Introduction

The end of the last Ice Age in Britain (c. 11500 BP) created major disruption to the biosphere. Open habitats were succeeded by more wooded landscapes, and changes occurred to the fauna following the abrupt disappearance of typical glacial herd species, such as reindeer and horse (Conneller & Higham Reference Conneller, Higham, Ashton and Harris2015). Understanding the impact of these changes on humans and how quickly they were able to adapt may soon become clearer, due to recent discoveries in the Colne Valley on the western edge of Greater London, north of the River Thames. An exceptionally well-preserved open-air site was discovered in 2014 as part of a wider project of archaeological investigation and excavation carried out by Wessex Archaeology (2015), on behalf of CEMEX UK. The site, at Kingsmead Quarry in Horton, is unusual because it has good organic preservation and, in addition to worked flint artefacts, it has yielded groups of articulated horse bone. The extreme rarity of such sites of this period in Britain makes this discovery especially significant and re-emphasises the potential importance of the Colne Valley (Lacaille Reference Lacaille1963; Lewis Reference Lewis and Rackham2011; Morgi et al. Reference Morgi, Schreve, White, Hey, Garwood, Robinson, Barclay and Bradley2011).

The site

Kingsmead Quarry is situated on the wide floodplain of the River Colne, 1km south-east of the village of Horton in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead, Berkshire. Today it is located in a meander of the River Thames, 1.5km west and 3km north of the present course of the river, but less than 800m from a former major channel that may have been active at the time. Investigations within the quarry have revealed a network of earlier, south-flowing, river channels feeding into the former major channel. The site is bounded on its eastern edge by the Colne Brook, a tributary of the River Colne (Figure 1). The underlying geology consists of floodplain gravels overlain by brickearth, which varies in thickness across the site.

Figure 1. Pre-excavation view of Kingsmead Quarry Horton LUP site; the bags mark the position of surface material comprised of bones and flint.

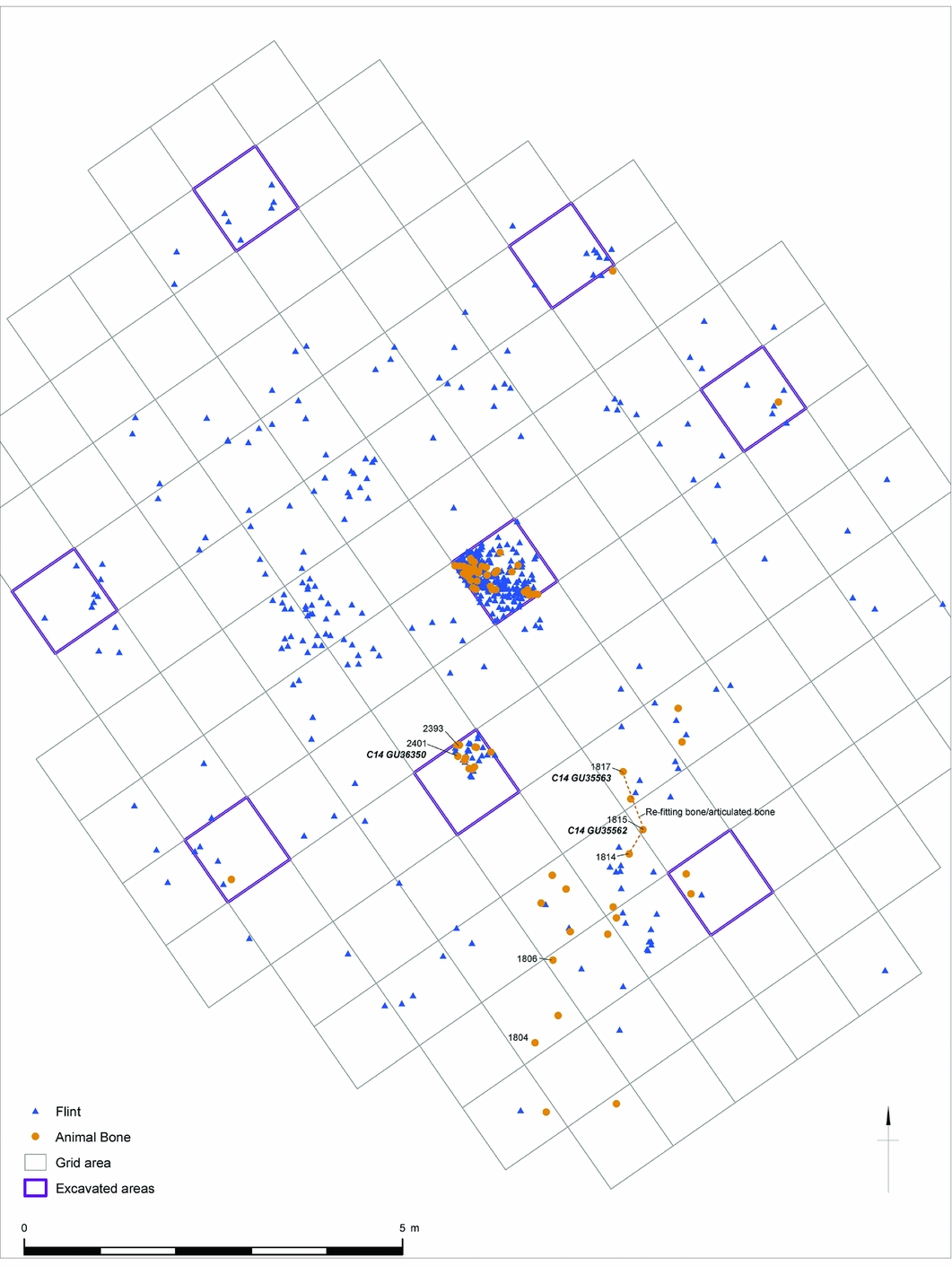

The site was discovered during the removal of topsoil in advance of the excavation of mainly later prehistoric and Romano-British settlement remains and palaeochannel deposits already known in the vicinity (Chaffey et al. forthcoming). Preparatory work revealed an extensive surface scatter of flint and bone occupying a slightly raised gravel bar between palaeochannels, and covering an area of 150m2. The scatter was then systematically mapped and collected (Figure 2). It included unabraded flint artefacts (Figures 3–4) and complete and fragmentary animal bone, which, in one instance, comprised a cluster of articulated horse ankle bones in their original anatomical position (Figure 5). Following this discovery, and to inform the planning process further, eight 1 × 1m test pits were investigated according to standard methods for excavating sites of this character (Lewis Reference Lewis and Rackham2011). Each test pit was dug in 50mm spits, and finds greater than 10mm in maximum dimension were recorded using 3D GPS. Targeted sampling for wet sieving was also undertaken to assess the preservation of environmental remains and examine the presence of microdebitage. The excavations confirmed that the flint and bone distribution continued to some depth above the gravel deposits, with densities of up to 1200 artefacts per square metre, including microdebitage. The freshness of the flint leaves little doubt that most of the assemblage is in situ, probably only slightly affected by gentle overbank flooding processes and some vertical movement of finds. As bone surface preservation is variable, it is probable that traces of butchery will not survive. Provisional examination, however, confirms the presence of fresh breakage of bone for marrow extraction. The presence of nearby hearths—which again would be very rare for this period in Britain—is suggested by quantities of burnt bone and calcined flint. There is also nothing in the flint assemblage to imply major intrusion of later artefacts. It is estimated that the scatter could hold a minimum of 19000 fragments of flint and bone, and possibly as many as 43000, depending on the actual extent.

Figure 2. Distribution of all recorded flint and animal bone, and the location of AMS 14C samples and the articulating horse bone.

Figure 3. Opposed platform blade cores.

Figure 4. Selection of flint artefacts from the site: end-scraper 20179; blades including refits 2077 and 2291; snapped trapezoidal microlith 2160.

Figure 5. Articulated horse bones (ON 1814, 1815 and 1817).

In terms of dating the assemblage, AMS radiocarbon assays have revealed that although many of the bones have poor collagen preservation, a single date on a horse tooth has yielded an age of (SUERC-57714) 9920±39 BP (11410–11230 cal BP at 95% confidence). The dating is consistent with another date on a partial aurochs skeleton (SUERC-62321) 9946±53 BP (11620–11230 cal BP at 95% confidence) from adjacent channel deposits, and a third date of (UBA-34734) 9977±55 BP (11720–11240 cal BP at 95% confidence) (OxCal v4.2.4; Bronk Ramsey & Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013) on waterlogged Carex sp. seeds from the base of the peat within the channel. All three dates fit with a final Later Upper Palaeolithic age for activity. From a broader perspective, the presence of this site emphasises the importance of the Colne Valley as a focus of Late Glacial settlement in Britain. Other significant open-air locations have already been excavated at Three Ways Wharf, Uxbridge (Lewis Reference Lewis and Rackham2011), and Church Lammas (Jones Reference Jones2013), both just a few kilometres from Kingsmead Quarry.

At Three Ways Wharf, a nationally important undisturbed sequence of sediments containing four artefact scatters and associated faunal material were recorded. In one of the scatters, long blades were found associated with butchered horse remains that have been dated to 10270±100 BP (OxA-1778: 12420–11620 cal BP at 95% confidence) and 10060±45 BP (OxA-18702: 11820–11330 cal BP at 95% confidence using ultrafiltration) (scatter A). Another dated scatter contained a very different flint assemblage with red deer (but no horse remains), and with an age of 9280±110 BP (OxA-5557: 10750–10220 cal BP at 95% confidence) (scatter C). The significance of the Kingsmead Quarry site is that it falls chronologically within these two dates and provides rare evidence of the development from the Late Glacial (Later Upper Palaeolithic) to the early post-glacial (Mesolithic) periods.

Conclusions

The fieldwork at Kingsmead Quarry has confirmed the survival of a rare example of a site occupied by some of the last Ice Age hunter-gatherers in Britain. Its significance is further enhanced by the pristine nature of the archaeological finds and the very high potential for preserved environmental evidence, including plant and animal remains. Such sites dating to the very end of the last Ice Age are exceptionally rare in Britain (Barton Reference Barton2010). The existence of at least two other sites in the same valley offers enormous possibilities for finding further locations and buried landscapes of this age, which now lie relatively close to the surface. The site is currently protected, but any long-term preservation remains in doubt, especially concerning the fragility of the surviving bone. Post-excavation analysis is now underway to produce a more detailed study of the assemblage and to assess and inform the next stages of the project. The results will illuminate a key transitional phase of the Later Upper Palaeolithic against the backdrop of a fast-disappearing Late Glacial world.

Acknowledgements

Wessex Archaeology is grateful to CEMEX UK, specifically Andy Scott, for commissioning the work through their consultant Adrian Havercroft of the Guildhouse Consultancy, who is also thanked for his help and support. Wessex Archaeology would also like to thank Fiona MacDonald and Roland Smith of Berkshire Archaeology (Reading Borough Council) for their help and advice. Karen Nichols is thanked for her help with the plates and figures.