One obstacle to maintaining well-being in late midlife and older adulthood is an increase in the experience of chronic pain (Kress et al., Reference Kress, Ahlbeck, Aldington, Alon, Coaccioli and Coluzzi2014; Schopflocher, Taenzer, & Jovey, Reference Schopflocher, Taenzer and Jovey2011). Mindfulness – that is, paying attention to the present moment in a non-judgemental way (Sauer et al., Reference Sauer, Walach, Schmidt, Hinterberger, Lynch and Büssing2013) – is an important mental process with the potential to modulate pain (Khoo et al., Reference Khoo, Small, Cheng, Hatchard, Glynn and Rice2019; Zeidan & Vago, Reference Zeidan and Vago2016). The experience of pain varies considerably from day to day (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Ashe, DeLongis, Graf, Khan and Hoppmann2016). However, much of our knowledge about associations between mindfulness and pain relies on global retrospective pain measures (Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Hempel, Ewing, Apaydin, Xenakis and Newberry2017). Daily life studies that assess mindfulness and pain close to their real-time occurrence are less affected by recall bias and can be used to examine their dynamic interconnection (Stone & Broderick, Reference Stone and Broderick2007). In two independently recruited samples, this study examined links between daily/momentary present-moment awareness and pain in the everyday lives of adults 33–88 years of age. This broad age range was chosen because features of what is typically thought of as “old age” might emerge much earlier in vulnerable populations, such as adults who live with chronic disease or those from a lower socio-economic background (Noren Hooten, Pacheco, Smith, & Evans, Reference Noren Hooten, Pacheco, Smith and Evans2022; Steptoe & Zaninotto, Reference Steptoe and Zaninotto2020). Given well-established links between socio-economic status (SES) and the prevalence of chronic health conditions involving pain (Fitzcharles, Rampakakis, Ste-Marie, Sampalis, & Shir, Reference Fitzcharles, Rampakakis, Ste-Marie, Sampalis and Shir2014; Poleshuck & Green, Reference Poleshuck and Green2008), SES was further explored as a moderator.

Pain in Midlife and Older Adulthood

Chronic pain is a common phenomenon in older adulthood and in adults living with a variety of illnesses (Mills, Nicolson, & Smith, Reference Mills, Nicolson and Smith2019; Schopflocher et al., Reference Schopflocher, Taenzer and Jovey2011). For example, up to 50 per cent of individuals who have had a stroke experience chronic pain (Harrison & Field, Reference Harrison and Field2015) and approximately 45–50 per cent of adults over age 65 experience arthritic pain (Barbour, Helmick, Boring, & Brady, Reference Barbour, Helmick, Boring and Brady2017; Statistics Canada, 2020). Chronic pain is difficult to manage and can severely impact quality of life (Kress et al., Reference Kress, Ahlbeck, Aldington, Alon, Coaccioli and Coluzzi2014). Pain interferes with sleep and causes fatigue, and in turn, influences emotional dimensions of pain management and coping (Kress et al., Reference Kress, Ahlbeck, Aldington, Alon, Coaccioli and Coluzzi2014; Marshansky et al., Reference Marshansky, Mayer, Rizzo, Baltzan, Denis and Lavigne2018). Furthermore, older adults who experience pain reduce physical activities such as walking and avoid instrumental tasks (e.g., household chores) that are key for maintaining independence, as compared with older adults experiencing less pain (Kress et al., Reference Kress, Ahlbeck, Aldington, Alon, Coaccioli and Coluzzi2014; Stubbs et al., Reference Stubbs, Binnekade, Soundy, Schofield, Huijnen and Eggermont2013). Individuals show sizeable fluctuations in pain experiences and pain catastrophizing in an everyday context (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Ashe, DeLongis, Graf, Khan and Hoppmann2016; Zhaoyang, Martire, & Darnall, Reference Zhaoyang, Martire and Darnall2020; Ziadni, Sturgeon, & Darnall, Reference Ziadni, Sturgeon and Darnall2018). Hence, it is important to capture the time-varying nature of pain and to recognize that its experience may vary depending on changing mental states as individuals move from one situation to another (Stone, Broderick, Shiffman, & Schwartz, Reference Stone, Broderick, Shiffman and Schwartz2004; Turner, Mancl, & Aaron, Reference Turner, Mancl and Aaron2004). Studies using repeated daily life assessments as individuals engage in their daily life routines and environments may be uniquely suited to examining psychological correlates of everyday pain experiences, because participants report their pain and other psychological processes (e.g., thoughts, feelings) in a way that maximizes ecological validity (Hoppmann & Riediger, Reference Hoppmann and Riediger2009). This approach mitigates concerns about memory biases that can occur when relying on retrospective self-reported pain levels (Walentynowicz, Bogaerts, van Diest, Raes, & van den Bergh, Reference Walentynowicz, Bogaerts, van Diest, Raes and van den Bergh2015).

Everyday Present-Moment Awareness and Pain

Mindfulness is a mental state that has been shown to affect various types of chronic pain (Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Hempel, Ewing, Apaydin, Xenakis and Newberry2017; Khoo et al., Reference Khoo, Small, Cheng, Hatchard, Glynn and Rice2019). Kabat-Zinn (Reference Kabat-Zinn1982) defined mindfulness as “the intentional self-regulation of attention from moment to moment” (p. 34). It is a multifaceted construct and the multidimensional model of mindfulness (Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, Reference Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer and Toney2006) suggests the following five key aspects: observing thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations (inner experiences); being able to describe such inner experiences; bringing awareness to the present moment; non-judgment of inner experiences; and non-reactivity to inner experiences. This article focuses on only one of these facets; namely, present-moment awareness. Much of the literature looking at associations between mindfulness and pain has focused on intervention studies and trained mindfulness (Khoo et al., Reference Khoo, Small, Cheng, Hatchard, Glynn and Rice2019; La Cour & Petersen, Reference La Cour and Petersen2015). Importantly, higher trait mindfulness (a person’s average level of mindfulness across situations with or without prior practice) has been associated with a higher pain threshold (Harrison, Zeidan, Kitsaras, Ozcelik, & Salomons, Reference Harrison, Zeidan, Kitsaras, Ozcelik and Salomons2019). The current study builds on this body of research and extends it by focusing on state present-moment awareness (i.e., how present and aware a person is on a particular day or at a particular moment) and on individuals who do not necessarily have prior formal mindfulness practice. Neurologically, the state of mindfulness goes along with increased activity in brain regions related to sensory processing and decreased activation of brain regions involved in evaluative and emotional responses (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Zeidan, Kitsaras, Ozcelik and Salomons2019; Zeidan & Vago, Reference Zeidan and Vago2016). Despite an increased awareness of pain sensations at times of increased present-moment awareness, negative internal dialogues including rumination, catastrophizing, and negative appraisal of the sensation may be reduced (Grecucci, Pappaianni, Siugzdaite, Theuninck, & Job, Reference Grecucci, Pappaianni, Siugzdaite, Theuninck and Job2015; Paul, Stanton, Greeson, Smoski, & Wang, Reference Paul, Stanton, Greeson, Smoski and Wang2013). Furthermore, mindfulness also seems to be associated with greater pain acceptance (Henriksson, Wasara, & Rönnlund, Reference Henriksson, Wasara and Rönnlund2016), an important factor in adjustment to chronic pain. Thus, a person’s ability to reduce negative thoughts by paying attention to the present moment, along with open-minded acceptance of one’s experiences, seems to be conducive to managing chronic pain. Therefore, individuals are expected to report less pain on days and in moments when they have higher present-moment awareness than usual.

Everyday Present-Moment Awareness, Pain, and SES

Despite a growing body of research on associations between mindfulness and chronic pain, previous studies have often focused on samples who are predominantly white and well-educated (Waldron, Hong, Moskowitz, & Burnett-Zeigler, Reference Waldron, Hong, Moskowitz and Burnett-Zeigler2018). There is a distinct lack of research examining everyday mindfulness and pain in middle-aged and older samples that include under-represented groups such as visible minorities and individuals across the entire socio-economic spectrum. This is important because individuals low in SES (with SES defined by educational level, income, or occupation) carry a particularly high chronic disease and pain burden, likely because of elevated chronic stress, physical labor, more limited resources, and adverse life circumstances (Link & Phelan, Reference Link and Phelan1995; Macfarlane, Norrie, Atherton, Power, & Jones, Reference Macfarlane, Norrie, Atherton, Power and Jones2009; Poleshuck & Green, Reference Poleshuck and Green2008). Furthermore, individuals experiencing chronic pain who are confronted with a high level of economic hardship might show greater pain reactivity to financial worries in everyday life (Rios & Zautra, Reference Rios and Zautra2011). Therefore, this study recognises that the dynamics underlying the proposed mindfulness–pain connection may differ by SES, operationally defined by level of education (a widely-used, reliable, and valid indicator of SES; Shavers, Reference Shavers2007).

The Current Study

This study aimed to investigate time-varying associations between present-moment awareness and pain in adults across a range of socio-economic backgrounds using data from two independently collected samples (secondary analysis; Study 1: 14 daily evening surveys from 89 adults 33–88 years of age living with the effects of a stroke; Study 2: three surveys per day for 10 days from 100 adults 50–85 years). It was hypothesized (H1) that individuals would report lower pain on days (Study 1) and in moments (Study 2) when they reported higher present-moment awareness than usual. Furthermore, it was hypothesized (H2) that individuals higher in trait present-moment awareness would report lower overall pain levels. Finally, SES was explored as a moderator of daily life present-moment awareness–pain associations. Analyses account for pertinent variables associated with mindfulness and pain (gender, age, self-rated health, ethnicity, cognitive functioning; Mahlo & Windsor, Reference Mahlo and Windsor2021b; Mills et al., Reference Mills, Nicolson and Smith2019; Whitlock et al., Reference Whitlock, Diaz-Ramirez, Glymour, Boscardin, Covinsky and Smith2017).

Methods

This article presents a secondary analysis of data from published investigations (Lay, Pauly, Graf, Mahmood, & Hoppmann, Reference Lay, Pauly, Graf, Mahmood and Hoppmann2020, Pauly et al., Reference Pauly, Ashe, Murphy, Gerstorf, Linden and Madden2021; see the Online Supplement for details).

Participants and Procedure

Study 1 included 89 community-dwelling adults living with the effects of a stroke (age range, 33–88 years, mean [M] age = 68.65, standard deviation [SD] = 10.45; 74% male; 85% White) who participated in a study on health behaviors in couples post-stroke (the partner data are not used here) and resided in urban and rural areas of Southern British Columbia, Canada (24% lived more than 2 hours’ driving time from a cardiac care hospital). Study 1 inclusion criteria were that participants were able to handle a tablet device and read newspaper-sized print and that they could walk 10 m (with/without a mobility device). Study 2 included 100 community-dwelling adults living in Metro Vancouver, Canada (age range, 50–85 years, M age = 67.03, SD = 8.47; 36% male). The Study 2 sample was ethnically diverse (38% White, 58% East Asian, 4% other ethnicity) and 35 per cent of participants had incomes falling below the poverty threshold (< 20,000 CAD annually; Statistics Canada, 2019). Study 2 inclusion criteria were that participants were able to complete the study in English (57%), Mandarin (28%), or Cantonese (15%), were able to handle a tablet device and read newspaper-sized print, and had no diagnosed neurodegenerative disease. Participants provided written informed consent and the studies received ethics approval at the University of British Columbia (Study 1: Clinical Research Ethics Board, #H16-01189; Study 2: Behavioural Research Ethics Board, #H12-03117). Participants received up to CAD 100 or a tablet as reimbursement.

After an initial baseline session, participants were asked to complete repeated surveys of their daily or momentary thoughts, affect, and situational context for 14 consecutive days (Study 1, daily morning and evening surveys; only data from the evening surveys were used here) or 10 consecutive days (Study 2, three daily surveys in the morning, afternoon, and evening at predetermined times that fit with participants’ schedules). Participant adherence to the procedure was high (Study 1: M = 12.19 daily questionnaires, SD = 2.91, range = 3–15; Study 2: M = 32.0 momentary questionnaires, SD = 10.01, range = 10–71).Footnote 1

Measures

Everyday present-moment awareness

In Study 1, a single item (taken from the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale [MAAS]; Brown & Ryan, Reference Brown and Ryan2003) measured present-moment awareness in the evening questionnaire: “Today, I found myself doing things without paying attention.” This item was rated on a slider scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much) and reverse coded (M = 74.31, SD = 19.55). The person-average present-moment awareness score (aggregated over the daily diary period) was correlated at r = 0.24 (p = 0.027) with a trait measure of acting with awareness, as measured in the baseline session using eight items from the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (Baer et al., Reference Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer and Toney2006). In Study 2, three times daily, participants were asked to think back to their inner experiences right before they were prompted to fill out the questionnaire and to describe their thoughts using a voice memo or the keyboard. Then, they were asked to rate the contents of these thoughts across a set of items, which included two items measuring present-moment awareness: “I was thinking about something that happened in the past,” “I was thinking about something happening in the future”; these were adapted from one item of the MAAS (“I find myself preoccupied with the future or the past”). Both questions were rated on a slider scale ranging from 0 (not at all true) to 100 (completely true). The items were reverse coded and aggregated to create a composite present-moment awareness score (M = 53.05, SD = 8.66).Footnote 2 We note that participants were not asked about whether they had had any formal mindfulness training.

Everyday pain

In Study 1, participants responded to the question “How much pain did you feel today?” on a slider scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much) (M = 28.17, SD = 27.93; evening questionnaire). In Study 2, momentary pain was measured in the three questionnaires administered over the course of the day by asking about the extent to which participants agreed with “I am in pain,” rated on a slider scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much) (M = 20.99, SD = 19.53, range = 0–100).

SES

Participants indicated their highest level of formal education. For the purposes of the current analysis, a binary indicator was created with 0 = “no post-secondary education” (Study 1: 24%; Study 2: 28%) and 1 = “at least some post-secondary education” (Study 1: 76%; Study 2: 72%). Data on educational attainment were missing for four individuals in Study 2 and were replaced with the mean.

Covariates Footnote 3

Age, gender (0 = male, 1 = female), ethnicity (0 = non-White, 1 = white), self-rated health (from 1 = “poor” to 5 = “excellent”), and animal naming score (as a measure of cognitive functioning/verbal fluency; Acevedo et al., Reference Acevedo, Loewenstein, Barker, Harwood, Luis and Bravo2000) were included as covariates in the models. Study 2 also controlled for time of assessment (0 = morning, 1 = afternoon, 2 = evening). In addition, each individual’s present-moment awareness ratings were averaged across the 14 days (Study 1) or 10 days (Study 2) and this variable was included in the analysis to capture trait present-moment awareness.

Statistical Analysis

To account for the nested data structure (measurement days in Study 1 and measurement occasions in Study 2 nested within individuals), multi-level modeling was conducted using the R package lme4 (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015). Models were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood estimation. Models included a random intercept and a random slope for daily/momentary present-moment awareness at the person level. Daily/momentary present-moment awareness was within-person centred and all other variables were centred at the sample mean, except for binary indicators. Time-varying within-person associations between daily/momentary present-moment awareness and pain (H1) and between-person associations between trait present-moment awareness and average pain levels (H2) were estimated first (Models A and C). Then, the cross-level interaction between daily/momentary present-moment awareness and post-secondary education was included to examine the moderating role of SES on present-moment awareness –pain associations (Models B and D).

Results

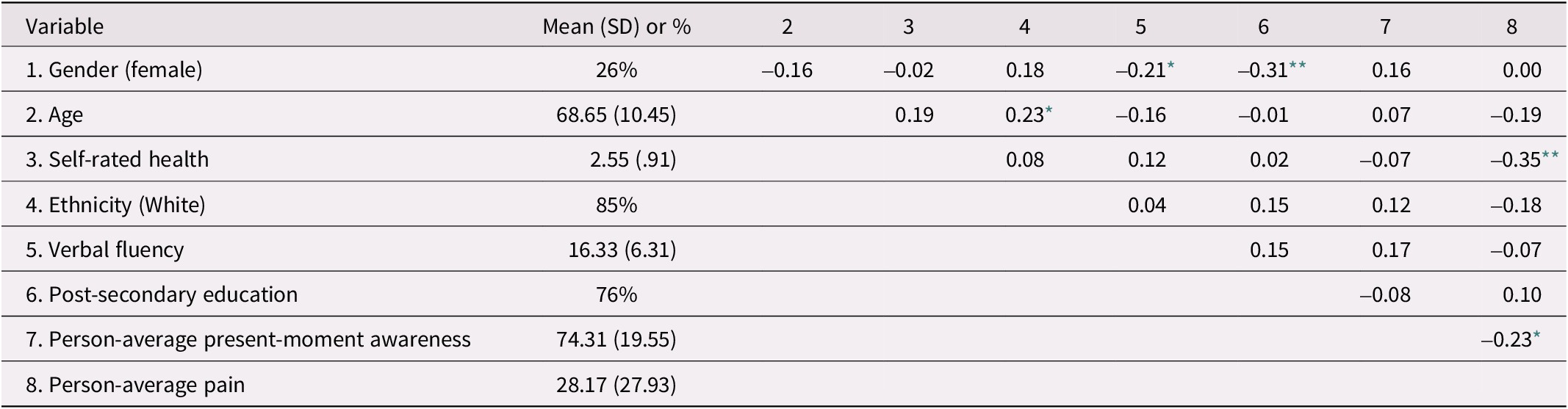

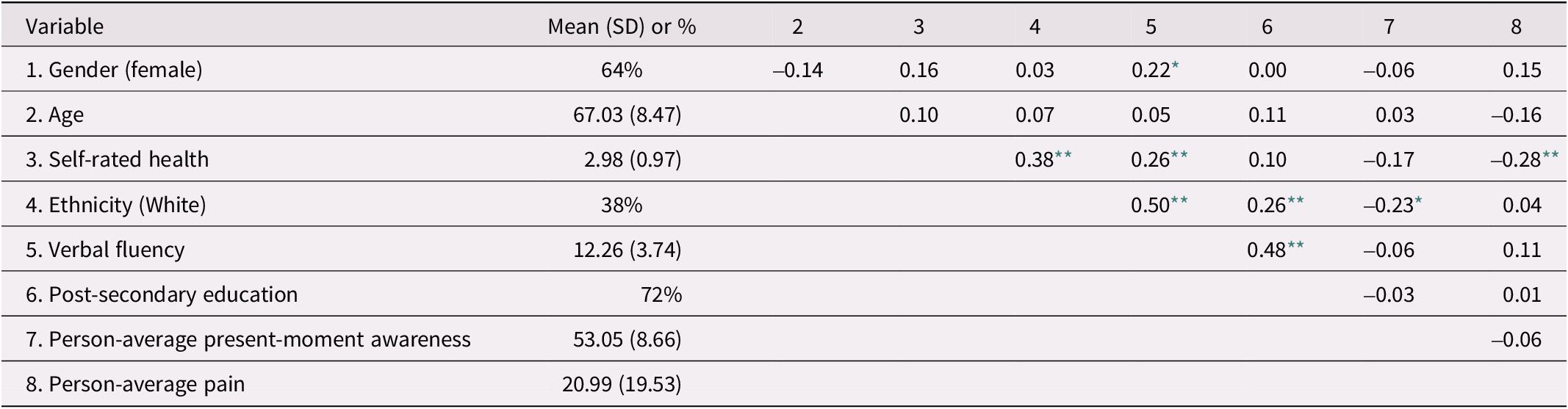

Ms, SDs, and intercorrelations of study variables are reported in Table 1 (Study 1) and Table 2 (Study 2). There was a significant bivariate correlation between person-average present-moment awareness and pain in Study 1 (r = -0.23, p = 0.032), but not in Study 2 (r = -0.06, p = 0.581). In Study 2, participants of White ethnicity reported lower average present-moment awareness (r = -0.23, p = 0.019). In both studies, participants with lower self-rated health reported higher pain levels (Study 1: r = -0.35, p < 0.001; Study 2: r = -0.28, p = 0.005). Verbal fluency was associated with higher education in Study 2 (r = 0.48, p < 0.001) but was not associated with mindfulness or pain.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations (SD), and intercorrelations of central study variables and control variables in Study 1 (n = 89)

Note. Gender was coded 0 = male, 1 = female. Education was coded as 0 = no post-secondary education, 1 = at least some post-secondary education. Present-moment awareness and pain were measured on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much).

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations (SD), and intercorrelations of central study variables and control variables in Study 2 (n = 100)

Note. Gender was coded 0 = male, 1 = female. Education was coded as 0 = no post-secondary education, 1 = has some post-secondary education. Present-moment awareness and pain were measured on a scale from 0 (not at all true) to 100 (completely true).

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

Everyday Pain in Midlife and Older Adulthood

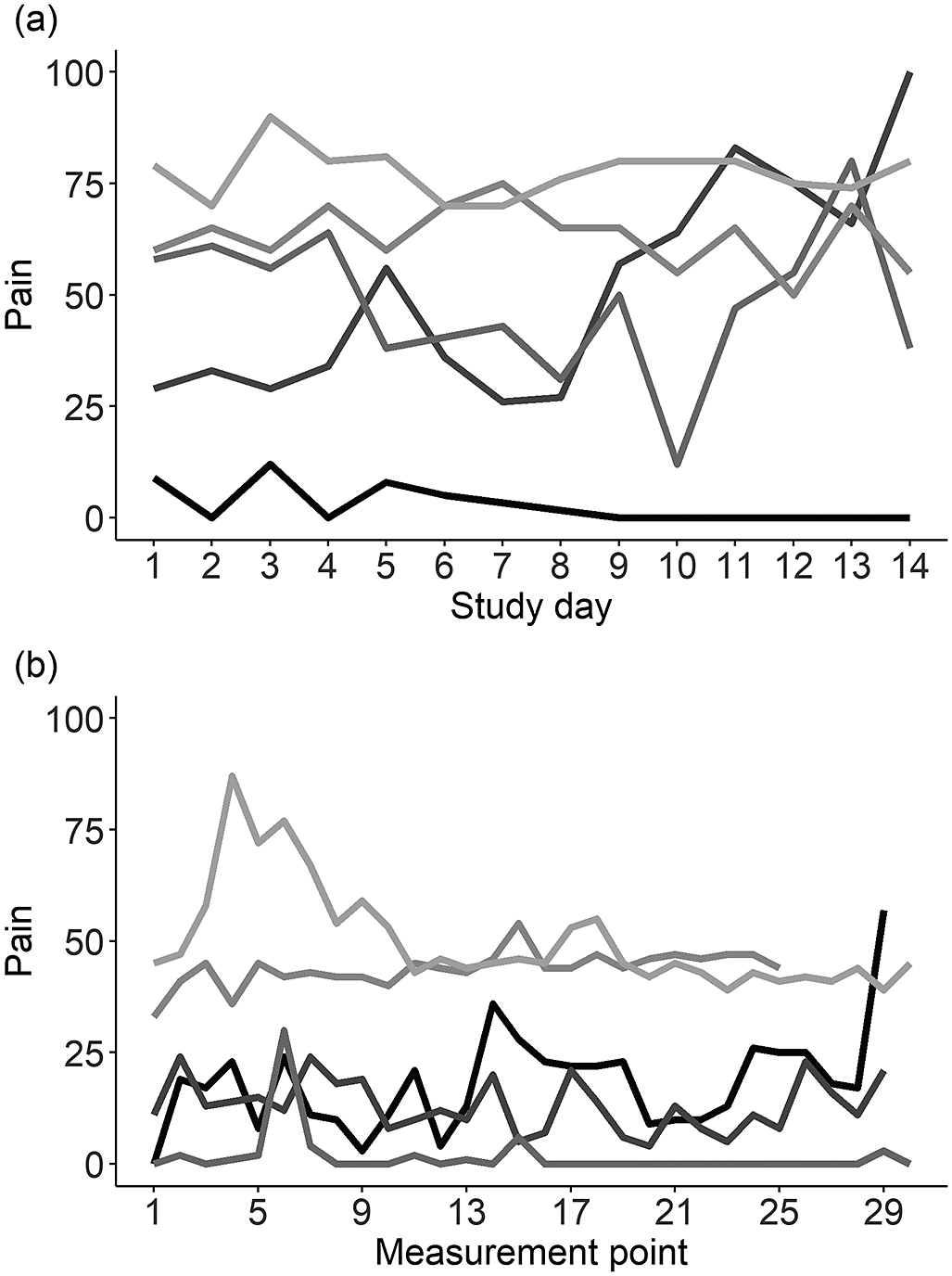

Multi-level models without predictors were estimated to determine how much variance in everyday pain ratings originated from differences among individuals versus differences among assessments within individuals. Pain ratings showed considerable variation from day to day within individuals in Study 1 (35% of variance) and from moment to moment in Study 2 (42% of variance). See Figure 1 for a graphical display of variation in pain ratings for five randomly selected participants in Study 1 and Study 2. Finding such variation justified the additional testing of pain moderators on a daily/momentary level.

Figure 1. Within-person variation of everyday pain ratings. Pain ratings of five randomly selected participants are displayed across 14 days in Study 1 (a) and across 30 measurement occasions in Study 2 (b). Each line represents one participant. It can be inferred that pain ratings varied between persons and within the same person, both across days and within a given day.

Everyday Present-Moment Awareness and Pain

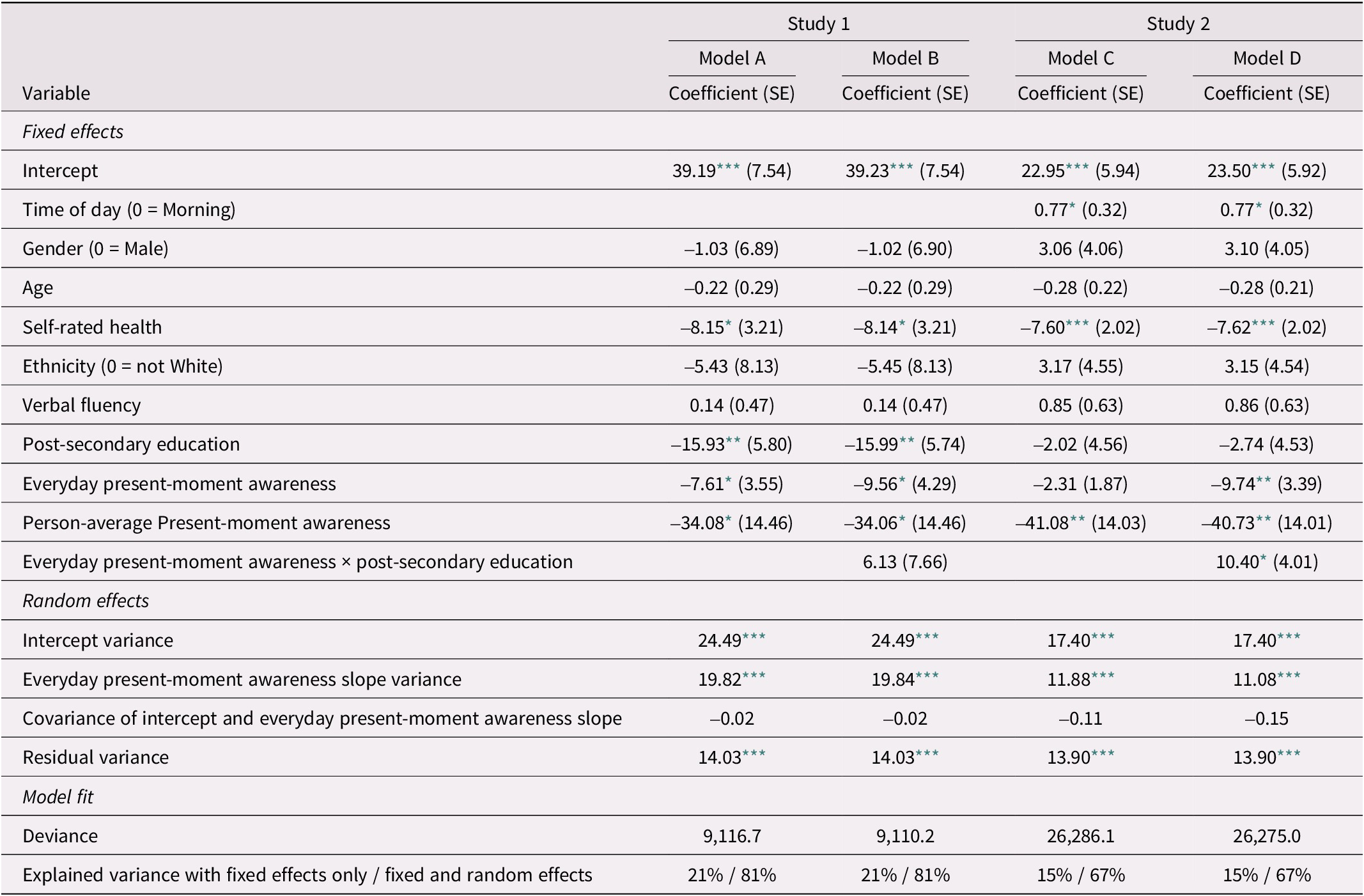

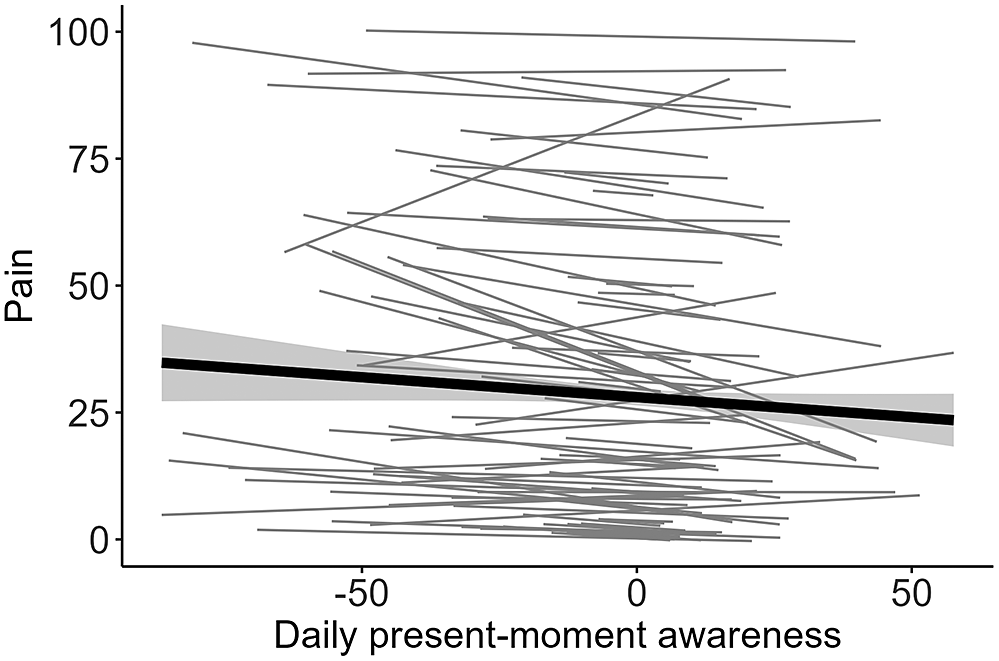

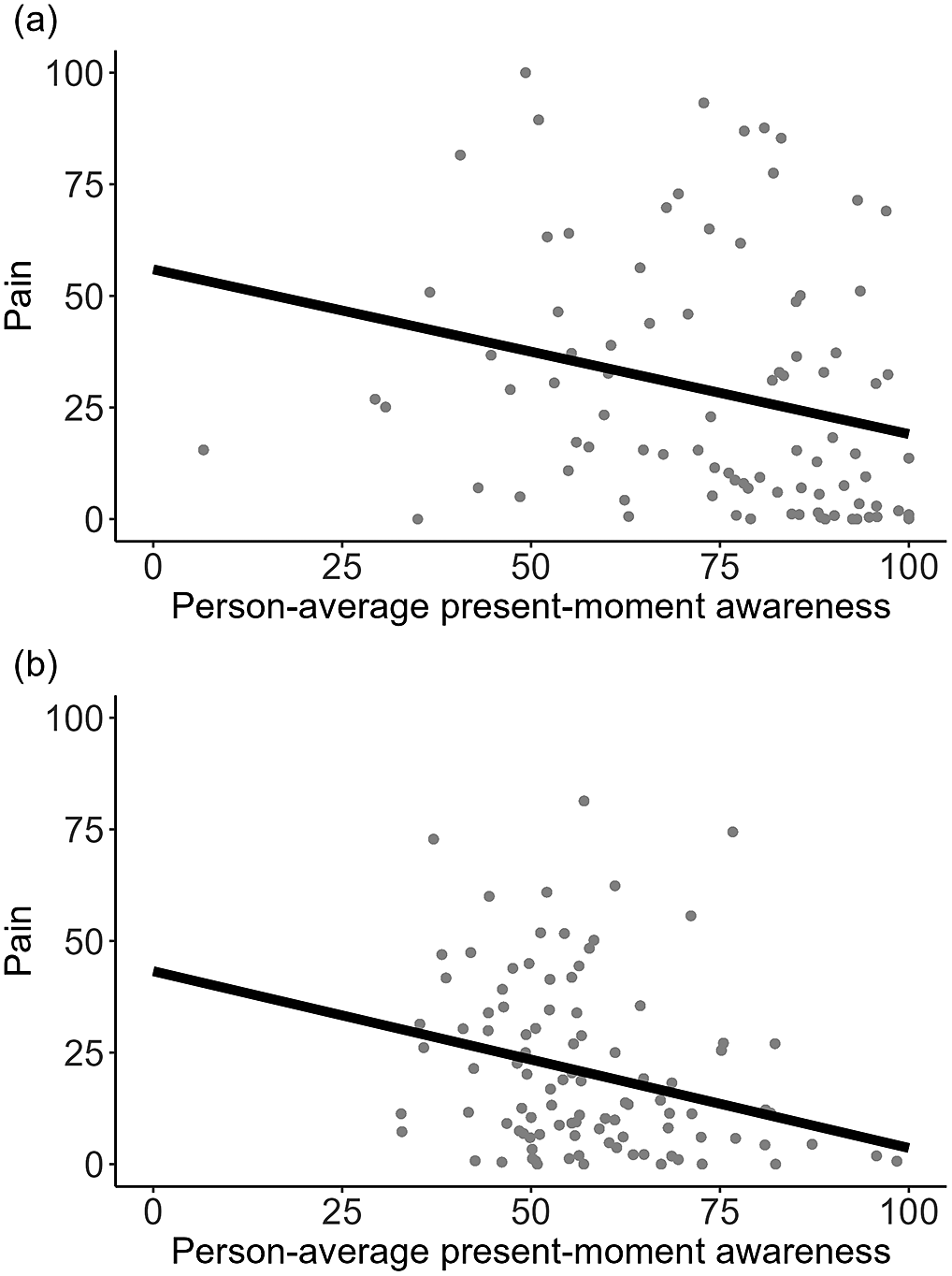

In the first analysis, associations of fluctuations in present-moment awareness over time with daily/momentary experiences of pain were examined (within-person associations; see Models A and C in Table 3). As hypothesized (H1), participants reported less pain on days when they indicated higher present-moment awareness than usual in Study 1 (b = -7.61, SE = 3.55, p = 0.036; see Figure 2). However, there was no significant association between momentary present-moment awareness and pain in Study 2 (b = -2.31, SE = 1.87, p = 0.221). As expected (H2), participants who on average reported higher levels of present-moment awareness throughout the study period, that is, those with greater trait present-moment-awareness, also showed lower average pain levels in both studies (between-person associations; Study 1: b = -34.08, SE = 14.46, p = 0.021; Study 2: b = -41.08, SE = 14.03, p = 0.004, see Figure 3). The percentage of variance explained by fixed effects was 21 per cent (Study 1) and 15 per cent (Study 2).

Table 3. Fixed effects estimates for multi-level models predicting pain in Study 1 (n = 89) and Study 2 (n = 100)

Note. Gender was coded 0 = male, 1 = female. Education was coded as 0 = no post-secondary education, 1 = at least some post-secondary education. Time of day was coded 0 = morning, 1 = afternoon, 2 = evening. Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported. Models A and B are based on 1,083 end-of-day surveys nested within 89 participants and Models C and D are based on 3,195 momentary assessments nested within 100 participants.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

*** p < 0.001.

Figure 2. Model-implied within-person associations between momentary present-moment awareness and pain in Study 1. Participants in Study 1 reported decreased pain on days on which they reported higher present-moment awareness than usual. The gray area depicts the confidence band for the slope. Daily present-moment awareness is within-person centred.

Figure 3. Between-person associations between person-average present-moment awareness and pain in Study 1 and Study 2. Participants who on average indicated greater present-moment awareness reported lower average pain levels, consistently across Study 1 (a) and Study 2 (b).

Everyday Present-Moment Awareness, Pain, and SES

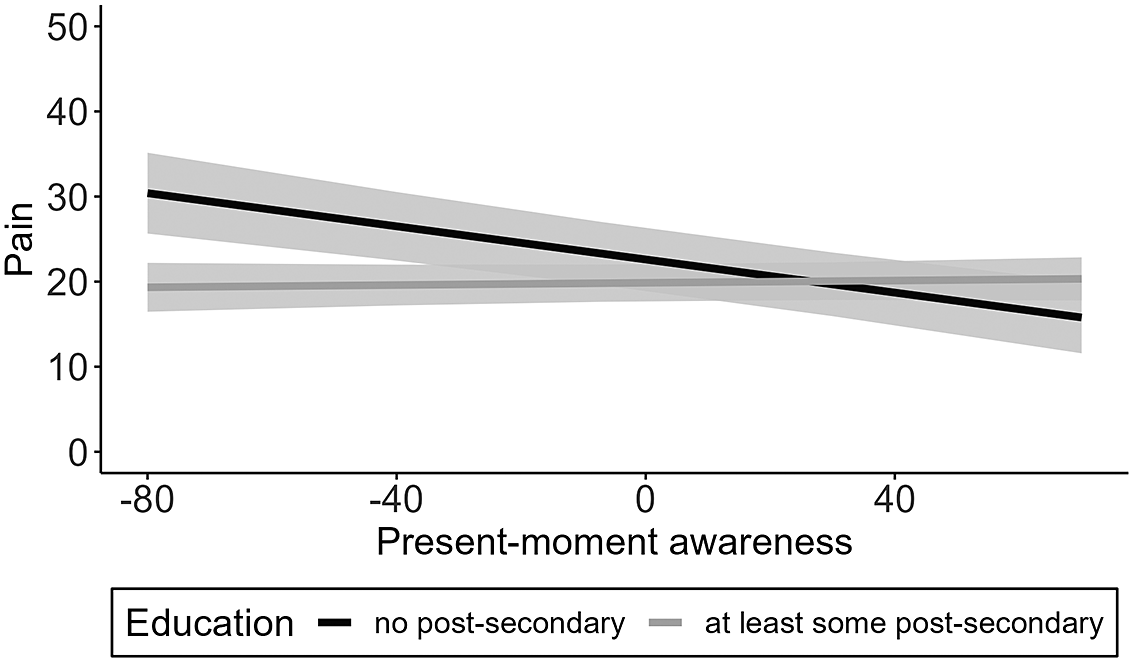

Next, we examined whether education level would moderate associations between daily/momentary present-moment awareness and pain. The cross-level interaction of education on present-moment awareness–pain associations was significant in Study 2 (b = 10.40, SE = 4.01, p = 0.011) but not in Study 1 (b = 6.13, SE = 7.66, p = 0.426; see Models B and D in Table 3). Specifically, present-moment awareness–pain associations were only significant for Study 2 participants without any post-secondary education (b = -9.74, SE = 3.39, p = 0.005), but not among those with at least some post-secondary education (b = 0.66, SE = 2.14, p = 0.546; see Figure 4). There was no main effect of post-secondary education on average reported pain in Study 2 (b = -2.02, SE = 4.56, p = 0.658). However, in Study 1, participants with at least some post-secondary education showed lower average pain levels (b = -15.93, SE = 5.80, p = 0.007). Variance explained by fixed effects was 21 per cent (Study 1) and 15 per cent (Study 2). Model D (including the interaction term) showed better fit to the data than Model C (χ[1] = 6.66, p = 0.010); there was no significant improvement in fit for Model B as compared with Model A (χ[1] = 0.67, p = 0.412).

Figure 4. Depiction of the cross-level interaction between education and momentary present-moment awareness on pain levels in Study 2. Education moderated momentary present-moment awareness–pain associations in Study 2, such that individuals with no post-secondary education reported decreased pain at moments when they indicated higher present-moment awareness than usual. Gray areas depict confidence bands for each simple slope. Momentary present-moment awareness is within-person centred.

Discussion

The current study adds another dimension to cross-sectional research on mindfulness and chronic pain by examining associations between present-moment awareness and pain in the everyday lives of adults aged 33–88 years from a range of SES backgrounds. To do so, parallel analyses were conducted with two independently collected samples, one of which included adults who had experienced a significant health event (stroke) that is often associated with chronic pain (Harrison & Field, Reference Harrison and Field2015). Multi-level models showed that adults who had experienced a stroke (Study 1) reported less pain on days on which they had indicated higher present-moment awareness than usual. In Study 2, higher momentary present-moment awareness was also associated with decreased pain levels, but only among participants without post-secondary education. In both studies, participants with greater trait present-moment awareness showed lower pain levels overall.

Pain in Midlife and Older Adulthood

Average pain levels were about 30 out of 100 in Study 1 (adults who had had a stroke) and about 20 out of 100 in Study 2. This is comparable to pain ratings found with similar samples in previous research (Bergh, Sjöström, Odén, & Steen, Reference Bergh, Sjöström, Odén and Steen2000; Giske, Sandvik, & Røe, Reference Giske, Sandvik and Røe2010) and underscores that pain is a common phenomenon in late midlife and old age (Schofield et al., Reference Schofield, Clarke, Jones, Martin, McNamee and Smith2011). The likelihood that chronic pain interferes with daily activities increases with age (Thomas, Peat, Harris, Wilkie, & Croft, Reference Thomas, Peat, Harris, Wilkie and Croft2004), making it crucial to better understand everyday contexts associated with “good” days and “bad” days. More than one third of the variance in pain ratings was located within persons, meaning that participants showed considerable variation in pain experiences from day to day and from moment to moment. The current study therefore sought to examine present-moment awareness as a mental state that might be linked with everyday pain fluctuations.

Everyday Present-Moment Awareness and Pain

In line with studies investigating levels of mindfulness and pain at only one or two measurement points, greater average present-moment awareness was associated with lower average pain, on a between-person level (e.g., Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Romanow, Rahbari, Small, Smyth and Hatchard2016). The present study extends cross-sectional findings by looking at fluctuations in present-moment awareness and pain in everyday life, investigating the dynamics of the present-moment awareness–pain connection in an ecologically valid manner. In a sample of 89 community-dwelling adults 33–88 years of age post-stroke (Study 1), there was a significant negative association between time-varying present-moment awareness and pain, as rated at the end of the day. In Study 2, which recruited community-dwelling middle-aged to older adults 50–85 years of age, higher present-moment awareness was only associated with lower momentary pain ratings (provided three times per day) among individuals without post-secondary education. There may be multiple explanations for these (in part) discrepant findings. First, the two studies measured different facets of everyday present-moment awareness (Study 1: acting with awareness; Study 2: thoughts focused on present, rather than past or future). Second, Study 2 asked about pain experiences in the moment, whereas in Study 1, the question involved recollecting pain experience over the day. Future research could build on the current findings by collecting data on pain and different state mindfulness facets (Mahlo & Windsor, Reference Mahlo and Windsor2021c) multiple times a day and using an end-of-day diary. Third, present-moment awareness might be particularly important among those faced with health limitations because it improves coping. Another daily diary study (Davis, Zautra, Wolf, Tennen, & Yeung, Reference Davis, Zautra, Wolf, Tennen and Yeung2015) found that mindfulness was the most effective strategy for reducing pain and stress in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, as compared with other strategies, including cognitive behavioral therapy and arthritis education.

Mindfulness training may be particularly useful for chronic pain management. A non-judgmental attitude toward inner experiences such as pain, which can be learned through mindfulness practices, seems to be critical to its effectiveness for chronic pain management (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Qi, Hofmann, Si, Liu and Xu2019). Specifically, acceptance of pain might weaken the link between fearful thinking about pain and pain intensity (Crombez, Viane, Eccleston, Devulder, & Goubert, Reference Crombez, Viane, Eccleston, Devulder and Goubert2013) and can help individuals stay active despite pain (Kanzler et al., Reference Kanzler, Pugh, McGeary, Hale, Mathias and Kilpela2019). Secondary benefits of mindfulness interventions are that they have the potential to increase social support outside of family when administered in a group setting (Whitebird et al., Reference Whitebird, Kreitzer, Crain, Lewis, Hanson and Enstad2013), which can be of further help for chronic pain management (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Colebaugh, Flowers, Meints, Edwards and Schreiber2022). Although some of the intervention studies previously mentioned involved younger samples, there is evidence of the feasibility and acceptability of mindfulness interventions in older adults (Mahlo & Windsor, Reference Mahlo and Windsor2021a; Morone, Greco, & Weiner, Reference Morone, Greco and Weiner2008). Mahlo and Windsor (Reference Mahlo and Windsor2021b) reported that mindfulness facets (e.g., non-judgment and present focus) exhibit both between-person and within-person associations with key variables of well-being and affect; several of these associations were stronger at older ages. Future intervention studies that look at how mindfulness training impacts chronic pain over time in older adults would help clarify whether mindfulness is a promising candidate for pain management for older adults of diverse backgrounds.

Everyday Present-Moment Awareness, Pain, and SES

Present-moment awareness might be a particularly salient correlate of reduced pain experiences for individuals who are exposed to a larger number of life challenges. This could explain why higher everyday present-moment awareness was linked with less pain in Study 1 (individuals who had had a stroke) but present-moment awareness–pain associations were only significant among those participants in Study 2 who had no post-secondary education. Approximately one third of Study 2 participants’ incomes fell below the poverty threshold. Individuals with low SES more frequently report maladaptive coping mechanisms (catastrophizing, rumination; Poleshuck & Green, Reference Poleshuck and Green2008). Therefore, at moments when individuals with no post-secondary education were more aware and present they might have been less likely to use the type of maladaptive coping mechanisms that can exacerbate pain. Future studies should extend the present findings by examining everyday coping strategies and mindfulness-related behaviors such as self-compassion (Hallion, Taylor, Roberts, & Ashe, Reference Hallion, Taylor, Roberts and Ashe2019) in relation to pain–mindfulness links among individuals from all walks of life. This is particularly important considering that there is a lack of research on the utility of mindfulness for alleviating physical health problems among racial/ethnic minorities and individuals of lower socio-economic background, populations that are already medically underserved (Waldron et al., Reference Waldron, Hong, Moskowitz and Burnett-Zeigler2018).

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

The design of the two studies is unique in that people reported their present-moment awareness and pain levels in the context of their daily lives, which maximizes ecological validity (Hoppmann & Riediger, Reference Hoppmann and Riediger2009). The samples include a substantial portion of people of low SES from different ethnic backgrounds to increase generalizability of findings. Specifically, the Study 2 sample included a large number of participants of East Asian heritage. East Asian individuals have been shown to place greater value on inner-focused, reflective, and quiet activities (e.g., meditation), as compared with North American individuals (Tsai, Reference Tsai2007; Tsai, Knutson, & Fung, Reference Tsai, Knutson and Fung2006). Therefore, future research needs to examine cross-cultural differences in links between everyday mindfulness and pain.

Analyses were correlational in nature, and temporal ordering, let alone causality, between the variables cannot be assumed. Another limitation is that this project only measured one facet of state mindfulness (present-moment awareness), using one or two items, depending on the study. Future studies should use a more nuanced and comprehensive measure that captures the multifaceted nature of the mindfulness construct (also including facets of acceptance and non-judgement). In neither of the two studies was information obtained about prior exposure to and experience with mindfulness practices. Considering that exposure to mindfulness-based practices is low in old age and even lower in those with less education (Clarke, Barnes, Black, Stussman, & Nahin, Reference Clarke, Barnes, Black, Stussman and Nahin2018; Olano et al., Reference Olano, Kachan, Tannenbaum, Mehta, Annane and Lee2015), it is likely that a minority of participants in the current studies had prior experience with mindfulness training. Hence, this study’s measure of (untrained) present-moment awareness might not reflect formally trained or practiced mindfulness. However, given literature showing that momentary measures may at times be more closely linked with bodily experiences and health outcomes (Conner & Barrett, Reference Conner and Barrett2012), this article gives added support to the utility of mindfulness for coping with chronic pain. Future studies should also replicate the present findings using a more comprehensive SES measure (e.g., a composite index; Shavers, Reference Shavers2007) and consider lifespan SES by collecting information on past and current socio-economic standing. In Study 2, participants might have interrupted their activities in anticipation of the questionnaires before their scheduled assessment times, which could have influenced the present-moment awareness measure. Finally, the relationship between mindfulness and pain might be non-linear; previous research has shown that low-level pain is often best responded to with distraction, but that once pain is above a critical threshold, an active response is needed that involves behaviors (e.g., taking medication) or psychological processing (e.g., re-interpretation; Johnson, Reference Johnson2005).

Conclusion

The current study investigated associations between (state) present-moment awareness and pain in two samples of adults 33–88 years of age from varied socio-economic backgrounds. Higher daily present-moment awareness was associated with less pain in adults after stroke (Study 1). Education level moderated momentary present-moment awareness–pain associations in Study 2 such that only participants with no post-secondary education reported lower pain ratings at moments when they were more present than usual. In both studies, greater average (trait) present-moment awareness was associated with lower overall pain levels. These findings provide evidence from an ecologically valid design that mindfulness is closely linked with everyday pain experiences.

Acknowledgments

We thank our study participants for making this project possible.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980823000326.

Funding

This work was supported by the Vancouver Foundation (grant number UNR13-0484); and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (grant number G-16-00012717). We gratefully acknowledge support from the Swiss Government Excellence Scholarship and the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant #CR12I1_166348/1) to Theresa Pauly, from the Canada Research Chairs (CRC) Program to Christiane Hoppmann and Maureen Ashe, and from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research to Rachel Murphy (grant #17644).