In this special issue of Modern Italy, four early-career scholars examine how the study of objects and images rooted in Fascist imperialist history enables a sustained interrogation of Italy's colonial imaginary. Their articles explore the diverse possibilities offered by the study of visual and material culture for scholars of imperialism, as it is precisely this realm of visual and material culture that emerges as a site of negotiation in which different individuals and constituencies contended with the regime's ideology.

Visual and Material Legacies of Fascist Colonialism is by no means the first scholarly project to interrogate the relationship between the aesthetic field and the Fascist colonial project. Pioneering studies in different disciplinary fields, as well as contemporary art projects, have addressed the role of architecture, cinema, art and exhibitions in underpinning colonial ideology under the Fascist regime. We have added an extensive (but by no means exhaustive) thematic bibliography on these studies at the end of our introduction.

While building upon the aforementioned scholarship, the aim of this special issue (perhaps one of the most heavily illustrated ever published by Modern Italy) is to highlight how the complementary methodologies of visual and material studies, in tandem, can be used to unpack the colonial imaginary of Fascist Italy. In the next few pages, we probe this approach and apply it to two case studies. We hope that this special issue will act as an invitation to scholars to adopt such productive partnership of visual and material studies for the study of other subjects pertaining to Italian colonialism.

Fascist colonialism and its legacies

Italy was already a colonial power when Benito Mussolini came to power in 1922. In 1882 Assab Bay on the Red Sea became Italy's first overseas territory. Eritrea was militarily occupied three years later and Somalia in the 1890s – the former became Italy's first official colony in 1890. In 1901, in the aftermath of the Boxer Uprising, Italy also gained a share of the European concession in Tianjin, China. But until the ascent of Fascism, Italy's most important colony was Libya, which it invaded in 1911. The following year, Italy also occupied the Dodecanese Islands.

The Fascist regime aspired to strengthen Italy's colonial empire. It crushed anti-colonial opposition in Libya and in the Horn of Africa in the 1920s and, in 1935, invaded Ethiopia. (Italy had already attempted to occupy Ethiopia in the late nineteenth century but had famously suffered a most humiliating defeat at Adwa in 1896.) In 1936, Mussolini officially proclaimed the birth of the Italian Empire. In the Second World War, Italy invaded Albania and briefly occupied British and French colonies in Africa, as well as parts of Yugoslavia, France and Greece. It lost these and all its other colonies at the end of the war. In 1947, with the Paris Peace Treaty, Italy officially relinquished all claims on its former colonies, although Somalia stayed under Italian administration until its independence in 1960.

With the aim of encouraging new scholarship on the visual and material culture of Italian colonialism, and as a point of departure for further studies, this special issue of Modern Italy focuses on the Fascist period. While scholars of colonial history have explored its entire chronological scope, from its beginnings during Liberal Italy to its end after the Second World War (Battaglia Reference Battaglia1958; Rochat Reference Rochat1973; Del Boca Reference Del Boca1976–1984; Labanca Reference Labanca2002; Calchi Novati Reference Calchi Novati2011), the same cannot be said of the study of visual and material heritage. When looking at research interests and scholarly publications on these topics, as well as contemporary art projects, it is palpable that most of the attention has focused on the art and visual culture, museums, collections and exhibitions of Fascist-era colonialism.

Why does the vast majority of the academic debate on visuality and materiality focus on Fascist colonialism (and Ethiopia particularly), leaving pre-Fascist Italian colonialism at the margins? Although there are no ready answers to this question, we can offer some points for thought. Firstly, the Fascist system of colonial propaganda was extremely systematic and pervasive. The sheer quantity of materials produced during the ventennio in terms of colonial collections, art, illustrated journals, printed materials and photographs, films, newsreels and documentaries (many of which are of aesthetic interest in their own right) certainly encourage and stimulate both academic and public attention. Secondly, these materials are complemented by the extensive amount of archival documentation pertaining to colonialism produced by Fascist institutions and ministries – a situation that is not comparable to the fluid and non-centralised construction of colonial consent during Liberal Italy (Labanca Reference Labanca and Del Boca1997, Triulzi Reference Triulzi and Burgio1999, Finaldi Reference Finaldi2009). It is worth noting that before the establishment of the Ministry of Colonies in 1912 (renamed Ministry of Italian Africa in 1937) there was no coordinating institution nor a central museum for colonial propaganda. The Museo Coloniale (Colonial Museum) was inaugurated in 1923 and renamed the Museo dell'Africa Italiana (Museum of Italian Africa) in 1936. It is undeniable that, unlike Liberal Italy, the Fascist regime invested a significant amount of economic and intellectual resources in creating a consistent pro-colonial propaganda through technologies of mass reproduction and mass spectacle aimed at reaching broader swathes of the Italian population. A great portion of this material survives and still absorbs the attention of many scholars and artists – as does the culture of the Fascist regime, more broadly.

Despite our decision to adopt Fascist colonialism as the main focus of this special issue, we have attempted to disrupt its chronological boundaries, selecting papers that reveal the long temporal trajectories of their objects of study. Indeed, the essays in this issue explore the strategic visuality and semantics of a nineteenth-century medium such as photography marshalled at the service of Fascist imperialism (Markus Wurzer), the pseudo-scientific origins of the Fascist intellectual debate on race (Lucia Piccioni), as well as the regime's reshaping of the image of Libya, a pre-Fascist colony (Priscilla Manfren). By looking at the origins of Fascist techniques of colonial mass propaganda, this special issue contextualises the regime's fabrication of consent (Cannistraro Reference Cannistraro1975, De Grazia Reference De Grazia1981, Isnenghi Reference Isnenghi1996, Colarizi Reference Colarizi2000, Duggan Reference Duggan2013) in the longue durée of Italian imperialism. Yet our authors also take into consideration the afterlives of Fascist colonial materials: from the private collections of colonial photographs still in family archives (Wurzer) to the survival and reframing of Fascist colonial photography in the reportages of Epoca in the 1950s and 1960s (Elena Cadamuro). By expanding the temporal horizon of their studies beyond the ventennio, our authors probe the specific ways in which Fascist colonial propaganda strategies represented a continuity or a break in postcolonial memories.

Visual and material culture: a combined methodology

Since the 1990s, the heterogeneous field of visual culture studies has redirected scholarly attention from so-called ‘high’ art to a much wider field of visual production, addressing different images, media, and formats, and crossing categories from the fine arts to popular art, and those outside the artistic realm tout court (Mirzoeff Reference Mirzoeff1998; Evans and Hall Reference Evans and Hall1999). Such a broadening of the idea of the ‘visual’ has allowed its inclusion as part of the toolbox of the increasingly cross-disciplinary field of Italian Studies (Alú, O'Rawe, Pieri Reference Alù, O'Rawe and Pieri2020). When addressing visual culture in such a broader sense, it is crucial to consider images as historical actors and agents that make history, not as transparent evidence of historical events (Burke Reference Burke2001; Jordanova Reference Jordanova2012). ‘Images do not derive from reality’ but rather ‘are a form of its condition’, as Horst Bredekamp writes (Bredekamp Reference Bredekamp and Clegg2018, 283).

Images produced at different stages of the imperial project provide visual histories of Italian colonialism (on the concept of visual histories see Bleichmar and Schwartz Reference Bleichmar, Schwartz, Bleichmar and Schwartz2019). Such visual histories can be embedded in a single image (a painting for instance) or can unfold through multiple images acting together in series or assemblages. The latter case foregrounds how images refer to and reinforce each other, piecing together a complex visual network. The essays in this special issue, indeed, explore photographic albums and private collections, series of illustrated covers of periodicals, racist images and face casts displayed in museums and exhibitions, and photographic reportages reframed in newspapers’ graphic layouts. In brief, our authors do not look at images in isolation but rather at constellations of images. The reproduction, multiplication and circulation of images in several media are central to this special issue. In order to explore the power and agency of images of colonialism (Freedberg Reference Freedberg1989; Gell Reference Gell1998), the dynamics of their dissemination, and their contribution to racist stereotypes and to the standardisation of knowledge as part of colonial discourse, it is essential to see how media work together, and how they overlap and combine in transmedial circuits.

Therefore, our aim is to call attention also to the medium embodying the image, to the material dimension of the colonial past, considering technologies of production and physical qualities as crucial elements contributing not only to the dissemination of images but also to their reproducibility and migration from one object to another; for instance, from a sketch to a print, to a journal cover or to an internal illustration, as well as to other materials and three-dimensional objects.

While visual studies focus on the role of images (broadly defined) in the construction of ideologies and ways of thinking, the study of material culture analyses how the presence of objects and their affective properties are invested with meaning.Footnote 1 Things mediate human relations and are historically specific. Material culture studies unpack the work done by objects on memory: why they were made, who made them, how they were consumed, and how they were signified and resignified over time (Kopytoff Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986, Maquet Reference Maquet, Lubar and Kingery1993, Pearce Reference Pearce and Pearce1994). Things are ‘tools through which people shape their lives’, as Leora Auslander writes, ‘creat[ing] social positions and even (some argue) the self itself’ (Auslander Reference Auslander2005). Thus, artefacts bear traces of the existence of their makers and owners and help us investigate historical changes in consciousness, bodily experience, subjectivity, affect, and emotions – for this special issue, for example, how everyday Italians felt about the Fascist regime, its colonial aspirations, the territories it had invaded, the people who lived there, and the morality of Italy's empire.

For the study of colonialism, material culture is particularly enlightening regarding the relations between the colonised and the colonisers. Mass-produced objects, ephemera and artefacts were used to record, celebrate and question European empires – both at home and in the invaded territories. Material culture studies provide special encouragement to attend to the fundamental ways in which objects are imbricated with ideas and practices in the experience of colonialism (Troelenberg, Schankweiler and Messner Reference E-M, Schankweiler and Messner2021). Such study allows us to address the imaginaries of imperial subjects, examining the role that empire and colonialism played in shaping gender and class roles, the history of the senses and emotions, and subjectivity and consciousness at large.

Although such study has been underway for decades in the case of the British and French empires, in the Italian case these materials are still very much under exploration: we hope that this issue will encourage scholars to address the rich range of objects through which various Italian constituencies implemented a materialised colonial culture, and the dynamics of remembrance and forgetting that its preservation or disappearance reveal.Footnote 2

Yet something gets lost in the study of colonial propaganda when, as scholars, we limit ourselves to either visual or material studies. Rather, when studying the objects produced to buttress imperial domination it might be more productive if these two approaches were in dialogue. In this way, it is possible to address both issues of representation and sensorial presence (Yonan Reference Yonan2011; Cordez Reference Cordez, Cordez, Kaske, Saviello and Thüringen2018; Kaske and Saviello Reference Kaske and Saviello2019). As Angelo del Boca famously wrote, the ‘private museum of Italians’, the collection of weapons, postcards, posters, magazines, albums, and other ephemera that many Italian families still preserve at home – and which might very well include the materials studied by our contributors as well – is both a museum of objects and of images that record, celebrate, and memorialise colonial experience (Del Boca Reference Del Boca and Isnenghi1996). Thus, for this special issue, we encouraged our authors to address both the visual and the material dimension of their case-studies, delving into how their iconography and their physical properties produced meaning, and into how their distribution during the ventennio as much as their preservation today provide crucial information on Italians’ complex negotiation of colonial memory.

Visual and material culture can complement other historical sources of Fascist colonialism, but they also raise new questions and bring overlooked historical actors and practices to the centre. Let us consider two examples of the material and visual culture combined approach that this issue proposes, and its scholarly potential for the study of the entire chronological span of Italian colonialism. In the first case study, adopting such combined methodology allows us to address the transmedial migration of colonial iconographies from images to objects, and how they served to reinforce colonial discourse. In the second case study, visual and material studies complement each other, approaching the same object from different perspectives, and drawing connections between a range of disciplines, from archaeology to critical museum studies.

The Dogali brooch: from mass-produced images to a luxury object

From the nineteenth century onwards, the rise of scientific explorations and colonial enterprises created new needs and opportunities for images to carry weight as purported embodiments of visual facts.Footnote 3 Images allowed viewers to collapse geographical distance, to see (and imagine) landscapes and people living far away, filtered by a familiar European gaze. They also made it possible to travel in time, to experience an event from the past. Yet travelling images cannot produce the affective engagement that objects provoke. In the long history of Italian (and non-Italian) colonialism, images have frequently become objects, and visual culture has morphed into material culture – transforming a serial and reproducible image into a unique item of emotional engagement with historical events.

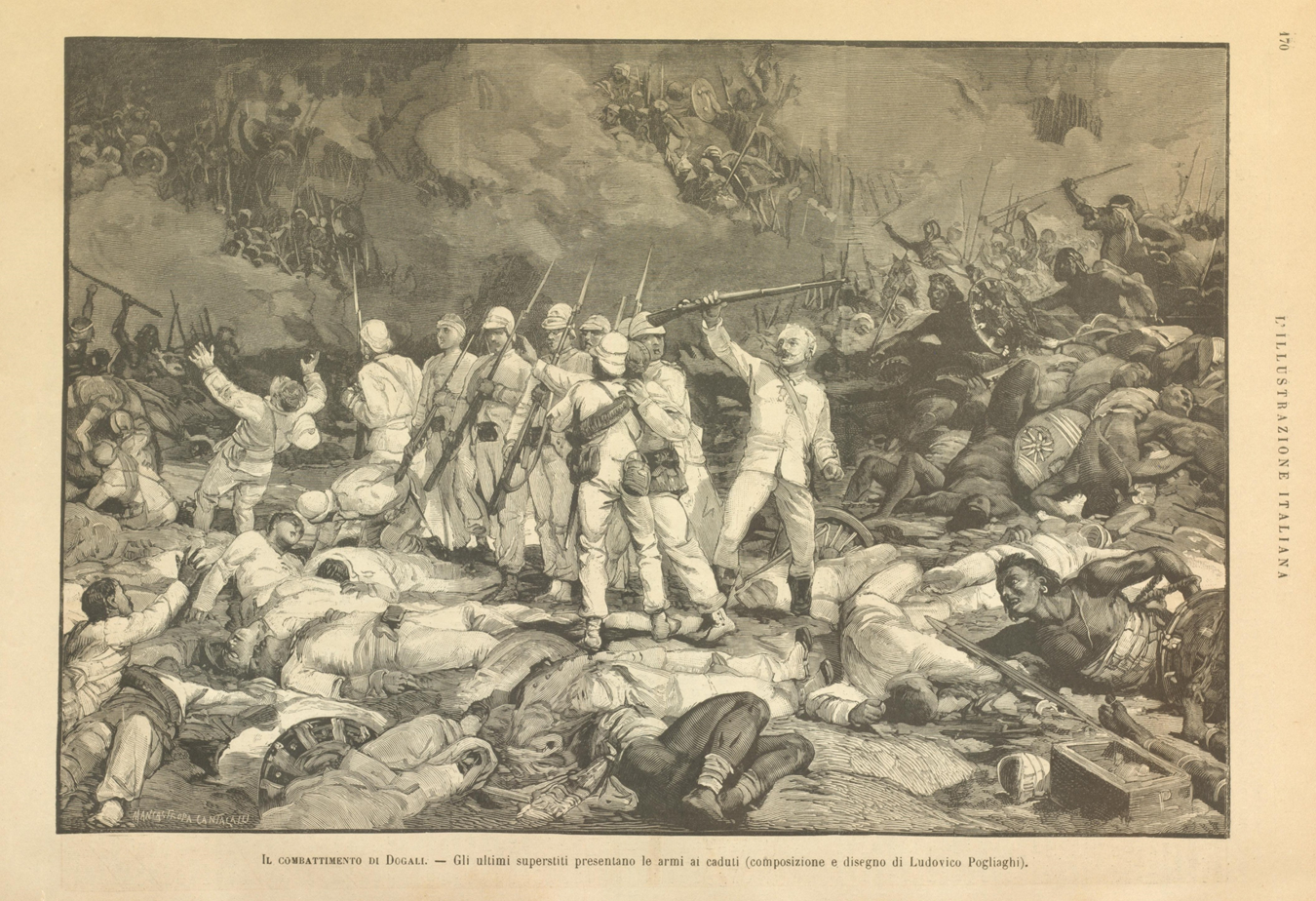

A suggestive example of this process is an extremely popular image of the very first Italian colonial conflict, the battle of Dogali (Eritrea) in 1887, which concluded with Italy's defeat. Approximately a month after the fact, Ludovico Pogliaghi, an illustrator for the bourgeois journal L'Illustrazione Italiana, elaborated an image of the battle ‘dietro schizzi e documenti speditici da Massaua e Moncullo’ (‘from sketches and documents sent from Massawa and Monkullo’), as the journal reported (L'Illustrazione Italiana 1887), as seen in Figure 1. These words, printed together with Pogliaghi's illustration (entitled ‘Dogali Battle – The Last Survivors Present Arms to the Fallen’) corroborated the presumed truthfulness of the visual history of the battle of Dogali provided by the journal.

Figure 1. Il combattimento di Dogali – Gli ultimi superstiti presentano le armi ai caduti (Dogali Battle – The Last Survivors Present Arms to the Fallen) in L'Illustrazione Italiana 1887. XIV, 27, 9 February: 170.

In reality, Pogliaghi's illustration omitted the unfolding of the battle and the Italian defeat by leaving the confused infighting in the smoky background. Rather, he condensed the narrative around Dogali in the scene in the foreground, centring the (possibly apocryphal) heroic gesture of the Italian soldiers presenting arms to their fallen comrades, a sign of respect in European military rhetoric that probably never happened in the heat of the battle. In the strategic interplay between text and image, Pogliaghi's illustration was proposed to the readers of L'Illustrazione Italiana as evidence of Dogali's historical fact, blurring distinctions between eyewitness accounts, official news, and the record of the past.

As part of the dynamics of the late nineteenth-century publishing market, which was increasing investments in journal illustrations in response to the rise of public interest in the chronicles of the first Italian occupation of East Africa, Pogliaghi's version of the battle of Dogali was repeatedly reprinted and published in the popular press, contributing, with its circulation, to building consensus for Italian colonial endeavours (Belmonte Reference Belmonte2021). This process shows the ways in which condensation and simplification, as well as the use of recurring Pathosformeln, contribute to the rhetorical power of the image in question, allowing it to easily enter into and survive in collective memory.

As a storytelling device, Pogliaghi's approach codified a memory of Italy's defeat in Dogali and reframed it as a heroic episode, which travelled from information media to the private emotional sphere. Sometime in the months following Dogali, Pogliaghi's illustration migrated from a two-dimensional sheet of paper to a precious handcrafted jewel as seen in Figures 2 and 3. It was engraved in inverted form by Giorgio Antonio Girardet on the convex surface of blue sapphire, set in a brooch made in the workshop of the Roman goldsmith Castellani (Pirzio-Biroli Stefanelli Reference Pirzio-Biroli Stefanelli2002). The genesis of this precious object (now at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London) remains unclear. We do not know if Castellani realised the brooch as a marketing strategy (hoping to attract a clientele filled with patriotic fervour) or in response to a specific commission from an individual. What we do know is that the subject represented in this jewel is rare in the iconographic repertoire of Girardet, which was mostly devoted to mythological scenes and portraits of ancient and contemporary figures. However, in the precious materiality of the Dogali brooch, what becomes evident is the unexpected survival and reemergence of images in objects, and the unpredictable agency of the multiple actors involved in the dissemination of colonial visual culture.

Figure 2. Workshop of Augusto Castellani: pendant brooch memorialising the battle of Dogali, 1887–8, enamelled gold with pearls, diamond, ruby and a sapphire intaglio, 8.9 x 5 x 1.8 cm, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Figure 3. Giorgio Antonio Girardet, Battle of Dogali, 1887–8, sapphire intaglio set on a Castellani brooch © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The MUDEC manillas: visual narratives of colonial objects

The Museo delle Culture or MUDEC in Milan is a relatively young institution. Since the late 1990s, it was clear to administrators and museum professionals that a new space was needed to display the rich non-European collections owned by the city and exhibited in the Castello Sforzesco. Yet the current museum opened only in 2015, as part of the World Expo and as a self-celebration of Milan as Italy's foremost multicultural city. Designing a new ethnographic museum in the 2000s would prove to be no easy feat, as the controversies provoked by the opening of the Musée du quai Branly in Paris (2006) and the Humboldt Forum in Berlin (2020) demonstrate. Decades of criticism of such a form of display and collecting did not go unheeded by MUDEC curators Carolina Orsini and Anna Antonini. To limit such critiques, Orsini and Antonini eschewed the idea of the ‘non-Western’ as the permanent exhibition's organising principle (with its evident undertones of primitivism and exoticisation) and rather focused on the intercultural exchanges between Italy and non-European communities, both in Milan and abroad.

Another relatively novel approach adopted by MUDEC curators was to not conceal the museum's constructed and historical nature, but rather to address head-on the cultural, social, economic, and political processes through which non-European objects ended up in Milan. From 2015 to 2020, MUDEC's permanent collection was structured around the theme ‘Objects of Encounter’.Footnote 4 After rooms devoted to Milanese Wunderkammern, and to objects collected by Italian religious missionaries, travellers, and political exiles in the Americas, room 3 was dedicated to ‘The Colonial Period: Looting and Despoliation in Africa’. This room addressed the intertwinement between colonialism and capitalism —a distinctive feature of Milan's relationship to the African continent.

This was not, of course, the first time that African art had been on display in Milan. Although it was almost completely destroyed following the August 1943 bombardment of the city, a significant collection of African art was on view for almost ten years in the Castello Sforzesco. This African collection was assembled by Giuseppe Vigoni, Milan's city mayor and a senator of the Italian Kingdom. In 1879 Vigoni became president of the Italian Society for the Commercial Exploration of Africa – an association devoted to identifying those resources that would justify Italian expansion in the African continent. Vigoni's collection was donated to Milan in 1935, on the eve of Italy's invasion of Ethiopia, and it was publicly displayed until the end of the Fascist regime. Only a few objects survived the 1943 bombardment, and one vitrine in ‘Objects of Encounter’ room 3 recreated the way in which much of the Vigoni collection was displayed: as colonial trophies, with no scientific criterion or regard for the different makers and users of these objects.

The most memorable display in this room (and in ‘Objects of Encounter’ as a whole, we would argue), however, was a display case with hundreds of manillas, which were not part of the Vigoni collection but had important overlaps with the provenance of other African objects in Milan's city museums. Manillas are bronze, copper, or brass bands from West Africa. Some are open and horseshoe-shaped with terminations on each side; others are closed hoops. Of varying sizes and weights, some manillas are embellished with geometric motifs while others are plain and austere. They could be worn around the neck or the legs, but most of them were armlets (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Manillas, bracelet money – western and central Africa, nineteenth/twentieth-century. Different engraved metal alloys. Enrico Pezzoli Metallindustria Coll. © MUDEC, Museo delle Culture, Milan.

Manillas shifted meaning and usage over time. From means of personal adornment, indications of fashion, displays of wealth, and symbols of courtship or marriage, they became a form of currency, first used in African societies as dowries and in funeral practices, and then traded by slavetraders in exchange for human beings. During the eighteenth century, hubs for the commerce of enslaved people, such as Bristol and Birmingham, began producing manillas too as currency, but by the early twentieth century they fell into disuse (Edwards Reference Edwards2013). From symbolic objects charged with cultural meaning to currency in the international slave trade, manillas reverted to their pure materiality and after the Second World War were often used as ballast for ships or sold as scrap metal and melted.

The manilla collection on view at MUDEC was saved from destruction by engineer Enrico Pezzoli, who worked as a chemist for the Milanese foundry Metallindustria. The manillas had arrived at the company in the 1960s to be fused and their metal reused. Pezzoli – an amateur numismatist – convinced the owners of Metallindustria to sell them for a symbolic sum to Milan so that they could be preserved together with other non-European objects in the city collections (Orsini and Antonini Reference Orsini and Antonini2015). Although the MUDEC's manillas are not directly correlated with colonialism under the Fascist regime, the temporal framework for this special issue, they allude to the unfinished relations between Italy and Africa after the official end of the colonial empire.

As can be seen in Figure 5, the MUDEC display alluded to this multi-layered history by piling the manillas in a display case, a hoard of hundreds of objects that operate as a poignant illustration of Karl Marx's theory of the primitive accumulation of capital – giving material reality to the entwinement between economic expansion and colonial exploitation that Vigoni's collection too had revealed.

Figure 5. Detail of display case in room 3, MUDEC: ‘The Colonial Period: Looting and Despoliation in Africa’ (June 2019), photo courtesy of Elizabeth Marlowe.

As commodities traded through different networks and whose meaning was reframed multiple times over the course of their existence, the manillas reveal the shifting nature of material and visual culture and its interpretation over time. Indeed, on their own, objects such as the manillas can provide us with much information about their makers, circulation, and multiple uses – from personal adornment to currency to scrap metal. Yet, as visitors to MUDEC, we need to make an imaginative leap to reconstruct the embodied experience of using them – after all, as museum objects, these manillas cannot be handled, so we do not know how heavy, coarse, or cold they are to the touch. Mindful of this, Orsini and Antonini decided to pair the manillas display case with a video that visualises not only how they were used by some of their original wearers but also how they are cleaned and manipulated by MUDEC curators, as can be seen in Figures 6 and 7. The videos not only mediate our experience of the objects in question but also supplement it, providing knowledge on both the manillas’ contexts of use as well as on their afterlife as museum objects.Footnote 5

Figure 6. Detail of video in room 3, MUDEC: ‘The Colonial Period: Looting and Despoliation in Africa’ (June 2019), photo courtesy of Elizabeth Marlowe.

Figure 7. Detail of video in room 3, MUDEC: ‘The Colonial Period: Looting and Despoliation in Africa’ (June 2019), photo courtesy of Elizabeth Marlowe.

Like the Dogali brooch and the manillas, the focus of each of this special issue's articles are eloquent objects of the global history of Italian imperialism, tasked with shaping perceptions of the country's colonial past as well as of its post-colonial present. With their double identity as both objects and images, the anthropological masks, photo-albums and illustrated journals that are our authors’ case-studies operate as pathways for understanding the history of Italian colonialism during the Fascist regime as well as its visual and material afterlives. Paying attention to both visual and material culture allows our authors to centre and give voice to makers and consumers who are often overlooked by scholars because their lives are not well-represented in the written record – for example, the soldiers who fought Italy's colonial campaigns, the scientists who buttressed their racist ideology, the designers of the covers of the regime's magazines, or the journalists who shaped the memory of Fascist Ethiopia. Looking at colonial aesthetics as both images and objects makes it possible to begin to uncover the often overlooked negotiations between authoritative directives from above and other players, revealing the agency and subjectivity of makers, users, and consumers of culture – even under a totalitarian regime such as Italian Fascism.

Overview of this special issue

Investigating a diverse range of media forms, our four contributors unpack the circulation of colonial ideologies both in the peninsula and in Italy's occupied territories, during the Fascist regime and in its afterlife. Their articles show that images and objects narrate Italian colonialism in ways that are often complementary or alternative to those provided by textual sources.

By addressing the lived experience of colonialism, the articles gathered in this issue reconsider rapidly-changing mass-production technologies that visualised and materialised imperial hierarchies, among them photographs, illustrated magazines, and mass-produced advertisements. As image-objects that crossed lines of gender, class, race and geography and operated as sites of contact for producers and consumers of mass culture, our authors’ focus of study contributed to the construction of what Adolfo Mignemi called ‘a coordinated image of Empire’ (Mignemi Reference Mignemi1984). Our authors’ contributions, informed by a wide array of methodological approaches, unpack the ways in which the visual and material repertoire of Italian colonialism manifests ideological strategies peculiar to Fascism's imperial project.

This special issue opens with an article by Markus Wurzer, ‘The social lives of mass-produced images of the 1935–41 Italo-Ethiopian War’. Wurzer studies a series of albums created by German-speaking Italian citizens from the province of Bozen/Bolzano who participated in the invasion of Ethiopia. The albums made by these so-called ‘allogeni’ included privately produced images but also customised widely circulating propaganda and commercial photographs. By looking at the collecting practices of soldiers, Wurzer brings into focus the perspective of ordinary colonialists – complementing studies that focus on the official uses of photography during the Fascist regime. In particular, he re-evaluates the notion that these private photographic collections subverted narratives around the war produced from above. In his research, Wurzer found that they rather expressed a broad agreement with Fascist consensus, even when they were made by soldiers like the ‘allogeni’ who were considered second-class citizens by the Fascist state. Wurzer's article also casts light on the aftermath of colonial material culture, as some of the albums he studies are still kept in the family homes of these soldiers’ descendants. Wurzer thus takes into consideration the entire span of the ‘social lives’ of the albums he examines, from production to consumption to afterlife, thus revealing multi-generational negotiations of colonial memory among German-speaking Italians.

These questions also pervade Lucia Piccioni's essay, ‘Images of Black faces in Italian colonialism: mobile essentialisms’. Piccioni takes as her point of departure anthropologist Lidio Cipriani's face casts of African peoples – most often than not taken without the subjects’ consent and thus echoing the intrinsic violence of colonial relations and the complicity of scientific discourse in bolstering them. Piccioni tracks down the metamorphoses of Cipriani's casts in different media: from racist illustrations in the magazine La Difesa della Razza, to songs such as the infamous Faccetta Nera, to mass exhibitions such as the 1940 Mostra triennale delle terre italiane d'Oltremare. For Piccioni, the over-representation of African faces in Fascist mass culture reified and gave ontological consistency to what until then had been vague notions of racial difference. Drawing on theories on the agency of images, Piccioni demonstrates that the pervasiveness of racist depictions of African faces in the aftermath of the invasion of Ethiopia, as she puts it, ‘play[ed] an active role in the construction of political discourse’.

In ‘Colonies on the Cover: Italo Balbo's Libia’, Priscilla Manfren provides a detailed account of the visual programme of a prominent colonial illustrated magazine. Libia was published between 1937 and 1942 by ETAL (Ente Turistico ed Alberghiero della Libia), an agency created by Italo Balbo when he became Libya's governor. Manfren unpacks the ways in which this magazine, and most especially its covers, manifest Balbo's political and ideological priorities with regard to the colony he was in charge of administering. As Manfren shows, Balbo originally did not welcome his appointment as governor of Libya. Yet soon he came to relish this position, which allowed him to create a veritable ‘court’ of architects, artists, and intellectuals with whom he had already collaborated in his native city, Ferrara. They helped Balbo develop an image of Libya as an ideal tourist destination for Italians and non-Italians alike. Manfren unpacks the manifold aesthetics and subject matter included in their designs for Libia's covers, which aimed at providing an image of Libya as both modern and traditional, Roman and Arab, Italian and exotic. Manfren's focused analysis at the micro-level allows an in-depth inquiry into the mechanisms of consent for Fascist colonialism.

In the final contribution of the special issue, Elena Cadamuro moves from the Fascist period to its afterlife. Her article ‘The denial of shame. Representations and annual commemorations of the Ethiopian War in the news magazine Epoca (1950–60)’ challenges the received notion that the memory of Italian colonialism was repressed at least until the 1960s. By contrast, Cadamuro shows that this theme was alive in the Italian press in the previous decade too. Her focus of study is Epoca, most particularly how this ‘centrist and atlanticist magazine’ (in Cadamuro's reckoning) commemorated the Ethiopian war on the occasion of its twentieth (1955) and twenty-fifth (1960) anniversaries. Cadamuro addresses how the Fascist colonial past was framed and censored by unpacking Epoca's articles as iconotexts, examining their illustrations from an iconographical and iconological point of view. By probing which image of the Ethiopian war Epoca provided to its readers – especially by exaggerating the military equipment of the Ethiopians, and downplaying the belligerency of the Italians – Cadamuro shows how the Italy of the Economic Boom internalised, ‘silenced, misrecognised, and [did] not truly comprehend’ (in her words) its colonial past. In particular, Cadamuro explores the circulation of evidence of the use of poison gas: despite photographs attesting to Italy's use of chemical warfare in Ethiopia being already available, Epoca's texts briefly mentioned it but completely elided this evidence from its choice of photographs. Cadamuro's analysis demonstrates how news magazines stand out as significant markers in tracing the legacy and reception of Italian colonial crimes and their ideological underpinnings.

Future directions of research

As a whole, the essays in this issue all shed new light on the consensus-building strategies of Italian Fascist imperialism and we hope they will open further avenues of research. As a start, more work remains to be done on the visual and material culture of anti-colonial and anti-Fascist reactions in Italy (see Srivastava Reference Srivastava2018 on resistance during the Fascist regime; on anticolonialism in Liberal Italy see Rainero Reference Rainero1971; Belmonte Reference Belmonte2021, 127–158). Furthermore, we must be mindful that the shortage of studies on the first stages of Italian colonial history sways our reading of Fascist propaganda strategies in representing, exhibiting, collecting, and monumentalising imperialism.Footnote 6 Thus, the historiographical debate would also benefit from an expansion of the field of research to pre-Fascist and postcolonial Italy, looking at the multiple trajectories of Italian colonial occupation in East and North Africa as well in the Dodecanese, Albania, and Tientsin (China). Most current research on Fascist colonialism has so far focused on the male Italian experience; we hope that this issue will encourage scholars to delve further into images and objects produced by and for other constituencies: colonists and colonised women and children most especially. Moreover, a shift from Italian colonial materials to the wealth of artefacts produced in the occupied territories that respond to and react to colonialism would open a new productive line of research – one that is finally more feasible now that many colonial collections in Italy are again accessible in storerooms and museum displays.Footnote 7

However, a vivid academic discussion on colonial history and heritage is already present in Italy and has encouraged the rise of collaborative networks and research groups. Some of the scholars included in this special issue as authors or editors have an active role in these collaborative projects. At the University of Padua, Priscilla Manfren is part of the research group directed by Giuliana Tomasella working on Fascist colonial art and exhibitions. In 2019 Markus Wurzer founded (together with Daphné Budasz) the public history digital interdisciplinary project Postcolonial Italy – Mapping Colonial Heritage (https://postcolonialitaly.com/it/home-2/), cataloguing colonial remains in the public space of the Italian peninsula. Elena Cadamuro participates in the interdisciplinary research network CENTRA (Centre for the History of Racism and Anti-Racism in Modern Italy), based at the University of Genoa. In 2022 the Bibliotheca Hertziana–Max Planck Institute for Art History in Rome launched the research unit Decolonizing Italian Visual and Material Culture, coordinated by Carmen Belmonte and Tristan Weddigen, part of the interdisciplinary research network SPAZIDENTITA promoted by the École française de Rome. Breaking existing boundaries between neighbouring disciplines, these collaborative projects foreground scholarly conversations and participate in the wider public debate on the visual and material legacies of the Italian colonial project.

We hope that this issue will encourage scholars to produce new studies of the visual and material culture of Italian colonialism, providing effective critical tools for reading such dimensions of coloniality in the present. As Daniela Bleichmar and Vanessa Schwartz state, ‘we see the news more than we read it, historical fictions and documentaries play on screens small and large to enormous audiences; new museums dedicated to national and world heritage exhibit the past and visualize historical narratives primarily through combinations of objects and images’ (Bleichmar and Schwartz Reference Bleichmar, Schwartz, Bleichmar and Schwartz2019, 4). Therefore, it is urgent to reread colonial and postcolonial history through images and objects, exploring their life and afterlife in the longue durée. Images and objects are able to fold time (Nagel and Wood Reference Nagel and Wood2010, 13). They also include different temporalities in their afterlife and durability – the time when they are made and the multiple times when they are observed. Therefore, their survivance, repurposing and recontextualisation activate new meanings in the interplay between them and different beholders.

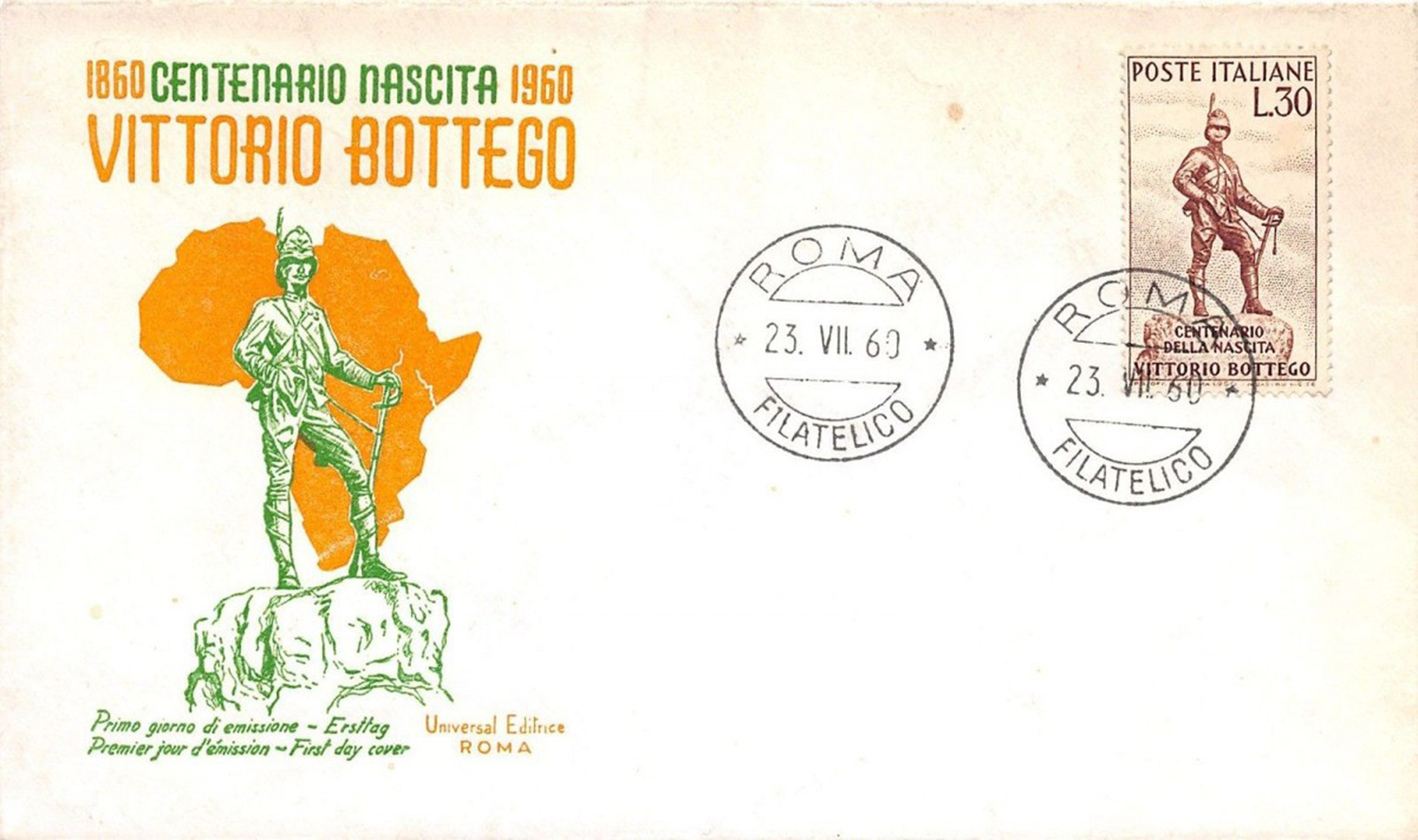

As a consequence, investigating images and objects requires that we cross temporalities and dismantle periodisation and chronologies, but at the same time allows us to pinpoint ruptures and continuities in colonial history. Framed as such, even a postage stamp, a small, mass-produced object, can provide several insights into Italian colonial and postcolonial memory. Issued in 1960, the stamp in Figure 8 visualises a colonial monument dedicated to Vittorio Bottego (1860–97), celebrated for his exploration of the Horn of Africa during the nineteenth-century Italian occupation. The city of Parma inaugurated the bronze monument by sculptor Ettore Ximenes in 1907, for the anniversary of his death (Figure 9). The celebration of Bottego as a colonial hero – wearing a colonial uniform and dominating the figures of two Gall warriors representing the Omo and Juba rivers – took place in a time of failure of Italian colonial ambitions following the defeat of Adwa. The issue of a postage stamp repurposing a monumental object evoking the nineteenth-century colonial enterprise in 1960 – precisely the year of Somalia's independence and the definitive closure of the Italian colonial presence in Africa – challenges once more the idea of a repression of the colonial past in postcolonial Italian memory.Footnote 8 Bottego's 1960 postage stamp reveals how everyday images and objects shaped the multiple memories of Italian colonialism, and their study allows a rereading not only of colonial history but also of postcolonial legacies.

Figure 8. Postage stamp memorialising Vittorio Bottego, 1960, private collection.

Figure 9. Ettore Ximenes, Monument to Vittorio Bottego, 1907, Parma. Foto Pisseri (studio), private collection.

In conclusion, we hope that Visual and Material Legacies of Fascist Colonialism will provide a starting point and methodological tools with which to interrogate the history of images and objects produced in the context of the Italian imperial project.

Acknowledgments

The guest editors would like to thank first and foremost Francesca Billiani for commissioning this special issue and for her valuable suggestions throughout the process of putting it together. They are also grateful to the authors for their commitment to Visual and Material Legacies of Fascist Colonialism and for their timely work; to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback that further improved the texts; and to the journal's general editors Milena Sabato and Gianluca Fantoni for their support and patience.

Competing interests

the authors declare none.

Carmen Belmonte is a Researcher at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – MPI, and the scientific coordinator of the research unit Decolonizing Italian Visual and Material Culture at the Bibliotheca Hertziana in Rome within the interdisciplinary research network SPAZIDENTITÀ co-funded by the École Française de Rome (2022–2026). She was awarded postdoctoral fellowships from the Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History, the American Academy in Rome, the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max Planck Institute and the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America at Columbia University, New York. Among articles and essays focusing on the visuality and materiality of Italian colonialism and on the legacy and memory of Fascism, she recently published the book Arte e colonialismo in Italia. Oggetti, immagini, migrazioni (1882–1906) (Collana del Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, Venice, Marsilio, 2021).

Laura Moure Cecchini is Assistant Professor (Ricercatore di tipo B) in the Department of Cultural Heritage at the University of Padua. She was Lauro de Bosis Postdoctoral Fellow at Harvard University and Associate Professor of Art and Art History at Colgate University. Her research focuses on the transnational legacies of Fascist visual and material culture. Her book Baroquemania: Italian Visual Culture and the Construction of National Identity, 1898–1945 (Manchester University Press, 2022) studies the cultural politics of the Baroque in Italian modernism. Her work has recently appeared in The Art Bulletin, Selva, MODOS, Third Text and Modernism/modernity. Laura's research has been supported by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Center for Italian Modern Art and The Wolfsonian-Florida International University, among other institutions.

Additional thematic bibliography on visual and material culture of Italian colonialism

Without any pretence of exhaustiveness, we have gathered here a preliminary bibliography (mostly in Italian and English) that complements the articles in this issue. We hope it can be a useful resource for the readers of Modern Italy who are interested in delving further into the material and visual culture of Italian colonialism.