Air pollution has troubled the Chinese population and environment since early industrialization in China.Footnote 1 It has become a potent social and political issue in contemporary China, not least in Chinese media given the heavy smog that has engulfed large areas in northern and eastern China in recent years. The nature, origins and seriousness of air pollution in China are now of grave concern to both urban and rural populations.Footnote 2 Media, politicians and Chinese citizens struggle to make sense of this issue and frequently rely on historical lessons and imageries to deal with the ensuing anxiety, fear and hope. Images of photochemical smog in Los Angeles in 1943, smog over the Ruhr in Germany in 1985, and other foreign places occasionally figure in Chinese media in conjunction with severe incidents of smog in China. Among these foreign incidents, the historical image of London as a fog city and, in particular, the London Great Smog disaster of 1952, is by far the most visible; it has been invoked most frequently in the Chinese press to conceptualize air pollution in China, in terms of the nature of pollution, the historical lessons to be learned, and the prospects for a solution.

London has been known as a city of fog in international media and in the British press from the middle of the 19th century, and in Chinese media since the 1870s. The historical image of a polluted city threatening the health of its citizens contrasts with the artistic portrayal of Victorian London engulfed in a mysterious, romantic and often poetic fog.Footnote 3 In China, London with its historical fog has, like no other polluted foreign city, become an icon of air pollution that has been mobilized by contemporary journalists to frame China's own pollution problem. In this article, we explore how Chinese media make sense of smog and air pollution in China through the lens of London's past. Specifically, we address the following questions: (1) How do Chinese news media relate London's past to China's present and establish an historical analogy to define, articulate and make sense of the smog issue in China? (2) To what extent is this related to and shaped by the early representations and collective memory of London as a fog city? (3) What is the difference between the news frames of smog established by official and commercialized media respectively? How does this foreign icon of air pollution offer arguments for official media to naturalize air pollution problems and for commercialized media to challenge their dominant narratives?

We first unwrap the images of London as a city of fog as presented in early Chinese media. Then we show how the Chinese press rediscovered the Great Smog of 1952 and invoked that incident, together with the general image of a foggy and polluted London, as a powerful, yet malleable, tool for discursive contestation on how to make sense of China's current air pollution problems. This contestation provides a fertile opportunity to examine Chinese media's framing of the smog issue and their hegemonic and counter-hegemonic practices. By studying the Chinese collective memory of London smog and its framing in contemporary media, we can better understand how the current discourse on air pollution in China is shaped both by history and collective memory and also by the media landscape in China.

Historical Analogy and Media Framing

It is common journalistic practice to report the present through an historical lens.Footnote 4 Journalists use history “to delimit an era, as a yardstick, for analogies, and for the shorthand explanations or lessons it can provide.”Footnote 5 The major categories of journalistic use of the public past include its use for media commemorations, to provide historical contexts, and as historical analogies, each of which has different implications for the development of the collective memory of the past as well as representation of the present. In terms of historical analogy, the shared meanings or collective memory of historical events, especially decisive or striking events that attracted extensive media attention when they took place, make them powerful tools in structuring media coverage of later events.Footnote 6 The analogies may lead journalists to assemble information in a particular manner and provide them with an independent perspective based on historical “lessons” to balance elite-dominated news frames.Footnote 7

News media's use of the public past in their reporting is a two-fold process of memory work. On the one hand, such use refreshes and strengthens the general public's collective memory of particular events. On the other hand, the symbolic potential and power of historical events depend upon the existing collective memory and its resonance with the elements of a society's underlying structure and culture.Footnote 8 In this article, we contend that the power of London to define the Chinese situation is due to Chinese people's collective memory of London as a fog city, which was the result of a century-long portrayal of London in many kinds of Chinese media platforms. These historical references become a discursive strategy for news media to make sense of controversial or emerging issues. An interpretation of and reflection on the past can help journalists define the present situation, identify the causes of events, convey a moral judgement on them, or provide historical lessons to be learned. In other words, invoking the past constitutes a “substantial frame,” which essentially “entails selecting and highlighting some facets of events or issues, and making connections among them so as to promote a particular interpretation, evaluation, and/or solution.”Footnote 9

Some historical analogies are mobilized by news media to introduce social change or challenge dominant ideology, but others tend to reinforce mainstream values or cultural themes.Footnote 10 Even for a single event, the multivocal nature of historical events can lead to a contestation of their meanings and implications. Such a contestation can take place between various social actors or interested parties like the government, activist groups and the general public.Footnote 11 It also manifests itself in different frames adopted by news media across the political spectrum, which become part of the media's exercise of hegemony and counter-hegemony.Footnote 12 As Yang has argued, “Chinese media is hegemonic but not without centrifugal or counter-hegemonic impulses.”Footnote 13 In this article, we focus on the contestation of frames of smog in different media outlets, arguing that Chinese mass media have bifurcated into official and commercialized media, each with its own ideological underpinning and relation to power structures.Footnote 14 More specifically, we focus on how and why Chinese media take up the foreign past of London's fog to make sense of the emerging issue of China's air pollution, and draw lessons and implications from such historical analogy in order to frame the smog issue in China in different ways.

As our analysis covers a period of some length, we have used different databases to locate our sources. First, we used the Shanghai-based Quanguo baokan suoyin 全国报刊索引 (Nationwide Index of Newspapers and Periodicals) database to search for items portraying London's fog in the pre-1949 era. Second, we used the full-text database of the People's Daily to locate news stories from 1949 to 2000 that mention London fog or the Great Smog. Third, we used the Chinese Core Newspapers Database to search for articles from 2000 to 2015 that mention London smog. In order to do an iterative reading and make a systematic comparison, we selected a number of official and commercialized newspapers for closer investigation. The official newspapers included the People's Daily (Renmin ribao人民日报), Xinhua Daily Telegraph (Xinhua meiri dianxun新华每日电讯) and Jiefang Daily (Jiefang ribao 解放日报). For commercialized newspapers and magazines we consulted The Beijing News (Xinjing bao 新京 报), China Business News (Caijing ribao 财经报), Twenty-First Century Business Herald (Ershiyi shiji jingji baodao 二十一世 纪经济报道), Qianjiang Evening News (Qianjiang wanbao 前将晚报), Chengdu Business Daily (Chengdu shangbao 程度尚报) and Sanlian Life Weekly (Sanlian shenghuo zhoukan 三联生活周刊). Last, we interviewed one Chinese journalist engaged in reporting on smog issues to support our interpretation of the media texts.

Early Imageries and Collective Memory of the Fog City

“London Fog” is a well-known brand name of a company started in 1923 that made rain gear,Footnote 15 but more importantly it has become a literary and artistic icon of Victorian London as a large metropolis plagued with moral debasement, pollution and unpleasant odours as a result of rapid urbanization and early industrialization. Historically, the English term “fog” has been used for both the humid and foggy climate of southern Britain and the polluted air in industrial cities such as London, Manchester and Leeds. The notoriety of Foggy London is depicted in European literature and art. Some of the most well-known examples of this are Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's (1859–1930) tales of Sherlock Holmes, Alfred Hitchcock's (1899–1980) silent film The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927), the novels of Charles Dickens, and the paintings of Claude Monet.Footnote 16 The popular image of London as the city of fog has also reached China through works like Lao She's (1899–1966) 1929 novel Mr. Ma and Son (Erma 二马) and Orphan in the City of Fog (Wudu gu'er 雾都孤儿), the Chinese translation of Dickens's Oliver Twist. Alongside the popular image of Chongqing as a city of fog, invoked since the 1930s, London still figures prominently as a foggy city in contemporary Chinese music, film, art and literature. According to a 1946 article in Shenbao, however, there is a key difference between the fogs in these two cities:

It is said that the fog in London is yellow, while fog in Chongqing has a clear white, milky appearance. This is presumably because there are many factories in London, wind mixes with smoke, and the fog turns heavy and yellow when blended with this smoke. Around Chongqing, on the other hand, there are mist-covered mountains and predominantly a green natural environment. That is why the fog there stays clear, light and faint.Footnote 17

Air quality in 19th-century London steadily decreased with increasing population and industrialization. The principal source of this air pollution – often referred to as London fog, London particular, London ivy or pea-souper – was smoke from coal combustion emitted from industrial smokestacks and traditional open coal fires in private homes, although by the end of the 19th century there was still no general agreement among scientists and politicians in Britain whether the foggy skies over London were caused by smoke from stacks and fires or by the humid, foggy, hazy air of southern England.Footnote 18

The two contrasting images of London were also represented in the burgeoning Chinese press in the 1870s: London as a city renowned for its humid and foggy climate (wu 雾 or dawu 大雾) and London as a city polluted by coal smoke (yan 烟, meiyan 煤烟 or yanwu 烟雾) as result of industrialization and open fires in private homes. The history, natural environment, political system and social conditions of London and Britain were introduced into Chinese works on foreign countries early on in publications like A Short Account of Maritime Circuits (Yinghuan zhilüe 瀛寰志略) (1848) by Xu Jiyu 徐继畬Footnote 19 and the 1852 edition of Illustrated Treatise on Maritime Countries (Haiguo tuzhi 海国图志).Footnote 20 But at most, they only briefly mentioned Britain's humid climate. The earliest report on London air in a Chinese periodical appeared in 1873 when the missionary newspaper The Church News (Jiaohui xinbao 教会新报) reported on three days of a “peculiar” fog (qiwu 奇雾) in London that stalled traffic and made it difficult for its residents to find their way around the city.Footnote 21 While this article did not establish the interconnection between fog and polluting smoke, an article in A Review of the Times (Wanguo gongbao 万国公报) in 1876 focused solely on the dense coal smoke from stacks in wintery London.Footnote 22 Incidents of heavy air pollution in London in the winters of 1880 and 1882 received no mention in Chinese newspapers, but in May 1891 A Review of the Times again reported on the poor air quality in London, specifically on what was referred to as “indoor fog.” Interestingly, the article reported on a solution that had been found to protect the sitting members of Parliament. The door to the Parliament chamber was sealed and outdoor air was led into the room through an iron pipe, the opening of which was covered with a cotton membrane to filter the incoming “foggy air” (wuqi 雾气).Footnote 23

The British debates on the source and potential solution to the smoke problems in London began to be taken up by the Chinese press at the turn of the century. In March 1899, an article in The Reformer China (Zhixinbao 知新报) addressed the problem of coal smoke in the city during the previous December, reporting that the smoke problem was caused by the high number of factory chimneys and the relatively high number of kitchen stoves in private homes.Footnote 24 Two years later, in November 1901, London again experienced a dense pea-souper, this time reported in News Digest (Xuanbao 选报). In this article the problem was described as “great fog”; pedestrians collided with each other and horse-cart drivers could not see their horses’ heads in front of them. The article focused on reduced visibility and problems of transportation and trade, but no mention was made of smoke and health problems.Footnote 25

It was only with a 1903 report entitled “The London Great Fog” in Journal of the New Citizen (Xinmin congbao 新民丛报) that these two dominant representations of London's air, fog and smoke, were brought together for the first time in the Chinese press. The article reported that a specialist from the British health authority had suggested that the smoke from all the factory chimneys in London be led into one large central chimney pipe where the smoke could be turned into soot and then electrically combusted. In the second part of the article, the humid climate with its “frequent fogs” (duowu 多雾) was introduced as the main reason why British women had such delicate, soft and beautiful skin.Footnote 26 So while the article reported on the two facets of London's air quality, it did not explicitly connect foggy London causally with polluting smoke from factories.

Unlike in China, the British debate gradually turned its attention to the interconnections between fog and smoke, and to health problems caused by air pollution. In the early British debates on London air, both “fog” and “smoke” were used to refer to polluted air. Already in the late 19th century, however, it was clear to experts, and gradually also to the public, that the pea-souper engulfing London during winter months was not simply humid fog, but polluted air that had palpable negative effects on human health and on the environment. Stephen Mosley explains that from the middle of the 1910s, more effort was put into monitoring air pollution, and abatement measures were taken in large British cities. His data show that by the mid-1930s, these measures to improve emissions from industry had borne fruit and the air in London and other cities had improved. They also show that emissions from private homes contributed substantially to the foul urban air in British cities during winter. Restrictions on private use of open fires were, however, not imposed, partly out of respect for individual freedom. It was only with the devastating experiences of the 1952 Great Smog in London that British authorities were able to win popular support for implementing restrictions on the use of traditional open fires in private homes. The implementation of the 1956 Clean Air Act finally reduced air pollution both from industrial and private sources in British cities.Footnote 27

Knowledge about the air quality in urban Britain was also increasing in China in the early 20th century. In October 1907, A Review of the Times provided the first detailed account in the Chinese press of the causes and effects of air pollution in London. According to the report, smoke containing sulphuric acid and soot particles was being emitted from stacks into the air and microscopic coal particles precipitated to the ground. Incomplete combustion of coal was not cost efficient, the report continued, and precipitating coal particles had serious negative effects on the physical environment and on human health. Londoners easily contracted respiratory diseases, and their lung tissues turned first grey, and then gradually purple, in contrast to rural dwellers whose lung tissues were white.Footnote 28 London as a city of fog, however, was never referenced by the author of this report when describing its polluted air.

Simultaneously with increasing Chinese knowledge about London air quality, the first article to link fog and air pollution causally in the Chinese press, however creatively, was published in The Ladies’ Journal (Funü zazhi 妇女杂志) in Shanghai in 1918. The author Huai Guichen 怀桂琛 categorized the fog of London using a colour scheme: white (bai 白) fog was pure and simple fog that became red (chi 赤) when the sun shone through it. When grey (hui 灰) fog descended, it was impossible to distinguish a person in the streets even though the sun was shining through it. Brown (he 褐) and black (hei 黑) fogs were the result of polluted air. Brown fog made it difficult, but not impossible, to find one's way around the city; your eyes turned “sandy,” your throat began to itch, and you could not stop coughing. In black fog, navigating the city was impossible, day turned into night, and the city transport system shut down.Footnote 29 This creative way of classifying grades of fog and polluted air to make better sense of the atmospheric conditions in London partially amalgamated the two interpretive frames for foggy and polluted London air. Huai's terminology was, however, not picked up in later Chinese media imageries of air quality.

These two separate frames of foggy and polluted London were also continued when the influential intellectual Liang Qichao 梁启超 (1873–1929) visited London in 1919. Arriving in the winter, he experienced first hand London's foggy weather and compared it to the depressed and dispirited British mentality. He referred to humid air but made no mention of air pollution.Footnote 30 After the First World War, images of London as a city of fog and pollution evaporated from the Chinese press for almost a decade and a half. When pictures and illustrations of foggy London reappeared in the Chinese press between 1933 and 1945, the heavy pea-souper in London winters was generally referred to as “fog,” “great fog” or “thick fog” (nongwu 浓雾), whereas concrete emissions of smoke were either “smoke” or “coal smoke.”

By the middle of the 20th century, “fog” was used as a generative term for both humid air and pollution/smog in representations of London. London fog had become a symbol for a densely populated and heavily industrialized city facing mounting health issues related to air pollution. By extension, in many magazine articles from 1935 to 1947, it had evolved into a symbol of a filthy city of social and cultural degradation, including high rates of crime and prostitution.Footnote 31 Among the two early frames used for London air, the “fog” frame came to dominate during the first half of the 20th century, representing a wide array of aspects of a defiled London. The study of early media reports makes it clear that as a result of the extensive representation of London in the early Chinese press, a dual collective memory of London had been formed: the classic image of a city of fog represented in art and literature, and a city of smoke, heavy pollution and human defilement. This multifaceted Chinese collective memory of the fog city remained latent until it returned to active Chinese memory as air pollution problems mounted in China in the 21st century. In this new iteration, however, it was the 1952 Great Smog in London that Chinese journalists drew on, as we shall see in the following.

Rediscovering the Great Smog

In 2010, the image of “the fog city of London” resurfaced in the Chinese media when smog and air pollution were emerging as a controversial public issue in China. In the process, the contrasting images from the early Chinese press converged and evolved into a new narrative centring on the 1952 London Great Smog. It was rediscovered and regularly circulated in Chinese media as an iconic event of air pollution, bringing together the historical context of global industrialization and the historical image of London as the fog city. As a result of the early images constructed by the Chinese popular press, the romantic and mysterious imagery associated with London as the fog city had embedded itself in China's collective memory. Contemporary news media's stories about London fog rely on such memory and tend to be based on the classic images presented in Monet's paintings, Dickens's novels or the stories about Sherlock Holmes. Due to the extensive early coverage of a fog city, these images are shared by Chinese journalists and their readers. As one journalist told us, for instance, his earliest knowledge of London fog came from the literary works he read in childhood (interview, 28 September 2016). The following excerpt from an article published in 2010 entitled “London: The Passing of the Fog City” illuminates this historical connection:

Most of those Sherlock Holmes fans who go to London with a novel in hand will be disappointed. Yes, Baker Street is still there. But the mystery of the clippity-clop on the street engulfed by the hazy mist (menglong de wu 朦胧的雾) has vanished without a trace. It seems that the impressive thick fog of London only exists in the literary history of the 19th century. Readers imagined the fog city for many years, but now they come to see the clear sky over the Thames.Footnote 32

From this excerpt, as in many others, an historical continuity between the earlier images and the contemporary coverage emerges. However, “fog city” is now the beginning of a new story, sometimes summarized in the phrase “taking off the ‘fog city’ hat.”Footnote 33 In the excerpt above, mist is still associated with mystery or romance. In other cases, however, fog is associated with serious air pollution. One newspaper article, for example, quotes Charles Dickens's vivid description of London fog and notes that such description “always reminds us of the Great Fog in 1952 that stifled London, on which day a thick yellow-green smoke-fog permeated the entire city.”Footnote 34 Another article points out that “Dickens did not see the darkest moment of the ‘fog city,’ the ‘toxic fog event’ (duwu shijian 毒雾事件) on 5 December 1952 that still makes London citizens shudder in retrospect.”Footnote 35

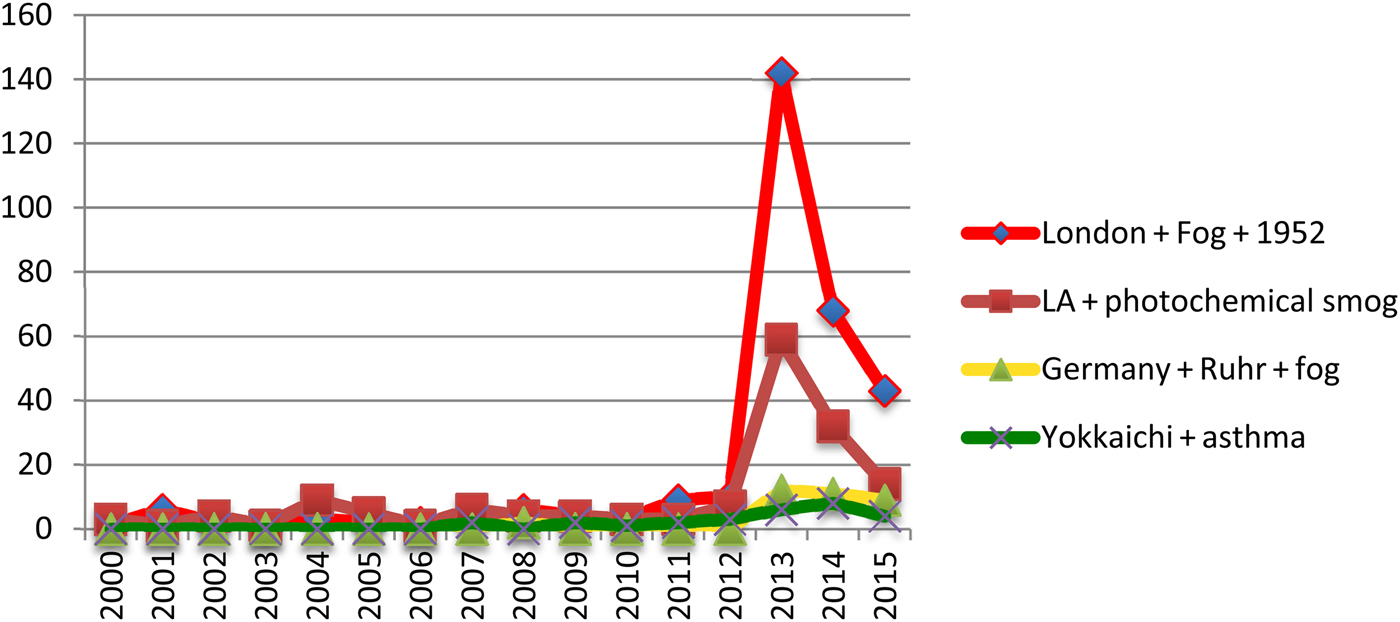

Interestingly, the horrors of the 1952 Great Smog were only rediscovered in light of China's own situation. At the time it happened, the Great Smog attracted no attention from news media in China. It only first appeared in an article introducing environmental science in People's Daily in 1978 and was mentioned only in passing four times in that newspaper in the years up until 2011. The Great Smog was seldom mentioned in Chinese newspapers from 2000 to 2012 (see Figure 1). Since then, however, it has emerged as the most dramatic episode in the new narrative about London fog and also as an iconic event of air pollution on a global scale. Now Chinese news media make extensive historical references to the Great Smog when they cover smog in China.

Figure 1: The Annual Distribution of Media References to Foreign Pollution Incidents (2000–2015), Chinese Core Newspapers Database

The rediscovery of the Great Smog is also manifested in the labels being used for London's fog. Before the 2010s, the Great Smog was mostly referred to as the “London Great Fog” (Lundun dawu 伦敦大雾), and only when smog became recognized as a serious environmental problem in China did other names begin appearing to describe this historical event: “poisonous fog” (duwu 毒雾), “smoky fog” (yanwu 烟雾), or “deadly smoky smog” (duoming yanmai 夺命烟霾). Compared to the contrasting images in the early Chinese press – fog versus smoke – contemporary media clearly emphasize the polluting aspect of a fog city.

To be sure, the Great Smog of 1952 has not been the only historical instance invoked by Chinese news media when covering smog issues. Other historical incidents of air pollution mentioned are the photochemical smog in Los Angeles in the 1940s and 1950s, smog in the Ruhr valley in Germany, air pollution in New York since 1950, and the high rates of Yokkaichi asthma between 1960 and 1972.Footnote 36 However, as Figure 1 indicates, the Great Smog is by far the most visible event of a foreign past being cited. It is mentioned in 304 articles, compared to 156 for Los Angeles, 34 for the Ruhr valley, and 29 for Yokkaichi. Among these articles, London appears in the title 34 times, Los Angeles only eight times. Moreover, compared to Los Angeles and other instances of air pollution, narratives about London or the Great Smog are made more compelling and powerful. This is largely due to the resilient collective memory of London as a fog city constructed historically by the media as described above.

The Great Smog has become the iconic event of air pollution in Chinese media. Pictures referencing the event and its aftermath, especially mist-laden landmarks in London and its citizens wearing masks, are widely used to represent this and other instances of air pollution. For instance, the cover image of the story “Six decades of global struggle against smog” in the Chin a Economic Weekly (Zhongguo jingji zhoukan 中国经济周刊, 10 February 2014), features the British model Julie Harrison wearing a facemask during the Great Smog, while an inside page shows a couple wearing masks while walking in London on 1 November 1953, almost one year after the Great Smog.

The Great Smog of 1952 has not only been rediscovered, repeatedly invoked, and highlighted, but it has also become the climax of the new narrative about a fog city. Detailed recollections of the Great Smog in Chinese media are frequently followed by a reference to the British government's abatement measures. Chinese news media present the British Clean Air Act as the direct result of the Great Smog. Some have argued that the air quality in London significantly improved in the early 1970s; others insist that it took much longer for London to regain a clear sky. For the majority of Chinese news media, however, London has won its war against smog.

Perceiving China through the Lens of London

Making an historical analogy

The story of the Great Smog is not told in its own right, but woven into a larger narrative about China's smog problem. First, London smog serves as a useful reporting tool for journalists. It directs their search for information or interviewing down a certain path. When questioning the vice-minister of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, for instance, a People's Daily reporter formulated her question about how to improve environmental law and policies in China by invoking the successful story of Britain's Clean Air Act following the Great Smog.Footnote 37 Second, news media have established an historical analogy between China's present and London's past. The most evident form of this analogy is the juxtaposition of parallel pictures taken in London in the 1950s and those taken in present-day China. Illustrating an interview carried by Oriental Outlook (Liaowang dongfang zhoukan 瞭望东方周刊, 26 December 2013), two press photographs – a police officer standing in thick fog in Beijing, taken on 10 January 2009, and a 1952 London police officer wearing a mask – appeared next to each other on the same page. Another article juxtaposed pictures of London and China showing women wearing masks with a background of railway stations or trains in smog to establish the historical parallel between China in 2013 and London in the 1950s. These pictures displayed similar visual elements: police officers, women, white masks, and most of all, hazy surroundings.

News media also employ indicators other than images of smog to illustrate the historical parallelism between London's past and China's present. An article in China Economic Weekly (10 February 2014) on how London has controlled its smog points out the striking similarities between the economic state of China in the 2010s and Britain in the 1950s in terms of GDP per capita, industrial structure, energy structure and major pollutants. The purpose of such an historical analogy is mainly to delineate the current situation in China and what lessons can be drawn from a foreign past.

The Great Smog is also invoked as a yardstick for the gravity of air pollution in China. A 2004 news story noted that the fog problem in China was alarming because “although the pollution of Beijing's fog is not as serious as the Great Smog in London and the photochemical smog in Los Angeles […], it has reached at least one quarter, if not half, of London's fog intensity in the 1950s.”Footnote 38 Ten years later, China's smog had become more serious than ever before, but interestingly official media still considered the Chinese smog problem to be less serious than London's. In the aftermath of an intense round of air pollution that hit northern China in January 2013, Xinhua News Agency, for instance, made the following observation:

People are concerned that if this grave environmental pollution continues it may lead to serious environmental problems in some megacities similar to what happened earlier in Europe and North America. One round of poisonous fog in 1952 in London caused 4,000 premature deaths and countless citizens suffered from breathing difficulties.Footnote 39

In other words, China has not reached the most devastating stage of air pollution.

By establishing such historical parallelism to China, the Great Smog in London serves as a useful reference for Chinese media to make sense of the situation in China. Different news media, however, invoke the collective memory of this foreign past and elaborate on its legacy differently. Official media outlets build a set of hegemonic narratives of the smog problem, while commercialized media try to establish alternative frames and challenge the official discourse on air pollution.

Dominant frames in official media

Smog poses serious environmental challenges to China, but in official media such as the People's Daily and Xinhua Daily Telegraph it is not considered unique to China. Rather, according to official media, it has also descended on other countries, especially advanced industrial countries:

Smog is one of the buzzwords for China in 2013. But it is not a problem unique to China. Whether it is the UK, the US, Japan and other developed countries that industrialized early, or Mexico, Iran, Mongolia and other developing countries, they have all previously encountered or are currently facing severe air pollution problems.Footnote 40

By grouping those countries into the categories of developing and developed countries, official media weave smog into a master narrative about development and regard it as an inevitable outcome of a particular phase of industrialization. As the Jiefang Daily put it, “the Great Smog in London and the photochemical smog in Los Angeles have revealed that smog accompanies certain stages of urbanization and industrialization; it is a universal problem when economic development reaches a certain level.”Footnote 41 The so-called “certain level” refers to “a high-speed economic growth phase,” that has caused for “almost all developed countries […] varying degrees of air pollution problems.”Footnote 42

According to official news media, all developed countries followed similar paths in their extensive efforts to fight air pollution, and China is no exception. The historical lesson from Western countries is frequently summarized by the government and official media as “develop first, become polluted, pollution control at last” (xian fazhan, hou wuran, zai zhili 先发展、后污染、再治理). It is obviously true that air pollution also occurs in other countries. However, the historical analogy highlights the similarities between China's present and foreign pasts but downplays the crucial difference between them, such as the causes of air pollution and its prevalence across the country. Such analogy, however, serves to naturalize China's smog problem by presenting it as the normal by-product of industrialization.

As smog is seen as a global problem and closely associated with economic development and industrialization, a related frame for official media is smog control as a long-term struggle. In an interview with the People's Daily, Wu Xiaoqing 吴晓青, the vice-minister of China's Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP), pointed out that “developed countries in Europe and North America were only able to solve most of their air pollution problems after thirty to fifty years. We need to treat the situation of air pollution in a correct way […] and prepare for a protracted war against it.”Footnote 43 Echoing Wu Xiaoqing's remarks, the title of a subsequent article carried by the People's Daily on 9 March 2014 was “Pollution control involves not only storming of heavily fortified positions but also protracted war.” In this way, official media mobilize iconic cases, including the Great Smog, to justify their positions:

“Diseases descend like mountains falling, but go away like reeling silk from cocoons.” Massive outbreaks of smog come about suddenly, but smog control cannot produce instant effects. This was true for Los Angeles and London that suffered from the “smog disease”; cities in China should wait patiently for “long-term treatment,” pay persistent attention, keep their feet on the ground, and thus finally escape from the ambushes of smog.Footnote 44

This excerpt uses the metaphor of disease to describe smog and emphasizes that there is no “quick remedy” (suxiaoyao 速效药). It uses Los Angeles and London as discursive tools to illustrate that smog control is a long-term struggle. The article devoted two paragraphs to retell the story of these two cities, arguing that it took London and Los Angeles thirty and fifty years respectively to fully improve their air quality. Some media even argue that although London's air quality has significantly improved, it is still the most polluted capital in Europe. The implication is, nevertheless, essentially the same: if China follows in the footsteps of those Western countries, it will take decades or even longer to finally solve air pollution problems.

As we have already noted, the fog city hat is no longer placed on London, and London now serves instead as an exemplar of how to deal with the smog problem. Titles like “Beijing can follow London's lead in smog control” and “Drawing on London's experience of fighting air pollution” are most illustrative. News stories and editorials also focus on the useful lessons that can be drawn from London. Most of them single out the Clear Air Act of 1956 and emphasize the importance of environmental legislation.

London also serves as a discursive device for Chinese national mobilization. An article carried by the People's Daily likened national mobilization efforts against air pollution to a game of chess involving all pieces in improving air quality.Footnote 45 According to official media, if China follows the example of London, “our smog days will become history as did the ‘poisonous fog’ of London”Footnote 46 and “London's today can be Beijing's tomorrow.”Footnote 47

By virtue of mobilizing the historical event of the Great Smog as an icon, the dominant frame used by official news media defines the Chinese situation hegemonically. The framing process echoes the official voices on air pollution. In effect, these frames have certain ideological implications. They justify the official stance and policies, and relieve the tension between public anxiety and government efforts by relating the foreign past to the Chinese present and pointing to a bright future.

Alternative frames and counter-hegemony

Commercialized, or more liberal, news media such as The Beijing News and Twenty-First Century Business Herald also frequently invoke the Great Smog and London, establish an historical analogy, and draw lessons from the past to make sense of the present. According to a journalist who works at a commercialized newspaper, everyone considers London as a “mirror,” a useful reference or lens for perceiving and reflecting on China (interview, 28 September 2016). As a framing tool, however, the meanings and implications of the foreign past are not fixed in commercialized media but are open to contestation. Such media contestation is concerned with how to interpret the past, what the terms “Great Smog” and “fog city” stand for, and what London's legacy for contemporary China is.

First, when mobilizing the Great Smog as a yardstick, commercialized media are more likely to point out that China's smog problem is very serious, even compared to the Great Smog. During several rounds of smog that finally led to the first-ever red alert in early December 2015, some media noted that “the hourly density of PM2.5 on 30 November reached as high as 1,000 micrograms per cubic meter, which was quite close to the ‘killer smog’ (sharen yanwu 杀人烟雾) that hit London half a century ago.”Footnote 48 Other commercialized media outlets have pointed out, by quoting scientists, that smog in China is more pervasive than in London and Los Angeles.Footnote 49 They also used the Great Smog to illustrate the possible health consequences of air pollution. One news article compared the density of particulates in Beijing and in London and vaguely discussed the effects of poor air quality on lungs, and then pointed out that the “terrifying smog” in London led to 12,000 premature deaths.Footnote 50 In this story, the discussion of the Great Smog served as a politically safe reference point by implying the possible consequences of smog. The article referred only to historical facts about a disaster that took place in London, rather than engaging in an outright, and potentially more sensitive, discussion of air pollution in China.

Second, in contrast to the general perception of London as a success story, some commercialized media tend to emphasize aspects of its failure. As early as 2008, a front-page story carried by Southern Weekly (Nanfang zhoumo 南方周末) warned that China should take “strict precautions against repeating the ‘fog city’ disaster (jienan 劫难),” i.e. the Great Smog.Footnote 51 At times, it is perceived as a disaster or tragedy that should not be repeated by China:

In the winter of 2013–2014, many Chinese cities encountered smog problems and the air quality deteriorated. This is not a short-term, seasonal phenomenon, but the outcome of long-term social structures. […] We should not act like London and remain inactive until 4,000 people die in one round of great fog.Footnote 52

This is not to say that official news media would regard the Great Smog as something to be repeated. But the difference lies in the temporal focus of the historical analogy. The stories carried by official media tend to be prospective, focusing more on what happened after the Great Smog; commercialized news media are more likely to be retrospective, paying more attention to the historical mistakes made leading up to the Great Smog. In a word, for official media, London's today could be China's future, but for commercialized media, China's future could be London's past.

Accordingly, in addition to useful lessons to be drawn from London's effort to control pollution, commercialized media also point to historical mistakes that should be avoided:

The smog turned into a killer that shocked the world on 4 December 1952. […] After that, the British government re-examined its previous economic development model, which was no different from chronic suicide. […] This historical mistake reminds us that trading overconsumption of natural resources for rapid increase of economic indicators is not a wise move. […] Only by bidding farewell to the blind worship of GDP … can we re-embrace the blue sky.Footnote 53

By pointing out that smog is the consequence of a suicidal development path rather than a normal outcome of industrialization, this excerpt takes a more critical stance towards the government and its development model; it also recommends a more radical policy that poses a direct challenge to the hegemonic discourse on air pollution and economic development constructed by the official media.

Last but not least, commercialized media also challenge the very way that the historical analogy is invoked by authorities and official media. This is most evident in their critique of vice-minister Wu Xiaoqing's remarks of a “protracted war.” Several editorials and op-ed pieces took issue with Wu's suggestion of a timeline of thirty to fifty years inspired by the Western experience. Commercialized media, acknowledging that it took thirty to fifty years for developed countries to solve their pollution problems, do not concede that China also needs to take that much time. The following paragraph is illuminating:

In the UK half a century ago, people lost their lives and left bitter lessons for the world. The failed path that developed countries have gone through should not be the only path for China today. What's more, it should not become an excuse when we fail or reasons for prevarication when we do not act.Footnote 54

This opinion piece is arguably the most critical; its author was dissatisfied with “the authorities’ stance being far from the public's expectations” (interview, 28 September 2016). Clearly, journalists from commercialized media believe it is unfair to “bracket together today's Beijing and yesterday's London”Footnote 55 because China now has the latecomer advantage. Drawing on historical lessons, they insist that China does not have to repeat all the “mistakes” made by developed countries. As one commentator ironically noted, “London back then had to ‘cross the river by touching the stones,’ but now we have a bridge over the river, why still plunge into the water?”Footnote 56 More important, commercialized media criticize authorities and the official media for exploiting London as an excuse for inaction. This is not only a challenge to the dominant frame in official media of a protracted war, but also a critique on the government's determination and efforts, as one title illustrates, “Don't kick the ball of pollution control thirty or fifty years into the future.”Footnote 57

Conclusion

In this article, we have investigated how Chinese media make sense of air pollution through the lens of London's past. As our analysis shows, news media established an historical link between London and China. The rediscovery of the Great Smog and its contemporary circulation in Chinese news media is deeply rooted in popular images and the collective memory of London as a fog city. The early images of this fog city constructed by the Chinese press, beginning in the 1870s, have had a significant impact on the Chinese popular imagination and consciousness, far greater than images of other polluted areas like Los Angeles and the Ruhr valley.

London has become a convenient reference point and serves a number of discursive functions as journalists make sense of China's problems. By invoking this powerful symbol and positioning China's smog in a cluster with other incidents of pollution, contemporary official news media justify a state-initiated plan of pollution prevention and control. The most significant ideological implication of such discursive practice is to naturalize the smog problem. The dominant frames in official media, however, are challenged by commercialized media. By employing alternative imageries of London's fog, they reveal London not only as a bitter lesson to be learned, but also criticize authorities for using London as an excuse for inaction and call for more effective pollution control.

The findings have theoretical implications for the study of historical analogy and news media's memory work. We have examined not only the contemporary return of an icon, but also the historical imagery and reinvention of that particular icon. Through its invocation, the depiction of the storyline of the past evolved from London as a fog city in a general sense to the 1952 Great Smog, an event that was debated and contested in the media. Our study also furthers an understanding of media framing and the practices of hegemony and counter-hegemony with clear differences between official and commercialized media. As media coverage of smog has been shaped by history, memory, and public imagination, historical analogy serves as a powerful tool for media framing. This became more evident when smog abruptly entered the Chinese public view in 2013 and authorities and journalists were in dire need of a framing device to make sense of the emerging issue.

Acknowledgement

Research for this article and the Airborne project was generously supported by the Research Council of Norway and the Centre for Advanced Studies, Norway.

Biographical notes

Hongtao Li is an associate professor in the Department of Journalism & Communication at Zhejiang University, China. His research interests include media sociology, collective memory, and environmental politics.

Rune Svarverud is professor of China studies at the Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, University of Oslo, Norway. His main research interests are ancient and early modern Chinese intellectual history, the history of science in China, and the cultural and linguistic encounters between China and the West post-1840.