Anorexia nervosa is often a chronic, severe disorder in which morbidity and mortality are high. After 20 years, as many as 20% of clinical series have died (Reference PattonPatton, 1988) and another 20% have experienced poor outcome (Reference Tolstrup, Brinch and IsagerTolstrup et al, 1985).

At presentation, the majority of patients with anorexia nervosa are ambivalent about treatment. Few wish to gain weight despite life-threatening emaciation. On the whole, these patients do not share the goals of treatment considered appropriate by those involved in their care. Furthermore, the psychological symptoms of starvation (poor concentration, preoccupation with weight and shape and depressed mood; Reference Keys, Brozak and HenshallKeys et al, 1950), significantly affect their capacity to engage in the therapeutic process. These are the factors that explain why this patient group are considered difficult to work with and resistant to treatment. This presents an interesting challenge: the severity of the disorder dictates that we must intervene, but how do we do so successfully if the sufferer does not, or cannot, accept our help?

We aim to provide an overview of the management of medical and psychological aspects of anorexia nervosa with an emphasis on managing resistance and motivating change.

Treatment settings

Within current practice in the UK, there is an attempt to match intensity of treatment of anorexia nervosa with severity of need, and it is no longer the case that admission is deemed essential for successful treatment. Indeed, there is some evidence that relative to in-patient care, out-patient treatment may yield greater compliance and as good an outcome of treatment (Reference Crisp, Norton and GowersCrisp et al, 1991). In-patient care is therefore reserved for those with the greatest need (see Box 1). When admission is appropriate because of medical reasons, but is declined by the patient, it may be necessary to use the Mental Health Act 1983. Food is considered treatment in terms of the Act (Mental Health Act Commission, 1997). In such a case, it is important that the patient is treated in a unit that has the requisite skills. Rarely can a general psychiatric or general medical unit give the intensity of care that is needed (Reference Treasure and RamsayTreasure & Ramsay, 1997). Indeed, referral to specialist eating disorder services is recommended for all patients with anorexia nervosa and certainly for those with poor prognostic features (see Box 2).

Box 1. Clinical and psychiatric grounds for admission

Medical

BMI <13.5 kg/m2 (or rapid rate of fall)

Syncope

Proximal myopathy (patient unable to stand from squatting without using arms)

Hypoglycaemia

Severe electrolyte imbalance

Petechial rash and platelet suppression

Psychiatric

Risk of suicide

Chronicity >5 years

Comorbid impulsive behaviour

Intolerable family or social situation

Failure of out-patient treatment

Box 2. Poor prognostic features

Long duration, resistant to treatment

Lower minimum BMI

Older age of onset

Personality difficulties

Social difficulties

Relationship with family poor (for review see Reference Steinhausen, Rauss-Mason and SeidelSteinhausen et al, 1991)

Specialist in-patient care

Strict behavioural regimes are no longer considered appropriate for the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Rather, a skilled multi-disciplinary team can establish collaborative working relationships with patients, utilising peer pressure within the group setting to motivate and support patients through re-feeding. In such settings, forced feeding is rarely necessary. Psychological issues are addressed in individual therapy, group and family work – the ward environment providing safety and containment.

Monitoring weight

Ideally, patients with anorexia nervosa should be weighed at every session and the weight plotted on a graph indicating weight over time. Body mass index (BMI) is the ratio of weight in kilograms over height in metres squared, the healthy range being 20–25 kg/m2. It is BMI and rate of change in weight, rather than weight per se, that guide management.

Josie, a 22-year-old with anorexia nervosa of the binge/purge subtype, presented with a BMI of 15.5 kg/m2. Her electrolytes and blood screening were normal and she had reasonable circulation: pulse rate 60, blood pressure 110/70, with no postural drop or oedema. There were no medical concerns indicating need for admission. Although she had a difficult relationship with her family and boyfriend, they remained supportive. Out-patient treatment was therefore appropriate. However, as this was now her fifth year of illness, failure of progress in therapy would lead to review for admission.

However difficult sessions might seem, if the patient is gaining weight, therapy is working. Conversely, static or falling weight indicates a need to review management and consider referral for specialist care. Additionally, changes in weight provide useful insight into the progress of treatment and the therapeutic relationship.

During the early stages of treatment, Josie appeared attentive and well-motivated to change her bingeing and purging behaviours. However, she was resistant to any suggestion that she should gain weight, expressing the belief that she was fat. Her weight remained static during the first four sessions, consistent with her ambivalence about change. Later in treatment, during a period of slow but steady weight gain, a decrease in the rate of gain coincided with the therapist cancelling a session, indicating that the break had been difficult for Josie, perhaps leaving her feeling exposed, vulnerable and angry with the therapist. By expressing and validating these feelings in the subsequent sessions, the therapist was able to restore the therapeutic alliance and weight gain improved.

Early sessions and engagement

Stages of change and the decisional balance

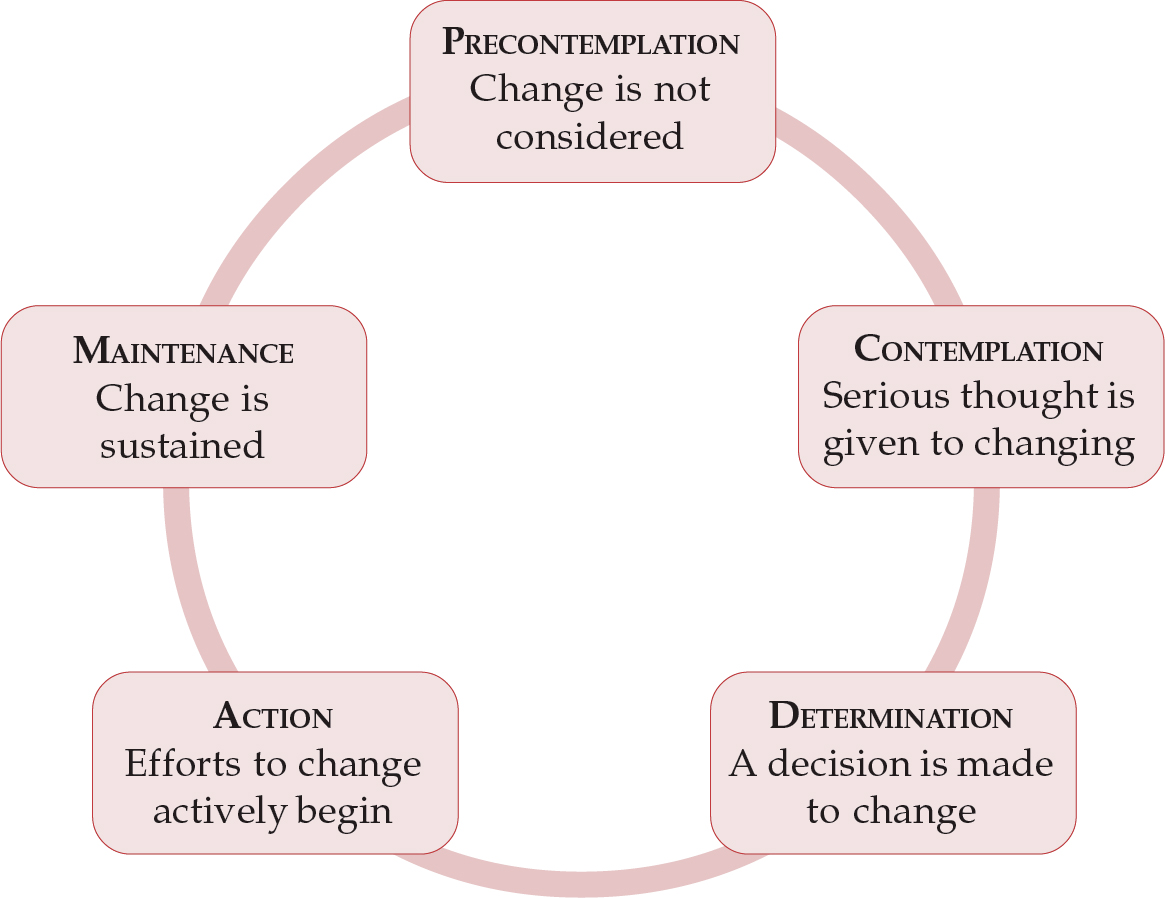

Prochaska & DiClemente's (1992) well-known transtheoretical model for change can be usefully applied to anorexia nervosa. The model represents change as a process revolving through five stages: precontemplation, contemplation, determination, action and maintenance (see Fig. 1). Movement through the stages may be both toward and away from active change, and many cycles may be necessary before change is maintained.

At presentation, only about 50% of patients with anorexia nervosa are in action, the remainder being in the stages of precontemplation or contemplation (Reference Blake, Turnbull and TreasureBlake et al, 1997). Recommendations for active behaviour change early in treatment may therefore be inappropriate to a patient's stage of change, and may result in resistance. Treatment strategies must be matched to a patient's readiness for change. Accordingly, it is helpful to facilitate the move from contemplation to determination during the process of assessment and engagement by exploring with a patient her concerns about change or the status quo. Homework tasks, such as writing letters to ‘anorexia my friend’ and ‘anorexia my enemy’ are helpful tools for eliciting these pros and cons in a collaborative way (Reference Serpell, Treasure and TeasdaleSerpell et al, 1999).

In her letter to anorexia, her friend, Josie expressed gratitude for feeling looked after and safe with anorexia in her life. In the letter to anorexia the enemy, she described bitterly the changes that she had noticed in her life. She wrote that since losing weight she had become very sensitive to the cold, was always tired, had great difficulty concentrating on her work and was arguing constantly with her parents, with whom she was living. Although she had considered moving in with her boyfriend, she had been unable to do so, feeling that the anorexia had come between them and caused difficulties in their sexual relationship.

Similarly, the pros and cons for change can be explored by asking the patient to imagine what her life would be like 10 years on if she still had the anorexia, and if she had recovered.

Josie was asked to write a letter to a friend 10 years on describing her life as she imagined it might be. With anorexia still in her life, she imagined that she would still be living at home, unmarried, childless and no longer able to work. The physical consequences of her illness were profound and although she loved horse riding, she had long since given up, lacking the strength to continue. The life she described was shrunken and bleak. In contrast, without the anorexia, she saw herself happily married with a successful career in the travel industry. Having spent many years enjoying the travel opportunities that were a perk of her trade, she now had a young child and was expecting her second. She had an active social life and spent what free time she had riding at a local stables.

These pros and cons for sticking with the anorexia or for change make up the ‘decisional balance’. Research suggests that rather than attempting to denigrate reasons for not changing, enhancing the pros for change is more effective in shifting the decisional balance towards change. The key here is to avoid frustrations, arguments and confrontations about diagnosis and unshared goals and beliefs, and instead to foster an empathic relationship in which the difficulties inherent in changing are acknowledged.

Motivational enhancement

The motivational style of interviewing described by Miller & Rollnick (1991) facilitates work in people in the precontemplation and contemplation stages of change. Reflective listening and empathic understanding are used to enhance discrepancy between beliefs and to motivate change. It is important that sufficient time and attention is given to the way in which anorexia nervosa is of benefit, and not simply to how costly it is. A judgemental and argumentative flavour to reflections is avoided by using ‘and’ rather than ‘but’ to link ideas. Critically, when reflecting discrepant concerns, motivation is enhanced if statements promoting change are made last. For example:

“Josie, you are sure that you do not wish to gain weight and you are finding it extremely difficult to manage your work because you cannot concentrate as you used to and are always so dreadfully tired.”

“You feel safe and looked after by anorexia and you feel that your relationship with your boyfriend has become distant and difficult to sustain.”

“If you stick with the anorexia, you see a bleak future ahead and recovery seems to offer the fulfilment of marriage, children and a successful and enjoyable career.”

Imparting information

Psychoeducation, with the correction of mistaken assumptions and clarification of negative issues – such as the profound psychological, social and medical consequences of starvation – are key components of treatment.

It is best to avoid imposing information, as patients will be likely to experience this as nagging. Rather, relevant information can be offered in response to the patient's expressions of concern or interest. The doctor should act as a tutor or advisor, rather than a commanding officer. This type of approach is experienced as both respectful and intriguing. A motivational feedback represents one particular way of imparting relevant information and enhancing motivation. Information from medical assessment and investigation (see Box 3) can be used in this way. It is important, however, that the medical feedback is not so horrific, shocking or hopeless that it is blocked off. The majority of medical complications reverse with weight gain and the possibility of hope and benefit from change should be maintained.

Box 3. Common medical complications

Acute complications associated with malnutrition and purging

Electrolyte disturbance; dehydration; renal failure

Anaemia; leucopenia

Clotting abnormalities

Cardiac arrhythmia; bradycardia; hypotension; peripheral cyanosis; oedema

Delayed gastric emptying; gastric dilatation; constipation; ileus

Peptic ulceration; oesophageal tears; pancreatitis

Amenorrhea

Infection; hypothermia

Fits; faints; blackouts

Additional complications arising with chronicity

Chronic renal failure

Reduced fertility

Osteoporosis → fractures, pain; kyphosis; loss of height

Dental erosion; parotid gland enlargement

Josie's bone scan revealed lower bone density than expected for her age. Although she had heard of osteoporosis, she had thought it was a disease affecting only older women. She wanted to know more about the possible causes and consequences and these were discussed with her (see below). She was so concerned that this might prevent her from horse riding now and in the future that she decided to take calcium supplements and to think about maintaining a slightly higher weight.

The motivational model

These various techniques constitute the core skills of the motivational model (Reference Treasure and WardTreasure & Ward, 1997a ), that is, the use of motivational interviewing to explore the decisional balance and to exchange information in such a way as to enhance motivation for active change. The motivational model should be used throughout the treatment process. During engagement, the model is invaluable in negotiating the balance of power and control between the patient and therapist. It helps foster a collaborative therapeutic alliance, essential to a successful therapy. This is especially pertinent in the context of compulsory admission and treatment. However entrenched the anorexia, some expression of concern can usually be elicited. In extremis, this may be limited simply to the patient's resentment of compulsory admission. In the initial phase of treatment, concerns may be predominantly of a somatic nature. However, the patient's experience of being listened to and understood may engender curiosity about her profound subjective experiences. Once trust has developed in the therapeutic relationship, the way is paved for exploration of areas of emotional pain and difficulty.

Formulation

A thorough formulation of the case is an essential task before expecting the patient to move into action. This can be more difficult in anorexia nervosa than other forms of psychiatric pathology, as these patients avoid dwelling on painful life events or autobiographical memories (Reference Troop, Holbrey and TrowlerTroop et al, 1995). Attention is given to the intra- and interpersonal domains as well as symptoms. The emphasis is always upon making links between painful and difficult feelings about the self; attachment style and relationships in early life; and current patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving that maintain symptoms and difficulties. Thus, an eclectic formulation drawing from both cognitive–behavioural and analytical models of understanding is desirable. The dominance of each model can be adjusted to suit the needs and style of thinking of the individual patient.

Psychoanalytic formulations of anorexia nervosa frequently conceptualise it as a disorder of self-experience, in which lack of attunement and response to the patient's subjective experience early in life result in a limited capacity to experience and tolerate emotions, and a disordered sense of self (Reference De Groot and RodinDeGroot & Rodin, 1998).

The initial cognitive–behavioural formulations focused merely upon issues of weight and shape. These have been elaborated to include control (Reference Fairburn, Shafran and CooperFairburn et al, 1999) or to core inter- and intrapersonal schema (Wolff & Serpel, 1998).

A family session can provide very useful material for the formulation and may expose patterns of attachment and interpersonal relationships that may be more difficult to recognise in individual sessions.

It was clear from Josie's first family session that the expression of angry or painful feelings was difficult for all members of the family. Any attempts to do so were met by smiling placation from her mother, which Josie later described as ‘weak and pathetic’. In contrast, her father was experienced as angry and disapproving. Throughout the session, Josie lowered her head and said little, explaining afterward that she had feared to speak her mind lest she upset her father.

These experiences describe a controlling and conditional father with whom Josie feels crushed and strives to please. One might predict that this pattern of relating will recur in the therapeutic relationship, highlighting the need for the therapist to avoid the controlling, conditional role.

We have found it useful to share a formulation with the patient, in the style of the cognitive–analytical therapy (CAT) reformulation letter, in which it is offered as a ‘hypothesis’, and so is carefully worded: “It seems to me that your experience of early life may have been…”; “It perhaps felt as if…”; “Maybe this led you to believe…”; “I imagine that…”. The aim is to collaborate in developing an understanding and an emotional language that is shared. The patient's own words and descriptions are therefore used whenever possible and after reading the letter to her, she is invited to comment on it and to suggest appropriate changes.

The goals of therapy should be clearly laid out, but beware of jumping to a premature focus. The degree to which goals are shared must be discussed and negotiated. Unshared goals are an obstacle to the therapeutic alliance, but so too is collusion with inappropriate goals. This is therefore an issue that is returned to again and again during the course of therapy.

Psychotherapy models

There are very few randomised controlled treatment studies of anorexia nervosa and most are very small and unrepresentative. Indeed, this type of evidence may not be the most appropriate measure of efficacy in the treatment of anorexia nervosa, and longitudinal observational study designs may provide equally valuable information (Reference Treasure and KordyTreasure & Kordy, 1998). The evidence base suggests that 20–24 sessions of out-patient therapy results in recovery in up to one-third of patients. Furthermore, the cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) model has demonstrable advantages over a purely behavioural approach, while CAT may be associated with greater subjective improvement than CBT, although the two are indistinguishable on objective outcome measures (Reference Channon, De Silva and HemsleyChannon et al, 1989; Reference Treasure, Todd and BrollyTreasure et al, 1995; Reference Treasure and WardTreasure & Ward, 1997b ).

The role of psychoanalytic psychotherapy is limited in anorexia nervosa (Reference Bruch, Garner and GarfinkelBruch, 1985). Interpretations may be experienced by the patient as repetitions of her early experience of others seeming to tell her how she should think and feel. This style of therapy is therefore best reserved for use by specialists in the eating disorder field.

A family therapy approach may be more appropriate for adolescent patients living with their parents than for older patients living away from home. A randomised controlled trial of treatment to prevent relapse in the post-treatment phase found that for those with onset prior to age 18 years and short duration of illness, family therapy is associated with a better outcome than individual therapy (Reference Russell, Szmukler and DareRussell et al, 1987). The converse was found in older patients. Interestingly, parental counselling and psychoeducation can be as effective as formal family therapy (Reference Le Grange, Eisler and DareLeGrange et al, 1992).

The emphasis between individual and family work should reflect a balanced consideration of age at onset, cognitive and emotional developmental level, degree of involvement with the family and chronological age. Conducting at least one family session is an essential part of treatment, omitted only if a family member has been involved in an abusive relationship with the patient.

Duration of therapy is dependent upon need but it should be borne in mind that brief, time-limited therapy is often followed by progressive improvement during follow-up, which can be maximised with occasional ‘top-up’ sessions. The number of sessions should be agreed at the outset of treatment such that an ending is explicit. The need for further therapeutic treatment can be discussed during ending and follow-up.

Josie, with onset age 18 years, remained entwined with her family with whom she lived. She saw herself as emotionally ‘weak’, a state she felt to be inappropriate to her 22 years of age. Indeed, her capacity to experience and manage difficult and painful emotions was extremely limited and frequently avoided in sessions. Although the mainstay of treatment was individual, a significant amount of family work was also undertaken. Since she had received CBT two years previously with good short-term effect, but ultimately relapse, a CAT model was used on this occasion. Therapy was time-limited to 20 sessions, with three top-up appointments during the following six months.

Family work

The aim of family work is to complete the formulation; to set realistic, shared expectations; to impart information; and to help the family provide appropriate support in the process of change. In the discussion of possible causes of anorexia nervosa, the therapist should make clear that this is a complex disorder for which there is no single cause – rather, genetic, psychological and social factors all play a part. Above all, apportioning of blame should be actively avoided.

Given the chronic nature of this disorder, families may become angry and critical, or distant and cold in response to the frustrations and difficulty of the anorexia. The motivational model is, again, a useful tool to explore resistance, elicit warmth and care, and to re-frame worries and concerns positively. If hostility and criticism persist, work with the family may need to focus upon sidelining critical members and facilitating separation.

Sometimes, it may be appropriate to recommend supportive counselling or more formal care for parents to help them manage their own difficulties as well as the difficulties imposed by anorexia nervosa. Teaching problem-solving skills may also be beneficial, since this is the only area in which parents of women with anorexia nervosa differ from others (Reference Blair, Freeman and CullBlair et al, 1995). Carer groups, which can sometimes be accessed through voluntary organisations such as the Eating Disorders Association, may also offer a valuable source of support and expertise. Anorexia Nervosa: A Survival Guide for Families, Friends and Sufferers (Reference TreasureTreasure, 1997) provides appropriate education and guidance in an accessible and acceptable format for patients, families and therapists.

Josie's family remained controlling and critical in sessions, disallowing expression of painful needs and feelings. It was also clear to the therapist that family secrets were held by Josie and her mother and unexpressed anger harboured towards the father. They did not take up the offer of couple counselling to help them manage difficult feelings and guilt about their daughter's illness, although they did read the Survival Guide. Josie decided that she needed to remove herself from the family home in order to make the necessary changes in her life but hoped that she would be able to tackle difficulties in her family relationships once she had established her autonomy. Her parents were supportive of her move from home.

The therapeutic alliance

Whatever the model of therapy used, the therapeutic alliance is an important mediator of change. Problems in the alliance arise when goals are not shared, when the therapist resists recruitment to the longed-for pattern of relating, or when the therapist colludes with maladaptive patterns of relating (Reference SafranSafran, 1993). For example, anorexia nervosa patients commonly recruit their therapist into a style of relating that affords them a sense of ‘specialness’ and safety, such as the ‘perfect care’ relationship. Therapist rejection of such longed-for roles may result in a retreat to the anorexia, experienced by the therapist as a cut-off, contemptuous patient who has no need of another. Alternatively, therapist and patient may collude in hostile maladaptive patterns of relating, arising from early experiences of hostile and inattentive others. Recognition of these maladaptive patterns of relating allows the experience of them to be talked about in sessions, facilitating a good therapeutic alliance in which non-collusion can be tolerated. Jointly made maps, or drawings, of the different relationship patterns and associated affects, are a useful tool with which to assist both patient and therapist in their attempts to identify and tolerate emotional and interpersonal experiences, both in and out of sessions. Such maps may function as important transitional objects, helping the patient to continue the work beyond therapy.

Ending is inherent in a time-limited psychotherapy and the disappointment, anger and other painful feelings experienced must be discussed in relation to the therapeutic relationship. The aim is to experience a different, more adaptive way of relating in which painful feelings and needs can be expressed, acknowledged and managed successfully.

Josie's therapist felt a continual need to try harder in order to help Josie. She shared this with Josie and wondered whether Josie might also be experiencing a strong desire to please in sessions. They talked about their experience of each other and their mixed feelings about the relationship and agreed not to try so hard to please each other. Avoiding collusion with conditional striving meant that Josie no longer felt special and accepted in sessions, but rather, experienced crushing shame and humiliation at her neediness. Josie initially experienced the therapist as ‘sorted and in control’ but as therapy progressed, she was able to see the therapist as having human failings. Gradually, Josie was able to accept her own needs and feelings as human also.

Cognitive schema

Current patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving, and core schema about the self are the snares that maintain anorexia nervosa as a compensatory mechanism. Issues such as low self-esteem and the schema of perfectionism and placation can be helpfully explored using the tools of the motivational model. For example, examination of the pros and cons of perfectionism may motivate change and facilitate discussion of the ways in which striving for perfect thinness may serve to compensate for the schema of worthlessness.

Josie believed that she was worthless and not entitled to feelings and needs of her own. Indeed, a pattern had become established in which Josie was perfectly attentive to the needs of her mother, while neglecting her own, leaving her feeling exhausted and needy. In her relationship with friends, Josie frequently listened to and supported others through difficulties, but believed that to do so herself was evidence of her own weakness. Josie's envious experience of the therapist as ‘perfect and in control’ helped her to imagine that her friends might actually like her more if she were to expose a little more of her human failings and needs. Using a problem-solving approach, role plays and the experience of the therapeutic relationship, Josie was able to gain the confidence to share her feelings and difficulties with friends and obtain support from them.

The example above is presented as a trap…

Striving to be perfect, Josie is left feeling needy and worthless which reinforces the need to be perfect.

These difficulties may also be expressed as a dilemma:

It is as if Josie has a dilemma that either she must be close to another and overwhelmed by his or her needs, or be self-sufficient but lonely.

…or a snag:

It is as if Josie is snagged, or held back from change, by her belief that to be of worth she must be perfect.

It may take many attempts before change in core schema is maintained and generalised. This is particularly so when societal influences, such as a culture-based idealisation of the androgenous thin body image, or significant others, are providing powerful reinforcement. Separation may not always offer resolution, since internalised representations of attachment figures may be persistent. Rather, it is the repeated working through of traps, snags and dilemmas in the context of a caring and collaborative relationship that may bring resolution.

Nutritional management

The balance between ongoing supportive nutritional psychoeducation (see Box 4) and active weight restoration strategies (see Box 5) should reflect a compromise between the patient's readiness for change and her nutritional status. A target weight should be negotiated and agreed with the patient. It should be a range that includes the premorbid weight, unless obese when a BMI of 20–24 is appropriate. A weight gain of 1–2 kg per week is a reasonable target for in-patients; a lower rate of gain is generally negotiated for out-patients. A frequent mistaken assumption is that if restraint on eating and weight is lifted, an all-consuming hunger will lead to massive weight gain. It is helpful to explain to the patient that the body establishes a set point for weight early in life and that some of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa arise from the body's efforts to regain this set point. The powerful systems that regulate weight around a set point ensure that it does not go beyond the healthy set point. Indeed, those who have recovered from anorexia nervosa tend to have lower set points for weight than their peer group, their weight tending to settle in the thin–normal range. This may motivate the patient to realise that she does not have to do all the work of controlling weight herself – systems are in place to do this for her.

Box 4. Psychoeducation: nutrition & weight

Fat, carbohydrate and protein are all necessary components of a healthy diet

Fat-free diet impairs absorption of vitamins A, D, E & K – vital for healthy bones, skin, vision and clotting

Where appropriate, educate about medical complications of bingeing and purging

Where appropriate, educate about the role of purgative behaviour in maintaining symptoms – e.g. purging increases hunger & removes reason for restraint → bingeing

Reduce activity – excessive exercise is damaging to bone density

Body image disturbance is a symptom of starvation

Body weight is regulated around a set point that is likely to be in the thin–normal range after recovery from anorexia nervosa

Box 5. Nutritional management

Negotiate target weight and rate of gain with patient

Calculate calories/day needed to achieve this target

Stop purging in order to stop bingeing and establish healthy eating pattern

Divide intake into three meals and three snacks per day – this prevents frightening experiences of hunger and reduces the likelihood of bingeing

Encourage consumption of a broader range of foods – no foods are bad foods!

Warn about complications of re-feeding – bloating, discomfort, constipation, oedema, hypercortisolaemia promotes central distribution of weight gain, increased emotional experience and distress, etc.

Enlist the help of a supportive, non-critical other

Re-teach shopping and cooking skills if appropriate

Psychopharmacological treatments

Depressive and obsessional symptoms are a common feature of anorexia nervosa and are in part secondary to starvation, tending to improve with weight gain. The value of antidepressants is unfortunately limited in the underweight state, and their use should be restricted to those with severe symptoms, or those who fail to improve with weight gain, on a trial basis. Given that a significant mortality arises from antidepressant overdose in anorexia nervosa, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the most appropriate choice (Reference Mayer and WalshMayer & Walsh, 1998).

The role of medication in assisting weight gain is also limited. Chlorpromazine, in small doses, may be useful in reducing anxiety. Fluoxetine may reduce relapse during weight maintenance and should be offered when the target weight is reached.

Medical complications

Medical complications can usefully be divided into acute and chronic consequences of malnutrition, purgative behaviours and re-feeding (see Box 3). All systems of the body are affected. Investigations are recommended at assessment, admission and at regular intervals during re-feeding (see Box 6).

Box 6. Recommended investigations

Haematology Full blood count and differential; erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Biochemistry Urea and electrolytes; creatinine; glucose; calcium and phosphate; liver function and albumin; amylase

Cardiovascular Pulse rate; blood pressure; peripheral pulses; electrocardiogram

Bone density DEXA bone density scan

Other Temperature Further investigation as indicated by clinical state

Some important aspects of management are covered below, but for a more detailed review, see Treasure & Szmukler (1995).

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a serious and common complication of chronic anorexia. It is of multifactorial causation. Oestrogen deficiency, hypercortisolaemia, malnutrition, vitamin D deficiency and adolescent onset all play a part. Therefore, treatment cannot simply be generalised from studies of post-menopausal osteoporosis.

DEXA bone scans and calcium supplementation should be considered for all those with more than a two-year history of anorexia nervosa. Evidence suggests that oestrogen therapy is of little benefit and in some cases may be harmful. It should therefore be reserved for those liable to remain chronically ill. Oestrogen therapy should never be given prior to epiphyseal fusion, or, obviously, to males. Weight restoration remains the treatment of choice (Reference Serpell and TreasureSerpell & Treasure, 1997).

Urea and electrolytes

Hypokalaemia, associated with vomiting and purgative misuse, can be extreme. It usually develops gradually and rapid correction can be associated with greater morbidity and mortality than non-intervention. Nutritional advice to eat high potassium foods, such as bananas, or to use potassium supplements, is therefore the treatment of choice.

Summary

Treatment strategies should aim to be collaborative with an emphasis upon a good therapeutic alliance. The motivational model is ideally suited to this purpose and should be used throughout treatment whenever resistance is encountered. Indeed, resistance is more helpfully conceptualised as a lack of matching between therapist intervention and patient readiness for change, and indicates need for a change in treatment strategy. Brief out-patient therapies are the treatment of choice and family involvement should be encouraged in most cases. Weight should be charted at every contact, providing an invaluable, objective guide to progress. Attention to medical complications is important and investigations can usefully be fed back to patients to enhance motivation. Mortality and morbidity are extremely high and it is inappropriate to allow underweight patients to refuse treatment without specialist assessment and consideration of compulsory admission. Threshold for referral to specialist services should be low.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. In-patient treatment of anorexia nervosa:

-

a is the treatment of choice

-

b should always be voluntary

-

c has better outcome than out-patient treatment

-

d is best provided by specialist centres

-

e is indicated if out-patient treatment has failed.

-

-

2. In the assessment of patients with anorexia nervosa:

-

a patients usually present in the stage of active change

-

b patients are frequently ambivalent about change

-

c reflective listening can be used to enhance motivation

-

d positive aspects of the illness should be acknowledged

-

e interventions need not be matched with the stage of change.

-

-

3. Regarding medical factors:

-

a medical complications improve with weight gain

-

b osteoporosis is a common chronic complication

-

c hypokalaemia usually develops rapidly

-

d osteoporosis should always be treated with oestrogen

-

e calcium supplements may improve osteoporosis.

-

-

4. Regarding psychotherapy:

-

a psychodynamic psychotherapy is suitable for all patients with anorexia nervosa

-

b family work is an important component of treatment

-

c parental counselling and psychoeducation is as effective as family therapy

-

d the therapeutic alliance is an important mediator of change

-

e unshared goals of therapy are an obstacle to the therapeutic alliance.

-

-

5. In the treatment of anorexia nervosa:

-

a antidepressant medication is invaluable

-

b selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may reduce relapse after weight restoration

-

c education is a critical part of nutritional management

-

d BMI 20–24 is the healthy range

-

e absolute BMI and rate of change in weight should guide management.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | T | a | F | a | F |

| b | F | b | T | b | T | b | T | b | T |

| c | F | c | T | c | F | c | T | c | T |

| d | T | d | T | d | F | d | T | d | T |

| e | T | e | F | e | T | e | T | e | T |

Fig. 1. The transtheoretical model for change (adapted from Prochaska & DiClemente, 1992)

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.