Introduction

Bullying has been defined as intentional and repeated aggressive behaviours that occur in power and imbalanced interpersonal relationships (Whitney and Smith, Reference Whitney and Smith1993; Olweus, Reference Olweus1994). Bullying is a highly stressful experience and victims can have numerous negative outcomes (Duong and Bradshaw, Reference Duong and Bradshaw2014). Peer bullying experienced by adolescents is correlated with severe mental health problems – including suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, non-suicidal self-injury, depression and anxiety – and can have long-term detrimental life consequence (Klomek et al., Reference Klomek, Marrocco, Kleinman, Schonfeld and Gould2007; Drydakis, Reference Drydakis2019; Li et al., Reference Li, Zheng, Tucker, Xu, Wen, Lin, Jia, Yuan and Yang2019; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Liu, Cao, Duan, Wen, Zhang, Xu, Lin, Xue and Lu2020). Due to the marginalised sexual orientation, lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) adolescents are more likely to face noticeable challenges and adverse experiences, including the victim-bully cycle (Button et al., Reference Button, O'Connell and Gealt2012).

Bullying in sexual minority individuals

Studies across different countries have demonstrated that sexual minorities tend to be victims of verbal, physical and social bullying (Birkett et al., Reference Birkett, Espelage and Koenig2009; Robinson and Espelage, Reference Robinson and Espelage2012; Collier et al., Reference Collier, Van Beusekom, Bos and Sandfort2013; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Espelage and Rivers2013; Duong and Bradshaw, Reference Duong and Bradshaw2014). A previous meta-analysis showed that identifying as a sexual minority is a risk factor for suffering from bullying at school (Moyano and del Mar Sánchez-Fuentes, Reference Moyano and del Mar Sánchez-Fuentes2020). Researchers have consistently found that homophobic bullying is linked to negative mental health outcomes (Espelage et al., Reference Espelage, Valido, Hatchel, Ingram, Huang and Torgal2019; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Zhu, Gillespie, Wang, Gao, Xin, Qi, Ou, Zhong and Zhao2019). Much of the literature has focused on the experiences of sexual minority adolescents being bullied, while studies on sexual minority adolescents' participation in bullying are scarce. Previous research on the victim-bully cycle in middle school indicates that the relationship from bully to victim was reciprocal (Ma, Reference Ma2001). Bully-victims can be defined as an individual who was a victim of bulling who then in turn reciprocates and bullies others (Swearer et al., Reference Swearer, Song, Cary, Eagle and Mickelson2001). Research on the victim and bully roles at school has found that the victim role was unstable and that the bully role was only moderately stable (Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Korn, Brodbeck, Wolke and Schulz2005). Many studies have suggested the roles oscillate between bully and victim (Olweus, Reference Olweus1994; Slee, Reference Slee1995; Swearer et al., Reference Swearer, Song, Cary, Eagle and Mickelson2001). The victim-bully cycle can be explained by social learning theory; the victims' bullying behaviours could be a socially learned behaviour as a response to coping with the situation (Ma, Reference Ma2001). Bullying research has also found that some of the most extreme victims are also among the most aggressive of bullies (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Kusel and Perry1988). In addition, sexual minority youth who experience school bullying are more likely to engage in aggressive behaviours such as physical fights (Duong and Bradshaw, Reference Duong and Bradshaw2014). It is important to note that those who take on the role of both the victim and bully may be at the highest risk for depression and anxiety (Swearer et al., Reference Swearer, Song, Cary, Eagle and Mickelson2001).

Bullying and mood problems

Research has shown that victims of bullying are at risk of mood disorders (Kochenderfer-Ladd and Skinner, Reference Kochenderfer-Ladd and Skinner2002; Tenenbaum et al., Reference Tenenbaum, Varjas, Meyers and Parris2011). There is ample documentation of the sexual minority population being at risk for depression and anxiety (D'augelli and Grossman, Reference D'augelli and Grossman2001; Meyer, Reference Meyer2003; Cochran and Mays, Reference Cochran and Mays2009; Bostwick et al., Reference Bostwick, Boyd, Hughes and McCabe2010; Chakraborty et al., Reference Chakraborty, McManus, Brugha, Bebbington and King2011; Marshal et al., Reference Marshal, Dietz, Friedman, Stall, Smith, McGinley, Thoma, Murray, D'Augelli and Brent2011; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Reference Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Barkan, Muraco and Hoy-Ellis2013). Considering that sexual minority individuals have a higher likelihood of being bullied and a higher risk of having mood problems, bullying and mood disorders are likely to be prevalent in sexual minority adolescent at schools. Although the role of bullying within hypomania is not clear, a previous study suggests that bullying victimisation may increase the vulnerability of developing psychotic symptoms which could result in further hypomanic symptoms (Trotta et al., Reference Trotta, Di Forti, Mondelli, Dazzan, Pariante, David, Mule, Ferraro, Formica, Murray and Fisher2013). Sexual minority identity has been associated with psychosis (Pakula and Shoveller, Reference Pakula and Shoveller2013; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Smith, McDermott, Haro, Stickley and Koyanagi2019), and researchers propose that stressful life events, such as bullying victimisation, may function as part of the underlying mechanism that results in hypomania (Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Smith, McDermott, Haro, Stickley and Koyanagi2019).

Coping strategies and bullying

Many studies have investigated the association between coping strategies and bullying (Varjas et al., Reference Varjas, Meyers, Meyers, Kim, Henrich and Tenebaum2009; Tenenbaum et al., Reference Tenenbaum, Varjas, Meyers and Parris2011). A previous longitudinal study in the USA found that bullying was more persistent for victims who applied negative coping strategies (i.e. fought back) than those who applied positive coping strategies (i.e. having a friend help) (Kochenderfer and Ladd, Reference Kochenderfer and Ladd1997). Researchers have indicated that victims of bullying generally found that the implementation of coping strategies was not effective in solving their problems (Tenenbaum et al., Reference Tenenbaum, Varjas, Meyers and Parris2011). The application of adaptive coping strategies may help to prevent future bullying and victimisation (Varjas et al., Reference Varjas, Meyers, Meyers, Kim, Henrich and Tenebaum2009). Sexual minority adolescents with effective coping strategies are also less likely to experience adverse events such as being marginalised and being bullied (Kiperman et al., Reference Kiperman, Varjas, Meyers and Howard2014).

Hypothesis

To the best of our knowledge, no existing published research has investigated the associative variables on the interaction between bullying others and being bullied among sexual minority adolescents. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the influence of the sex orientation on bullying and being bullied through the mediation of coping strategies and mood states. It is hypothesised that engaging in positive coping strategies could reduce the risk of being bullied. Moreover, previous studies have noted that sex difference also leads to adolescents applying different coping strategies in response to bullying (Naylor et al., Reference Naylor, Cowie and Rey2001). Thus, the current study will assess the influence of sex together with the influence of the sexual orientation as part of the bullying mechanism within the victim-bully cycle. This study also assessed the different odds ratio of sexual minority groups in comparison to heterosexual adolescents for a variety of bullying-related behaviours, in order to examine the disparities among the sexual minority groups.

Methods

Participants

Data were collected from 18 public secondary schools in Suzhou, a medium-size metropolitan city in China. Schoolteachers aided in the recruitment of subjects and it was made clear to potential subjects that participation was voluntary, and there were no adverse consequences for refusing to participate or for later if they chose to withdraw. A total of 12 354 questionnaires were completed and returned and the response rate was 83.2%. The study design and study participants have been described in a previous publication (Duan et al., Reference Duan, Duan, Li, Wilson, Wang, Jia, Yang, Xia, Wang, Jin, Wang and Chen2020). All students (6688 boys and 5666 girls) answered the question about their birth-assigned sex; however, there were 43 boys and 73 girls who did not specify to which sex they were attracted to and were therefore excluded from further analysis. As such, the sample in the analysis consisted of 6625 birth-assigned boys (M age = 14.94, s.d. = 1.48) and 5593 birth-assigned girls (M age = 14.95, s.d. = 1.48).

The student's sexual orientation was measured by two questions (Denny et al., Reference Denny, Lucassen, Stuart, Fleming, Bullen, Peiris-John, Rossen and Utter2016): ‘What was your biological sex assigned at birth? (choose from male or female)’ and ‘Which sex are you attracted to? (choose from male, female, both, and none)’. Students were categorised into six groups based on their birth-assigned sex and sexual: Those boys and girls who were attracted to the opposite sex were classified as opposite-sex-attraction-boys and opposite-sex-attraction-girls, respectively. Birth-assigned males attracted to other males were categorised as same-sex-attraction-boys, while birth-assigned females attracted to females were categorised as same-sex-attraction-girls. Birth-assigned boys who reported being attracted to both sexes were designated as both-sex-attraction-boys and birth-assigned girls attracted to both sexes as both-sex-attraction-girls (Denny et al., Reference Denny, Lucassen, Stuart, Fleming, Bullen, Peiris-John, Rossen and Utter2016). As Fenaughty et al. (Reference Fenaughty, Lucassen, Clark and Denny2019) point out, the choice of ‘to neither males nor females’ was not a particular measure of asexuality. Instead, we categorised the 2625 boys and 2395 girls who reported attracted to neither male nor female as sexual-undeveloped-boys and sexual-undeveloped-girls, because they are more likely to not yet experience sexual due to their young age rather than identifying as asexual. We believe these groups have meaningful differences, and a similar method of grouping among Chinese adolescents has been used to in a previous study (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Li, Guo, Gao, Xu, Huang, Deng and Lu2018).

Measures

The Chinese Trait Coping Style Questionnaire

The Trait Coping Style Questionnaire (TCSQ) was used to measure positive and negative coping styles among the adolescents. There were 20 items, with ten items assessing each sub-scale. One example for positive coping was ‘I focus on the positive side and reappraise the situation’; and one example for negative coping was ‘If I had a confrontation with someone, I would cut the communication with the person for a long time’. Responses were rated on a 1–5 Likert scale from 1 (not me at all) to 5 (I do things completely this way). A higher composite score indicates a higher inclination to adopt the positive or negative coping style, respectively. The Cronbach's α was 0.85 for the positive coping style sub-scale, and 0.88 for the negative coping style in this sample.

The Patient Health Questionnaire

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to measure the severity of depressive symptoms. There were nine items (e.g. ‘Little interest or pleasure in doing things’). Participants were asked to rate how often they had been bothered by any of the problems over the previous 2 weeks on a 0–3 point scale, where 0 = Not at all to 3 = Nearly every day. The Cronbach's α was 0.93 in this sample.

The 32-item Hypomania Checklist Chinese Version

The Chinese version of the Hypomania Checklist (HCL-32) was used to measure the level of hypomania in the adolescents. Participants were asked to choose yes or no on 32 statements about when they were in a state of ‘high spirit’. One example was ‘you are more talkative’. The Cronbach's α was 0.87 in this sample.

The Generalised Anxiety Disorder Screener

The Generalised Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) , which was previously validated in the general population, was used to measure anxiety symptoms; there are seven items (e.g. ‘worrying too much about different things’). Similar to the PHQ-9, participants were asked to report based on the previous 2 weeks' experiences, rated on a 0–3 point scale, where 0 = Not at all to 3 = Nearly every day. The Cronbach's α was 0.94 in this sample.

Frequency of being bullied at school

The frequency of being bullied at school was measured by five items. Participants were asked to rate their experience in the past academic year on a 1–4 point scale. Response options for this question were 0 = never, 1 = sometimes (1–2 per month), 2 = often (1–2 per week) and 3 = every day. One example was ‘Were you afraid of being kicked, pushed, or beaten at school?’ The total score of being bullied was calculated and the range of the composite score was between 0 and 15, with a higher score indicating a higher frequency of being bullied at school in the past academic year. The Cronbach's α was 0.68 in this sample. In the multinomial analyses, ratings of 1, 2 and 3 for each item were further grouped as a ‘yes’ response to the experience, in contrast to those who had not experienced bullying at school.

Frequency of bullying others at school

The frequency of bullying others at school was measured by five items. Participants were asked to rate their behaviours in the past academic year on a 1–4 point scale. Response options for this question were 0 = never, 1 = sometimes (1–2 per month), 2 = often (1–2 per week) and 3 = every day. One example was ‘Have you kicked, pushed, or beaten others at school?’ The total score of being bullied was calculated and the range of the composite score was between 0 and 15, with a higher score indicating a higher frequency of bullying others at school in the past academic year. The Cronbach's α was 0.66 in this sample. In the multinomial analyses, ratings of 1, 2 and 3 for each item were further grouped as a ‘yes’ response to the experience, in contrast to those who had experienced bullying at school.

Analysis

All analyses were carried out using R software Mac version 3.6.1. Total numbers and valid percentages were calculated for each sexual orientation group. Given the large sample size of the survey, p < 0.01 was taken to indicate statistical significance in all analyses. To assess the difference in measured variables among the sex and sexual attraction groups, a MANOVA was conducted. To assess the increased risk of being bullied and bullying others, in association with different groups, a series of multinomial regression were conducted. To assess the psychological mechanism behind the association between sexual orientation and the frequency of being bullied as well as bullying others, a structural equation model (SEM) was constructed using R Lavaan package using negative and positive coping, hypomanic behavioural pattern, anxiety and depression as the mediators. The analysis incorporated several regression analyses simultaneously, also allowing correlations between theoretically related variables; in particular: negative and positive coping, anxiety and depression, as well as the frequency of being bullied and bullying others.

Results

The means and s.d.s of the variables used in the study by sexual attraction groups are shown in Table 1. A 2 × 4 MANOVA was conducted to test the potential effect of sex and sexual on all measured variables, including being bullied, bullying others, positive and negative coping, hypomania, anxiety and depression. There was a significant main effect of sex, F (7, 10799) = 44.48, p < 0.001, Wilks' Λ = 0.97, partial η 2 = 0.03, a significant main effect of sexual, F (21, 31009) = 27.86, p < 0.001, Wilks' Λ = 0.95, partial η 2 = 0.02, and a significant main interaction of sex and sexual, F (21, 31009) = 6.04, p < 0.001, Wilks' Λ = 0.98, partial η 2 = 0.01. As the interaction term was significant, follow-up post hoc comparisons were done by comparing the eight sexual groups. The results are summarised in Fig. 1, which indicates the estimated mean (the mid-point) and 95% confidence interval (the bars extended from the mid-point) for each group on all the measured variables. Any two groups with non-overlapping bars in each panel of the graph showed significant group difference.

Fig. 1. Centipede plot of group difference: means and 95% confidence interval of each sexual attraction group on study variables. Note. The mid-point indicates the mean and the bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. In each panel, any two groups with non-overlapping bars were significantly different on the measured variable.

Table 1. Means and s.d.s of study variables by sexual attraction

Note. at, attraction; undevelop, underdeveloped.

A series of multinomial logistic regressions were conducted to test whether being a sexual minority was associated with a greater risk of being bullied and a higher or lower likelihood of bullying others. The birth-assigned sex and sexual attraction category was used as the predictor, and the YES/NO answers to the being bullied or to bullying others were used as dependent variables (the opposite-sex-attraction-girls were treated as the reference group). Details of the ORs and effect sizes are summarised in Table 2; but two trends could be observed: (1) sexual minority groups reported heightened risks of being bullied and bullying others at school than heterosexual girls. However, being a sexual-undeveloped girl seemed to have a protective effect on bullying-related problems; and (2) birth-assigned males were more likely to be involved in being bullied as well as bullying others at school than birth-assigned females.

Table 2. Multinomial regression results indicating associations between sexual attraction and being bullied or bullying others

Bolded value <0.05, significant level was set at <0.05.

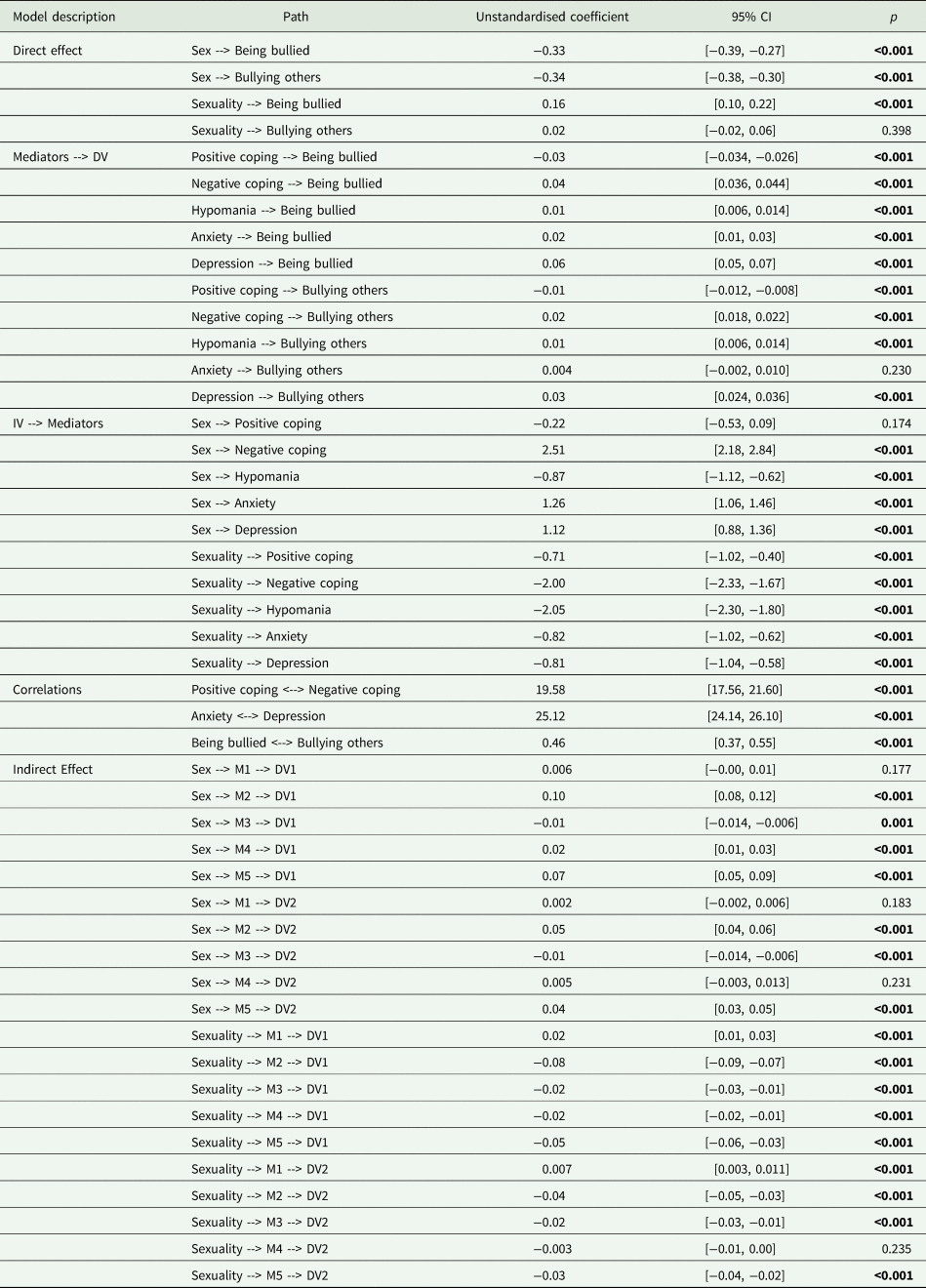

An SEM (Fig. 2) was constructed to examine the mechanism behind the association between sex and sexual attraction and the frequency of being bullied and bullying behaviours, with positive and negative coping, hypomania, anxiety as well as depression as mediators. The results are summarised in Table 3. SEM analysis revealed that being a heterosexual girl was associated with a reduced risk of being bullied and bullying others in comparison to being a heterosexual boy. On the other hand, being a sexual minority was associated with a heightened risk of being bullied. Negative coping, hypomania, anxiety and depression were associated with a higher frequency of being bullied; while positive coping had a significant protective effect on the frequency of being bullied. Negative coping, hypomania and depression were associated with a higher frequency of bullying others, whereas positive coping was associated with a lower frequency of bullying others. Moreover, positive coping and negative coping were positively correlated, and so were anxiety and depression, as well as bullying others and being bullied.

Fig. 2. Final SEM model with the standardized coefficients labelled for each path. Note. ***p < 0.001. Sex: 0 = boys; 1 = girls. Sexuality: 0 = opposite-sex attraction; 1 = all other sexual preference.

Table 3. Summary of the SEM model

Note. Sex: 0 = boys; 1 = girls. Sexuality: 0 = opposite-sex attraction; 1 = all other sexual minority groups. M1 = positive coping; M2 = negative coping; M3 = hypomania; M4 = anxiety; M5 = depression. DV1 = being bullied; DV2 = bullying other.

Bolded value <0.05, significant level was set at <0.05.

In addition, heterosexual girls reported a similar level of using positive coping, a higher level of using negative coping, a lower score on hypomania, a higher score on anxiety and depression in comparison to heterosexual boys. On the other hand, the sexual minority group reported lower usage of positive coping, higher usage of negative coping, a lower score on hypomania, anxiety and depression in comparison to opposite-sex attraction group.

Discussion

This is the first study examining the psychological mechanism behind the pattern of being bullied and bullying others in relation to one's birth-assigned sex and sexual attraction. This study provides insights into how being bullied and bullying others are associated, increases knowledge about related factors of the victim-bully cycle, identifies the importance of coping strategies and mood states, and explores the dynamic nature of being bullying and bullying others in school settings.

Specific socio-demographic features

The current study was composed of 2.2% same-sex-attraction girls, 1.7% same-sex-attraction boys, 7.6% both-sex-attraction-girls and 5.3% both-sex-attraction-boys out of the total sample. According to recent Chinese adolescent research, 4.1% of adolescents self-report as sexual minorities and 17.3% are unsure (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Li, Guo, Gao, Xu, Huang, Deng and Lu2018). Huang et al.'s study covered four regional areas of China, including less economically developed areas. This study was conducted in Suzhou, one of the well-developed economical cities of China. Due to the higher tolerance and friendly environment, adolescents in this study may have been more likely to disclose their sexual minority status rather than report as unsure.

The current research also shed light on a new phenomenon that has not been discussed in previous studies: there could be a number of adolescents who may not have experienced a romantic relationship or have reached a mature sexuality. In previous research, adolescents who reported being sexually attracted to neither male nor female were usually treated as asexual in their sexuality; and the number of adolescents who reported being sexually attracted to neither male nor female is usually quite small (Fenaughty et al., Reference Fenaughty, Lucassen, Clark and Denny2019). However, in this current study, 2625 boys and 2395 girls reported being sexually attracted to neither male nor female. Accordingly, new categories of sexuality were added (sexually-undeveloped boys and girls). The results showed that this subgroup of adolescents seem to be ‘protected’ from the heightened risk of being bullied or bullying others; and they also seem to report better mental health, such as lower hypomania, lower anxiety and lower depression. This may be a culturally specific phenomenon in China since Chinese parents and schools openly discourage adolescent children to be involved in romantic relationships (Li et al., Reference Li, Connolly, Jiang, Pepler and Craig2010). Those adolescents who obey these suggestions tend to have a closer relationship with their parents (Li et al., Reference Li, Connolly, Jiang, Pepler and Craig2010) and receive more positive feedback from school teachers. Consequently, those factors may lead to better mental health and fewer bully-related problems.

Mood problems and bullying

It is well-documented that a sexual minority orientation is a risk factor for bullying and stressful life events (King et al., Reference King, McKeown, Warner, Ramsay, Johnson, Cort, Wright, Blizard and Davidson2003; Berlan et al., Reference Berlan, Corliss, Field, Goodman and Austin2010). Previous studies have shown that compared with heterosexual counterparts, sexual minority participants experience a significantly higher rate of bullying victimisation, with 31–33.9% being bullied v. 18–19.3%, respectively (Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Smith, McDermott, Haro, Stickley and Koyanagi2019; Qi et al., Reference Qi, Palmier-Claus, Simpson, Varese and Bentall2020). In the current results, the prevalence of bullying among sexual minorities was much lower than previous studies. It is possible that participants may feel embarrassed about bullying experiences and the lower prevalence could partly be due to underreporting. Importantly, our results confirmed our hypothesis that being bullied and bullying others are significantly correlated. In addition, a previous study indicated bully-victims may experience the greatest internal distress (Swearer et al., Reference Swearer, Song, Cary, Eagle and Mickelson2001). It is therefore critical that research and interventions continue to primarily focus on individuals who are being bullied and participate in the bullying others.

There is a lack of research on the association between bullying and hypomania in sexual minority individuals. A previous study in a Dutch school setting showed that both bullying and being bullied were associated with an increased risk of subclinical psychotic experiences (Horrevorts et al., Reference Horrevorts, Monshouwer, Wigman and Vollebergh2014). Sexual minorities have an elevated risk of psychosis, which could be due to the experiences of social adversity such as bullying (Qi et al., Reference Qi, Palmier-Claus, Simpson, Varese and Bentall2020) and this association between psychological health and bullying is well-documented (Kaltiala-Heino et al., Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Rimpelä, Rantanen and Rimpelä2000; Bond et al., Reference Bond, Carlin, Thomas, Rubin and Patton2001; Fekkes et al., Reference Fekkes, Pijpers, Fredriks, Vogels and Verloove-Vanhorick2006; Arseneault et al., Reference Arseneault, Bowes and Shakoor2010). Our results showed that individuals with mood problems had a higher risk of being involved in bullying. Individuals with mood problems could face discriminations towards their mental health problems, which makes them more likely to be bullied. Meanwhile, individuals with mood problems have less control over their mood status, which could make them more likely to be involved in aggressive behaviours such as bullying others.

Coping strategies and bullying

This study showed that positive coping had a significant protective effect on being bullied and a preventive effect on bullying others; negative coping was positively associated with being bullied and bullying others. In order to reduce the victim-bully cycle, it is important to coach adolescents to adopt positive coping strategies. Importantly, researchers have noted that sexual minority and heterosexual samples use different coping strategies. For example, gay men preferred to use emotional-oriented coping strategies while heterosexual men preferred to use problem-oriented coping strategies (Sandfort et al., Reference Sandfort, Bakker, Schellevis and Vanwesenbeeck2009), with a lack of current research to understand different types of coping skills based on sexual orientation. Emotional-oriented coping strategies are associated with poorer mental health outcomes, and problem-oriented coping strategies were associated with better mental health outcomes (Sandfort et al., Reference Sandfort, Bakker, Schellevis and Vanwesenbeeck2009). It would be useful for future research to explore the association between sexual orientation (i.e. sexual minority v. heterosexual) and their preferred coping strategies and bullying related information in Chinese adolescents in order to create tailored interventions for each subgroup. Furthermore, it is meaningful to design distinct forms of coping strategies between LGB groups, since sexual minority subgroups might have different needs.

Practical implications

School-age bullying experienced by sexual orientation minorities tends to result in long-term consequences for their overall health and well-being. Recent research in England found that school-age bullying of sexual minority people is positively associated with victims' lower educational level and workplace bullying, while negatively associated with job satisfaction (Drydakis, Reference Drydakis2019). Policies merely aimed at reducing bullying may not be effective, and additional policies are needed to promote safe and supportive school environments (Robinson and Espelage, Reference Robinson and Espelage2012). According to a previous meta-analysis of longitudinal research, school victimisation was positively associated with students' psychological distress (Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010). Many studies have emphasised the benefits of warmth, support and care for sexual minority youth (Shilo and Savaya, Reference Shilo and Savaya2012; Hsieh, Reference Hsieh2014; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Grossman and Russell2019). This study highlighted the importance of providing a supportive school environment to reduce bullying.

Although social support could promote positive psychosocial adjustment for sexual minority youth, the sources of social support for sexual minority youth are sparse (Button et al., Reference Button, O'Connell and Gealt2012; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Grossman and Russell2019). It is important to provide social support to sexual minority youth from parents, clinicians, teachers and classmates (Watson et al., Reference Watson, Grossman and Russell2019). It is essential to provide supportive learning environments for sexual minorities, such as training teachers and staff in sexuality diversity and discussing homophobia in education (Robinson and Espelage, Reference Robinson and Espelage2012; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Espelage and Rivers2013; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Hu, Peng, Xin, Yang, Drescher and Chen2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Hu, Peng, Rechdan, Yang, Wu, Xin, Lin, Duan and Zhu2020). In addition, in terms of school counselling, it is inappropriate to narrowly defined victims and bullies as two separate groups (Ma, Reference Ma2001); the results from this study instead indicate that victims and bullies can belong to the same categories.

Limitations

There are several limitations in the current study. First, we were unable to confirm the causality direction of the measured aspects. Second, the data are from an economically developed region of China, which may not be generalisable to all school settings in Chinese regions. Third, many other variables could affect the victim-bully cycle. Besides sexual minority personal variables, it is also critical to consider variables such as effect on school climate, discipline climate, parental and teacher involvement, academic press and school size (Ma, Reference Ma2001). Future studies should aim to measure those relevant variables and establish a more comprehensive framework of the victim-bully cycle for LGB adolescents.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this research is pioneering in exploring the interaction of being bullied and bullying others among sexual minority adolescents. We investigated the relationship between sexual orientation, mood problems, coping strategies and the victim-bully cycle. It has expanded the understanding of the possible mechanism of bullying others and being bullied among sexual minority adolescents in school settings. Unlike previous studies which investigated sexual minorities as a whole group, we identified the subgroup differences among LGB adolescents, which provided in-depth details for sexual minority adolescents. The current research highlights the importance of providing a supportive and safe learning environment for sexual minority students.

Data

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Author contributions

Study design: WY, YH, YY, CR; Data collection: LR, YY, WS; Data analysis: WY, YH, YY, CR; Data interpretation: WY, YH, YY, CR, DJ, AW; Manuscript preparing: WY, YH, YY, CR, DJ, YY, AW.

Financial support

The study was supported by the Young Medical Talent of Jiangsu Province (QNRC2016229), Suzhou Municipal Sci-Tech Bureau Program (SS2019009), Suzhou Key Diagnosis and Treatment Program (LCZX201616) and Suzhou Clinical Medicine Expert Team (szyjtd201715). The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Suzhou Guangji Hospital, Suzhou University.