Prominent research argues that differences in ethnic group characteristics increase the likelihood of civil conflict and separatism (Bormann, Cederman, and Vogt Reference Bormann, Cederman and Vogt2017; Caselli and Coleman Reference Caselli and Coleman2013; Esteban, Mayoral, and Ray Reference Esteban, Mayoral and Ray2012; Vogt Reference Vogt2018). Language is a key ethnic attribute in many of these accounts: ethnic groups with distinct languages are more likely to engage in conflict with other groups or a central state, as are groups that have many members who speak their “native” language. However, there is increasing evidence that this limited conceptualization of language—that it mainly serves to intensify the effect of ethnicity—belies its independent importance to identity and political outcomes, including national identity and separatism (Marquardt Reference Marquardt2018; Onuch and Hale Reference Onuch and Hale2018; Pérez and Tavits Reference Pérez and Tavits2019; Pop-Eleches and Robertson Reference Pop-Eleches and Robertson2018; Rodon and Guinjoan Reference Rodon and Guinjoan2018; Siroky et al. Reference Siroky2021).

There are theoretical reasons to believe that language, in and of itself, may be important for separatism. Traditional ethnic theories of separatism hold that the individuals most likely to engage in conflict with the central state are those who: (1) share an identity; (2) perceive blocked social mobility; and (3) have less access to state institutions (Cederman, Gleditsch, and Buhaug Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug2013; Cederman, Wimmer, and Min Reference Cederman, Wimmer and Min2010; Gellner Reference Gellner1983; Gurr Reference Gurr1993). Language fulfils all three of these criteria: it is fundamental to the development of a common identity (Anderson Reference Anderson2006), and speaking the language of a central state can be essential for social mobility and access to state institutions (Laitin and Ramachandran Reference Laitin and Ramachandran2016; Marquardt Reference Marquardt2018). This link between language and theories of separatism yields several clear empirical expectations. First, individuals who only speak the language of a peripheral region should be those most likely to support separatism: they share a peripheral linguistic identity, and due to their lack of fluency in a central language, they potentially face blocked mobility and difficulty accessing resources in the central state. Second, individuals who speak the language of the central state should be less supportive of separatism since they: (1) share an identity with the center; and (2) face neither linguistic blocked mobility nor hindrances in accessing state institutions in the center.

This logic stands in contrast to the traditional approach to language in studies of ethnic separatism: language has a direct link to separatist sentiment, independent of its relationship to ethnic identity. An individual's linguistic preferences over separatist outcomes may, in fact, run counter to their ethnic preferences: a member of a peripheral ethnic group who only speaks the language of the central state may oppose separatism given the linguistic advantages integration with the central state provides them. Equally importantly, the language(s) most relevant for separatism may not even be linked to a particular ethnic group: a peripheral lingua franca may be more relevant for day-to-day life than ethnic languages and thus more salient for separatism.

In this article, I investigate the relationship between language, ethnicity, and support for separatism using original survey data from two Eastern European regions, both de jure territorial units of the post-Soviet state of Moldova: the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (Pridnestrovie, also known as Transnistria) and Gagauz Yeri (Gagauzia). The Slavic Russian language is both a lingua franca and the language most closely linked to social mobility in both regions. The language of the central state, Moldovan (a Romance language), is of limited utility in both Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia but is increasingly essential in Moldova proper. These two regions thus provide a context in which language is likely to be salient for separatism: speakers of Russian have greater opportunities in these regions than they do in Moldova proper and have a common linguistic identity distinct from that of the population of the central state.

Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia also provide analytic leverage for disaggregating the influence of language from ethnic identity. Specifically, a non-Moldovan ethnic group represents the plurality or majority population in both regions: Russians constitute at least 30 per cent of the population of Pridnestrovie, while the Turkic Gagauz constitute over 80 per cent of Gagauzia's population. If a sense of ethnic kinship is most relevant for separatist sentiment, members of these peripheral ethnic groups should be most supportive of separatism. If language intensifies ethnic sentiment, then ethnic Russians who speak only Russian and ethnic Gagauz who speak Gagauz—not Russian—should most support separatist outcomes.

Analyses of observational data indicate that language has a stronger relationship with support for separatism than does ethnic identification: in both regions, speakers of the main peripheral language (Russian) are the most supportive of separatist outcomes, regardless of their ethnic affiliation. Moreover, monolingual speakers of a peripheral language linked to ethnic identity (Gagauz in Gagauzia) are less supportive of separatism than speakers of the main peripheral language (Russian).

While these results are congruent with claims about the importance of language to separatism, causal identification remains a concern. In addition to a case selection that facilitates disaggregating language from ethnic identity—the most likely confounding variable—I engage with identification in two ways. First, I analyze a survey experiment that primed respondents to consider their linguistic abilities prior to reporting support for separatism. Results from the experiment indicate that linguistic abilities—not identification with an ethnic group—account for the relationship between language and support for separatism. Second, the Online Appendices contain detailed observational analyses illustrating that factors related to identity do not directly determine linguistic proficiency.

If we are living in an “age of secession” (Griffiths Reference Griffiths2016), then understanding why individuals support separatist outcomes is of vital importance. This article contributes to this literature in two main ways. First, peripheral lingua francas have played a role in separatist mobilization around the world, with cases ranging from Russian across the former Soviet Union, to English in the Ambazonia region of Cameroon. This article provides insight into this phenomenon by illustrating how a peripheral lingua franca (Russian) can unite individuals of different ethnic backgrounds to support separatist ends. Second, while peripheral linguistic and ethnic identities are more difficult to disentangle in many important cases of separatism—such as Catalan in Catalonia and Tibetan in Tibet—this article demonstrates that language is conceptually and empirically distinct from ethnic identity. Moreover, the analyses in the article show that language can be more salient for separatism than ethnic identity. Together, these results indicate that conflating language and ethnicity risks fundamentally misidentifying the roots of separatism, even in cases where these concepts overlap.

Ethnicity and Sparatism

Separatism is a matter of territory: a peripheral population demands greater autonomy or independence for their region. Scholars generally assess a region's identity-based propensity for separatism by focusing on the relative opportunities that separatism offers members of peripheral ethnic groups.Footnote 1 Primary explanations are: (1) blocked social mobility; and (2) differential access to resources. Gellner (Reference Gellner1983) holds that the ethnic groups most likely to engage in separatism are those that face permanently blocked social mobility: members of these groups believe they will never have equal opportunities as long as they are part of a state dominated by another group. Scholarship associated with the Ethnic Power Relations project argues that co-ethnicity with a state's leadership determines access to state resources; excluded groups have no such access and are thus most likely to engage in conflict (Cederman, Wimmer, and Min Reference Cederman, Wimmer and Min2010).

The explanation of why ethnicity—as opposed to other social identities—serves as the mobilizing nexus for separatism varies. However, a common thread is that ethnic identity is uniquely powerful in imbuing a sense of common experiences and purpose among its members. For example, Hale (Reference Hale2008) proposes that ethnic groups are particularly likely to solve the commitment problems inherent in separatism; members of these groups believe that co-ethnics share their preferences due to similarities in tangible characteristics and more intangible shared culture. As a result, they can reasonably believe that the leadership of a state in which members of their group dominate will act in accordance with their interests.

Ethnic Attributes and Separatism

Another body of literature argues that a focus on ethnicity writ large belies substantial intra- and interethnic variation in ethnic identity salience. This argument has important implications for understanding purportedly ethnic separatism. For example, Chandra (Reference Chandra2006; Chandra Reference Chandra2012, 1–178) notes that many theories of ethnic politics focus on attributes that make ethnic identity particularly salient, for example, physical traits that are difficult to change and noticeable. If the identities marked by these attributes are linked to social mobility, their noticeability and unchangeability make them highly salient. Since social mobility is an integral element of many accounts of separatism, such attributes are of clear relevance to determining if members of an ethnic group support separatism.

However, there is no prima facie reason to believe that all of these attributes must be “ethnic” in the sense of being descent-based. This claim is particularly true in the case of peripheral identity, where proximity may lead members of different groups to exhibit similar attributes through intermarriage or, as I argue, similar linguistic repertoires.Footnote 2 As a result, attempts to measure peripheral identity by identification with a demographically dominant ethnic group may miss the more important attributes that unite or divide residents of a peripheral region.

Language and Separatism

I argue that language is an attribute that: (1) has a clear link to ethnic theories of separatism; and (2) is conceptually and empirically distinct from ethnic identity, cutting across and within ethnic divides. The theoretical link between language and separatism is twofold. First, scholars have long noted the importance of language for developing a common national identity (Anderson Reference Anderson2006; Liu Reference Liu2015; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2018) or other politically salient identities among otherwise disparate communities (Laitin Reference Laitin1998). Second, an individual's linguistic repertoire is also difficult to change and noticeable (Marquardt Reference Marquardt2018). As a result, linguistic fluency sends a strong signal of group membership—be it of the central or peripheral group. Even if language does not determine membership in high-prestige groups, it is still generally necessary for social mobility: knowledge of high-status languages can determine access to important institutions. For example, if an individual does not speak the language of business in a society, they will have difficulty finding high-paying employment. As a result, individuals have a strong incentive to reside in a region where their language is prestigious and supported by the state, regardless of its identity content.

For both of these reasons, an individual's linguistic repertoire has a clear link to regional sovereignty and thus separatism. If an individual faces discrimination because they do not speak the central language, or if they cannot find employment for the same reason, they have a strong incentive to support greater sovereignty in a region where their colinguals dominate. As a corollary, if proficiency in a peripheral language is essential for membership in a peripheral identity group, a nonspeaker of this language will have little incentive to support regional sovereignty. Indeed, if they speak the central language, they have strong reason to support greater integration with the center.Footnote 3

Other work on language and separatism generally uses language to proxy strength of ethnic identification (Bormann, Cederman, and Vogt Reference Bormann, Cederman and Vogt2017; Hale Reference Hale2008), positing that an individual who identifies with the language of their group (for example, considers it their “native” language) identifies to a greater extent with their group than a co-ethnic who does not. In contrast, I argue that the key aspect of language is proficiency, which facilitates membership in the identity groups to which a language is linked and allows access to resources that require linguistic knowledge.

The focus on identification with ethnic languages is thus potentially misleading. Unlike ethnic attributes, linguistic repertoires are not descent based. Parents have a strong incentive to teach their children the language of a central state or a regional lingua franca in order to ensure that they are able to communicate with other residents of their country or region, as well as access state services. If these languages are linked to membership in a high-status group, encouraging capabilities in these languages is of even greater importance (Laitin Reference Laitin1998). As a result, children often have a different linguistic repertoire than their parents and may not even develop competencies in their ethnic language, even if they identify with it. Linguistic fluency thus cuts across ethnic boundaries and creates linguistic identities—and thus preferences over separatist outcomes—distinct from their ethnic counterparts. Indeed, the language most salient for separatism may not even be ethnic, in the sense of being most closely linked to a regionally dominant ethnic group: if there is another peripheral language (for example, a lingua franca) that is more important to an individual's day-to-day life and social mobility in the peripheral region, this language will be more salient for separatist sentiment.Footnote 4

Separatism in Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia

I examine the link between language and separatism using two cases, both regions of the former Soviet republic of Moldova: Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia (see Figure 1). Both Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia had separated from the then Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (MSSR) by 1991.Footnote 5 While Gagauzia reintegrated with the newly independent Moldova as an autonomous territorial unit in 1994, Pridnestrovie has remained de facto independent after a war with Moldova proper that ended in a 1992 ceasefire agreement. While separatism in both regions—in particular, Gagauzia—could plausibly have ethnic origins, linguistic dynamics provide a compelling alternative explanation. Moreover, historical circumstances in these regions have yielded a situation in which it is possible to disaggregate language from ethnic identity to a greater extent than is often possible, providing leverage for analyzing the effect of both ethnic identity and language on separatist sentiment.

Fig. 1. Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia.

Note: Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia are shaded in black.

Ethnicity and Separatism in Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia

Following from the highly ethnicized Soviet system (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1994; Slezkine Reference Slezkine1994), work on separatism and conflict in the former Soviet Union has emphasized the presence of a concentrated peripheral population in determining patterns of nationalist mobilization in the 1980s and 1990s (Hale Reference Hale2000; Hale Reference Hale2008; Toft Reference Toft2005).Footnote 6

Given this context, Gagauzia appears to be a typical case for separatism: it is the homeland of the Turkic Gagauz people, and ethnic Gagauz represent the overwhelming majority of its population. In contrast, Moldova proper is largely ethnically Moldovan, and its nationalist movement had strong chauvinist tendencies during the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Moreover, the Gagauz have a history of grievances against Moldovans (Katchanovski Reference Katchanovski2005; Katchanovski Reference Katchanovski2006); work on horizontal inequalities would suggest that they are likely to engage in separatism since they are also a politically excluded group in a relatively poor region (Cederman, Gleditsch, and Buhaug Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug2013; Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000).

Pridnestrovie is perhaps a less typical case of ethnic separatism. At the time of the region's declaration of independence, its population was roughly equally divided among ethnic Moldovans, Russians, and Ukrainians. In fact, ethnic Moldovans constituted a slight plurality of the region's population. Nevertheless, scholars link Pridnestrovian separatism to Russian identity, with Russians constituting approximately 30 per cent of Pridnestrovie's population in 1991. For example, Laitin (Reference Laitin2001) argues that Pridnestrovian separatism is a case of a “triadic nexus” (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996): an external homeland (Russia) provided support for a minority population (Russians) in a nationalizing state (Moldova). Indeed, the role of Russia in Pridnestrovian separatism is undeniable: Russian military intervention cemented Pridnestrovie's de facto independence; and Russia's continued ties with the region are of utmost importance to its economic and political system.Footnote 7 As a result, integration with Russia is perceived to be a plausible outcome for Pridnestrovian separatism: when Pridnestrovie held a referendum on independence in 2006, 97 per cent of voters supported independence followed by integration with Russia (TsIK PMR no date).

Language and Separatism in Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia

Linguistic dynamics provide a compelling alternative explanation for separatism in Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia: Russian is the peripheral lingua franca in both regions, while Moldovan is the dominant language of the central state, Moldova.Footnote 8 In this context, Russian speakers should support separatism, while Moldovan speakers should oppose this outcome.

Patterns of separatism in the 1990s indicate that this explanation is plausible. Moldovan nationalists in the late 1980s demanded a greater role for their language in Moldovan affairs, a stance that drew opposition from speakers of other languages, including much of the population of Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia (Crowther Reference Crowther1991). Indeed, the 1989 Moldovan Law on Languages—which named Moldovan the sole state language of the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic and demoted Russian from its state language status to a “language of interethnic communication”—directly preceded both regions declaring themselves no longer subordinate to Moldova (King Reference King1999; Skvortsova Reference Skvortsova and Kolstø2002).

The importance of the Russian language points to holes in ethnic explanations for separatism in Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia. There is strong evidence that separatism in Pridnestrovie was a multiethnic phenomenon, with support from both Moldovans and Ukrainians. Instead of ethnicity, the Russian language united the Pridnestrovian population in opposition to the Moldovan center (King Reference King1999; Kolstø and Malgin Reference Kolstø and Malgin1998; Petersen Reference Petersen and Chandra2012; Skvortsova Reference Skvortsova and Kolstø2002). In contrast, Moldovan was of limited use in the region, with education in the language only available in regions with compact settlements of ethnic Moldovans (Chinn and Roper Reference Chinn and Roper1995).

If language is important solely as a symbol of ethnic identity, then the Gagauz language should have played a role in Gagauz separatism similar to that which Russian played in Pridnestrovie. Indeed, the nationalist organization Gagauz Halkı, which stood at the forefront of Gagauzia's sovereignty movement, had agitated for raising the status of the language (Zabarah Reference Zabarah2012). However, the Gagauz language did not play a prominent role in social mobility in Gagauzia until the mid- to late 1980s: up to this point, only Russian and Moldovan were taught in schools, and there was no Gagauz-only media. As a consequence, many Gagauz were more comfortable in Russian than Gagauz (Chinn and Roper Reference Chinn and Roper1998). Russian was thus the lingua franca in the region, and defending the Russian—not Gagauz—language garnered widespread support for Gagauz sovereignty (Chinn and Roper Reference Chinn and Roper1998; Zabarah Reference Zabarah2012).

The importance of the Russian language in both regions has continued, even as the Moldovan language has assumed a greater role in Moldova proper. Russian-speaking Pridnestrovians have particularly strong incentives to support regional sovereignty since reintegration with Moldova could endanger the relatively privileged status of their language: Moldovan, Russian, and Ukrainian are state languages of Pridnestrovie, while neither Russian nor Ukrainian has such status in Moldova proper. Accordingly, data from a 2013 survey illustrate that a majority of Pridnestrovians believe that the Pridnestrovian government is more supportive of the Russian and Ukrainian languages than the Moldovan government, and that these languages are more frequently used in Pridnestrovie than Moldova proper; the opposite results hold for the Moldovan language.Footnote 9 Evidence from focus groups demonstrates that these linguistic perceptions have political implications, with Russian speakers citing linguistic concerns when discussing reintegration with Moldova (Beyer Reference Beyer2011).

A similar situation has emerged in Gagauzia. Although Gagauzia's formative documents (for example, its constitution) call for raising the status of the Gagauz language, Russian (and Moldovan) has equal formal status in the region. As in Pridnestrovie, 2013 survey data indicate that a large majority of Gagauz respondents believe that the regional government supports the Russian and Gagauz languages more than the Moldovan government, and these languages are more frequently used in the region; they report the opposite vis-à-vis Moldovan. These data also indicate that Russian use remains as common as that of Gagauz, if not more so: 21 per cent of respondents consider Russian more widely used than Gagauz, compared to 12 per cent who believe the opposite. In line with their linguistic affinities, residents of Gagauzia have also shown notable pro-Russian tendencies. For example, in a 2014 regional referendum, Gagauzia residents supported Moldova entering the Russia-backed customs union and were against further integration with the European Union; they also backed contested regional legislation granting Gagauzia the right to secede should Moldova lose its status as an independent country (Regnum 2014).

Empirical Analyses

The preceding discussion yields clear implications for analyses of support for separatism in both regions. Ethnic theories of separatism hold that members of peripheral groups—Russians in Pridnestrovie and Gagauz in Gagauzia—should be the most supportive of separatism, while members of the dominant group of the central state—Moldovans—should be the least supportive of this outcome. In contrast, a theory of separatism that focuses on language would argue that speakers of Russian—the main peripheral language in both regions—should be the most supportive of separatism, while speakers of Moldovan—the language of the central state—should be the least supportive of this outcome.

This linguistic explanation also has implications for secondary languages in both territories: Gagauz in Gagauzia and Ukrainian in Pridnestrovie. Ethnic theories of conflict generally hold that language is a symbol of ethnic identity (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000). The Gagauz language should thus be the most salient language for separatism in Gagauzia. In contrast, a linguistic theory would hold that the most salient language should be that which is most important for day-to-day life. As a result, Russian proficiency should be a stronger predictor of support for separatism than Gagauz.

In Pridnestrovie, Ukrainian proficiency is largely restricted to ethnic Ukrainians, who constitute less than a third of Pridnestrovie's population. Unlike Russian, it is not a peripheral lingua franca and is thus less relevant to social mobility in the region. However, the Ukrainian language is protected in the region and not in Moldova proper. Ukrainian speakers should therefore tend to support separatism, though to a lesser extent than Russian speakers.

To examine these empirical expectations, I conduct statistical analyses of original 2013 survey data from both Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia. The analyses proceed as follows. First, I discuss the data with a focus on the identification of linguistic effects. Second, I use observational data to analyze linguistic and ethnic correlates of support for separatism, finding that proficiency in the main peripheral language (Russian) is strongly correlated with support for separatism in both regions. Third, I provide experimental evidence that the relationship between language and support for separatism is, in fact, linguistic: linguistic primes increase the salience of linguistic—not ethnic—correlates of separatism.

The Data

The survey employed a computer-assisted personal interview strategy, and respondents had the opportunity to take the survey in any of the three official languages of their region. The Pridnestrovian sample includes 577 respondents (25 per cent response rate), while the Gagauz sample includes 836 (35 per cent response rate).Footnote 10

Ethnicity and Language in Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia

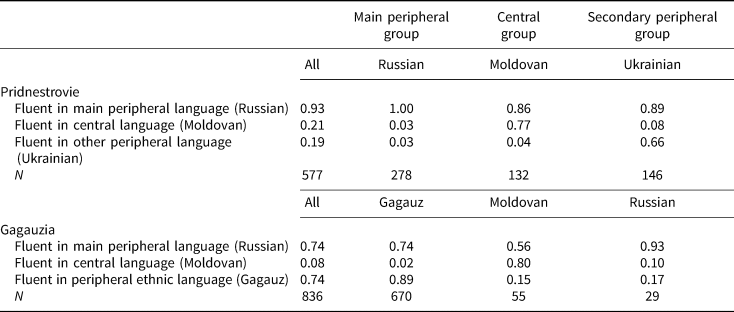

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics regarding the relationship between language and ethnicity in both regions. As a measure of ethnic identity, I use a dichotomous indicator of the ethnic group to which a respondent reports primarily belonging.Footnote 11 To measure whether or not an individual is fluent in a language, I dichotomize responses to a five-point Likert scale question that asks the respondent to report their level of spoken proficiency in Russian (the main peripheral language in both regions), Moldovan (the central language), and Ukrainian/Gagauz (secondary peripheral languages). I use the highest level—“I am fluent”—as the indicator of fluency. Columns represent different ethnic groups, with “All” representing all respondents in a given region and the remaining columns presenting data from members of groups linked to regionally relevant languages. Rows represent the proportion of respondents of different groups who report speaking different languages fluently.

Table 1. Distribution of linguistic fluency across ethnic groups in Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia

The data reveal that Russian functions as a lingua franca in both regions, with a majority of members of all ethnic groups reporting fluency in the language. Other languages—Moldovan and Ukrainian in Pridnestrovie, and Moldovan and Gagauz in Gagauzia—show a stronger connection to ethnic identity: it is generally members of these groups who report speaking their languages fluently. However, there is substantial variation within these groups in terms of fluency in their respective native tongues. This combination of widespread fluency in Russian and intraethnic variation in native language fluency allows for the disaggregation of language from ethnic identity in analyses of support for separatism.

Identification and Measurement of Linguistic Fluency

Although there is substantial intra- and interethnic variation in linguistic fluency in both Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia, identifying the effect of language remains a concern: a variety of factors—in particular, identity—could determine both the language(s) in which an individual is fluent and their preferences over separatist outcomes. I have engaged with these identification concerns in three main ways. First, I include the clearest potential confounding variable (ethnic identity) in all regression analyses of observational data. Second, I also analyze experimental data regarding the salience of language (versus ethnic identity) for support for separatism. Third, the Online Appendix contains detailed analyses of my operationalization of linguistic fluency, which I briefly sketch here.

A foremost identification concern is that respondents report fluency in a language based on their identification with groups with which the language is associated. Analyses in the Online Appendix indicate that this concern is at least not wholly warranted in this context. Online Appendix E examines the reasons respondents report learning languages, finding that individuals who learned a language for identity-based reasons are not more likely to report fluency in the language than those who report learning it for more utilitarian reasons. Online Appendix C explores the relationship between language and ethnic identity specifically. These analyses show that survey respondents are more likely to consider patrilineal descent as important for ethnic group membership than they are language, though language is also an important ethnic symbol in Gagauzia in particular.

Along similar lines, it is also possible that ties to Russia—in particular, spending an extended period of time in the country—could lead to increased proficiency in Russian and thereby stronger separatist sentiment. However, Online Appendix L presents analyses which indicate that there is little relationship between spending time in Russia and self-reported Russian fluency, which makes sense given the ample opportunities to develop fluency in the language in both Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia.

Moreover, Online Appendix D provides evidence that an adult's ability to develop fluency in a new language is likely constrained regardless of their identity. Specifically, survey data indicate that self-reported fluency in a language is rare among respondents who reported learning it as an adult. This result dovetails with psycholinguistic research on language acquisition, which holds that developing fluency in a new language is hard—if not impossible—for most adults (Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam Reference Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam2009; Hyltenstam and Abrahamsson Reference Hyltenstam and Abrahamsson2000).

I further validate this dichotomous indicator of linguistic fluency using a latent variable model (see Online Appendix N). The latent variable contains both self-reported fluency—the basis for the dichotomous indicators I use in the text—and responses to a variety of “can-do” questions (for example, “Can you talk about your day in language X?”).Footnote 12 These analyses serve two purposes. First, analysis of the parameters of the latent variable model reveals that the fluency measure I use in the text provides a valid measurement of this concept: the level of self-reported proficiency is highly discriminatory across levels of the latent concept (speaking capabilities), indicating a strong relationship with the can-do indicators of proficiency. Second, I rerun the analyses of support for separatism using the latent variable estimates. The analyses indicate that the dichotomous indicator is a conservative way to analyze the relationship between language and separatism, with the continuous latent measurement showing consistently stronger results in theoretically expected directions.Footnote 13

Finally, some of the effect of language on support for different separatist outcomes could be due to its relationship with media consumption. For example, Peisakhin and Rozenas (Reference Peisakhin and Rozenas2018) illustrate that access to Russian-language media increases support for pro-Russian politicians in Ukraine. I analyze the relationship between language, media, and support for separatism in Online Appendix M. The analyses indicate that respondents generally do not watch media in a language in which they are not fluent and that many respondents gravitate toward Russian-language media. However, the relationship between language-of-media-consumption and separatism is distinct from that between linguistic fluency and separatism.

Despite this substantial evidence that self-reported linguistic fluency is measuring the intended concept, an important caveat to the following analyses remains. Language and sovereignty have an iterative relationship: sovereignty at time t allows elites to increase the status of a peripheral language (Marquardt Reference Marquardt, Ayoob and Ismayilov2015), which, in turn, can reinforce peripheral sovereignty at time t + 1 (Gorenburg Reference Gorenburg2003; Laitin Reference Laitin1988). Territorial linguistic endowments—and thereby sovereignty—also influence an individual's linguistic calculations: it is rational for an individual to invest in teaching their child a language or trying to learn the language themselves only if others are doing the same (Laitin Reference Laitin1998). As a result, while these analyses provide insight into the relationship between language and separatism in these two regions in 2013, they are a snapshot of longer endogenous processes.

Observational Analyses of Support for Separatism

I use Bayesian ordinal probit regression analyses to observationally examine the relationship between linguistic fluency, ethnic identity, and support for separatism in both regions. Specifically, I regress individual-level support for regional independence—a quintessential separatist outcome—on linguistic and ethnic covariates, as well as standard demographic covariates. I use ordinal probit models due to the ordered-categorical outcome and a Bayesian approach for reasons detailed in the following section. While I do not pool the Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia data, the models are similar enough to discuss together.

Data and Model

I measure a respondent's support for regional independence using a five-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from “Fully disagree” to “Fully agree.”Footnote 14 I use the previously discussed dichotomous indicators of ethnic identity and linguistic fluency to operationalize these concepts.Footnote 15 I also control for demographic factors, including dichotomous indicators for respondent gender, higher education, and residents of urban settlements. I also control for respondent income and age (both log-transformed).Footnote 16

The Bayesian approach allows me to iteratively impute missing outcome values across draws from the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm based on a respondent's covariate values. Imputed responses will thus align with those of otherwise similar individuals who provided responses, albeit with uncertainty.Footnote 17

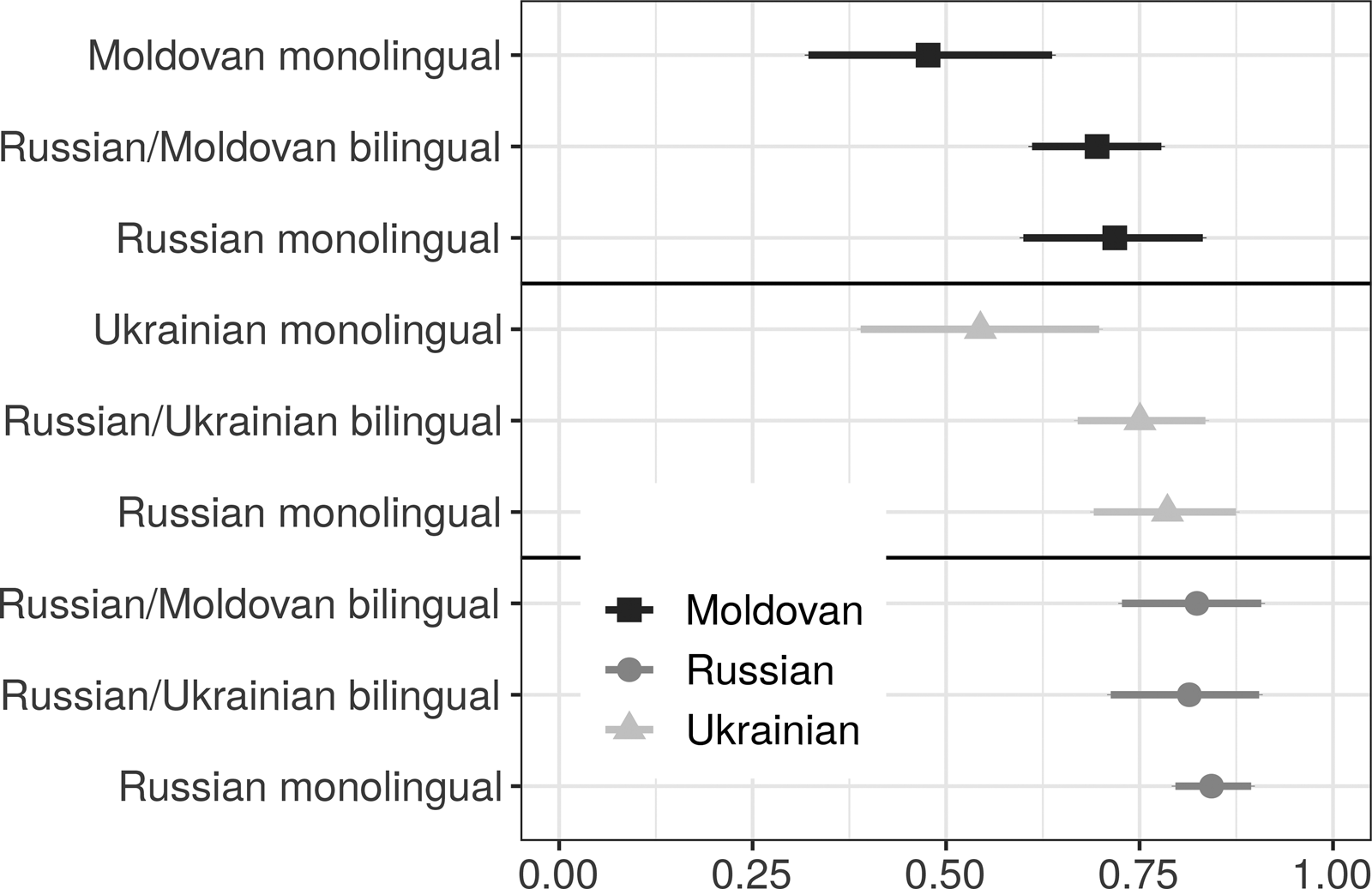

Support for Separatism in Pridnestrovie

Figure 2 reports the median posterior probability and 95 per cent credible region that a Pridnestrovian respondent supports Pridnestrovian independence given different combinations of linguistic repertoires and ethnic affiliations.Footnote 18 Given the relationship between ethnicity and language, I report only plausible ethnic and linguistic combinations on the vertical axis.Footnote 19 “Monolingual” represents an individual who is fluent in only one language, while “bilingual” represents an individual who is fluent in two languages.

Fig. 2. Posterior probability that Pridnestrovian respondents support Pridnestrovian independence.

Notes: Points represent the posterior median and horizontal lines the 95 per cent credible regions over 500,000 iterations of four MCMC chains. Shading represents estimates for different ethnic groups; rows show linguistic repertoires.

I order the ethnic–linguistic combinations first by ethnic group and then by linguistic combination; a lower position in the figure corresponds to a higher expected probability of supporting separatism. Given theoretical expectations from the ethnic politics literature, the central ethnic group (Moldovans) should have the lowest probability of supporting separatism and the main peripheral group (Russians) the highest; secondary peripheral groups (for example, Ukrainians) have more ambiguous expectations. In contrast, a linguistic theory of separatism holds that the most substantial variation in support for this outcome should occur within ethnic groups, with speakers of the peripheral language (Russian) most supportive of separatism and speakers of the central language (Moldovan) the least.

Figure 2 provides strong evidence in favor of linguistic explanations for separatism: proficiency in the main peripheral language (Russian) has the strongest relationship with support for separatism of all ethnic and linguistic characteristics. I estimate the probability that a monolingual Moldovan speaker (that is, a nonspeaker of Russian) supports separatism to be 0.24 less (95 per cent credible region [0.00–0.46]) than a monolingual Russian-speaking co-ethnic. There is a similar difference between monolingual Ukrainian and Russian-speaking Ukrainians: 0.24 (0.04–0.43). However, the analysis presents little evidence for a link between speaking the central language and support for separatism: bilingual Russian/Moldovan speakers tend to have similar political preferences as their monolingual Russian-speaking co-ethnics.Footnote 20

In line with ethnic theories of separatism, there is evidence members of the central ethnic group are less supportive of separatism than those of the main peripheral group: a monolingual Russian-speaking ethnic Moldovan has a probability of supporting separatism that is 0.12 less (0.00–0.26) than a linguistically equivalent Russian. However, the magnitude of the relationship between ethnicity and support for separatism is approximately half that of the relationship between proficiency in the peripheral language and support for separatism.

Support for Separatism in Gagauzia

Figure 3 presents results from the analysis of support for Gagauz independence. As with the Pridnestrovian results, I report the posterior probability that an individual with different ethnic identities and linguistic repertoires supports separatism. Ethnic Moldovans are the central ethnic group, and Moldovan is the central language, so monolingual Moldovan speakers are again at the top of the figure. Since Gagauz is the Gagauz ethnic language—and thus the most symbolically important peripheral language in line with ethnic theories of separatism—monolingual Gagauz speakers are placed at the bottom of the figure.

Fig. 3. Posterior probability that Gagauzia respondents support Gagauz independence.

Notes: Points represent the posterior median and horizontal lines the 95 per cent credible regions over 500,000 iterations of four MCMC chains. Shading represents estimates for different ethnic groups; rows show linguistic repertoires.

It should be noted that linguistic explanations of separatism would lead to a different ordering: Russian is the primary regional lingua franca in Gagauzia, as well as the language most closely linked to status and social mobility. As in Pridnestrovie, Russian proficiency should therefore have the strongest correlation with support for separatism.Footnote 21

The results are strongly in line with linguistic explanations of separatism: nonspeakers of the peripheral language (Russian) are the least supportive of this outcome. This result is starkest among monolingual Gagauz speakers. Contrary to the expectations of ethnic separatism, such a respondent has a posterior probability of supporting separatism that is 0.13 less than their monolingual Russian-speaking counterparts (95 per cent credible region [−0.02 to 0.26]).

Results for ethnic Moldovans corroborate this argument. As in Pridnestrovie, there is evidence that ethnic identity is salient for support for separatism in Gagauzia: a monolingual Russian-speaking ethnic Moldovan is 0.16 less likely (−0.00 to 0.33) to support separatism than their ethnic Gagauz linguistic counterpart. However, this difference is less than that between a monolingual Russian- and monolingual Moldovan-speaking ethnic Moldovan: a Moldovan speaker who does not speak the main peripheral language (Russian) has a probability of supporting separatism that is 0.22 less (0.06–0.38) than their monolingual Russian-speaking counterpart.

Experimental Analyses

Observational results provide strong evidence that linguistic abilities correlate with support for separatism in both Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia: respondents who lack fluency in the peripheral lingua franca are less likely to support separatism. However, they do not establish a causal link between linguistic proficiency and support for separatism. An ideal identification strategy would involve randomly assigning linguistic proficiency to respondents. Since such an experiment is impossible for financial, ethical, and temporal reasons, I deploy priming experiments to determine whether linguistic cues increase the salience of ethnicity—the most likely confounding variable in this analysis—or linguistic capabilities.

The rationale for the experiments is that individuals may not explicitly consider their language or ethnic identity when determining preferences over separatist outcomes. Priming individuals to consider their linguistic abilities should make these abilities salient, intensifying their link to political preferences.

Linguistic explanations of separatism yield clear expectations for these analyses: linguistically primed individuals who either speak the central language (Moldovan) or do not speak the main peripheral language (Russian) should be less supportive of separatism than individuals who are not primed to consider the relevant languages. On the other hand, if the importance of language lies in its symbolic relationship with ethnicity, then the primes should intensify the relationship between ethnic identity and support for separatism, for example, linguistically primed ethnic Moldovans should be less supportive of separatism, regardless of their linguistic repertoire.

Experimental Design

For the experiment, survey software randomly assigned respondents to one of four conditions: a control, in which the respondent was presented with no linguistic prime; or one of three linguistic primes related to Moldovan, Russian, or Ukrainian/Gagauz fluency (Ukrainian in Pridnestrovie; Gagauz in Gagauzia). The primes involve asking the respondent “Do you speak X fluently?” with X corresponding to one of the aforementioned languages.Footnote 22 I henceforth refer to these treatments as T Moldovan, T Russian, and T Ukrainian/Gagauz. The primes are relatively innocuous to avoid contamination of the results by introducing additional content into the question: the results would likely be more pronounced had the prime packed more political or cultural punch (Pérez Reference Pérez2015). Following the prime, enumerators asked respondents their preferred outcome for region–Moldova political relations, with the options of their region becoming: (1) part of Moldova without autonomy; (2) part of Moldova with autonomy; (3) part of a confederation with Moldova; or (4) a separate state.

Bayesian Hierarchical Analyses

I use Bayesian hierarchical models to analyze the experimental data because theory yields a strong a priori assumption of heterogenous treatment effects: the primes should intensify either linguistic or ethnic preferences with regard to separatism, leading individuals with different linguistic and ethnic backgrounds to respond differently to them.Footnote 23 Moreover, there are multiple potential interactions between the treatments and linguistic and ethnic variables. For example, T Russian could remind monolingual Moldovan speakers of the Russian language's privileged status in Pridnestrovie, reducing their support for separatism. Explicit modeling of these interactions—and reporting these results—is therefore necessary (Imai and Ratkovic Reference Imai and Ratkovic2013). The Bayesian hierarchical modeling approach I use here reduces the risk of false positives by shrinking the conditional effect of each covariate based on an underlying distribution (Feller and Gelman Reference Feller, Gelman, Scott and Kosslyn2014).

The Model

I use an ordinal probit model to assess the relationship between language, ethnicity, and support for separatism. The highest level of the outcome represents support for separate statehood; the lowest level represents support for full integration with Moldova. I hierarchically cluster experimental condition intercepts and coefficients for the three linguistic covariates (Not fluent in Russian, Fluent in Moldovan, and Fluent in Ukrainian/Gagauz) and ethnic covariates. Since there is no theoretical reason to believe that the relationship between the demographic controls and support for separatism varies across treatments, I model their coefficients as treatment invariant.

Pridnestrovie Experimental Results

Figure 4 presents results from the Pridnestrovie priming experiment. It reports the posterior probability that respondents with different ethnic and linguistic characteristics would support Pridnestrovian independence, across experimental outcomes. The cells are divided first by the respondent's linguistic repertoire, then by experimental condition; the bottom row of each ethnic–linguistic repertoire represents an individual in the control condition. I focus on ethnic Russians and Moldovans since these groups contain the ethnic and linguistic combinations with the clearest empirical expectations.Footnote 24 Specifically, if the salience of language lies in its relationship to linguistic capabilities—as opposed to ethnic identity—T Moldovan should decrease support for separatism among Moldovan speakers, while T Russian should increase support for separatism among Russian speakers. On the other hand, if language is primarily important as a symbol of ethnic identity, then T Moldovan should decrease support for separatism among ethnic Moldovans, while T Russian should increase support for separatism among ethnic Russians, regardless of their linguistic repertoires.

Fig. 4. Posterior probability of supporting Pridnestrovian independence across experimental conditions by ethnic group.

Notes: Points represent the posterior median and horizontal lines the 95 per cent credible regions over 500,000 iterations of four MCMC chains. Shading represents estimates for different linguistic repertoires; rows show experimental conditions. Vertical lines represent the posterior median for an individual of a given linguistic repertoire in the control condition.

The clearest experimental result regards T Moldovan, which consistently decreases the posterior probability that a speaker of the central language (Moldovan) would support separatism, in line with linguistic explanations for separatism. For example, the median posterior difference in the probability that an ethnic Moldovan (bottom cell) who is bilingual in Russian and Moldovan would support Pridnestrovian independence in the T Moldovan versus control condition is −0.30 (95 per cent credible region [−0.52 to −0.05]); for a monolingual Moldovan speaker, the difference is −0.26, albeit with high uncertainty due to the small sample size of monolingual Moldovan speakers. Similar priming effects are visible across ethnic groups: a bilingual Russian/Moldovan speaking Russian (top cell) is estimated to be 0.36 less likely (−0.01 to 0.69) to support separatism in T Moldovan versus the control condition.

The fact that Moldovan proficiency shows a weaker relationship with support for separatism in the observational analyses is perhaps evidence that the Moldovan language is less salient to Pridnestrovians than the Russian language. While abilities (or lack thereof) in the main peripheral language is a constant factor in everyday life, the political importance of Moldovan proficiency may only be clear when respondents are thus reminded. This interpretation dovetails with the lack of evidence of a linguistic treatment effect for the peripheral language prime (T Russian): since Russian is already salient, the prime is redundant.

The other important finding from the experiment is the null results for ethnic treatment effects. If linguistic primes were priming ethnic identity, then T Moldovan should reduce the posterior probability that all Moldovans support separatism. Instead, it only affects Moldovan speakers: if anything, this treatment increases the probability that monolingual Russian-speaking Moldovans support independence. Similarly, T Russian has little apparent effect on ethnic Russians (the main peripheral group), regardless of their linguistic repertoire.

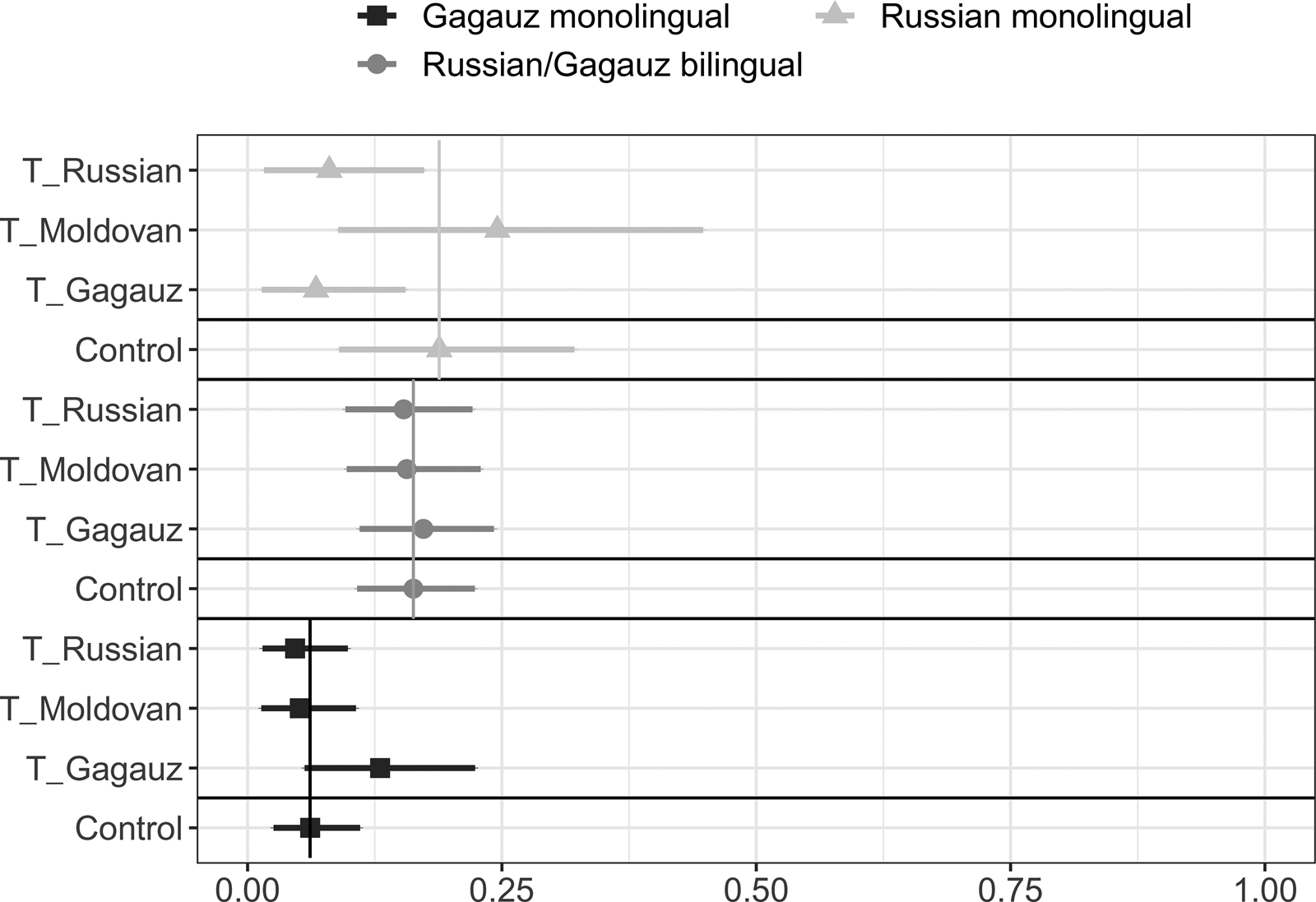

Gagauzia Experimental Results

Figure 5 shows results from the survey experiment in Gagauzia, focusing on results for ethnic Gagauz with different linguistic repertoires (for results for other ethnic groups, see Online Appendix J). Given the small number of Gagauz who are fluent in Moldovan in the survey, these results can only speak to the degree to which primes affect the relationship between separatism and different peripheral languages: Russian, the peripheral lingua franca, and Gagauz, the language most closely linked to peripheral ethnic identity. As with Pridnestrovie, the expectation is that T Russian intensifies support for separatism among Russian speakers. Expectations for Gagauz are ambiguous. Since the Gagauz language is closely linked to Gagauz sovereignty, T Gagauz should increase Gagauz speakers' support for separatism. However, as in the observational results, the Russian language's primary role in Gagauzia may mitigate this relationship.

Fig. 5. Posterior probability that ethnic Gagauz support regional independence across experimental conditions.

Notes: Points represent the posterior median and horizontal lines the 95 per cent credible regions over 500,000 iterations of four MCMC chains. Shading represents estimates for different linguistic repertoires; rows show experimental conditions. Vertical lines represent the posterior median for an individual of a given linguistic repertoire in the control condition.

The results indicate that the interplay between Gagauz fluency and support for separatism is more complicated than the observational results suggest. Most prominently, there is evidence that T Gagauz increases support for separatism among monolingual Gagauz speakers: the median posterior difference in the probability that a monolingual Gagauz speaker supports Gagauz independence between the control and T Gagauz conditions is 0.07 (95 per cent credible region [−0.02 to 0.17]).Footnote 25 While the credible region overlaps 0, this result provides some evidence that increasing the salience of the language can increase the probability that its speakers support separatism. Indeed, the posterior probability that a monolingual Gagauz speaker supports separatism in T Gagauz is similar to the probability that a bilingual Gagauz/Russian speaker or monolingual Russian speaker supports separatism in the control condition (0.13, 0.16, and 0.19, respectively—all estimates well within uncertainty intervals).

Nevertheless, the effect of T Gagauz is not consistent among ethnic Gagauz with different linguistic repertoires. This result indicates that the priming effect is linguistic, not ethnic (that is, the prime increases the salience of the Gagauz language, not ethnic identity). The prime has no clear effect on the posterior probability that a bilingual Russian/Gagauz speaker would support separatism and actually has a negative effect on support for separatism among monolingual Russian-speaking Gagauz (a difference of −0.12 [−0.26 to 0.01] relative to the control condition).

Contrary to theoretical expectations, T Russian does not increase support for separatism among Russian speakers. It has no clear effect on support for separatism among bilingual Russian/Gagauz speakers and, if anything, a negative effect on monolingual Russian-speaking Gagauz (−0.10 [−0.25 to 0.03] relative to the control condition).

As a final comment, it should be noted that the support of bilingual Gagauz/Russian speakers for separatism is consistently strong across experimental conditions.Footnote 26 In conjunction with (1) the evidence that individuals with this repertoire tend to be the most supportive of separatism relative to their monolingual Russian and Gagauz peers, (2) the counterintuitive experimental effects of T Gagauz and T Russian on monolingual Russian speakers, and (3) the positive effect of T Gagauz on support for separatism among monolingual Gagauz speakers, this result is perhaps evidence that both languages have an important role in support for Gagauz sovereignty, though their exact role remains contentious.

Conclusion

Language can provide a strong explanation for separatist sentiment, even in the absence of a link to ethnic identity. Speakers of a peripheral language have a strong incentive to support regional sovereignty, as doing so preserves the status of their language and thus their social mobility. In contrast, speakers of the language of the central state have an incentive to oppose separatism, as they will accrue greater benefits from integration with the state where their language enjoys a high status. Language can also cut across ethnic divides, unifying a multiethnic peripheral population in support of separatism. This argument runs counter to ethnic theories of separatism, which hold that ethnic identity determines an individual's support for separatism and that language is merely a proxy for ethnicity.

Results from observational analyses of Pridnestrovie and Gagauzia provide strong evidence supporting the linguistic argument. In both regions, individuals fluent in a peripheral lingua franca, Russian, are more supportive of separatist outcomes than individuals who are not fluent. This result holds across ethnic groups. Moreover, results from Gagauzia indicate that the effect of language is due not necessarily to its connection with ethnic identity, but rather to its role in social mobility and day-to-day life: monolingual speakers of a peripheral ethnic language (Gagauz) are less supportive of separatism than bilingual Gagauz/Russian speakers and monolingual Russian speakers with similar ethnic backgrounds.

Experimental results provide further evidence that the role of language in determining support for separatism is a function of linguistic proficiency, not ethnic identity. In Pridnestrovie, priming individuals to consider their proficiency in the Moldovan language decreases support for separatism among Moldovan speakers, regardless of their ethnic identification. In Gagauzia, priming for Gagauz proficiency increases support for separatism among monolingual Gagauz speakers, while decreasing support for separatism among monolingual Russian speakers. Given the prevalence of Russian in Gagauzia, this finding indicates that respondents require priming to make the Gagauz language salient for separatism. In all cases, there is little evidence in either region that the linguistic primes affect the relationship between ethnic identity and support for separatism.

These results have important implications for the study of identity and separatism. First, the consistent presence of linguistic appeals in separatist conflicts worldwide indicates that the linguistic dynamics at play in Gagauzia and Pridnestrovie may be of vital importance to understanding separatism elsewhere. Scholars should therefore not assume that language is a proxy for ethnic identity in cases of separatism and conflict, but consider linguistic differences themselves as having an important relationship with separatism. Second, in line with Liu (Reference Liu2015), scholars should consider the political relevance of language in their analyses. Politically relevant languages may not be those of an ethnic group; a language's political relevance may instead come from its importance to everyday life and social mobility in both the periphery and the central state. Third, this article focuses on the political importance of linguistic fluency, which has a clear theoretical link to preferences over separatist outcomes. However, as Onuch and Hale (Reference Onuch and Hale2018) note, different aspects of language have different implications for political preferences. Future research would do well to both theoretically and empirically probe how different aspects of language—for example, not only identification, but also levels and forms of proficiency, as well as accents—can influence preferences over separatism and other political outcomes of interest.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000533.

Data Availability Statement

Replication data files are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/TOJZPZ

Acknowledgments

I thank Yoshiko Herrera, Scott Gehlbach, Alexander Tahk, Rikhil Bhavnani, and Ted Gerber for their essential contributions to this project. I also thank Kristen Kao, John Ahlquist, Dominique Arel, Nicholas Barnes, Ruth Carlitz, Hannah Chapman, Matthew Ciscel, Barry Driscoll, Evgeny Finkel, Adam Harris, Bradley Jones, Patrick Kearney, David Laitin, Staffan Lindberg, Anna Lührmann, Ellen Lust, Israel Marques II, Juraj Medzihorsky, Rick Morgan, Marc Ratkovic, and Steven Wilson for their insights at different stages of this project. The survey benefited greatly from consultations with the staff of IMAS-Inc in Chisinau, especially Doru Petruţi, Veronica Ateş, Elena Petruţi, and Cristina Tudosov. Earlier drafts were presented at the 2015 Association for the Study of Nationalities World Convention and the 2016 UW–Madison Comparative Politics Colloquium, as well as in seminars at the University of Gothenburg and the 2019 New Voices on Russia Seminar Series at George Washington University.

Financial Support

I acknowledge research support from: the National Science Foundation, Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Award No. 1160375; the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Fellowship; Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, Grant M13-0559:1; the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Grant 2013.0166; the Swedish Research Council, Grant 439-2014-38; and the HSE University Basic Research Program. Statistical analyses used computational resources provided by the High Performance Computing section and the Swedish National Infrastructure for Computing (SNIC) at the National Supercomputer Centre in Sweden, SNIC 2017/1-406.

Competing Interests

None.

Ethical Standards

I conducted research according to protocols 2012–1016 and SE-2011-0189 of the University of Wisconsin–Madison Education and Social/Behavioral Science Institutional Review Board.