Introduction

NHS Talking Therapies services, for depression and anxiety (TTad; formerly Improving Access to Psychological Therapies, ‘IAPT’) are the predominant providers of primary care mental health treatments within the UK. Talking Therapies services receive over 1.8 million referrals annually, with 1.2 million entering evidence-based treatment for common mental health problems (NHS Digital, 2024). Central to the TTad stepped care model is the Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner (PWP) role, delivering low-intensity (LI), high-volume assessment and interventions at Step 2. Guidance recommends LI interventions to consist of 6–8 structured sessions (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022); research suggests the optimum dose of low-intensity treatment is 4–6 sessions (Delgadillo et al., Reference Delgadillo, McMillan, Lucock, Leach, Ali and Gilbody2014). In practice, clients are typically offered between 4 and 6 sessions, and nationally clients attend an average of 4.6 appointments (NHS Digital, 2024). These LI treatments intended for mild to moderate depression or anxiety are characterised by briefer (∼30 minute) contacts with a clinician (or alternatively email/online contact), fewer overall appointments relative to traditional talking therapies; and by a predominantly psychoeducational approach supported by written or online resources (Ruth and Spiers, Reference Ruth and Spiers2023). Step 3 high-intensity (HI) interventions (predominantly CBT) are indicated for more complex or severe presentations, and clients who have not responded at Step 2. The initiative and stepped care approach was developed to accommodate individuals with mild to moderate depression and anxiety, and therefore the training curricula for PWPs are focused on these presentations (Clark, Reference Clark2011).

Despite the many strengths of the Talking Therapies service model and workforce, treatment is not currently optimised: approximately 50% of referrals do not reach recovery whilst accessing the service (NHS Digital, 2024). One possible explanation for this may be higher rates of severity and complexity than the service and workforce were originally intended to support (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Iqbal, Airey and Marks2022). In particular, screening tools estimate between 69 and 81% of Talking Therapies clients likely score above the clinical threshold for personality difficulties (problems managing their relationships, emotions and identity); and are 30% less likely to reach recovery at Step 3 (Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Wingrove and Moran2015; Mars et al., Reference Mars, Gibson, Dunn, Gordon, Heron, Kessler, Wiles and Moran2021). Across Steps 2 and 3, a greater number of personality difficulties predicts poorer outcomes, even when adjusting for intake severity, number of treatment sessions and demographic status (Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Wingrove and Moran2015). PWPs deliver care in high volume, and may have as many as 45 individuals on their caseload at any one time (Ruth and Spiers, Reference Ruth and Spiers2023); and up to 36 of whom may present with personality difficulties based on prevalence estimates in TTad settings. For most TTad clients, these difficulties are probably mild, or restricted to certain situations or contexts (see ICD-11 spectrum framework for personality disorders; Bach and First Reference Bach and First2018); but can commonly include frequent changes and difficulties regulating emotions; difficulties managing relationships and conflicts (which may not be fully observable at an initial assessment); and unclear or frequently shifting sense of self. Central to suitability for PWP interventions, and TTad support more broadly, is a primary problem of depression or anxiety which will form the focus of treatment. However, concurrent personality difficulties can create barriers to clients fully engaging with PWP interventions. For example, their mood and sense of the main problem may change from session to session, making it challenging to maintain focus on a specific intervention; it might be harder than usual for a clinician to understand their client, and be understood, making it harder to contain sessions within a 30-minute appointment; or clients may find being emotionally activated is a barrier to carrying out home practice. The heightened levels of complexity found in this setting may result from those involved in initial triage of clients (predominantly PWPs) not being trained to identify characteristics of complexity; equally this may be a result of pressures on assessors to meet access targets (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Iqbal, Airey and Marks2022). Furthermore, complexity often emerges over time, and interpersonal difficulties, for example, may not be evident until the therapeutic relationship starts to become established. Given the likely number of clients with these difficulties, and the kinds of challenges this raises for PWP working, training focused on understanding these difficulties and working with these clients is urgently needed.

Despite the high estimated prevalence of concurrent personality difficulties in TTad settings, there is a paucity of research exploring this issue; and on the potential impacts on service delivery. Qualitative research has explored clinician and patient views from TTad settings in the North West of England. TTad clinicians report feeling unskilled and overwhelmed when working with clients with concurrent personality difficulties and describe challenges in ‘maintaining control’ over sessions; although those that adopt more flexible treatment approaches were less likely to report feeling out of control (Lamph et al., Reference Lamph, Baker, Dickinson and Lovell2019). Consistent with this, clients with these difficulties valued more flexible/personalised approaches and described positive experiences as being characterised by a strong therapeutic relationship, whereas more structured or inflexible approaches were considered less acceptable (Lamph et al., Reference Lamph, Baker, Dickinson and Lovell2021). Practitioners noted a continuum of severity and viewed those at the milder end more likely to benefit from Talking Therapies treatments; but highlighted that their core training curriculum should include focused teaching on working with this group in their care context (Lamph et al., Reference Lamph, Baker, Dickinson and Lovell2019). Recent updates to clinical guidance for this client group recommend adopting a tailored approach, including assessment of interpersonal difficulties and addressing these during treatment for depression (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022). However, personality difficulties/disorders continue to be poorly understood by healthcare professionals and are linked to stigma and unequal access to care (Lamb et al., Reference Lamb, Sibbald and Stirzaker2018; Ring and Lawn, Reference Ring and Lawn2019), including in the NHS Talking Therapies context.

In other settings, educational interventions have been successful in improving workforce attitudes towards personality disorders; and have also improved staff burnout (e.g. Davies et al., Reference Davies, Sampson, Beesley, Smith and Baldwin2014; Dickens et al., Reference Dickens, Lamont, Mullen, MacArthur and Stirling2019; Finamore et al., Reference Finamore, Rocca, Parker and Blazdell2020). The broader mental illness literature also shows stigma can be reduced by strengthening continuum beliefs (Tyrer et al., Reference Tyrer, Seivewright, Ferguson, Murphy, Darling, Brothwell, Kingdon and Johnson1990). However, extending the core curriculum as proposed within the qualitative literature would not impact the existing TTad workforce knowledge and skills. A pragmatic and low-cost opportunity to disseminate training to the existing workforce is via Continuing Professional Development (CPD) workshops, as a majority of services routinely protect time for their staff to attend CPD and also fund external speakers to facilitate it, to support their continued registration.

The current research

PWPs are typically the first clinician contact in TTad services and PWP assessments are central to client triage within TTad services – often determining whether a client receives Step 2 or 3 treatment or is referred/signposted to a different service. In order for characteristics of complexity, such as personality difficulties to be considered within this triage process, PWPs must be able to recognise these difficulties; understand how they may impact treatment within their care context; and with appropriate supervision determine suitability for Step 2 treatment. PWPs also need to be trained to manage features of complexity that may not be initially evident, such as interpersonal difficulties. To facilitate person-centred care, PWPs would also ideally be skilled in tailoring low-intensity depression and anxiety treatments in the context of personality difficulties, for those clients who fall within the Step 2 remit. However, highly structured PWP interventions require careful thought about how treatment can be appropriately tailored for these clients, compared with more flexible HI approaches, to ensure fidelity to the core LI protocols is maintained.

To address this problem, a High-Intensity Therapist (HIT) workshop with similar aims around enhancing practice in the context of personality difficulties (see Warbrick et al., Reference Warbrick, Dunn, Moran, Campbell, Kessler, Marchant, Farr, Ryan, Parkin, Sharpe, Turner, Sylianou, Sumner and Wood2023) was adapted to meet the specific needs of the PWP workforce.

The current research therefore describes a co-development process to adapt the HIT workshop and presents an audit of feedback from piloting this workshop in a single Talking Therapies service.

The present audit aimed to explore feasibility, acceptability of the workshop and preliminary proof of concept by: (1) evaluating PWP engagement with the workshop; (2) exploring PWP feedback on the workshop; (3) exploring if the workshop improved PWP confidence to undertake assessments, and deliver depression and anxiety treatments in the context of personality difficulties; and (4) exploring PWP attitudes towards working with this client group in TTad settings.

Method

The intervention

The workshop was adapted from the HIT workshop described in Warbrick et al. (Reference Warbrick, Dunn, Moran, Campbell, Kessler, Marchant, Farr, Ryan, Parkin, Sharpe, Turner, Sylianou, Sumner and Wood2023) through a co-design process involving an academic-PWP (L.W.), a Senior PWP (T.L.) and a Lead PWP; and was then refined based on PWP delegate feedback. The HIT workshop was co-developed alongside experts with lived experience, and a PPI member from LW NIHR fellowship was consulted during the development of this PWP workshop (see Section 1 of the Supplementary material for a detailed comparison of the two workshops).

The academic-PWP was approached by the service to offer a comparable training for PWPs following receipt of the HIT workshop for their HIT workforce, due to their involvement in the HIT workshop development and evaluation and PWP professional background. The Lead PWP was responsible for arranging workforce training as part of their Lead PWP role, and was responsible for liaising with the Clinical Team Lead to ensure messaging around client suitability and tailoring of care was consistent with broader service policy. The Senior PWP was invited to contribute due to extensive experience in the PWP role and in training and supervising PWPs from across all levels of experience. All three PWPs undertook this project within the scope of their existing roles, and none received any additional payment for work related to this project. None have any conflicts of interest to declare.

The 1-day interactive online workshop followed three key themes: (1) Psychoeducation about personality difficulties; (2) Enhancing LI-CBT for depression and anxiety in the context of personality difficulties; and (3) Highlighting the importance of and building good PWP self-care when working with more complex clients. The original HIT workshop is informed by the CBT evidence base on how to adapt CBT for complex cases and personality disorders (e.g. Beck, Reference Beck2011; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Davis and Freeman2015; Davidson, Reference Davidson2007; Newman, Reference Newman2013). However, as no comparable guidance exists for adapting LI-CBT in the context of complexity, clinical expertise was used to adapt the most relevant concepts for PWP practice (in line with the principals of evidence-based practice; Howard and Jenson, Reference Howard and Jenson2003). Consensus was needed across the three PWPs that ideas and examples were consistent with LI working principles in order for inclusion in the workshop. The intention is to support PWPs to maintain fidelity to their protocols and LI frame while working with this client group, rather than leading to unhelpful therapist drift.

The training was initially co-facilitated by a clinical psychologist (B.D.) who developed and facilitates the HIT workshop alongside an academic-PWP (L.W.), before transitioning to two PWP facilitators [an academic-PWP (L.W.) and Senior PWP (T.L.)]. The structure of the workshop follows the declarative-procedural-reflective (DPR) model (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006) of CBT supervision and the COM-B model (Michie et al., Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011) of behavioural change, involving a mixture of didactic teaching, group reflection, role play illustration and role play practice.

The objectives of Theme 1 are to build a dimensional understanding of personality disorder/difficulties in line with the ICD-11 framework (Bach and First, Reference Bach and First2018); aiming to reduce stigma towards working with these clients and inaccurate assumptions that they cannot benefit from LI interventions for depression and anxiety. The pros and cons of diagnosis and labelling of personality difficulties/disorders are discussed and PWPs are encouraged to exercise caution around the language used to describe associated difficulties in the context of significant stigma associated with the personality disorder/difficulty labels. Updates to clinical guidance are shared, along with implications for practice as a PWP in TTad settings. For example, individuals with a historical diagnosis of personality disorder should not be routinely excluded from TTad services; and suitability should be individually determined by: considering if the primary presenting problem falls within the depression and anxiety remit of TTad services; and the current severity of personality difficulties (including whether these features can be safely managed in a primary care out-patient setting). Those with depression or anxiety in the context of more severe personality presentations will likely be more appropriately supported in secondary care or specialist services, rather than in primary care TTad settings. Where individuals meet clear diagnostic threshold for personality disorder, and resolving these difficulties needs to be the primary focus of intervention, TTad services are not suitable to meet this need and alternative treatment settings should be considered.

In line with the core PWP curriculum, the training explicitly highlights that PWP assessments and self-report measures are not intended to, nor expected to diagnose mental health problems – including personality disorders. Rather, the focus is on building PWP skills to recognise key difficulties in emotion regulation, managing interpersonal relationships and sense of self in clients, and the severity, frequency and complexity of these difficulties. Training then focuses on how PWPs might use this information to consider the suitability of the PWP and TTad practice context for a client and inform treatment planning – including any tailoring of care that may be indicated.

In Theme 2 the aim is to build PWP knowledge, skills and confidence to navigate the key barriers to engaging with Step 2 treatments for depression and anxiety that clients with personality difficulties may encounter. In particular, ‘common factor’ skills in how to maintain the LI frame; manage the therapeutic alliance; and build PWP interpersonal effectiveness. The workshop also considers how PWPs might deliver brief emotion regulation psychoeducation to support client engagement with LI depression and anxiety treatments. The focus is on finding some flexibility and personalisation in how the core LI-CBT treatment protocols for depression and anxiety are delivered, which supports fidelity to the model – rather than leading to therapist drift in the face of complexity. The possible strengths unique to LI working that may support clients with complex problems to engage in therapy are also discussed.

Theme 3, which supports PWPs to recognise the importance of and build their own self care when working with complex clients, is threaded throughout the workshop.

Participants

PWPs from TALKWORKS NHS Talking Therapies service were invited to attend the 1-day CPD workshop during their usual working hours by their service. As of 30 March 2022, there were 139 PWPs employed within the service; 103 (74%) were qualified (including senior and lead PWPs); and 36 (26%) were trainees/apprentices; 117 (84%) were female, 56 (40%) were aged between 21 and 30, 44 (32%) between 31 and 40; 22 (16%) between 41 and 50; 11 (8%) between 51 and 60; and six (4%) between 61 and 70. Of the 103 qualified PWPs, one (1%) had <1 year of qualified experience, 68 (66%) had between 1 and 5 years of experience; 26 (25%) had between 5 and 10 years of experience; seven (7%) had between 10 and 15 years of experience; and one (1%) had >15 years of experience. Ethnicity data were available for 133 PWPs; 118 (89%) identified as White British; seven (5%) identified as Other White backgrounds; three (2%) as Asian or Mixed Asian backgrounds; one (1%) as Black or Black British; one (1%) as Chinese and three (2%) as Other Ethnic Group.

This opportunity was offered as part of routine service delivery to support PWPs in their ongoing professional registration requirements and professional development. Advertising and management of workshop attendance was therefore managed by the clinical service. PWPs were informed about the workshop by email, which described the title, aims and an overview of the workshop content.

Initially, the service invited the full workforce to register for one of five workshop dates, on a first-come, first-served basis, with each workshop capped at 45 attendees, allowing sufficient places across the five workshops for the full workforce to attend if they wished.

The workshop cap was decided by the facilitator team, as in their experience of delivering CPD workshops, there is an impact on the interactivity and time for breakout groups to feedback after activities. The ideal cohort size is between 20 and 30 PWPs to enable sufficient opportunity to engage in discussion, whilst being enough attendees to have a diversity of views and experience levels.

Following feedback from the first workshop, particularly from senior PWPs as well as facilitator reflections, places on the subsequent four workshops were restricted to qualified PWPs. Trainee PWPs were able to join the subsequent workshops only as the exception with agreement from their supervisor that it was appropriate for their stage of development. One trainee PWP who attended the first workshop reattended the fifth workshop as a qualified PWP; another attended twice but did not provide feedback and therefore the context of this is unknown.

As the feedback survey did not collect data on PWP qualification status, and trainees were allowed to attend the initial workshop, and with exception the subsequent workshops, all workforce-level data are presented across the full workforce (inclusive of both trainee and qualified PWPs).

Workshops took place between May 2022 and March 2023. Overall, 104 attended the workshop (74% of the full workforce), and 74 provided feedback (71% of attendees; 53% of workforce).

As the feedback audited in this paper was collected primarily to inform refinement of the workshop throughout the pilot, and was not collected in the context of research, no demographic data were collected linked to the PWPs who provided feedback.

Two PWPs attended more than one workshop, resulting in 106 recorded attendances, and 75 feedback responses over five workshops: 25 attendees in Workshop 1 (W1); 17 in W2; 28 in W3; 19 in W4; and 17 in W5. Feedback was provided by 19 (76%) in W1; 13 (77%) in W2; 13 (46%) in W3; 16 (84%) in W4; and 14 (82%) in W5. Due to data errors and duplicate attendance, the feedback from two PWPs was excluded from the quantitative audit (first attendance feedback was included). This resulted in 73 PWP responses included in the quantitative audit.

Measures

In line with other CPD workshops delivered by the clinical trainers to monitor the quality and acceptability of training provision, attending PWPs were asked to complete a brief online feedback survey at the end of the workshop. This feedback survey included a mixture of quantitative ratings questions and open answer qualitative questions:

A bespoke feedback questionnaire (Supplementary materials Section 4) asking the extent to which PWPs agreed that the workshop was theoretically interesting, clinically useful, well presented and they would recommend it to other PWPs on a 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree, with ‘neutral’ as the midpoint.

A bespoke 5-item attitudinal questionnaire (Supplementary materials Section 5) capturing therapist-perceived improvements in confidence following the workshop to work with clients with personality difficulties focusing on: assessing clients with personality difficulties, determining suitability of Step 2 treatment; anticipating and managing difficulties in the therapeutic alliance; making a treatment plan; and making adaptations for emotional and interpersonal difficulties to support engagement. A final question captured the extent to which a PWP felt excited/positive about working with clients with personality difficulties in general. These items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree, with ‘neutral’ as the midpoint. Both scales were adapted from a measure developed for the HIT workshop (Warbrick et al., Reference Warbrick, Dunn, Moran, Campbell, Kessler, Marchant, Farr, Ryan, Parkin, Sharpe, Turner, Sylianou, Sumner and Wood2023).

Open answer written qualitative questions (Supplementary materials Section 6) prompted attendees to describe elements they liked and thought could be improved about the workshop; what the PWP would do differently as a result of the workshop, and an open answer response box for ‘any other comments’.

Analysis

All feedback was anonymised prior to analysis. Statistical analyses used jamovi (The jamovi project, 2021) statistical software (a user interface for R; R Core Team, 2018). Quantitative data analysis involved reporting descriptives and percentages of responses to feedback questions. Qualitative data analysis was supported by NVivo for management of the data (NVivo, 2018). Thematic analysis was informed by the framework method (informed by the framework approach; Gale et al., Reference Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid and Redwood2013), and adopted an integrated deductive and inductive approach to ensure research questions were sufficiently addressed, whilst allowing room to explore participants broader experiences of the workshop.

Following the approach recommended in the framework method, all co-authors familiarised themselves with the data from the first three workshops. The primary analyst familiarised themselves with all the data. The primary analyst open coded the first three workshops, and mind maps were created to visualise the key themes emerging from each workshop. These were discussed separately with each of the co-authors (T.L. and B.D.), to discuss codes and agree, refine and elaborate on emerging themes.

An overall working analytic framework was then developed, which consisted of a hierarchical structure of themes, subthemes and codes to guide the coding of the rest of the data. This was partly informed by the survey/research questions, and behavioural change theory (COM-B; Michie et al., Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011). Qualitative analysis was performed iteratively as the feedback was collected, and informed refinement of subsequent workshop delivery.

Results

Quantitative workshop feedback

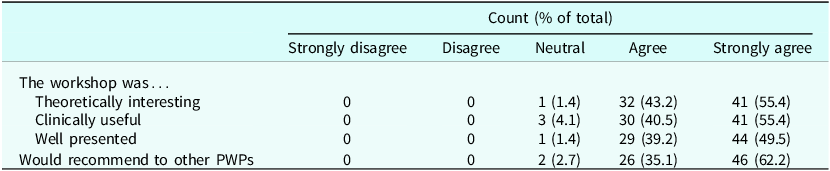

Overall, an overwhelming majority (96–99%) of PWPs responded ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ that the workshop was theoretically interesting, clinically useful, well presented, and that they would recommend it to other PWPs (see Table 1). The remainder of responses were neutral (between one and three PWPs per question; 1.4–4.1%), which were exclusively from Workshops 2 and 3. No PWPs submitted negative responses (‘disagree’ or ‘strongly disagree’) to any of these feedback questions.

Table 1. Count and percentage (%) of total responses to each workshop feedback question

Across the full sample of PWPs, the mean response was >4 (‘agree’); and the median and mode response to each feedback question was 5 (‘strongly agree’; see Table 2). Across individual workshops, the mean, median and mode response to each feedback question was ≥4 (‘agree’).

Table 2. Mean (median, mode) responses to workshop feedback questions across each workshop

Quantitative PWP-perceived confidence and attitudinal data

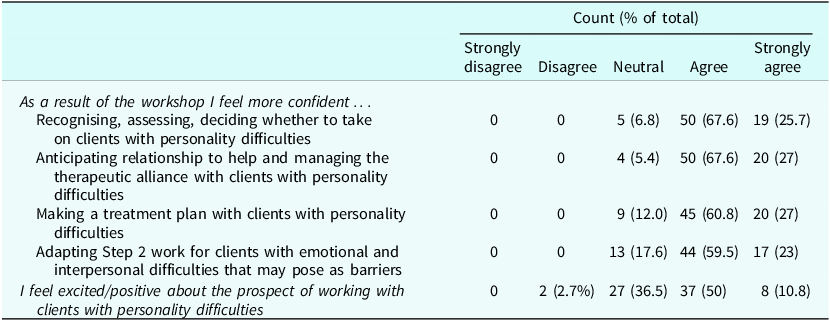

A similar pattern of results emerged when examining PWPs’ perceived improvement in confidence to recognise and assess personality difficulties; anticipate and manage challenges to the alliance; make a treatment plan with clients with personality difficulties; and adapt Step 2 work for emotional and interpersonal difficulties; with a majority of PWPs (82–95%; see Table 3) responding ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ to these attitudinal statements. There were higher rates of ‘neutral’ responses than to feedback questions, although this remained a minority (7–18%), and no PWPs responded ‘disagree’ or ‘strongly disagree’ (see Table 3). Neutral responses were recorded by 15 PWPs, predominantly from Workshops 1–3 (just one PWP in each of Workshops 4 and 5 recorded neutral responses). Overall, three PWPs (4%) endorsed a neutral response for all four of perceived confidence improvement questions.

Table 3. Count and percentage (%) of total responses to perceived confidence and attitudinal questions

Across the full sample, the mean, median and mode response to perceived confidence questions was ≥4 (‘agree’). This was also true across each individual workshop, with the exception of the mean response to confidence in adapting Step 2 practice in Workshop 2 (see Table 4).

Table 4. Mean (median, mode) responses to perceived confidence and attitudinal questions across each workshop

The pattern of responses to the attitudinal question was less strongly positive, where PWPs were asked whether they felt excited/positively about working with clients with personality difficulties, with a smaller majority agreeing or strongly agreeing (61%), 37% responding neutrally and 3% of PWPs disagreeing. Overall, the mean response was <4 (‘agree’), and the median and mode response was 4 (‘agree’). Within individual workshops, the mean response ranged from 3.38 to 3.85 (between ‘neutral’ and ‘agree’); and median and mode responses between 3 (‘neutral’) and 4 (‘agree’; see Table 4).

Overall, quantitative data indicated PWPs experienced the workshop as theoretically interesting, clinically useful, well presented, and that they would recommend it to other PWPs and reported it had improved their confidence in key skills covered which aim to enhance practice with clients with personality difficulties (88–99%; see Tables 1 and 3). A majority of PWPs also reported feeling positive/excited about working with clients with personality difficulties after participating in the workshop (61%), although PWPs were more likely to report feeling neutrally to this question (36%), and a small minority disagreed (3%).

Qualitative feedback

General feedback

A significant proportion of qualitative feedback focused on overall impressions of the workshop (which was overwhelmingly positive) and minor practical suggestions for improvement. These aspects were used to refine further workshops and their facilitation (predominantly relating to formatting/presentation of slides, timing and number of activities and inclusion of trainees as previously described, see Supplementary Materials Sections 2 and 3). However, a key theme that spoke to the acceptability of the training was around ‘relevance to PWP practice’ e.g. ‘[the workshop was] Very PWP focused, so helpful to have someone leading who had been a PWP to help navigate the difficult combination of being theoretically interesting but also relevant to PWP practice’ (PWP10).

In order to understand the extent to which the workshop may have enabled PWPs to enhance their practice, the COM-B model of behavioural change (Michie et al., Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011) was used as a framework to understand emerging themes relating to barriers and enablers of behavioural change. See Fig. 1 for a visual summary of the framework and key themes.

Figure 1. Visual summary of the qualitative data framework (informed by COM-B model of behavioural change (Michie et al., Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011); including key themes and overview of the direction of experiences within the theme.

Capability

PWPs commonly described improved confidence to work with clients with personality difficulties; as well as being more able to understand and recognise these difficulties e.g. ‘[I] feel more confident in understanding and recognising the signs of both PD and difficulty. [And I have] a more thorough understanding, leading to increased confidence in clinical role’ (PWP58). There were more mixed experiences around having developed a dimensional understanding of personality difficulties. One PWP described feeling less clear, e.g. ‘I still don’t fully understand how a personality disorder can be on a continuum’ (PWP99); whereas others described this concept accurately, e.g. ‘personality disorders being on a spectrum that can change over time […] as opposed to thinking of it being a set diagnosis […]’ (PWP12).

Several PWPs also described their understanding of key messages around determining suitability for TTad services, e.g. ‘I feel that as long as the risk are stable enough for IAPT, I would feel more confident delivering a S2 intervention to someone who has personality difficulties’ (PWP24) and ‘it is not that we are suddenly being asked to assess and treat personality disorders but how personality difficulties may present and be considered in step 2’ (PWP27); whereas others seemed less sure on ‘where the line is drawn’ and would have liked clearer ‘service guidelines’, which appeared to be linked to a weaker understanding of the dimensional framework.

Opportunity

PWPs described experiences related to the opportunities within the workshop, as well as the opportunities within their role and future practice. Broadly, PWPs spoke positively about the opportunities for reflection and role-play illustration and practice within the workshop, despite recognising that they could be challenging, e.g. ‘as much as role play can be daunting, it was good to break up the sessions with interactive parts’ (PWP12); although some felt more complex client examples would have been preferable, e.g. ‘[To improve] maybe showcase a bit more around more reluctant patients or more risky patients as in reality we do come across this quite often’ (PWP81).

PWPs also spoke about how they viewed the opportunities within their low-intensity role to work with this client group, e.g. ‘It was just good to talk in a more inclusive way about some of the people we come across and to know we have room for some flexibility – it doesn’t just have to be a case of “personality difficulty? Right, you’re out”’ (PWP82). However, another PWP spoke about the balance between opportunity and constraints of their role ‘I think this has given PWPs more idea about what is possible. Unfortunately it doesn’t change the structure we work within at a service level’ (PWP49).

Motivation

PWPs also described experiences consistent with being more motivated to undertake this work, including being more open-minded, and ‘less judgemental’ towards working with clients with personality difficulties, e.g. ‘I will carefully consider the appropriateness of step 2 work before assuming it won’t be effective’ (PWP68); ‘It has made me more open-minded – coming from working with people with personality disorders in secondary care, I had a bias that it would always be more challenging than it realistically needs to be to work with someone with personality difficulties during LI work’ (PWP8).

PWP behavioural intentions

PWPs also readily volunteered what they planned to do differently in their practice as a result of the workshop, with the most common plans including being more interpersonally effective (or using the interpersonal effectiveness frame); provide clients with emotion regulation tools; and considering past client experiences of therapy as well as the principles of trauma/adversity informed care. PWPs also described planning to adopt a more flexible approach to working with this client group, e.g. ‘Consider some of their difficulties/barriers in mind and how Step 2 could be adapted within our boundaries’ (PWP70).

PWP self-care

A further theme which emerged linked to, but distinct from, motivation was around practitioner self-care. One PWP described the workshop as giving them ‘permission to be human imperfect and make mistakes’ (PWP57); and others planned to strive to be a ‘good enough’ therapist, not a ‘perfect’ one. However, another commented, ‘Placing responsibility on PWPs to work out how to meet the challenges of the difficulties feels overwhelming and is unlikely to be possible sustainably within current targets’ (PWP49), suggesting that they may have interpreted the workshop as an additional ‘ask’ of PWPs; rather than supporting them around work they are already doing.

Discussion

The present study describes the co-design process of a CPD workshop for PWPs aiming to enhance Step 2 practice in the context of personality difficulties; and an audit of feedback from a single-service pilot of the workshop. The overall engagement with the workshop was excellent (87% of combined trainee and qualified workforce; despite not all trainees being eligible to attend) and the response rate to feedback surveys was high (>70%), indicating that the workshop was an acceptable proposal and it was feasible to capture brief feedback of workshops as part of routine CPD practice. The audit of mixed-methods feedback indicates that the workshop was acceptable and viewed as highly relevant, suggesting that the co-design process was successful in developing a workshop tailored to the PWP context from the existing HIT training.

Quantitative feedback indicated PWPs had improved capability (knowledge, skill and confidence) to work with clients with personality difficulties, which was strengthened by qualitative feedback where practitioners described increased confidence, and many demonstrated their understanding of key messages. This is a promising finding given feeling unskilled was a key challenge described by TTad practitioners in previous qualitative research (Lamph et al., Reference Lamph, Baker, Dickinson and Lovell2019); and that higher therapist-perceived competence has been shown to be positively associated with clinical outcomes (e.g. Espeleta et al., Reference Espeleta, Peer, Are and Hanson2022) and lower percieved competence linked to increased burnout (Spännargård et al., Reference Spännargård, Fagernäs and Alfonsson2023).

The qualitative analysis suggested the workshop provided PWPs the opportunity to practise and reflect on key skills, and better understand the opportunities for flexibility within their role, whilst maintaining fidelity to the evidence base and the limits of low-intensity working. In the context of previous qualitative research finding flexible approaches to be more acceptable to clients, and less likely to leave practitioners feeling ‘out of control’, this also suggests the workshop may have had a positive impact (Lamph et al., Reference Lamph, Baker, Dickinson and Lovell2019; Lamph et al., Reference Lamph, Baker, Dickinson and Lovell2021). The themes within the ‘motivation’ aspect of the qualitative analysis also suggested some positive attitudinal changes within the PWPs, who described feeling more open-minded towards these clients, more hopeful about their ability to benefit from Step 2 treatments, and less pressure to be a ‘perfect’ PWP. In contrast, one PWP described it as ‘overwhelming’ for PWPs to be asked to accommodate personality difficulties in their practice. Previous qualitative research found overwhelm was a common feeling when working with this client group, and it is not surprising that some PWPs voiced a similar feeling after the workshop (Lamph et al., Reference Lamph, Baker, Dickinson and Lovell2019). This difference is likely explained by the variation in experience and skills and training requirements and preferences. The behavioural intentions to implement learning and skills from the workshop were also consistent with the teaching and key messages. Overall, these are promising findings suggesting that it was feasible to deliver and gather feedback; the workshop was broadly viewed as acceptable and useful to the PWPs; improved PWP confidence in key skills to enhance PWP practice in the context of personality difficulties and contributed to building the necessary enablers (capability, opportunity, motivation) of behavioural change (Michie et al., Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011) to implement these skills.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations linked to the nature of the pragmatic audit design, including a lack of demographic data or the post-qualification experience range within the sample. There is a higher proportion of PWPs from a white ethnic background in the wider local workforce compared with TTad services nationally; however this is consistent with the regional demographics (Health Education England, 2023; Office for National Statistics, 2021). Further, there was higher than the national average proportion of qualified relative to trainee PWPs (74% in the current workforce; 63% nationally). The results cannot be generalised beyond this particular service context and the PWPs who opted to attend and give feedback. Reasons for PWPs not attending the workshop, or providing feedback are unknown, and it is possible that the group attending and providing feedback represented those for whom the workshop was acceptable and were more likely to engage and benefit from the workshop. The single time-point design limits the inferences that can be made between the workshop and therapist-perceived confidence, although it is a relative strength that PWPs’ perceived improvement in confidence in key skills covered is captured. The qualitative theme of improved confidence implies this resulted from the workshop, and the descriptions of various components of the COM-B behavioural change model also broadly suggests the workshop provided enablers to support PWPs to enhance their practice. However, the lack of a longer-term follow-up to assess subsequent implementation of the learning means it remains an open question whether the behavioural intentions PWPs described led to longer term changes in their practice, or whether these changes led to measurable improvements in client outcomes.

Similarly, although it is promising that the audit found a majority of PWPs expressed positive attitudes towards working with clients with personality difficulties at the end of the workshop, it is a relative limitation that this questionnaire item was not phrased in change terms, and thus no inference can be made as to whether the workshop showed potential to improve attitudes in this respect. The qualitative theme of feeling more open-minded towards this group is promising in this regard, but overall the evaluation was limited by the single time-point design and no measure of baseline attitudes. Critically, this audit does not provide data on how these therapist outcomes might impact on care delivery and client clinical and engagement outcomes.

Conclusions

Despite a number of significant limitations linked to the pragmatic audit design of this pilot, this study provides promising data supporting the acceptability and feasibility of a workshop of this kind, which improved PWP-perceived confidence in key skills to adapt practice in the context of personality difficulties; and that a majority of PWPs felt positively about working with this group afterwards. Given the small investment of resources, and that workshop attendance will contribute to continued registration CPD requirements, these are arguably outcomes ‘worth having’ from a service perspective; irrespective of whether the behavioural intentions described in the feedback are ultimately realised.

Future directions

This pilot supports the feasibility and acceptability of gathering feedback as part of routine CPD provision, and providers and services should aim to embed this to monitor the quality and acceptability of training.

Future evaluations should adopt a formal research perspective, aiming to evaluate the workshop’s effectiveness to improve PWP attitude, knowledge, skill and confidence to work with clients with personality difficulties in a diverse set of TTad service contexts (including variation in client demographics and service policy and guidance). To maximise engagement, protected time within the workshop day should be offered for PWPs to engage with research surveys. Ideally these evaluations should be across multiple service settings and include a longer-term follow-up to evaluate whether post-workshop behavioural intentions to implement new learning are actualised. Given similar educational interventions have improved workforce wellbeing/burnout (e.g. Finamore et al., Reference Finamore, Rocca, Parker and Blazdell2020) and burnout is known to be prevalent within the PWP workforce (Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017), longer-term follow-ups should also aim to evaluate whether the workshop has potential to improve PWP wellbeing and burnout.

To explore whether the workshop has any impacts on client clinical outcomes, future research should embed a clinical outcomes evaluation. It is likely that impacts on service-level clinical outcomes will be modest, and may be challenging to capture within a complex system (for example due to noise from high workforce turnover and seasonal changes in recovery rates). Equally, pragmatic interventions such as this CPD workshop may not translate into improved service-level outcomes, even if they have a positive impact on the client experience. Research should therefore also aim to clarify what a meaningful and measurable ‘return for investment’ would be from the perspectives of key stakeholders including: clients, clinicians, service (lead)s and commissioners. This would be beneficial for psychological professions more broadly, as CPD workshops are a core requirement of continued professional registration, and significant time and resources are committed to CPD provision to these workforces – with little understanding of the possible benefits (or harms) of the diverse and largely unregulated offers from external providers.

Finally, the link between personality difficulties and outcomes within the Step 2 context needs to be more thoroughly understood. There is strong evidence within Step 3 care, or when collapsing across the TTad service that personality difficulties are linked to poorer outcomes (Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Wingrove and Moran2015; Mars et al., Reference Mars, Gibson, Dunn, Gordon, Heron, Kessler, Wiles and Moran2021). However, this link has not been examined within the Step 2 context independently, nor have potential differences between low-intensity formats been explored. An Australian primary care study of computerised CBT for depression and anxiety found no impact of personality difficulties on outcomes in either pure-self help or guided self-help formats (Mahoney et al., Reference Mahoney, Haskelberg, Mason, Millard and Newby2021). If replicated within the Step 2 TTad setting, this may suggest people with personality difficulties are less disadvantaged in treatment formats with a different interpersonal format compared with more traditional face-to-face or telephone working. Understanding the effectiveness of different Step 2 treatment formats in the context of personality difficulties could feed into future training workshops and/or guidance to improve treatment allocation and enhance outcomes for these clients.

Key practice points

-

(1) This skills workshop focused on subtly adapting PWP practice to support more effective working with complex clients at Step 2 seemed an acceptable approach to this clinical issue, and was viewed as highly relevant to PWPs’ routine practice.

-

(2) Skills workshops such as the one evaluated here have potential to improve PWP knowledge, skill and confidence to enhance low-intensity practice for complex clients and those with concurrent personality difficulties.

-

(3) This audit indicates it is feasible and acceptable to gather feedback as part of routine practice for CPD workshops.

-

(4) COM-B offers a useful framework to understand barriers and enablers to implementing new learning from CPD in PWP practice.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X24000266

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, L.W., upon reasonable request and approval from TALKWORKS NHS Devon Talking Therapies service. The data are not publicly available as they relates to NHS staff and HRA/NHS REC approval will be required prior to any data sharing for the purposes of research.

Acknowledgements

Grateful acknowledgements are made to TALKWORKS NHS Devon Talking Therapies service and AccEPT Clinic for support of this project. The authors would like to thank Eve Bampton-Wilton for her contributions to developing the training workshop; the TALKWORKS PWP team for providing the feedback reported within the manuscript; and Katie Marchant for providing a PPI perspective on the training workshop.

Author contributions

Laura Warbrick: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Funding acquisition (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Resources (lead), Software (lead), Validation (lead), Visualization (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Timothy Lavelle: Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Resources (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Barnaby Dunn: Conceptualization (supporting), Funding acquisition (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (lead), Writing – review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research in the UK (NIHR) Three Schools Mental Health fellowship awarded to the corresponding author (L.W.; grant reference number: MHF011) and the Exeter Collaboration for Academic Primary care (APEx), Department of the NIHR School for Primary Care Research (SPCR; L.W.; grant internal reference: 2134690). The views expressed in this protocol are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health or Social Care.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

Authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Procedures were carried out in compliance with local policy; and the audit was approved by both the clinical service (TALKWORKS) and university research clinic (AccEPT Clinic). This routine audit of feedback is not considered research, and the findings are not intended to be generalised and therefore did not require additional ethical approval from a committee. The outcomes of the audit were intended to refine the workshop content and delivery, with the aim of reaching a position where formal evaluation of its effectiveness, acceptability and feasibility could be conducted.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.