History is littered with the remains of failed democracy movements. In many nondemocratic countries, movements seeking civil liberties and self-determination have appeared suddenly and unexpectedly. In most cases, however, activists underestimate the determination of elites to resist calls for change. Ultimately, most democratic movements in authoritarian regimes end badly, with violent suppression of protest, the imprisonment or even execution of activists, and increased restrictions on freedoms and civil society that may last for decades.Footnote 1

Most of these defeated movements are forgotten except to historians, cast aside as failures, and receive little scholarly focus except in analyses of why some movements fail and others succeed. Yet, understanding the enduring impact of such movements on attitudes is critically important for understanding the prospects for and processes toward democracy in authoritarian regimes. The attitudinal impact of democracy movements can reveal both the potential for rapid adoption of new attitudes and the power of the state to suppress and prevent them. A broad literature asserts that democratic values are acquired gradually through socialization. Can limited exposure to democratic ideals and civil society substitute for this socialization in the development of democratic attitudes? Do movements leave any mark on attitudes? Or, are authoritarian governments able to suppress and erase any echo of such movements?

Scholarly attention to these questions has been quite limited, largely, we believe, due to the great difficulty in collecting empirical evidence. By definition, such movements have been repressed and authoritarian regimes would prefer that they be forgotten. Former activists, if still living, may be unwilling to speak of their experiences, and it is often illegal to simply ask about participation in a repressed social movement. Further, even if we could identify and speak openly with participants, most studies of movements’ impact on participants have a severe endogeneity problem, because individuals with especially strong attitudes would be those most likely to join a movement in the first place.

In this paper, we offer an innovative identification strategy to address these challenges and investigate the long-term impact of one of the largest and most important of failed democracy movements: the Chinese student movement of 1989. This movement culminated in the Tiananmen Incident,Footnote 2 when the Chinese government sent security forces to clear Tiananmen Square of protestors, with thousands of casualties (Wong Reference Wong1997).

Besides being one of the most important contemporary democracy movements, this case provides a rare opportunity to measure the impact of social movements on attitudes in an authoritarian society. Although researchers cannot directly measure or even directly ask about participation in the movement, a focus on college students provides a reasonable proxy for exposure, if not participation. Students in college in Beijing in the spring of 1989 were exposed to the lively democracy movement on campus and the crackdown that followed; those who began in the fall of 1989 experienced a controlled and muted political environment. Thus, a comparison of these two groups—those who started college before the Tiananmen Incident, and those who started immediately after it—provides as clean a test as one is likely to find of the long-term impact of these democracy movements and their repression. Differences between these groups 30 years after the Tiananmen Incident would be evidence that even failed democracy movements can profoundly affect attitudes.

Our analysis shows a significant impact of the movement on democratic attitudes. Students in college during the movement have consistently higher support for democracy and are more likely to understand democracy in terms of intrinsic freedoms and rights, rather than instrumental or performance-based terms, when compared with those who only started college in the fall of 1989 or later.

We further address two potential challenges to our design. First, year of admission itself could be endogenous, so we use an exogenous variable, birthdate, as an instrument for exposure to the movement, and we estimate a fuzzy regression discontinuity which largely validates our original results. This innovative approach allows scholars to estimate causal effects when the assumption of a strict assignment threshold is not met, as in our case where birthdate does not perfectly determine college enrollment year. Second, we consider whether these differences were caused by participation in the movement by the Tiananmen cohort, or by the state repression experienced by the post-Tiananmen cohort. We separately analyze universities with high and low exposure to the movement, finding that the impact of the movement was greatest among alumni of high exposure campuses. These differences provide partial evidence that participation in the movement, not its repression, explains the long-term difference in attitudes. They suggest that the primary impact of the movement was to broadly increase understanding of procedural democracy and, for those most involved in the movement, to inoculate them against the performance-based legitimacy claims of the regime.

DEMOCRACY, AUTHORITARIANISM, AND POPULAR MOVEMENTS

Our goal is to learn about the impact of social movements on democratic attitudes in authoritarian regimes. Do democracy movements affect attitudes, even when those movements fail? We focus on democratic attitudes because freedom and democracy were among the Tiananmen movement's core organizing principles, slogans, and published demands (Zhang Reference Zhang2001). The student movement in this case clearly failed to achieve its broader aims, as the movement was violently suppressed and has been largely erased from official memory, and citizen rights and freedoms have been reduced since 1989. Even so, the experience of participating in the movement and the state violence that crushed it may have affected participants and left an impact on participants and bystanders.

While there is a voluminous literature on social movements, very little work directly addresses our question: how does participation in movements affects democratic attitudes in non-democracies? The majority of the literature focuses on explaining whether movements succeed or fail, and such analyses are usually limited to Western democracies. By success or failure, analysts typically examine whether movements were able to affect public policy or coalesce into enduring political parties (Giugni Reference Giugni2008; Amenta et al. Reference Amenta, Caren, Chiarello and Su2010). Outcomes are predicted by movement resources, strategy, and the contextual factors (Jenkins Reference Jenkins1983; McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977; Burstein, Einwohner, and Hollander Reference Burstein, Einwohner, Hollander, Craig Jenkins and Klandermans1995). Although regime type would seem an obvious and important contextual factor affecting social movements, it is rarely considered, and nearly all previous research only examines movements in democratic systems.

A smaller literature examines how social movements affect participants and bystanders. We are unaware of any existing work on how social movements affect democratic attitudes in authoritarian regimes, but existing research does offer insights on the mechanisms, scope, and persistence of social movement effects on other attitudes. This research spans a diverse set of dependent variables, including family and childbearing choices and patterns (McAdam Reference McAdam1989; Giugni and Grasso Reference Giugni, Grasso, Bosi, Giugni and Uba2016; Giugni Reference Giugni2004), future activism (Corrigall-Brown Reference Corrigall-Brown2012), and even career choices (Fendrich Reference Fendrich1974; McAdam Reference McAdam1989).

Research on how movements affect political attitudes focuses on efficacy, as well as participants’ alignment with movements’ positions. Regarding the former, scholars have examined how participation affects individuals’ sense of efficacy, including trust and sense of political empowerment (Finkel Reference Finkel1985; Opp Reference Opp1998; Pateman Reference Pateman1970). Finkel (1987), studying protest in West Germany, finds that aggressive protest behavior can reduce regime support, and that political campaigning increases political efficacy. Studying a rare case of a successful democracy movement in an authoritarian regime, Opp (Reference Opp1998) compared attitudes in East Germany before and after democratization, finding that participation in the democracy movement in 1989 increased efficacy and satisfaction in 1993.

Regarding political beliefs, a number of scholars have investigated how participation in movements can lead to long-term changes in policy preferences. Scholars examining the consequences of the civil rights and anti-war movements in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, consistently find that these movements have permanently shifted attitudes of former participants, when compared with non-participants.Footnote 3 Former participants have adopted and extended the positions of the movements, and decades later are consistently more liberal and more political than former non-participants. The literature offers a series of mechanisms that explain how these shifts in attitudes occur and are preserved. The interaction of participants can lead them to adopt and reinforce a movement's norms and positions. Participation in this new protest community permanently changes attitudes, which McAdam (Reference McAdam1989) calls “a conversion-like experience.” These changes affect more than policy attitudes. They also affect life choices and beliefs outside the area of the movement (Sherkat and Blocker Reference Sherkat and Jean Blocker1997).

In addition, recent work suggests that, more than just affecting participants, movements can also affect the efficacy of non-participant observers. Examining immigrant rights movements in the United States, Wallace, Zepeda-Millán, and Jones-Correa (Reference Wallace, Zepeda-Millán and Jones-Correa2014) find exposure to more protests leads to higher efficacy in surrounding areas, although especially large protests may reduce efficacy. Branton et al. (Reference Branton, Martinez-Ebers, Carey and Matsubayashi2015) examining the same set of protests, show that the movements increased public support for their policy goals. Those with greater exposure to the movement reported greater support for more liberal immigration policies. Further, Carey, Branton, and Martinez-Ebers (Reference Carey, Branton and Martinez-Ebers2014) show that movements increase the saliency of their issues.

Although research on the impact of movements on attitudes in nondemocracies is limited, several scholars have extended these questions to movements in China, testing whether activism and participation in local movements increases efficacy. Findings echo research in democracies and suggest that movements’ impact may be even greater in non-democracies. Scholars describe participation in movements as a life-changing experience affecting both participants and observers. For example, in their qualitative study of protest leaders and other villagers in Hengyang County in Hunan Province, O'Brien and Li (Reference O'Brien and Li2005) interviewed activists and concluded that collective action had effects on their attitudes and life course. The multi-faceted attitudinal consequences of participation included a general sense of efficacy from modest successes. For example, villagers who simply obtained public information reported dramatic feelings of efficacy. These effects extended to non-participant observers: villagers not involved in the protests were willing to increase their engagement in politics by “participat[ing] in fund-raising or daring acts of defense when protesters are detained or face repression” (O'Brien and Li Reference O'Brien and Li2005, 249).

In addition, an emerging literature examines the impact of ongoing protests in semi-democratic Hong Kong. Findings suggest that simple participation in protest does not change attitudes (Bursztyn et al. Reference Bursztyn, Cantoni, Yang, Yuchtman and Jane Zhang2019), but that access to information and encouragement to seek it does affect political opinions (Chen and Yang Reference Chen and Yang2019). However, these movements have not yet suffered (at the time of this writing) the violent repression and subsequent censorship that are typical in the most authoritarian cases, and it is not clear if Hong Kong's semi-democratic political system is comparable to the environment of the 1980s in mainland China.

Our study of the long-term effects of exposure to the Tiananmen movement will extend these findings to the question of how exposure to a failed movement affects democratic attitudes. No previous work has examined how such movements affect support for and understandings of democracy. This may not be surprising, as nearly all this work has been conducted in democratic settings, where support for democracy as a form of government may be taken for granted. Yet, this remains a critical and understudied question for social movements in nondemocracies. A large literature suggests that democratic values are developed over generations. Can movements like that observed in China in 1989 jump-start attitudinal change? In the case of the Tiananmen movement, given that democratization was itself a goal of the movement, we may expect that exposure to the movement increased democratic support. In addition, just as participation in the civil rights movement created enduring support for progressive political positions among participants, those involved in the Tiananmen Incident describe it as a dramatic and life changing experience (below), suggesting that these attitudinal changes should have persisted over the 25 years from the event until our survey of 2014.

One complication is that democracy movements in authoritarian regimes nearly always end badly, often with great personal cost and suffering to participants. The treatment in our study, exposure to the movement, naturally involves more than observing, marching, and organizing. As a failed movement in an authoritarian state, exposure also involves the state violence that ultimately ended the movement.

Surprisingly little has been written on the impact of violence on attitudes; most research on state violence focuses on the choice by state actors to use violence or the factors that can prevent state violence (Davenport Reference Davenport2005; Reference Davenport2007; Davenport et al. Reference Davenport, Nygård, Fjelde and Armstrong2019; Starr et al. Reference Starr, Fernandez, Amster, Wood and Caro2008). One interesting finding from this literature is that state violence can increase trust and support for the regime. However, this research examines attitudes in the general population, not just victims of violence (Garcia-Ponce and Pasquale Reference Garcia-Ponce and Pasquale2015).

Recently, some scholars have begun to examine attitudinal consequences of repression and violence, but findings and specific contexts vary greatly, making generalization difficult. For example, Blattman (Reference Blattman2009) and Bellows and Miguel (Reference Bellows and Miguel2009) find greater participation in democratic politics by those who suffered more conflict-related violence. In contrast, Zhukov and Talibova (Reference Zhukov and Talibova2018) and Rozenas and Zhukov (Reference Rozenas and Zhukov2019) show how state repression reduces long-term participation and increases regime support when citizens are under threat. For our project, the closest relevant work is that of Burchard (Reference Burchard2015), who finds that Africans exposed to political violence have weaker democratic attitudes. Note that, as with the social movements’ literature, this emerging line of inquiry focuses primarily on electoral violence in young democracies rather than the impact of state violence in authoritarian regimes.

Lastly, we also offer several methodological contributions. The first is to provide a general framework for studying movements’ impact in non-democracies. Often in such cases, participants cannot be identified, and individuals cannot be asked about participation, and they would not answer if asked. This is the case today in China. However, we can take advantage of college enrollment patterns to identify individuals with more or less exposure to the movements, although we cannot directly ask about the extent of exposure. Second, we can address endogeneity in participation with our approach. The vast majority of extant work risks endogeneity, since in most cases individuals self-select into participation and thus may already be different than those who have no contact with the movements. As college enrollment decisions predate the movement, we expect them to be orthogonal to any existing attitudinal differences. Further, to address the risk that later enrollment decisions may be endogenous, we also instrument for exposure using respondents’ birth dates. These approaches allow us to identify the impact of exposure to the movement, with some caveats, discussed below.

THE TIANANMEN MOVEMENT OF 1989

In the spring of 1989, over 100,000 Chinese students in Beijing mobilized in the largest student democracy protest in human history (Zhao Reference Zhao2001). For almost two months, student-led popular demonstrations at Tiananmen Square called for freedom of speech, a democratic form of government and government accountability.

The movement began after the sudden death on April 15, 1989, of Hu Yaobang, former General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The first mobilizations of students were to honor and memorialize his legacy (Pan Reference Pan2009), but they quickly evolved into protests with political demands (Zhao Reference Zhao2001). On April 23, an independent students’ organization, the Beijing Students’ Autonomous Federation, was established. The students published a list of demands, which included freedom of speech, democratic elections, freedom to assemble and demonstrate, and more. The demonstrations that followed were the most widespread students protests since the end of Cultural Revolution in China (Béja and Goldman Reference Béja and Goldman2009), and they were accompanied by riots, unrest, and looting.

The government's initial response was mild, but as the movement grew, the leadership took a stronger stance. On April 26, People's Daily, the CCP's official newspaper published a front-page article titled “We Have to Take a Clear-Cut Stand against Disturbances” (People's Daily 1989). The newspaper labeled the student movement as an anti-government, anti-party revolt. This article angered and further mobilized students, becoming a major turning point of the protests (Vogel Reference Vogel2011). On April 27, an estimated 100,000 students marched from their university campuses toward Tiananmen Square with signs and chants against corruption and cronyism (Zhao Reference Zhao2001). As the situation deteriorated, students mobilized in Tiananmen Square for a hunger strike starting May 13 (Zhao Reference Zhao2001). One week later, the Chinese government declared Martial Law and soldiers were sent to the capital. Finally, beginning in the evening of June 3 and continuing into the morning of June 4, the army cleared Tiananmen Square by force.

The regime's short-term solution to the challenge of the movement was repression, but the longer-term strategy has been increased control to prevent future protest and reform movements. Immediately after the Incident, government control of censorship, public communication, and civil society were all tightened. Anti-regime protests were quickly dealt with and became extremely rare. Discussion of Tiananmen was discouraged, and press coverage was limited. Even today, few will openly admit to having been in the square during the protests. For many, it is as if the protest movement never happened (Beam Reference Beam2014; Lim Reference Lim2014). The incident interrupted economic reform, which did not resume until Deng Xiaoping's 1992 Southern Tour, and scholars agree that the movement and its aftermath delayed any prospects for political transition (Perry Reference Perry2007).

The tighter control of civil society and speech mean that students after Tiananmen have had a very different experience than those in university before and during the Tiananmen Incident. Students in college through June 1989 would have been exposed to a dynamic movement of independent organization and protest, to diverse discussions and speeches about democratization and reform, and to the potential power of activism. Those entering college in fall 1989 or later would have experienced a sterile and tightly controlled political environment, where activism and speech were suppressed and controlled. The nature of the Incident has created a natural contrast between the two cohorts, as well as an opportunity to test for the long-term impact of democratic social movements. The design, discussed below, is not perfect, but it is difficult to imagine a case that provides a cleaner test in an authoritarian regime.

DESIGN AND IDENTIFICATION

Our goal is to measure the impact of the Tiananmen Incident on democratic attitudes of participants. Examining the impact of a democracy movement on attitudes in an authoritarian regime is typically impossible, given the usually insurmountable challenges of measurement and confounding. In a non-democracy, subjects are unlikely to discuss their participation, or even exposure to the movement. This is certainly the case in China regarding the June Fourth Incident, where it is not publicly discussed, few will admit to having participated, and it is unlikely that any survey firm would agree to field direct questions about the Incident.Footnote 4 Further, for most social movement studies, an additional challenge would be selection bias; participation in a spontaneous popular movement is a choice, and it is likely the case that those with the strongest democratic values would also be those most likely to choose to participate in the first place. Both of these considerations suggest that clean identification of the impact of a democracy movement would be nearly impossible.

We address both challenges by comparing students in college in the spring of 1989 with those who began college in the fall or later, after the movement. Being enrolled in college in spring 1989 versus enrolling for the first time in fall 1989 or later divides students into those who were exposed to the movement and could participate in it, and those who had little or no exposure. Thus, college enrollment year determines level of exposure to the movement. In addition, enrollment year for most students will be exogenous, since year of enrollment in college is primarily determined by the year one started kindergarten (details below). We refer to the cohort in college in 1989 as the treatment group or Tiananmen cohort, and the cohort that began college after 1989 as the control group or post-Tiananmen cohort.

There is some risk of endogeneity in timing of enrollment, which we address with a fuzzy regression discontinuity, using birthdate as an exogenous predictor of enrollment date. Our measurement and design are not perfect, but we cannot imagine a cleaner test in a situation where the key independent variable cannot be mentioned or discussed with respondents. We present our strategy below, then consider weaknesses and our attempts to address them.

Our first challenge is to measure exposure to the movement without directly asking any respondents about their participation. The nature of the student movement in 1989 gives us an opportunity to do so. For those in college in the spring of 1989 in Beijing, evidence suggests that the overwhelming majority of students had some direct participation in the movement and that virtually all students were exposed to the movement's members, ideas, and activities. The movement was student-initiated and student-led (Oksenberg, Sullivan, and Lambert Reference Oksenberg, Sullivan and Lambert1990; Wasserstrom Reference Wasserstrom2010), and observers have described universities in Beijing at that time as awash in mobilization and democracy fervor, with lively discussions, organization and protest, portraying a movement and mobilization that simply could not be ignored. One protestor who fled China after the movement described the campus environment as “absolutely electric” and “a chemical reaction producing something new and kinetic” (Schell Reference Schell1989). The sheer size of the movement suggests that it involved the majority of all students in Beijing at that time. For example, in 1989, there were approximately 141,600 students across 67 institutions of higher learning in Beijing. Observers and historians have estimated that during the demonstration of April 27, 100,000 college students marched to Tiananmen Square. Thus, more than 70 percent of students in Beijing directly participated in the march of April 27—just one of many activities of the movement (Oksenberg, Sullivan, and Lambert Reference Oksenberg, Sullivan and Lambert1990). Given the great deal of excitement, enthusiasm, and interest in the movement, it seems likely that most students had some level of participation in it. And even for that minority of students that did not directly participate, they almost certainly had considerable exposure to the movement: they witnessed the activities, knew the participants, and learned about the motives and aims of the movement.

In contrast, future undergraduates—those who enrolled in fall 1989 or later—would have had significantly less exposure to the movement. These individuals were mostly minors, living with their parents and attending high school, many living outside the major cities where protests occurred. In addition, the final year of high school for college-bound seniors is an extremely intense experience in China, with students’ free time overwhelmed by test preparation. High school students received most of their information about the movement through the pro-government media, which became especially anti-protest after the April 26 editorial (Newsweek Staff Reference Staff2015). Finally, once these younger students started college, the campus environment had changed dramatically. The student democracy movements had been purged from campuses and the government was firmly in control of the media. The result is that individuals who were too young to enroll in college in the fall of 1988 had limited direct exposure to the student movement or its suppression.

For political attitudes, these contrasting experiences should be especially formative. Research in identity, including political identity, finds that adolescence and early adulthood are formative years in the evolution of beliefs and sense of self (Erikson Reference Erikson1950; Reference Erikson1968; Marcia et al. Reference Marcia, Waterman, Matteson, Archer and Orlofsky1993; Jennings and Niemi Reference Jennings and Niemi1974). If the movement had an attitudinal impact, it should be evident among those who were students at that time.

Our measure of exposure is not perfect, of course, and could easily be inaccurate for some respondents. Among those in college in 1989, given the atmosphere and the mass participation in protests, we believe that nearly all students were exposed to the movement's presence, activities, slogans, and aims, and a majority were participants in at least one event. However, mere status as a college student in Beijing in the spring of 1989 does not tell us whether individuals were active participants or leaders, whether they were in Tiananmen Square when the army arrived, or whether they merely observed the turmoil without attending any events. We will partly address this in a secondary analysis.

In addition, some students in the control group (those not yet in college) may have been exposed to or participated in the movement as high school students. As many observers have noted, there were high school students in Tiananmen Square, and these students had broad exposure to the Tiananmen Movement. Some even organized high school marches and protests in support of the college students. We believe this mismeasurement will not be problematic for our analysis for two reasons. First, any exposure of high school students to the movement weakens our findings. High school students who were part of the movement should have been equally affected by it, so their attitudes today should be similar to those of the Tiananmen cohort. Consequently, this pollution of exposure weakens the power of our test, and any significant findings are thus especially robust. Second, simple probabilities suggest that this type of pollution is a limited problem. Although there were many high school students in Tiananmen Square, only about 1 percent of high school students went on to college in the early 1990s, and many college students came from outside Beijing. Thus, even though many high school students were participants in the movement, it is likely that very few of them were able to attend college in Beijing shortly after the Tiananmen Incident.

Our design also attempts to address the problem of self-selection into protest movements. In most studies, it is not clear whether participation in the movement causes attitudes, attitudes cause participation, or both. As a result, estimating the impact of one on the other is difficult. Those with high pre-existing levels of democratic support are those most likely to join democracy movements. In our design, the key determinant of exposure to the movement—enrollment year—is essentially exogenous. Most students will enroll in college as soon as possible. Assuming a normal progression through the education system, this is typically the year after high school. In cases where enrollment is earlier or later, these decisions typically reflect idiosyncrasies of family choices and local schooling. Most education decisions were made well before the Tiananmen Movement in the spring of 1989, which emerged spontaneously in reaction to an unexpected death of a senior leader.

Some might be concerned that other factors might have affected enrollment year decisions and created some pre-treatment differences across cohorts. To address this possibility, we conduct a fuzzy regression discontinuity analysis, using birth date as an instrument for year of college enrollment. We note that students’ enrollment year is primarily determined by an exogenous variable, age. In theory, there is a sharp discontinuity associated with birthdate that determines whether one received treatment or control. In China, elementary and middle school are both required, and high school is required to take the college entrance examination. Elementary education begins at age seven, with a theoretically strict age cutoff in September.Footnote 5 Thus, a child born on August 31, 1970 would have enrolled in first grade in September of 1977, started middle school five years later, in 1982, and began high school in the fall of 1985. The student would sit for the college entrance examination in the summer of 1988 and be eligible to enroll in college in the fall of 1988, placing him or her on campus for the democracy movement spring 1989. In contrast, a student born on September 1, 1970 would have started elementary school in 1978, middle school in 1983, high school in 1986, and, in theory, only have enrolled in college a year later, in fall 1989, completely missing the Tiananmen movement.

If birthdate perfectly predicted college enrollment, we could use a Regression Discontinuity Design (Thistlethwaite and Campbell Reference Thistlewaite and Campbell1960), and consider the treatment status of those born before and after September 1, 1970, as if they were randomly assigned to attend college during the protest movement or during the post-protest period. However, assignment is not sharply determined by birthdate for several reasons. Parents and school officials may not have complied with the cutoff, holding children back or pushing them to enter school early. Students might have failed the college entrance examination on a first try, then passed successfully on a second try. Some provinces may have required a sixth year of elementary education, instead of five years. Any of these could lead to a student enrolling in college a year earlier or later than the cutoff would have predicted. However, all students had strong incentives to attend college as early as possible, and none of the factors mentioned above would have allowed a student to select into or out of the unexpected movement that emerged in the spring of 1989. To the extent that there was selection into or out of particular cohorts, a sharp RDD would not be appropriate, but an alternative is a fuzzy RDD (Lee and Card Reference Lee and Card2008; Lee and Lemieux Reference Lee and Lemieux2010).

A Fuzzy Regression Discontinuity Design (FRDD) exploits the logic of a standard regression discontinuity, but addresses the case where assignment is not precise and there is some chance of selection effects or endogeneity. Fuzzy RDD leverages an exogenous running variable and uses an approach very similar to that of an instrumental variable estimation; indeed, the connection between instrumental variables and fuzzy RDD was shown by Hahn, Todd, and van der Klaauw (Reference Hahn, Todd and van der Klaauw2001), who suggest a 2SLS approach. Thus, the analyst first uses the exogenous running variable to predict treatment assignment, then analyzes how predicted treatment affects the dependent variable. In our case, that means first using birthdate to predict whether the respondent was in college during the spring of 1989, then using predicted treatment status as an independent variable in the final models. The primary cost of this approach is that is has lower power than a simple OLS, so it is more likely to yield insignificant estimates. We will report both OLS and FRDD models.

An important weakness of our design is that there are multiple pathways from the Tiananmen movement to attitudinal outcomes, because the movement had far-reaching effects on China's trajectory, some of which are difficult or impossible to disentangle from each other. First, students in the Tiananmen cohort participated in or were bystanders of this social movement: the marches, speeches, protests, and wide-ranging discussions about China's future. As observed in other social movements, this exposure could reshape beliefs and attitudes about democracy, as that was one of the main demands of the movement. Attitudes could also be reinforced through the uniqueness of this experience with an independent civil society movement, a first for virtually all participants, which they described as life-changing. Students who only started college post-Tiananmen had little or no direct contact with the movement, and most of their knowledge would have come from state-controlled media.

Second, the students in the Tiananmen cohort were also victims, or knew victims of the state violence that ended the movement. Given protestors’ peaceful aims and mobilization, this violence was extremely traumatic. Those in the post-Tiananmen cohort would largely not have been exposed to or suffered this violence.

Third, the Tiananmen movement fundamentally changed China's political trajectory. The 1980s were a period of gradual opening and liberalization with greater tolerance of dissent. The June Fourth Incident was a critical juncture, after which the regime tightened control and restricted political freedoms and liberties, a trend that continues today. Students who were in the Tiananmen cohort began college in a more open environment with greater freedoms on campus, including debates about political systems and related topics. After the movement, the regime imposed re-education programs and bootcamp-like instruction on some campuses and dramatically changed the college environment. Students who were in the Tiananmen cohort experienced both environments (unless they graduated in spring 1989); students who were in the post-Tiananmen cohort only experienced the stifled environment that came after the Incident.

Thus, there are at least three mechanisms linking the movement to attitudes. Regarding the first two, the activities of the movement and its violent suppression, we cannot imagine any way to disentangle their independent effects. Indeed, exposure to state violence is often an intrinsic part of participation in a social movement in an authoritarian regime. As we cannot disentangle these two, when we discuss “exposure to the movement” or “participation in the movement,” we intend this to mean both the protest and demonstration activities as well as exposure to the state violence that ended the movement.

The third possible mechanism is that attitudes are affected not by participation in the movement but rather through the broader changes in the political environment associated with a crackdown. According to this hypothesis, students in school before the crackdown experienced some socialization in a relatively open and liberal environment, where post-Tiananmen the environment was much more controlled and restricted. Note that any such effect is also caused by the movement, but in this case the effect is indirect. The movement would cause a change in the broader environment, and this broader change would lead to different attitudes. We note, however, that interviews and qualitative descriptions of the movement emphasize the dramatic and powerful impressions of the movement—not of the college experience. Consequently, we hypothesize that direct exposure to the movement and its repression was the more important pathway for affecting attitudes.

Although we cannot directly test for the influence of one mechanism or the other in our study, we will employ a series of indirect tests. Combined, they suggest that direct exposure to the movement and its suppression was the primary factor shaping attitudes, as opposed to the indirect effects of changes in the campus environment.

DATA

Our data come from a survey of 1,208 adults in Beijing conducted from May 2015 to September 2015 by the Research Center for Contemporary China of Peking University (RCCC). Our population of interest is college graduates between the ages of 40 and 49 (in the summer of 2015) who attended college in Beijing. The survey asks respondents a series of questions about political attitudes, standard demographic information, and details on the years that they were studying at university as well as their birth years and months, which will be used to measure exposure to the student movement. Some survey questions asked about respondents’ political attitudes, which led to many potential respondents refusing to take the survey via email, face to face or telephone. Consequently, RCCC sampled additional potential respondents from their database who satisfied the age requirement (40–49 in the summer of 2015) and educational requirement (attended college in Beijing). Then, RCCC sent emails to potential respondents and asked them to take an online survey. Table 1 reports the number of respondents by survey method.

Table 1 Survey Methods and Number of Observations

For our dependent variable, we sought survey-based measures of democratic attitudes. However, respondents in different countries, with different traditions may interpret the term “democracy” very differently. As one example of this, a consistent finding in the literature has been high levels of support for democracy in authoritarian countries. Indeed, democratic attitudes in some authoritarian regimes are much higher than those in countries that are often thought of as highly democratic.Footnote 6

The explanation for these results has been found in how respondents interpret questions about democracy. Responses to questions about support for democracy or similar questions can only be answered in the abstract in authoritarian regimes, whereas subjects in democracies can draw on both abstract concepts and their personal experiences when choosing responses (Rose and Mishler Reference Rose and Mishler1996). As a result, survey respondents in democracies may be appear less democratic, because their responses may only reflect criticism of the performance of an incumbent government. In contrast, respondents in authoritarian regimes are evaluating an abstract and perhaps misunderstood ideal regime type. These respondents might associate democracy with the economic achievements of consolidated democracies of North America and Western Europe: wealthy and powerful countries with a very high standard of living. More than different regime types, culture may shape understandings of democracy. Research on China and Asia has suggested that Confucian tradition leads to an alternative definition of democracy where governing legitimacy comes from positive social outcomes, not electoral procedures (Shi and Lu Reference Shi and Lu2010). We adopt two strategies from the literature to address the challenges of measuring democratic attitudes across culture and context. First, following Bratton, Mattes, and Gyimah-Boadi (Reference Bratton, Mattes and Gyimah-Boadi2004), we examine the demand for and supply of democracy, and calculate their difference. Respondents were asked about the suitability of democracy for their country, which we will refer to as Demand for Democracy. Respondents were also asked to rate the current level of democracy in their country, which we will call the Supply of Democracy. Finally, we calculate the difference between supply and demand, which we call Support for Democracy.

More precisely, we use the following two questions:

Demand for Democracy: “If ‘0’ Means that democracy is completely unsuitable for our country today and ‘10’ means that it is completely suitable, where would you place our country today?”

Supply of Democracy: If ‘0’ means entirely undemocratic, and ‘10’ means entirely democratic, please tell us how democratic you believe our country is under the current regime?”

We then calculate the Support for Democracy as the difference between supply and demand:

Support for Democracy = Demand for Democracy − Supply of Democracy

When demand exceeds supply (support is positive), one interpretation is that the respondent would like to see more democracy; when supply exceeds demand (support is negative), the respondent would like less democracy. When support is close to zero, respondents find the current level of democracy to be appropriate for their country.Footnote 7

Since democracy and elections were central aims of the 1989 movement in China, these questions will allow us to see whether exposure to the movement increased individuals’ support for the movement's aims. As discussed above, research in democratic contexts found that exposure to protests increased subjects’ support for social movements’ aims (Branton et al. Reference Branton, Martinez-Ebers, Carey and Matsubayashi2015; Carey, Branton, and Martinez-Ebers Reference Carey, Branton and Martinez-Ebers2014).

A second set of questions examines subjects’ definitions of democracy. Following Bratton and Mattes (Reference Bratton and Mattes2001), we contrast intrinsic and instrumental definitions of democracy. Intrinsic features are, “democracy for democracy's sake,” reflecting support for core values of elections and personal freedom. Instrumental understandings of democracy are performance-based. Democracy is associated with many positive outcomes for human welfare, and it may be that respondents understand democracy to indicate positive performance. To accomplish this, the survey asked respondents whether economic growth, income equality, election of leaders, and civil rights were essential characteristics of democracy. We combined these into an Intrinsic-Instrumental scale. We expect that respondents in college during the movement will rate intrinsic characteristics higher and instrumental characteristics lower than respondents who began their studies after the Incident. Of course, these survey questions cannot capture all of the nuances of possible interpretations of democracy, but the questions provide a comparable baseline that has been validated in other studies.

For the intrinsic versus instrumental interpretation of democracy, we use the following questions:

If “0” represents completely disagree and “10” represents completely agree, to what extent do you agree that the following things are essential characteristics of democracy?

1. Political Rights: “People choose their leaders in free elections.”

2. Civil Liberties: “Civil rights protect people from state oppression.”

3. Income Equality: “The state makes people's income equal.”

4. Economic Growth: “The state delivers economic growth.”

The first two questions indicate the degree to which a respondent's understanding of democracy is intrinsic, and oriented toward features of the political system. The last two questions measure instrumental democracy, which is based on economic performance of the state (Bratton and Mattes Reference Bratton and Mattes2001). All four of these questions come from the World Values Survey.Footnote 8 The four are combined in the Intrinsic-Instrumental index, calculated as follows:

Intrinsic-Instrumental Index = (Political Rights + Civil Liberties) − (Economic Growth + Income Equality)

These questions will allow us to test whether exposure to the movement increased participants’ knowledge about politics and regime type. Larger values indicate greater support for definitions of democracy based on rights and liberties; smaller values signal greater weight on economic performance when defining democracy.

We expect more support for democracy, higher demand for democracy, and lower supply of democracy among the treated subjects than control subjects, as discussed above. We also expect respondents who experienced the movement to report relatively more agreement that political rights and civil liberties are intrinsic characteristics of democracy, than respondents who did not experience the movement. Finally, treated respondents should have lower agreement with instrumental characteristics of democracy than control respondents. Our hypotheses were preregistered and our preregistration plan and details on deviations from that plan are included in the appendix. Since our hypotheses were all preregistered, we use one-sided tests.

Table 2 reports summary statistics of the survey data, for our two cohorts (pre and post Tiananmen). Note that on the pre-treatment variables (Age Enter College, Where Grow Up, and Gender), the two cohorts are almost identical. The only difference is that the post-Tiananmen cohort was almost a year older than the Tiananmen cohort when they began college. This difference is primarily the result of our sampling frame of college graduates in their forties. Some who were old enough to be in the Tiananmen cohort did not attend college until later in life, which leads to imbalance in our samples. Additional details are provided in the appendix. Post-treatment variables show modest differences that may reflect the impact of the Incident or simple lifecycle patterns. For instance, the older cohort has higher education levels and higher incomes.

Table 2 Summary Statistics

RESULTS

In this section, we present our data and results. For each of our dependent variables, we measure the impact of the democracy movement using simple difference of means tests, OLS regressions, and fuzzy RDD methods. For the t-tests, we vary the bandwidth around the discontinuity. For the fuzzy RDD, we examine lower and higher order polynomials in the first stage model. We will also separately examine respondents who attended highly politicized campuses and respondents who attended less politicized campuses.

To preview our findings, we find a strong and consistent effect of the movement on long-term attitudes. For nearly all our analyses, subjects who were in college during the democracy movement have higher democracy support scores and are more likely to define democracy intrinsically than subjects who started college after the end of the democracy movement. A deeper look into the data provides several secondary findings. First, the results are almost entirely driven by alumni of the most politicized universities, who make up less than a third of the sample. For this group, results are very strong, consistent, and statistically significant. For alumni of less-politicized campuses, there are very small effects that are almost never significant. Second, the results suggest that it was indeed direct exposure to the movement that affected attitudes, not broader changes in the political environment. Lastly, the movement's impact was primarily to reduce acceptance of performance-based legitimacy, as affected respondents are more likely to reject instrumental definitions of democracy and see the regime as significantly less democratic than post-Tiananmen respondents.

T-TEST RESULTS

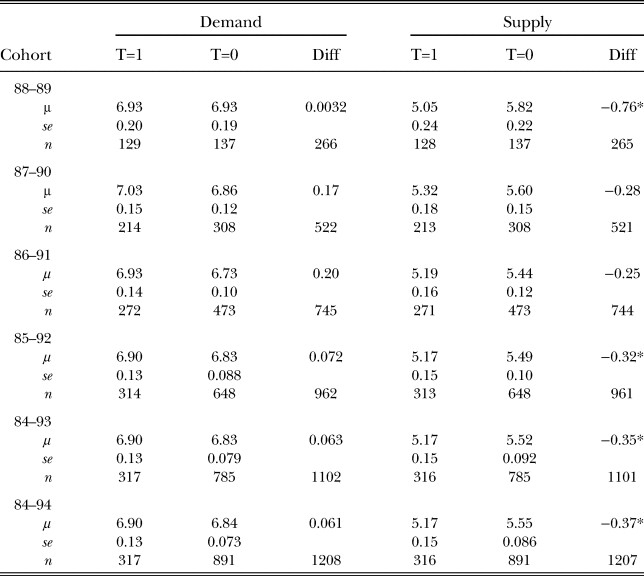

Table 3 shows the impact of the movement on attitudes, comparing attitudes for treatment and control for the Democratic Support and Intrinsic-Instrumental indices, and testing for significant differences. The rows of the table vary the enrollment cohorts from those who were freshmen in fall 1988 or 1989, to all students who began college between 1985 and 1994. Note first, for both indices and for all comparisons, means for treatment and for control groups are greater than zero, indicating that overall, there is support for increased democratization and there is a general sense that elections and civil liberties are more central components of democracy than are economic growth and income equality.

Table 3 Tiananmen Cohort Has Higher Democratic Support and Higher Intrinsic Understanding of Democracy

* .05; +.10

The Table shows difference of means T-tests comparing the Tiananmen cohorts' (T=1) and post-Tiananmen cohorts’ (T=0) Support for Democracy and Intrinsic versus Instrumental Characteristics of Democracy score. The dependent variables are presented in the two sets of columns. The row clusters refer to different subsets of the data. The narrowest comparison is between those who entered college in fall of 1988 and those who entered college in fall of 1989. The largest comparison (bottom row) includes students who began college between 1984 and 1994. Per preanalysis plan, tests are one-sided.

More importantly for this paper, there is a large and statistically significant difference between treatment and control groups for both indices in every comparison. Alumni who were in college during the Tiananmen Movement have a higher Democratic Support Score, indicating greater preference for increased democratization than alumni from the post-Tiananmen period. Similarly, alumni from the Tiananmen cohort also rate intrinsic features of democracy as more essential than do alumni who enrolled after Tiananmen. The impact of the movement is stable in size and is consistently significant across different bandwidths, even with the narrowest comparison of the 265 respondents who enrolled in fall 1988 or fall 1989, immediately before and after the movement. These differences are striking, especially since the survey was conducted 25 years after the movement.

Tables 4 and 5 repeat the t-tests, now looking at the components of each of the indices. Looking first at the variables in Democratic Support Score (Demand minus Supply, Table 4), note that mean Demand for Democracy is high for both treatment and control (nearly 7.0 on a 0–10 scale). In fact, almost 90 percent of both groups had mean Demand for Democracy scores above 5.0. Mean Supply of Democracy is considerably lower, about 5.5 for both groups, with about two out of three of respondents rating China's democracy at 5.0 or above, on a 0–10 scale. As found previously, there is general agreement that democracy is suitable for China, as well as recognition that China is not fully democratic.

Table 4 Difference of Means Tests for Democratic Demand and Supply

* .05; +.10

This table repeats the analysis from Table 3, but uses respondents’ Democratic Demand and Supply scores as dependent variables. Per preanalysis plan, tests are one-sided.

Table 5 Difference of Means Tests for Essential Characteristics of Democracy

* .05; +.10

This table repeats the analysis from Table 3, but uses respondents’ Essential Characteristics of Democracy agreement scores as dependent variables. Per preanalysis plan, tests are one-sided.

Examining the impact of the movement, the differences between treatment and control groups are consistent with our hypotheses for both variables, but are strongest for the Supply of Democracy, that is, respondents’ ratings of the current level of democracy in China. It appears that the patterns observed in the Democratic Support index are primarily driven by Supply of Democracy—the rating of how democratic China is currently. For this variable, alumni from the Tiananmen cohort consistently rate China as less democratic than does the post-Tiananmen cohort. For Demand for Democracy, there is always a positive difference between cohorts but it is never significant. The results suggest that both groups find democracy appealing and appropriate for China (hence the high average Demand score), but also that they may have different definitions of democracy. Thus, the Tiananmen cohort sees the regime as less democratic and the post-Tiananmen cohort sees the regime as more democratic.

Examining now the components of the Instrumental versus Intrinsic Characteristics of Democracy Index in Table 5, note first that Economic Growth and Civil Liberties have the highest mean agreement scores, with overall averages above 7.0 on a 0–10 scale. Political Rights are slightly lower than both of these, and Income Equality has the lowest agreement score. Interestingly, this indicates strongest support for a vision of democracy that provides economic growth and protection of individual rights, with slightly lower mean agreement that the election of leaders is a key feature of democracy, and substantially less support for income equality as a feature of democracy.

Comparing the Tiananmen and post-Tiananmen cohorts, differences are consistent with our hypotheses in almost every case, although less frequently significant. The strongest results are for the Political Rights variable, where the post-Tiananmen cohort has a lower “agree essential” score than the Tiananmen cohort for every comparison. The point estimate is fairly stable—between +.32 and +.47 for all bandwidths, on a 1–10 scale. These differences are significant for all but the narrowest and smallest comparison of those starting college in 1988 or 1989. This would seem appropriate, since elections were one of the central aims of the movement.

Income Equality and Economic Growth also follow the expected pattern: alumni from the Tiananmen era are less likely to identify these as essential characteristics of democracy. However, these differences are only rarely significant at the .05 level. Given the relative stability of the estimates, this may mean that the smaller bandwidths simply lack power to detect effects. Lastly, there is no evidence of a difference between the Tiananmen and post-Tiananmen cohorts in terms of Civil Liberties. The difference between groups is close to zero for all bandwidths, varies between positive and negative, and is never significant.

These simple t-tests suggest some preliminary conclusions. For both cohorts, there is a relatively high Demand for Democracy score—indicating that each group supports democracy in China. The critical difference, however, is in what “democracy” means to each cohort, and what sort of democracy each group wants. Looking at the responses regarding the essential characteristics of democracy, respondents who were exposed to the Tiananmen movement are more likely to identify election of leaders and less likely to identify economic growth or income equality, while respondents that only attended college after the movement are more likely to see economic performance as a feature of democracy. There is no evidence of any difference for Civil Liberties—but respondents from both cohorts had the highest mean agreement score for this variable: all respondents largely agreed that Civil Liberties are an essential characteristic of democracy. This reveals an important difference in priorities, as well as understandings of democracy, for these two groups.

MULTIVARIATE MODELS: OLS AND FUZZY REGRESSION DISCONTINUITY ANALYSES

We now consider results from a multivariate analysis, examining both OLS and fuzzy regression discontinuity design. Fuzzy regression discontinuity is appropriate when the forcing variable, in this case birth date, does not perfectly determine treatment assignment, but subjects are unable to manipulate their assignment (Lee and Card Reference Lee and Card2008; Lee and Lemieux Reference Lee and Lemieux2010). It is reasonable to believe students’ birthdates or ages have no impact on their political attitudes, at least within a small bandwidth of their birthdates. However, a small change in subjects’ birthdates may change their college entry years and consequently their participation in the 1989 movement.

Figure 1 shows the relationship between birthdate and treatment assignment. The x-axis reports birthdates in month/year bins. The y-axis reports the proportion in the Tiananmen cohort. Points in the graph are thus the proportion of subjects born in a particular month/year that were in college during the Tiananmen movement. The vertical line denotes the official enrollment deadline that should act as an exogenous threshold for assignment to be in college during, or after the movement. If assignment were perfect, all the proportions below September 1970 would be 1.0, and all the proportions above it would be 0.0. Clearly, assignment is not perfect. Some students started college later than a “normal” trajectory would predict. For example, a subject born in the fall of 1968 should have been a junior in college during the June Fourth Incident. Some did not start college until after the incident, however, implying that they did not attend college until several years after completing high school. This pattern is not as common on the right side of the cut-point, because there are naturally more “late bloomers” than “early bloomers”—only a few entered college younger than 18 years old, but a larger number of older students did not begin college until well after high school. In total, there are several hundred subjects in the control group that would have been in the treatment group if they had gone straight from high school to college on the standard schedule.Footnote 9

Figure 1 Birthdate predicts exposure to treatment

Note: Birthdates are categorized into months. Y-axis is the proportion of respondents born in each month that were in college in the spring of 1989 and were thus exposed to the democracy movement and aftermath. Vertical line is the September 1, 1970, cutoff for assignment to college in fall 1988 or earlier, or fall 1989 or later.

Trend line is kernal smoother.

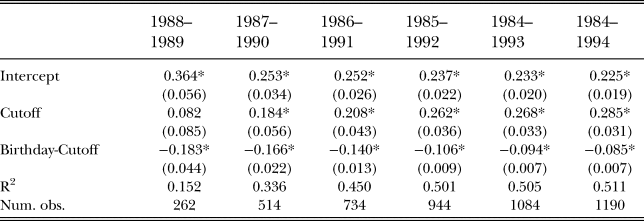

Table 6 shows results from first-stage models that predict assignment to treatment or control. In these regressions, the treatment condition, T, is predicted by two variables: the difference between students’ birthdates and the cut-point, and an indicator variable for whether the subject was born before the cut-point. The predictive strength of these models naturally varies across bandwidths. Predictive strength, measured with the R-squared, is lowest (.165) for the narrowest comparison window (September 1969 to September 1971) and largest for the entire dataset (:541). The larger bandwidths are easier to predict, especially for those born after the cutoff, because so few students started college younger than age 17.

Table 6 First Stage Model for Fuzzy RDD

* .05; +.10

Dependent variable is T, with T = 1 indicating exposure to the movement and T = 0 indicating a lack of exposure. Models with polynomials in appendix.

Table 7 presents comparisons of treatment effects estimated by OLS models and TSLS models for the two scales and their component variables. All of the cells show estimated effects of participation in the movement on attitudes. The rows correspond to the dependent variable and the columns correspond to the model used to estimate the coefficients. Control variables are not shown but include CCP membership, income, education, marital status, and employment, as specified in our preregistration. Full results are available in the appendix.

Table 7 Impact of Movement on Attitudes across Models, Instruments, and Covariates

* .05; +.10

Table shows estimated effect of college enrollment during the movement. Significance tests are one-sided following preregistration plan. Full results of each model are in the Appendix.

Entries show estimated coefficients and standard errors for T (indicator variable for participation in the movement). Rows correspond to the dependent variable and columns correspond to the model and controls used. Control variables included CCP membership, marital status, gender, income, and highest degree. Full results in supplemental materials.

As with the t-tests, there is consistent, though weaker, evidence of a difference between the Tiananmen and post-Tiananmen cohorts. Consider first the Intrinsic-Instrumental Scale. There is a significant difference between the Tiananmen and post-Tiananmen cohorts in every model, with and without covariates, using OLS and fuzzy regression discontinuity. The impact of exposure to the movement is positive, consistent with our expectations. The Democratic Support Scale, however, has the right sign but is only significant in an OLS model without controls.

Regarding the components of the scales, they have the expected sign in every model, but individually are only sometimes statistically different from zero. The only exception is the Political Rights variable; for that variable, the effect of the movement is very stable across all specifications (about .50 on a 0–10 scale) and the impact of the movement is always statistically significant.Footnote 10

These aggregate results show that there are differences between alumni who were exposed to the movement and those who were not, even after a quarter century. However, the inconsistent results pose new puzzles about which variables are significant and why. In addition, we must consider the question of whether it was indeed exposure to the movement, and not something else that affected attitudes. We will return to these questions after conducting several additional tests in the next section.

ARE DIFFERENCES DUE TO PARTICIPATION IN THE MOVEMENT OR TO THE CHANGES IN THE BROADER POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT?

We find significant differences between the Tiananmen and post-Tiananmen student cohorts, specifically higher Democratic Support and Intrinsic understandings of democracy for the Tiananmen cohort. Yet, as we noted above, there are at least two ways that the Incident could have affected attitudes. One possibility is that participation in and exposure to the student movement and crackdown affected attitudes. An alternative mechanism, however, would be through the broader changes in the Chinese political environment following the movement. After the suppression of the movement, the regime significantly tightened political control and ended a period gradual liberalization. Students who were in college during the movement were also in college during a period of greater freedom; those who began college in the fall of 1989 or later missed both the movement and the experience of attending college in the more open environment of the 1980s. Thus, the higher democracy scores for our treatment group may reflect exposure to the movement, exposure to a different political environment, or both. In either case, the movement was the cause, but the mechanisms at work would be different.

We cannot decisively differentiate between these two mechanisms, but we can offer suggestive evidence that exposure to the movement, not broader environmental differences, was the primary causal factor. We conduct two series of tests that rely on a simple proposition: more exposure to the treatment should increase the observed effect.

For the first test, if differences in exposure to the movement explains attitudinal outcomes, then greater exposure should result in larger effects. We thus test whether alumni from universities with greater exposure to the movement have larger treatment effects than alumni from universities where the movement was not as prominent.Footnote 11

Second, if differences in the broader political environment while in college explain attitudinal differences, then differences in exposure to that environment should also correlate with attitudes. We thus will test whether democratic attitudes correlate with enrollment year. Seniors in the spring of 1989 were finishing their fourth year of college in a relatively open environment; freshmen in the spring of 1989 were finishing their first year of college in that environment and had just one-fourth as much exposure to the campus environment of the 1980s. If the broader political environment explains attitudes, then within our treatment cohort we should observe a negative relationship between enrollment year and democratic attitudes.Footnote 12

As we will demonstrate below, we find a strong relationship between exposure to the movement and attitudes. The impact of the movement is large and significant for alumni of universities that were central to the movement but effectively zero for peripheral universities. For the second test, we find no relationship between level of exposure to the open environment of the 1980s and attitudes.

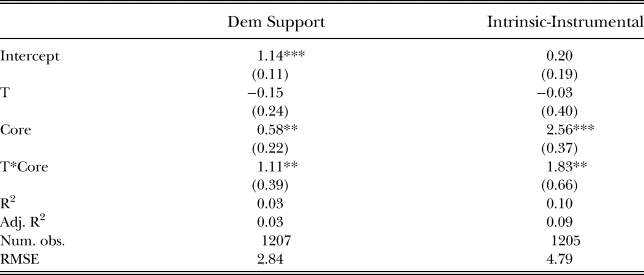

TREATMENT EFFECTS IN CORE VERSUS PERIPHERAL UNIVERSITIES

For the first test, we rely on qualitative accounts of the movement to identify universities that were highly involved in the movement versus those with less involvement. We then analyze alumni of these universities separately. Calhoun (Reference Calhoun1997) describes the “four core” universities as those that were most involved in the movement: Beijing Normal University, Tsinghua University, Peking University, and Renmin University. These elite universities in the Haidian District in Beijing were physically close to many movement activities, had widespread support for the class boycotts and protests, and contributed many of the movement's leaders. Other universities were farther from Tiananmen Square, were less politicized by the movement, and contained students who were less involved. If indeed it was the movement, not changes in the broader environment, that shaped attitudes, then we should see stronger treatment effects for the four core universities, and weaker effects for more peripheral universities. This is generally what we find. For three variables, the impact of the movement is much larger in core universities than in peripheral universities. For the other three, effect sizes are similar and smaller for both types of universities. In no case is there evidence that effects are larger in the peripheral universities.

Table 8 shows the impact of the movement on Democratic Support and on Intrinsic versus Instrumental understandings of democracy, separating alumni of core and peripheral universities and again using OLS and FRDD methods. The results are striking. For alumni of the core universities with the greatest involvement in the movement, we observe large and significant treatment effects in almost every model. For alumni from non-core universities, being in school during the movement never has a significant effect on attitudes. In addition, note that estimated effect sizes are much larger for the core group than the non-core group, and the non-core group often has the wrong sign for Democratic Support. These results are especially impressive given that there are more than twice as many respondents from non-core universities. There are only about 350 respondents from core universities, and less than 40 percent of these are in the treatment group. In contrast, there are over 800 respondents from the noncore universities.

Table 8 The Movement Primarily Affected Students at Core Universities

* .05; +.10

Table shows estimated effect of college enrollment during the movement. Significance tests are one-sided following preregistration plan. Full results of each model are in the Appendix.

We also test formally whether there is a significant difference between the impact of the movement for core and noncore universities. We use a simple OLS model with an interaction of the following form:

The difference in effects is captured by b3. Table 9 shows the results. For both Democratic Support and Intrinsic versus Instrumental Scales, b3 is significant and positive; there is a significant difference in the impact of the movement on core versus noncore alumni.

Table 9 Estimated Impact of the Movement is Larger for Alumni of Core Universities than for those of Peripheral Universities

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Combined, the implication is that respondents who attended universities where the movement was most active also show the greatest impact of the movement. Indeed, there is effectively no impact of the movement among alumni of the other peripheral universities. This suggests that the significant results we observed in the full sample analysis were in fact entirely driven by the 360 alumni of these four universities that were most central to the movement. Further, added to the fact that in peripheral universities there is no difference between the Tiananmen and post-Tiananmen cohorts, this is evidence that the movement's impact was primarily through direct exposure and participation, not indirectly through the changes in the broader political environment that it caused.

To further examine this possibility, we conduct one additional test. If the impact of the movement was indirect, by changing the broader environment, then we may again leverage exposure to that environment. Students who were finishing their senior year in spring of 1989 had four years of college in an environment of relative political freedom. Students who were finishing their freshman year had just one year of college in that environment. If indeed it was the broader environment that affected attitudes, then that environment should have left a stronger mark on students who experienced it for more time, the seniors. To examine this possibility, we test for a relationship between years of college completed by spring 1989 and attitudes, looking only at alumni in the Tiananmen cohort. We regress attitudes on years completed by spring 1989, for alumni from all, core, and peripheral universities. Table 10 shows results for these regressions on each of the dependent variables, for all, core, and peripheral university alumni.

Table 10 Relationship between Years in School and Dependent Variables, Tiananmen Cohort Only

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

In every case, there is effectively no relationship between year of college and attitudes. None of the coefficients are even marginally significant; all are very close to zero. More years of college in a relatively open era is not associated with more democratic attitudes. Again, this is partial evidence that the movement's impact was through direct exposure to and participation in the movement—not through broader socio-political changes. Yet, it is consistent with personal accounts of the movement, where former participants describe the movement as changing their lives, and identify specific moments of conflict with the regime that steeled their resolve.Footnote 13

Of course this evidence remains tentative because assignment to universities is not random, and it may be that there are systematic differences in students across universities that interacted with changes in the political environment. In our discussion, we will suggest future directions that might better test these two mechanisms.

CORE V NONCORE COMPONENT ANALYSIS

Finally, we examine the component variables of each of the indices, comparing the impact of the movement on alumni of core and peripheral universities. This comparison will clarify the differences between core and peripheral universities and will also shed light on why the movement had significant effects on some components and not others.

We again examine simple difference of means, OLS, and fuzzy regression discontinuity. The results are very similar, so we relegate the multivariate results to the appendix (see Tables A13 and A36) and focus our discussion on the simple difference of means comparisons. Table 11 examines the component variables of each index, comparing the impact of the movement for Core and Peripheral Universities. There are three general trends in the data.

Table 11 Responses by University Type and Movement Exposure

Table shows mean responses to each of the questions analyzed, by university type and by exposure to the movement, with standard errors in parentheses. Columns labeled “Movement” show averages for respondents who were in college during the movement; columns labeled “Control” show averages for respondents who attended college immediately after the movement. Significance tests are one-sided following preregistration plan.

First, there is no evidence that the movement had any impact on Demand for Democracy or Civil Liberties responses. In both cases, mean responses are quite high for all respondents and the difference between Tiananmen and post-Tiananmen cohorts is effectively zero. In other words, respondents of all types generally agree that China is suitable for democracy and largely agree that civil liberties are an essential characteristic of democracy.

However, the movement did affect other attitudes and understandings of democracy, but only for alumni of the four core universities. For these alumni, those in the Tiananmen cohort see China as significantly less democratic than do their colleagues from the post-Tiananmen cohort. They also have significantly lower mean scores for Economic Growth and Income Equality as essential features of democracy. In each case, these differences suggest a rejection of the regime's performance-based legitimacy claims. They see China as less democratic, and are more likely to understand democracy as procedural rather than based on economic performance. At the same time, for non-core universities, we find no evidence that the movement affected Supply, Economic Growth, or Income Equality attitudes.

Finally, there are suggestive results on Political Rights, that is, the centrality of elections in democracy. In the combined sample, the impact of the movement was approximately +.30 and significant, when split into two samples—with lower power, the effect sizes are stable, but no longer significant. Further, in the multivariate models (Tables A13—A36, in the appendix), there is a positive and significant impact of the movement on Political Rights attitudes for the non-core universities as well as a positive but insignificant result for the smaller sample of alumni from the core universities. We see this as suggestive evidence that the movement affected attitudes about political rights for respondents from both sets of universities, but the effect sizes are modest and thus undetectable in the lower-power subgroup analysis. Since elections was one of the movement's goals, this broader impact of the movement on attitudes about political rights across core and peripheral universities is consistent with previous work on social movements that found bystanders and participants adopting movement positions.

In the appendix, we address possible problems with our analysis, including sampling frame problems, whether the observed differences reflect participation in the movement or the regime's post-Tiananmen re-education efforts, self-selection into college post-Tiananmen, and other assumptions.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis finds a significant impact of the movement, both in terms of Democratic Support and in terms of our Intrinsic-Instrumental Index. Respondents exposed to the movement have higher mean Democratic Support scores, suggesting a preference for increased democratization. These respondents also have higher Intrinsic-Instrumental scores, indicating that they understand democracy more in terms of elections and liberties, rather than economic and redistributive performance. These findings echo research on the civil rights movement, showing long-term effects. Findings also show how even a failed movement in an authoritarian regime may affect long-term attitudes. More than a quarter century after the movement, the consistent results are striking.

These results, however, are largely the result of effects observed in alumni of the four core universities with the greatest exposure to the movement and its repression. Neither index reveals a Tiananmen effect when looking only at alumni from peripheral universities. Looking at the components of the index, we see three broader lessons.

First, there is no Tiananmen effect on Demand for Democracy or Civil Liberties. For each of these, mean scores were already very high for all subgroups. Regarding Demand for Democracy, our respondents uniformly support democracy for China—but as our other analyses reveal, they differ on what democracy means. Regarding Civil Liberties, we speculate that the personal costs of censorship and information control are borne by everyone in our sample—including limits on internet access, press censorship, and other restrictions on information. Our respondents are aware of the greater freedom of information enjoyed elsewhere in the world and their answers may reflect a desire for similar freedoms.

Second, for alumni of the core universities, we find that exposure to the movement affected Supply of Democracy, Economic Growth, and Income Equality. Specifically, these respondents see China as less democratic than do post-movement alumni, and they also are less likely to consider economic performance or redistribution as essential features of democracy. Interestingly, this implies a rejection of the regime's performance-based legitimacy claims. This implies that exposure to the movement and its aftermath left these alumni especially resistant to post-Tiananmen propaganda. Given how recent work on Hong Kong protests has found no impact of participation on attitudes, we suspect that our findings may reflect the extreme repression suffered by participants in the movement: the trauma of the repression may have left an enduring mark on participants’ attitudes.