side of the statue. Only in the background do we spot a glimpse of common people: a maid is carrying two baskets or water buckets, a donkey-cart enters the picture on the left. Other illustrations of the Rembrandt statue show similar scenes: first and foremost, citizens from the middle and higher social classes halted at the statue and paid respect to the seventeenth-century painter.Footnote 61 The monument was depicted as an object that commanded respect and attention.

Figure 2: This engraving of the Rembrandt statue from 1855 shows city dwellers in admiration of the monument and was probably made for commercial purposes. Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Collectie Tekeningen en Prenten, 10097/010097003675, ‘Amsterdam. Standbeeld van Rembrandt’, G. Heisinger/G.B. van Goor, c. 1855.

This attitude was stimulated in real life by the appearance of a railing or small fence surrounding the statues. A railing established a proper distance between the monument and its onlookers. Requests by contemporaries to create a barrier express the concern to ensure that the statues were dealt with in a respectful way. In 1856, for example, the Dutch newspaper Algemeen Handelsblad published a suggestion by one of its readers to develop protective measures for the monument on Dam Square: ‘Some strollers would like to see the Monument of Concord surrounded with a railing, like the one surrounding Rembrandt, lest it be no further groped or damaged, as already is the case.’Footnote 62 It is not clear whether these requests were based on the actual reality of vandalism, a practice we unfortunately know little to nothing about for nineteenth-century Amsterdam, or the fear of city dwellers for potential damage to the monuments.Footnote 63 The railing not only kept city dwellers at a safe distance, but also directed their gaze: confronted with the fence the only possible way to perceive the monuments was to look at them, upwards and in admiration.

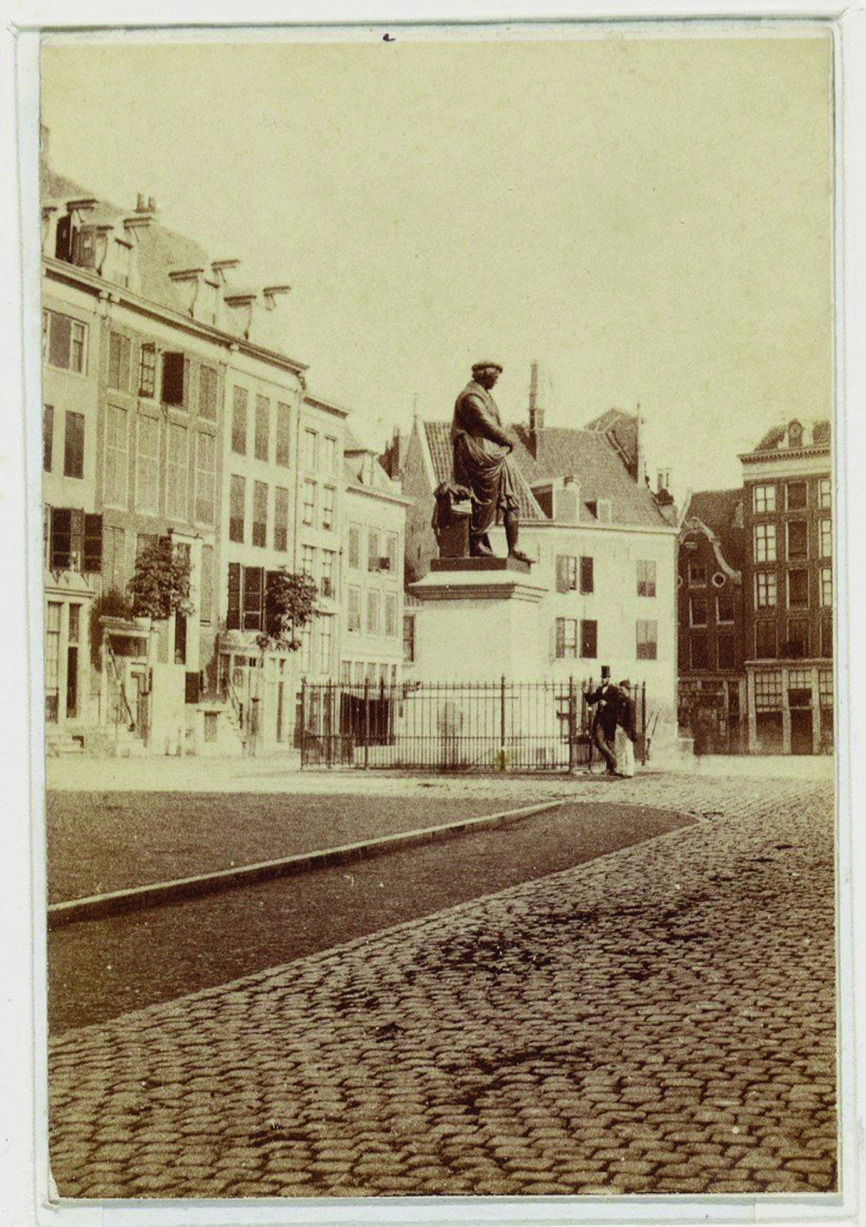

Photographs confirm this type of interaction. There are various examples of people posing in front of the statues and monuments. An undated picture of the Rembrandt statue shows how a man, neatly dressed and with top hat, and (presumably) his wife, deliberately took position in front of the painter (Figure 3). From the fact that this photograph exists, we can conclude that they at least thought the statue was worth noticing. In some cases, these people may have identified themselves with the ideas of the founding committees. It is also possible that they were tourists and the photographs were meant as a souvenir of their visit to Amsterdam. It is interesting to consider the idea of ‘intervisuality’ between these photographs and the above-mentioned illustrations: did these people pose in front of the statues as they thought they were supposed to do? The drawings and lithographs they had previously seen could have provided the inspiration for this new practice.

Figure 3: Posing in front of the seventeenth-century painter. Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Collectie foto-afdrukken, 10003/OSIM00001004537, ‘Rembrandtplein 12-2’, Pieter Oosterhuis.

In other cases, the posed photographs were reminiscent of a more emancipatory goal. In 1868, a group of artists and intellectuals positioned themselves in front of the statue of Vondel. The initiative for the statue was taken by a group of prominent Amsterdam Roman Catholics. They presented the seventeenth-century Vondel as the greatest poet of the Dutch Golden Age, a strategy similar to the one pursued by the painters who initiated the Rembrandt statue. In the photograph we see, amongst others, the Catholic architect Pierre Cuypers, who designed the pedestal of the monument, together with his son and spouse, and the Catholic writer Joseph Alberdingk Thijm, Sr, who had been involved with the plans for the monument. By letting themselves be photographed in this way, they claimed the Vondel statue as an important symbol of the politico-religious emancipation of the Roman Catholic community in Amsterdam.Footnote 64 We do not know of similar photographs of the other statues in the city.

In contrast to the lithographs, the photographs show us how not only people from the higher classes but also people with a working-class background (recognizable by their working-men's caps) self-consciously posed in front of the statues. An example of this is a stereo-photograph by the local photographer Andreas Rooswinkel (1838–1909) of a group in front of the statue of Vondel.Footnote 65 The picture dates from the 1880s and we see several men and boys dressed in outfits that belonged to the working or lower middle classes. They could be passers-by since the stereo-photograph was probably intended for the commercial market. An example of a posed portrait of city dwellers from a middle-class background is a picture of a group of children in front of the Sarphati bust, which was taken around the turn of the century. The girls are dressed in neat white dresses while the boys wear caps; the excitement triggered by the photo-moment is still visible in the nanny who is trying to organize the lively ensemble (Figure 4).Footnote 66

Figure 4: A group of children from the higher middle class and their nanny in front of the Sarphati bust. The photo was taken by the Amsterdam street photographer Jacob Olie (1834–1905) on 23 July 1896. Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Collectie Jacob Olie Jbz 10019/40074469, ‘Sarphatipark’, 1896.

The photographs clearly offer a more direct view on nineteenth-century reality than the (commercial) illustrations that were supposed to reflect an ideal world. The modernization of the city was a popular subject with both professional and amateur photographers who started to experiment with the new medium of photography from the 1850s.Footnote 67 Because of the development of new techniques and the improvement in materials and equipment, it became easier to roam the streets with a camera. Nineteenth-century Amsterdam had some famous street photographers, who produced a wide array of snapshots of the city.Footnote 68 Part of this photographic production was intended for the commercial market, as were the drawings, engravings and lithographs. Picture postcards proved to be especially popular.Footnote 69 These postcards often showed the monuments isolated from city life, in black and white or coloured afterwards in order to create a ‘realistic’ feel. Only at the turn of the century do the postcards start to show more inhabitants and city life.

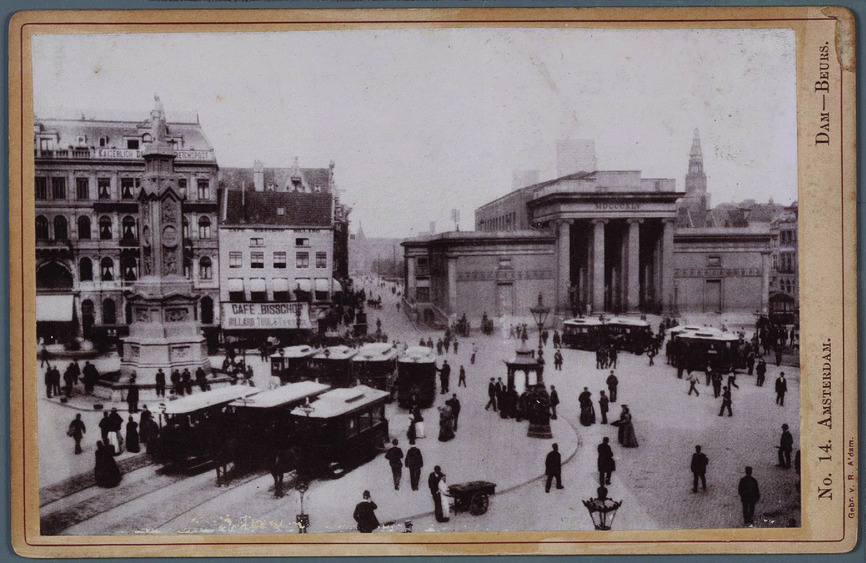

Most of the city dwellers that appeared in the photographs did not pose intentionally. This second category – in addition to the posed photographs – gives us a better understanding of the daily experience of the monumental landscape. As mentioned, the Rembrandt statue was placed on a market square. The maid and donkey-cart in the 1855 engraving already visualized the lower-class background of the location. Photographs of the nineteenth-century Botermarkt confirm this atmosphere. While the photographer focused his camera, an artisan and his customers who did business at the foot of the statue were distracted (Figure 5), or a man with a handcart crossed the square on his way to deliver his goods.Footnote 70 These street snaps stand in clear contrast to the drawings, engravings and lithographs: indeed, people did halt at the statue, but to practise their profession, sell their products or hang out with other people. In short, the monument was part of their daily routines.

Figure 5: Street life on the Botermarkt. A picture postcard by the local photographer, publisher and art seller Andries Jager (1825–1905). Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Collectie kabinetfoto's 10005/010005000433, ‘De westzijde van het Rembrandtplein’, A. Jager, 1867–72.

From the photographs, we can discern several usages of the monuments in daily city life. Some statues proved to be a magnet for commercial activities, in part because of the central location of these monuments, but this also had to do with their function as landmarks in the city. These practices were visible not only at the Botermarkt. The popular writer Justus van Maurik, Jr (1846–1904) immortalized the Jewish shoe polisher Isaäk, who offered his services at the foot of the monument on Dam Square: ‘At 8 am the trams and omnibuses arrive at Dam Square, and my business starts. I take my shoebox in my one hand; in the other I have a sign with tramway tickets. I shout out as loud as possible: “Tickets, gentlemen! Omnibus and tramway tickets!”’Footnote 71 Van Maurik wrote his story about Isaäk in 1881; yet already shortly after the unveiling of the monument on Dam Square in 1856, city dwellers began complaining about the nuisance caused by all kinds of merchants and their displays next to the monument.Footnote 72 These commercial practices are clearly visible in drawings and lithographs as well.Footnote 73

The monuments also served as an urban meeting point. Whereas the young Theo Thijssen learned how to treat the statue of Thorbecke with the utmost respect, others approached the monument in a different way. In the spring of 1896, the Amsterdam street photographer Jacob Olie (1834–1905) captured two working-class men resting casually against the railing surrounding the statue.Footnote 74 Two housemaids walked past; the men gave an arch look. Are we witnessing some flirtation here? Although this might seem a far-fetched conclusion – and the idea might indeed be more exciting than reality – other sources confirm the use of the statue as a romantic meeting point. For example, an advertisement in the lower- and middle-class newspaper Het Nieuws van den Dag from 29 April 1895 expressed a cri de coeur from an anonymous gentleman who had missed his appointment with a certain ‘Miss M.B.. . .Ma’ at 7 o'clock at the base of the statue. On these occasions, the statue by no means reminded the city dwellers of Thorbecke's liberal advancements for the country, but served as a hang-out instead.

Photographs of the monuments of Vondel and Sarphati show fewer city dwellers casually passing by. In contrast to the statues of Rembrandt and Thorbecke and the monument on Dam Square, these sculptures did not belong to principal (traffic) routes in the city. Both Vondel and Sarphati were placed in larger public parks and were thus shielded from the outside world: city dwellers did not come across these monuments on a regular basis but needed to pay them a proper visit. From the bust of Prince Hendrik, the popular brother of King William III (r. 1849–90), there are only a few photographs left; in these pictures, people are absent altogether. The memorial was placed in a small park opposite the newly built Central Station (opened in 1889). The busy spot promised to ensure public interaction, but we have no proof of this. This could perhaps point to a lack of popularity; the difficulties in raising funds to erect the memorial might have been an ominous sign.Footnote 75

The initial meaning of the Amsterdam statues and memorials faded over time and became replaced by other associations and usages. Here, a central location could also turn out to become a disadvantage in terms of popular awareness. The national monument on Dam Square was by far the most visible to both visitors to Amsterdam and its inhabitants. Every day, thousands of people would pass the statue, but did they also take notice of it? It appears that at the turn of the century, busy city life was taking up all the attention, as was remarked by a newspaper reporter:

The city dweller passes the monument, as he passes so many other things that appear common to him; and the stranger, he has other things on his mind. He has to see the Palace and the Nieuwe Kerk [New Church] and the Exchange and at the same time try to avoid a confrontation with other pedestrians and all the carts, carriages and trams.Footnote 76

With the expansion of the railway network in the city, the monument appeared to be suitable as a tram stop as well; we have seen how shoe polisher Isaäk sold his tramway tickets on the spot. A picture postcard of Dam Square around 1900 visualizes how about six carriages at a time were waiting for their passengers to mount or dismount the tram (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Picture postcard of Dam Square in the 1880s. Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Collectie kabinetfoto's, 10005/010005000036, ‘De Dam gezien naar de ingang van het Damrak’, Gebr. Van Rijkom, c. 1886–89.

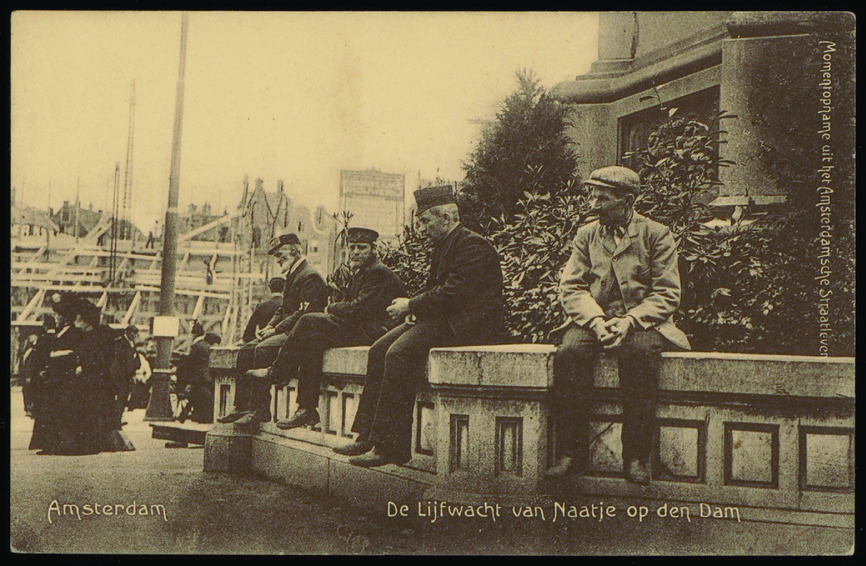

This example makes us aware of how the public statues and memorials were part of a constantly changing environment. The photographs of the nineteenth-century monumental landscape show how space could also lose its (nationalist) agency. The nineteenth-century public monuments started to experience competition from all kinds of other objects that made their appearance in the modern streetscape, from streetlights to post-boxes, clocks, advertisements and newspaper stands. Interactions with the statues and memorials could be in line with the intended meaning, like the young Theo Thijssen taking off his cap for the statue of Thorbecke, but city dwellers could also completely ignore the ideological and symbolical background. For the customers on the Botermarkt, the lover waiting for his date at the foot of Thorbecke, or the city dwellers mounting the tram on Dam Square, the sculptures in bronze or stone were only part of an urban décor (Figure 7). Unfortunately, pleas for saving the monument on Dam Square from the advancing modernization were in vain.Footnote 77 In 1914, the statue was dismantled and replaced by a railway track.

Figure 7: The – permanently empty – water basin of the monument on Dam Square was used as a hangout spot by elderly workingmen, a practice complained about by members of the Municipal Council. Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Collectie prentbriefkaarten 10137/3118/PBKD00441000035, ‘De Lijfwacht van Naatje op den Dam’, c. 1910.

Conclusion

In this article, nineteenth-century Amsterdam functioned as a case-study for the popular interaction with public monuments. This does not imply that Amsterdam as a capital was unique. A first exploration of the visual sources on monuments in other Dutch cities puts forward similar conclusions about the daily experience of the statues and memorials.Footnote 78 It would be interesting to extend this survey to other European capitals as well. The monumental landscape of nineteenth-century Amsterdam was limited to six statues and memorials; perhaps this relatively small amount of public monuments meant it was also more likely they became less visible in the constantly changing urban landscape? Capital cities such as Paris or Berlin have a more extensive and crowded monumental map; does this indicate that the ideological message came across more easily in these cities, or did the variety of visual information and competing stories result in even more confusion?

The study of nineteenth-century public monuments links the field of urban studies to the field of political history, nationalism studies and identity formation. Scholars have generally studied statues and memorials through an ideological lens: what was the central idea behind the monument and how was this expressed in the sculpture itself? The meaning of the public monuments, however, was negotiated in everyday life. I have demonstrated that a more socially oriented approach to public monuments is crucial for understanding their function in the urban community. Examining monuments from a street level enables the researcher to do away with the strict distinction between top-down and bottom-up perspectives. Thus, the interaction between the elite initiatives and experiences of ordinary city dwellers comes within sight.

The public monuments in Amsterdam were meant to celebrate important people and events, yet the popular responses show how the nationalist message was not always at the core of ordinary people's experiences. In contrast to the idea that statues and memorials transmitted competing messages, this article argues that their multilayered character should be the focus of investigation. The transmission of the ideas and ideology behind the statues and memorials was not self-evident, first of all, because the initiators took little trouble to get the city dwellers involved. Further research on the link between city dwellers’ social backgrounds and their interaction with the monuments would be valuable: the market vendors’ response to the Rembrandt statue clearly differed from the perception of the well-to-do residents of the nearby Herengracht. This can be explained by differences in people's frame of reference (how much did people know about the person or event that was represented) but also by the location of the monuments in the urban landscape (was the statue placed in a ‘new’ environment or did it take up spaces previously used for other activities). Both written and visual sources confirm that monuments sent a nationalist message but also functioned as practical landmarks. As such, the monuments were turned into selling points and meeting places or were used by city dwellers as public benches. As a consequence, it would prove difficult to keep the original meaning and ambition of the initiators present in the minds of passers-by.

How people actually perceived the statues and monuments and how they interacted with these new elements in the city are as important as understanding the symbolic value of the monumental landscape. The perspective from below therefore enriches our understanding of the role of the urban landscape in nineteenth-century nation building.