1. Introduction

Rituals for “opening” water courses, i.e. ritually consecrating them and allowing their waters to begin flowing in them (at least ritually),Footnote 1 are known from several sources.Footnote 2 One of these sources, K.2727+K.6213, although cited in several publications,Footnote 3 does not have a modern edition. The present article presents an edition of this text and discusses it together with the other sources related to this ritual. All the sources discussed here show some similar features, such as the specialist involved, the ritual materials used, and the deities involved in the ritual.

2. The ritual for opening the canal K.2727+

The one-column fragment K.2727+K.6213, from Nineveh, preserves 21 lines of a ritual for the opening of a canal. The reverse is broken, and the obverse should have originally contained at least twice as many lines. The ritual was most probably to be performed by the āšipu priest. A copy of the tablet by W.G. Lambert was recently published by George/Taniguchi (Reference George and Taniguchi2021: no. 451).Footnote 4

The beginning of the ritual instructions described in the text are not preserved, but when the preserved text begins, the act of piling up ingredients, including plants, metals, and precious stones on “those soils” (ep(e)rī) is described, most probably referring to the piles of earth and silt dug out of the canal. In addition, figurines of turtles are placed on these earth-piles, presented as a gift to Ea. Then, three silver discs are produced, dedicated as a gift, and sent into the river to the gods Mummu, Qingu and Ešret-nabnīssu. Following this, as in other purification rituals, an agubbû water vessel is prepared. It is set at the head of the canal (for this term see note on l. 8’), and various plants, reeds, stones (mostly identical to the stones used earlier on the earth piles), and liquids are thrown into it. The text probably moves to the location in which the excavations took place (probably near the piles of earth mentioned earlier), where heaps of flour and dates, mirsu dishes, a libation vessel, a juniper censer, and a sheep offering are presented to Mummu, Qingu and Ešret-nabnīssu, and the names of these deities are invoked. The text then shifts again to Ea, prescribing a recitation to him, probably an incantation,Footnote 5 the text of which breaks off in the middle.

Transliteration

-

1’[ĝiš]⸢šinig ⸢ú?⸣[tuḫ-lam ĝišgišimmar.tur](?)

-

2’[gi.šul.ḫ]i(?) [k]ù.babbar kù.gi urudu ⸢an.na a?⸣.[gar5? na4gug](?)

-

3’[na4za.gìn na4nír](?) ⸢na4⸣muš.gír na4babbar.dili na4babbar.[min5] i[a 4-ni-bu(?) ]

-

4’[ana] ⸢ugu saḫarḫi.a⸣ šu-nu-ti dub-ak-ma bal.giku6 n[íĝ.b]ún.na⸢ku6⸣ [tam-šil bi x x](?)

-

5’[(0) š]á kù.babbar u kù.gi dù-uš-ma ki saḫarḫi.a šu-nu-ti ĝar-an šu-bu-ul-tú ⸢ana dé-a⸣

-

6’[(0) t]u-šeb-bé-el 3 aš.me kù.gi šá 1 gín.ta.àm dù-uš-ma níĝ.ba ĝar-an

-

7’[(0)] ⸢ana ?⸣ dúmun dqin-gi u deš-ret-nab-ni-is-su ana íd tu-šeb-bé-el

-

8’[(0) in]a ká íd a.gúb.ba gin-an ana šà a.⸢gúb⸣.ba ĝiššinig útuḫ-lam ĝišgišimmar.tur

-

9’[(0) gi.š]ul.ḫi kù.babbar kù.gi urudu an.na a.⸢gar5 na4⸣gug na4za.gìn na4nír na4muš.gír

-

10’[na4babbar.dili na4]⸢babbar⸣.min5 ia 4-ni-bu ĝiš.⸢búr⸣ làl ì.nun.na ana šà šub-di a-šar ḫi-ru-tú ḫe-ra-tú

-

11’[ana dúmun dqin-g]i u deš-ret-nab-ni-is-su 3 gi.du8meš tara-kás

-

12’[3(?) šuku 12(?).ta.àm ninda.zíz.à]m(?) ⸢ĝar⸣-an zú.lum.ma zì.eša dub-aq

-

13’[ninda.ì.dé.a làl ì].⸢nun⸣.na ĝar-an duga.da.gur5 gin-an níĝ.na šim.li ĝar-an

-

14’[udu.sískur ba]l-qí uzuzag uzume.ḫé uzu ka.ne tu-ṭaḫ-ḫa kaš bal-qí

-

15’[níĝ.na šim.l]i(?) ⸢dub⸣-aq mu dúmun dqin-gi u deš-ret-nab-ni-is-su mu-ár kam du11.ga

--------------------------------------

-

16’[én(?) dé]-⸢a⸣ lugal abzu muš-te-šir kal mim-ma šum-šú e-piš uru u é at-t[a-ma]

-

17’[šīmātu šá]-a-mu ĝiš.ḫurmeš uṣ-ṣ[u]-⸢ru⸣ šá šuii-k[a-ma]

-

18’[x x] ⸢x⸣ šu-pu íd sa-ki-ik-tú ḫe-ru-ú a⸢meš?⸣ ⸢nu ?⸣-[uḫ ?-š]á ? kun-⸢ni ?⸣ [x x (x)]

-

19’[x x (x) u]ṭ ?-ṭe-ti-šu šu-pu ina a.gàr ḫar-bu-[ti] ⸢x x⸣ [x x (x)]

-

20’[x x (x)] ⸢x lú.apinmeš⸣ qer-bé-e-tu 4 šá-s[u-ú ]

-

21’[ ] ⸢x x x⸣ [ ]

Rest broken

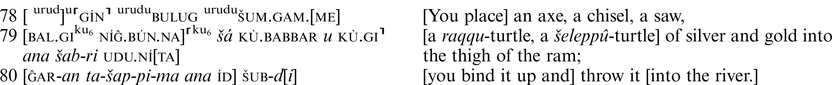

Translation

-

1’[ ] 4’You heap up 1’[t]amarisk, [tuḫlu-plant, young date palm](?)

-

2’[šalālu-ree]d(?),] silver, gold, copper, tin, l[ead, carnelian](?),

-

3’[lapis lazuli, ḫulālu-stone](?), muššāru-stone, pappardilû-stone, pappar[minu]-stone, y[ānibu-shell(?) (…)],

-

4’[up]on these earth-piles, and you make a raqqu-turtle, a šeleppû-turtle, [the likeness of(?) …]

-

5’[o]f silver and gold, and you place (them) with these earth-piles. 6’You send them 5’(as) a gift for Ea.

-

6’You make three gold sun-disks of one shekel each, and you offer (them) (as) a gift.

-

7’You send (them) to the canal [f]or Mummu, Qingu and Ešret-nabnīssu.

-

8’[A]t the “gate” of the canal you set up a libation vessel (agubbû). 10’You throw 8’into the midst of the libation vessel: tamarisk, tuḫlu-plant, young date palm,

-

9’[šalālu-ree]d, silver, gold, copper, tin, lead, carnelian, lapis lazuli, ḫulālu-stone, muššāru-stone,

-

10’[pappardilû-stone](?), papparminu-stone, yānibu-shell, iṣ pišri-plant, syrup, ghee. Where the ditch is dug

-

11’you prepare three portable altars [for Mummu, Qing]u and Ešret-nabnīssu,

-

12’you place [three(?) rations of twelve emmer breads each](?), you scatter dates (and) fine flour (sasqû),

-

13’you place [mirsu-dishes (with) syrup and bu]tter, you set up a libation vessel, you place a censer of juniper,

-

14'[you off]er [a niqû offering], you present the shoulder, fat, (and) roasted meat, you pour beer,

-

15'you sprinkle [the censer (with) juniper](?), you call the names of Mummu, Qingu and Ešret-nabnīssu. Thus you say:

---------------------------------------

-

16'[Incantation(?). E]a, king of the Abzu, who puts in order all that is named, creator of city and House are you!

-

17'To decree [the fates], to pl[an] the plans, is in (lit. of) your hands!

-

18'To make the […] appear, to dig the silted-up canal, to establish waters of abundance [forever](?),

-

19'To make appear the […] of its grain(?), in a waste field […]

-

20'[…] to ca[ll] the land [for](?) the cultivators,

-

21'[ ] … [ ]

Rest broken

Notes

-

1’–3’.The restorations follow the materials listed in lines 8’–10’. We thank an anonymous reviewer for the reading and restoration in line 1’, the beginning of line 2’, and the end of line 3’. The space in the beginning of line 2’ is admittedly quite wide for the restoration of gi.šul.ḫi, and therefore the restoration here is uncertain. At the end of line 3’ there seems to be more space, perhaps alternatively it is also possible to restore n[a4meš ni-siq-ti] according to the list of stones in the Bavian inscription of Sennacherib (see below § 3).

-

4’.The end of the line is restored according to the corresponding line in the Bavian inscription of Sennacherib (see below), although the end of the second word is broken there as well (the restoration pí-[ti-iq], for which see RINAP 3/2, 211, 309, was questioned by Frahm Reference Frahm1997: 153–154, and would not agree with šá in the next line of our text, if the two texts were indeed identical).

-

8’.For ká íd, Akkadian bāb nāri, as “gate of the canal” (“Kanaltor”) see Bagg Reference Bagg2000: 221. This expression is also attested in SpTU 1, 6 and in BM 54952 (see below § 3). The plant tuḫlu, which is quite rarely attested, should be identical to the plants maštakal and tullal, see Maul Reference Maul1994: 63 n. 42.

-

10’.The expression ašar ḫirûtu ḫerâtu (stative form with the subjunctive -u that may occur after the feminine -at after the Old Babylonian period, GAG §83a, cf. AHw, 348a) creates an alliterative effect. The use of ḫirûtu and the verb ḫerû here is related to the noun ḫarru, a quite rare Neo-Assyrian term for “canal,” see Bagg Reference Bagg2000: 160 n. 352, 273, for ḫarru as “Hauptkanal” see also p. 367. The expression in our line possibly implies a change of ritual place, from the earth-piles to the actual digging place of the canal. However, all ritual actions could have eventually taken place also at the “gate” of the canal, where the digging work started.

-

12'.In the beginning of the line it is possible to restore other variants of this phrase, perhaps omitting šuku or ninda.zíz.àm, and with different numbers; the restored [à]m can also belong to the phrase [ta.à]m, which occurs sometimes at the end of the phrase; see Maul Reference Maul1994: 50-51 with references in nn. 34 and 36 (we thank the anonymous reviewer of the article for the suggestions regarding the restoration).

3. The ritual for opening the canal: the āšipu and kalû priests

Although not explicitly indicated by the text, the ritual for opening the canal K.2727+ was most likely performed by the āšipu. This is evincible by other sources for this type of ritual. However, some of these texts relate to the kalû priest, some to the āšipu priest, and some to the king. These will be briefly discussed here. These sources include a passage describing a canal ritual from the Bavian inscription of Sennacherib, an inscription of the Kassite king Kaštiliaš digging the Sumundar canal using a silver spade and basket (Abraham/Gabbay Reference Abraham and Gabbay2013), K.2727+ edited above, the Namburbi catalogue SpTU 1, 6, the incantation SpTU 2, 5, and the ritual preserved in BM 45952. Some of these sources share similar features, such as the use of stones, figurines of turtles, the mention of ceremonial spades and baskets, and similar groups of gods related to the ritual (see §4 below).

The Bavian inscription of Sennacherib describes a ritual for the initiation of a new watercourse, where both a kalû and an āšipu priest performed the ritual. Some of the details in this passage correspond to the details found in the other sources for the ritual for opening a canal. Below is a transliteration and translation of the relevant passage (Sennacherib 156:r.6'–10' // 223:27–30 [Bavian inscription], see RINAP 3/2, 211, 315):

a-na pa-te-e íd šu-a-tu lú.maš.maš lú.gala ú-ma-ʾe-er-ma ú-šat-[…] na4gug na4za.gìn na4muš.gír na4nír na4babbar.dilimeš na4meš ni-siq-ti bal.giku6 níĝ.bún.naku6 tam-šil bi-[x x]Footnote 6 kù.babbar kù.gi šim.ḫi.a ì.giš dùg.ga a-na dé-a en nag-bi kup-pi ù ta-⸢ma ?-mi ?⸣-ti den-bi-lu-lu gú.gal ídmeš den-e-im-du en ⸢e⸣ u ? pa5 ú-qa-a-a-iš qí-šá-a-ti a-na dingirmeš galmeš ut-nin-ma su-up-pi-ia iš-mu-ma ú-še-ši-ru li-pit šuii-ia

In order to open that canal, I sent an āšipu (and) a kalû and … … […] carnelian, lapis lazuli, muššāru-stone, ḫulālu-stone, pappardilû-stones, precious stones, a raqqu-turtle, a šeleppû-turtle, the likeness of … [of] silver (and) gold, aromatics, (and) fine oil, I gave as gifts to Ea, the lord of underground waters, cisterns, and…, (to) the god Enbilulu, the inspector of canals, (and to) the god Enʾeʾimdu, the lord of [dike(s) and channel(s)]. I prayed to the great gods; they heeded my supplications and made my handiwork flow.Footnote 7

Does this mean that generally the ritual was indeed performed by the two specialists, each complementing the other, or does this mean that each of them could perform the ritual separately and that usually simply the availability of one of them, or the choice of the political functionary initiating the canal, determined which of the two would perform the ritual? Perhaps the Sennacherib text, where a special monumental waterway was initiated, is a special and unique occasion, and therefore an ideal reality of two priests working together was chosen (in reality or in the text), while more commonly such initiations were only performed by one of them?

It is difficult to answer these questions, but it should be noted that similar questions arise for other rituals as well, such as building rituals and initiation rituals for the divine image (Ambos Reference Ambos2004: 18–20). In these cases, we sometimes find similar ritual texts, some directed to the āšipu, and others to the kalû, sometimes with some overlap or with the appearance of one of these specialists in the ritual of the other specialist, at times with a change of the grammatical deixis between second and third persons (Ambos Reference Ambos2004: 18). The juxtaposition of the āšipu and kalû priests in certain ritual occasions is also documented in some Neo-Assyrian letters, raising similar questions.Footnote 8

The verbal repertoires of the āšipu and kalû priests were different: The āšipu's utterances (mostly incantations) usually address the specific ritual context and the materials used in it and are generally concerned with the removal of different kinds of evil for this goal. The kalû's utterances (mostly Emesal prayers) deal with the general notions of divine manifestation and abandonment and are aimed at divine pacification. In the ritual for opening a canal, the duty of the āšipu was to use the ritual materials to “physically open” the canal (spade and basket) and recite incantations to keep the evil away by addressing the netherworld forces (K.2727+ and SpTU 2, 5:59–61). The duty of the kalû was to recite Balaĝ and Eršema prayers probably in order to pacify the gods at the sensitive moment of the ritual opening (BM 54952).

As will be discussed below, opening a canal implies opening a channel between the groundwater of the Apsû and the water on earth, which implies the participation of both the netherworld and ancestral gods. The perceived risk (especially by non-ritual sources) was probably to awaken both evil beings and anger the gods, therefore some clients (like Sennacherib) probably wanted to protect this sensitive moment from any possible evil influences. Thus, they appointed both an āšipu and a kalû. We should keep in mind that this was at least the theoretical overlap in some sources, like the Bavian inscription. However, it remains unclear whether this was the case in all sources, and if this ritual was actually carried out by one or two specialists at the same time.

The ritual of the āšipu priest

As previously said, K.2727+ was most probably performed by the āšipu priest. The ritual, incantation and Namburbi catalogue SpTU 1, 6 provides an important support for this argument. It lists the following three incipits related to the ritual for opening a canal (left edge 1’–3’) (see Maul Reference Maul1994: 194 with nn. 332–333):

The first incipit cannot be identified. The third incipit, as identified by Maul (Reference Maul1994: 194, n. 333), corresponds to the incantation SpTU 2, 5 (see below). The second incipit is identical to the incipit of BM 54952 (// catchline of BM 46548, see below), but as noted by Maul (Reference Maul1994: 194, n. 332), it may also correspond to K.2727+ edited here (perhaps implying that K.2727+ had a similar incipit). This raises several possibilities: (1) There were two different (but similar) ritual texts with the same incipit, one for the kalû (BM 54952) and one for the āšipu (K.2727+). (2) K.2727+ is actually not an āšipu ritual (and accordingly én should perhaps not be restored in line 16’), but part of the same kalû ritual as BM 54952 (i.e. containing both Emesal recitations and an Akkadian recitation). (3) K.2727+ and BM 54952 contain the same ritual, and there was one ritual text which included instructions both related to the kalû and the āšipu (this would be a rare phenomenon in the Neo-Assyrian period). (4) K.2727+ did not begin with the incipit e-nu-ma ká íd i-pat-tu-u but rather with the first incipit cited above (e-nu-ma lú íd gibil), while the second incipit in the catalogue related to the kalû ritual BM 54952 (although listed in an āšipūtu catalogue).

We assume, although not with certainty, that option 1 is the case here, meaning that there were two different texts with an identical incipit, one for the āšipu and one for the kalû, even if this cannot be confirmed.Footnote 9 Although no specialist is clearly mentioned in K.2727+, the incipit in l. 16’ probably refers to an incantation, indicating that it belonged to the āšipu's repertoire. Specifically, since it is mentioned in a catalogue of Namburbi rituals, and since the ritual actions and ingredients listed in it resemble those in such rituals (compare Maul Reference Maul1994: 41–46), it may have been part of a Namburbi ritual, used to overcome the impurity and malevolent omens that may arise from digging a new canal (compare Ambos Reference Ambos2004: 35 with n. 250). Furthermore, the ritual instructions in lines 1’–15’ resemble those of SpTU 2, 5 (see below), where an āšipu is clearly involved.

As noted above, the Sumerian incipit mentioned in the Namburbi catalogue SpTU 1, 6 can be identified with the bilingual incantation SpTU 2, 5 (// TIM 9, 29 // Collection S. Preston), followed by a short passage with ritual instructions. This incantation represents the best piece of evidence for assigning K.2727+ to the āšipu's repertoire: first, SpTU 2, 5 clearly belongs to the āšipu's repertoire, since it begins with the incipit én and bears the rubric ka-inim-ma íd ka ĝál-tak4-a-ke4 “It is the wording for opening the mouth of a canal”; second, it shares several features with K.2727+. SpTU 2, 5 deals with the divine purity of a canal, noting that its earth (eperū, Sum. saḫar) was removed with tools of precious metals and stones (lines 12–13), and its waters filled by the deities Enki (Ea), Iškur (Adad), Enbilulu, Ninazu, Enkimdu, and Šakkan (lines 14–23). Then, the incantation notes that Asalluḫi purified the river with various materials (this purification probably reflecting, as is common in such incantations, the ritual acts of the āšipu): an agubbû cultic vessel filled with various plants and oils, liquids, gold, silver, carnelian, lapis lazuli; various types of grains; as well as a scapegoat, a sheep, and potsherds (lines 26–41). The incantation ends with Enki purifying the canal, deciding its fate, and with pleas that evil demons and impurities should keep away from the canal (lines 41–61). The rubric of the incantation notes that it is an incantation for opening the “mouth” of a canalFootnote 10 (ka-inim-ma íd ka ĝál-tak4-a-ke4) (line 62).

This is followed by ritual instructions (lines 61–71) prescribing the preparation of offerings on the riverbank to the same gods mentioned in the incantation, together with Šamaš and Asalluḫi, the recitation of the incantation three times, and the purification of the river through a scapegoat and other acts and materials, which eventually will result in flowing of the canal's waters (line 71: mû išširū).

The ritual of the kalû priest (BM 54952)

The small fragment BM 54952 was copied and edited by Ambos (Reference Ambos2004: 198, 261, no. 22) with slight corrections in reading an incipit by Gabbay (Reference Gabbay2005). The fragment preserves the beginning and the end of the kalû ritual for opening a canal, with a catchline to a different building ritual of the kalû (see Ambos Reference Ambos2004: 186:21'). The incipit of the fragment is now duplicated by the catchline on BM 46548: r.9, a tablet containing part of the kalû's lilissu ritual (George/Taniguchi Reference George and Taniguchi2021, no. 446): e-nu-ma ká íd i-pat-tu-ú.Footnote 11 Since BM 54952 was collated (by U. Gabbay) and a few new suggestions are made, it is edited anew below.

Transliteration

1e-nu-ma ká íd i-pat-t[u-ú ]

2ušum-gin7 ní si ši ⸢èn⸣-š[è ì-gi šá damar.utu(?) ér]

3dilmunki niĝin-na ér.š[èm.ma ana damar.utu(?)]

4egir-šu ⸢kešda?⸣ [ ]

Obv. rest broken

Rev.

-

1′(vacat) ⸢na4 ḫu? x⸣ [ ]

-

2′(vacat) pap 7 na4.m[eš? ]

-

3′(vacat) ana igi íd ⸢bi?⸣ [(x)] x x [ ]

-

4′(vacat) ur5.gin7 šid-nu ⸢ù ?⸣ [ ]

-

5′e-nu-ma uš8 é dingir [šub-ú]

End

Translation

-

1When one opens the gate of a canal [ ]

-

2[The Balaĝ-prayer] “Like a dragon full of awe, how long [will you remain] silent” [of Marduk](?),

-

3(with) the Erš[ema] “Honored one, circle!” [to Marduk](?)

-

4Following it, an offering arrangement(?) [ ]

Obv. rest broken

Rev.

-

1’…-stone(?) [ ]

-

2’In sum: 7 ston[es(?) ]

-

3’In front of that(?) canal [ ]

-

4’You recite thus … [ ]

-

5’When the foundations of the House of God [are laid].

Notes

-

2. For the restorations, see Gabbay Reference Gabbay2005, and Gabbay Reference Gabbay2015: 124–125, no. 24.

-

4.Perhaps restore: egir-šu ⸢kešda?⸣ [tara-kás(?) ], cf. Ambos Reference Ambos2004, 186:25': egir-šú 3 kešda a-na dingir é d+innin é dlamma é tara-kás ab-ru mú-aḫ, “Following it, you arrange three offering arrangements for the God-of-the-House, the Goddess-of-the-House, (and) the Genie-of-the-House. You light up a brush pile.” Another possibility is to read egir-šu ⸢sìr?⸣, “after it, you sing” (see Ambos Reference Ambos2004: 198).

-

r.1’.Ambos (Reference Ambos2004: 198) reads at the beginning of the line ⸢na4 mušen⸣ x, “Vogel-Stein,” but such a stone is unknown. Possibly this line refers to the name of a stone that begins with the sign ḫu or a composite of this sign, for example, na4ḫu-luḫ-ḫu, na4u 5-ri-zu, or na4ḫu-la-lu (see Schuster-Brandis Reference Schuster-Brandis2008: 398, 451, 417 respectively), but since the line is broken, it is not clear that this is indeed the sign on the tablet.

-

r.3′.Ambos (Reference Ambos2004: 198) reads ana igi a-pi x x, but it is quite certain that this is actually the sign íd. Perhaps restore [(x) šu]b?-⸢di ?⸣ [ ] at the end of the line, although this, especially the sign šub, is uncertain. For šub-di in a comparable context, see the Nineveh and Babylonian ritual tablets of the Mīs pî ritual (see below § 4). Another option would be to restore ana igi íd ⸢i !?-ta ?-di ?⸣ (or that ⸢ta⸣- begins a second person form).

4. Common features in the different sources for the ritual for opening a canal

There are several common features in the different sources for the ritual for opening a canal listed above, such as the mythological or ceremonial digging with a spade and basket made of precious metals (in the incantation SpTU 2, 5 and in the Kaštiliaš inscription); the dedication of turtle figurines (in K.2727+ and in the inscription of Sennacherib); the use of stones and other materials (in K.2727+, the Sennacherib inscription, the ritual BM 54952, and the incantation SpTU 2, 5), and some of the gods associated with the ritual (Ea in K.2727+, the Sennacherib inscription, and the incantation SpTU 2, 5; other irrigation gods in the Sennacherib inscription and the incantation SpTU 2, 5; netherworld or ancestral gods in K.2727+ and SpTU 2, 5). These features can be summarized as follows:

Table 1: Overview of specific and common features in the sources for the ritual opening of a canal

The gods participating in the ritual for opening a canal

The gods mentioned in K.2727+ can be divided into two groups, the first consisting of Ea,Footnote 12 and the second consisting of Mummu, Qingu and Ešret-nabnīssu. The ritual text itself shifts from one group to the other a few times, indicating not only the common presence of netherworld and ancestral gods in rituals, but also the specific association with water bodies. This is clearly indicated in the text by the different ritual actions and even in different ritual spaces or zones.

These groupings are not different from other ritual initiations, where there is a distinction between ancestral, primordial, netherworld gods, and “living” gods connected to the world, social order, and abundance. Thus, e.g., in the lilissu ritual, and especially in its commentary, there is a distinction between Enmešara and Enlil (Gabbay Reference Gabbay2018), and in building rituals, there is a distinction between various gods related to the building of the house, as well as prosperity and purification (Ambos Reference Ambos2004: 26–28), and netherworld gods such as Enmešara (Ambos Reference Ambos2004: 70).

In the incantation SpTU 2, 5 (lines 14–19), only one group of gods is mentioned, but this group, although not explicitly distinguished, can be seen, too, as consisting of two sub-groups. The first includes gods related to the qualities of the canal as providing abundance (Ea, in charge of the sweet subterranean waters; Adad, in charge of rain; Enbilulu and Enkimdu in charge of irrigation),Footnote 13 and the second includes the geographical (and cosmological) aspects of the canal that can be related to the netherworld: Ninazu, a netherworld god here related to the river, given the epithet lugal íd-da // bēl nāri, perhaps as an extension of the netherworld river (see Horowitz Reference Horowitz1998: 355–359); and Šakkan, a god associated with life in the steppe and pasture, but also with the netherworld (Wiggermann Reference Wiggermann2021: 602–605).Footnote 14

The primordial netherworld gods Mummu, Qingu, and Ešret-nabnīssu mentioned in K.2727+ are closely connected to the primordial gods known from Enūma eliš, vanquished by Ea and Marduk in their mythological battles. Mummu, Apsû's vizier, is captured by Ea in Enūma eliš (I:69–72; Lambert Reference Lambert2013: 54–55), and thereafter is kept with a nose-rope in the hands of Ea in his dwelling in the Apsû.

Qingu and Ešret-nabnīssu, “His ten creation(s),” correspond to the eleven creatures created by Tiāmat, among which she elevated Qingu (i.e., implying that beside Qingu there were ten creatures, as in the ritual, where they are grouped collectively with a divine determinative) in Enūma eliš (I:146–148 // II:32–34 // III:36–38, 94–96; Lambert Reference Lambert2013: 58–59, 64–65, 76–81).Footnote 15 The fate of Qingu and the creatures is described after their battle, led by Tiāmat, with Marduk, in Enūma eliš (IV:115–122; Lambert Reference Lambert2013: 92–93), where they, like Mummu before them, are said to be captured and bound.Footnote 16 Later, the eleven creatures (implying Qingu and the other ten creatures) are mentioned again as bound at Marduk's feet, and then Marduk creates images of them at the gate of the Apsû as a sign to remember the mythological event (Enūma eliš V:73–76; Lambert Reference Lambert2013: 100–102).

The ancestral gods mentioned in the ritual text are the gods which were left over from the mythological battles with the water bodies of Apsû and Tiāmat. As is made explicit in Enūma eliš, the eleven creatures (corresponding to Qingu and Ešret-nabnīssu in the ritual) and the images of these gods were placed in the “Gate of the Apsû” as reminders of the mythological battle, and in the ritual, it is the “Gate of the river,” associated with the Apsû, that is exposed, where these gods are mythologically held by Ea. The flowing of the abundant waters in the rivers when opening the canal is another “triumph” of Ea over these monsters (see also below). Therefore, the offerings in the ritual texts to these gods connect the ritual acts to the mythological acts, accepting the everlasting tension between the “living gods,” especially Ea, and the “bound” ancestral gods, and ensuring that this tension will remain to the advantage of Ea.

The river and the removal of its earth

The ritual K.2727+ emphasizes the earth piles (eperū) coming out of the canal, and ritual actions are performed on this earth (the laying of the stones and turtles).Footnote 17 Also the incantation SpTU 2, 5 emphasizes this earth, beginning with the words “canal, whose earth is removed” (l. 1).Footnote 18 This removal of earth by regular human labor is mythologically connected to the divine sphere. The text emphasizes that the tools used for this labor were made of precious materials, thus pointing to their divine and pure nature. This is emphasized in the same incantation: “Its soils are carried with a spade of silver, with a spade of copper, with a basket of lapis lazuli” (lines 12–13).Footnote 19 After the earth was removed, the gods let the water flow in it: “They (= the gods) had this river carry the waters of life, the everlasting waters” (lines 20–21).Footnote 20

Similarly, Kaštiliaš III describes the excavation work on the Sumundar canal: “By order of Enlil, my lord, I dug the Sumundar waterway with a silver spade. I carried the earth in a silver basket. I established everlasting water for Nippur” (Abraham/Gabbay Reference Abraham and Gabbay2013: 184:10–15).Footnote 21 Only after the earth is removed, can the everlasting water of life flow in the river. That the tools used are actually divine tools can be deduced from their placement in front of Enlil after they were used in the Kaštiliaš inscription (lines 15–17). These tools, through their ritual use, are connected to the mythological canal digging of the gods in primordial times, as described, e.g., in the Atraḫasīs epic (see Abraham/Gabbay Reference Abraham and Gabbay2013: 191).

This divine act is also described in an incantation to the river performed during Namburbi rituals: “You, river, creatress of everything! When the great gods dug you, (var. adds: the Igigi gods removed [your earth piles]), they placed favor (var. abundance) in your banks. Within you, Ea, king of the Apsû, created his dwelling” (Maul Reference Maul1994: 86:7'–11'; Lambert Reference Lambert2013: 397:1–4).Footnote 22

Thus, the gods dug the watercourses, removed its earth, and let abundant water flow, and this enabled Ea to dwell there. In the ritual for opening the canals, the humans continue this task, ensuring the everlasting flow of waters, both for the future, but also connecting it to the past, namely to the mythological times before humans were created. The water that flows after the removal of the earth is ritually defined and consecrated as the water of the Apsû, and this could only be done through the removal of the earth which prevented the connection between the Apsû and the water in the canal. In other words, the water canal is the water of the Apsû. The ritual act thus connects the water on earth flowing in the form of a canal to the groundwater of the Apsû. This also enables Ea to dwell in these waters and continues the everlasting struggle between the waters of life and the earth clogging up the watercourses, or mythologically, the everlasting struggle between Ea (and other gods) with the netherworld gods who wish to take over the same watercourses (see above). The victory of Ea in this struggle is ritually achieved by placing the pure stones and metals on the earth that was dug from the canal. Nevertheless, it is acknowledged that by removing the earth, mythologically connected to the netherworld deities and fierce creatures, some loss is caused to these deities, who although “bound” by Ea, are not killed nor disregarded, but just controlled, and therefore they are compensated for this earth by the gift of the golden disks to them.

Stones used in the ritual for opening a canal

K.2727+ lists twice a group of materials, consisting of metals (ĝiššinig, útuḫ-lam, ĝišgišimmar.tur, gi.šul.ḫi, ĝiš.búr) and stones (na4gug, na4za.gìn, na4nír, na4muš.gír, na4babbar.dili(meš), na4babbar.min5, ia 4-ni-bu) that are used for purification. These materials correspond to materials used in other rituals too, especially Namburbi rituals, but also in others (Maul Reference Maul1994: 41–44; Ambos Reference Ambos2004: 71–73).Footnote 23 While in Namburbi rituals these materials are used in the libation vessel (agubbû), and then they can be used separately for other purifications (Maul Reference Maul1994, 44–45), in K.2727+ the materials are first placed on the heaps of earth dug out of the canal, and only later placed in the libation vessel.Footnote 24 Perhaps, unlike other Namburbi rituals which use pure waters of an already flowing river, the ritual in K.2727+, which deals with the initial purification of the river, first has to take care of the purification of the materials related to the digging of the river itself.

Although the aforementioned stones appear with purification materials in other rituals too, it is noteworthy that both the Bavian inscription of Sennacherib and the kalû ritual BM 54952 specifically emphasize the same list of seven metals and stones. This is probably due to the emphasis on the pure minerals quarried from the earth and mountains in contrast to the earth dug out of the canal. It should be noted that the lists do not fully correspond: In BM 54952 only the summary “seven stones” is preserved. In the Bavian inscription, the first four stones correspond to those in K.2727+ (na4gug, na4za.gìn, na4nír, na4muš.gír), then na4babbar.dilimeš is listed, the plural probably corresponding to both na4babbar.dili and na4babbar.min5 in K.2727+. The Bavian inscription concludes with the general “selected (precious) stones” (abnī nisiqti, see CAD N/II, 271–272), while K.2727+ lists the yānibu-shell.

The use of turtle figurines in the ritual for opening a canal

Turtle figurines are attested not only in K.2727+ and in the Sennacherib inscription, but in other rituals connected to rivers (compare Weszeli Reference Weszeli2009-11: 180). In the Nineveh ritual tablet of the Mīs pî ceremony, after the procession from the craftsmen's house to the river, the āšipu performs these ritual actions on the river bank (Walker/Dick Reference Walker and Dick2001: 43, translation following p. 58):

These lines are restored according to the Babylonian ritual tablet, which are formulated slightly differently (Walker/Dick Reference Walker and Dick2001: 70, translation following p. 78):

According to Walker/Dick (Reference Walker and Dick2001: 58 n. 78), Ea reclaims these tools since he is the one together with the craft-deities, who created the god of the cultic statue. The figurines of the tortoise and turtle are represented, because these animals – as amphibians – act as messengers or mediators between two worlds: the land and the waters, the human world and the Apsû, thus standing in a liminal position (see Abraham/Gabbay Reference Abraham and Gabbay2013: 192 n. 48). Indeed, in iconography, especially of kudurru stones, the turtle represents Ea, king of the Apsû (Seidl Reference Seidl1989: 152–154).Footnote 25

The connection between the turtle and the Apsû is clearly described also in the Old Babylonian composition Ninurta and the Turtle (Alster Reference Alster, Michalowski and Veldhuis2006), where Enki fashioned a turtle (ba-al-gu7) from Abzu's clay and put it at the entrance of the Abzu itself (lines 36–37). Although some parts of this myth remain mostly unclear, it is possible that the subsequent rituals resemble this myth that features the turtle as a guardian of the Abzu.

Moreover, among the several literary and administrative texts,Footnote 26 where the níĝ-bún-na-turtle is attested, the same concept might probably be also found in the Old Babylonian turtle incantation VS 17 12 (Owen Reference Owen1981: 42–43; Peterson Reference Peterson2007: 411, 418; compare Weszeli Reference Weszeli2009-11: 181), which might be an early source for the ritual usage of a turtle figurine (although it cannot be excluded that the incantation refers to an actual turtle):Footnote 27

The incantation continues with an invocation to abjure the diseases probably of the client (lines 11–14). Without embarking on an in-depth discussion of these problematic lines, which would go beyond the scope of the present study, this incantation shows a connection with the liminal aspect of the turtle between sea and land (lines 1–3).