A Introduction

The Czech composer Antonín Dvořák served as Director of the National Conservatory of Music in America from 1892 to 1895 and lived in the United States for most of that time. During this productive period Dvořák composed some of his most enduring works, including the Symphony No. 9, the ‘New World’. There has been considerable interest in the extent to which Dvořák's American surroundings influenced his compositions at the time, as well as how Dvořák's compositions in turn influenced the subsequent development of American classical music.Footnote 1

The String Quartet in F major (op. 96), the ‘American’, is central to considerations of Dvořák's compositions from this period. The history of the composition of the American quartet is well established.Footnote 2 Dvořák lived and worked in New York at the time, but he wanted to escape from the city for the summer of 1893. At the urging of his private secretary Josef Kovařík, Dvořák spent the summer in the Czech settlement of Spillville, Iowa, USA. Kovařík had grown up in Spillville and his extended family still lived there, so arrangements were easily made for Dvořák's visit. Dvořák and his family arrived in Spillville on 5 June 1893. Starting on his first full day in Spillville, Dvořák followed a daily routine of early morning walks in nearby woods. During these walks, he was happy to hear birdsong againFootnote 3 after his long stay in New York, and he was often seen sketching out fragments of song for later use.

The composition of the American quartet began on 8 June, just three days after Dvořák's arrival in Spillville, and the entire work was sketched out by 10 June. Dvořák completed the full score by 23 June 1893. It is widely asserted that Dvořák heard the song of a scarlet tanager (Piranga olivacea) during his morning walks in Spillville and incorporated that song into the third movement (Scherzo) of the American quartet. Unequivocal statements to this effect can be found in numerous sources, including scholarlyFootnote 4 and creative writing,Footnote 5 radio and television broadcasts,Footnote 6 concert programme notes,Footnote 7 and at least one musical composition.Footnote 8

Despite the frequent assertion that the scarlet tanager inspired Dvořák's composition of the American quartet, the musical connection between the birdsong and the Scherzo has not been easy to identify. As we will discuss, the scarlet tanager's song is not clearly identifiable in the thematic material of the Scherzo. In 2016, Ted Floyd proposed that the birdsong that inspired Dvořák was in fact a red-eyed vireo (Vireo olivaceus).Footnote 9 If correct, this new identification would necessitate reconsideration of the role of birdsong in this iconic work. Our goals are to 1) trace the history of identification of the bird that inspired the American quartet, 2) evaluate the evidence for different species identification proposals, and 3) reconsider how Dvořák used birdsong as thematic material in the Scherzo. We significantly expand the evidence to support Floyd's new identification and conclude that the song of the red-eyed vireo permeates the Scherzo far more completely than previously understood.

B Eyewitness accounts from Spillville

The primary source for the use of birdsong in the quartet is a letter from Dvořák's secretary Josef Kovařík in correspondence with Dvořák biographer Otakar Šourek in 1927. Kovařík describes the first time the string quartet was played through, with Dvořák playing the first violin.

The following day we played again, we started with the first movement. Maybe it went somewhat better; we started the ‘Scherzo’ – that went much worse – and suddenly, as soon as the first violin climbed to higher positions, the maestro stopped, spat and exclaimed: ‘Faugh! You [damned]Footnote 10 bird!’ We all looked at the maestro in surprise, wondering what had actually happened, but in the meantime the maestro calmed down and said: ‘But it's not the poor bird's fault that I forgot how to play in higher positions!’ And as he later explained, the very first morning of his walks in the forest he came upon a bird, which he watchedFootnote 11 for a whole hour. It was all red, with black wings, and it kept singing (see Fig. 1).

We played the quartet every day, until we finally played it ‘passably well’ – which made the maestro indescribably happy.Footnote 12

Fig. 1 Facsimile of the complete fragment of music in the letter from Kovařík to Šourek in 1927, presumably in Kovařík's hand. Reproduced with permission from Nová and Vejvodová, Three Years with the Maestro, 64. The original document is in the collection of the Museum of Music of the Czech National Museum, Prague

Three separate points can be taken from Kovařík's account:

1) Elements of local birdsong were used by Dvořák in the Scherzo.

2) Dvořák heard the song from a bird that was red with black wings.

3) The four-bar fragment sent to Šourek by Kovařík is a transcript of the source birdsong before it was modified by Dvořák in composition.

It is not widely acknowledged that there was a second eyewitness from Spillville who also described Dvořák's use of a birdsong in the Scherzo. Josef's father, Jan Josef Kovařík (1850–1939), played the second violin during the rehearsal. Jan Kovařík was interviewed in 1933 when he was 83 and living in New Prague, Minnesota.

Dvořák was a very plain man and a great lover of nature. During this visit at Spillville a morning walk through the groves and along the banks of the river was on his daily program and he particularly enjoyed the warbling of the birds, in fact he admitted that the first day he was out for a walk an odd-looking bird, red plumaged, only the wings black, attracted his attention and its warbling inspired the theme of the third movement of his string quartet.Footnote 13

This second account supports points 1) and 2) above. It is difficult to know if these represent independent memories by father and son, or whether they discussed the famous incident together after the fact. Interestingly the elder Kovařík states more directly that the bird inspired ‘the theme’ of the Scherzo, which is only implied by Josef Kovařík.

C History of identification of Dvořák's bird

In 1954, more than 60 years after the composition of the American quartet, British biographer John Clapham was the first to propose that the bird mentioned in Kovařík's account was a scarlet tanager.

The description of the bird immediately suggests the scarlet tanager, which W. E. Ricker of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada informs me is found in N.E. Iowa, where Dvořák was at the time. If this is the bird which he heard then he failed to notice that its tail is black. The writer has been further helped by Eric Simms of the BBC, who kindly allowed him to hear records of American bird songs, and who has said that although the scarlet tanager is a bird of the tree tops, he has seen one take up a position from which it sang within easy sight from the ground. The bird song is very rapid, has shorter rests than in Dvořák's sketch and consists of five, not four fragments; but Dvořák's first unit of two notes occurs during its course, although not at the outset. It is quite possible that the song undergoes some variation. The American robin has a slower but rather similar song, but here no fragments correspond with Dvořák's sketch. The robin has very little red about it. The Virginian cardinal, although similar in colouring to the description of Dvořák's bird, is entirely ruled out because of the nature of its notes.Footnote 14

Clapham apparently had no first-hand experience with American birds, so he depended on help from others. He clearly realized that the scarlet tanager song does not fit the Kovařík fragment in multiple ways. But after eliminating other possible choices based on appearance, Clapham concludes that the scarlet tanager is the most likely choice despite the poor match of its song.

In subsequent publications, Clapham expresses increasing confidence in his identification even though no new analysis was done. In his 1966 book, Clapham remains slightly cautious about species identification and repeats previous statements about the difficulties with the song.Footnote 15 But by 1979, the equivocation was gone and Clapham states simply: ‘The bird was a scarlet tanager’ without mentioning the poor song match.Footnote 16 Though some subsequent commentators express caution about Clapham's identification,Footnote 17 serious doubt is rarely expressed until Floyd rejects the tanager in 2016:

This tanager's song neither looks (spectrographically) nor sounds (aurally) like the bird in Dvořák's American Quartet.Footnote 18

Floyd does not consider the visual description that was the basis for Clapham's identification. We examine Floyd's evidence for song identification in more detail below.

D Evaluation of differing bird identifications

Because there is contradictory evidence from the bird's appearance and the song recorded in the Kovařík fragment, we will evaluate the appearance and song separately.

Appearance

To consider all possibilities for a predominantly red bird with black wings, we systematically examined the appearance of every bird currently found in IowaFootnote 19 by consulting field guides and online images. The northern cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) is a bright red bird with black markings (though not on the wings). Clapham dismisses cardinals based on song. But more importantly, cardinals were almost certainly not present in northern Iowa in 1893.Footnote 20 The range of cardinals expanded northward starting in the nineteenth century, and only arrived in the vicinity of Spillville in the 1910s.Footnote 21

Only two other Iowa birds conceivably could be described as red with black wings: the red crossbill (Loxia curvirostra) and the white-winged crossbill (Loxia leucoptera), though as the name implies the wings of this species have white markings in addition to black. However, these birds are winter migrants to Iowa, and would not have been present in June when Dvořák was listening to birds.Footnote 22

Since the scarlet tanager was the only red bird with black wings found in Iowa in June in the nineteenth century, we conclude that it is the single bird that fits Dvořák's description as remembered by both Josef and Jan Kovařík.

Song

As stated by Clapham in his initial identification in 1954, the Kovařík fragment does not fit either the phrasing or rhythm of the scarlet tanager's song.Footnote 23 Floyd also concludes that the Kovařík fragment was unlike the song of the scarlet tanager, based on examination of spectral sonograms as well as extensive experience with birds in the field.Footnote 24 One musical transcription of the scarlet tanager song is found in Example 1.Footnote 25

Ex. 1 Scarlet tanager song from Judy Pelikan, The Music of Wild Birds (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 2004): 105. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books, all rights reserved

The song is often described as robin-like, but with a distinct burry quality (indicated by the wavy lines in the transcript). These general characteristics are supported by extensive analysis of modern recordings.Footnote 26 Scarlet tanager songs typically consist of four to seven elementsFootnote 27 of one to three notes each. The gaps between the elements are typically shorter than the length of the sung portions,Footnote 28 giving the song a ‘hurried quality’.Footnote 29 In contrast, the song in the Kovařík fragment consists of alternating two- and three-note elements, with an extended pause between them. The two full rests that separate each element in Kovařík's fragment create gaps that are twice the length of the sung portions.Footnote 30 The rhythmic structure in the Kovařík fragment is distinctive and particularly revealing, since both Dvořák and Kovařík surely would pay close attention to rhythm.

We agree with Floyd's conclusion that the differences between the Kovařík fragment and the scarlet tanager song are too great to be a tenable match, especially rhythmically.Footnote 31 The Kovařík fragment is not similar to any tanager song that we personally have heard from live birdsFootnote 32 or in recordings. Similarly, the Scherzo itself lacks any particular passage that has clear connections to scarlet tanager songs,Footnote 33 despite sometimes creative efforts to make it so.Footnote 34

Floyd proposes that the Kovařík fragment is likely to be a transcription of red-eyed vireo song.Footnote 35 We arrived at the same conclusion independently based on our own experience with Midwestern birdsongs. An example of a musical transcription of a red-eyed vireo song is found in Example 2. Note the succession of varying two- and three-note elements (with occasional fours), separated by long rests. Most bars have gaps three times the length of the sung notes so that only 25 per cent of the time in a singing bout is occupied by song. These long gaps are a distinctive feature of red-eyed vireo song,Footnote 36 which is often described as ‘broken’ or ‘interrupted’.Footnote 37

Ex. 2 Red-eyed vireo song from Judy Pelikan, The Music of Wild Birds (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 2004): 111. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books, all rights reserved

The general pattern seen in this transcription is confirmed by thorough study of recorded songs of red-eyed vireos by multiple biologists.Footnote 38 On average, 80 per cent of red-eyed vireo elements consist of two or three notes,Footnote 39 as seen in the Kovařík fragment. On average, red-eyed vireo song bouts consist of 22.6 per cent of time singing and 77.4 per cent in gaps between sung portions. This average gap length is slightly longer than in the Kovařík fragment (with two full rests in each bar, or 67 per cent of time non-singing). However, the observed proportion of gaps ranges from 84.8 per cent to 61.7 per cent among individual birds,Footnote 40 well within the value in the Kovařík fragment.

Although the red-eyed vireo song is distinctive in overall rhythm and phrasing, the song is highly variable both within and among individual birds. Dozens of different specific elements are used by individual birds.Footnote 41 For this reason, the Kovařík fragment would represent only a small fraction of the phrases used by the bird being transcribed. This variation is important to consider when interpreting the use of red-eyed vireo song by Dvořák (see section F, below).

To determine whether there are other birdsongs that fit the Kovařík fragment, we systematically considered the song of every bird known to occur near Spillville during the breeding season.Footnote 42 Specifically, we searched for songs consisting mainly of two- and three-note elements separated by extended pauses. The only other species we identified with these song characteristics was the closely related yellow-throated vireo (Vireo flavifrons). The songs of the two vireos are similar enough that they can be difficult to differentiate in the field (personal observation). However, several characteristics of the yellow-throated vireo song make it a poorer match to the Kovařík fragment. Though there are both two- and three-note elements in the song, most elements are rendered as two notes.Footnote 43 The notes are ‘buzzy’ or ‘burry’,Footnote 44 unlike the clear notes of the red-eyed vireo song. The gaps between elements are even longer than the red-eyed vireo'sFootnote 45 and as a result the ‘tempo is much slower’.Footnote 46 These patterns do not fit the alternating two- and three-part phrases of distinct notes in the Kovařík fragment as well as the red-eyed vireo. We cannot exclude the yellow-throated vireo as a possible source for the Kovařík fragment, but it is less likely than the red-eyed vireo.

E Possible reasons for the mismatched song and visual description

After reviewing all the available evidence, we agree with Floyd's conclusion that the song represented in the Kovařík fragment is most likely that of a red-eyed vireo.Footnote 47 However, the red-eyed vireo could not possibly be described as ‘red with black wings’; adult males have no red or black features, but rather are grey, olive-green and whitish coloured.Footnote 48 The visual description by Dvořák could only be of a scarlet tanager. Some part of the account given in Kovařík's letter must therefore be incorrect.

Assuming that the song fragment and the visual bird description both came indirectly from Dvořák via Kovařík's retelling, how did the mismatch occur? We consider three alternatives.

1) The Kovařík fragment was not the one used in the quartet

There is no direct information about the source of the fragment that Kovařík sent to Šourek 34 years after the Spillville summer. Because Kovařík worked closely with Dvořák and wrote out many of his scores, he must have had full access to Dvořák's notes and papers. The fragment could have come from Dvořák's notes that Kovařík still had in 1927, or he may have copied it from Dvořák's hand into his own notes in 1893 or later.Footnote 49

If Dvořák took notes on a variety of birdsongs on his walks near Spillville, it is possible that Kovařík inadvertently sent Šourek the transcription of a song that was not used in the Scherzo. However, this seems unlikely because of the clear relationship between the Kovařík fragment and motifs in the Scherzo. In 1935, eight years after Kovařík sent his letter with the birdsong fragment, Šourek and his collaborator Paul Stefan were the first to identify bars 21–24 of the Scherzo as the material derived from the Kovařík fragment.Footnote 50 Both the specified bars and the complete Kovařík fragment are reproduced on the page by Šourek and Stefan for direct comparison. Stefan later stated that bars 21–24 are ‘virtually, a rhythmically altered version’ of the Kovařík fragment.Footnote 51

Subsequent analysts have accepted the connection between the Kovařík fragment and bars 21–24 of the Scherzo.Footnote 52 The connection between the Kovařík fragment and the Scherzo seems strong enough to conclude that it is a transcription of the birdsong used by Dvořák.

2) Kovařík misremembered the timing of Dvořák's visual description

A scarlet tanager is one of the most striking birds in the Midwest. Given Dvořák's interest in birds, he surely would have noticed this bird had he encountered it. A sighting would have been all the more memorable because there is no bright red bird to be found among the birds of central Europe.Footnote 53 So it is easy to imagine that Dvořák would have marvelled about an encounter with the beautiful bird to his close acquaintances in Spillville. Years later, Kovařík might have incorrectly remembered that the description of the scarlet tanager occurred at the time of the rehearsal incident.

It is difficult to judge the likelihood that Kovařík made such a mistake. There are some cases where Kovařík's statements of fact have been demonstrably incorrect.Footnote 54 However, Kovařík's father also independently retold the story of a red bird with black wings inspiring the Scherzo. Jan Kovařík could have based his account on later exposure to his son's incorrect retelling of the story. But Jan Kovařík was in fact an eyewitness, so both men would have to have made the same mistake. This is possible, but it seems relatively unlikely.

3) Dvořák mixed them up

A third possibility is that Jan and Joseph Kovařík's memory of the rehearsal incident was correct, but that Dvořák himself mixed up his birds. How might this have occurred? Even though the local birds were unfamiliar to Dvořák, there is no chance that a red-eyed vireo would be mistaken for a scarlet tanager after extended visual observation (‘watched for a whole hour’). However, it is important to reconsider the word previously translated as ‘watched’ in Kovařík's letter to Šourek.Footnote 55 Kovařík used the Czech word ‘sledoval’. This word also can be translated as ‘followed’, ‘pursued’, or ‘tracked’.Footnote 56 Thus it does not necessarily imply visual sighting. Perhaps Dvořák followed a singing bird for an hour, but could not see the bird during most or all of this time.

We suggest that Dvořák encountered both birds on his first morning in Spillville, but heard the red-eyed vireo and saw the scarlet tanager. Both species are currently common during the breeding season in Midwestern forests, including the Spillville area.Footnote 57 Only 14 years after Dvořák's visit, Anderson reported in 1907 that both red-eyed vireos and scarlet tanagers were ‘common summer residents’ throughout Iowa.Footnote 58 Red-eyed vireos generally are among the most common forest birds in their range, and they are well known for singing ‘incessantly’.Footnote 59 Pelikan describes the bird as ‘omnipresent, persistently loquacious, indefatigable, and irrepressible’. Yet despite their abundance and persistent singing, red-eyed vireos are rarely seenFootnote 60 due to their dull colouration and their habit of singing high in the canopy. Tanagers also call from the canopy, but their striking colourFootnote 61 makes them more likely to be seen than the vireos.

One of us (MM) has collected data that illustrate the relative visibility of red-eyed vireos and scarlet tanagers. As a class exercise in an upper-level ecology course at Carleton College, we have regularly censused the birds at Nerstrand Big Woods State Park in Minnesota, 160 km to the northwest of Spillville.Footnote 62 We counted the birds at Nerstrand 25 times from 1990 to 2018, on dates between 21 and 27 May. Red-eyed vireos have been heard every year, with an average of 15.4 birds recorded annually. Yet not one vireo has been seen over the 25 years. Thus we confirm the difficulty of visual observation of the red-eyed vireo, despite its ubiquitous singing. Scarlet tanagers were consistently much less common than red-eyed vireos in our surveys, but they were more likely to be seen when present.Footnote 63

Given these characteristics of the birds involved, it is easy to imagine the events leading to Dvořák's misidentification. He heard the insistent and varied singing of red-eyed vireos in the canopy. He took notes on the song and tried to see what bird was singing. But much as he looked, it would be unlikely that he would have seen red-eyed vireos. Finally, he caught a glimpse of the brightly coloured scarlet tanager, either in the canopy or descended to the understory. Since this was the only bird to be seen, he mistakenly identified it as the one making the calls. Regardless of the details of how the mix-up occurred, we conclude that Dvořák himself was the source of the conflicting visual description and transcribed birdsong.

F Revised analysis of use of birdsong themes in the Scherzo

If a red-eyed vireo inspired Dvořák as he wrote the Scherzo, the well-studied characteristics of this species’ song give further clues about how it was used. We begin with a review of the structure of the movement.Footnote 64

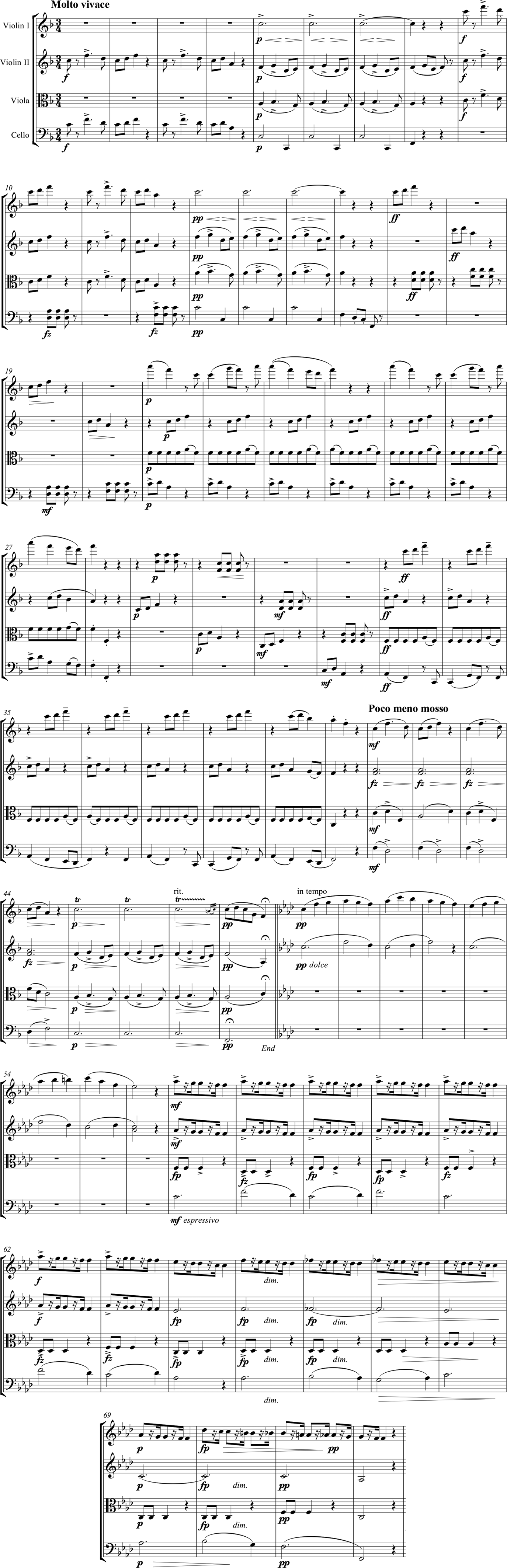

Ex. 3 Antonín Dvořák, String Quartet in F major, op. 96, Scherzo, bars 1–72.

In the Scherzo, Dvořák uses clearly identifiable traditional musical forms and compositional techniques. The movement is a five-part rondo of the form ABABA. The main musical theme appears immediately in bars 1–4, with bars 2 and 4, in particular, repeated and developed as motivic material in much of the remaining A section (through bar 48). For example, the question-and-answer melodic material found in bars 2 and 4 is passed between the first and second violin in 17–20, and then in inverse order in 21–27 between the cello and second violin. The rhythmic gesture of bars 2 and 4 appears in open fifths in the cello in bars 10, 12, 19 and 20, as well as in the viola in bars 17 and 18. Both the melodic and rhythmic components appear consistently in bars 29–40.

A secondary theme appears in bars 21–24, the section long identified with the Kovařík fragment (see section E, above). During the first appearance of the secondary theme in the high register of the first violin, the three-note motifs from the main theme appear simultaneously in the second violin and cello. This secondary theme is repeated in every A section of the rondo, though always accompanied by the main theme as described above.

In the opening of the B section (bars 49–56), the main theme from the A section appears in augmentation in the parallel minor key of F minor in the second violin. This opening version is repeated throughout the B section in all voices except the viola. In bars 57–71, the viola accompaniment uses the rhythmic motif of the A section's main theme. There is some new material in the first violin in bars 49–56. But this new theme is never present without the rhythmically augmented main theme, which appears as the melody in the cello and rhythmically in the viola. The B section notably contains no obvious reference to the secondary theme from the A section.

In summary, the main theme of bars 1–4 pervades the Scherzo, with the secondary theme of the Kovařík fragment used sparingly in the A sections of the rondo. The secondary theme is clearly related to the Kovařík fragment and therefore is strong evidence for Dvořák's use of birdsong. Perhaps it is informative that Jan Kovařík stated that the song of Dvořák's bird ‘inspired the theme of the third movement of his string quartet’.Footnote 65 Could it be that the main theme itself also was inspired by the song of the red-eyed vireo?

Based on the known variation of phrases sung by red-eyes vireos, the Kovařík fragment would have captured only a small fraction of the phrases being sung by an individual bird; individual vireos typically have dozens of different phrases in their repertoire (see note 41). If the main theme came from a different set of elements from Dvořák's bird, we should be able to reconstruct those elements by mimicking the way Dvořák used the birdsong in the Kovařík fragment to construct the secondary theme. The Kovařík fragment and the secondary theme in bars 21–24 are nearly identical, but with two notable changes (see Ex. 4). First, the rhythm has been modified from the birdsong by elimination of the long gaps between motifs; the rhythm of the second motif has also been slightly altered. Second, an extra pickup note has been added to the beginning of the middle two motifs.

Ex. 4 (a) Kovařík fragment compared to (b) Scherzo, bars 21–24, Violin I.

The main theme appears in the second violin in bars 1–4 (Ex. 5). If Dvořák used the same methods to derive the main theme from a different fragment of birdsong, we can reconstruct that fragment as follows. We assume that long gaps would have appeared between motifs, so those can be reinserted. The three-note motifs followed by a rest in bars 2 and 4 presumably represent the three-note elements of a vireo song. Bars 1 and 3 would then be based on the alternating elements of the birdsong. If the birdsong consisted of alternating two- and three-note motifs, then Dvořák must have modified the two-note elements of the song by adding the first or the last note in each bar, just as he did for the Kovařík fragment.

Ex. 5 Scherzo bars 1–4, Violin II.

The rest inserted after the first note in the score suggests that this could be the added note.Footnote 66 Without the extra note and the addition of the typical gaps, the predicted birdsong would then be as in Example 6. This extrapolated song is quite similar to the Kovařík fragment. The two-note motif is the same as that of the Kovařík fragment but lowered by a third; the three-note motif is rhythmically identical to the Kovařík fragment and only slightly different in melody. Alternatively, the first notes of bars 1 and 3 could have been the ones inserted, to give a different two-note motif.Footnote 67 It is also conceivable that Dvořák inserted no notes if the original birdsong consisted of four sequential three-note elements; however, this pattern is less common in red-eyed vireo song.

Ex. 6 Extrapolated song of red-eyed vireo, based on Dvořák's manipulation of the Kovařík fragment to produce the secondary theme of the Scherzo.

All of these possibilities of extrapolated song transcriptions fall well within the range of songs found in red-eyed vireos. In particular the inflections of the three-note motifs have the characteristics of question (rising inflection, bar two) and answer (falling inflection of last note, bar four). The call-and-response phrasing is considered typical of red-eyed vireo song, as described by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology: ‘Each phrase usually ends in either a downslur or an upswing, as if the bird asks a question, then answers it, over and over’.Footnote 68 As a result this reconstructed birdsong is as typical of the red-eyed vireo as is the Kovařík fragment.

We therefore propose that Dvořák based the main theme of the Scherzo on a variation of the red-eyed vireo song that was only slightly different from the Kovařík fragment. Dvořák was well known to have taken copious notes on birdsong, and if he followed a red-eyed vireo for an hour on the morning of 6 June 1893, the ever-varying vireo song would have provided ample material for use in the main theme of the Scherzo. Multiple passages appear to contain the characteristic call-and-response elements of red-eyed vireo songs in different instrumental voices,Footnote 69 just as different individual birds respond to each other when chorusing.

G Conclusion

Based on all available evidence, we conclude that birdsong indeed influenced Dvořák as he composed the Scherzo of the American string quartet. Though the bird has long been identified as a scarlet tanager based on appearance (a red bird with black wings), there is no obvious connection between the song of the scarlet tanager and musical material in the Scherzo. However, the fragment of song recorded by Kovařík is identifiable as a red-eyed vireo, and elements of this fragment are clearly identifiable in the score of the Scherzo. The mismatch between the visual description and the song fragment could have arisen in multiple ways. We suggest that the most likely scenario is that Dvořák was unable to see the incessantly singing but cryptic red-eyed vireo. He then may have glimpsed a strikingly coloured scarlet tanager and misidentified it as the source of the song.

In the ongoing controversy about American influences on Dvořák in this and his other American works, there have been proposals that he utilized musical themes from African American spirituals or from Native American songs.Footnote 70 Such claims have been made since Dvořák's time, and have been controversial from the beginning.Footnote 71 But Dvořák's use of a specific Iowa birdsong in the Scherzo of the string quartet unequivocally shows the direct influence of his American surroundings. It has been suggested that Dvořák used American birdsongs in the New World symphony as well.Footnote 72 Careful examination of Dvořák's other American compositions might reveal other similar connections, or allow rejection of proposed influences.

The conventional structure of the Scherzo demonstrates that Dvořák's creative genius here is manifest in his choice and development of thematic material, rather than in innovative tonalities, musical forms, or compositional techniques. Once he chose a theme for the Scherzo, the use of traditional musical forms likely allowed Dvořák to work remarkably quickly, as demonstrated by the completion of a full sketch of the American quartet in only a few days.

The secondary theme of the Scherzo clearly is related to the birdsong in Kovařík's fragment, as all previous analyses have suggested. But based on the variable nature of red-eyed vireo songs, we propose that the primary theme of the Scherzo was based on an unrecorded fragment of the bird's song. A reconstruction of the missing fragment is typical of red-eyed vireo song and only slightly different from Kovařík's fragment. If indeed both the main and the secondary theme of the Scherzo were based on red-eyed vireo song, then the entire movement can be understood as Dvořák's extended elaboration on the exuberant singing of red-eyed vireos in the Iowa woods in June 1893.