Disaster-related events have the potential to result in physical and emotional sequelae in non-physician healthcare workers (HCWs) who care for victims worldwide. The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated the acute and long-term effects of a pandemic on mental health issues, particularly among HCWs.Reference Hoffmann, Schulze and Löffler 1 -Reference Cohen, Cardoso and Kerr 3 Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, concerns have emerged about mental health, isolation, burnout, and stigma that HCWs experienced.Reference Nabavian, Rahmani and Seyed Nematollah Roshan 4 , Reference Ménard, Soucie and Ralph 5 Further, 1 in 5 HCWs experienced a mental health disorder since the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States in 2020, including depression, anxiety, stress, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).Reference Fond, Fernandes and Lucas 6 -Reference Salari, Khazaie and Hosseinian-Far 11 As more information about dangerous conditions related to the response to disasters and outbreaks becomes available, there is room to respond to the need for high-quality treatment and interventions to address and prevent the risks in the mental health decline of HCWs.Reference Lee, Ling and Boyd 8 , Reference Sovold, Naslund and Kousoulis 12 , Reference Chersich, Gray and Fairlie 13

Non-physician HCWs were evaluated at different time periods during the COVID-19 pandemic to understand challenges related to coping with mental health disorders in their respective clinical occupations.Reference Jain, Das and Talwar 14 , Reference Nieuwenhuijsen, de Boer and Verbeek 15 The adaptations and demands on HCWs during highly transmissible infectious disease events such as the COVID-19 pandemic are often accompanied by elevated levels of external stressors, including positioning the well-being of patients ahead of their own, maintaining compliance with professional and ethical policies set by their workplaces, and preserving their personal safety.Reference Dobalian, Balut and Der-Martirosian 16 The pandemic painted a clear picture of how profoundly non-physician HCWs felt that they lacked satisfactory levels of confidence to succeed in managing humanitarian needs in diverse types of disasters while putting themselves at risk.Reference Dobalian, Balut and Der-Martirosian 16 As a result, HCWs left their respective careers after experiencing poor mental health, and some have been unable to return.Reference Ofei and Paarima 17 , Reference Algunmeeyn, El-Dahiyat and Altakhineh 18

Non-physician HCWs have a long history of tailoring their professional experiences while adapting to threats to public health from natural disasters and catastrophic events.Reference Fletcher, Reddin and Tait 19 As professionals trained in life-preserving measures, non-physician HCWs deliver care in various settings while supporting and directing the flow of clinical encounters for multidisciplinary patients and teams.Reference Fletcher, Reddin and Tait 19 Expectations and accompanying complexities of clinical, administrative, and personal responsibilities of non-physician HCWs can contribute to poor health and test their resilience, even if they are not directly interacting with patients who are experiencing symptoms related to ongoing outbreaks.Reference Li, Scherer and Felix 9 Clinical centers can take steps to encourage and support the use of virtual groups to allow open communication and promote safe spaces for non-physician HCWs to discuss and share coping strategies.Reference Valizadeh, Zamanzadeh and Namdar Areshtanab 20 -Reference Viswanathan, Myers and Fanous 23 However, these resources and recommendations are often overlooked or sidelined due to the constant awareness and responsiveness HCWs are presumed to have and often decide to manage as a part of their profession.Reference Kabasinguzi, Ali and Ochepo 21 , Reference Pollock, Campbell and Cheyne 24 Further, these resources and recommendations may not be implemented as well among HCWs who interact only with patients who do not have symptoms reflective of the ongoing outbreaks.

The purpose of this study is to examine the national impact of workplace factors during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on mental health, sleep, and fatigue experienced by non-physician HCWs, including those who may not interact directly with symptomatic patients. We aim to understand whether workplace policies, safety protocols, and exposure to COVID-19 pandemic-related events were associated with mental health during the pandemic.

Methods

This study consisted of an online convenience sample of non-physician HCWs, including nurses, medical assistants, and physician assistants. Participants were recruited to participate in the online REDCap survey through social media, emails sent from professional societies such as the American Association of Medical Assistants, and online boards for the targeted groups. The survey was open between February 1, 2021, and July 15, 2021. Study methods were approved by the University of Texas Medical Branch Institutional Review Board.

Interested participants who did not give their consent to participate were removed from the survey. The survey included a total of 83 questions, including multiple-choice and free-text questions. Participants were not compensated for participation, but $1 in credit was donated to the American Red Cross for each completed survey. The survey included items on workplace factors, including whether HCWs work with symptomatic patients as part of their job, access to personal protective equipment, specialized training, and information while on the job. The survey also included questions about discrimination and whether they had given or received the COVID-19 vaccine. These were all questions that were asked during the COVID-19 pandemic and had not been adequately addressed as factors potentially associated with stress and mental health conditions at the time the survey was developed (see supplemental information for survey).

Stress Measure

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) is a 10-item measure developed to assess individual stress levels. This commonly used measure indicates how often participants felt symptoms indicative of stress during the past month. Responses ranged from 0 = “Never” to 4 = “Very often,” with 4 items reverse scored as indicated in the survey’s scoring instructions, for a total possible score ranging between 0 and 40. Individual scores were added to determine total scores for each participant. The combined score was dichotomized using a standard cutoff of 13 to determine level of stress (scores >13 indicated moderate to high stress). Internal consistency reliability of this measure was found to be high with a Chronbach’s alpha of 0.82 for this study.

Depression Measure

The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CESD-10) measures depressive symptoms during the past week using 10 items. Possible responses range from 0 = “Rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day)” to 3 = “Most or all of the time (5-7 days).” Items were added for a combined score that was then dichotomized into scores of < 10, considered at “average” risk, and ≥10, considered “at risk” for depression. Internal consistency reliability of this measure was found to be high (Chronbach’s alpha = 0.88).

Fatigue Measure

Fatigue was measured using the 10-item Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS), a measure with good reliability and validity for assessing fatigueReference Michielsen, De Vries and Van Heck 25 in different populations through a Likert rating scale ranging from “never” (1) to “always” (5). The 10 items (Chronbach’s alpha = 0.91) were combined after reverse scoring 2 items consistent with instructions, with the total possible combined scores ranging between 10 and 50. The final score was dichotomized using the 50% cutoff to indicate low fatigue (score < 23) and high fatigue (score≥23).

COVID-19 Vaccination

Participants were asked if they had received at least one dose of an FDA-approved vaccine for the SARS-CoV-2 virus with possible responses of “yes” or “no.” Participants who responded negatively were asked what would encourage them to get vaccinated, and they could type free text responses to that question. The next question asked, “If you had access to vaccines that have been approved by the FDA to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection, would you administer them to patients?” They had a choice of 5 responses, including “yes,” “no,” “yes, I have administered them already,” “I am not certified to administer vaccines,” and “I am not sure.” For those who responded “no” or “I am not sure,” respondents could provide a typed explanation for their reason.

Sources of Trusted Information

Participants were asked about how much information they needed to keep themselves safe from the SARS-CoV-2 virus at work and during normal daily activities. They were then asked, “What sources of information do you trust to give you more information about the SARS-CoV-2 virus and COVID-19?” Non-mutually exclusive responses included “Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),” “World Health Organization (WHO),” “peer-reviewed scientific literature,” “associated press,” “social media, like Facebook, Instagram, etc.,” “doctors or nurses,” “family,” “magazines,” “health sites on the internet,” “Johns Hopkins,” “the place where I work,” and “other.” Those who responded “other” had the opportunity to describe what other sources of information they trusted in a free-text box.

Work Environment and Training During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Fourteen questions regarding interaction with patients who had been infected, quitting or reducing hours due to the pandemic, adequacy of workplace protocols and training related to the pathogen, need for additional information, discrimination due to working with infected patients, and whether workers had received a dose of the COVID-19 vaccine were included in the survey. Responses were multiple-choice. Items with Likert scales were collapsed into fewer categories to simplify comparisons.

Demographics

Questions about race/ethnicity, age, and relationship status were adopted from census questions. Marital status added the option of “living with partner.” The question “What is your gender?” included the options “male,” “female,” and “non-binary.”

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate analyses were conducted to assess the association of COVID pandemic work environment and training questions with binomial stress, depression risk, and fatigue variables. To assess associations between sleep and focal outcomes, t-tests were conducted to evaluate whether sleep scores were associated with binomial outcomes, including stress, depression risk, and fatigue. Multivariable binomial logistic regression was used to examine the direction and strength of any significant associations (alpha = 0.05) observed in bivariate analyses after controlling for gender. All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

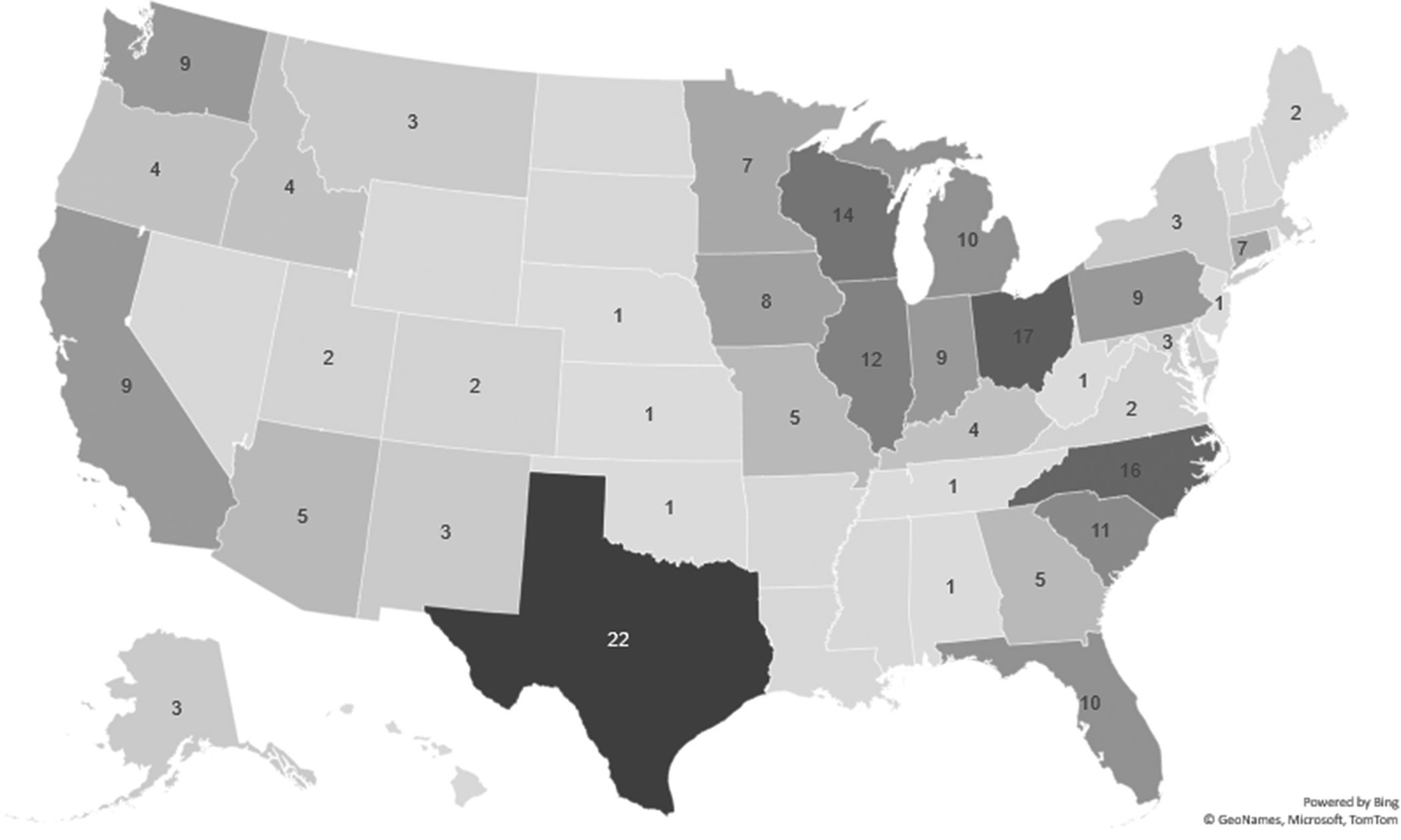

Of 305 total surveys received, 220 surveys included affirmative responses to the consent, were complete, and were completed by a participant who had at least one of the licenses or certifications of interest in this study. Participants lived in 39 of the 50 US states (Figure 1). Most of the respondents were female (94%) and non-Hispanic white (85.9%, Table 1). Respondent age ranged from 19 to 71 years old. Most respondents reported they were medical assistants. The mean perceived stress score was 23.7, with 79.1% reporting a score ≥13, which is considered moderate to high stress. The mean depressive symptom score derived from the CESD-10 was 11.6, with 54.1% reporting a score above 10, indicating they are at higher risk of developing depression than the average population.

Figure 1. Distribution of participants living in the United States included in study.

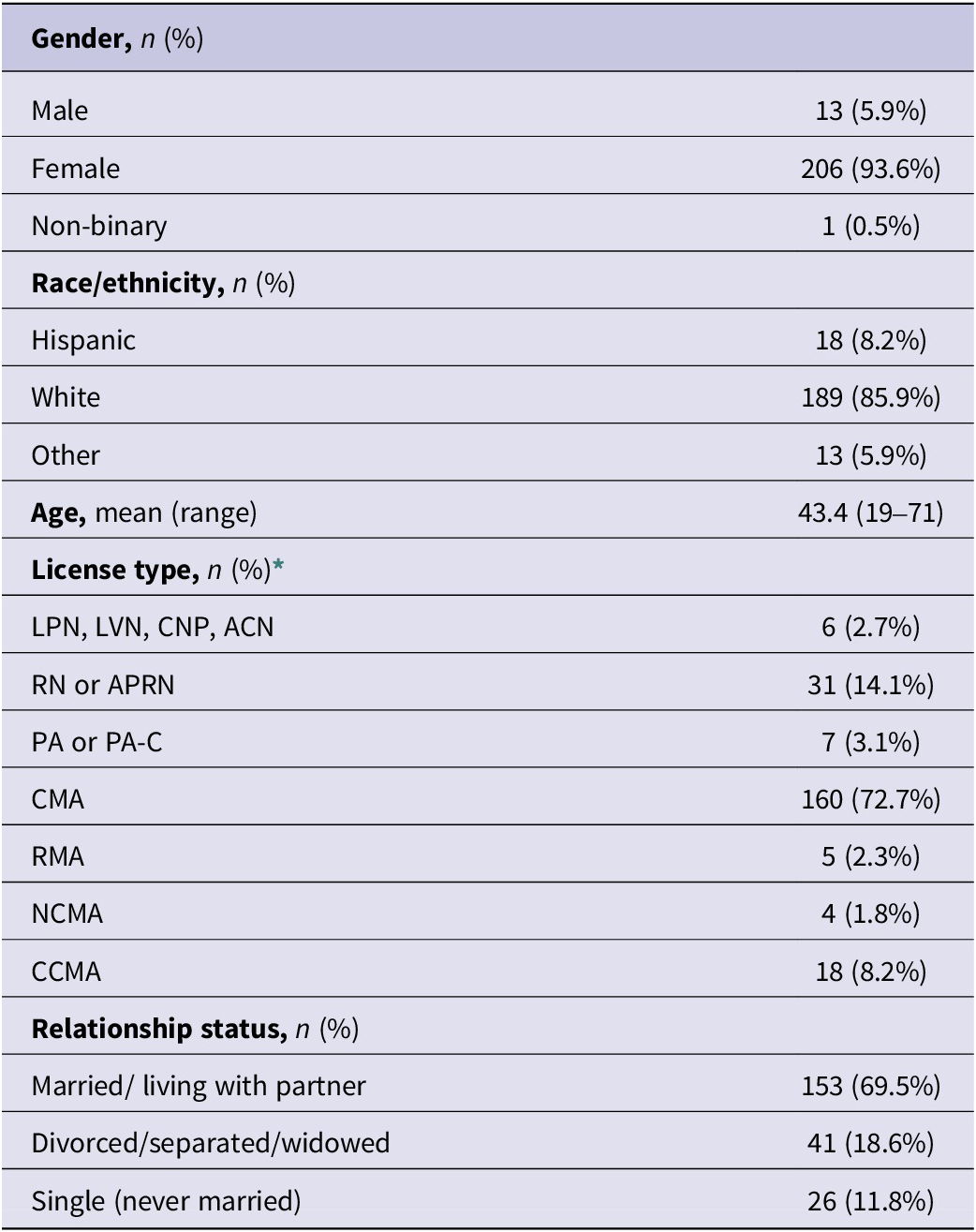

Table 1. Sample characteristics for national survey of non-physician healthcare workers (N=231)

* License type was non-mutually exclusive. Values add up to greater than 100%.

In this sample, 180/220 (81.8%) reported receiving at least one dose of an FDA-approved vaccine. Of those who did not, some things that would encourage them to get a COVID vaccine included the following: if they see other people getting it (n = 1), if it is required by their employer (n = 13), if COVID-19–related hospitalizations increase (n = 2), if COVID-19–related deaths increase (n = 1), and if protection from SARS CoV-2 lasts a long time (n = 3). Some (n = 16) responded they will never get it. A large proportion reported administering the vaccine to patients or being willing to administer the vaccines (205/220, 93.2%), although 8 participants were not certified to administer vaccines. An additional 5 were not sure, and 2 were not willing to administer the vaccines.

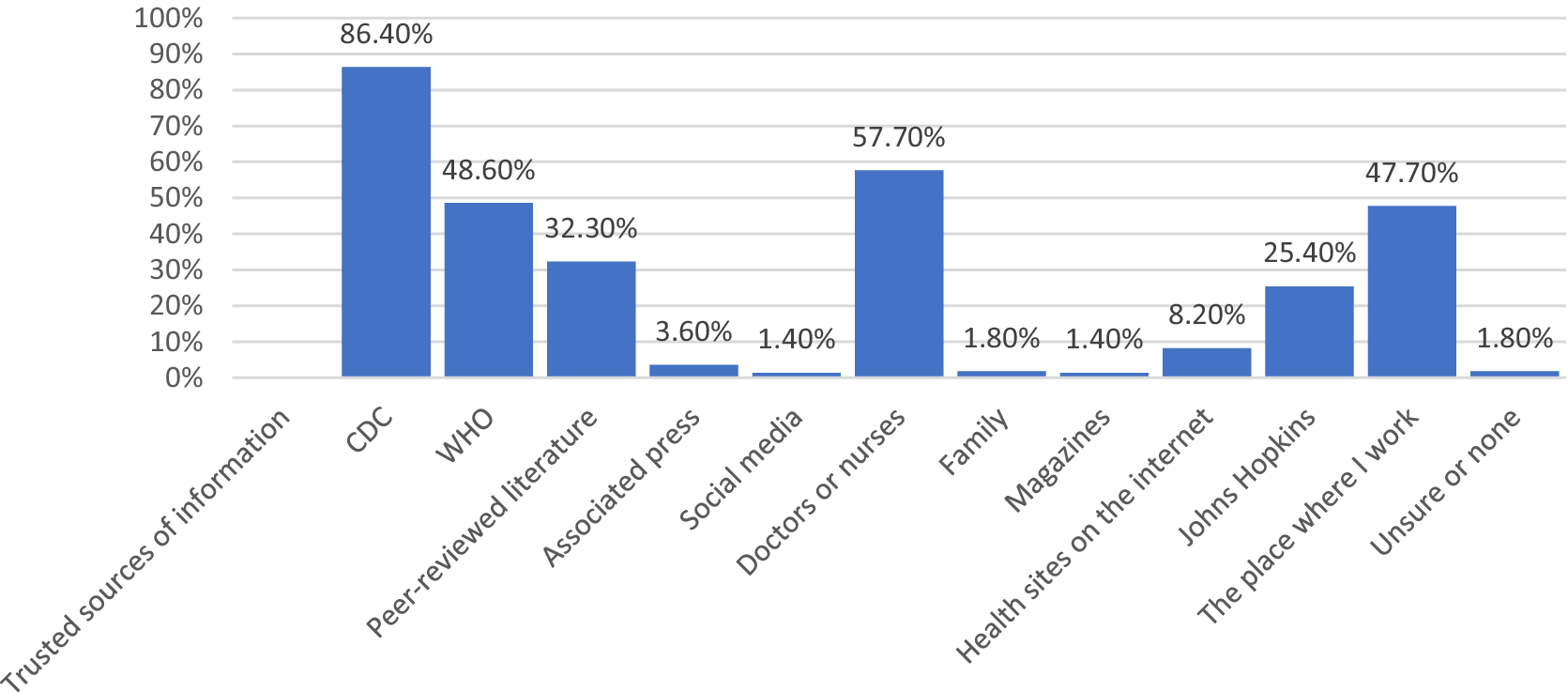

Sources of information about SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 that were used most frequently by non-physician HCWs (Figure 2) included the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 86.4%), the World Health Organization (WHO, 48.6%), peer-reviewed literature (32.3%), doctors or nurses (57.7%), Johns Hopkins (25.4%), and the place where they worked (47.7%). A small proportion of respondents trusted social media, internet health sites, or family to provide information about the virus and COVID-19.

Figure 2. Sources of information trusted by non-physician healthcare workers about the SARS-CoV-2 virus and COVID-19.

Evaluation of associations between workplace practices and perceived stress determined that several workplace-related factors that occurred during the pandemic were associated with moderate to high levels of perceived stress (Table 2). Medical workers who treated or interacted with at least 1 patient who died due to COVID-19 had a higher frequency who reported moderate to high stress (93.3%) compared to those who had no patients who died (59.3%, p < 0.001). Concern with transmitting SARS-CoV-2 to family and friends and suspecting infection with the virus in their own history were also associated with moderate to high stress. A higher proportion of participants who thought about (91.7%) or who had reduced their hours or decided not to take a position because they felt they would be unsafe treating or working with COVID patients reported moderate to high levels of stress (95.6%) compared to those who did not report that (75.1%, p < 0.05). A higher frequency of those who felt they needed more information to keep themselves safe from the SARS-CoV-2 virus (92.9%) reported moderate to high levels of stress compared to those with adequate information (75.8%, p < 0.05). Among those participants who perceived discrimination due to working with patients who may have exposed them to SARS-CoV-2 infection, 90.1% reported moderate to high stress as compared to those who did not (73.8%, p < 0.01). A high proportion of participants who thought their family and friends would be infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the next month reported moderate to high stress (90.7%) compared to those who felt infection was not very or not at all likely (73.1%, p < 0.01). Having protocols, understanding them, and being prepared to follow protocols to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission was not significantly associated with stress levels, nor was the adequacy of training employers provided to prevent transmission. It should be noted that almost all reported having established protocols in place (96.4%).

Table 2. COVID-19 pandemic workplace factors and healthcare workers’ perceived stress (N = 220)

PSS=perceived stress scale-score >13 cutoff considered moderate to high stress. Total column frequencies may not add to 220 for each survey item due to missing values.

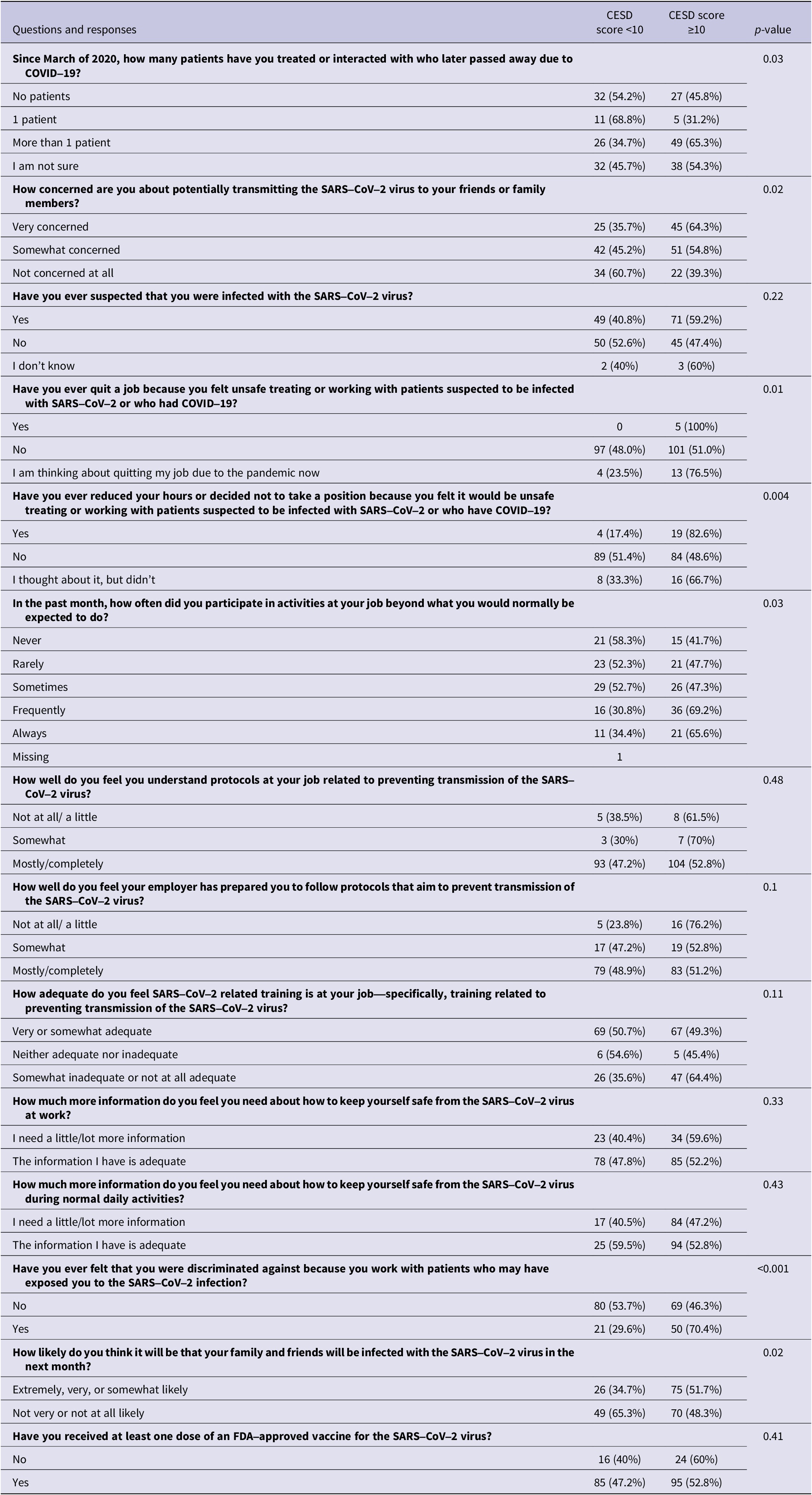

Some workplace factors were also associated with having a higher risk of depression (Table 3). Working with or treating patients who died due to COVID-19 was associated with being at risk of depression (p < 0.05). Being concerned with transmitting SARS-CoV-2 to friends or family was also associated with higher risk of depression (p < 0.05). Reducing hours or not taking a position because medical workers felt they would be unsafe treating or working with COVID-19 patients was associated with higher risk of depression (p < 0.01), as was participating in activities at their job beyond what they would normally be expected to do (p < 0.05). Discrimination due to working with patients who may have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 was associated with having a higher risk of depression (p < 0.001), as was thinking it was likely that their family and friends would be infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the next month (p < 0.05).

Table 3. COVID-19 pandemic workplace factors and healthcare workers’ depression risk (CESD-10) (N=220)

CESD-10=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale ≥10 cutoff considered having elevated risk for depression. Total frequencies may not add to 220 for each survey item due to missing values.

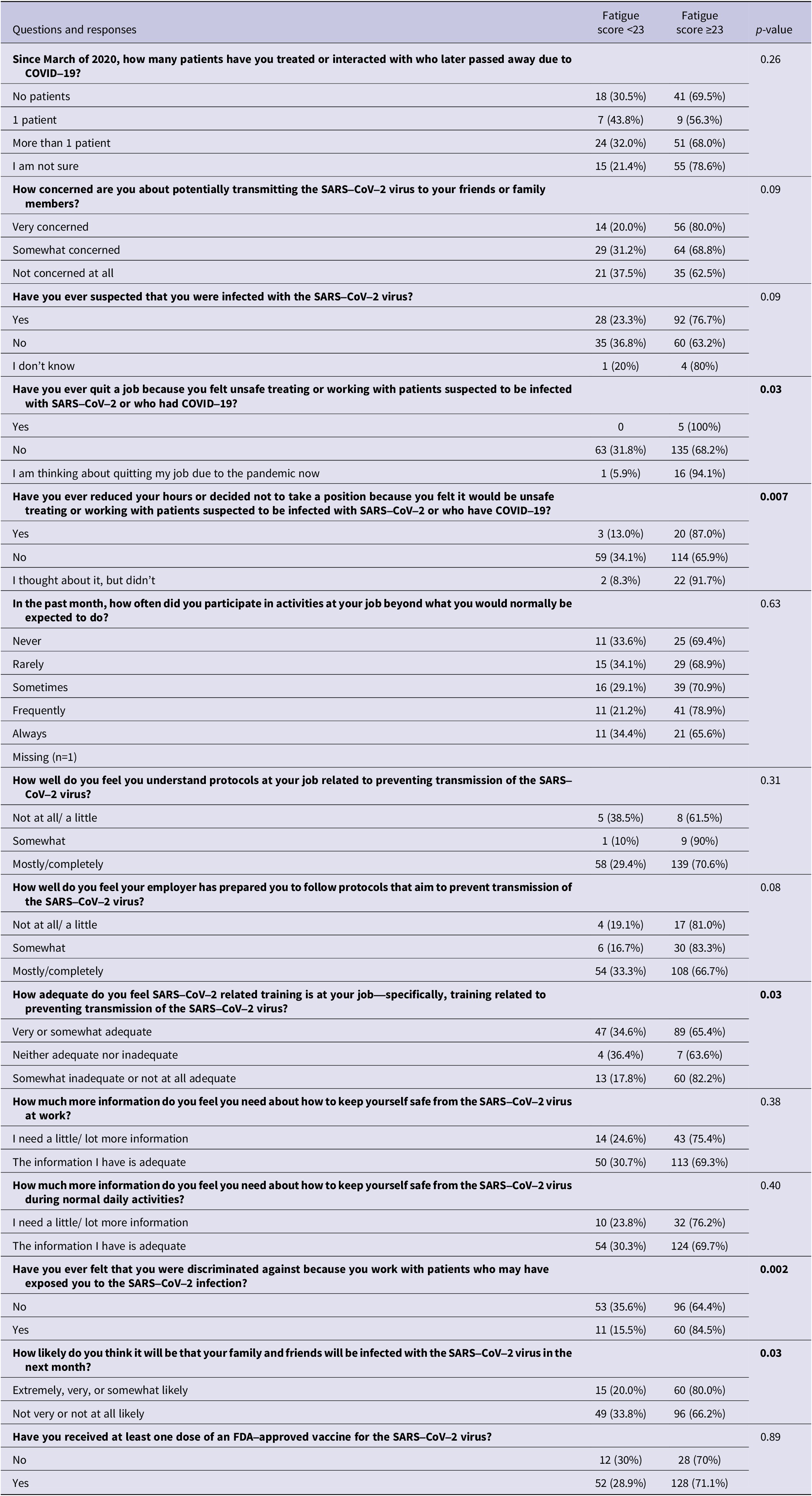

Fatigue was also associated with some workplace factors (Table 4). Of the 5 participants who reported quitting their jobs because they felt unsafe treating or working with patients suspected to be infected with SARS-CoV-2, 100% had symptoms consistent with high fatigue, and 92% of those who thought about quitting their job for the same reason also reported high levels of fatigue. Among HCWs who reduced their hours or decided not to take a position due to feeling unsafe caring for patients with COVID-19, 87% had high fatigue levels. Among those who thought about reducing hours, 92% reported high fatigue levels. Fatigue was also associated with adequacy of pandemic-related training at their job, discrimination due to working with patients who may have exposed them to SARS-CoV-2 infection, and thinking their family or friends will be infected with the virus in the next month.

Table 4. COVID-19 pandemic workplace factors and healthcare workers’ fatigue (Fatigue Assessment Scale) (N = 220)

Fatigue Assessment Scale ≥23 cutoff considered positive for fatigue. Total frequencies may not add to 220 for each survey item due to missing values.

Multivariable analyses that examined associations between workplace factors and stress, depression, and fatigue revealed that after adjusting for participant gender, having treated 1 or more patient who died due to COVID-10 was strongly and positively associated with stress and more modestly associated with higher risk of depression compared to those who reported no patient deaths (Table 5). Being very concerned about potentially transmitting the SARS-CoV-2 virus to friends or family members was associated with high stress, having a higher risk of depression, and reporting high fatigue. Participants who did not suspect they had been infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus had lower odds of having high stress levels compared to those who did suspect they had been infected. Respondents who reported that they frequently participated in activities at their job beyond what they were normally be expected to do in the past month had higher odds of reporting high stress or being at higher risk of depression compared to those who never were expected to complete activities beyond those normally expected. Adequacy of training related to the pandemic was negatively associated with odds of high fatigue and higher risk of developing depression. Respondents who thought they had not been discriminated against because they work with patients who may have exposed them to the SARS-CoV-2 virus had lower odds of reporting high stress, being at higher risk of depression, or high fatigue compared to those who thought they had been discriminated against. Finally, thinking that family or friends would be infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the next month was associated with more than 3 times the odds of reporting high stress and more than 2 times the odds of being at higher risk of depression or having high fatigue.

Table 5. Multivariable binary logistic regression evaluating the association between workplace factors and stress, depression, and fatigue (N=220)

Discussion

Overall stress score samples were high compared to a global sample collected during the COVID-19 pandemic (19.1 PSS score globally compared to 23.7 in this study).Reference Adamson, Phillips and Seenivasan 26 The proportion of non-physician HCWs in this study who were at high risk of depression was 54% compared to 31.7% of US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown.Reference Rosenberg, Luetke and Hensel 27 These differences suggest that there were additional factors affecting depressive symptoms than what were experienced by the general public during the pandemic. This study indicates modifying some workplace factors could have an effect on the levels of stress, depression, and fatigue among HCWs. A systematic review identified several factors identified as important factors in mental health outcomes and sleep disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic, an effect that worsened over time.Reference Georgousopoulou, Pervanidou and Perdikaris 28 These studies demonstrated that female nurses caring for symptomatic patients were particularly vulnerable.Reference Georgousopoulou, Pervanidou and Perdikaris 28 Factors that were associated with improved outcomes included having adequate information, job satisfaction, training, and cooperation among team members.Reference Georgousopoulou, Pervanidou and Perdikaris 28 Ensuring that HCWs have adequate support and counseling during a time when they are exposed to uncertainty in the face of increasing mortality events is important to prevent burnout and reduce poor mental health outcomes, but more may be required to engage HCWs, including those who may not be viewed as being at higher risk of exposure. Some interventions in previous research have been identified that may improve mental health among HCWs.

One intervention, for example, includes development of psychologic resilience through assignment of another person as a “battle buddy,” or a coworker who understands the challenges posed by the pandemic or another disaster and can provide support in addition to psychological care through mental health consultants.Reference Albott, Wozniak and McGlinch29 A survey study that identified employees who had patients die under their care in Israel found that HCWs who cared for COVID-19 patients experienced higher levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms compared to those who did not work with COVID-19 patients during the pandemic.Reference Mosheva, Gross and Hertz-Palmor 30 These findings highlight the importance of having active plans in place to address additional stress posed by mass casualty events. Specific recommendations, such as monitoring stress levels through surveillance and reallocating workloads in ways that can reduce stress, have been recommended by the American Medical Association. 31 Support includes not only adequate insurance for mental healthcare but also organizing the workforce to allow workers to feel they may take time to care for mental health and provide easily accessible resources for self-care.Reference Moore, Wigington and Green 32 Although several studies have been done regarding mental health and resilience of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic, more work needs to be done to ensure study planning is done and interventions are ready to implement and test during future healthcare crises.Reference Pollock, Campbell and Cheyne 24

Mental health among HCWs across all specialties, not just those directly interacting with patients with symptoms, should be of concern to healthcare facilities where they work because these individuals often provide supporting roles that are critical to supporting and maintaining an organization’s healthcare function. One randomized controlled trial designed to reduce stress across several different types of HCWs was successful at decreasing work-related rumination and post-traumatic stress symptoms but did not reduce perceived stress.Reference Mengin, Nourry and Severac 33 Some undefined factors, therefore, may play a role in stress, including different workplace conditions that may exist during a pandemic. Some workplace conditions have been shown to be associated with psychological health of emergency HCWs, including concerns about catching SARS-CoV-2 at work and a lack of personal protective equipment.Reference Corradi-Dell’Acqua, Horisberger and Caillet-Bois 34 However, these studies were done in Europe where there were differences in the level of misinformation and vaccine acceptance as compared to the United States.

Nurses have reported practicing outside their normal duties, a finding confirmed among more than half of the non-physician HCWs in our study.Reference Ness, Saylor and Di Fusco 35 Medical workers should not be expected to participate in activities beyond what they would normally be expected to. However, during a pandemic, it may be impossible to ensure this does not happen. Therefore, there should be a strong plan in place to ensure these duties are allocated on a limited basis and that safety is not compromised. If roles are permanently expanded, or long-term changes are made based on experiences during the pandemic or other disasters, then roles could be officially expanded and titles with increased pay and appropriate education and training be given as well.Reference Jackson and Nowell 36

Medical workers reported discrimination in housing and other services as well as from family and friends if they were perceived to be potentially infectious to contacts.Reference Spruijt, Cronin and Udeorji 37 Although there is little to be done about this in the workplace, discussions surrounding these topics and offering resources to medical workers to assist them with housing or social support could help to improve mental health outcomes. Pandemics are often accompanied by an uptick in incidences of public harassment, attacks causing bodily harm, and even deaths.Reference Ramzi, Fatah and Dalvandi 38 Person-to-person interaction and shortage of appropriate personal protective equipment available to shield physician and non-physician HCWs increased public hostility toward the healthcare system.Reference Chersich, Gray and Fairlie 13 , Reference Xiao, Zhang and Kong 39 HCWs exposed to COVID-19 were unable to return to their respective homes and families, causing an exceptional level of physical and emotional isolation and exacerbation of existing mental health conditions.Reference Xiao, Zhang and Kong 39 , Reference Nestor, O’Tuathaigh and O’Brien 40 Further, the rapid turnaround time for the development of the COVID-19 vaccine and its prioritization for specific members of society, including frontline HCWs, added a layer of condemnation, vaccine hesitancy, and bodily threats to the workers and the public.Reference Huang, Ganti and Graham 41 The potential for these problems needs to be taken into account for disaster planning, including response by HCWs, with previous suggestions for reducing the effects of discrimination including placing priority in fostering resilience among HCWs using theory-driven interventions and supporting well-being.Reference Labrague, De Los Santos and Fronda 42

In addition to improving workplace factors to improve mental health, the COVID-19 pandemic illustrated the importance of distribution of accurate information in a timely manner. Understanding the sources of information trusted by HCWs provides additional avenues of ensuring information is provided in a way that is easily accessed by HCWs. For example, the CDC was trusted by many non-physician HCWs in our study. Ensuring that there are messages that are tailored to this group and disseminated through physicians and their clinics as well as through the CDC would potentially reduce misinformation that was prevalent during the COVID-19 pandemic and encourage adherence to public health guidelines.Reference Wang, Li and van Antwerpen 43 Given that personal protective equipment provides COVID-19 protection when used properly,Reference Soleman, Lyu and Okada 44 providing HCWs with information about its proper use as well as its efficacy may reassure HCWs that they are safe in their roles. Further, distribution of information could be done through local and national organizations that support the licensure and work of medical assistants and other types of HCWs as well as through regular empathetic communication by healthcare leaders.Reference Bhat, Bhat and Saba 45

Limitations

Although this study provides some information about associations between workplace factors and mental health, much work needs to be done to better understand how to support medical workers adequately when exposed to unusual and disaster conditions, such as a pandemic or other disaster event that may include mass casualties. This study cannot determine causality, as mental health factors may influence how HCWs perceive their workplace practices. Although this was a national study, it may not be completely generalizable to all HCWs. However, it does offer some insight into associations between mental health and workplace factors among non-physician HCWs.

Conclusion

Ultimately, it is important that employers in the field of health care be aware that workplace factors that result from disaster events may have an impact on the mental health of HCWs. This is important given the high rates of burnout and turnover among HCWs, particularly among those with health conditions, higher numbers of COVID-19–related concerns, and who identified as non-white in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic.Reference Mercado, Wachter and Schuster 46 The importance of planning by healthcare facilities for future incidents should include consideration of additional stressors that may place HCWs at risk both within their positions as well as within the community where they work. Improved and preliminary planning may mitigate issues before they arise and reduce confusion and make mental health interventions more accessible and effective if implemented at an early stage. Finally, streamlining communication processes to ensure employees have valid information from their workplace, sources they trust, and their healthcare clinicians should be a priority to reduce the spread of misinformation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2024.131.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the efforts of the AAMA in assisting us to recruit participants for this study.

Author contribution

WLM and JMH originated and conducted the study, analyzed the data, and drafted the initial manuscript draft. TOK drafted the initial manuscript. SJG assisted in data collection efforts. All authors participated in interpreting the results, provided critical feedback to the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript draft for submission.

Funding statement

This project is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $1,921,225 with 1.5 percentage financed with nongovernmental sources. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government.

Competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.