Impact statement

This paper expands the reader’s understanding of the lasting impact of COVID-19 on the mental health, particularly depression, of older adults in Korea. Using a longitudinal approach and growth mixture model, it uncovers longitudinal patterns of depression, categorizing them into ‘steadily increasing’ and ‘rapidly rising’ types. Examining demographic factors, including gender, income, education and living arrangements, few specific vulnerabilities of depression among older adults were found. Women, individuals with lower socioeconomic status, and individuals living alone or in urban areas were identified as high-risk groups for particular depressive patterns; the ‘rapidly rising’ type. This study is expected to significantly enhance the understanding of mental health attribution among older adults, providing insights for research and tailored health policies to support the mental health of older adults in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Introduction

The world is currently living in an era of COVID-19. World Health Organization (WHO) declared coronavirus disease (COVID-19) a pandemic in March 2020, and Korea upgraded the crisis alert level to the highest level and strengthened its response system (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). Strong social distancing, movement restrictions and voluntary isolation were implemented as effective measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in many countries, including Korea (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Heesterbeek, Klinkenberg and Hollingsworth2020; Wilder-Smith and Freedman, Reference Wilder-Smith and Freedman2020). In Korea, quarantine policies were implemented considering the stage of disease infection. Based on social distancing, such as minimizing contact with others, individuals were encouraged to limit going out, gatherings, eating out, hosting events, traveling and use of multiuse spaces. Depending on the region, the government strengthened quarantine management, such as administrative orders prohibiting gatherings at certain facilities, suspension of operation of public facilities, refraining from operating multiuse facilities and restrictions on going out, accommodations and in-person visits in facilities that are vulnerable to infection (Ha et al., Reference Ha, Lee, Choi and Park2023).

It is significant, however, that the implementation of strong quarantine measures at the national level had an impact on both the individual and societal levels (Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Shen, Zhao, Wang, Xie and Xu2020). As the epidemic spread, society lost daily lives, experienced a depressive atmosphere and became socially disconnected as well. According to a study comparing anxiety and depression levels prior to and post-COVID-19 in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development member countries and 204 countries worldwide, depression levels increased significantly after COVID-19 (OECD, 2021; Santomauro et al., Reference Santomauro, Mantilla Herrera, Shadid, Zheng, Ashbaugh, Pigott, Abbafati, Adolph, Amlag, Aravkin, Bang-Jensen, Bertolacci, Bloom, Castellano, Castro, Chakrabarti, Chattopadhyay, Cogen, Collins, Dai, Dangel, Dapper, Deen, Erickson, Ewald, Flaxman, Frostad, Fullman, Giles, Giref, Guo, He, Helak, Hulland, Idrisov, Lindstrom, Linebarger, Lotufo, Lozano, Magistro, Malta, Månsson, Marinho, Mokdad, Monasta, Naik, Nomura, O’Halloran, Ostroff, Pasovic, Penberthy, Reiner, Reinke, Ribeiro, Sholokhov, Sorensen, Varavikova, Vo, Walcott, Watson, Wiysonge, Zigler, Hay, Vos, Murray, Whiteford and Ferrari2021).

There is a high likelihood that this phenomenon will exacerbate social isolation among the socially disadvantaged, especially the aging population, who frequently interact outside the home and depend heavily on public services (Armitage and Nellums, Reference Armitage and Nellums2020). Some studies have shown that the psychological risk of COVID-19 is lower in the aging population than in the younger generation due to the resilience (García-Portilla et al., Reference García-Portilla, de la Fuente Tomás, Bobes-Bascarán, Jiménez Treviño, Zurrón Madera, Suárez Álvarez, Menéndez Miranda, García Álvarez, Sáiz Martínez and Bobes2021; Santomauro et al., Reference Santomauro, Mantilla Herrera, Shadid, Zheng, Ashbaugh, Pigott, Abbafati, Adolph, Amlag, Aravkin, Bang-Jensen, Bertolacci, Bloom, Castellano, Castro, Chakrabarti, Chattopadhyay, Cogen, Collins, Dai, Dangel, Dapper, Deen, Erickson, Ewald, Flaxman, Frostad, Fullman, Giles, Giref, Guo, He, Helak, Hulland, Idrisov, Lindstrom, Linebarger, Lotufo, Lozano, Magistro, Malta, Månsson, Marinho, Mokdad, Monasta, Naik, Nomura, O’Halloran, Ostroff, Pasovic, Penberthy, Reiner, Reinke, Ribeiro, Sholokhov, Sorensen, Varavikova, Vo, Walcott, Watson, Wiysonge, Zigler, Hay, Vos, Murray, Whiteford and Ferrari2021). However, it is undeniable that refraining from going out, regardless of their will, during or after COVID-19, the aging population has also experienced depression, stuffiness, loneliness and helplessness to a greater extent than before COVID-19 (Lee and Kang, Reference Lee and Kang2020; Atzendorf and Gruber, Reference Atzendorf and Gruber2021; Krendl and Perry, Reference Krendl and Perry2021; Mishra et al., Reference Mishra, Park, York, Kunik, Wung, Naik and Najafi2021; Seong et al., Reference Seong, Kim and Moon2021). In light of the negative effects of changes (Santini et al., Reference Santini, Jose, York Cornwell, Koyanagi, Nielsen, Hinrichsen, Meilstrup, Madsen and Koushede2020; Atzendorf and Gruber, Reference Atzendorf and Gruber2021) such as social isolation brought about by COVID-19 on older adults, and mental health issues such as depression on their quality of life (Sivertsen et al., Reference Sivertsen, Bjørkløf, Engedal, Selbæk and Helvik2015), and the adverse effects of COVID-19 on their mortality (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Hawkley, Waite and Cacioppo2012) and suicide rates (Waern et al., Reference Waern, Rubenowitz and Wilhelmson2003), it is highly essential to focus on the older population and examine the impact of COVID-19 on them.

The effects of COVID-19 on depression among older adults have previously been studied in exploratory settings, using qualitative methods (Lee and Kang, Reference Lee and Kang2020; Krendl and Perry, Reference Krendl and Perry2021), or in cross-sectional settings after COVID-19 (Robb et al., Reference Robb, De Jager, Ahmadi-Abhari, Giannakopoulou, Udeh-Momoh, McKeand, Price, Car, Majeed and Ward2020; Atzendorf and Gruber, Reference Atzendorf and Gruber2021; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Duan, Shang, Hu, Baker, Lin, He and Wang2021; Seong et al., Reference Seong, Kim and Moon2021), or a short interval before and after the onset of COVID-19 (within 1 year) (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Elgueta, Fernández, Giacoman, Leal, Marshall, Rubio and Bustamante2021; Mishra et al., Reference Mishra, Park, York, Kunik, Wung, Naik and Najafi2021). Consequently, this study aims to complement the previous studies conducted within a short period of time by examining the long-term trends in depression levels of the older adults through a longitudinal study that includes the period following the onset of COVID-19. As the impact of the pandemic may vary by individual (Saunders et al., Reference Saunders, Buckman, Fonagy and Fancourt2021), this study seeks to derive the type of change in longitudinal depression through a growth mixture model (GMM) that can be tracked by considering heterogeneity within the population rather than focusing on average changes or trajectories.

Moreover, this paper will provide a discussion on the influence of demographic characteristics, which have been reported to have an impact on the level of depression due to COVID-19 and which have been major factors influencing the depression of the older adults (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Fonseca, Ferreira, Weidner, Morgado, Lopes, Moritz, Jelinek, Schneider and Pinho2023). To be more specific, based on the findings of Liang et al. (Reference Liang, Duan, Shang, Hu, Baker, Lin, He and Wang2021), who studied older people living in Hubei, China during the COVID-19 pandemic, persons who are not married, have low educational attainment, and have low household incomes report higher levels of depression (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Duan, Shang, Hu, Baker, Lin, He and Wang2021). According to a study of 60-year-old retirees in 25 countries as well as Israel, living alone significantly increases feelings of loneliness and depression (Atzendorf and Gruber, Reference Atzendorf and Gruber2021). In another study, women who reported being single, widowed, divorced, or living alone were more likely to experience depression and anxiety the younger they were, according to a study of older adults (average age 70.7 years) in London, United Kingdom (Robb et al., Reference Robb, De Jager, Ahmadi-Abhari, Giannakopoulou, Udeh-Momoh, McKeand, Price, Car, Majeed and Ward2020). Specifically, in a study aimed at the general public, it was reported that women suffer from higher levels of anxiety and depression after the COVID-19 epidemic than men (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Hope, Ford, Hatch, Hotopf, John, Kontopantelis, Webb, Wessely and McManus2020; Sønderskov et al., Reference Sønderskov, Dinesen, Santini and Østergaard2020; Santomauro et al., Reference Santomauro, Mantilla Herrera, Shadid, Zheng, Ashbaugh, Pigott, Abbafati, Adolph, Amlag, Aravkin, Bang-Jensen, Bertolacci, Bloom, Castellano, Castro, Chakrabarti, Chattopadhyay, Cogen, Collins, Dai, Dangel, Dapper, Deen, Erickson, Ewald, Flaxman, Frostad, Fullman, Giles, Giref, Guo, He, Helak, Hulland, Idrisov, Lindstrom, Linebarger, Lotufo, Lozano, Magistro, Malta, Månsson, Marinho, Mokdad, Monasta, Naik, Nomura, O’Halloran, Ostroff, Pasovic, Penberthy, Reiner, Reinke, Ribeiro, Sholokhov, Sorensen, Varavikova, Vo, Walcott, Watson, Wiysonge, Zigler, Hay, Vos, Murray, Whiteford and Ferrari2021). Additionally, McElroy-Heltzel et al. (Reference McElroy-Heltzel, Shannonhouse, Davis, Lemke, Mize, Aten, Fullen, Hook, Van Tongeren and Davis2022) found that pandemic-induced resource loss affects low-income or vulnerable aging population with chronic diseases (McElroy-Heltzel et al., Reference McElroy-Heltzel, Shannonhouse, Davis, Lemke, Mize, Aten, Fullen, Hook, Van Tongeren and Davis2022). Individuals with disabilities may experience much more vulnerability to mental health problems due to the triple jeopardy of increased risk due to the disease itself, reduced access to routine medical care and rehabilitation and negative social impacts of pandemic mitigation efforts (Shakespeare et al., Reference Shakespeare, Ndagire and Seketi2021). In light of this, this study examined the factors affecting the depressive changes of the older adults before and after COVID-19, with particular emphasis on gender, age, income, education, residential area, living alone and disability based on previous studies.

The goals of this study are as follows: first, to identify longitudinally the types of depressive changes in the older adults before and after COVID-19, and second, delve into the factors that determine the type of change in depression among older adults.

Method

Data

The study was conducted between 2017 and 2021 using the 12th through 16th Korea Welfare Panel Study (KoWePS). KoWePS is a representative panel survey on Korean welfare, aimed at providing policy feedback regarding the implementation of new policies and improving institutions by analyzing the living conditions and welfare needs of various population groups and evaluating the effectiveness of the policy implementation. A total of 12,790 individuals responded to the 12th Korea Welfare Panel Survey, while the 16th survey received responses from 11,278 individuals due to relocation or death. Among them, approximately 30% of the survey participants were older adults. The Korean Welfare Panel Survey utilized a sampling method that considered age, allowing it to be considered representative of various age groups. For this study, changes in depression among individuals aged 65 years or older were estimated from 2017 (12th survey) to 2021 (16th survey), with a final analysis conducted on 2,716 individuals who had no missing values in major variables. Further information on the Korean Welfare Panel Survey can be obtained from the following website: https://www.koweps.re.kr:442/eng/main.do

Variables

Independent variable: Demographic and sociological characteristics

Demographic and sociological characteristics included gender (male = 0, female = 1); age (continuous variable); equalized annual income (continuous variable); education background (under elementary school = 1, elementary school = 2, middle school = 3, high school = 4, university and above = 5); residential area (urban = 0, suburban and rural = 1); living alone (living together with someone = 0, living alone = 1) and disability (having no disability = 0, having disability = 1). Specifically, equalized annual income is calculated by dividing household annual income by the square root of the number of household members, and the logarithm is transformed into a normal distribution.

Dependent variable: Depression

Kohout et al. (Reference Kohout, Berkman, Evans and Cornoni-Huntley1993) developed the abbreviated version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CESD) scale to measure the level of depressive symptoms in a nondiagnostic way (Kohout et al., Reference Kohout, Berkman, Evans and Cornoni-Huntley1993). This study used an abbreviated CES-D developed by Radloff (Reference Radloff1977) and shortened to 11 items by Kohout et al. (Reference Kohout, Berkman, Evans and Cornoni-Huntley1993). Finally, this study utilized the CESD-11 (Korean version of the 11-item CESD) instrument developed by Chon (Reference Chon2001). A 4-point scale is used to measure depression (1 = very rare, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often 4 = the most of the time). The subquestions numbered 2 (indicating how well one was doing) and 7 (assessing whether one lived without major complaints) were reverse coded. The average depression score was then calculated and utilized based on these calculations. As the score is higher, depression is considered to be of higher severity. In this study, the reliability of the depression scale (Cronbach’s α) was. 888 in 2017,. 875 in 2018,. 873 in 2019,. 859 in 2020 and. 879 in 2021.

Statistical analysis

In this study, SPSS version 27.0 and M-plus 8.0 were used for data analysis, and the analysis method and procedure are as follows: First, a descriptive statistical analysis was conducted to identify the demographic characteristics and characteristics of the major variables of the analysis. Second, in order to confirm the type of change in depression among older adults, GMM was conducted. Third, in the mixed growth model, the optimal number of change types was determined through the p values of Akaike’s information criteria (AIC; Akaike, Reference Akaike1987, Bayesian information criteria (BIC; Schwarz, Reference Schwarz1978, sample-size adjusted BIC (SSABIC; Sclove, Reference Sclove1987, entropy (Jedidi et al., Reference Jedidi, Ramaswamy and DeSarbo1993) and bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT; McLachlan and Peel, Reference McLachlan and Peel2000. AIC, BIC and SSABIC values are better correlated with smaller indices. This study attempted to select a model with the smallest AIC, BIC and SSABIC values. A higher entropy indicates the clarity of a latent group classification, and a higher entropy indicates a more accurate classification. The BLRT method is used to select a better model based on the likelihood ratio of both the k-1 group model and the k-group model. A statistically significant value of BLRT rejects the null hypothesis that the k-1 group is more appropriate than the k group. In the fourth step, a binary logistic regression was conducted to determine the factors that determine the type of change in depression among older adults.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The demographic characteristics of the older adults are shown in Table 1. There were 970 men (35.7%) and 1,746 women (64.3%), which is about twice the number of men. The average age of the participants was 71.91 years (SD = 4.77), and the equalized research income was USD $12,574.91 (SD = 9,176.26). A total of 587 (21.6%) were uneducated, 1,196 (44.0%) were elementary school graduates, 432 (15.9%) were middle school graduates, 350 (12.9%) were high school graduates and 151 (5.6%) were university graduates or higher. Over half of the participants accounted for educational attainment below the elementary school level. There were 957 participants living in urban areas (35.2%), and less than 1,759 people (64.8%) living in suburban and rural areas. The number of people who lived with someone was 1,773 (65.3%), which was double the number of people who lived alone (34.7%).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants (n = 2,716)

Note: M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

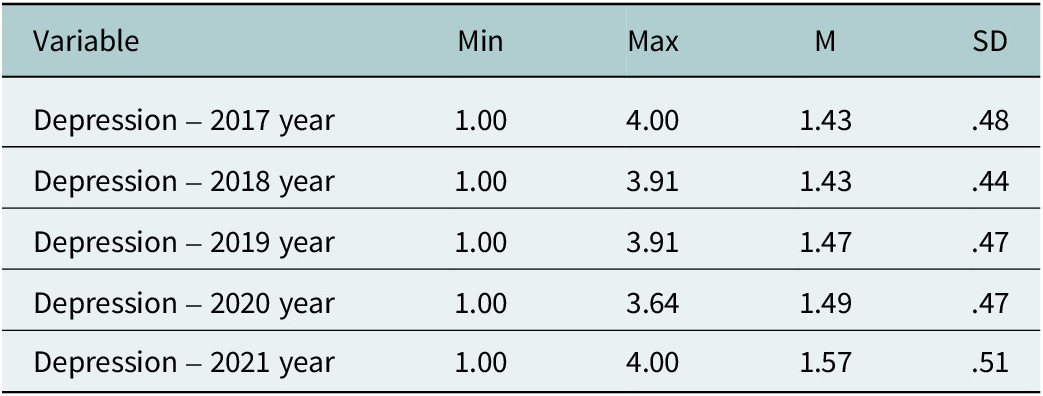

According to a descriptive statistical analysis of depression, the average depression score of the older adults increased from 1.43 points in 2017 (SD = .48) to 1.57 points in 2021 (SD = .51), indicating a gradual rise over time (Table 2). As a result of conducting a paired-sample t test on older adult depression in 2017 and 2021, there was a statistically significant difference (t = −12.535, p < .001). In other words, it was found that depression in older adults in 2021 was significantly higher than depression in 2017. Particularly in 2020 and 2021, as the Korea COVID-19 outbreak began to gather momentum, depression among older adults increased significantly.

Table 2. Descriptive analysis on depression (N = 2,716)

Types of depression changes among older adults

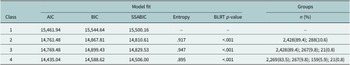

A GMM was conducted to identify patterns of change in depression among older adults. The indicators used to find the optimal type are the p values of AIC, BIC, SSABIC, entropy and BLRT. AIC, BIC and SSABIC of class 4 fitted each model less well than the classes 1, 2 and 3. The entropy of class 3 was closer to 1 than for the other classes. As a result, class 2 was selected for the final analysis as classes 3 and 4 contain a group that composes less than 1% of the total cases (Table 3).

Table 3. Model fir of growth mixture modeling (N = 2,716)

Depression changes in older adults were classified into two types, and the names of each type were determined by the characteristics of the pattern of change (Figure 1). The first type was analyzed as having an initial value of 1.325 (p < .001), a linear change rate of. 046 (p < .001) and a quadratic change rate of. 001 (p > .05). Since depression gradually increased from 2017 to 2021, it was referred to as a ‘steadily increasing’ type. Then, 2,428 participants (89.4%) were classified as this type. The second type was analyzed as having an initial value of 1.787 (p < .001), a linear change rate of. 794 (p < .001) and a quadratic change rate of. 106 (p < .001). Depression stagnated from 2017 to 2019 and then increased significantly from 2020, thus being classified as a ‘rapidly rising’ type, with 288 participants (10.6%).

Figure 1. Estimation of Depression Change Types among Older adults

Determinants of depression change types among older adults

An analysis of binary logistic regression was performed in this paper in order to determine the factors that determine the type of depressive change in older adults (Table 4). The dependent variable in this analysis was the type of change in depression, with 0 set to a ‘steadily increasing’ and 1 set to a ‘rapidly rising’. There were significant determinants of depression type (Coefficient; Coef. = .368, p < .05), equalized annual income (Coef. = − .937, p < .001), educational background (Coef. = − .170, p < .05), residential area (Coef. = − .565, p < .001) and living alone (Coef. = .346, p < .05). In other words, women were more likely to belong to the ‘rapidly rising’ type rather than a ‘steadily increasing’ type, if they live in a large city compared to a small or medium city, or live alone compared than living with someone or have the lower their equalized annual income. To be specific, the odds ratio for gender was found to be 1.445, and it was shown that for women compared to men, the odds of belonging to the ‘rapidly rising’ type increased by 44.5% rather than the ‘steadily increasing’ type. The odds ratio of equalized annual income was found to be. 392 and it was found that when equalized annual income increases by 1%, the odds of belonging to the ‘rapidly rising’ type decrease by 60.8% rather than the ‘steadily increasing’ type. The odds ratio of educational attainment was found to be. 844, and it was confirmed that when educational attainment increases by one grade, the odds of belonging to the ‘rapidly rising’ type decrease by 15.6% rather than the ‘steadily increasing’ type. The odds ratio of the residential area was found to be. 568, and it was confirmed that among participants who live in small- and medium-sized cities compared to large cities, the odds of belonging to the ‘rapidly rising’ type rather than the ‘steadily increasing’ type decreased by 43.2%. The odds ratio for living alone was found to be 1.414, and it was confirmed that the odds of belonging to the ‘rapidly rising’ type’ rather than the ‘steadily increasing’ type increased by 41.4% among participants living alone compared to living with someone. Conversely, neither age nor disability significantly determined depression type changes.

Table 4. Binary logistic regression model of types of change in depression (N = 2,716)

*<.05, **<.01, ***<.001

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the negative effects of COVID-19 among older adults, including social isolation and mental health issues. The purpose of this study is to identify and analyze the types and determinants of depressive changes among older adults before and after COVID-19.

Using a GMM to examine the patterns of change in depression among older adults, COVID-19 tends to make older adults more depressed the longer it continues. Notably, in 2020–2021, there was a substantial increase in depression among older adults. A phased social distancing policy was implemented in March of the following year (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2020) following the first death from COVID-19 in Korea in February 2020 (KCDC regular briefing, February 21, 2020). The correlation between the rise in depression and time can be seen to be significant.

The fact that depression is a significant risk factor for older adults, even without taking into account the COVID-19 situation, is not surprising (Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Beekman, Dewey, Hooijer, Jordan, Lawlor, Lobo, Magnusson, Mann and Meller1999), and increase in age is associated with reduced income, physical disability, diseases and exacerbating depression symptoms (Rodda et al., Reference Rodda, Walker and Carter2011). A similar pattern of depression was found in the older adults in this study. A study of the types of changes in depression among the older adults identified two types of changes: the ‘rapidly rising’ type and the ‘steadily increasing’. The ‘steadily increasing type’, which accounts for 89.4%, showed the association between older adults and depression. In addition, 10.6% of the older adults showed depressive patterns that were similar to the ‘rapidly rising’ type after the COVID-19. The two types of depression met the expectation that depression would gradually increase as social distancing policies were strengthened as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak in 2019.

An analysis was conducted to determine which determinants were associated with the type of change in depression among older adults. These determinants included gender, equalized annual income, educational background, residential area and whether the individual lived alone. In the case of women compared to men, the lower the equalized annual income, the lower the educational level, if the residential area is a large city compared to a small- or medium-sized city, and if living alone compared to individuals living with someone, the probability of belonging to the ‘rapidly rising type’ rather than the ‘steadily increasing type’ increased. Based on the findings in previous studies (Vink et al., Reference Vink, Aartsen and Schoevers2008; Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Wetherell and Gatz2009; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Park and Park2021; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Fonseca, Ferreira, Weidner, Morgado, Lopes, Moritz, Jelinek, Schneider and Pinho2023), it can be concluded that mental health vulnerability factors affecting older adults had a significant negative impact on depression among older adults during COVID-19. It can be inferred that the older adults who reside in large cities where restrictions of COVID-19 are applied relatively intensively, the limitations of convenient urban infrastructures may have led the older adults to experience more severe restrictions than individuals in smaller and medium-sized cities, leading to an increased rate of depression among older adults.

The results were consistent with previous studies in which women experience higher levels of depression due to the cessation of their health and social services as a result of the COVID-19 (Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Shen, Zhao, Wang, Xie and Xu2020). A previous study also indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic is more deadly among groups with lower educational attainment and equalized annual income due to socioeconomic consequences such as income uncertainty and social isolation (Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Lipsitz, Nasri, Lui, Gill, Phan, Chen-Li, Iacobucci, Ho and Majeed2020). Furthermore, the type of change in depression among older people was influenced by a person’s residential area. As a result of outbreak phases concentrated in urban areas, differences in the intensity of local health measures, and fears about infecting large numbers of people during periods of rapid growth in COVID-19 cases, deaths and stigma, older adults living in urban areas were at a higher risk of depression (Mazza et al., Reference Mazza, Ricci, Biondi, Colasanti, Ferracuti, Napoli and Roma2020).

A new daily life has emerged as a result of social distancing implemented worldwide in the era of COVID-19, such as a non-face-to-face format and emphasis on other family members’ care and support. Families are known to be powerful coping mechanisms for depression in older adults (DuPertuis et al., Reference DuPertuis, Aldwin and Bossé2001); however, as the COVID-19 spreads, older people living alone are at a greater risk of experiencing an increase in depression. The lower the equalized annual income, women than men, the lower their education, living in urban compared to rural areas, and living alone compared to living with someone, showed higher likelihood of belonging to the ‘rapidly rising’ type instead of the ‘steadily increasing’ type. This suggests that those at risk of depression are at much higher risk during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The findings of this study suggest that in the event of a pandemic, high-risk individuals who are vulnerable to depression should be identified and social support interventions should be made as early as possible. Indeed, during the COVID-19 situation in 2021, the Watch-type CarePredict Tempo was developed in the United States to allow older people to check their health status and daily life patterns on their own and to provide information to family members and caregivers (CarePredict, 2022). In this regard, it could be regarded as one of the services that facilitate the transmission and preemptive handling of the situation.

Similar services have been implemented in Korea as well. In 2021–2022, 180 older Koreans were provided with AI companion robots from 15 general welfare centers for the older adults in Seoul as AI companion robots gradually spread throughout this field.

As a result of this project, depression levels among older adults were reduced from 10.3 points before the project to 7.4 points afterward, resulting a positive outcome (Community Chest of Korea & Korea Association of Senior Welfare Center in Seoul, 2021). In an emergency such as COVID-19, in which strict regulations (self-quarantines, social distance etc.) are inevitably necessary, new approaches to prevent depression in older people who are at high risk of health, should be intensively and actively reviewed.

It is also necessary to provide timely and effective guidelines to prevent depression in older adults when implementing policies in response to an outbreak of infectious diseases. To achieve this, vaccinations for herd immunity and control of the transmission rate of infectious diseases are two of the most efficient methods. In addition to reducing the likelihood of infection with COVID-19, vaccination against COVID-19 can improve an individual’s quality of life (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Fan, Ahorsu, Lin, Weng and Griffiths2022). It is also important to support leisure activities in order to prevent depression among older adults. Leisure activities can reduce psychological stress and increase enjoyment and vitality in older adults (Marufkhani et al., Reference Marufkhani, Mohammadi, Mirzadeh, Allen and Motalebi2021); therefore, measures such as improving accessibility to leisure activities and developing various programs will be necessary.

Limitations

This study has the meaning of analyzing the increase in depression among older adults in the depression risk group and identifying the determinants of the type of depression change. However, we still have a few limitations. The data used in this study is the largest panel in Korea; however, since the Korea Welfare Panel Survey is data with a high proportion of low-income groups, and there may be a bias in stratification according to demographic characteristics. In addition, due to the limitations of using secondary data, this study was not able to consider physical aspects of older adults, such as physical resilience, as control variables, despite the fact that they can serve as important factors in the development of depression. It is recommended that studies on depression in older adults be conducted in the future with an appropriate distribution of population groups such as age and income.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2023.90.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at https://www.koweps.re.kr:442/eng/main.do.

Author contribution

Kyu-Hyoung Jeong and Ju Hyun Ryu proposed the research question. Kyu-Hyoung Jeong led the statistical analyses. Ju Hyun Ryu, Seoyoon Lee and Sunghee Kim evaluated the data and contextualized the findings. Kyu-Hyoung Jeong and Ju Hyun Ryu prepared the manuscript and drafted the publication. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Ethics statement

All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This report was exempted from approval by the institutional review boards (IRB) of the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Semyung University (IRB number: SMU-EX-2022-06-001). Every participant gave a written consent prior to their participation in the study.

Comments

Cover Letter

26 September 2023

Dear Dr. Gary Belkin, the Editor-in-Chief

Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health

We would like the editors to consider our research article entitled “A Study on the Types of Changes in Depression and COVID-19 among Older Adults in Korea” by Kyu-Hyoung Jeong, Ju Hyun Ryu, Seoyoon Lee, and Sunghee Kim for publication in the Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health.

We would appreciate your consideration of this manuscript for publication in the Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health as an original article. Neither this manuscript nor any portion of it has been published, nor is this work currently under consideration for publication by any other journal. The co-authors have read the manuscript and have approved of its submission to the Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health.

Thank you for your consideration. I look forward to hearing from you.

Yours sincerely,

Ju Hyun Ryu

Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Social Welfare Policy, Yonsei University, 50 Yonsei-ro, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul, 03722, Republic of Korea