In the Earth’s crust, earthquakes happen every day. They happen with no political intention or economic objective. Yet when a major earthquake triggers a social and human disaster, its aftershocks can be deeply political and have important economic consequences. That was true of the Chillán earthquake of 1939, which heavily affected south-central Chile and was a determining factor in some of the most important institutional developments of the period. Footnote 1

The Great Chillán Earthquake happened on the evening of Tuesday, January 24, 1939. That hot summer night, about 150 people had gathered at the Teatro Municipal to see the evening screening of the American film Fit for a King. Footnote 2 Around 11:35 p.m., the ground started to shake, something relatively common in the country. However, this time the movement was unusually abrupt and strong. According to witnesses, it felt like “an epileptic shake, followed by a long death rattle,” consistent with an intraplate event of 7.8 magnitude (Leyton et al. Reference Leyton, Ruiz, Campos and Kausel2009). Footnote 3 In the theater, some ran for the exit while others stayed in their seats, but almost no one survived as the roof and marquee of the building collapsed. In a matter of three minutes, Chillán became little more than “a huge urban tomb.” Footnote 4 From Santiago, Chile’s capital, to Temuco in the southern region, people were trapped in the falling buildings, sometimes in their sleep. This event was arguably the most catastrophic socio-natural disaster in Chilean history. The exact number of casualties remains a mystery, with different sources reporting five thousand to thirty thousand fatalities. The most likely number is around eight thousand casualties, an impressive record for a population of barely 4.3 million.Footnote 5

Disasters were not unknown to Chileans, who had experienced devastating earthquakes before. The Valparaíso quake of 1906 had already shocked the country during the twentieth century, forcing the Chilean state to develop new state capacities in the face of adversity (Martland Reference Martland2007; Valderrama Reference Valderrama2015; Gil Reference Gil2017). By 1939, Chile was significantly more populated, more urbanized, and economically more diverse. As a result, this disaster posed novel reconstruction and recovery challenges for Chilean society in general and the state in particular. In this context, the government of the Popular Front (Frente Popular), led by President Pedro Aguirre Cerda, used the event to advance an agenda of increased state intervention in the economy and society. As part of the reconstruction effort, two new state-led institutions were created: the Reconstruction and Assistantship Corporation (Corporación de Reconstrucción y Auxilio, CRA), and the Production Development Corporation (Corporación de Fomento de la Producción, CORFO). Whereas the former managed reconstruction, CORFO was to lead a program for national production development. Over the years, these institutions would grow to be central in the development of the Chilean state (Meller Reference Meller1996; Lederman Reference Lederman2005; Bravo-Ortega and Eterovic Reference Bravo-Ortega and Eterovic2015). CORFO, in particular, quickly become a cornerstone of the Front’s policies, developing ambitious Immediate Action Plans (Planes de Acción Inmediata) in the areas of mining, electricity, agriculture, commerce, and transport. Thanks to loans from the American Import-Export Bank, CORFO was able to expand these plans and invest in steel, waterpower, and petroleum, among other ventures. Over the years, CORFO has acted as financier, entrepreneur, investor, innovator, and researcher for the Chilean state. Evaluations of its policies are diverse and varied but, overall, it is considered a leading example of a state-led agency to boost industrialization in Latin America (Silvert Reference Silvert1948; Baer Reference Baer1972; Mamalakis Reference Mamalakis1976; Nazer Reference Nazer2016).

Considering the importance of the 1939 earthquake in Chile’s institutional history, there is surprisingly little research about it that does not come from the natural sciences, with the notable exception of architects who have linked it to the development of modern architecture in the country (Aguirre Reference Aguirre2004; Torrent Reference Torrent2016). Some analyses of the period mention the earthquake as the context for the creation of CORFO but do not consider it an important explanatory factor. For most authors, the institutionalization of import substitution industrialization (ISI) policies in Chile was inevitable at that point, and therefore CORFO is presented as a foreseeable outcome (Loveman Reference Loveman1979; Ibáñez Reference Ibáñez1983; Lederman Reference Lederman2005; Henríquez Vásquez Reference Henríquez Vásquez2014; Bravo-Ortega and Eterovic Reference Bravo-Ortega and Eterovic2015; Nazer Reference Nazer2016). In this article, I argue that the earthquake had a greater role in CORFO’s creation than the literature suggests. It is true that by 1939 the need to expand production in the country was shared among different actors (Lederman Reference Lederman2005; Correa et al. Reference Correa, Consuelo Figueroa, Rolle and Vicuña2001). It is also a fact that ISI policies were part of the Front’s plans even before the election campaign (Rosemblatt Reference Rosemblatt2000; Pavilack Reference Pavilack2011). However, at the time of the earthquake, Aguirre Cerda faced a mostly hostile Congress, the opposition of traditional elites, and internal conflict in his coalition, and his recently won election was being questioned by the opposition (Stevenson [1942] 1970; Super Reference Super1975; Pavilack Reference Pavilack2011). It took the earthquake to provide the crucial opportunity to move the plan for state-led industrialization forward. The political fight for CORFO’s creation was intense, both in Congress and outside it. Importantly, it was embedded in the parliamentary bill for reconstruction, and Chilean institutional history would be different otherwise.

The research presented here aims to close this knowledge gap, using primary historical sources to describe the disruptive event and the political juncture that followed, showing that the earthquake was crucial for Chile’s process of industrialization and state building. Also, I aim to provide a broader argument for the study of disasters in social sciences, using the framework of critical junctures.

Catastrophes as critical junctures

Political analysis has sometimes been downplayed in disaster studies, in the belief that disasters should be apolitical and rationally managed (Pelling and Dill Reference Pelling and Dill2010). Footnote 6 However, cases show the opposite is true: catastrophes are deeply political. In Latin America, cases where disasters have become an arena for contestation abound. For example, Walker (Reference Walker2008) shows that the 1746 earthquake-tsunami in colonial Lima affected the stability of the Spanish Crown, as the lower classes were desperate, and the upper class saw a chance to press for independence. McCook (Reference McCook, Buchenau and Lyman2009) studied an earthquake in revolutionary Venezuela that generated so much social anxiety that royalists managed to win power back from creole separatists. And Healey (Reference Healey2011) has presented the case of the 1944 San Juan earthquake, which launched Juan Domingo Perón onto the national political scene in Argentina. As disaster scholars have repeatedly shown, disasters are “all-encompassing occurrences” that sweep every aspect of human life: biological, social, economic, and cultural (Oliver-Smith and Hoffman Reference Oliver-Smith and Hoffman1999). Catastrophes can put institutions and social arrangements to the test, generating different types of social or political “aftershocks” (see also Martland Reference Martland2007; Gawronski and Olson Reference Gawronski and Stuart Olson2013; Zulawski Reference Zulawski2018; Gil and Atria Reference Gil and Atria2021; Piazza and Schneider Reference Piazza and Schneider2021).

It can be useful to frame the analysis of disasters as critical junctures, especially when the focus is to understand their impact on institutions such as the state (Gawronski and Olson Reference Gawronski and Stuart Olson2013). I understand a critical juncture to be a brief phase of institutional fluidity where there is a substantially heightened probability that agents’ choices will affect outcomes (Capoccia and Kelemen Reference Capoccia and Daniel Kelemen2007). In other words, it is a relatively short moment in time during which change is not only possible but actually contemplated. Mahoney (Reference Mahoney2001, 7) uses this approach when he defines critical junctures as a “choice point when a particular option is adopted among two or more alternatives.” This means that the possibilities of what could have happened are not endless; they are determined by the conditions of the critical juncture. Even then, critical junctures are moments of contestation when people “can shape outcomes in a more voluntaristic fashion than normal circumstances would permit” (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2001, 7); decisions are potentially much more momentous, and new institutional trajectories can be set. However, this does not mean that junctures happen completely because of human agency. On the contrary, junctures open because “an event or a series of events, typically exogenous to the institution of interest, lead to a phase of political uncertainty in which different options for radical institutional change are viable” (Capoccia Reference Capoccia, Mahoney and Thelen2015, 6).

The situation in Chile before the earthquake

The 1939 earthquake happened at a moment in Chilean history when emerging middle and working classes were starting to push for social justice and a growing, more active state (Meller Reference Meller1996; Collier and Sater Reference Collier and Sater2004; Pavilack Reference Pavilack2011; Henríquez Vásquez Reference Henríquez Vásquez2014). After decades of extreme laissez-faire economic policies, the 1920s saw the development of social laws that attended to some of the most crucial needs of the people: housing, health, and education (Larrañaga Reference Larrañaga2010; Henríquez Vásquez Reference Henríquez Vásquez2014; Serrano et al. Reference Serrano, Ponce de León, Rengifo and Mayorga2018). Some of these initiatives had their origins even earlier (Yáñez Reference Yáñez2008; Mac-Clure Reference Mac-Clure2012), but by 1930 the situation was still “dramatic” (Serrano et al. Reference Serrano, Ponce de León, Rengifo and Mayorga2018) and the absence of the state was prominent in most sectors (Larrañaga Reference Larrañaga2010).

In the case of industry, the government of Carlos Ibáñez del Campo (1927–1931) had created a Ministry of Development (Ministerio de Fomento) and implemented some “promotion policies” (credit and protectionist tariffs) that were intensified by Arturo Alessandri-Palma (1932–1938). However, by the 1930s, industrialization was still very low, even compared with other Latin American countries (Lederman Reference Lederman2005; Gómez-Galvarriato and Williamson Reference Gómez-Galvarriato and Williamson2009): barely 13 percent of Chilean GDP was produced by industry, with a growth rate of 3.5 percent for the 1908–1930 period (Meller Reference Meller1996, 51). Also, the country had recently gone through two major economic crises due to a decline in the nitrate trade during World War I and the impact of the Great Depression. This had led to a long discussion about the need for economic diversification and expanded industrialization (Correa et al. Reference Correa, Consuelo Figueroa, Rolle and Vicuña2001; Silva Reference Silva2009; Vergara Reference Vergara, Drinot, Knight and Pérez-Sáez2016).

In this context, the Chilean Popular Front—a leftist coalition of the Radical, Democratic, Communist, Socialist, and Radical-Socialist Parties founded in 1937—represented the hopes and dreams of the emerging middle and working classes, which pushed for change (Meller Reference Meller1996; Collier and Sater Reference Collier and Sater2004). The Front’s first aim was to improve the living conditions of the masses by proposing several reforms, such as the expansion of education, protection for rural workers, and a state-led industrialization program (Stevenson [1942] 1970; Super Reference Super1975; Rosemblatt Reference Rosemblatt2000; Barr-Melej Reference Barr-Melej2001; Pavilack Reference Pavilack2011). The second aim was modernization (Rosemblatt Reference Rosemblatt2000; Silva Reference Silva2009), understood as a form of manifest destiny “in which the aims of economic independence, industrial growth and social justice became integrated in a coherent discourse” (Silva Reference Silva2009, 86).

The Popular Front achieved power in 1938 with the election of Pedro Aguirre Cerda as president of Chile (Reference Aguirre Cerda1933, 101). He had been a middle-class schoolteacher before becoming a successful politician. As a key political figure of the Radical Party, he had served as deputy, senator, and minister and was the first Chilean president to be elected distinctively with the votes of middle-class men and blue-collar workers. For Aguirre Cerda, the improvement of living conditions in the country was intimately tied to industrialization; therefore, he thought that this goal should be a primary responsibility of the state. In his work El problema industrial (Reference Aguirre Cerda1933, 101), he claimed that “rulers today are not like old rulers, quiet onlookers of industrial and commercial development, but managers and administrators of a great enterprise, looking for the common good of the national community.” Consequently, his presidential program granted a prominent place for economic planning at the state level. Footnote 7

The overall agreement on the need to augment production, together with the fact that Aguirre Cerda was openly in favor of ISI policies, has led several authors to consider the creation of CORFO as the expected “institutionalization” of these ideas and to assume that there was no disagreement regarding the need for a new corporation (Loveman Reference Loveman1979; Ibáñez Reference Ibáñez1983; Lederman Reference Lederman2005; Henríquez Vásquez Reference Henríquez Vásquez2014; Bravo-Ortega and Eterovic Reference Bravo-Ortega and Eterovic2015; Nazer Reference Nazer2016). However, this is only partially correct. The consensus about the need to expand industrialization was limited by disagreements about the role of the state in this process (Super Reference Super1975; Meller Reference Meller1996; Correa et al. Reference Correa, Consuelo Figueroa, Rolle and Vicuña2001; Collier and Sater Reference Collier and Sater2004). Even the Popular Front lacked a common plan, amid the tension between those who argued for a reformist-capitalist state and the more radical factions who questioned whether industrialization policies actually improved the lives of the poor (Rosemblatt Reference Rosemblatt2000). In addition, Aguirre Cerda’s hard-won election (50.45 percent) was being contested by the opposition, which controlled both chambers of Congress (the Senate and the House of Deputies). Overall, the president was not in a good position to make his ideas prevail when the earthquake happened, a month after his start in office.

The destabilizing event

The 1939 earthquake happened on a Tuesday evening, rattling the city of Chillán, capital of Ñuble Province, and affecting at least eight cities and twelve towns that suffered heavily from the shock. At the capital, casualties were few and destruction was minor, but people were anxious and started to gather outdoors. The government immediately tried to figure out the epicenter of the shock when the telegraph office announced that towns south of Talca were not responding, including the city of Chillán. Footnote 8 President Aguirre Cerda decided to travel to the area immediately, even though electricity was shut down, railroads were useless, and roads were damaged. He managed to arrive in Chillán the next morning, only to confirm that the city was a pile of ruins: buildings were destroyed, streets had almost disappeared, and bodies were being gathered in parks (figure 1; see also additional files). Footnote 9 Authorities immediately organized rescue efforts and the arrival of provisions; the military was put in charge of public order, burying bodies, and providing the post in the main square. Footnote 10 Soon, the central government suppressed local authorities and took control of the four most affected provinces: Ñuble, Concepción, Bio-Bio, and Maule.

Figure 1. President Pedro Aguirre-Cerda in Concepción, days after the earthquake. Colección Archivo Fotográfico, Museo Histórico Nacional.

Ten days after the event, the press claimed that the country was slowly returning to normal; roads were being cleared and trains were running again. Footnote 11 But that was hardly the whole story; 111,984 homes had been lost across the country, with broad destruction of basic services, communications, and infrastructure. Footnote 12 The Ministry of Finance calculated the cost of reconstruction to be 1,719 million pesos, which represented approximately 10 percent of the GDP at the time. Footnote 13 The task ahead was huge.

The moment of contestation

In his seminal work on path dependence in historical sociology, Mahoney (Reference Mahoney2001, 513) states that critical junctures are defined by “the adoption of a particular institutional arrangement from among two or more alternatives.” This means that critical junctures are not just episodes of important or “momentous” decisions but also a time when alternatives are discussed and different outcomes are possible. This is important, for it involves showing that CORFO, like other institutional developments in the reconstruction plan, was not the natural culmination of a growing process of state intervention in the Chilean economy but was one institutional option among others.

To start, the problems posed by the earthquake were interpreted differently by different actors. As Blyth (Reference Blyth2002) has stated, contestation in times of crisis involves discussing not only “what is to be done” but, more importantly, “what went wrong.” Offering a convincing diagnosis is crucial, because it influences the way people and institutions discuss and select possible solutions. For traditional elites, embodied in this case by the opposition, the disaster was seen as a problem of assistance to the victims and restoration of public infrastructure. They expressed their intent to immediately cooperate with the government in such a plan, offering support and arguing for a “methodical and not exaggeratedly expensive” reconstruction plan. Footnote 14 The government, however, had a different interpretation of the tasks ahead. As Aguirre Cerda himself pointed out later, “the earthly cataclysm that we have suffered confirmed to the government the argument formulated before about a lack of foresight to solve fundamental problems of public interest.” Footnote 15 By this, he meant that the earthquake had made it clear that electricity and transportation were lacking, while industries were insufficient to face the country’s challenges. To solve these problems, he argued, the state should have a greater role in economic development, instead of acting as a “mere moneylender.” Footnote 16 This meant that reconstruction and industrialization should be analyzed as one, since “there is no other way to recover lost value and economic depression than to augment production.” Footnote 17 Overall, to frame the earthquake as a problem of development will be crucial for Aguirre Cerda’s success, even if he could not do it exactly as he wanted.

The government’s plan was first presented by the president in a heartfelt speech in front of Congress on January 31, a week after the earthquake. According to Silvert (Reference Silvert1948), the bill was written hurriedly by the minister of finance, engineer Roberto Wachholtz, who was a strong supporter of state-led industrialization. It proposed a six-year plan for recovery, for which he asked Congress the authority to collect and spend 2.5 billion pesos over and above regular national revenue: 1 billion for reconstruction and relief, 1 billion for unspecified projects for industrial development, and 0.5 billion for public housing for urban workers. Part of this amount was to be obtained from new and increased taxes, part from reassignment of the national budget, and the remaining part from loans (mostly internal). Footnote 18 In this first version of the bill, the money would be managed by the Ministry of Finance.

The opposition was perplexed. Not only was the government asking for an extravagant sum for reconstruction—one billion pesos, equivalent to the whole public budget for a year—but Aguirre Cerda was also proposing a fundamental change in political economy. Immediately, opposition parties declared their complete hostility to the bill, publishing a “manifesto” against it, vowing to deny the president such powers and accusing him of playing with the future of the country. Footnote 19 Their argument was that the project exceeded the immediate problem of reconstruction, and that by requesting funds for yet unspecified projects the president was asking Congress to give up its constitutional right to supervise government spending. Footnote 20 Minister Wachholtz tried to convince the opposition, arguing that “we cannot conceive of asking for loans if we are not creating the means to pay them later.” Footnote 21 However, the opposition had the majority in the Finance Committee of the House of Deputies, and the bill was rejected. Footnote 22

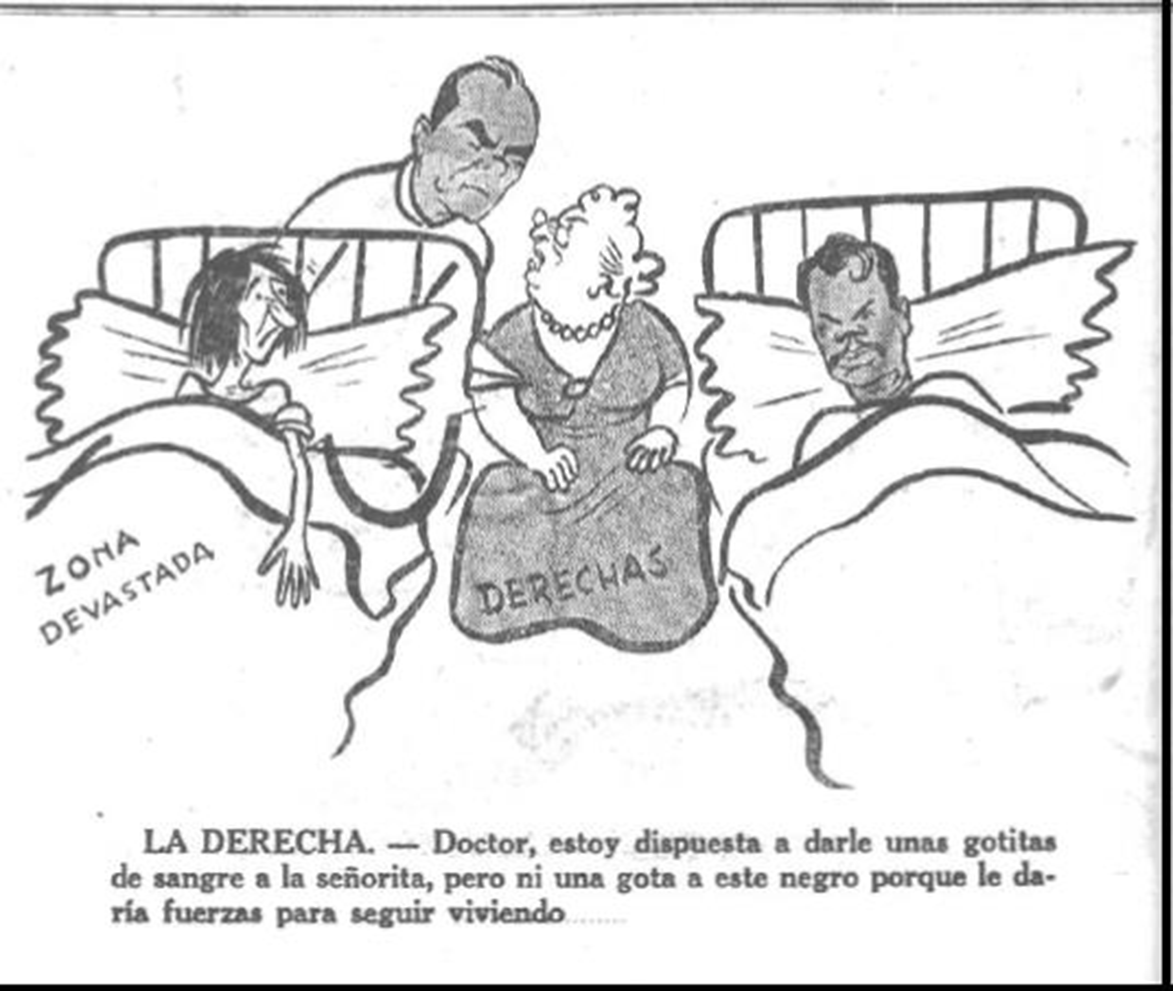

Aguirre Cerda’s plan shows us his economic ideas; what followed shows us his charismatic political style. To promote the bill, he urged popular support on national broadcast radio as he organized a second tour of the earthquake-torn provinces. “I have promised not only to bury your dead,” he claimed, “not only to help those wounded and homeless, but also to immediately face the reconstruction of devastated cities, to recover daily life and jobs, to save agriculture and industry.” Footnote 23 In this context, the administration started a large campaign to portray the opposition as responsible for the delay in disaster relief (see figure 2). “Of all the countries in the world, Chile is the only one that has not helped the victims of the Chillán earthquake,” claimed the political magazine Topaze (see additional files). Footnote 24 The narrative also evoked patriotism and solidarity, especially to justify the tax reform (Gil and Atria Reference Gil and Atria2021). As several authors have suggested, the Front actively encouraged sentiments of nationalism among their middle-class voters (Barr-Melej Reference Barr-Melej2001; Rosemblatt Reference Rosemblatt2000), and the disaster proved to be a great occasion to do so.

Figure 2. “Derechas,” Revista Topaze, February 17, 1939.

A second part of the strategy was to publish a list of projects that were part of the future development program. Most of these programs had been prepared in the previous decades by different technocratic groups of Chilean engineers. Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, engineers had emerged as an important stakeholder for the Chilean state: a so-called independent group of experts that challenged the state with new ventures, but also helped neutralize and legitimize several modernization projects (Ibáñez Reference Ibáñez1983; Silva Reference Silva2009; Nazer Reference Nazer2016; Harvey Reference Harvey2020). They were important economic and political actors because their expertise allowed them to mediate between industrialists and politicians (Ibáñez Reference Ibáñez1983; Harvey Reference Harvey2020). The first Latin American Conference of Engineering occurred in Santiago a week before the earthquake; the issue of electricity was prominent and a national plan for state-led electrification was presented at the conference (Humeres Reference Humeres2020). This plan was included in the development program, with the largest budget (500 million pesos), and was amply discussed in the press to provide confidence in CORFO.

What other plans were contemplated? By February 20 there were seven different reconstruction bills under discussion in Congress, including two from the conservative-liberal coalition and a second one from socialist and communist deputies, who presented alternative measures to collect funds. Footnote 25 For them, the taxes of the Aguirre-Wachholtz bill were misplaced; they opposed the increase on sales tax, instead proposing higher taxes on industrialists and landowners and the termination of payments on Chile’s external debt. However, the most fundamental critique came from the opposition, whose bills focused only on reconstruction, leaving aside the discussion about economic development. Footnote 26 The most comprehensive of these plans proposed the creation of a reconstruction corporation on top of emergency funds, a project that cost a third of the money required by the government’s proposal. Some of these concerns were incorporated in a new government bill, apparently presented by Wachholtz without consulting the rest of the cabinet. The request for 2.5 billion pesos was maintained, but the government made concessions in several points related to funds—internal loans and taxation were significantly scaled down—and proposed the creation of not one but two state organizations: the Reconstruction and Assistantship Corporation (CRA), to act in the most affected areas for up to six years, and the Production Development Corporation (CORFO), to address recovery at the national level. Footnote 27 The opposition, however, refused this bill as well, while the Finance Committee of the House passed a favorable report on their project. Footnote 28

Overall, the critical juncture triggered by the earthquake resulted in seven plans but two main options in terms of institutional trajectories: on one side, to address aid and reconstruction, leaving production to be discussed later; and on the other side, to include a state-led program for industrial development as part of reconstruction and recovery. At this point in the discussion, this meant creating either one or two new corporations.

Chileans seemed to side with Aguirre Cerda, and large crowds would gather at each train stop to hear him speak and condemn right-wing politicians for prolonging their suffering. Importantly, industrialists also supported the second Aguirre-Wachholtz bill, although with several reservations. The National Manufacturers Association (Sociedad de Fomento Fabril, SOFOFA) had argued for an industrialization program since the 1930s, as long as they had direct participation in economic planning (Ibáñez Reference Ibáñez1983; Lederman Reference Lederman2005). Hence, they were willing to concede to state-led industrialization as long as CORFO looked more like the National Economic Council they had been lobbying for. Now, they wanted to be included in both boards: CORFO and the CRA. They expressed these ideas to Minister Wachholtz, who used his constitutional authority to withdraw all projects from discussion (including his own).

While Aguirre Cerda was on tour, his allies were also working to get the votes needed. Frontist congressmen from the most-affected provinces organized meetings with their colleagues from the opposition. Footnote 29 Representatives of these municipalities also visited their congressmen and the press, asking for the “end of politicking.” Footnote 30 Wachholtz conferred with SOFOFA, the workers federation (Confederación de Trabajadores de Chile), the opposition, and his allies to find a “harmonic solution.” Footnote 31 On March 1, he submitted a new bill that increased concessions to these groups but maintained the spirit of the project: 2.5 million, two corporations, and a fiscal reform. Footnote 32 Under the new dispositions the state did not have total control over any of the new agencies; instead, they would be created as public but quasi-governmental corporations, with a board that included the heads of industrial organizations, professional unions, and labor leaders. Still, they would be state-led, and the state would hold 100 percent of the shares. Also, some proposed tax increases were scaled down; specifically, a 10 percent tax on homemade manufactured goods was cut out of the project, and certain taxes that applied to national companies were extended to large-scale foreign mining companies. Simultaneously, Wachholtz managed to assuage socialists’ concerns about the sales tax. Footnote 33

The support of industrialists was crucial for this new bill to succeed. However, most of the opposition parties remained unconvinced and were determined to obstruct the creation of CORFO. In the words of a conservative senator, “We may have lost the election, but we will win the earthquake.” Footnote 34 This time the bill was approved by the Finance Committee of the House (probably to avoid Wachholtz withdrawing all projects again). What followed was a massive, sometimes violent fight between supporters of the Popular Front and the opposition at the House. More than once, the discussion grew so heated that representatives had to be pulled apart before a brawl broke out. As a deputy of the opposition put it: “the tragedy has put to the test not only our economic capacity but also our aptitudes for democratic life.” Footnote 35 Finally, the bill was approved in the House thanks to the vote of the liberal deputy Armando Martín, who represented the district of Chillán. Footnote 36

For the Senate, the government used the same strategy. The Front organized massive rallies in Santiago, and Aguirre Cerda addressed the multitudes repeating a similar speech: economic expansion was vital for the reconstruction program and any hope of economic self-sufficiency. Footnote 37 However, the opposition did not relent. The Finance Committee of the Senate also criticized the “mixing” of the reconstruction and development corporations in the same bill, calling it a “vice.” Footnote 38 The project suffered several more changes, which meant that it had to go back and forth to the House several times. Aguirre Cerda fought hard for vetoing the motion to subject the development plans to Congressional approval and, in the end, the opposition´s biggest triumph was to deny the president his four special appointees on CORFO’s board of directors. Footnote 39

CORFO was finally approved on April 26, only a little more than three months after the quake. Footnote 40 How did the government manage to secure the votes? Some have argued that Aguirre Cerda stopped a bill to organize farmers’ unionization in exchange for CORFO (Muñoz and Arriagada Reference Muñoz and María Arriagada1977; Loveman Reference Loveman1979). The rumor started in 1939, but Aguirre Cerda denies this in his letters to Gabriela Mistral, assuring the renowned poet that the discussion of the bill was paused to better study the issue. Footnote 41 According to scholars who have studied countryside mobilization in Chile, Aguirre Cerda was not a great supporter of farmers’ unionization (Acevedo Reference Acevedo2015), fearing that it would hurt his plans for technologizing the countryside (see Aguirre Cerda Reference Aguirre Cerda1929). Loveman (Reference Loveman1979, 278) supports this hypothesis, adding that the earthquake had left men in the countryside “bordering on insurrection.” It is more likely that the price for CORFO can be found in the reconstruction bill itself: protectionist measures for Chilean industry, a quasi-governmental control of the CORFO board, and the termination of payments on Chile’s external debt (Correa et al. Reference Correa, Consuelo Figueroa, Rolle and Vicuña2001; Nazer Reference Nazer2016). It must also be considered that, in both the House of Deputies and the Senate, the crucial votes from the opposition parties were placed by representatives of the most affected provinces, who received strong criticism and even expulsion from their parties. Footnote 42 This indicates that the earthquake was, in fact, the crucial factor in passing the bill; because Chillán politicians were conscious of how delaying the bill was hurting their constituents, they felt the pressure from voters and were probably pushed by Wachholtz himself (Loveman Reference Loveman1979, 278). Overall, evidence points to the earthquake’s greater role in allowing Aguirre Cerda to succeed with the reconstruction and development bill. The disaster increased the need for public expenditure and set a new, higher expectation for state involvement in society, providing new evidence of a “displacement effect” in moments of crisis (Peacock and Wiseman Reference Peacock and Wiseman1967; Legrenzi Reference Legrenzi2004).

In the end, CORFO meant different things for different actors. Most frontists were happy, because its creation legitimized the idea of planning and the principle that government had the duty to intervene in economy and society to improve the living conditions of the people. Socialists interpreted it as a triumph of “capitalist” views inside the Front, and this would soon lead to several problems for Aguirre Cerda (Silvert Reference Silvert1948). Industrialists, who had representatives on the board of CORFO, were mostly hopeful, as they would get easier access to credit and saw an opportunity to participate in the development projects. In fact, Ibáñez (Reference Ibáñez1994) has shown that the sectoral plans led by CORFO during its initial years were heavily influenced by industrial leaders. Even so, part of the opposition was frustrated; they feared CORFO would mean a stronger and “meddling” state, and that is exactly what happened. The impact of this law on Chile’s technocratic state and its corresponding bureaucracy was significant (Ibáñez Reference Ibáñez1994; Silva Reference Silva2009). The number of public employees in the country rose by nearly one-sixth between 1937 and 1941. By 1957 this number had doubled compared with 1930’s capacity (Hurtado Reference Hurtado1966). The reconstruction and recovery program would also transform many sectors, from public health to childhood protection services (Rojas Reference Rojas2010; Pavilack Reference Pavilack2011), but the three main institutional outcomes were CORFO, the CRA, and the tax reform. These institutions and resources became tools for the state for years to come.

Institutional legacies

Critical junctures are important because they help us to understand events themselves, and because they allow us to rethink the relationship between events and social structure. As historical sociologist William Sewell stated (Reference Sewell2005, 199), for a certain social science, “it seemed that ‘event’ and ‘structure’ could not occupy the same epistemological space.” However, events can only be interpreted within the terms of the structures in place. At the same time, the study of events shows us that they can have the power to redefine structures (Sewell Reference Sewell2005; Wagner-Pacifici Reference Wagner-Pacifici2017). Comprehending this relationship has been difficult for sociology, and critical junctures can be thought of as an analytical tool for doing so because they allow us to understand that occurrences become events when they force us to make choices. Once choices are made, alternative options are closed off and institutional paths are set (at least for a while).

Critical junctures are particularly helpful for understanding the institutional trajectories of states (Soifer Reference Soifer2016). In fact, the 1939 earthquake had a positive impact on state strength. First, it boosted the institutionalization and professionalization of bureaucracies to implement policies and deliver public goods (institutional capacities). Second, it allowed the state to increase its extractive capacity. And finally, it increased the state’s capacity to penetrate throughout the territory (state reach). Footnote 43 To fully understand these outcomes, we need to analyze the long-term impact of the reconstruction bill.

Institutional capacities

The most visible institutional legacy of the 1939 earthquake is the development corporation, CORFO. It is clear from the literature on industrialization that only after CORFO, and thanks to CORFO, the Chilean entrepreneurial state started to dominate economic activity in the country, playing a direct or indirect role in most economic sectors (Meller Reference Meller1996; Lederman Reference Lederman2005; Bravo-Ortega and Eterovic Reference Bravo-Ortega and Eterovic2015). However, developing and promoting a national production and development plan turned out to be more difficult than expected, due to a lack of data on industrial and economic activities.Footnote 44 Also, the global scenario set by World War II posed important challenges for importing the equipment needed to create certain industries. Hence, during the first four years, CORFO focused on generating capacities for monitoring industries and ensuring supplies for Chilean companies. Footnote 45 Still, the already mentioned Immediate Action Plans were put into motion, including a major electrification plan that would transform the country (Humeres Reference Humeres2020). By 1943, CORFO had invested US$5 billion dollars in energy (34.2 percent), manufacturing (25.3 percent), agriculture (15.4 percent), transportation (13.1 percent), and mining (12 percent).Footnote 46 By 1945, 30 percent of the country’s total investment in industrial equipment was through CORFO (Jones and Lluch Reference Jones and Lluch2015). By the 1970s, CORFO had created fifty-three new companies, from the Compañía de Aceros del Pacífico (steel company) to Chile-Films (film production company).Footnote 47 The number of people hired in the manufacturing sector changed accordingly: from 15 percent of the active population in 1930 to 18 percent in 1952. The same effect can be seen in mining, where the production of nitrates no longer surpassed copper (Hurtado Reference Hurtado1966, 26). Not surprisingly, though in 1930 the percentage of people living in rural areas still surpassed those living in cities (49 percent), by 1960 a majority of the population (64 percent) would live in urban centers (Geisse and Valdivia Reference Geisse and Valdivia1978, 24). Over the years, CORFO has played different roles in different periods of Chilean history but always has had a leading role in industrial development.Footnote 48 Today, CORFO has a budget of about one billion dollars to oversee different programs aimed at generating sustainable economic development through investment, innovation, research, and entrepreneurship.Footnote 49

Time will give more relevance to CORFO, but it is in the reconstruction corporation, the CRA, that we can first see a stronger Chilean state. The opposition was so immersed in the fight over CORFO that they failed to realize the newfound power the CRA gave to the state. The press also tended to downgrade the CRA’s role in reconstruction, with newspapers attributing several of its housing projects to CORFO, to the dismay of its director. Footnote 50 However, the CRA was responsible for assistance to victims and rebuilding of infrastructure in the zones directly affected by the earthquake. This included producing houses, lending money to build houses, and using its ability to design new urban plans for the cities destroyed, leaving local governments (municipalities) as a consulting body. Its power included the administration of the loans for reconstruction and the authority to declare eminent domain over any piece of land that was needed to fulfill its mandate (Behm Rosas Reference Behm Rosas1942). The reconstruction law inadvertently gave the state the right to design cities and organize the territory as never before in Chilean history, at least in the six provinces defined in the law as the reconstruction zone.Footnote 51 Other provinces were added over the years after consecutive minor earthquakes (1943, 1945, 1949), fires (1943, 1947), and a volcanic eruption (1943) affected other areas, and its mandate was extended to 1958 under the name Reconstruction Corporation. During these years, the CRA created 6,759 new houses: 5,125 via loans and 1,454 through direct construction (Arriagada Reference Arriagada2005, 83). It also constructed 2,113 emergency homes that lasted much longer than they were designed to last (Bravo Reference Bravo Heitmann1959). Finally, by 1953 it was merged with the Housing Credit Union (Caja de Habitación Popular) into the autonomous and permanent Housing Corporation (Corporación de la Vivienda, CORVI). Footnote 52 Literature on state building has documented this tendency of institutions created in the context of a threat to self-perpetuate, calling it a ratchet effect (Tilly Reference Tilly, Peter Evans and Skocpol1985). When new bureaucracies are created it is very unlikely that they will disappear after the threat is over (Tilly Reference Tilly, Peter Evans and Skocpol1985; Legrenzi Reference Legrenzi2004).

At Chillán, we can see this new configuration of forces in place. The city was completely destroyed, opening a window of opportunity for reconsidering the urban landscape. As mentioned, events can be thought of as ruptures in which physical and social structures are tested (Wagner-Pacifici Reference Wagner-Pacifici2017). Consequently, reconstruction is not just about replacing infrastructure but is a process driven by the need to rearticulate society. At Chillán, this translated into several plans and maps for a new city, with diverse ideas about what to redo and what to change. By March 16, at least four projects had gained some attention (and another four for the city of Concepción). Footnote 53 Among these were the plans of the newly formed Association of Landowners (Asociación de Propietarios), which very much wanted to maintain the original property lines in order to rebuild their homes and businesses in place immediately. Footnote 54 Yet, according to the new law, reconstruction and city planning was in the hands of the central state, specifically the CRA and the Ministry of Public Works (Ministerio de Obras Públicas). Led by the architect Luis Muñoz-Maluschka, the state planned renewed cities under the guidelines of modernism, with wider streets, monumental buildings, diagonal avenues, and new parks (Torrent Reference Torrent2016; Aguirre Reference Aguirre2004). The municipality supported the neighbors and opposed the plan, complaining that the proposed zoning for the city was “Prussian,” but the local government had little to say in the matter. Footnote 55 After strong negotiations (described in Carvajal Reference Carvajal2011 and Torrent Reference Torrent2016), the state’s ambitious plan was gradually reduced to maintain part of the original spatial configuration of the city. However, the final city plan was designed in Santiago, maintaining quite a lot of the modernist aim.

In summary, the institutional capacities of the state were strengthened by the reconstruction law, even beyond the worst fears of the opposition. Not only was CORFO directly involved in industrialization, but the earthquake also helped the development of housing policies, inaugurating a new relationship between the state and local governments in terms of urban planning.

Extractive capacity

As Tilly (Reference Tilly, Peter Evans and Skocpol1985, Reference Tilly1990) has masterfully described, bureaucracies interact with taxation to shape state building. Congruently, the creation of CORFO and the CRA meant an increased demand for fiscal income that was met, in part, by a comprehensive tax reform. This reform included several changes in income tax; a 2 percent increase on income from property tax, 2 percent on industry and commerce, 2 percent on mining activities, and 1 percent on other sources of income (Gil and Atria Reference Gil and Atria2021). Additionally, a 50 percent hike on the inheritance tax was included, together with new taxes in agriculture and new patents for mining activities. The reform disproportionally affected the international copper-mining companies that operated in the country, since certain taxes that applied to national companies were now expanded to include them (Gil and Atria Reference Gil and Atria2021). Furthermore, this clause was retroactive in practice and included the gains for 1938 (not yet reported). Footnote 56 Overall, the reform did not radically change the fiscal structure of the country, but its impact was slightly progressive: revenue from income tax and property tax increased from 1939 to 1940 and continued to do so in the following years (Gil and Atria Reference Gil and Atria2021). Importantly, several of the taxes that were defined as temporary by the reconstruction law (with a sunset clause of one or five years) ended up becoming permanent. Footnote 57 This is another example of a ratchet effect in state building during emergencies: taxes that rise abruptly during a crisis do not “sink” to pre-crisis levels (Tilly Reference Tilly, Peter Evans and Skocpol1985, 180).

Admittedly, CORFO acquired significant international debt over the years, mainly from the Export-Import Bank, and especially after 1947.Footnote 58 Still, the credits granted by the American bank were made directly to the corporation and not the state, since Chile had terminated its external debt payments and was ineligible. Footnote 59

Spatial reach

Reconstruction efforts also had a positive effect on another aspect of state strength: the ability to “project power over distance” (Herbst Reference Herbst2014, 173). One commonly used measure for this analysis is road density, since roads are considered a prerequisite for the expansion of police offices, schools, medical centers, the postal service, or phone lines. In other words, public roads are vital to the exercise of formal authority (Herbst Reference Herbst2014). In the case of Chile, by 1939 many towns had no public access road besides the paths that the conquistadores had settled hundreds of years before.Footnote 60 This precarious situation had worsened due to the disaster. According to one of the first sets of data gathered by CORFO, there were one thousand fewer kilometers of roads available in 1940 than in 1939 (Díaz et al. Reference Díaz, Lüders and Wagner2016). This was particularly important for the development plan, since there was “no point in organizing industries if there are not routes to move the products.” Footnote 61 Reconstruction, then, brought about an extensive program of transportation, and road density increased substantially in the following years: from 41,785 kilometers in the 1937–1939 period, to 44,440 kilometers in 1942, and 47,420 more kilometers in 1945, a 13 percent increase in five years (Díaz, Lüders, and Wagner Reference Díaz, Lüders and Wagner2016). As mentioned, the reconstruction plan had a relevant impact on several social programs developed by the Front, and transportation is a good example of this. Furthermore, studies in state building allow us to see road construction as way to expand state reach.

Final discussion

The Chillán earthquake of 1939 happened during an important time in Chilean history, concurrently with relevant global events such as World War II. A British newspaper addressed the parallel brilliantly: “The land is fertile and rich in minerals, but unfortunately, there is a price to pay: this shelf above the Pacific deeps in the direct line of one of the greatest earthquake belts in the world. The inhabitants of Chile, therefore, expect occasional earthquakes as we in Europe have come to expect occasional wars.”Footnote 62

In this article, I have explored this theoretical connection. War making was crucial to shaping state building in Western Europe (Tilly Reference Tilly, Peter Evans and Skocpol1985, Reference Tilly1990; Peacock and Wiseman Reference Peacock and Wiseman1967; Legrenzi Reference Legrenzi2004; Soifer Reference Soifer2016); this research suggests that other type of battles or threats, such as socio-natural disasters, can have a similar effect, prompting the creation of new bureaucracies and administrative bodies, along with the development of new regulations to increase state revenue to pay for these institutions, and expanding the state’s presence in the territory. In the case of earthquakes, the parallel with wars also includes the problem of debris; since both events can pose similar reconstruction challenges. Thus, broadening our understanding of what constitutes a relevant political event by including environmental shocks can be especially important for the study of state development in Latin America.

However, it is important to note that historical institutionalism has concluded that reconstruction challenges can only provide opportunity to states that have the minimal capacities to be able to capitalize on them; this helps explain why disasters in other contexts can have very different effects. In the case of the 1939 Chillán earthquake, the Chilean state was strong enough to survive the shock, and President Aguirre Cerda certainly knew how to make the most of it. So did Minister Wachholtz, who years later confessed to an American graduate student that he had known they were taking advantage of the situation, even if their argument about the need for development to ensure recovery was an honest one. Footnote 63 In the same interview, the minister described Aguirre-Cerda’s immediate words to him after the final vote in Congress: “You have given me a state within a state” (quoted in Silvert Reference Silvert1948, 13). This suggests that Aguirre Cerda understood the relevance of the reconstruction-development law, as described in this article.

Aguirre Cerda could not finish his period as president of Chile due to his premature death in 1941. Today, he is remembered for his famous campaign slogan “Gobernar es educar” (to govern is to educate). However, scholars of the Front—both those who are critical and those who admire it—agree that the greatest accomplishment of his government was the reconstruction and development bill, or more specifically CORFO (Stevenson [1942] 1970; Super Reference Super1975). The years after the earthquake were difficult for the president: an attempted military coup, the fears of armed intervention afterward, the exit of the socialists from the Popular Front, a fight with his own party, the early closing of Congress in 1940, the withdrawal of the liberal and conservative candidates from the general elections of 1941, and lastly, tuberculosis. As a consequence, Aguirre Cerda mostly failed to complete his ambitious presidential program. Out of twenty-two bills he sent to Congress in the year after the reconstruction and recovery bill was approved, none reached a vote (Super Reference Super1975). This shows that no matter how popular and visionary Aguirre Cerda was, it took the earthquake to trigger a critical juncture for him to move forward with a state-led industrialization plan. CORFO was made possible by the moment of fluidity that the disaster unlocked, and it could not have happened as it did, or when it did, if not for the earthquake.

Finally, it is important to highlight that the case shows the strong potential of using the critical juncture framework for the study of disasters’ impact in the political realm. For this, it is necessary to take disasters seriously as a category, that is, to understand disasters as events that have the power to disrupt economic, social, or political equilibriums, thus forcing rearticulations. As a result, disasters can call into question implicit or explicit agreements, lead to periods of renegotiation of institutions, and give actors the opportunity to make “momentous” decisions.

Supplementary material

To view additional files for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lar.2022.53

Acknowledgements

My profound thanks to Karen Barkey, Luis Maldonado, and Cecilia Correa, who made important suggestions at various stages in the development of this research; and to Carmen Zañartu, who survived the earthquake and helped me understand what it meant. Additional thanks to the anonymous reviewers at Latin American Research Review for their constructive comments, and to the different librarians who helped me get access to archives during pandemic times. The research for this article was supported by the Chilean National Research and Development Agency (ANID) under Fondecyt Regular Grant number 1191522, with the continuous support of CIGIDEN (ANID/FONDAP/15110017) and the Observatory of Social Transformations (ANID/PCI/Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies/MPG190012).

Magdalena Gil is assistant professor at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile School of Government and a researcher at the Center for Integrated Disaster Risk Management (CIGIDEN). She received her PhD from Columbia University in 2016. Dr. Gil specializes in disasters and their impacts on state and society. Her current research focuses on public policy and climate change adaptation.