1. Girls’ educational disadvantage in Nepal

In our community, girls do not need this [English-medium education].

Interview with male teacherNepal is classified as a low-middle income country (World Bank, Reference World Bank2023), and like other such countries, it is under international pressure to attain gender equality targets in order to receive international aid. However, Nepal is also permeated by widespread perceptions that girls are subordinate to boys, which influences girls’ access to education, information, health and the labour market (Upadhaya & Sah, Reference Upadhaya, Sah and Douglas2019). Women face restrictions in terms of their basic ability to ‘independently venture outside the household, maintain the privacy of their bank accounts, use mobile phones, or become employed’ (Karki & Mix, Reference Karki and Mix2022: 413). Illiteracy disproportionately affects females, with 58.95% of illiterates being women and girls (UNESCO, 2021). Notwithstanding this, recent years have seen some progress in enhancing gender equality in Nepal, and females currently enjoy higher enrolment rates than males across secondary education (UNESCO, 2023). This article, however, provides evidence that the recent trend to offer English-medium education risks setting back progress made by creating a gender-differentiated system that could yield different outcomes for boys and girls and potentially restrict girls’ future trajectories post school and contribute to broader gender inequality in society.

Like many other low and middle income countries, Nepal, a highly multilingual, multi-ethnic and socio-economically stratified nation, where 124 languages are spoken as a mother tongue (Government of Nepal, 2023), has seen a recent surge in English-medium education. This has particularly been the case since 2015 when a radical decentralization of the education system took place, devolving power over educational policy to local municipalities. As a result, increasing numbers of schools have begun to offer English-medium education instead of or in addition to Nepali-medium education (Sah & Karki, Reference Sah and Karki2023). Despite never being a British colony, English enjoys high symbolic status and prestige (Sah & Li Reference Sah and Li2018). Additionally, although Nepali is the official language, it is the first language only of approximately 45% of the population (Government of Nepal, 2023). Thus English potentially serves as an additional lingua franca alongside Nepali and other languages such as Hindi, although English language proficiency levels are variable and generally low (EF EPI, Reference EF EPI.2023). The push for English medium education takes place in spite of UNESCO's longstanding recommendation, originally conceived in 1953, to provide mother tongue-based education, at least at primary level (UNESCO, 1953). This policy is backed up by considerable evidence that has shown that students in multilingual contexts tend to learn best in their home language, at least at the stage of developing literacy (Clegg & Simpson, Reference Clegg and Simpson2016; Skutnabb–Kangas, Reference Skutnabb–Kangas2000; Trudell, Reference Trudell2016).

However, in highly multilingual countries, mother tongue-based education may not always be practically implementable given teacher shortages, lack of teaching and learning resources in indigenous languages, and the sheer number of indigenous languages brought to the classroom by students (Erling, Adinolfi & Hultgren, Reference Erling, Adinolfi and Hultgren2017). In Nepal, where more than 124 languages are spoken, classroom practices tend to be much more multilingual than official policy. Moreover, the notion of the ‘mother tongue’ has been problematized, and other concepts, such as ‘linguistic citizenship’ and ‘translanguaging’ have been developed to advocate for a less top-down and a priori approach to language policy that recognizes a wider range of communicative resources drawn on by language users in educational domains (e.g., García & Wei, Reference García and Wei2014; Williams, Deumert & Milani, Reference Williams, Deumert and Milani2022). Translanguaging – the use of teachers’ and learners’ entire linguistic repertoire to facilitate communication – regularly takes place in Nepali classrooms, despite this rarely being endorsed at policy level (Phyak et al., Reference Phyak, Sah, Ghimire and Lama2022; Sah & Li, Reference Sah and Li2022).

This article explores the role of medium of education – as advocated at official policy level – on educational participation and gender equality (see also Milligan & Adamson, Reference Milligan and Adamson2022). Specifically, it asks the question of whether one gender (girls or boys) is overrepresented in the English-medium stream compared to Nepali-medium stream and, if so, why that might be the case.

2. The research

The data for this article are part of a wider research project, English-Medium Education in Low and Middle Income Contexts: Enabler or Barrier to Gender Equality?, funded by the British Council. The project draws on in-depth fieldwork in Nepal and Nigeria as well as a wider cross-country study. In Nepal, the country in focus in this article, data was collected from Shree Durga Vawani Secondary SchoolFootnote 2 in Birgunj, a cosmopolitan city, located 135 km south of the capital Kathmandu. Shree Durga Vawani is a government, mixed-sex, dual-medium school where students are enrolled in either an English- or a Nepali-medium stream. The dataset from Nepal consists of student questionnaires (N=103), classroom observations (N = 12) and interviews (N = 19) with students, parents, teachers, principals and policy makers. In this article, we draw on the interview data. Students interviewed were 14–16 years old, attending Grades 9 and 10 in the Nepali system, or Level 3 in the International Standard Classification of Education (UNESCO, Reference UNESCO.nd.).

The interview transcripts underwent rigorous thematic analysis. The focus was on latent thematic analysis, looking beyond the surface meanings of what participants said to the underlying ideas, assumptions and conceptualisations that may have shaped or informed the semantic content of the data. In accordance with Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2021), each thematic analysis had six core phases: 1. Familiarisation; 2. Coding; 3. Constructing themes; 4. Reviewing themes; 5. Defining themes; 6. Writing up.

In the first stage – familiarisation – the interview transcripts were reviewed for familiarity and errors, and initial notes were taken on any potential points of significance. This was essential in laying the groundwork for the second stage – coding – where the common themes within the study were set out by a process of labelling. Using a colour coding system, common linked statements were highlighted in order to codify them and start dividing them into recurring themes. This round took place twice to ensure rigour and accuracy. Once all significant statements were codified, the third stage – constructing themes – began. This entailed combining labelled codes into broader umbrella themes that covered a wide range of recurring statements and opinions, which led four core themes:

1. The importance of education for gender equality;

2. Attitudes towards medium of education and gender;

3. Obstacles to both accessing and implementing English/Nepali-medium education;

4. Support needed to improve access and implementation of English/Nepali-medium.

In the fourth stage – reviewing themes – all previously identified themes and sub-themes were reviewed in order to reflect on whether they best categorised the findings. This reflection led to some statements moving into different themes that fit better than their first assigned category, while others were removed altogether as they lacked significant presence elsewhere. Next, in the fifth stage – defining themes – the themes were reviewed for a final time and, once satisfied, a theme name was assigned that was succinct, yet clear, relevant and explanatory. Finally, in the sixth stage – writing up – the results of the thematic analysis were reported, with significant findings supported by statements from the written transcripts. In presenting the findings below, representative interview excerpts have been chosen to illustrate the key themes.

3. Enrolment rates in Shree Durga Vawani Secondary School

Before taking a look at the interviews, it's useful to first take a look at gender and enrolment rates in each of the two streams in this dual-medium (English and Nepali) school. Figure 1 shows student enrolment rates in Grades 9 and 10 in Shree Durga Vawani Secondary School. It shows that where boys are fairly evenly distributed across the two streams, girls are not. More than twice as many boys as girls are enrolled in the English-medium compared to the Nepali-medium stream: 75 boys (69%) compared to 33 girls (31%). Conversely, more girls than boys are enrolled in the Nepali-medium stream, but at 72 (53%) versus 65 (47%), the difference is not as stark.

Figure 1. Enrolment in Grades 9 and 10 Shree Durga Vawani Secondary School by language stream and gender

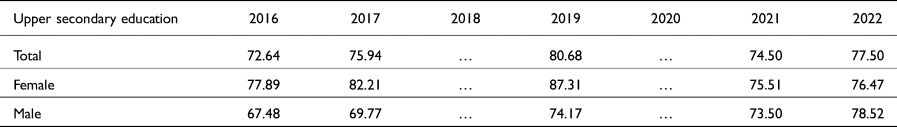

Comparing enrolments in our dual-medium Shree Durga Vawani Secondary School with national enrolment rates in Nepal as a whole (see Table 1), it becomes clear that the English-medium stream in Shree Durga Vawani Secondary School is out of sync with the national trend of an overall higher proportion of female enrolments at upper secondary level.Footnote 1 As can be seen from Table 1, with the exception of 2022, females have higher enrolment rates than males across upper secondary education in Nepal. While the national pattern reflects the pattern for the Nepali-medium stream in Shree Durga Vawani Secondary School, it contrasts markedly with the much greater enrolment of males in the English-Medium stream. It appears then that English-medium education acts as a gender differentiator, separating out boys from girls.

Table 1. National net enrolment in upper secondary education in Nepal (Source: UNESCO 2023) (per cent)

To make sense of these findings, it should be noted that where the English-medium stream charges high tuition fees, the Nepali-medium stream has minimal fees, with the implication that sending their children to an English-medium school represents a considerable investment for parents. Sah & Karki's (Reference Sah and Karki2023) observation that English-medium education is a form of ‘elite appropriation’ here manifests itself in parents apparently being willing to invest more in their sons’ education than in that of their daughters, evidenced in a proportionately higher enrolment of boys than girls in the English-medium stream. This finding confirms other studies about differential parental investment in education. Khanal (Reference Khanal2018), for instance, drawing on longitudinal data from three Nepal Living Standards Surveys, finds that parents display bias in spending on their children's education, with greater expenditure on boys than girls in both rural and urban areas in Nepal. In Khanal's study, this manifests itself in a higher enrolment rate of boys than girls in fee-paying private schools, which in turn is likely to give boys an advantage and potentially enhance their career choices and life opportunities. In the next section, we consider two reasons why parents may be less prepared to invest in their daughters’ English-medium education: gendered societal aspirations and the Nepalese dowry system.

4. Medium of education and gendered aspirations

Interview data suggests that parents’ differential investment in the education of their sons and daughters may be down to the different roles envisaged for girls and boys in society and, relatedly, the extent to which those roles require English. For the vast majority of participants, the advantage of Nepali-medium education is the access that it can provide to employment in the public sector and government jobs, particularly for girls.

In future, many girls want to fight in public service commission examinations, and they will need Nepali for that purpose.

Interview with female policy makerSome teachers feel that English-medium education can be more of a hindrance than a help for girls because many of them will not move abroad. They see EMI as a passing trend, pointing to government jobs requiring Nepali rather than English and that the focus of girls’ education particularly should be on Nepali-medium education:

In our community, girls do not need this [English-medium education]. I have seen the benefit of English nowhere. I haven't seen anywhere in our own surrounding.

Interview with male teacherOn the other hand, there is a widespread perception that the English-medium stream is associated with greater prestige, higher status and an overall greater return on investment. It is associated with careers and further studies in medicine, banking, engineering, business and teaching:

The role that English has played is significant. Whatever one wants to be, engineer or doctor, they need English.

Interview with mother of child in the English-medium streamI want to study MBBS in a foreign university. They speak in English, so it helps me to understand.

Interview with male student in English-medium streamIt is clear that the English-medium stream is associated with greater prestige and for those who can afford it, it is perceived to offer better life and career opportunities. In interviews, some students express frustration at attending the Nepali-medium stream because of their families’ low socioeconomic status. This leads to an overwhelming feeling that they are ‘settling’ for second best and that Nepali has less value:

I would have gone [to an EMI school] if my family financial condition was good.

Interview with female student in Nepali-medium streamNotwithstanding the overrepresentation of boys in the English-medium stream, many participants emphasize the importance of education in general, particularly for girls. There is a general consensus that education is essential for promoting gender equality and providing girls with independence. Both Hindu and Muslim parents and teachers are in agreement that there should be no differentiation between girls and boys when it comes to access to education:

What it is a son or a daughter? They are my children, right! They both are the same. I will give them both an equal education.

Interview with father of student in English-medium streamEducation is also seen as a tool for female independence, providing girls with access to better jobs, greater financial security and opportunities to leave their local communities and move abroad:

They don't have to always remain under men [ . . . ] if girls become self-dependent, they don't have to beg for money.

Interview with female teacher in Nepali-medium streamHowever, despite the insistence of some on girls’ education, many families also highlight the discrimination or stigmatization they face by their local community for wanting to provide their daughters with an education. The quote suggests that it can take some bravery on the part of parents to insist on their daughters’ education:

We get [mental] torture from the society that I'm educating my daughters.

Interview with father of daughter in English-medium streamIt may be that while ensuring their daughters education is just about tolerable in the eyes of some, sending them to an English-medium stream may be considered a step too far and so some parents may choose the Nepali-medium stream for their daughters so as not to stick their head above the parapet.

In sum, interviews with parents, students, teachers and policy makers suggest that the choice between an English- and Nepali-medium steam is linked with educational and professional aspirations which are intrinsically gendered. Although there is insistence by some participants that girls’ education is equally important as that of boys, parents on the whole appear less prepared to invest in the higher-fee English-medium stream for their daughters’ as their onward professional and educational trajectory may not need it and because they may face social sanctions as a result. Given that English-medium education can provide access to a wider range of employment opportunities, often associated with greater influence, status and pay, the choice not to send girls to English-medium secondary education may potentially limit their opportunities and keep them at bay in certain societal roles for which they are deemed suitable because of their gender. On the other hand, it might also be argued that those following the Nepali-medium stream may experience fewer of the challenges that have been shown to be associated with learning in a language other than one's home language. This said, however, it should also be borne in mind that the alternative – Nepali – is not necessarily the home language for all students either.

5. Medium of education and Nepal's dowry system

Another reason why parents may be less prepared to invest in English-medium education for their daughters is Nepal's dowry system. Although illegal, the dowry system requires a payment, such as property or money, to be paid by a bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage.

According to Nepali custom, the further a girl advances in education, the greater her dowry must be. The dowry system means that many parents marry their daughters off at a young age to avoid a higher dowry price. Many parents therefore perceive girls’ education as a bad investment, since daughters move out to live at their husbands’ houses (Upadhaya & Sah, Reference Upadhaya, Sah and Douglas2019). As a female teacher explains:

Dowry is a huge problem. Its effects are dangerous. There is a perception that the more they are educated, the more educated and richer boy they must find. [ . . . ] The more the boy is educated, the more demand they make. So, the reason behind not educating daughters is also this one.

Interview with female teacher in Nepali-medium streamIt may be that the higher cost for the English-medium stream may be seen as not worth paying for girls as they will leave the family and get married.

Where previous research has pointed to Nepal's high rate of child marriage – one of the highest in Asia – as a cause for early school dropouts (Sekine & Hodgkin, Reference Sekine and Hodgkin2017; UNICEF/UNFPA, Reference UNICEF/UNFPA.2017), the research presented here paints a more nuanced picture, pointing to the role of medium of education as a key factor. In other words, it does not appear to be the case that the dowry system and early marriage causes girls to drop out, at least not in Grades 9 and 10 at Shree Durga Vawani Secondary School. This is reflected in Figure 1 which shows that girls in Grade 9–10 actually slightly outnumber boys, at 72 versus 65, in the Nepali-medium stream, which also reflects the national pattern of a slightly greater female enrolment at secondary level. Instead, it seems that different societal aspirations for boys and girls – including the dowry system – combine to make parents less inclined to invest in their daughter's education, which in the case of our dual-medium school means that they are sent to the Nepali-medium stream. This manifests itself in girls being vastly outnumbered by boys (on a ratio of 75 to 33) in the fee-paying English-medium stream. It seems, then, that English-medium education creates and exacerbates gender divides, which might have been less visible in single-medium education.

In addition to potentially reinforcing societal and occupational gender segregation, there is evidence that those students who follow the English-medium stream, most of which are boys, receive a better education, although this is debatable as there may be additional challenges associated with learning in English (Clegg & Simpson, Reference Clegg and Simpson2016; Skutnabb–Kangas, Reference Skutnabb–Kangas2000; Trudell, Reference Trudell2016). Having said this, although students in both the English- and the Nepali-medium stream report challenges that impact adversely on the teaching and learning, the challenges are reportedly greater in the Nepali-medium stream, possibly attributable to fewer resources being allocated to and less prestige being associated with this stream. Thus, while students in both streams report issues such as poor pedagogy, crowded classrooms, absent teachers, lack of equipment, poor facilities, and a lack of fans in temperatures that on hot days can soar to above 40 degrees, the questionnaire excerpts below suggest that teacher absenteeism is particularly acute in the Nepali-medium stream.

Most of the teachers in Nepali mostly remain absent and are not regular in classes. This is the biggest problem in Nepali medium classes.

Interview with female student in Nepali-medium streamThe main problem of Nepali medium classroom is that most of the teachers do not take classes. They mostly remain absent in the classroom.

Interview with female student in Nepali-medium streamMost of our classes are leisure. Teachers do not come to class and they do whatever they like.

Interview with female student in Nepali-medium streamThe reasons for Nepali-medium teachers’ higher absenteeism warrant further research but may have to do with them typically holding permanent contracts (unlike English-medium teachers who tend to be fixed term and part time), and thus perhaps not always being as assiduous in their attendance. However, unlike what is typically the case for English-medium teachers, Nepali-medium teachers are civil servants and hold a teacher qualification. In Shree Durga Vawani Secondary School, the teachers on the English-medium stream, of which – perhaps tellingly from the point of view of gender equity – only one is female, are employed on a part-time basis as they often teach in multiple schools. Despite often being in a hurry to rush between schools, they were less often absent than the teachers on the Nepali-medium stream. On the whole, the generally poorer conditions in the Nepali-medium stream may potentially compound existing disadvantages for the students following this stream and further widen the gap between them and the students enrolled on the English-medium stream, on which males are overrepresented.

Above, we have focused on broad differences between boys and girls as if they were homogenous groups. However, it should be borne in mind that gender intersects with myriads other socio-demographic factors including religion, ethnicity and socio-economic background. Thus, lack of parental investment in education is likely to affect some girls more than others, with particularly adverse impacts having been noted on certain Hindu castes and Muslims and Madheshi ethnic groups that are already marginalized or at risk of exclusion (Upadhaya & Sah, Reference Upadhaya, Sah and Douglas2019). Interview data suggest, for instance, that the problem of early marriage, the dowry system and educational dropout is particularly prevalent amongst Muslims and the Madheshi Dalit community (people belonging to the lowest stratum of the caste system) and is tied up with poverty, prestige and honour, thus further disadvantaging those already disadvantaged (see full research report, Hultgren et al., Reference Hultgren, Wingrove, Wolfenden, Greenfield, O’Hagan, Upadhaya, Lombardozzi, Sah, Adamu, Tsiga, Aishat and Veitch2024).

6. Conclusion

With gender equality and quality of education being two of the Sustainable Development Goals, this article has provided evidence that the recent trend to introduce English-medium education may jeopardize the attainment of these policy aims and risk setting back any progress made. The research reported on educational enrolment and the gendered nature of medium of education in a secondary school in Nepal, highlighting how gendered societal aspirations affected the investment parents are prepared to make in their daughters’ education. Medium of education mediates these decisions with a greater number of boys being enrolled in the more costly English-medium stream. Specifically, we argued that the recent trend to offer English-medium education risks creating a two-tiered, gender-differentiated system that could potentially yield different outcomes for boys and girls and restrict or constrain girls’ future trajectories post school. Thus, medium of education mediates and potentially perpetuates broader gender inequalities in society. Of course, being enrolled and on the school register does not necessarily equate with learning, and so future research will need to look closely at classroom practices to understand how learning and teaching takes place in English versus Nepali-medium streams. Indeed, the role played by English as a medium of education for advancing or hindering teaching and learning continues to be a point of debate in the literature. What seems clear from this research, however, is that policymakers, teachers, parents and students seem united in regarding the more costly English-medium education as an opportunity to improve and expand professional, educational and personal opportunities, and that this choice is, explicitly or implicitly, gendered. Unfortunately, there is also evidence that English-medium education appears to benefit boys and others who are already advantaged while it may serve to further disadvantage girls, particularly those from already marginalized communities.

Funding

Developed with support from the British Council.

ANNA KRISTINA HULTGREN is Professor of Sociolinguistics and Applied Linguistics and UKRI Future Leaders Fellow at The Open University in the United Kingdom. She holds a DPhil in Sociolinguistics (Oxford, 2009), an MA in English and French Language (Copenhagen, 1999) and a Certificate in Public Policy Analysis (London School of Economics and Political Science, 2021). Kristina is Principal Investigator of ELEMENTAL and of EMEGEN, a British Council-funded project exploring the link between gender equality and English as a Medium of Education in low and middle-income countries. Email: [email protected]

ANNA KRISTINA HULTGREN is Professor of Sociolinguistics and Applied Linguistics and UKRI Future Leaders Fellow at The Open University in the United Kingdom. She holds a DPhil in Sociolinguistics (Oxford, 2009), an MA in English and French Language (Copenhagen, 1999) and a Certificate in Public Policy Analysis (London School of Economics and Political Science, 2021). Kristina is Principal Investigator of ELEMENTAL and of EMEGEN, a British Council-funded project exploring the link between gender equality and English as a Medium of Education in low and middle-income countries. Email: [email protected]

ANU UPADHAYA is a PhD Candidate in the Languages, Cultures, and Literacies program at Simon Fraser University, Canada. Anu's research interests lie at the nexus of language & gender, reflecting her commitment to exploring and understanding the complexities of these interconnected fields. Her doctoral research delves into the intersectionality of language, gender, patriarchy, and the emotional well-being of South Asian women immigrants in Canada. Email: [email protected]

ANU UPADHAYA is a PhD Candidate in the Languages, Cultures, and Literacies program at Simon Fraser University, Canada. Anu's research interests lie at the nexus of language & gender, reflecting her commitment to exploring and understanding the complexities of these interconnected fields. Her doctoral research delves into the intersectionality of language, gender, patriarchy, and the emotional well-being of South Asian women immigrants in Canada. Email: [email protected]

LAUREN ALEX O'HAGAN is a Research Fellow in the School of Languages and Applied Linguistics at the Open University and an Affiliated Researcher in the Department of Media and Communication Studies at Örebro University. She specialises in performances of social class and power mediation in the late 19th and early 20th century through visual and material artefacts, using a methodology that blends social semiotic analysis with archival research. She has published extensively on the sociocultural forms and functions of book inscriptions, food advertisements, postcards, and writing implements. Email: [email protected]

LAUREN ALEX O'HAGAN is a Research Fellow in the School of Languages and Applied Linguistics at the Open University and an Affiliated Researcher in the Department of Media and Communication Studies at Örebro University. She specialises in performances of social class and power mediation in the late 19th and early 20th century through visual and material artefacts, using a methodology that blends social semiotic analysis with archival research. She has published extensively on the sociocultural forms and functions of book inscriptions, food advertisements, postcards, and writing implements. Email: [email protected]

PETER WINGROVE is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at The Open University, working on the quantitative component of the UKRI funded ELEMENTAL project on the causes of English-medium instruction in European higher education. Prior to this position, Peter worked as an EAP instructor in China, Korea, and Japan; and wrote his PhD in Applied Linguistics at the University of Hong Kong, specialising in corpus linguistics and EAP. Email: [email protected]

PETER WINGROVE is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at The Open University, working on the quantitative component of the UKRI funded ELEMENTAL project on the causes of English-medium instruction in European higher education. Prior to this position, Peter worked as an EAP instructor in China, Korea, and Japan; and wrote his PhD in Applied Linguistics at the University of Hong Kong, specialising in corpus linguistics and EAP. Email: [email protected]

AMINA ADAMU is Professor of Phonetics, Phonology and Varieties of English and is a Fellow at the Nigeria Centre for Reading Research and Development in Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria. Amina holds an MA (2000) and a PhD (2009) in English language (Bayero University) and a Postgraduate diploma in Education. Email: [email protected]

AMINA ADAMU is Professor of Phonetics, Phonology and Varieties of English and is a Fellow at the Nigeria Centre for Reading Research and Development in Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria. Amina holds an MA (2000) and a PhD (2009) in English language (Bayero University) and a Postgraduate diploma in Education. Email: [email protected]

MARI GREENFIELD is a Research Associate in Health, Wellbeing and Social Care at The Open University. She holds a PhD in Health from the University of Hull and worked on the project “English-Medium Education in Low and Middle Income Contexts: Enabler or Barrier to Gender Equality?” Email: [email protected]

MARI GREENFIELD is a Research Associate in Health, Wellbeing and Social Care at The Open University. She holds a PhD in Health from the University of Hull and worked on the project “English-Medium Education in Low and Middle Income Contexts: Enabler or Barrier to Gender Equality?” Email: [email protected]

LORENA LOMBARDOZZI is Senior Lecturer in Economics at The Open University in the United Kingdom. She holds a PhD in Economics (SOAS, 2018), an MSc in Political Economy of Development (SOAS, 2013) and an MSc in Development Economics (La Sapienza, 2008). Lorena is Co-Investigator of “English-Medium Education in Low and Middle Income Contexts: Enabler or Barrier to Gender Equality?”, a British Council-funded project exploring the link between gender equality and English as a Medium of Education in low and middle-income countries. Email: [email protected]

LORENA LOMBARDOZZI is Senior Lecturer in Economics at The Open University in the United Kingdom. She holds a PhD in Economics (SOAS, 2018), an MSc in Political Economy of Development (SOAS, 2013) and an MSc in Development Economics (La Sapienza, 2008). Lorena is Co-Investigator of “English-Medium Education in Low and Middle Income Contexts: Enabler or Barrier to Gender Equality?”, a British Council-funded project exploring the link between gender equality and English as a Medium of Education in low and middle-income countries. Email: [email protected]

PRAMOD K. SAH is an Assistant Professor of English Language Education at The Education University of Hong Kong. His primary research areas include English-medium instruction, language ideologies, critical translanguaging, affect and emotion, anti-racism and anti-colonialism in language education, and multilingual and multimodal literacies. His research has appeared in many international journals and edited volumes. His latest co-edited volumes are titled Policies, Politics, and Ideologies of English-Medium Instruction in Asian Universities: Unsettling Critical Edges (Routledge) and English-Medium Instruction Pedagogies in Multilingual Universities in Asia (Routledge). He is also an Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Education, Language, and Ideology. Email: [email protected]

PRAMOD K. SAH is an Assistant Professor of English Language Education at The Education University of Hong Kong. His primary research areas include English-medium instruction, language ideologies, critical translanguaging, affect and emotion, anti-racism and anti-colonialism in language education, and multilingual and multimodal literacies. His research has appeared in many international journals and edited volumes. His latest co-edited volumes are titled Policies, Politics, and Ideologies of English-Medium Instruction in Asian Universities: Unsettling Critical Edges (Routledge) and English-Medium Instruction Pedagogies in Multilingual Universities in Asia (Routledge). He is also an Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Education, Language, and Ideology. Email: [email protected]

ISMAILA ABUBAKAR TSIGA is a Professor of English Literature, chair in Life Writing, at the Department of English and Literary Studies, Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria. He holds a PhD in Literature (Essex, 1987), MA English (BUK, 1981), BA English (ABU, 1978) and Advanced Certificate in Education (India, 2001). He was the Director, Education Resource Centre, Federal Capital Territory, Abuja and the pioneer Director, Nigeria Centre for Reading Research and Development, Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria. Email: [email protected]

ISMAILA ABUBAKAR TSIGA is a Professor of English Literature, chair in Life Writing, at the Department of English and Literary Studies, Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria. He holds a PhD in Literature (Essex, 1987), MA English (BUK, 1981), BA English (ABU, 1978) and Advanced Certificate in Education (India, 2001). He was the Director, Education Resource Centre, Federal Capital Territory, Abuja and the pioneer Director, Nigeria Centre for Reading Research and Development, Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria. Email: [email protected]

AISHAT UMAR is an Associate Professor of English Language and Linguistics at the Department of English and Literary Studies, Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria. She holds a PhD in English Language (BUK, 2016) with a specialisation in Stylistics, MA English Literature (2000) BA English (1995) and a Postgraduate Diploma in Education (2005) in the same university. She was a visiting researcher at the School of English, University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom, in 2012. She is currently the Deputy Director (Training and Development) at the Nigeria Centre for Reading Research and Development, Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria. Email: [email protected]

AISHAT UMAR is an Associate Professor of English Language and Linguistics at the Department of English and Literary Studies, Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria. She holds a PhD in English Language (BUK, 2016) with a specialisation in Stylistics, MA English Literature (2000) BA English (1995) and a Postgraduate Diploma in Education (2005) in the same university. She was a visiting researcher at the School of English, University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom, in 2012. She is currently the Deputy Director (Training and Development) at the Nigeria Centre for Reading Research and Development, Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria. Email: [email protected]

FREDA WOLFENDEN is Professor of Education and International Development at the Open University, UK where she has held a number of management positions. During 2019–20 Freda was Education Director for the Girls Education Challenge (GEC), a UK FCDO programme (£500M) supporting the learning of over 1.3M girls in 17 countries. Freda is currently leading research on the Empowering Teachers Initiative, two KIX funded projects concerned with professional development of educators and an exploration of learning teams for the Learning Generation Initiative. Email: [email protected]

FREDA WOLFENDEN is Professor of Education and International Development at the Open University, UK where she has held a number of management positions. During 2019–20 Freda was Education Director for the Girls Education Challenge (GEC), a UK FCDO programme (£500M) supporting the learning of over 1.3M girls in 17 countries. Freda is currently leading research on the Empowering Teachers Initiative, two KIX funded projects concerned with professional development of educators and an exploration of learning teams for the Learning Generation Initiative. Email: [email protected]