Introduction

Sickness absence due to mental ill-health is still increasing in many Western countries. Common mental disorders (CMD), including depression, anxiety disorders, and stress-related disorders, are the most common diagnoses (OECD, 2012). The risk of long-term sick leave and recurring sick leave episodes is high for these conditions, and it places a great burden on individuals, employers, healthcare, and society at large (OECD, 2012, Andersen, Reference Andersen2010, WHO, 2017). The evidence for the effectiveness of interventions to improve return to work (RTW) in patients with mental ill-health is inconclusive (Nieuwenhuijsen et al., Reference Nieuwenhuijsen, Verbeek, Neumeyer-Gromen, Verhoeven, Bültmann and Faber2020, van Vilsteren et al., Reference Van Vilsteren, Van Oostrom, De Vet, Franche, Boot and Anema2015, Brämberg et al., Reference Brämberg, Åhsberg, Fahlström, Furberg, Gornitzki, Ringborg and Thoursie2024). However, improved collaboration and communication between stakeholders have been increasingly emphasized as important for a successful sick leave and rehabilitation process (Loisel and Durand, Reference Loisel, Durand, SCHULTZ and GATCHEL2005, Franche et al., Reference Franche, Cullen, Clarke, Irvin, Sinclair and Frank2005, Maiwald et al., Reference Maiwald, Meershoek, De Rijk and Nijhuis2014, Wynne-Jones et al., Reference Wynne-Jones, Mallen, Main and Dunn2010).

Interventions to support communication between sick-listed employees and different stakeholders have been developed in several settings (Karlson et al., Reference Karlson, Jönsson, Pålsson, Åbjörnsson, Malmberg, Larsson and Österberg2010, van Oostrom et al., Reference Van Oostrom, Van Mechelen, Terluin, De Vet, Knol and Anema2010, Tamminga et al., Reference Tamminga, De Boer, Bos, Fons, Kitzen, Plaisier, Verbeek and Frings-Dresen2012, Munir et al., Reference Munir, Kalawsky, Wallis and Donaldson-Feilder2013, Amin et al., Reference Amin, Stergiou-Kita and Jones2017, Hoefsmit et al., Reference Hoefsmit, Houkes, Boumans, Noben, Winkens and Nijhuis2016) but none as brief and simple as would be ideal for the primary healthcare setting, nor designed for the specific needs of patients with CMD. Primary healthcare is characterized by a heterogeneous patient group with a wide array of diagnoses and with limited time (approx. 15–30 min) per patient. During this short consultation, the GP’s primary focus is the medical issue, while work-related matters and sickness certification tend to be less prioritized (Nordling et al., Reference Nordling, Priebe, Bjorkelund and Hensing2020, Nordling et al., Reference Nordling, Jakobsson and Hensing2022).

Determining a person’s capacity to work and need for sick leave is a complex matter, especially in conditions like CMD where symptoms are often hard to observe and verify, and the effect on functioning is both fluctuating and highly individual (Bertilsson et al., Reference Bertilsson, Petersson, Östlund, Waern and Hensing2013, Bertilsson et al., Reference Bertilsson, Maeland, Löve, Ahlborg, Werner and Hensing2018, Dewa et al., Reference Dewa, Hees, Trojanowski and Schene2015). Research suggests that physicians make their assessment mainly based on clinical findings and the patient’s story, while their inquiry about the patient’s work situation is limited (Nordling et al., Reference Nordling, Priebe, Bjorkelund and Hensing2020, Wynne-Jones et al., Reference Wynne-Jones, Mallen, Main and Dunn2010). In addition, communication with the patient’s workplace is hard to achieve due to lack of time and channels for communication (Nordling et al., Reference Nordling, Priebe, Bjorkelund and Hensing2020, Wynne-Jones et al., Reference Wynne-Jones, Mallen, Main and Dunn2010), and the risk of breaching integrity (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Brown and Stewart2005, Wynne-Jones et al., Reference Wynne-Jones, Mallen, Main and Dunn2010). A survey among 4228 Swedish GPs showed that 9 out of 10 found contacts with sick-listed patients’ employers valuable for their work with sickness certification, but only 4 out of 10 had such contacts regularly (Nordling et al., Reference Nordling, Alexanderson, Hensing and Lytsy2021).

This study was part of the Capacity Note project where a brief communication facilitator was developed to support early and structured communication about mental health and RTW between the general practitioner (GP), the patient (on sick leave due to CMD), and the patient’s employer (Nordling et al., Reference Nordling, Jakobsson and Hensing2022). The presumed benefits of using the intervention were for GPs a facilitated assessment of work capacity and a better basis for the sickness certificate, for employers a better basis for decisions about work adjustments, and for patients a more active and individualised sick leave process. The aim of this study was to test whether this approach could work in the primary healthcare setting and whether it affected length of sick leave.

Material and methods

Study design

The study was designed as a non-blinded randomized pragmatic trial with a follow-up of 17 months. Pragmatic trials are used to test if an intervention works in real life and is performed in routine practice settings rather than under controlled and well-defined research conditions (Patsopoulos, Reference Patsopoulos2011). This is a common approach in primary healthcare trials and was in line with the theoretical assumptions underlying the design of the intervention (see below). The extended CONSORT guidelines for pragmatic trials (Zwarenstein et al., Reference Zwarenstein, Treweek, Gagnier, Altman, Tunis, Haynes, Oxman and Moher2008) guided the reporting of this study.

Setting and procedures

The universal sickness insurance scheme in Sweden covers all inhabitants. The first 14 days of sick leave among employed persons are covered by the employer (except for a reduction equivalent to one-day sick salary). From the 15th day, the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SSIA) administers benefits. The individual can certify him-/herself sick for 7 days. From day 8, a medical certificate, issued by a physician and stating a reduced capacity to work due to medical symptoms, disease, or injury, is needed. Sick leave can be issued for full- or parttime (25, 50, or 75%).

Patients with CMD are generally managed in primary healthcare, as is their sick leave (when needed). The primary healthcare is organized in a demand-supply organization. The demand side is public and tax-financed while the supply side can be either public or private. Patients enrol themselves to a primary healthcare centre (PHC) of their own choice. The primary healthcare is responsible for treatment and medical rehabilitation. The SSIA and the employer share the responsibility for vocational rehabilitation. The employer is responsible for making relevant workplace adjustments and facilitating the employee’s RTW. Swedish secrecy law prohibits the physician from contacting the employer without consent from the patient.

The study was carried out at public and private PHCs in the region of Västra Götaland in Sweden. There were several other primary healthcare research projects running in the region at the time and we were assigned a specific geographic area. Of the 28 PHCs in the area, four were involved in other research projects and six were considered too remote. The managers of the remaining 18 PHCs were contacted via e-mail with information about the study by either the head of the regions’ primary healthcare research and development centre (LN) or a GP active in both research and clinical work in the area (IMS). Five PHCs declined to participate and three did not respond. At the 10 PHCs that were interested, a meeting was held to further inform the PHC manager and the GPs about the study. These meetings were 30–60 minutes long, depending on what time span we were offered. All 10 PHCs accepted participation but due to a shortage of staff during the planned study period two could not participate (Figure 1). Characteristics of the eight participating PHCs are presented in Table 1. PHCs were financially compensated with 1100 SEK (approx. 100 EUR) per included intervention or control patient.

Figure 1. Recruitment and participant flow diagram. PHC = primary healthcare centre, GP = general practitioner, CAU = care as usual.

Table 1. Characteristics of the primary healthcare centres (PHCs) that participated in the study and their respective contributions

Before the study started, all physicians handling sickness certification at each PHC were randomized to being intervention or control physicians. This was done manually by a research assistant not otherwise involved in the project. Specialists and those not yet specialists were randomized separately to ensure similar levels of experience among intervention and control physicians. Due to the design of the intervention, blinding was not possible.

At the study start, a brief meeting (5–30 min, again depending on what was offered) was held with the GPs for notification of randomization results, a repetition of study procedures, and distribution of written material such as the Capacity Note (see Intervention) and inclusion/exclusion criteria. GPs who were not present at these meetings were approached with this information later, e.g., during a lunch break. Both intervention and control physicians received information about the purpose, structure, and logistics of the intervention, but the full content was disclosed only to intervention GPs.

Participants and recruitment

Eligible participants were employed women and men aged 18–64 years who consulted a GP due to common mental disorders (CMDs) and became part- or full-time sick-listed or had been so for no longer than four months. A current health status permitting decision-making about participation in the study was also required. Patients with severe psychiatric conditions, suicide risk, or severe somatic disease (e.g., cancer with secondary anxiety) were excluded.

Participating GPs were responsible for identifying eligible study participants during consultations and referring them to a research assistant who gave oral and written information and asked for informed consent. The research assistant was present at the PHC daily. After a few weeks, it became clear that many follow-up consultations concerning sick leave were telephone consultations and we added the possibility to recruit patients and use the intervention over the phone. Patients recruited this way were contacted by the research assistant after the consultation and then came to the PHC to give written consent.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of a brief and structured way to discuss issues related to the patient’s current health and work situation using the Capacity Note – a paper form with three sections covering these topics; see Figure 2 for examples of questions in each section. The Capacity Note was used in three steps: 1) patient and GP discussing and filling in part 1 about work situation and part 2 about work capacity, 2) patient and employer discussing and filling in part 3 about work accommodations, and 3) follow-up at the next patient–GP contact. The intervention intended to facilitate a dialogue and information transfer between the stakeholders, thereby supporting their decision-making process in the sick leave and rehabilitation process. For more details, see below and in Nordling et al. (Reference Nordling, Jakobsson and Hensing2022).

Figure 2. Examples of questions in each part of the Capacity Note.

Theoretically, the intervention was inspired by the concept of agency, understood as the individual’s will and capacity to act independently (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1977). Agency theory states that we accommodate social practice in relation to our position in a certain social context. Individual agency can be hampered by structural factors such as legislation, employment conditions, accessibility of information, and the social context at work (Ståhl et al., Reference Ståhl, Karlsson, Sandqvist, Hensing, Brouwer, Friberg and Maceachen2021, Danielsson et al., Reference Danielsson, Elf and Hensing2019, Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1977). Qualitative studies exploring patients’ experiences of becoming sick-listed suggest that after the initial emotional reactions a period of activity follows, which is later replaced by passivity and waiting for others to make decisions or take initiatives (Mårtensson and Hensing, Reference Mårtensson and Hensing2012, Danielsson et al., Reference Danielsson, Elf and Hensing2019). Agency can also be negatively affected by CMD symptoms such as worries, difficulties in making decisions and lack of energy and/or motivation (Bertilsson et al., Reference Bertilsson, Petersson, Östlund, Waern and Hensing2013, Danielsson et al., Reference Danielsson, Bertilsson, Holmgren and Hensing2017). Here, the GP has an important role in supporting the patient’s agency by providing treatment, information, and emotional support. The intervention was designed to strengthen the patient’s agency by making the patient more active in his/her sick leave process and by facilitating the GP’s assessment and subsequent recommendations. An important theoretical departure was to follow if patients managed to use the Capacity Note without too much involvement of clinicians or researchers.

Intervention group

In the intervention group, parts 1 and 2 of the Capacity Note were discussed and filled in by the patient and his/her GP during the consultation. The patient was then instructed by the GP to bring the Capacity Note to his/her manager for a joint discussion of part 3. The completed Capacity Note was to be sent back by the patient to the PHC, where it was added to the patient’s medical record and could be used for follow-up. There were no reminders or other contacts from the research team to influence the patients’ use of the Capacity Note. Neither did we check whether the Capacity Note was used for follow-up by the GP. In addition to using the Capacity Note, patients in the intervention group received care as usual. For patients with CMD in primary healthcare, this includes psychologist/counsellor contact, pharmacological treatment and/or referral to an occupational therapist, physiotherapist, and/or rehabilitation coordinator.

Control group

In the control group, patient and GP filled in part 1 of the Capacity Note during the consultation. This was done to enable comparison of patient demographics. The Capacity Note was then put aside, and the patient received care as usual (as described above).

Data and outcomes

Participant characteristics

Data on age, sex, and occupation were collected from part 1 of the Capacity Note. Occupations were classified as skilled (> two years of college or university education) or unskilled (Statistics Sweden, 2012).

Sickness absence

Sick leave data were obtained from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency’s database Micro Data for Analysing the Social insurance (MiDAS). The database does not contain data on current employment but a reduction in or discontinuation of registered sickness absence days was used as a proxy for RTW. Outcomes of interest were time until full RTW, sick leave status at the end of follow-up, number of sick leave episodes during follow-up, and number of gross sick leave days at 6, 12, and 17 months after inclusion. A follow-up time of 17 months was chosen as it was considered long enough to reveal the sustainability of RTW but short enough to limit the effect of other factors than the intervention on the outcomes.

Feasibility

To assess the feasibility of the intervention, the following parameters were of interest: number of potentially eligible patients who were asked to participate, number of eligible patients who accepted participation, reasons for not participating, drop-out rate, and level of adherence to study protocol. This data were collected continually at each participating PHC using local sick leave registers and study logbooks. Patients who declined participation at either GP or research assistant were asked to provide (voluntarily) their age, sex, occupation, and reason for not participating.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics of the study sample. Group differences in baseline characteristics, number of sick leave episodes during follow-up, and sick leave status at the end of the follow-up were analysed with the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Full RTW was defined as having no registered sickness absence for at least four weeks. Time until full RTW, measured as number of days from date of inclusion in the study to full RTW, was calculated using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and survival curves for the groups were compared with the log-rank test. The number of gross sick leave days at 6, 12, and 17 months of follow-up was calculated using the Mann–Whitney U test since the data during these follow-up times was not normally distributed. Only sickness absence due to CMD was analysed. Statistical significance was considered as a two-sided p-value <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 16 and IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.

Results

Recruitment

Data collection started in March 2018 and ended in Sept 2019 due to time constraints. Initially, the study periods were short, 2–5 weeks, and the study ran at one PHC at a time. In the end, to increase recruitment, the study ran continuously at two of the PHCs for 3 and 5 months respectively but with only a limited number of GPs active in recruiting patients.

To roughly estimate the number of potentially eligible patients, each participating PHC’s local sick leave register was checked at the start of their respective study period. Of the total number of sick leave cases at each PHC, 55% (mean) were due to CMD and of these, 37% (mean) were shorter than 4 months. The pattern was similar at all PHCs and can be illustrated with the numbers from PHC 7: a total of 145 patients were on sick leave, 72 cases were due to CMD, and 26 cases were shorter than four months. Considering in- and outflow, the total number of potentially eligible patients during the study (65 weeks) was calculated to be about 500 patients. The GPs identified 99 patients as eligible for participation. Of these, 64 accepted participation: 33/58 (57%) in the intervention group and 31/41 (76%) in the control group (Figure 1). Reasons for not participating are presented in Table 2. Six patients were excluded as they did not have an employer. In total, 58 patients were included in the study. Two intervention patients dropped out, leaving a study population of 56 participants (28 in each group) (Figure 1). As far as we know, 14 (50%) of the intervention patients completed the intervention, i.e. discussed the Capacity Note with their manager and returned it to the PHC.

Table 2. Stated reasons for declining participation in the study among patients identified as eligible by an intervention or control physician

Participant characteristics

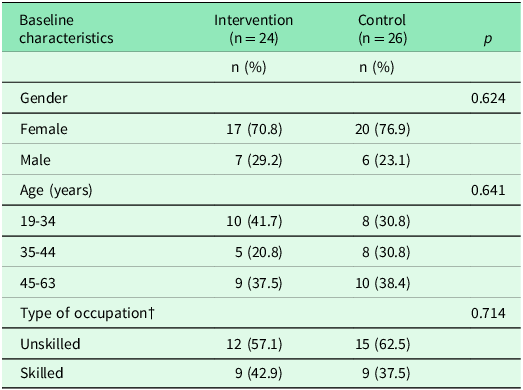

Six individuals were excluded from the data analysis (see Figure 1) and the final sample consisted of 50 participants: 24 in the intervention group and 26 in the control group. Most participants were women (intervention 71%; control 77%) and worked in unskilled occupations (intervention 57%; control 63%), with no statistically significant differences between groups (Table 3).

Table 3. Baseline characteristics of study participants (n = 50) in intervention and control groups, respectively, and analysis of group differences

†Five individuals (intervention, n = 3; control, n = 2) had missing information on type of occupation.

Sickness absence

The sickness absence patterns were similar in intervention and control groups, with no statistically significant group differences for any of the outcomes.

Time until full return to work

The median time from inclusion in the study to full RTW was 102 days in intervention group and 90 days in control group (χ2 =0.00, df=1, p=0.99) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier curves for time (days; median) to full return to work in intervention and control groups, respectively.

Sick leave status at end of follow-up

In the intervention group, 19 (79.2%) participants were not on registered sick leave at the end of follow-up, while 5 (20.8%) were still on full-time sick leave. In the control group, 22 (84.6%) participants were not on registered sick leave at the end of follow-up, 1 (3.9%) was on part-time sick leave, and 3 (11.5%) were on full-time sick leave.

Number of sick leave episodes during follow-up

Most participants had only one sick leave episode during follow-up (intervention, 79%; control, 77%) and the rest had two episodes (intervention, 21%; control, 23%).

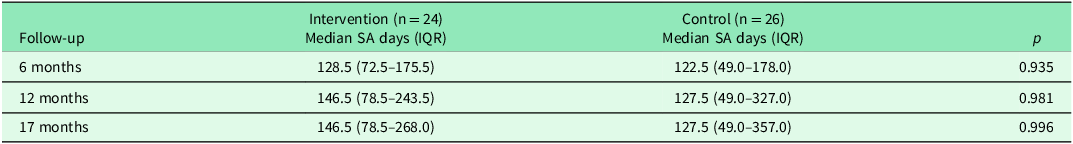

Number of gross sick leave days at 6, 12 and 17 months after inclusion

No difference was found between the groups in the median number of registered gross sick leave days at 6, 12, and 17 months (Table 4). The median number of days did not increase after 12 months in either of the groups.

Table 4. Comparison of registered gross sickness absence days in intervention and control groups at 6 months, 12 months, and 17 months follow-ups

SA, sickness absence; IQR, Interquartile range.

Discussion

This study tested a brief intervention to support communication about work capacity in patients with CMD. We found no differences between intervention and control patients in any of the outcome measures of sickness absence. Despite several measures to facilitate recruitment of patients, our sample was too small. Further studies with larger samples are needed to fully explore the intervention and its effect on sick leave. Some of the lessons learned from this study will be discussed below and can contribute to a more appropriate study design for future studies.

Recruitment of PHCs

Studies in primary healthcare are usually designed as pragmatic trials. Such trials have higher external validity than randomized controlled trials, which are characterized by high internal validity. However, a drawback of pragmatic trials is that to reach even small significant differences between intervention and controls, the number of participants must be very high (Patsopoulos, Reference Patsopoulos2011). This is admittedly difficult in primary healthcare studies (van der Wouden et al., Reference Van Der Wouden, Blankenstein, Huibers, Van Der Windt, Stalman and Verhagen2007, Bower et al., Reference Bower, Wilson and Mathers2007). Barriers to recruitment can be related to both the individual GP and the context.

GPs have in previous research expressed their frustration with management of sick leave (Letrilliart and Barrau, Reference Letrilliart and Barrau2012) especially in relation to mental health problems (Nilsing et al., Reference Nilsing, Soderberg, Bertero and Oberg2013), and we received several positive comments about the importance of our study. Still, it was surprisingly difficult to recruit PHCs and engage GPs, reflecting the fact that Swedish primary healthcare is a strained organization with a shortage and high turnover of staff (The Swedish Agency for Health and Care Services Analysis., 2020).

Recruitment of patients

Recruitment of study participants was slow, and we had to make adjustments and extend the inclusion period. The number of potentially eligible patients at each PHC was lower than expected, being one reason for the slow inclusion rate. In addition, factors such as having a planned contact/visit with the GP during the PHC’s study period played a role. Moreover, as seen in other studies on RTW, recruiting in the early stages of sick leave can be problematic (van Oostrom et al., Reference Van Oostrom, Van Mechelen, Terluin, De Vet, Knol and Anema2010, Hoefsmit et al., Reference Hoefsmit, Houkes, Boumans, Noben, Winkens and Nijhuis2016, Keus van de Poll et al., Reference Keus Van De Poll, Nybergh, Lornudd, Hagberg, Bodin, Kwak, Jensen, Lohela-Karlsson, Torgén and Bergstrom2020). Patients may have already planned for or started their RTW process, which may reduce motivation to participate/recruit. It is also a period of uncertainty to some degree where both patient and GP might choose ‘watchful waiting’ before more active measures.

We chose short study periods at each PHC to reduce the threshold for PHCs to participate and to keep up motivation among the GPs (Hange et al., Reference Hange, Björkelund, Svenningsson, Kivi, Eriksson and Petersson2015). However, it may have led to a lack of confidence and familiarity among GPs regarding study procedures. The rather short information meetings, due to the pressured working situation at participating PHCs, may have further contributed to this. In the end, study periods were longer, but this did not increase the pace of recruitment. We did our best to limit the burden on the GPs. The administrative burden for the users, and the PHCs, was kept to a minimum. Still, the handling of CMD and sick leave is time-consuming, leaving less time for presenting the study, which may have been a barrier for GPs (Arends et al., Reference Arends, Bültmann, Shaw, Van Rhenen, Roelen, Nielsen and Van Der Klink2014, Mason et al., Reference Mason, Shaw, Wiles, Mulligan, Peters, Sharp and Lewis2007). Some GPs also made comments indicating that they found their patients too vulnerable to participate in research, in line with other GPs’ experiences of mental health research in primary care (Mason et al., Reference Mason, Shaw, Wiles, Mulligan, Peters, Sharp and Lewis2007). Further, it is possible that the subjective assessment of ‘the patient’s readiness to participate’ caused uncertainties among GPs, resulting in asking fewer patients. Arends et al., (Reference Arends, Bültmann, Shaw, Van Rhenen, Roelen, Nielsen and Van Der Klink2014) found that occupational physicians preferred distinct inclusion criteria and were more willing to recruit patients with a positive attitude and enough energy to participate (Arends et al., Reference Arends, Bültmann, Shaw, Van Rhenen, Roelen, Nielsen and Van Der Klink2014). Lastly, there was little pressure on or incentive for the individual GP to engage in the project. Asking the GPs about potential barriers before the study start might have identified further barriers that could have been addressed.

Most of the patients asked to participate accepted, and the drop-out rate was very low, indicating that the intervention was acceptable. Half of the intervention patients completed the intervention, i.e. discussed the Capacity Note with their employer and returned the completed Capacity Note to the GP, which can be considered good given the highly pragmatic approach. Other studies in this patient group and involving several stakeholders have reported much lower adherence (Vlasveld et al., Reference Vlasveld, Van Der Feltz-Cornelis, Adèr, Anema, Hoedeman, Van Mechelen and Beekman2013). However, it also suggests that there were barriers to its use. In the qualitative evaluation of the Capacity Note, we found that managers’ lack of time and/or willingness to use the Capacity Note with their employee was one potential barrier (Nordling et al., Reference Nordling, Jakobsson and Hensing2022). Another was the patients’ reluctance to discuss these matters with their manager. The latter was a common reason for not participating in the present study and was expected given the stigma surrounding mental health (Thisted et al., Reference Thisted, Labriola, Nielsen, Jul Håkonsen and Bjerrum2020, Dewa et al., Reference Dewa, Van Weeghel, Joosen and Brouwers2020, Mangerini et al., Reference Mangerini, Bertilsson, De Rijk and Hensing2020). Also, patients were in an early phase of their sick leave, often associated with high levels of stress, and contacting the employer may have been perceived as a too-stressful task at this stage of the process (Noordik et al., Reference Noordik, Van Der Klink, Geskus, De Boer, Van Dijk and Nieuwenhuijsen2013).

Agency as a theoretical departure

The study design emphasized the responsibility of the patient to bridge the lack of information between the GP and the employer. The decision to let the patient take this role was based on agency theory, which claims that people are willing and capable to act and take responsibility in their own lives (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1977). The intervention aimed to strengthen the patient’s agency and own activity in relation to RTW, which has been described in earlier qualitative studies as important for patients (Mårtensson and Hensing, Reference Mårtensson and Hensing2012, Danielsson et al., Reference Danielsson, Elf and Hensing2019). Thus, we did not remind or urge patients to contact their employer; it was entirely a decision for the patients. However, it seems that for some patients this was not a suitable approach, they needed more support.

Sickness absence and RTW in patients with CMD

Systematic reviews on interventions to improve RTW for patients with mental ill-health show that intervention patients, in general, have a faster first RTW but the effect decreases during the first year, meaning that the RTW is not sustainable (Nieuwenhuijsen et al., Reference Nieuwenhuijsen, Verbeek, Neumeyer-Gromen, Verhoeven, Bültmann and Faber2020, van Vilsteren et al., Reference Van Vilsteren, Van Oostrom, De Vet, Franche, Boot and Anema2015). We chose a long follow-up time to see if RTW was stable. Most participants in the study had returned to work at the end of follow-up and had only one sick leave episode, indicating a sustainable RTW. However, we found no significant differences between the two groups. This is most likely explained by the small sample size. In addition, only half of the intervention patients completed the intervention which makes comparison of the groups more difficult.

Strengths and limitations

This study took a novel approach by enabling communication between GPs and patients’ employers by engaging the patient. This approach has not, to our knowledge, been tested before. It is also novel in the sense that the intervention is not a set method or guideline, but rather a tool to support the GPs in their own subjective assessment of the patient (Mason et al., Reference Mason, Shaw, Wiles, Mulligan, Peters, Sharp and Lewis2007, Nordling et al., Reference Nordling, Priebe, Bjorkelund and Hensing2020).

The most important limitation of the study was the small sample size, which prevented us from reaching any conclusions about the effect of the intervention on sickness absence. Another limitation is the risk of contamination. Even though GPs work rather individually they may have discussed the intervention during breaks. This could have been avoided by randomisation at PHC level. Furthermore, it is possible that control physicians gave work-related questions more consideration than usual after being informed about the study and filling in part 1 of the Capacity Note with their patients. These potential sources of bias must be addressed in a future study. Other areas that would need consideration in the design of a new trial are requesting more time for information about the study, optimal length of study periods and level of pragmatism. A more controlled trial might increase recruitment and level of adherence, making an effective evaluation possible, but would to some extent violate the agency approach. Finally, in a controlled trial, the randomization is expected to take care of possible differential distributions of factors of importance for the outcome. In this study, possible factors could be variations in type of CMD, earlier episodes, intensity of symptoms, comorbidity etc. We did not gather detailed information through medical journals or by interviewing participants. In a future study, this could be an advantage even if the sample size is larger.

Conclusions

This pragmatic trial tested the Capacity Note – a brief intervention to support early communication between GP, patient, and employer to promote RTW among primary healthcare patients with CMD. Due to the small sample size, we could not determine whether the intervention was an effective way to reduce length of sick leave. The recruitment rate was negatively affected by suboptimal research conditions in Swedish primary healthcare. Overall, the intervention seems feasible, but the vulnerability of the patient group calls for individualized assessments. The agency approach may not be suitable for all patients; some patients may need additional support. The findings from this study provide valuable input for any future studies on the current intervention as well as for other studies on stakeholder communication about mental health and work.

Author contributions

PN was involved in study design, data collection, and interpretation of results, and drafted the manuscript. CN performed the data analyses and interpreted the results. LN and IMS were involved in study design and recruitment of PHCs. MEHL and CB were involved in study design. GH came up with the research idea, designed the study, and was responsible for all parts of the project. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding statement

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (ref nr. 2013-02216 and 2016-07419).

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg, Sweden (ref nr. 1115-17). Participation was based on written informed consent. All participants were informed that the decision to participate or not would not influence their care and that withdrawal from the study was possible at any time.