Introduction

Even a hasty trip to post-annexation Crimea is unlikely to see the visitor miss the many billboards showing Russia’s President Vladimir Putin as he – timelessly – reminds locals that “Krym. Rossiya. Navsegda” (“Crimea. [Is] Russia. Forever”). As Beissinger (Reference Beissinger2002) argued in reference to the process of nationalist mobilization in the late Soviet period, in Crimea the “seemingly impossible rapidly became the seemingly inevitable” between December 2013 and March 2014 (3). As soon as it became clear that then Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych had been toppled by the pro-European opposition forces of the EuromaidanFootnote 1, Moscow wasted little time before reacting. On February 27, 2014 the so-called “little green men”Footnote 2 took over the administrative buildings of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea in the regional capital city of Simferopol. Within the next three weeks they effectively neutralized all Ukrainian military bases on the peninsula and blocked the two points of entry to the region from mainland Ukraine (Armians’k and Chonhar). In a local referendum held on March 16, unification with Russia was supported by 96.77% of voters (Electoral Committee of ARC 2014); on March 18, 2014, the Russian government declared the Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol the 84th and 85th subjects of the Federation. Footnote 3

Due to the broader regional and global geopolitical significance of its actions, understanding and unpacking Russia’s role in the crisis has received the bulk of scholarly attention. Russia’s annexation of Crimea is often interpreted as the continuation of Moscow’s strategy to preserve control over the post-Soviet space (its “near abroad”) through various means (Toal Reference Treisman2016; Biersack and O’Leary Reference Biersack and O’Leary2014; Macfarlane Reference Mahoney2016; Rosefielder 2016). Academic analyses delve into the reasons for Russian engagement in Crimea (Ambrosio Reference Ambrosio2016; Sakwa Reference Samar2014; Tsygankov 2015; Malyarenko and Wolff Reference Malejacq and Mukhopadhyay2018; Treisman 2016; Teper Reference Toal2015; Menon and Romer 2015; Toal Reference Treisman2016; Wilson Reference Wolff2014; Plokhy Reference Prytula2015), the sources of its leverage (Hughes and Sasse Reference Hughes and Sasse2016), the discourses justifying Crimean annexation, the legal issues of its legitimacy (Allison Reference Allison2014; Hopf Reference Hopf2016; Laruelle 2015), or the link between the Crimean events and domestic Russian legitimacy and identity (Kolstø Reference Kolstø2016). We acknowledge that without the Kremlin’s backing turning the annexation of Crimea from a vague idea into an actual plan and then reality would have not been possible. However, we propose that a full understanding of the Crimean conflict needs to complement this perspective with an analysis of the relationships between Kyiv and Simferopol on the one hand, and between Simferopol and Moscow on the other in the lead-up to the ousting of Yanukovych.

To do this, we draw on the small, but important body of literature that specifically explores local Crimean issues. Knott’s insightful research on identity perceptions in the region prior to annexation, for example, reveals nuanced and complex views beyond superficial – and yet common – commentaries of Crimeans as pro-Russian or uncritically embracing Russian-ness (Knott Reference Knott2015). O’Loughlin and Toal (Reference Plokhy2019) draw on public surveys conducted a few months after the annexation to capture the Crimeans’ attitudes towards the process, showing that the action – disputed and contested internationally – drew on considerable local public support. Matsuzato’s article (Reference Matveeva2016) traces the domestic developments in Crimean politics prior to and during the Euromaidan revolution. D’Anieri (Reference D’Anieri2019), Sasse and Hughes (Reference Hughes and Sasse2016) and Hale (Reference Hale2015) embed Crimean politics in the broader inter-regional dynamics. Hale’s work is especially useful in that he accounts for the relations between Kyiv and Simferopol in terms of power dynamics and competitions between different power factions, something which we find in our own analysis too.

Fundamentally, two questions drive our enquiry: what circumstances made the annexation possible? What choices were available and made, and by whom, in Crimea? In this article we emphasise that there are multiple, if converging, origins to the phenomenon of Crimea’s exit from Ukraine. As we try and strike a balance between exclusively local bottom-up studies and more macro-level analyses, we afford greater space to local intra-elite dynamics, while recognising that it remains difficult, due to the paucity of data, to establish which type of agency (local, international) may have ultimately been determinative. Overall, we emphasize the importance of contingencies and local political agency in shaping the events of the late winter and early spring of 2014.Footnote 4

Specifically, we advance a two-fold argument. First, the power vacuum, a sudden and abrupt de-institutionalization of the political system into which the central Ukrainian government was plunged as a result of Yanukovych’s ousting, opened a window of opportunity for settling old scores and restoring “Crimean control” over the peninsula. This constituted a critical juncture, understood here as “relatively short periods of time during which there is a substantially heightened probability that agents’ choices will affect the outcome of interest” (Capoccia and Kelemen Reference Capoccia and Kelemen2007, 348, italics in the original). While the exact meaning of “relatively short periods of time” depends on the individual case, the three weeks constitute a sufficiently accelerated period of time. Junctures are critical because they “place institutional arrangements on paths or trajectories which are then difficult to alter” (Capoccia and Kelemen Reference Capoccia and Kelemen2007, 342). In other terms they trigger path-dependent effects which give rise to lasting legacies which would be difficult to over-turn or change. In these moments of “institutional flux” broader structural processes and constraints are relaxed and the range of possibilities widened. Change is one outcome, but is not a necessary condition – or outcome – of a critical juncture. What is important, as we show later in this article, is that plausible alternatives existed in the case of Crimea, including a new bargain (no secession) and (re-)incorporation into Ukraine.Footnote 5 These course of actions, had they been pursued, would have led to different outcomes, thus highlighting the lasting impact of the choices made in those crucial weeks.

Second, we show that such important instance of transformative institutional change did not happen in a vacuum, but rather was embedded in the historical context of regional dynamics between Kyiv and Crimea. Consequently, while decision-making in Moscow enabled annexation, we contend that the critical antecendent for Crimea’s secession to Russia has its origins in the erosion and ultimate failure of elite bargaining during 2010–2014.

The tradition of elite bargaining, which had kept Crimea stable and relatively quiescent throughout the post-Soviet period, collapsed as a result of Yanukovych’s appointment of his cronies to all essential governing positions in Crimea, thereby unsettling the local balance of power.

To unpack all these developments, first, we deploy process-tracing to revisit the series of events and decisions made between February 22 and March 6. Process-tracing is a useful method in critical juncture analysis because, as “a mode of causal inference based on concatenation” (Waldner Reference Williams2012, 66), it serves the purpose of accounting “for outcomes by identifying and exploring the mechanisms that generate them” (Bates, Greif, Levi, Rosenthal, and Weingast Reference Bates, Greif, Levi, Rosenthal and Weingast1998, 12). As we try and link decision-making with initial conditions to outcomes, process-tracing is especially well suited to evaluate competing explanations in the context of case study-based historical explanations (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2015; Bennett and Checkel, Reference Bennett, Checkel, Bennett and Checkel2014; Capoccia and Kelemen, Reference Capoccia and Kelemen2007). We complete our analysis of the 2014 critical juncture with an examination of the conditions that preceded it and a discussion of the historically plausible alternatives that existed at the time.

This requires us to discuss first the critical antecedents, defined here as “factors or conditions preceding a critical juncture that [ … ] combine in a causal sequences with forces operating during the critical juncture to produce divergent outcomes” (Slater and Soifer Reference Slater and Simmons2020, 252). Next, an analysis of agency and choices is made through a two-fold counterfactual argument demonstrating that local actors could have made other choices (“historically available, not just hypothetically possible,” Capoccia Reference Capoccia, Fioretos, Falleti and Sheingate2016, 92) and that had they made them this would have engendered important consequences, either in the form of institutional continuity or a different type of institutional change. To this end, we scrutinize the “near miss” after the Orange Revolution, to show that earlier crises led to different outcomes, and lastly the path not taken of a renewed grand bargain between Kyiv and Simferopol, and the reason behind its failure. In practical terms, we show that the politics of Crimea’s annexation needs to be embedded in both a critical juncture (regime change in Kyiv) and a critical antecedent (Yanukovych’s decision to marginalize the local Crimean elite politically and economically in favour of his cronies from the Donbas and the erosion of the political pact). Taken as a whole, the article offers a different perspective on the Crimean take-over, one that complements the current prevailing geopolitical accounts – from the outside-in – focused primarily on Russia’s actions with local and regional political dynamics. In the end, we show that the choices of local actors were geopolitically consequential.

This article is organized as follows. In the next section we provide a brief methodological note where we make our respective positionalities explicit. Next, we briefly highlight Crimea’s main political cleavages and potential for conflict. We then revisit scholarly debates on Crimean autonomy, before discussing centre-regions relations in post-Soviet Ukraine. Subsequently we shed light on the critical antecedent to the 2014 events and consider the fall of the Yanukovych regime as a critical juncture in the relationship between Kyiv and Simferopol, before turning to the paths not taken.

Methods, Ethics, and Positionality

Much remains obscure about the discussions and the timing of the decisions that led to Crimea’s annexation. We acknowledge that much is still not known. We triangulated different methods to cross-reference information and address the weaknesses inherent to each technique of data collection and verify the realibility of data. We relied on local media in our investigation. We selected Novosti Kryma (“News of Crimea”) because it is an independent local online news outlet. Established in 2003, Novosti Kryma provided daily and hourly newsfeeds of the developments in Crimea from December 2013 to March 2014. What sets it apart from other Crimean media outlets is that its only focus at the time was on factual reporting, rather than providing commentaries and opinion pieces. We supplemented this “live” feed with the reports from ATR, the local television channel reporting on Euromaidan in Kyiv and in Crimea and whose archived video reports were available after 2014. Founded in 2006, ATR broadcasts in Russian, Crimean Tatar, and Ukrainian (its main audience has traditionally consisted of Crimean Tatars).Footnote 6 It operated in Crimea until April 2015, when it was forced to close under Russian law and later resumed broadcasting in Kyiv. Other local media and TV channels such as Krymskaia Pravda, Krymskoe Ekho, Krym TV did not provide regular coverage of the events or delivered an explicitly pro-Russian narrative. Ukrainian national media operating in Crimea focused on reports from Kyiv only. We have reviewed the two national TV channels that were most watched in Crimea at the time (“Intern” and “1+1”), but they started to cover local events in Crimea only in February 2014, when the situation escalated. Prior to that there were no special reposts on Crimea; they only reported on events in Kyiv. After February 26, media channels in Crimea that were not pro-Russian were swiftly replaced by Russian national media. For example, the Chernomorskaya TV and radio company saw their frequencies reassigned to Russia 24. We also acknowledge that this is now changing and the local media ecology is considerably more constrained than during the time of our fieldwork, as Zeveleva reports in her analysis of the local media ecology (Reference Zeveleva2019). To supplement these sources we also used archived articles from Ukrainian national media such as Zerkalo Nedeli/Dzerkalo Tyzhnia (Mirror Weekly, a newspaper founded in 1994, a website-only news source since 2019, partly funded by western NGOs) and the UNIAN news agency (Ukraïn’ske Nezalezhne Informatsiĭne Ahentstvo Novyn), an independent information agency founded in 1993.

We also carried out field research in Kyiv and Crimea, primarily in Simferopol and to a lesser extent Sevastopol in 2015, 2016, and 2018. Altogether, 13 interviews were conducted with local journalists, government officials close to the decision-makers at the crucial time of 2013–2014, and the representatives of different local political movements involved in the 2014 events, including from the Crimean Euromaidan, anti-Maidan, and local self-defence forces. Field research in conflict zones, politically closed and politically dynamic and contested environments, confront the researcher with various ethical and practical/logistical challenges (Fuji Reference Fuji2010; Koch Reference Koch2013; Markowitz Reference McCorkel and Myers2016; Wood 2006). Crimea was no exception, although the extent it did varied for the two of us.

Conducting fieldwork in Crimea is not as hazardous as the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics in the Donbas, where the situation is currently unsafe for everyone. Therefore scholars have resorted to collecting data in other ways (Wolff Reference Wood2021). Violence in Crimea was limited in scale and time in February and March 2014. Yet, the political and research environment has closed in recent years, dissident voices have left, are repressed, or self-censor. Reflexive accounts on the researchers’ positionality and their relations with the field have long been present in anthropological (Chattopadhyay Reference Chattopadhyay2013), sociological (Wackenhut Reference Wackenhut2018) and geographical (England Reference England1994; O’Loughlin and Toal Reference Plokhy2019; Zhao Reference Zhao2017) scholarship, with political science slowly – but steadily – catching up, also in relation to the post-Soviet space (Matveeva Reference Menon and Rumer2017; Knott Reference Knott2019; Malejacq and Mukhopadhyay Reference Markowitz2016). Crimea’s political environment was in flux when we carried out our research. However, at the time of our field trips, key informants still resided in the region, which made our visits particularly instructive and worthwhile. Still, we and they were aware of the challenging environment, which included a surveillance state and a tendency to self-censor, as noted in much of the scholarship on fieldwork in conflict zones (Gentile Reference Gentile2013; Ryan and Tynen Reference Sakwa2020). However, as Fuji has shown, under otherwise extremely challenging circumstances it is the “meta-data,” namely the informants’ “spoken and unspoken thoughts and feelings such as rumours, body movements, silences, so material that is not clearly articulated in their stories and interviews” (Fuji Reference Fuji2010, 231), that offer cues to the researchers as to the informants’ own positions and views on a topic.

Our positions in relation to the ‘field’ and the residents of Crimea are different. Fumagalli, an Italian citizen, has visited Ukraine on various occasions since 2008, including Crimea in 2011 and 2012, followed by another in 2016. He has extensive experience in researching other conflict and post-conflict settings in the post-Soviet space (especially Central Asia), including disputed territories (Abkhazia, Transnistria, Nagorno-Karabakh). Similarly to other scholars that carry out research in contested regions (O’Loughlin and Toal Reference Plokhy2019), he also faced ethical and practical dilemmas. This is best illustrated in relation to the question of entry into Crimea, which was at the same time an ethical, logistical and ultimately also a legal challenge. An important aspect revolves around the position of privilege – a “matter of social power and political differentiation” (Kappler Reference Kappler, Ginty, Brett and Vogel2021, 422) - that international researchers often enjoy (McCorkel and Myers Reference Matsuzato2003). Fumagalli was aware that his visit to a contested territory could have been perceived and construed as de facto recognising and legitimising the annexation. Entering Crimea by airplane via Russia is currently illegal by Ukrainian law, but this is the only feasible way for non-Crimean residents to access the region.Footnote 7 At the same time, the very fact that being in Crimea would enable us to observe Fuji’s ‘meta-data’ (Fuji, Reference Fuji2010) tilted the balance in favour of a visit. This was neither an endorsement of Russia’s annexation nor an invitation to others to uncritically make a similar choice. It was a personal decision, involving serious trade-offs, and was taken after a lengthy and serious reflection.

Rymarenko is originally from Crimea and of mixed-Ukrainian-Russian heritage. As she holds Ukrainian citizenship, Rymarenko has been able to enter/exit Crimea via land corridors from the Ukrainian mainland, though in recent months exit has become increasingly challenging and bureaucratic. The feeling of researching “the home as field” bears strong resemblances to what scholars such as Zhao (Reference Zhao2017) and Chattopadhyay (Reference Chattopadhyay2013) have noted in their own work as the insider-outsider dilemma. Conscious self-reflection and recognition of one’s own identity and positionality while conducting fieldwork were especially important for her. While born and raised in Crimea she was aware of her identity as an insider and aware of the fact that interviewees would treat her as such. At the same time, having lived outside of Crimea at the time when the 2014 events occurred put her in a position of an “outsider” with regard to her research topic. While some scholars such as Chattopadhyay (Reference Chattopadhyay2013) reflect on the challenges to reconcile the insider-outsider perspectives, for the purposes of this research the dual identity appeared at advantage. As an insider, Rymarenko was able to get access to the region and draw on personal networks to access, secure the trust and gain the consent of the participants in Crimea and in Kyiv to be interviewed. Her insider identity was helpful in establishing a trust-based working relationship with the particpants and allowed them to feel comfortable and safe when sharing personally sensitive information and be open about their political beliefs and choices. Being an insider to Crimea but not an eye-witness of the researched events, Rymarenko was also perceived as someone in need of being “enlightened” about the local dynamics. At the same time, as an international researcher, she was also treated as an “outsider,” expected to report the “real story” through the reflections that participants shared with her as an insider. Understanding the context underpinning her own identity was helpful in interpreting the sources and material shared by interviewees in determining their choices, which also resulted in a more nuanced and context-sensitive interpretation of the critical antecedents and critical junctures discussed in this article.

We sought and secured informed consent from the informants, explaining our project, its aims (academic research, not journalistic dissemination) in as clear and accessible a language that we could. As others have also noted (Knott Reference Knott2019; Wood 2006), asking for written consent from participants in conflict zones or authoritarian contexts can raise suspicion among participants so we opted for oral consent. Overall, we sought to follow the best practices of ethical and reflexive research on peace and conflict, practicing what Koch calls “deep listening” in the form of intellectual humility and empathy towards informants (Koch Reference Koch2020).

Crimea: A Contested Land

The Crimean peninsula is geographically a single unit, home to a population of just over 2.2 million. However, under the Ukrainian Constitution (Art. 133) it encompassed two distinct administrative units: the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (Avtonomnaia Respublika Krym in Russian, or Avtonomna Respublika Krym in Ukrainian, and hereafter Crimea or ARC) – whose capital is Simferopol – and the city of Sevastopol, home to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. The demographics of the two units are slightly different, with ARC being much more diverse (58.5% Russians, 12.1% Crimean Tatars, and 24.4% Ukrainians), whereas Sevastopol is predominantly Russian (71.6%) with only 22.4% of Ukrainians.Footnote 8 Last, but not least, Crimea experienced the deportation of the Crimean Tatars by Stalin in 1944, and their return in the late Soviet period added to regional and ethnic cleavages.Footnote 9 It is worth recalling, however, that ethnic and linguistic differences do not overlap on the peninsula, which is predominantly Russophone.

Crimea’s potential for conflict stems from multiple factors. To summarize briefly, in light of the region’s relatively recent incorporation into Ukraine, a dispute quickly emerged around its legal status following independence; specifically whether the territory should be endowed with a particular autonomy (and the justification for this, ethnic or otherwise) and how territorial autonomy could be accommodated in an otherwise unitary state. The institution of Crimea’s autonomy was a Soviet legacy and was reaffirmed in a local referendum in 1991, prior to the disintegration of the Soviet Union. This allowed the Crimean elite to claim independence from Ukraine in 1992, which sparked a wave of pro-Russian mobilization in 1994–1996. The pro-Russian movement, however, was not sustained, and in 1998 the region returned to full Ukrainian jurisdiction with the status of autonomous republic. In other words, the 2014 push was not the first attempt to attain separation from Kyiv and the rest of Ukraine. Relations with Russia, historically, culturally, and politically close, also made Crimea’s status a domestic issue in the Russian Federation, when various political figures used it to enhance their position by stoking nationalist sentiments in Russia. Lastly, there was also the status of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol, a strategic asset for the Russian Federation and something that had been subject to acrimonious disputes between Russian and Ukrainian leaders. There was, basically, no shortage of combustible material for the outbreak of a conflict. All this notwithstanding, Crimea gradually stood out as an example of a “dog [of nationalism] that did not bark,” to use Ernst Gellner’s famous expression, remaining politically loyal to Kyiv until 2014.

Making Sense of Crimea’s Annexation: From Institutional Reproduction to Abrupt Change

Sasse’s seminal book embeds the Crimean question in the broader bargaining between the central and regional elite and identifies the political bargain between Kyiv and Simferopol as the central factor that helped preserve peace and stability in the region (Sasse Reference Skachko2007). Although the time-frame for Sasse’s work stops in the mid-2000s, her account, we believe, could also shed light on the run-up to the 2014 events. Giuliano’s emphasis on the role of cultural (Soviet nostalgia) and economic links to Moscow broadly fits this approach (Giuliano Reference Giuliano2018). Crimea’s exit from Ukraine is primarily explained through outside-in approaches, which, despite varying emphases on economic, cultural or other links, focus on Russia, the way it justified the intervention (Hopf Reference Hopf2016; Hale Reference Hale2018) and the broader geopolitical implications. There are few exceptions. Malyarenko and Galbreath (Reference Malyarenko and Wolff2013) place the Crimean question in the context of its relationship with the central government in Kyiv, but their analysis does not quite explore the role of Yanukovych’s cronies in Crimean politics and the economy and, furthermore, stops before the 2014 events. Matsuzato’s work (Reference Matveeva2016) stands out as the only study that scrutinizes the micropolitics of the Crimean annexation through a thorough reading of local politics. At the same time, attention very much revolves around the period between the fall of Yanukovych and the March 2014 referendum, thus missing out the crucial period preceding the Euromaidan. There are several reasons for this, including the fact that the ousting of Yanukovych constituted a critical juncture in the relationship between the centre and regions in Ukraine, with its effects extending well beyond Crimea, to the Donetsk and Luhansk regions (oblasti). It is precisely because of the political settlement (the elite pact) between Kyiv and Simferopol that it is important to examine what happened before. We therefore take this critical juncture as the departure point of our analysis, and walk our way back temporally to shed light on the conditions and the antecedents that paved the way for certain choices. This is consistent with a historical institutionalist tradition which acknowledges that choice points are defined by historical conditions (Capoccia and Kelemen Reference Capoccia and Kelemen2007, 347). In this respect, we find Slater and Simmons’s (Reference Kryma2010) work on the so-called critical antecedents especially useful as it enables us to shed light on what happened before the critical juncture (Slater and Simmons Reference Kryma2010, 887). At the same time, we find the work excessively structuralist, something which does not work well in the Ukrainian/Crimean context. Capoccia’s (Reference Capoccia, Fioretos, Falleti and Sheingate2016) approach is therefore preferable in that it explicitly acknowledges that in moments of social and political fluidity, the decisions of some actors are often more influential than those of others in steering institutional development. In moments of institutional rupture and change it is critical to scrutinize which options were available and which decisions were made – and when.

The Nature of the Kyiv-Crimea Political Settlement

Between 1992 and 1998 Crimea experienced a relatively short-lived period of pro-Russian mobilization, raising the prospect that the potential for conflict was turning into reality. By declaring independence in 1992 the Crimean authorities hoped to maintain control over the large local property of the Communist Party of Ukraine and the Soviet Union in the region (Skachko Reference Slater and Soifer1994). They saw their goal not in creating an independent state or reuniting Crimea with Russia, but in securing their access to power and preserving as much control over the region’s property as possible, especially in view of the upcoming privatization process. In 1992 the Crimean government issued a decree announcing its property rights over all state assets in the territory of Crimea (Zakonodatelstvo AR Krym Reference Zeveleva1992). According to Sergey Tsekov, Head of the Crimean Parliament in 1994–1995, the “pro-Russian orientation during the electoral campaign [of 1994] did not intend to secede from Ukraine [ … ] it meant the improved statehood [sic!] of Crimea and the development of closer cultural and economic ties with Russia” (Prytula 1994). Instead of really pursuing secession, the local elite therefore engaged in a long period of bargaining with Kyiv over the division of power between the region and the center. They used self-determination and independence as discursive tools to strengthen Simferopol’s bargaining position. This worked effectively and led to Kyiv making a number of concessions and ultimately striking a durable pact with the regional elite as well as between regional and national leaders regarding the status of Crimea. This is extensively discussed by Sasse (Reference Skachko2007). The elite pact found its consolidation in the institutional arrangement of Crimean territorial autonomy (the ARC), which secured a particular form of power-sharing between the central and local elite and ensured the region’s loyalty to the centre for about sixteen years (from 1998 to 2014). While Crimea was de facto fully subordinate to Ukraine in exercising its self-governance, the local elite were granted access to material (economic and political) resources by the central government, by virtue of being in charge of the Parliament of Crimea and the Council of Ministers of Crimea (the main governing institutions of the autonomous republic). This institutionally guaranteed access to power and resources was a key benefit that prevented local leaders from questioning the existing status of Crimea or raising any claims for secession.

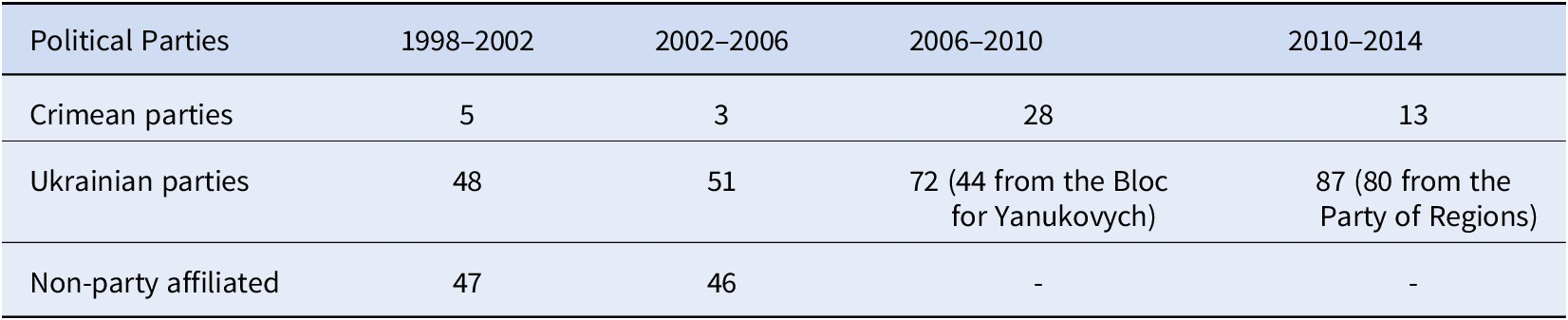

According to the political settlement inscribed in the 1998 Constitution of Crimea, the Parliament of Crimea (Verkhovnyĭ Sovet Avtonomnoĭ Respubliki Krym or Verkhovna Rada Avtonomnoï Respubliku Krym) was composed of 100 deputies elected for a five-year term (Art. 22). The Head of the Crimean Parliament was elected by the Crimean Parliament from among its deputies (Art. 29). This appointment did not require any approval from the central government. The chairman of the Parliament was also responsible for proposing candidates for the Presidium of the Crimean Parliament (a special body coordinating the work of parliament) (Art. 29, 30). These candidates did not require approval from the center either. Thus, even though the Verhovna Rada of Ukraine had the right to dismiss the Parliament of Crimea, the central government had little direct say, or even required formal approval over the nominees for key governing positions. The government of Crimea (Sovet Ministrov Avtonomnoĭ Respubliki Krym, Rada Ministriv Avtonomnoï Respubliku Krym) was also appointed by the Crimean Parliament independently of the center (Art. 35). The government or any of the ministers could only be dismissed by the decision of the Crimean Parliament. Candidates for the position of the Head of the Crimean Government (Prime Minister of Crimea) required the approval of the President of Ukraine (Art. 37), however, this approval was usually granted after unofficial consultations with the representatives of ARC and the position was normally given to a compromise local candidate. With the rare exception of the period between 1998 and 2010, the Heads of the Crimean Parliament, their Vice-Heads, and the Heads of the Crimean government were either born in, or made their political career in Crimea and thus were part of the local political networks. A long-term political settlement between the center and the region was preserved through these formal and informal institutional arrangements. Regardless of the political changes in the capital, the local elite in Crimea had institutionally protected means to preserve their access to power and resources. This translated into a “stability of cadres” and, crucially, into Simferopol’s political loyalty to the central government. During the early 2000s, then President Kuchma (1994–2004) could rely on the support of 85 deputies out of 100 in the Crimean Parliament. The head of this pro-Kuchma “Stability” fraction, Boris Deich, noted: “Crimea cannot live as a separate part of the state. Everything that is happening in Ukraine spreads to Crimea” (Kuzio Reference Kuzio2005). Ukrainian political parties have dominated the Crimean Parliament since 1998 (table 1), ensuing a strong connection between the region and the political processes in Ukraine.

Table 1. Distribution of Seats in the Crimean Parliament

Source: Central Election Commission of Ukraine (https://cvk.gov.ua/).

Crimea’s autonomy ensured that the local elite could reap political and economic benefits over the years. This arrangement worked until 2010, when Yanukovych became president. Eager to consolidate his power through centralization, he violated the power-institution compatibility of the Kyiv-Crimea elite pact, which led to the erosion of the center-region settlement and served as a critical antecedent to the revival of separatist claims in Crimea during 2013–2014.

Critical Antecedents: Crimea under Yanukovych and the Collapse of the Elite Pact

Yanukovych received 61.1% of Crimea’s votes in the first round of the 2010 presidential elections, and 78% in the second (Elections of the President of Ukraine (by regions) 2010). Yanukovych’s victory brought an inflow of new power groups into Crimea from the Donbas, the president’s own native region, politically well-connected and economically greedy. In Crimea these were called “Macedonians” (makedontsy) – a moniker for power groups from the cities of Makeevka and Donetsk. The marginalization of the Crimean elite in favour of new patronage groups from eastern Ukraine crucially undermined the pact of the center-region elite and paved the way for Crimea’s exit from Ukraine. The institutional settlement that allowed locals to preserve control over the region did not help either. President Yanukovych simply disregarded it, restructuring Ukraine’s governance structure around “a vertical of power” (vertikal vlasti). The seriousness of his intentions was confirmed by the fact that the during his first visti to Crimea as a President, he replaced all heads of the regional security services. A similar style was picked up by Vasiliy Djarty, the new Head of the Crimean Government, appointed by Yanukovych. Originally from Makeevka, Djarty headed the electoral committee of the Yanukovych’s Party of Regions (POR) in Crimea and was familiar with the local political context. He made sure that every local political group had a “slice of the pie” that is a place in the government that grw in size, with nine deputy ministers; in addition, he introduced two new ministries and two additional committees (Samar Reference Samar2010a). At that time, the balance of power in the new political establishment of Crimea still benefited the locals. Djarty brought with him only four outsiders (three vice-ministers and one minister), but he restated Yanukovych’s warning: “Those who aren’t able to follow the directions will be fired immediately” (Samar Reference Samar2010a). Given that Crimean ministers could only be dismissed by the decision of the local parliament, this statement signalled that Kyiv had no intention of respecting the established center-region institutional arrangement. Tensions between the center and the autonomy began to deepen from that moment. The conflict between the makedontsy and the local elite became so heated that it even persuaded traditional political rivals in Crimea to coalesce against the Kyiv-Donbas coalition. A good example of this was the replacement of the head of the Bahçisaray Regional Council in July 2010. The local elite backed the re-appointment of the acting head of the region, Ilmi Umerov. In an unprecedented move a Crimean Tatar candidate, an active supporter of the Orange Revolution and one of the leaders of the Crimean Tatar protest demonstrations, was supported by local members of the Party of Regions, the Communists, and even the main rival of the Crimean Tatars’ radical “Russian Unity” party (Samar Reference Samar2010b). Yanukovych preferred to appoint another candidate, however, despite the recommendation of Vasiliy Djarty, who had endorsed Ilmi Umerov for the post (Samar Reference Samar2010b).

The Party of Regions firmly consolidated its power in the region in the local parliamentary elections in November 2010, gaining 80 out of 100 seats in the ARC Parliament, with only eight seats shared by the local parties “Soyuz” and “Russian Unity” (five and three seats respectively) (Interfax-Ukraine 2010). The center-region power-sharing deal ceased to exist completely as Crimea was taken over by the “Macedonians.” According to local media estimates, the share of outsidersin the regional power structures reached 40% (Samar Reference Samar2010c). Moreover, in almost every local regional or city administration vice-heads or secretaries from Makeevka or Kyiv were appointed. Djarty was instrumental to the weakening of Crimea’s autonomy, de jure and de facto. In blatant disregard for Ukrainian laws and even for the decision of the Constitutional Court, he ended the practice whereby the heads of the local parliamentary committees served as members of the Government. This decreased the power of the parliamentarians to influence decision-making in the government, now composed of “Macedonians.”

After the death of Djarty in August 2011 his course was followed faithfully by Anatoliy Mohylyov, also from the Donetsk Region, appointed by Yanukovych as a new head of government. Mohylyov’s appointment was disappointing for the local Crimean elite who had hoped to see Vladimir Konstantinov as the new Prime Minister. Yet again Yanukovych preferred his own man. The President did not follow the constitutional procedures for this appointment. Crimea’s deputies received a phone call the day before the parliamentary session with the instruction to approve the newcomer (Zerkalo Nedeli 2011a). The institutional arrangement of 1998 that ensured the power sharing between the autonomy and the center even during the most turbulent times had collapsed. The distribution of power between the Kyiv-Donetsk group and the local elite did not change significantly under Mohylyov. He appointed some Crimean representatives to his government, but the decision-making process was firmly concentrated on him and coordinated from Kyiv. Marginalization was not merely political, but also – and crucially – economic. The economic interests of Yanukovych’s family seemed to become the main concern of Anatoliy Mohylyov as the head of the Crimean government. He began by granting about 8,000 hectares of Crimean seaside to the hunting organization “Kedr” founded by Yanukovych loyalists Yuriy Boiko (the Minister for Energy), Vladimir Demishkan (Head of the State Service for Automobile Roads), and Sergey Tulub (the governor of the Cherkasy region) (Zerkalo Nedeli 2011b). The hunting organization was registered in the same town as Yanukovych’s luxury residence “Mezhygorie” (Zerkalo Nedeli 2011a). Brothers Andrey and Sergey Klyuev (Donetsk businessmen and members of the Yanukovych administration) received 336 hectares of agricultural lands from the Crimean Prime Minister to develop their solar panels business (Censor.net 2012). Dmytro Firtash, the main sponsor of the Party of Regions, was able to expand his business empire to cover the entire territory of Crimea. To add to his chemical enterprises in the north of the region, Dmytro Firtash received a huge lime pit near Belogorsk and the land of all former military state farms in Crimea (Bystritskiy Reference Bystritskiy2012). The sea port in Yalta was taken over by Olexandr Yanukovych, that in Feodosia by Dmytro Firtash and in Sevastopol by Rinat Akhmetov. Simferopol airport was known to be controlled by Olexandr Yanukovych and Mykola Azarov (Samar Reference Samar2012).

The local elite were completely removed from power and prohibited from extracting economic benefits. In 2011, Crimean politician Leonid Grach, commenting on the state of the Crimean government noted: “This is not the government of Crimea, it is as people say “makeevskiy tsentral,” Footnote 10 centered around the acquisition, even expropriation of local assets and the elimination of the Crimean political and economic elite” (Fokus 2011). The Crimean Tatar leader Mustafa Djemilev described the center-region relationship at that time thus: “The current change of executive power in Crimea is happening because the positions are needed for ‘the kin’ of those coming from the Donetsk region. Many people working in the government including Crimean Tatars were asked to resign because people belonging to the ‘team’ took their positions” (Censor.net 2011).

After the death of Vasiliy Djarty and before the appointment of Anatoliy Mohylyov as the Head of the Council of Ministers, the local elite sought to persuade Yanukovych that the new Government of Crimea should also include locals (Vedomosti Reference Wackenhut2015). The appointment of Mohylyov was the last straw, and pushed the local elite to seriously consider an alternative to the unsustainable status quo. Rustam Temirgaliev, the deputy of the Crimean Parliament at that time, described the local political context in 2012:

Everybody was tired. If under Yushchenko we faced forced Ukrainization, under Yanukovych we hoped for some prospect. And it came to some extent but Crimean elite were still powerless – they did not impact any decision-making, because Crimea was governed firmly by the Kyiv-Makeevka power groups. For the Crimean political elite the desire was to quit in order to keep at least some level of influence over the political processes. They were saying: who cares if we are governed by Moscow or by Kyiv? At least in Moscow they are Russians.

(Vedomosti Reference Wackenhut2015)From that moment onwards, according to Temirgaliev, in a guise typical of disgruntled and out of favor elites, “they were waiting for a chance” to restore local control over the region (Vedomosti Reference Wackenhut2015). The Euromaidan provided the much-awaited critical juncture.

The Critical Juncture: The Fall of the Yanukovych Regime and Russia’s Intervention

As soon as the first public demonstrations erupted in the Ukrainian capital in late November 2013, the Crimean elite made their support for Yanukovych unmistakably clear. During the period between November 2013 and January 2014, local leaders were convinced that the position of the President was unshakeable and that he would be able to pacify the protests in Kyiv. The Crimean Parliament called on the central authorities “to use all possible means to restore peace and order in the country” (ITAR-TASS 2014). However, a warning shot was issued on December 12, 2013, when Crimean deputies declared that the autonomous status of Crimea would be under threat, should power shift into the hands of “the organisers of the colour revolutions” (Novosti Kryma 2013). Already in the early days of the Euromaidan uprising, the deputies of the Sevastopol City Council signalled interest in appealing to Moscow for sending a peacekeeping mission to interfere in the situation in Ukraine. The idea did not receive support back then, but in early December 2013 a delegation of Crimean deputies from Simferopol visited Moscow (Zygar Reference Zygar2016, 275). However, as long as the Yanukovych’s position remained strong, Crimea remained peaceful and free of disturbances.

The situation changed after January 20, 2014, when the first violent clashes took place between protesters and government forces in Kyiv. It became clear that Yanukovych’s position had weakened. Local leaders took this as an opportunity to challenge the power monopoly of the Kyiv-Donetsk patronage network and to claim back some political power. In January-February 2014 there was increasing confrontation between the Crimean Parliament headed by Vladimir Konstantinov, who represented the interests of the local elite, and the local pro-Yanukovych Government of Anatoliy Mohylyov. Konstantinov as a Head of the Parliament was consolidating parliamentary support for the resignation of the Crimean Mohylyov and his government and was prepared to put this decision to the vote once a critical mass for a positive outcome was secured (Vedomosti Reference Wackenhut2015). It is at this moment when Moscow intervened.

In mid-January, Crimea received the Russian delegation bringing the religious artefact “the gift of the magi.” One of the delegates was Dmitriy Sablin, deputy in the Russian State Duma and close friend and business partner of Rustam Temirgaliev. Through Temirgaliev, Sablin insisted on meeting Anatoliy Mohylyov and Vladimir Konstantinov to discuss the situation in Kyiv. Mohylyov declined to meet the Russian politician, while Konstantinov and Temirgaliev met with Sablin privately on around January 30 and according to Temrgaliev reached an understanding that Crimea would receive all the necessary support and protection from Russia should it be ready to claim higher autonomy from Kyiv. Even more so, a high probably of referendum for reunification with Russia was discussed in case of power change in the Ukrainian capital. In these circumstances, according to Temirgaliev, separatism with the backing from Moscow looked like a winning strategy by which the local elite could regain political control over Crimea regardless of the scenarios unfolding in the capital. Should Yanukovych retain power, calls for greater autonomy would be met in return for much-needed support. Were the opposition to attain power, a strong push for a further distancing from Kyiv would enhance the leverage of the local elite to maintain power.

The first call to strengthen Crimea’s autonomy came on February 5. The initiative was taken by Anatoliy Mohylyov himself, despite his close affiliation with Viktor Yanukovych. Mohylyov explained that “this [the call for greater autonomy] was not about separatism, but about proposals to change the Constitution of Ukraine to preserve the status of autonomy” (Trend Reference Tsygankov2014). An appropriate resolution was adopted by the local parliament on February 19, following the escalation of violence during the “Peaceful March” in Kyiv. The head of the Crimean Parliament, Vladimir Konstantinov, explained this resolution as an attempt to “specify and extend the rights of the autonomy” and to find “an optimal way for Crimea of staying within a united Ukrainian state” (Russkaia Planeta Reference Ryan and Tynen2014). During his visit to Moscow on February 21, 2014, Konstantinov emphasized that “Crimea remains the main foothold of the central power in the country” (Russkaia Planeta Reference Ryan and Tynen2014) However, in case of the collapse of the central government, the government of Crimea would only consider its own decisions as legitimate. When asked about the possibility of referendum for secession, he called it “unnecessary,” because “Crimea had sufficient ability to solve its own problems” (Samar Reference Sasse2014). These statements suggest that the Crimean leaders were primarily concerned with the state of center-region relations particularly in case of power change in the capital. Their calls for separatism were instrumental in influencing Kyiv, but at that point their action was not geared towards secession.The ousting of Yanukovych on February 22 marked a turning point for Crimea, when secession turned from a bargaining strategy against Kyiv into an actual strategy for the political survival of the Crimean elite. During Yanukovych’s rule Crimea’s local elite had grown increasing disgruntled with their political and economic marginalization, as engineered by the “Macedonians.” Under an even less sympathetic post-Euromaidan government, populated by, among others, Ukrainian nationalists, the likelihood of restoring the region-center power balance was minimal, but still a plausible scenario. When an urgent parliamentary session was called by Konstantinov for February 26 to gain support for holding a referendum on independence, only 43 deputies showed up, while the required quorum was 51 (Vedomosti Reference Wackenhut2015). The majority of parliamentarians did not support seceding from Ukraine but agreed to vote on the resignation of the Mohylyov’s government even after the quorum was finally achieved. The work of the Parliament was also paralyzed by the mass protests at that day, and the local elite were actively vying for more power. The debate was mainly about the new distribution of seats in the Parliament given that POR was out of the picture. According to a Crimean journalist attending the session, the “Russian Unity” party and Crimean Tatar group each demanded one third of the seats, with the rest shared among the new representatives coming from Kyiv to replace the existing administration.Footnote 11. Eventually, the Mejlis used their close connection to Kyiv, and demanded half the positions (Vedomosti Reference Wackenhut2015). Neither situation was in the interest of the local POR deputies, who would lose the balance of power to the center once again. Eventually, any prospect of striking a favorable bargain failed as the protestors headed by Mejlis stormed into the Parliament building trying to prevent the voting. This made the secession scenario even more desirable for those who wished to remain in power. The presence of Russian soldiers as a security guarantee removed the last hesitation. As a result, the destiny of Crimea was decided on February 27 after the Russian “little green men” had taken over the Parliament building. Parliament held a no-confidence vote against the Mohylyov government, loyal to Kyiv, and decided on a referendum on the status of Crimea to be held on May 25, 2014. The question agreed during that session was: “Do you support the independence of Crimea within Ukraine on the basis of treaties and agreements?” The decision was supported by 61 out of 64 deputies (Interfax.ru 2014). Other sources reported that fewer than 40 deputies were present at the session (Sobytiya Kryma Reference Socor2014).

What If?

If we take the claims of indeterminacy and contingency that define a critical juncture seriously, then we should be able to go to the full length of the study of “what happened in the context of what could have happened” (Berlin Reference Berlin and Gardiner1974, 176 cited in Capoccia, Reference Capoccia, Fioretos, Falleti and Sheingate2016, 93). In this section we consider two “what if” situations. One is a near miss, namely the outbreak of a crisis in the relations between Kyiv and Crimea in the immediate aftermath of the Orange Revolution in 2004, which subjected the elite pact to a stress test. This shows that even in times of (earlier) crises the possibility of institutional re-equilibration (as opposed to abrupt change) was not to be excluded. The other is a counter-factual in the form of the renewal of an elite pact through a new bargain between the Crimean elite and the new Kyiv authorities, which highlights the then historically available and plausible path not taken.

A “Near Miss:” Crimea after the Orange Revolution

A serious test for Crimea’s autonomy and Kyiv-Simferopol relations came in the wake of the 2004 Orange Revolution, when Viktor Yushchenko – who received a mere 15.4% of support in Crimea, was elected to the Ukrainian presidency (Elections of the President of Ukraine (by regions 2004). During his tenure in office, the fortunes of Crimea’s pro-Russian movement were revived in response to his somewhat nationalistic domestic politics and markedly pro-western foreign policy priorities. According to opinion polls carried out at the time, the number of Crimeans who considered Ukraine their motherland dropped from 74% in 2006 to 44% in 2008 (Razumkov Centre Reference Rosefielder2011). There was also a growing local perception of “forced Ukrainization” during that time, with around 75% of Crimeans either agreeing or strongly agreeing with that statement (Razumkov Centre 2008a). Another source of irritation came from an expansion in the use of the Ukrainian language in the media and education.Footnote 12 Crimeans were prohibited from using Russian language in administrative and judicial procedures (Matsuzato Reference Matveeva2016, 229). Further friction came as a consequence of Yushchenko’s decision to bestow the state honour of “Heroes of Ukraine” upon the leaders of the World War II nationalist paramilitary UPA (Ukraïns’ka Povstans’ka Armiia, Ukrainian Insurgent Army).Footnote 13 This situation was made worse by the central government’s decision that all regional authorities, including the Crimean government and Sevastopol city council, should organize public events in commemoration of the 65th anniversary of the foundation of the UPA in 2007. UPA members have traditionally been considered Nazi collaborators in Crimea. The decision sparked intense public protests. In response, local communists and pro-Russian political parties and organizations organized pro-Russian demonstrations to object to Yushchenko’s policies, including his perceived pro-western foreign policy (Left.ru Reference MacFarlane2007). In 2006, there were mass protests in several Crimean towns against the joint Ukraine-NATO military exercises in the Black Sea (Socor 2006). In 2008, the President also constrained the terms and conditions for Russian military presence in Sevastopol (UNIAN 2008). Yushchenko’s foreign policy orientation stood in stark contrast to Crimean political sensibilities, where – at the time – 80% of people were in favour of Ukraine joining the Union State of Russia and Belarus, and 77% were against Ukraine joining NATO (Razumkov Centre 2008b).

The loyalty of the local elite to the center was tested and shaken during that time. A serious test to the Kyiv-Simferopol elite pact was the nomination of the new head of the Crimean Council of Ministers in April 2005. Volodymyr Shklyar, nominated by Yushchenko for this position, arrived at the Parliament of Crimea even before the official recommendation of the President reached Crimean deputies. The surprise appointment of Volodymyr Shklyar clearly violated the official procedure established in the Constitution of Crimea (Articles 29 and 37) and the Constitution of Ukraine (Article 136) for the appointment of local Heads of Government. According to the official procedure, the recommendation for the post should have come from the Head of the Crimean Parliament who, however, did not initiate such a procedure. In this situation the recommendation letter from the President that followed Volodymyr Shklyar’s arrival was seen by the majority of local politicians as a form of inappropriate political pressure (Samar Reference Samar2005a). In an effort to ameliorate the situation, Yushchenko invited Boris Deich (Head of the Crimean Parliament) and Sergey Kunitsyn (Head of the Crimean Government) to Kyiv for a meeting. Kunitsyn, in a subsequent interview, clarified that the purpose of his trip to Kyiv was that “[he] wanted to show to Kyiv that Crimea was not a regular region but an autonomy and governors could not be changed single-handedly and without consultation” (Samar Reference Samar2005b). He agreed to step aside, however, when Yushchenko proposed Anatoliy Matvienko, Kunitsyn’s former colleague from the National Democratic Party, as the Head of the Crimean Government. Matvienko remained for only five months, after which the Crimean Parliament pushed for – and obtained – his resignation (Samar Reference Samar2005c). He was replaced by local politician Anatoliy Budiugov, the leader of Yushchenko’s “Our Ukraine” group in the Crimean Parliament. Burdiugov was born in Odessa but had lived and worked in Crimea since 1993 as the local head of the National Bank of Ukraine. Unlike Shklyar’s case, the appointment of Burdiugov was preliminarily agreed between President Yushchenko and the local political elite, something which smoothened his endorsement by the Crimean Parliament (90 out of 100 deputies voted in favor) (Samar Reference Samar2005c). Burdiugov tried to ensure that each local political group was represented in his “coalition government.” Burdiugov himself had six Deputy Ministers. In 2006 the “For Yanukovych!” opposition block secured 44 out 100 mandates in the Crimean Parliament, but the power still remained in the hands of the locals. After a week-long consultation between the Head of the Crimean Parliament, Anatoliy Hrytsenko (Party of Regions), and President Viktor Yushchenko in June 2006, a “compromise candidate” was found. The new Head of the Crimean Government, Viktor Plakida, was believed to be a personal protégée of Anatoliy Grytsenko, who had worked closely with Plakida in the early 2000s as the head of the city administration in Lenino, a small town close to Kerch. Prior to his appointment Plakida worked as a director of the Crimean Electricity Network. Not originally from Crimea, Plakida none the less turned out to be a strong supporter of Crimean autonomy. Following Burdiugov’s style, Plakida increased the size of the Government of Crimea even further by adding seven Heads of Parliamentary Committees. This arrangement ensured that each of the local political groups had access to power and the opportunity to extract political as well as economic benefits. Ensuring that all groups had some access to the spoils was vital to the survival of the political settlement.

In sum, during Yushchenko’s rule, the Crimean Parliament and Crimean Government remained under the control of the locals. Despite friction regarding cultural and foreign policy issues, the local elite remained politically quiescent, and no secessionist claim was advanced. The situation changed radically when Viktor Yanukovych came to power in 2010 and the power-sharing balance between Kyiv and Simferopol was violated.

The Path not Taken: A New Elite Pact

What if Crimea’s elite had not pushed for secession-cum-annexation and had instead bargained for a new pact with the new authorities in Kyiv? Establishing that there were historically plausible alternatives is essential in order to gauge the importance of political agency. There were two alternatives to Crimea’s incorporation into the Russian Federation on paper. The first would have been the route to independence. Thus, Crimea would have turned into another Abkhazia, seeking recognition and, at least formally, shying away from turning into another subject of the Russian Federation. We could not find any trace of an outrightly independentist discourse in the material we reviewed, nor reference to any key political actor advocating such position. This may have been for a number of reasons including the fact that the Crimean elite had been assured by Moscow that this scenario (a legal limbo as a de facto state) would not occur. For these reasons we discard this option as purely hypothetical. What was realistically possible was a new elite pact, which the Crimean elite entertained, and that Kyiv so belatedly sought to pursue after an initial series of blunders which eventually set a course on a wholly different political trajectory.

The reaction of Kyiv to the situation in Crimea in late February and early March was hasty and disorganized. The decisions of the central authorities limited the opportunity to negotiate a new elite pact with the region. On February 24, the day after the Verhovna Rada of Ukraine assumed responsibility for the country, a draft resolution was registered proclaiming the dissolution of the Crimean Parliament on the grounds that it “systematically violated the laws of Ukraine” and that “its statements contributed to the development of inter-ethnic confrontation” (Novosti Kryma 2014a). The resolution called for an unplanned election to be held in May 2014. This move sparked an immediate reaction from the Crimean elite. Konstantinov called this decision “groundless and illegal” (Novosti Kryma 2014b). The Presidium of the Crimean Parliament issued its own statement on February 25 where it accused Kyiv of “exercising pressure and blackmailing the deputies” additionally arguing that “they [in Kyiv] do not understand … threats will only lead to political dead end, increase confrontation in the society and between the centre and regions” (Novosti Kryma 2014c). To some extent this political pressure from the center was effective. Anatoliy Mohylyov tried to negotiate with the representatives of the local pro-Russian movement and self-defence units on 23–24 February, arguing that Crimea should follow the decision of the Verhovna Rada and hold elections in order to consolidate local power and to be able to negotiate with the center.Footnote 14 Private communication continued between Kyiv and the local deputies, many of whom were reluctant to attend the Parliamentary session on February 26 concerning the future status of Crimea, and openly stated that they would refuse to vote on this issue.Footnote 15

The Crimean case was also debated in the Ukrainian Parliament on February 26 when the buildings of regional administrations in Simferopol were controlled by armed groups. Crimean representatives in the Ukrainian Parliament, Vitalina Dzoz, and Lev Mirimskiy, claimed that the region was merely reacting to the decisions of Kyiv adopted on February 24 designed to revoke the law that granted the Russian language official status in Crimea and the decision to dissolve the Crimean Parliament. Merimskiy stated that a peaceful resolution was still possible, however “if Crimea were heard” (STB 2014). A number of reassuring statements from the Ukrainian deputies followed, including that by Oleg Tyagnybok, the head of the Ukrainian nationalist “Svoboda” party, assuring that Crimea would maintain its autonomous status according to the Constitution and that it would not be deprived from the right to speak Russian language. The reassurances from the center came too late, however, as Russian forces were already taking over the region. Further attempts by Kyiv to negotiate with the Crimean leaders were unsuccessful. On February 28 Petro Poroshenko came to Crimea trying to promote the idea of a roundtable between the representatives of Crimea and Kyiv (UNIAN 2018). He was not allowed to enter the building of the Crimean Parliament. Similarly, the Crimean representatives refused to meet with Sergey Kunitsyn, the newly appointed Permanent Representative of the President in Crimea (Insider 2014). On March 4, the deputy of the Verhovna Rada of Ukraine, Nestor Shufrich, reported that an agreement had been reached with the leadership of Crimea on the prospect of amending the Constitution to extend the rights of the autonomy (Korrespondent 2014). Sergeĭ Aksenov, who had already been elected as the new Prime Minister of Crimea contradicted this statement, however. He claimed that “there was nobody to cooperate with, they [Kyiv] do not need it, they are now busy re-distributing power and money” (Stringer Reference Teper2014).

Alongside the offer of dialogue, Kyiv continued to exert pressure. At the meeting of the National Security and Defence Council about the situation in Crimea on February 28, 2014, Oleksandr Turchinov tasked the Head of Security Services to arrest Sergeĭ Aksenov and Vladimir Konstantinov and other separatists (UNIAN 2016). Kyiv was constrained in taking actual measures, however. According to the information presented at the Council meeting, the majority of the local security services, military and the special units were not ready to take orders from the centre (UNIAN 2016). On March 4 the Security Service of Ukraine issued official warnings to seven people from the Crimea, Luhansk, Donetsk and Kharkiv regions, suspected of undermining the territorial integrity of Ukraine (Novosti Kryma 2014d). The next day (March 5, 2014) the court in Kyiv made a decision to arrest the leaders of Crimea (Dumskaya.net 2014). On March 6 the Crimean Parliament decided to hold a referendum regarding the future status of Crimea on March 16, this time adding a question about joining the Russian Federation. In the same statement it requested that Moscow start the procedure of taking Crimea (and Sevastopol) as its federal subjects. In response, the Ukrainian Parliament immediately initiated a decision to dismiss the Crimean Parliament. As Matsuzato notes (Reference Matveeva2016), the local elite changed the referendum question following reassurances from Moscow that Crimea would not turn into another unrecognized republic, but would become a full and fully recognized part of Russia and receive appropriate financial support. Vladimir Konstantinov, however, explained that the Parliamentary decision to join Russia was a reaction to the situation in mainland Ukraine: “We do not see anything constructive from Ukraine, nor do we see any dialogue. Any dialogue is used to win time for scandalous decisions. By these decisions they push us out of the country. They do everything for us not to become the members of the community they want to create” (Novosti Kryma Reference O’Loughlin and Toal2014e). What was “scandalous” according to Konstantinov was the court’s decision to arrest the leaders of ARC (Novosti Kryma, Reference O’Loughlin and Toal2014e).

Some of our interviewees also referred to the fear of reaction from Ukraine as a primary reason why the local authorities hasted to finalize the reunification with Russia through a referendum. It was very well understood by the separatist leaders that the “window of opportunity” was offered not so much by the presence of the Russian military, but by the power vacuum in Kyiv at that time. As one of the interviewees stated, “back then there was not much trust in Russian army, because they could not intervene without an order [from Moscow].”Footnote 16 According to Aleksey Skoryk, “The only thing they [separatist leaders] were afraid of is that Kyiv would become stronger, or that something might happen, that Crimean politicians will change their mind.”Footnote 17 Another interviewee confirmed that “while they [had] all this chaos [in Ukraine] we can take decisions, because afterwards we might not get this possibility. We could not control all of Crimea and for long when being part of Ukraine. We had to take the decisions fast.”Footnote 18

Even though in reality Kyiv was restrained in taking active measures in Crimea, the statements made by Konstantinov and Aksenov suggest that the reaction of Kyiv had an impact on the political decisions made in Crimea during the critical period in February and early March 2014. Most interviewees agreed that if Russia had not intervened, the bargaining between Kyiv and Simferopol would have continued, and some kind of political and possibly institutional settlement would have been achieved. When separatist leaders faced the choice between criminal charges from the Ukrainian side and security guarantees from the Russian side, however, their choice was obvious.

Conclusion

Russia’s annexation of Crimea was as dramatic an instance of institutional change in the life of post-Soviet Ukraine and, by extension, the Russian Federation, as there has been since 1991. This is comparable and perhaps exceeds Russia’s recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in August 2008, because, on the one hand, Georgia had learned to live without those two regions for most of the post-Soviet period and, on the other, the Crimea crisis left the post-Cold War international order in splinters and arguably constituted the nadir of Western-Russian relations in recent decades.

Whilst acknowledging that there are multiple separate origins to Russia’s annexation, in this article we have sought to rebalance the current scholarly focus away from great power politics and the role of Russia towards a greater appreciation of the local drivers of Crimea’s annexation. This has allowed us to highlight and revisit the erosion and, ultimately, the failure of elite bargaining between Kyiv and Simferopol. The political settlement that kept Crimea stable from 1998 onwards began to erode during the pro-Russian Yanukovych presidency, not after the success of the Euromaidan. The two are closely related, but the former is a critical antecedent to the latter. The post-Euromaidan abrupt de-institutionalization in Ukraine created a power vacuum in Kyiv which, in turn, persuaded Crimea’s political elite that the region’s time in Ukraine was over. As often before, politics in Ukraine turned out to be regional. As Sasse aptly put it, Ukraine revealed itself once more as a “state of regions” (Sasse Reference Sasse2001). This time one of its regions dramatically exited the state at a moment of heightened vulnerability. The lead-up to Crimea’s annexation serves as a reminder of the importance of elite infighting and the reconfiguration of power dynamics and pyramids (Hale Reference Hale2015). Our analysis shows that out-of-favor local elites successfully lobbied the Kremlin for support as a back-up plan to a possible overthrow of Yanukovych, starting from December 2013 onwards (Zygar Reference Zygar2016, 275–281) as they pursued an exit from Ukraine and entry into Russia. Despite the existing structural constraints they still considered the negotiation of a new elite pact with Kyiv to be a realistic option until Russia’s military involvement made it impossible. Following the long-heralded opening of the bridge connecting Kerch to Russia in 2017, Crimea is now physically connected to the Russian mainland. New airport terminal buildings in Simferopol, energy plants in Simferopol and Sevastopol, and the massive construction of the brand new “Tavrida” highway connecting Kerch with Sevastopol, are very visible reminders of the full display of Russia’s infrastructural power. Navsegda?

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Kristin A. Eggeling and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful and valuable comments to earlier drafts of this article.

Disclosures

None.