In fernem Land, unnahbar euren Schritten,

liegt eine Burg, die Montsalvat genannt. …

(In a far-off land, inaccessible to your steps,

there is a castle by the name of Montsalvat. …)

—Richard Wagner, Lohengrin, III.iiiFootnote 1Introduction

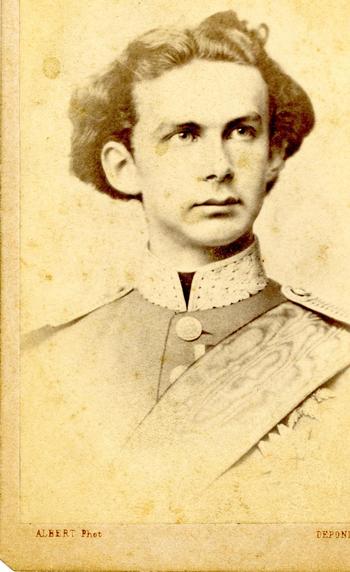

In her 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp,’” Susan Sontag includes Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake (1875–6)Footnote 2 in a list that illustrates “random examples” from “the canon of Camp.”Footnote 3 Though the ballet has become an integral part of the classical repertory for professional companies from Moscow to New York to Sydney as well as the inspiration for numerous figure skaters (most notoriously in Johnny Weir's outré and rhinestone-bedecked interpretation in 2006),Footnote 4 it has, as suggested by Sontag, been creative afflatus for gay underground performers for more than a century. But what are the origins of the swan gone queer? As this article demonstrates, I suggest that one way to trace both the swan's queer genealogy and its continuity lies in the dramatic history and lived performance of the ill-fated Ludwig II (hereafter “Ludwig”) of Bavaria (1845–86)—the Swan King (Fig. 1). Tchaikovsky, after all, had been inspired by the dramatic story of the effete young king (and perhaps titillated by a shared closeted gay desire), who would become a prototype for the ballet's tragic hero, Prince Siegfried.Footnote 5 In fact, dance scholar Peter Stoneley suggests that “Swan Lake confirms the virtual impossibility, in Tchaikovsky's [and Ludwig's] era, of accommodating homosexuality within wider society.”Footnote 6 Ludwig's desire was expressed through a lens of his same-sex fantasies and their inspired artistic interpretations, most notably taking form in the construction of his neo-Romanesque, fairy-tale castle Neue Burg Hohenschwangau (more commonly known as Neuschwanstein or New Swan on the Rock Castle, though it was not renamed until after Ludwig's death). Ludwig's queer positionality also arises from the theatrical way that he performed a highly aesthetic (though hardly effective) approach to monarchy with his swan-bedecked castle and its environs as a sort of metastage set. In this context, the swan may be read as an example of what Donna Haraway calls “a companion species,” or a personal animal symbol (real or mythical) that represents a variety of feelings that are otherwise difficult to express in the hegemonic context of a given time and place (like homosexuality in Roman Catholic Bavaria in the nineteenth century).Footnote 7 Ludwig chose the swan (drawn from family heraldry but primarily envisioned in his own life through storybook-driven fantasy) as a means of alternative expression to that normally available to a man in his position and with his responsibilities, and also as a way to enact his forbidden desires.

Figure 1. Ludwig II as a young king. Carte-de-visite by Albert, Munich; ca. 1864. Source: Courtesy of the Laurence Senelick Collection.

For individuals like Ludwig an animal (whether real or symbolic) may represent the possibility for transformation, if not liberation, through what Haraway calls “a bestiary of agencies,” where the boundaries between nature and culture are blurred.Footnote 8 This notion of blurring presents queerness as a mode of ambivalence—that which “lies hidden between the normative and antinormative and eschews the notions of these binaries as opposite identities.”Footnote 9 Ludwig—who was, by most accounts, tortured by his homosexuality (particularly in the context of his devout Roman Catholicism and attendant guilt)Footnote 10—sought escape in the Alpine wilds, building a fantastical place and space (blurring the boundaries of the real and imagined, the civilized and the wild) where he could attempt to find contentment. He was seeking that “hidden” place where his seemingly incompatible position and desire could coexist. By constructing his dream castle from substantial materials, Ludwig inadvertently created a public monument that endures as an example of Gothic revival architecture and as one of the top tourist destinations in Germany. Ludwig's use of the swan as a totem and talisman to construct places and spaces in an attempt to liberate his queer sexuality performatively calls to mind José Esteban Muñoz's idea of “queer world-making,” where “one is allowed to cast pictures of utopia and to include such pictures of utopia in any map of the social.”Footnote 11 The agency that Ludwig generated through a kind a queer ambivalence made him believe, even if briefly, that utopia could secretly exist between the fairy-tale peaks of his kingdom and the arms of his male lovers. For Ludwig, the swan acts paradoxically as both a public symbol for German tradition and Bavarian regional culture and more introspectively as an underground symbol for queer desire and transformation. Ludwig did indeed map himself onto the Bavarian landscape through his newly constructed and now historically significant palaces (including Neuschwanstein, Linderhof, and Herrenchiemsee), but as examples of the sovereignty and absolute power he desired they were inchoate if not fanciful. They would surpass the symbolic, however, as utopic visions of what Ludwig wanted most—the inherently contradictory desire for both power and freedom—and subsequently as creative inspiration for generations of queer artists to follow.

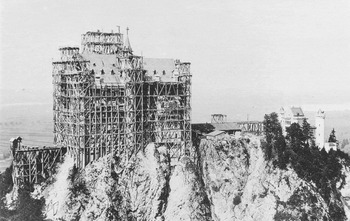

The historical narrative that I have set out to construct herein ebbs and flows, meandering across rather than shooting directly through time. Influenced by J. Jack Halberstam's idea of a “queer temporality,” I reject a singularly linear concept of time in favor of a kind of lateral historiography that brings the past into conversation with the present and vice versa.Footnote 12 Like a wave that falls back on itself, this queer history forms in ecstatic bursts of connection, inversion, and inspiration. I am less interested in the patriarchal history of wars and politics that led to Ludwig's deposition than I am in the arch history that the Bavarian king invented in an attempt to normalize his queer desire. You will also note my tendency to rely heavily on parentheticals. This is a style choice intended to embody commentary as queer aside and not to communicate information that would ordinarily appear in footnotes—a textual version of in-between space. This information often verges on what more economical writers may deem “nonessential,” but I believe that it is through such nonessential details that queer histories began to emerge and thereafter develop into solid structures of alternative genealogy and intersectional scholarship. In the same vein, secondary sources are fundamental to a queerly directed pursuit of Ludwig's story. Primary sources, like Ludwig's love letters, are invaluable as corroborative evidence (like Wagner's Parzival, as scholars, we are all seeking our own version of the holy grail) but because such items are so rare—particularly those that directly confirm same sex desire in a time before the development of gay identity (roughly a decade after Ludwig's death with the criminal libel trial of Oscar Wilde in 1896)—secondary sources so often become the codex to help translate and thereafter synthesize the secret, hidden, and often taboo or shameful subtext(s) within these primary sources. The cultural migration of the swan across the archive as a queer, cultic symbol and as an act of performance is a prime example of such primary and secondary sources in conversation. Although several biographies and glossy photo books have been published on Ludwig (any gift shop in lower Bavaria is packed full of them, translated into dozens of languages), Wagner and the now legendary castle (perhaps made most famous as Walt's Disney's inspiration for Sleeping Beauty's Castle at Disneyland, California and Cinderella's Castle at Disneyworld, Florida),Footnote 13 neither their relationship nor Neuschwanstein (see Fig. 4) has been considered through the lenses of queer theory or theatre/performance studies.

Setting the Stage

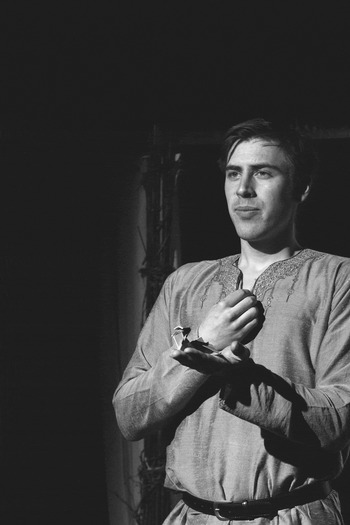

The present article was inspired by the solo show Ludwig and Lohengrin by contemporary Canadian queer performer Kyall Rakoz, which premiered at the Calgary Fringe Festival in 2014. Using only a bedsheet for shadow puppetry and a folded paper swan, Rakoz masterfully played all of the members of Ludwig's inner circle (but never the king) to interpret his tragic life (Fig. 2). In both fabric and storytelling Rakoz layered the saga of Lohengrin, the legendary “swan knight” drawn from Teutonic legend and the title character of Richard Wagner's 1850 opera, because Wagner, German myth, and the swan were Ludwig's greatest obsessions. By employing the white sheet Rakoz created a world of shadows, an in-between, ambivalent space that took shape just beyond the gaze of the audience. The power of this convention, certainly more dreamlike than real, was in its capacity to manifest Ludwig as a kind of spectral king, inhabiting a veiled space where he could avoid public pressures and pursue his queer desires beyond the public eye, free to express himself without scrutiny or expectation. Sadly, this utopic pursuit would never emerge from the shadows during Ludwig's lifetime. It is fascinating to consider that Ludwig may have envisioned a monolithic structure like Neuschwanstein as a place that was queerly invisible, hiding secrets behind its mighty stone walls. This paradox epitomizes the notion of queerness as a space in between the normative and the antinormative; between reality and dreams. If the castle is read as a metaphoric stage set, then it was the events behind the curtain, not intended for the public but witnessed and discussed by Rakoz's characters, that hold the most interest for a queer historiography. Rakoz used this performance as a means to develop original primary conversations by embodying characters who, in their hushed tones, speak about Ludwig's secret life. Working laterally (and perhaps tangentially) from Rakoz's performance, my own investigation into Ludwig as a performer started here.

Figure 2. Kyall Rakoz in Ludwig and Lohengrin; 2014. Photo: Jonathan Brower.

In May of 1861 Ludwig first saw Lohengrin, with its swan-drawn boat, while on a royal visit to Vienna.Footnote 14 Ludwig's family dynasty, the House of Wittelsbach, had used the swan as its symbol for centuries, a choice that took shape most dramatically in a primrose-colored, fourteenth-century summer palace named Hohenschwangau (“place of the high swan”) in the Alps of southern Bavaria. The family laid claim that the spot had been the site of a medieval fortress of swan knights (an esoteric fraternity also known as the Order of Saint Gereon, founded in the twelfth century, that claimed secret connections to the Holy Grail);Footnote 15 this was a place that completely shaped Ludwig's life and his own legacy.Footnote 16 Rebuilt by Ludwig's father, Maximilian II, in the 1830s, the interior walls of the castle were decorated with neo-Gothic murals of Germanic heroes by the artist Moritz von Schwind, including romantic interpretations of the swan knight.Footnote 17 These were completed more than a decade before Wagner composed his Lohengrin, so the young Ludwig was inundated with swan imagery throughout his childhood. Just up the steep mountainside Ludwig would later construct a bigger castle, Schloss Neuschwanstein, on a spot where the foundations of an even older fortress still existed (Fig. 3). (Although the cornerstone was laid in 1869, the castle was not completed at the time of Ludwig's death in 1886.)Footnote 18 There, high above the Bavarian valleys, he could isolate himself and dress as a romanticized version of legendary medieval knights and kings (probably closer in aesthetic to period theatre costumes than to garments that were historically accurate). To this end, the original designs for the building were drafted, unusually, by noted opera set designer Christian Jank, rather than by an architect—although architect Georg von Dollmann was given the titanic task of creating feasible plans from Jank's artistic vision and Ludwig's utter fantasies.Footnote 19

Figure 3. A vintage photograph showing Neuschwanstein under construction around 1860; late nineteenth century. Photographer unknown. Author's collection.

Ludwig rationalized the construction of the castle as a kind of queer utopia, created in an attempt to queer both time and place, where a fantastical queer transformation of himself into Lohengrin could take place. In November of 1865, for example, Ludwig staged a grand water pageant featuring his dear friend, Paul, Prince of Thurn and Taxis, who was drawn across the Alpsee lake dressed as the swan knight, replete with theatrical lighting shipped in from Munich.Footnote 20 This took place on the very lake over which Neuschwanstein would later tower and cast its watery reflection (Fig. 4). By transforming the landscape into a theatrical site with Thurn and Taxis as Lohengrin, this performance perfectly blurred the boundaries between the real and the imagined and turned this location into an ambivalent space. The heightened theatricality of the watery journey combined with the breathtaking landscape must have made it feel like the real Lohengrin had been resurrected, not as a character from the opera, but as a hero from the mythical past who could become a savior for Ludwig's future.

Figure 4. A vintage postcard of Neuschwanstein. Dr. Trenkler Co., Leipzig; ca. 1904. Author's collection.

A Wagnerian Obsession

Long before Tchaikovsky or Ludwig, the swan had been a symbol of transformation and the basis for myths across pagan Europe, from Leda's anthropomorphism in Greece and Rome to the curse of the Children of Lir in Ireland. With the rise of romanticism in the nineteenth century, swan-oriented stories inspired decorative arts and theatrical performances. Napoléon's wife, the Empress Josephine, for example, was particularly fond of the swan as a decorative symbol and covered her French Empire chateau at Malmaison with images of the long-necked bird as a motif. It was in the Teutonic operas of Richard Wagner, however, that the swan was resurrected as a national symbol for the German lands to the east.

The origin of the swan and swan knight as Germanic mascot dates to at least the early thirteenth century, when Wolfram von Eschenbach composed the epic poem Parzival with the character of Loherangrin—a gallant knight who travels in a swan-drawn boat (clearly the creative inspiration for Ludwig's aforementioned water pageant)—at its center.Footnote 21 While Ludwig saw the connection to the medieval world of crusading knights as a romantic link to the past that would promote beauty through art (as well as provide the framework to play out his monarchical role fantastically), farther north around 1848 the Prussian Court resurrected the “Teutonic Order,” a militaristic interpretation based on “values of willpower, loyalty and honesty, and perseverance,” that set up the German knight as a symbol of imperialism and racial purity.Footnote 22 The swan (and other heraldic beasts), symbolic of chivalry and fraternity, would factor into new ideas and aesthetics for nationalism, even before the foundation of the German Empire in 1871. This, of course, proved prophetic for the continued manipulation of German national symbols (including Wagner's operas and Bavarian aesthetics) by the propaganda machine of the Third Reich sixty-two years later.Footnote 23

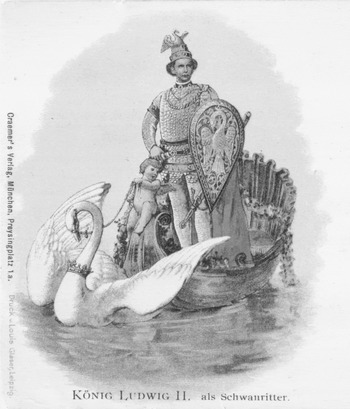

Wagner's Lohengrin (1850), which extends the story of von Eschenbach's swan knight, became the obsession of Ludwig because it provided a histrionic dreamscape with which to diffuse the harsh light of his own reality and responsibilities. Ludwig had reportedly been obsessed with Lohengrin since the age of twelve (when his nursemaid described a performance in detail to the young crown prince), and thereafter he had visions of becoming a swan king—a kind of amplified version of the swan knight for his era (Fig. 5).Footnote 24 This dramatic act was intended to mimic preceding absolute monarchs, such as Louis XIV of France, who had manifested their own sovereignty through the power of symbol.Footnote 25 This pursuit, however, would prove to be purely performative, as Ludwig lost all autocratic power (which was, in any case, never on a par with the ancien régime at the court of Versailles) with the creation of the German Empire in 1870. He was a king with no kingdom but unwilling to give up his crown.

Figure 5. A fantastical image, from a vintage postcard, of Ludwig II dressed as Lohengrin in his swan boat. Craemer's Verlag, Munich; after 1886. Author's collection.

Ludwig's attendance at the opera set in motion his lifelong obsession with Wagner, convincing the king to become a benefactor to the composer-director, whose career had been compromised by stifling debt and accusations of sedition.Footnote 26 Although Wagner's misbehavior continued in the form of a scandalous affair with a married woman, resulting in Ludwig expelling him from Bavaria to Switzerland in 1865 (under political pressure), the men continued a correspondence through rapturous (and excessively hyperbolic) letters. Their correspondence has been partially collected by historian Rictor Norton and which document a kind of protogay relationship, long before either the term or the understanding of alternative same-sex relationships had become a visible part of society.Footnote 27 It is essential to note, however, that Wagner was a notorious womanizer whose relationship with the star-struck young King was likely a matter of financial dependence and genuine fondness rather than any erotic desires. Wagner, it would seem, knew a good thing when he saw one, and as Ernest Newman relates, “The King … was only too happy to visualize himself walking the stage in the role for which his mentor had cast him—that of the savior of German culture.”Footnote 28

Though it is documented that Ludwig took male lovers and would probably be considered gay in a contemporary context, the relationship between the king and Wagner was more accurately homosocial than homosexual, queer in its willingness to discreetly defy conservative conventions of nineteenth-century gender and sexuality as dictated by period conceits of morality and decorum.Footnote 29 A letter, sent from Ludwig to Wagner on 4 August 1865, corroborates the desire of the young king for his musical idol:

My one, my much-loved Friend, –

You express to me your sorrow that, as it seems to you, each one of our last meetings has only brought pain and anxiety to me.—Must I then remind my loved one of Brynhilda's words?—Not only in gladness and enjoyment, but in suffering also Love makes man blest. … When does my friend think of coming to the “Hill-Top,” to the woodland's aromatic breezes?—Should a stay in that particular spot not altogether suit, why, I beg my dear one to choose any of my other mountain-cabins for his residence.—What is mine is his! Perhaps we may meet on the way between the Wood and the World, as my friend expressed it! … To thee I am wholly devoted; for thee, for thee only to live!

Unto death your own, your faithful LudwigFootnote 30

The fine line that separates Ludwig's reality and fantasies becomes clear as he calls upon Wagner's Brünnhilde from Der Ring des Nibelungen (1848) in an attempt to mitigate the complexities of their relationship. While hyperbolized devotion drawn from the romantics was a common model for writing, including letters, in the nineteenth century (with Friedrich Schiller [1759–1805] as one of Ludwig's favorite poets),Footnote 31 Ludwig's declaration of “What is mine is his” feels far more connubial than amicable. It's easy to see why Ludwig's epistolary prose found inspiration in Schiller, whose dramas, often set in the Bavarian wilds, were part of a literary movement titled Sturm und Drang (storm and stress), and moved away from Enlightenment rationalism toward the exaltation of raw emotion. Schiller's particular focus was on tortured and beautiful young men, and the overwhelming affect at the core of the plays often magnified by the wonders of nature; serendipitously Schiller is memorialized in Berlin, his renovated monument fronted by an allegory of Lyric Poetry holding a swan-headed harp.

Between Wood and World

The letter also presents nature as metaphor for escape in Ludwig's desire for a place “between the Wood and the World”Footnote 32 where he can be with Wagner. This works in two ways: first, nature (primarily the Alps of Lower Bavaria) as site to escape from the urban court of Munich and its social prescriptions; and second, a fake, hyperbolized nature amid nature, in the form of the grottoes, follies, and waterfalls created by Ludwig's architects—an act of queering nature as an expression of the king's desire to control and to possess the beautiful. The search for a such a holy place evokes Lohengrin's quest for the grail castle of Montsalvat in Wagner's opera—a divine spot that appears almost to grow from the rocks and that became the key inspiration for Neuschwanstein as a place that rests between the Wood and the World. Ludwig often queered his natural surrounds in an attempt to create a place for utopic escape and reflection. For example, before Neuschwanstein was constructed atop the Ammergau Alps near the Pöllat Gorge, Ludwig would often dine and contemplate life in front of a waterfall illuminated by technicians brought in from the National Theatre in Munich. A contemporary observer and Ludwig's chef, Theodor Hierneis, recollected, “All the beautiful colours were falling down within foaming water, [B]engal magical fire reflecting in a deep violet luminous basin.”Footnote 33 A prime example of a queer ambivalence made manifest, this was a theatrical place that existed somewhere between reality and fantasy: a very real (though powerless) king ruling over an opulent stage set reclaimed from nature. Eventually Ludwig would move from fantasy to a complete break with reality when, much to the architect's chagrin, he ordered that a waterfall be constructed to tumble down the grand stairway of Neuschwanstein—a vision that would never come to fruition.Footnote 34

This theory of the in-between may also be applied to human nature in ways that might be said to realize Muñoz's vision for a queer “utopia” or “fairy-tale worlds” that provide a “mode of fantastical escapism” as well as “a blueprint for alterative modes of being in the world.”Footnote 35 The concept of utopia is as a “no-place,” drawn from Thomas More's sixteenth-century introduction of the neologism as a fictional island but queerly developed by Muñoz through Ernst Bloch's notions of escapism.Footnote 36 The tragedy for Ludwig, however, was that so few of the people around him could access such blueprints, let alone have the queer desire to read them. Though Wagner and Ludwig undoubtedly shared an artistic passion, the former's virile desire for the opposite sex ensured that his relationship with the king was platonic at best. Ludwig could not live happily within the oppressive bounds of normative patriarchy and thus attempted to hide in his fantasies—shaped, in part, by Wagner's artistic vision. When read in a contemporary context, Ludwig's performance of queer ambivalence may be better understood through Haraway's “bestiary,” where “the task is to become coherent enough in an incoherent world to engage in a joint dance of being” resulting in the formation of covert and intimate queer relationships.Footnote 37 Haraway is referring to animal–human relationships, where the inability to communicate (the “incoherent”) becomes the creative source for other modes of communication and intimacy to develop. This line between animal and human becomes particularly poignant when considering that Ludwig could carry on more public and less shameful relationships with his beloved horses than his male lovers. (Ludwig had an entire gallery devoted to portraits of his favorite stallions—an equine version of the Gallery of Beauties [Schönheitengalerie] displayed by his grandfather, Ludwig I, at the south pavilion of Nymphenburg Palace in Munich.)Footnote 38 It was easier for Ludwig to pursue his same-sex desires when he filtered them through narratives of fantasy (like that of the swan knight), considering that a gay relationship was no more coherent or socially acceptable than bestiality in his particular hegemonic circumstances. Whereas Ludwig wished to fly with the swans, he was utterly trapped in his gilded cage, sharing intimate secrets with his horses. Wilhelm Dieterle's German-language silent film Ludwig der Zweite, König von Bayern (Ludwig II, King of Bavaria, 1930) dramatizes this cross-species relationship when Ludwig is shown in a particularly affectionate but melancholy moment with a white stallion in torchlight, stating, “I love animals. They are the only creatures who don't want anything from me.”Footnote 39

Companion Spirits

Richard Hornig is the perfect example of such a lover in human form—a kind of queer anthropomorphism in symbol, if not in practice. He was the dashing stable groom who was promoted to the position of Crown Equerry in the midst of Ludwig's failed engagement to his own cousin, the Duchess Sophie Charlotte (younger sister to Elisabeth or “Sisi,” the Empress of Austria) in 1867.Footnote 40 A diary entry from the king's journal of November 1867 explicitly spells out his forbidden love for the horseman:

I have not received any letters from [Richard], and I feel so sad. My heart is but popping out from my chest, and twice I have cried. Foolish me, for doing so, for I must know that he is unable. I hold his letters to my face, and kiss the signature he's given me, and hold the letters to my skin, closing my eyes and believing he is with me. I wish to have no other men, though I am tempted, and Gott, have I met beautiful boys in Berlin, but they have not his eyes and their voice[s] do not resemble his. I can see him in his bed, naked and perhaps tearful, his long, yellow hair over his smooth back, and I bite my lips, for I hate that he is so far away from me. So far.Footnote 41

While the details of Ludwig and Hornig's relationship must be reconstructed through a few facts and a lot of imagination, artists continue to use the swan as a symbol of queer desire, because the bird has been read throughout history in a variety of paradoxical ways. In medieval Christian folklore, for example, the swan is a symbol of hypocrisy, with white feathers covering its black skin beneath.Footnote 42 This feels particularly poignant in considering the tension Ludwig suffered between the dogma of his Roman Catholic upbringing and his same-sex desire. In contrast, however, is the swan that appears in dreams—a symbol of transformation.Footnote 43 The embrace of transformation is queer here because it offers a kind of protection from the outside world. Although Ludwig was incapable of metamorphosis, he could theatrically transform his world with the aid of designers and architects, opening hidden spaces where he could perform a queerer and more sexualized version of himself. The swan was a token, understood only by the initiated (like Hornig), that allowed entry into these cultic, in-between places ruled by Ludwig as swan king.

The swan as transformative emblem inspired Manga artist You Higuri, who in 2009 published a graphic interpretation (though admittedly more sensual than sexual) of an imagined relationship between Ludwig and Hornig, titled Ludwig II, using the Yaoi or “boy love” genre of Japanese comics.Footnote 44 In one image Ludwig appears in a grotto with a swan, wings outstretched, about to take flight. The low stalactite-filled roof of the cavern, however, stifles this act of upward escape. The king's scarf is looped around the bird, making it unclear whether he is transforming and taking new shape from the swan or vice versa. Although the image first appears to show the king trapped, the grotto is in fact a fantastical folly that Ludwig had built at Linderhof Palace. Based on the first act of Wagner's Tannhäuser, this was a place where Ludwig could queerly play-act as Lohengrin on a stage set without theatrical players—rendering his fantasy tangible if not real. Ludwig's Harawayan companion is the spirit of gay love rendered symbolic through the figure of the swan itself, which, in its intangible form, makes the forbidden or taboo less real and more palatable as a fantasy. Whereas Ludwig constantly struggled to find his dream companion, he spent a lifetime constructing fantastical places in an attempt to attract him. Openly gay film director Luchino Visconti, in his film Ludwig (1973), interpreted the grotto as a kind of campy underground love den where Ludwig, surrounded by real swans bathed in pastel light (originally designed by the same Munich designers who had illuminated the waterfall at Pöllat Gorge), could woo his infatuation of the moment.Footnote 45

Another of Higuri's illustrations shows Hornig as he is visited in his chambers by Lohengrin-as-specter, a character that Higuri has invented as an embodiment of Ludwig's queer desire and imagination. The two men embrace and fade into an illustration of an intimate dance that demonstrates an attempt to preserve the coherence of this world in the face of great challenges. The opening of the graphic novel shows Ludwig imagining this Lohengrin-as-specter, onstage, in the role of a Valkyrie, recalling Ludwig's letter to Wagner and its reference to “Brynhilda's words.”Footnote 46 This manga provides a fascinating example of ecstasy in a distinctly queer mode: when temporality is completely reorganized from the confines of linear chronology, it expands laterally, opening in-between spaces where queer desire is transformed into pleasure. As a graphic novel, Higuri's work illustrates Ludwig's desire for time to stand still through the static nature of its frames, but it also shows how time can be reorganized when frames skip, jump, or leave intentional gaps (like the climax of Ludwig and Hornig's lovemaking). These gaps or absences reveal to the reader the spaces and places where Ludwig may have fleshed out and satiated his forbidden desires. Ironically, it is in the underground recesses of places like the grotto, literally hidden from the prying eyes of the court and the public, that Ludwig could begin to live more openly and dream of taking flight (if just for a moment, forgetting his clipped wings). Obviously Ludwig lived more than a century before queer theory started to unfurl its tendrils from feminist roots, and his world had a tendency to open inward rather than outward; but the interpretation of Ludwig's history as a fairy tale in itself is a poignant reminder of how queer worlds have always been made and how they might serve to generate newer queer worlds—such as this fetishized Yaoi version. Like Ludwig's silk scarf that unfurls in the grotto image, this is an illustration of temporal inversion that, like a Japanese obi, queerly binds the past and present without the limitation of linearity. Ludwig spent a fortune building fetishistic kiosks and rooms inspired by his fantasies of the East (including a Himalayan fantasia in the conservatory of the Residenz Palace and the Moorish Kiosk and the Moroccan House at Linderhof);Footnote 47 but in Higuri's interpretation the gaze of the non-Western subject has been, at least partially, inverted. Karen Kelsky unpacks the complexity of this inversion, or “deterritorialized” space, suggesting that “Western men's long-standing fetishization of the Japanese/Oriental woman is met and mediated by Japanese women's desires for the white man and the Western lifestyle he represents.”Footnote 48 Ludwig's gay relationships as interpreted in Higuri's Yaoi seem to offer a different model for desire, exchanging the binary of dominance and subordination for equitability and a life free from economic concerns. While this queer model is far from the reality of Ludwig's often volatile and isolated life, it does seem to align with the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, centered on an appreciation for “impermanence … and imperfection.”Footnote 49 The origin of a subcultural Japanese obsession with Ludwig is uncertain, but it may originate with ouijisama fashion (おうじさま), a style roughly translating to “fairy-tale prince,” where rebellious teenagers dress up in ensembles inspired by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European monarchs.Footnote 50 Ouijisama crossed over into the theatre and the story of Ludwig in 2000–1, when the all-female musical-theatre troupe Takarazuka Revue presented their original show, Ludwig II: To the Other Side of Dreams and Solitude (ルートヴィヒ II 世 - 夢と孤独の果てに).Footnote 51 This was clearly one of the major inspirations for Higuri's queerly erotic take on the Ludwig myth, providing an alternative intercultural legacy for the Bavarian king, on par with the permanence of the castles he left behind.

Queer Time

Since he was a small child, Ludwig had always adored games of make believe, which, as his mother, Marie of Prussia, recollected, included a particular affinity for “dressing up as a nun.”Footnote 52 While this game was most likely an instance of childhood fantasy and must also be considered in light of blurred gender lines between prepubescent “unbreeched” boys and girls in nineteenth-century families of means, it also speaks to Ludwig's desire to transform himself into someone else, harking back to the swan as a symbol of that transformation.Footnote 53 Whether he was more attracted by a nun's feminine deportment, by piety, or by some delightful ability to reimagine a stiff habit as a broad-winged bird is impossible to know; but this choice certainly highlights a tension beyond the binaries of masculinity–femininity and hedonism–piety-driven guilt that haunted Ludwig's life before his premature death. This dichotomy can also be related to the swan as a symbol of unfixedness. (Ludwig often sealed his personal correspondences with both “a swan and a cross.”)Footnote 54 In the ancient tradition of alchemy, after all, the swan was an animalistic representation of transformation and fluidity, a complex symbol that has been used to represent feminine power associated with the moon, as well as a symbol of virility, represented by the phallic neck. This trope of a masculine/feminine coalescence was at the center of Matthew Bourne's homoerotic, all-male production of Swan Lake in 1995, which also unapologetically queered time with layers of anachronistic references to both the nineteenth century and the current English monarchy.Footnote 55 For Ludwig, it seems that his sexual longing, even if not a protogay orientation was “intensely marked by autoerotic pleasures and histories,” wherein his sinful desires and heretical behavior were diluted because they were couched in a world that was not fully realized or real.Footnote 56 Muñoz notes that such an investment in “fantasy” activates “a challenge to the limitations of the political and aesthetic imagination.”Footnote 57 Ludwig's relationships with men, including Wagner and Hornig, were no less complex and offer excellent examples of this movement between reality and fantasy, swan and human.

Ludwig's obsession with swans and romantic love seems to have started in his adolescence, when, after becoming enamored with images of Lohengrin at the age of twelve, he purchased for himself a “golden swan-feather pen and a medallion with swan and diamond cross.”Footnote 58 Ludwig's queer, romantic vision of medievalism might also be traced to his childhood spent living in Hohenschwangau Castle, because it was filled with murals of beautiful and muscular Teutonic heroes in highly romanticized battle scenes that capture the sinewy virility of masculine bodies in imagined combat, but glaringly absent of the blood, carnage, or horrors of actual war. When one considers the escapist quality of such surrounds, it doesn't seem a stretch to think that Ludwig might have started to envision himself as a fairy-tale prince, engaging in a sort of queer play of the past within the present. Ludwig's manipulation of the temporal and anachronistic is similar to that of fellow Bavarian Bertolt Brecht's subsequent theory of “historification,” where events of the present are set in the past in order to make strange the situation.Footnote 59 Whereas Brecht might have hoped to move his audiences into an attitude critical of the class system that Ludwig represented, the king's attempt to disrupt the linear projection of time, even if unwittingly, alienated himself from reality while also alienating his subjects, who reacted with contempt to the materialistic excess of his reign and the perceived indecency of his decorum. Adrienne Skye Roberts, inspired by Halberstam, suggests that queer time can be a way of reframing relationships based on “a radical reformulation of kinship.”Footnote 60 To this I would add favoring the kinetic—or the ability to move through and across time and build relationships beyond the biological and across generations—over the genetic, a preference that allowed Ludwig to develop surrogate relationships with other men in his at least partially protected world (until it all came crashing down).

Ludwig's attempt to play a fairy-tale monarch in his real life also happened early on, from manipulating the natural landscape (like the illuminated waterfall at Pöllat Gorge) to interactions with his subjects. Historical novelist Desmond Chapman-Huston refers to a specific event when the young Ludwig, accompanied by Prince Paul von Thurn und Taxis, encountered a young, muscular peasant, probably wearing only lederhosen, chopping wood in the mountains near Hohenschwangau. Prince Paul recollected Ludwig's lustful obsession with the ephebic beauty, leaving Chapman-Huston to reflect, “Peasants and kings were always encountered together in fairy and folk tales—so why not now?”Footnote 61 There is no corroborative evidence to reveal what kind of relationship Ludwig pursued with the youth, if any, but this anecdote perfectly illustrates Ludwig's disdain for any social boundaries that impeded his desires. (Ludwig was also sometimes referred to as “Maerchenkoenig” or “Fairy-tale King.”)Footnote 62 It is common knowledge that cross-class relationships between commoners and the monarchy were not unusual, but it seems that Ludwig's desire, paired with an aimless lack of scruples in making his indiscretions public, set him apart.

Without doubt, Ludwig appeared magisterial in style and comportment, but he must also have embodied an utter lack of understanding or sympathy for a lower-class Bavarian population whose economy was changing rapidly in the shadow of Prussia's dominance. Ludwig desperately wanted the control and respect that he associated with Louis XIV—an aspiration that becomes very clear when you are greeted by a scaled-down but nonetheless imposing equestrian bronze of the French king when entering the vestibule at Linderhof (a castle he almost named “Meicost Ettal” as an anagram of the famous dictate “l’état, c'est moi”)Footnote 63—while completely forgetting that the French king's extravagant tastes has been seen as one of the factors that caused the French Revolution and violent abolition of the monarchy almost seventy-five years after his death. Although Ludwig surrounded himself with baroque portraits of the French court in his other palaces of Linderhof and Herrenchiemsee, the specter of Marie Antoinette's apocryphal “Qu'ils mangent de la brioche” (“Let them eat cake”) apparently never took shape in his clouded conscience as a precaution against luxuriant excess (Fig. 6).Footnote 64 Ludwig's obsession with the opulence of the French court is shown in Dieterle's film when Ludwig is seen throwing an intimate, three-person dinner party at Linderhof for the ghosts of Marie Antoinette and Louis XIV, represented by portraits and empty chairs to which he genuflects in homage.

Figure 6. Vintage trade cards featuring the three castles of Ludwig II: Linderhof, Herrenchiemsee, and Neuschwanstein with Elsa and a swan. Leibig's Co., Antwerp; ca. 1898. Author's collection.

Greek Love and the “New Athens”

As Ludwig's lustful attention focused on new paramours, his tradition of gifting swan-themed objets de vertu to the gentlemen in question became common. In 1864 he sent opera singer Alfred Niemann a pair of “jewelled cuff-links with a swan design” after a rousing performance of Lohengrin.Footnote 65 Aside from Hornig the man to receive the most gifts was Josef Kainz, a Hungarian actor famous for his beauty (Fig. 7). After seeing him onstage in 1880, Ludwig had already arranged to send him a pair of ivory opera glasses during the intermission, and only a few nights later presented him with “a diamond and sapphire ring and a gold chain from which hung a swan.”Footnote 66 While the gifts were intended as talismans with which to usher the men (or perhaps more accurately, bribe them) into Ludwig's fairy-tale world, less romantically they branded them as concubines—more possessions added to the king's ever-growing Kunstkammer of beauty. Whereas his grandfather during 1806–30 had amassed ancient Greek and Roman statues of beautiful bodies to fill Munich's Glyptothek, Ludwig selected living, breathing young men for his own collection.Footnote 67 When visiting Munich and observing its historic commitment to neoclassical architecture (particularly the Königsplatz, which is bordered by buildings in the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders), even today it is easy to see what McIntosh refers to as “Drang nach dem Süden” or “a yearning for the South” at the core of the Bavarian capital's aesthetic and political identity.Footnote 68 The theoretical underpinnings of this so-called southern sensibility stem from an Enlightenment desire to look to the orderliness of the ancient world, while also embracing the warm sensuality of the Mediterranean as a contrast to the cold abstemiousness of the High Gothic north. From an early age Ludwig would have been made aware of this southern yearning from contemporary works such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Italian Journey (written 1786–8 but not published until 1816–17), where, in the context of Italy's abundance of antiquities, the poet notes that “I discover myself in the objects I see.”Footnote 69 Ludwig's castles and collections represent an attempt to create spaces where queer love and companionship could take shape: all the fantasy of a Wagnerian romance juxtaposed with neoclassical beauty and made real.

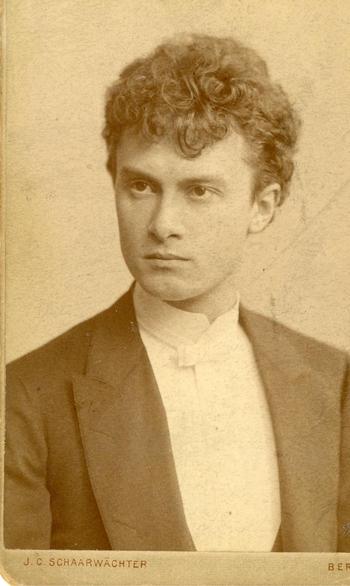

Figure 7. Josef Kainz as a young actor. Carte-de-visite by J. C. Schaarwaechter, Berlin; ca. 1880s. Source: Courtesy of the Laurence Senelick Collection.

The Bavarian preoccupation with looking south resonates beyond architectural styles and aesthetic tastes and brings to mind conceptions of Greek love and Athenian pederasty.Footnote 70 While Ludwig presumably felt lust for the young men he pursued (as corroborated by the emotionally cloying letter to Hornig), as sovereign and patron he also took on a role as a sort of mentor as well as benefactor. The worlds of ancient Greece and Wagnerian medieval fantasy may at first seem disparate, but Ludwig did not discriminate: he built Neuschwanstein as a temple to masculine kinship and fraternal bonding that he fantasized from the legends of courtly knights, though perhaps his vision was closer to an Attic mentorship that was dyadic, homoerotic, and sexual.Footnote 71 Although it had been Ludwig I who transformed Munich into the “New Athens,” it was his grandson who set himself up as a “northern Apollo,” patron of the arts and their progenitors, with a taste for young men akin to the sun god himself.Footnote 72

For a period in the late nineteenth century, Ludwig seemed to take the idiomatic “build castles in the air” as his mission statement. Ludwig's liberal approach to history is elucidated by Muñoz's theory of queer time that allows for “alternate chain[s] of belonging, of knowing the other and being in the world.”Footnote 73 What Muñoz offers here is an alternative definition of queer ambivalence, where “chains” or kinships can provide a space for queer utopia. Sadly all of Ludwig's relationships that attempted to follow this formula of alternatives as a means toward personal fulfillment were fleeting; quite simply, Ludwig felt isolated and lonely. Perhaps because Ludwig was so suppressed by the heteronormative dictates of his time and the restraints of his position, it was only through a fantastical reimagining of the past that he could build any hope for a more fulfilling future.

Ludwig's relationship with Kainz shows how a commitment to the dream realm represented by his palaces (and the narratives he constructed to justify them) grew to overtake his royal duties. Ludwig became lost in his attempt at self-discovery. His attempt at queer escapism was particularly overwhelming toward the end of his life. Soon after seeing Kainz's performance in the Court Theatre (Hofbühne) in Munich, Ludwig called upon him to give private performances, with no one else in attendance. In the early summer of 1880 Ludwig dragged Kainz to Switzerland to reenact scenes from Schiller's Wilhelm Tell (1804) in their actual settings. The king's demands would require the actor to repeat monologues exhaustively for hours, as well as to ascend a snow-capped mountain over the course of two entire days.Footnote 74 Just as the rooms of Neuschwanstein had already been “rehearsed” as opera sets in Munich (particularly the 1867 production of Lohengrin), Ludwig began to blur the epic score and settings of Wagner with his own life.Footnote 75 It was Kainz who represented the start of a final obsessive and reclusive phase for Ludwig. With the palace of Linderhof completed and Neuschwanstein habitable, Ludwig had a physical space to satiate his ineffable desires.

Although Neuschwanstein was built on a scale to accommodate an entire court, Kainz would often give performances to Ludwig alone in the cavernous spaces of the Singer's Hall or the Throne Hall, where Ludwig attended wearing garments from the period of Louis XIV, sometimes with his face obscured by a vizard. Though the mask certainly added an air of drama to the proceedings, the king's vanity was surely the root cause, as he was growing older and gaining weight, particularly in contrast to the beautiful, young Kainz (Fig. 8).Footnote 76 As previously mentioned, it was during this period that Ludwig took on the sobriquet of the “Moon King,” partly in homage to his hero Louis XIV, “le roi soleil,” and partly because the cloak of night provided the shadowy dream world in which he could more discreetly play out his fantasies.Footnote 77

Figure 8. Josef Kainz as the Templar in Nathan the Wise, embodying Ludwig II's fantasy of medieval knighthood and Teutonic masculinity. Photo by Bieber, Berlin and Hamburg; ca. 1892. Source: Courtesy of the Laurence Senelick Collection.

One of Ludwig's favorite sojourns was to take late night, torchlit sleigh rides in magnificent gilt sledges covered with images of swans. For the peasants of the Bavarian countryside, these flamboyant processions must have appeared like visions straight from the Brothers Grimm. Haraway notes that one of the characteristics that defines a companion is the “corporeal join of the material and the semiotic.”Footnote 78 This “corporeal join” expresses perfectly Ludwig's desire for an equally physical, symbolic, and even spiritual manifestation of the swan- as-Lohengrin as paramour and companion, but this would not come to pass. It seems that all of Ludwig's performances, whether in stone or in silk, were an attempt to gild his shame, to hide his loneliness. In the 1986 documentary film Im Ozean der Sehnsucht (In the Ocean of Longing), director Christian Rischert offers the opinion that for Ludwig the swan was employed as a symbol of “purity and loneliness.”Footnote 79 In a mass-produced guidebook available to tourists at all of Ludwig's castles and throughout Bavaria, Dorothea Baumer adds that “the tragedy of Lohengrin was his essential loneliness” (when his anonymity is compromised and he is identified as the swan knight, he must disappear from humanity alone and forever), and that “This was also the fate of the King,” embraced by Ludwig where his reality and fantasies blurred.Footnote 80 Whereas Ludwig could escape the protocol of the Munich court at Neuschwanstein (or any of his castles), his desire for beautiful men was harder to leave behind. To demonstrate this point, Rischert points to a richly decorated jewelry casket in Ludwig's dressing room at Neuschwanstein that features a painting of a medieval nobleman exercising droit du seigneur, or the feudal right of bedding virgin brides of a lesser status on their wedding nights.Footnote 81 While the practice is no more historically corroborated than chastity belts, Rischert suggests that for Ludwig this image symbolized the kind of “evil animal” that Ludwig did not want to embody as monarch.Footnote 82 Thus, in this context, the young king selected the emblematic swan over the rampant (and aggressively virile) lion that had represented his ancestors for hundreds of years. The tapestry decorations of Ludwig's most personal spaces, the living room, dressing room, and bedroom at Neuschwanstein, are like single-species menageries of the mystical bird, with dozens if not hundreds of representations of swans on a blue background—a color of the Wittelsbach dynasty and thus of the kingdom itself.

Perhaps the best example of the confluence of material and semiotic, however, is the Throne Hall in Neuschwanstein. Built in the style of a Byzantine church and dedicated to the fraternity and kinship of the medieval swan knights, it is missing a major component: no throne was ever completed for the king. The empty dais is a poignant symbol of Ludwig's inability to transform his dreams of love and companionship into reality. This empty spot in the cavernous space is a metaphor, a microcosm for a world in which scrutiny, responsibility, and positionality would guarantee that he would always be the Other. Sadly, the swan would never transform into a companion, the longed-for handsome prince that Disney princesses would later achieve without fail in their soulless imitations of his own dream castle.

On 10 June 1886, after being deposed as monarch on the basis of “hereditary insanity,”Footnote 83 Ludwig was forcibly transported from Neuschwanstein to Berg Castle on Lake Stanberg, accompanied by psychiatrist Dr. Bernhard von Gudden. (Ludwig's younger brother and only sibling, Otto of Bavaria, would also be declared insane, most likely a symptom of PTSD after serving in battle. Although he was technically inaugurated as Bavarian monarch after Ludwig's death, his uncle, Luitpold, fulfilled his role as Prince Regent, due to Otto's incapacitation.)Footnote 84 Only three days later the king and von Gudden would be found dead, drowned in the shallow waters of the lake.Footnote 85 There have been a slew of conspiracy theories around the cause of this tragic end, including the idea that Ludwig committed suicide as a mode of escape when his dream world was taken from him. This tragic interpretation was featured in the 2012 German film Ludwig II, written and directed by Marie Noelle and Peter Sehr. In the 2000 musical Ludwig II: Sehnsucht nach dem Paradies (Ludwig II: Longing for Paradise), which was performed in a custom-built theatre in the valley below Neuschwanstein, Ludwig was summoned to the lake and his death by a nymphic voice generated by his fantasies. Though the queer elements of Ludwig's life were highly sanitized in this production, his death was preceded by an orgiastic “bacchanal” in which Wagner's Siegfried and Lohengrin stepped out of fantasy and into each other's embrace in an exaggerated version of Linderhof's Venus Grotto.Footnote 86 While it is impossible to uncover what actually took place, Ludwig's drowning—like that of a swan that could no longer swim and whose mute song is broken only at the moment of death in a “swan song” (presumably a Wagnerian aria)—seems beautifully appropriate.

A Cult of the Queer Swan

Less than two months after Ludwig's death, Neuschwanstein was opened to a curious public. The castles were originally seen as the tacky creations of a Mad King and would not be appreciated for their aesthetic and craftsmanship until the mid-twentieth century. Memorial postcards also appeared almost immediately, partly as a sign of mourning for the king and partly as a business venture to fulfill the late nineteenth-century obsession with collecting ephemera. Even before his death artists took Ludwig as an inspiration for their own work. In the epilogue of his book McIntosh points to several of these early works, including fictional accounts such as Die Königs-Schlösser: Ein Dichtertraum (The Royal Castles: A Poetic Dream [1875]) by Joseph Emruwe and in France, Le Roi vierge (The Virgin King [1884]) by Catulle Mendès.Footnote 87 I am more interested, however, in how Ludwig's legend made him a muse to queer artists producing queer works; works created to fit into that ambivalent space between the Wood and the World. Like that of his contemporary, Oscar Wilde, the mythological version of Ludwig verged on the hagiographic. Occultist and polysexual Aleister Crowley, infamous for his queer relationships and theatrical pageants, included Ludwig and Wagner in his Liber XV: Gnostic Mass (1913). Layering elements of an Eastern Orthodox mass, Masonic ritual, and a period interpretation of pagan ceremonies, Crowley wrote the piece as a magical formula with which to reach a state of “ecstasy” while also serving to shock high-buttoned attendees. The section including Ludwig (his name in Latin form) is as follows.Footnote 88

Lord of Life and Joy … though adored of us upon heaths and in woods, on mountains and in caves, openly in the market place and secretly in the chambers of our houses … we worthily commemorate them worthy that did of old adore thee and manifest they glory unto men, Lao-tze and Siddhartha and Krishna and Tahuti … and these also […] Wolfgang von Goethe, Ludovicus Rex Bavariae, Richard Wagner. …Footnote 89

I am particularly drawn to how Crowley inadvertently picks up on the construct of wood and world (contrasting “wood” and “mountains” with secret “chambers”), setting the stage for an underground ritual that adheres to the same sort of esoteric queerness around which Ludwig built his shattered world. In a parable in part II of Liber XV Crowley presents the white swan as a representation of Ecstasy, on whose back the “little crazy boy of Reason” climbs and rides simply for the purpose of “joy ineffable.”Footnote 90 The swan becomes not only a companion but also the symbolic vehicle that allows the boy to pursue his desire and to seek pleasure for pleasure's sake. In a move that resembles the aesthete's embrace of beauty for beauty's sake (a broader interpretation of nineteenth-century bohemian Théophile Gautier's “l'art pour l'art”),Footnote 91 Crowley inducted Ludwig into his religion of Thelema as a kind of saint for queer possibility, queer potential—as someone who dared to risk everything for who he is (queer) and lives in a more heightened state of irrationality.

A similar elevation of beautiful irrationality as Ludwig's mantra became the core of the creative concept of John Neumeier's Illusions—Like Swan Lake (1976), created exclusively for the Hamburg Ballet exactly ninety years after the king's death. In layering Ludwig with the Siegfried character (in homage to Tchaikovsky's own queer positionality), Neumeier‘s vision has Ludwig losing himself in the fantasy of the ballet, concluding when the death of Odette (the white swan) and Siegfried is mimicked in the King's drowning as an example of mise-en-abyme in performance. Neumeier presents Ludwig's obsession in counterpoint to his oppression, with a performance that takes root in a queer in-between and ambivalent space that blurs the fantasy of ballet with an alternative version of reality based on Ludwig's biography. Neumeier scattered the ballet with a series of symbolic moments, like Ludwig playing with a scale model of Neuschwanstein as if it were a dollhouse that he could control autocratically. This added yet another queer layer to an already queer narrative, boldly interpreting the king's psychological state through choreographic concepts rather than moments based on corroborated historical facts.

In Homos, a text that is foundational to the development of LGBTQ+ studies, Leo Bersani argues: “In a society where oppression is structural, constitutive of sociality itself, only what that society throws off—its mistakes or its pariahs—can serve the future.”Footnote 92 In the contemporary context for which I am researching and writing, Ludwig is symbolic of a queer cultural avant-gardism (both lived and theatrical). Just as his castles and other fantastical constructions have become an economic boon for tourism in Bavaria, more discreetly they stand as testament to a subversive positionality of presence and legacy, still taking shape on the rocky horizon as a symbol of intersectional queer visibility and evolution.

Rising dramatically from a rocky outcrop in the Alpine foothills, Neuschwanstein was created as a place of escape, countering the real world of Munich's court and the limitations it represented. In building the castle Ludwig attempted to create a Muñozian queer space avant la lettre, using the facades and tricks of theatrical designers inspired by Wagner's operas, providing a stage (both symbolic and literal) where he could perform himself as a sovereign drawn from Teutonic legend rather then the figurehead of a principality with fading political power. Although Ludwig has been gone for one hundred and thirty years, his legacy remains in the fantastical castles of Lower Bavaria and the artists moved by them—an entirely new flock of queer swans taking flight.