In April 1849, in the southern Brazilian city of Porto Alegre, public prosecutor Antonio Pedro Francisco Pinho filed charges against Manoel Pereira Tavares de Mello e Albuquerque for the crime of reducing to slavery the parda Porfíria and her two sons, Lino and Leopoldino, aged eight and four respectively.Footnote 1 The case, in the form of a “sumário crime” (summary criminal procedure), was based on Article 179 of the Brazilian Criminal Code, which punished with three to nine years of imprisonment and a fine those found guilty of “reducing to slavery a free person who is in possession of his liberty.”Footnote 2 Slavery in Brazil coexisted with a sizable free population of African descent, a result of historically high rates of manumission. After independence from Portugal in 1822, the constitution deemed all free and freed people born in Brazil, regardless of color, Brazilian citizens.Footnote 3 Years later, lawmakers sought to protect free people from enslavement by targeting the practice in the Criminal Code of 1830. As the case of Porfíria and her two sons demonstrates, the enforcement of the measure evoked legal and political challenges.

In many ways, the case of Porfíria and her two sons can be seen as a manumission transaction gone wrong. Some time before the criminal case was filed, the three had been the objects of a transaction between Albuquerque and their former master, Joaquim Álvares de Oliveira. Oliveira had received two enslaved persons in exchange for Porfíria and her sons; Albuquerque apparently wanted to marry the woman to his brick foreman in order to keep him at his job. In her testimony, Porfíria alleged that Oliveira had given her a letter of manumission at the time of the exchange, and this was confirmed by one of the witnesses. The defendant Albuquerque, however, denied this allegation, presenting documents to show that Porfíria’s manumission was conditional on the payment of a certain sum by her future husband. Witnesses for the case were questioned to clarify Porfíria’s status and condition, and she conceded under questioning that she had all along been “under the dominion and captivity” of Albuquerque until she fled for fear of being sold.Footnote 4 In filing a criminal case, the judge deemed her free and a victim of illegal enslavement.

The case of Porfíria was by no means exceptional. In the catalog of nineteenth-century criminal cases related to slavery held in the Public Archives of Rio Grande do Sul, sixty-eight cases relate to accusations of “reducing a free person to slavery” based on Article 179 of the Criminal Code.Footnote 5 The uncertainty of Porfíria’s status was not unique either, and a sizable number of the criminal proceedings as well as many civil actions involved disputes over the status of the person in question. Significant archival documentation exists on the enslavement of free people. And yet, although historians have recently drawn some attention to the subject, it nonetheless remains a neglected topic in the study of Brazilian criminal justice in the nineteenth century.Footnote 6

Some of the most innovative works in the field of Atlantic slavery in recent years focus on the frontiers of enslavement. First, attention was given to geographic frontiers. Since colonial times, even before abolition appeared on the horizon, individuals who sought freedom made use of frontiers; they served native Indians as well as enslaved Africans and their descendants. The benefits of entering foreign territory could compensate for the risky journey, because it was a way to put oneself far from the reach and grip of masters and local authorities. The transit of people through frontiers not only gave rise to a transnational runaway movement but also created, from at least the early eighteenth century forward, an array of diplomatic incidents, given that requests for repatriation were exchanged and limits had to be negotiated.Footnote 7 During the Independence Wars and the movement for slave emancipation in the Americas, however, the transit of slaves through frontiers gained a new status: state formation meant the creation of elaborate legal and diplomatic protocols to guarantee free soil and slave soil. The Brazilian Empire was one of the most powerful American states forged in part to defend slavery.Footnote 8

Besides geographic frontiers, historians have lately turned their attention to the conceptual frontiers of enslavement – that is, to the changes in what was considered legal and legitimate bondage. Studies of legal cases have made it clear that, in different places and in varying circumstances, the illegal enslavement of certain groups was questioned long before the nineteenth-century movement for the abolition of the slave trade and slavery in the Americas.Footnote 9 A closer analysis of freedom lawsuits in Brazil has allowed historians to identify the circumstances that favored or allowed (re)enslavement and to consider the relationship of enslavement to the physical and social vulnerability of its victims, as well as the institutional response to particular cases.

Working within this historiographical framework, with the intention of furthering the discussion about the precariousness of freedom in nineteenth-century Brazil, we will consider here how cases that involved the enslavement of free people were criminalized and brought to court in Brazil throughout the nineteenth century. The cases give an overview of the patterns of enslavement and the varying applications of Article 179 of the Criminal Code. We have divided the cases into three groups, according to the circumstances of enslavement: Africans who were brought illegally after the 1831 ban on the Atlantic trade (along with their descendants); freedpersons who lived in vulnerable conditions; and, lastly, free people of African descent or freedpersons who were kidnapped and/or sold as slaves. Although the number of potential victims of enslavement from illegal trafficking or from ploys of re-enslavement was much greater than the number of people subjected to abductions, these latter cases were brought to justice more often. The most notorious of these were cases involving free people who were physically abducted on the border with Uruguay and sold as slaves in Rio Grande do Sul. Our hypothesis is that the distorted relationship among the number of occurrences, the number of cases filed, and their outcomes points to political choices that influenced the application of Article 179 of the Criminal Code and the law of November 7, 1831, that prohibited the Atlantic slave trade.

The Criminal Code of 1830 and the Crime of Reducing a Free Person to Slavery

The Brazilian Criminal Code of 1830 was seen at the time as an important step toward the modernization of criminal law. Codification was a crucial initiative for a newly independent country that aspired to position itself within the so-called civilized nations. The deputies and senators responsible for drafting the Code took into consideration two bills prepared by José Clemente Pereira and Bernardo Pereira de Vasconcelos, elements of civil codes and statutes from other countries, and debates held in Parliament in 1830.Footnote 10

The bill presented by Deputy Bernardo Pereira de Vasconcelos included an article against the enslavement of the “free man, who is in possession of his freedom,” proposing a sentence of imprisonment with forced labor for a period of five to twenty years.Footnote 11 This was something new, as the Philippine Code, the Portuguese legislation in force in Brazil during the colonial period, did not have a specific provision for the crime of enslaving free people. Indeed, the opposite was the case: legislation at the time allowed for the possibility of holding individuals in captivity if a master wished to revoke manumission granted to former slaves or questioned whether they should live as free people. These cases were regulated by the Philippine Ordinances under the heading “Of Gifts and Manumission That Can Be Revoked Because of Ingratitude,” which applied to freedpersons.Footnote 12 Interestingly, here, re-enslavement was not only legally possible but also based on the premise that enslavement was the natural condition of Africans and their descendants, rendering their freedom always temporary and questionable. All the same, this heading of the Philippine Ordinances applied only to those who had been enslaved, not to just anyone.Footnote 13

Although the Philippine Ordinances sanctioned these instances of re-enslavement, even prior to 1830 there were cases of enslavement of free people that were considered illegal. At least three situations could lead to this: the enslavement of the descendants of Indigenous people (in many cases, the children of Indigenous mothers and Africans or descendants of African fathers), which had been illegal since 1680;Footnote 14 the enslavement of children who were born free, meaning the sons and daughters (who often did not even know they were free) of free women; and disregard for the charters (alvarás) of 1761 and 1773, which prohibited bringing enslaved Africans into the Kingdom of Portugal. Although this last prohibition referred specifically to the Kingdom, there are indications that it was enforced in the African colonies as well.Footnote 15 These three types of offenses led to judicial inquiries. In her analysis of cases of re-enslavement in the cities of Mariana (Minas Gerais, Brazil) and Lisbon from 1720 to 1819, Fernanda Domingos Pinheiro found fifty-four cases that addressed illegal captivity in Mariana alone.Footnote 16 In contrast with the prosecutions against illegal enslavement after 1830, however, these earlier instances were civil cases, not criminal. Although it was possible for someone to contest their illegal enslavement through freedom suits, the practice of enslavement itself was not considered a punishable crime. Thus, before 1830, the only consequence for a slaveholder was the loss of his or her alleged property.

By the time the Criminal Code of the Brazilian Empire was being discussed, the context had changed radically: the lines between slavery and freedom were being redrawn as the country prepared for the abolition of the slave trade. Theoretically, as newly enslaved Africans could no longer be brought into the country, new slaves would come only from natural reproduction. Article 7 in Vasconcelos’ bill was intended to guarantee the freedom of those who were born free, and we cannot assume that it was meant to protect the newly arrived Africans from enslavement.Footnote 17

It is interesting to note that the final version of the article reverses the premise of earlier legislation, which presumed that enslavement was the natural state of Afro-descendants in Brazil. By making it a crime against individual liberty “to reduce to slavery a free person who is in possession of his freedom”Footnote 18 – and thus placing such an action in the same category as undue arrestFootnote 19 – the bill treated enslavement not only as an illegal act but as a violation of the fundamental rights of personhood, which were as inherent in Afro-descendant people as they were in anyone else.

According to Monica Dantas, Vasconcelos probably drew inspiration from the Livingston Code, the Criminal Code proposed in Louisiana in the 1820s.Footnote 20 Indeed, Article 452 of the Louisiana Code states: “If the offense be committed against a free person for the purpose of detaining or disposing of him as a slave, knowing such person to be free, the punishment shall be a fine of not less than five hundred dollars nor more than five thousand dollars, and imprisonment at hard labor, not less than two nor more than four years.”Footnote 21

There is, however, a significant difference in wording between the two Codes. In the proposed Louisiana Code, enslavement was illegal if the perpetrator was aware of the freedom of his victim (which, in a way, always allowed for the defense to claim that the act was based on ignorance of someone’s status), even in cases when the person was living under someone’s dominion. In the Brazilian case, the situation was different. First, it did not matter whether or not the perpetrator had information about the victim’s freedom. Second, enslavement was only criminalized if the victim was living as a free person. The terminology here is particularly important, since it defined the circumstances of the crime and made the assertion of the “possession of freedom” central to legal arguments in lawsuits about enslavement in Brazil. The possession of freedom was the condition that separated illegal from legal enslavement and would serve throughout the nineteenth century to determine whether captives could claim legal protection.

The Prohibition of Trafficking Africans and the Expansion of Illegal Enslavement

The law of November 7, 1831, which aimed to abolish the international slave trade to Brazil, referred to Article 179 of the Criminal Code for prosecution of those accused of trafficking. In other words, legislators chose to charge those involved in the financing, the transportation, and the arrival of Africans, as well as those who purchased newly arrived Africans, with the crime of reducing a free person to slavery.Footnote 22 This interpretation of the law extended the protection afforded by the provisions of Article 179 to newly arrived Africans, whose “possession of freedom” at the time of enslavement was impossible to determine. A decree of April 1832 regulated the procedures, specifying that traffickers should be tried in criminal court, while the status of Africans should be addressed as a civil matter.Footnote 23 This asymmetrical treatment of criminals and victims often led to confusion because the focus on a victim’s status (which, as a general rule, was uncertain) tended to divert attention away from the circumstances of the crime and to minimize the possibilities of punishment.

The law of 1831 became known in Brazil as legislation “para inglês ver” (for the English to see), an expression that, while highlighting British pressure to abolish the slave trade, came to imply in popular usage that the Brazilian government had never intended to apply it. In the last decade, however, research has shown that the uses and meanings of this law varied widely in the nearly sixty years between its adoption in 1831 and the abolition of slavery in 1888.Footnote 24 Despite attempts by the Brazilian government to enforce the law, particularly between 1831 and 1834, the smuggling of enslaved Africans resumed and slowly increased in volume, giving political strength to groups advocating amnesty and impunity for those involved. Between the early 1830s and the passage of the second law abolishing the slave trade in 1850, at least 780,000 Africans were smuggled into the country and held illegally in captivity, a status which was then extended to their children.Footnote 25

Rio Grande do Sul, although not the site of frequent clandestine landings, was nonetheless an area with significant illegal enslavement. Most likely, the labor supply for the charqueadas (dried meat plants), the cattle ranches, and the towns was met through the internal slave trade between provinces. Tracing the actions of the authorities responsible for repressing the illegal trade and the enslavement of free persons in the province brings to light contradictions and variations that existed throughout the country: repression and collusion coexisted with compliance with guidelines from Rio de Janeiro as well as with attempts to challenge those same guidelines in the courts.

A slave landing on the coast of Tramandaí, in Rio Grande do Sul in April 1852, is a good example of varying legal strategies involving “illegal” Africans, strategies in which slaveowners and authorities colluded in order to deflect prosecutorial attempts to enforce the regulations. After having crossed the Atlantic, the ship ran aground in the town of Conceição do Arroio, a district of Santo Antônio da Patrulha, in the province of Rio Grande do Sul. Hundreds of Africans – later estimated between 200 and 500 – were quickly unloaded from the ship. Provincial authorities tried to capture the Africans, but most were claimed by coastal residents, and many were then sent “up the mountains.”Footnote 26 Twenty Africans who were taken into custody by the authorities were emancipated in July and handed over to the Santa Casa de Misericordia in Porto Alegre to fulfill their obligation to provide services as “liberated Africans.”Footnote 27 They had been seized separately, in small groups. Three African boys found in Lombas (a town in the Viamão district) as part of a mission ordered by the vice-president of the province on April 27 were most likely among this group. Authorities rescued the three newly arrived Africans and also arrested Nicolau dos Santos Guterres and José Geraldo de Godoy, who owned the lands where the boys were found.Footnote 28

Historians, long focused on the fate of enslaved people and assuming that the 1831 law was only para inglês ver, have rarely examined the repressive actions of the local authorities or judicial responses to criminal accusations involving illegal enslavement. The cases concerning the Africans who arrived in Tramandaí in 1852 illustrate some of the contradictory measures enacted against such suspects. The two owners of the lands where the three African boys were found, when interrogated by the acting chief of police, claimed that they were unaware of the landing on the Tramandaí coast and that they did not know the people who brought the Africans to the area and offered them for sale. The two did not claim possession or ownership over the Africans, and the authorities did not ask them about how the captives had been acquired. The witnesses who were called to testify could not appear, and the few who spoke about the case said little, simply confirming that the Africans were found on the defendants’ lands. Although the prosecutor characterized the accused men’s actions as a crime against “art. 179 of the Criminal Code, pursuant to the Law of November 7, 1831,” within ten days the interim judge and police chief, Antonio Ladislau de Figueiredo Rocha, dismissed the case for lack of evidence and ordered the two defendants’ release.Footnote 29

Ten years later, the rescue of Manoel Congo, another African man who had landed in Tramandaí, again placed in question the willingness of the Imperial justice system to punish those involved in illegal enslavement. According to Manoel Congo’s account from 1861, someone captured him after the landing, kept him in hiding, and sold him “up the mountains” after a few months. Aware that he was free, he fled from his first master and headed to the Santa Casa of Porto Alegre. But on the way he encountered Captain José Joaquim de Paula, who dissuaded him from going to the authorities, promising him lands in exchange for his labor. Yet a complaint brought against Paula many years later, when Manoel was discovered and rescued from Paula’s property in São Leopoldo, made clear that this promise had been a deception. Not only had been Manoel been baptized as a slave despite one vicar’s refusal to cooperate, but around 1854, in an attempt to forge documents that would legitimize Manoel Congo’s enslavement, Paula had falsified a document attesting that he (Paula) had purchased Manuel from another supposed “owner,” promising Manoel freedom after eight years of labor.Footnote 30 Seized in 1861, Manoel was sent to the Santa Casa de Misericórdia in Porto Alegre where, according to the records, he worked as a “liberated African.” Paula, in turn, was accused of an offense against Articles 167 and 265 of the Criminal Code, which addressed deceit and the use of falsified documentation to exploit a person. In addition to not being accused of the crime of reducing a free person to slavery, Paula was able to appeal his eventual conviction on charges of deceit, which suggests that he may have gone unpunished, despite the fact that the case had garnered significant publicity.Footnote 31

During the preliminary police inquiry, Deputy Gaspar Silveira Martins addressed the Provincial Assembly to criticize the police chief’s handling of the case, specifically alleging that the chief had not ordered the arrest of José Joaquim de Paula or insisted on obtaining evidence to corroborate Paula’s version of the facts. Martins’ fellow assembly members, however, defended the provincial authorities, based largely on their belief in Captain Paula’s good faith. The principle of good faith was used regularly to exculpate those who owned Africans illegally. Silveira Martins responded by proposing to shift the burden of proof from the enslaved to the enslaver: Paula should prove that he had acquired the African legally (by donation, inheritance, exchange, purchase, or other legal means of property transfer) and show that he did not know, and could not have known, that it was an illegal sale: “Paula claims in his defense that he purchased this African from one Agostinho Antonio Leal, and if this is true, he should prove the purchase with a rightful title, and prove further that Agostinho could legally possess this slave.”Footnote 32 Silveira Martins insisted that the document of manumission was falsified, that there was no record of the master having paid the regular sale tax, and that these facts, together with the testimony of the African, should serve as evidence of the crime. He even accused the chief of police of criminal prevarication, insinuating that he was protecting the captain because he was a person of power and a second-tier elector in Brazil’s two-tier electoral system.

Gaspar Silveira Martins had received his law degree from São Paulo in 1856 and had been a municipal judge in Rio de Janeiro since 1859, in addition to being provincial deputy from Rio Grande do Sul. He came from a family of large landowners on the border region with Uruguay, “of the farroupilha liberal tradition,” and in the late 1860s was involved in the Radical Club of Rio de Janeiro, one of the first republican associations in the country.Footnote 33 The young lawyer and deputy, like other radical lawyers and judges, interpreted the 1831 law to mean that Manoel Congo should have been free since landing in Brazil, and therefore Captain José Joaquim de Paula had reduced a free person to slavery. The Ministry of Justice, however, only recognized the right to freedom of Africans rescued at sea or soon after landing on the mainland, thus informally guaranteeing the right to property acquired by smuggling and protecting the holders of illegal slaves from the criminalization of their acts.Footnote 34

A supposed “threat to the public order” was another justification often used to avoid the emancipation of Africans who were being held in illegal captivity. In 1868, other Africans from the 1852 Tramandaí landing turned to Luiz Ferreira Maciel Pinheiro, the public prosecutor of Santo Antônio da Patrulha, to plead for freedom. In Conceição do Arroio, an investigation based on the procedures indicated in the Decree of 1832 was led by the judge, who prepared to “liberate a large number of people from slavery.” The putative owners intervened and instigated a debate about the value of the victims’ testimony. They complained that the Africans in question “had high stakes in the outcome”; therefore, their depositions could not be taken into account. Prosecutor Maciel Pinheiro, in turn, accused “the masters of these and of other Africans” of being criminals who sought to block the actions of the judiciary. But the voice of the putative owners was more powerful than the judicial proceedings, and Pinheiro, under pressure from the provincial president to terminate the case, resigned.Footnote 35 A young graduate from Paraíba who was trained in Recife Law School and had been a colleague of the abolitionist poet Castro Alves, Pinheiro was one of the new voices in the legal field who challenged the policy of collusion in cases of illegal enslavement.

Re-enslavement of Freedpersons

Although it is practically impossible to quantify, there is no doubt that the practice of re-enslaving freedpersons was a frequent occurrence in nineteenth-century Brazil. Several factors contributed to this. First, it was possible until 1871 to legally revert manumission. Although the procedure was complex – the only motive contemplated in the Philippine Code was ingratitude – and the number of cases decreased significantly in the second half of the century, this masters’ prerogative might have enabled other ways of retaining dominion over freedpersons. Secondly, conditional manumission was very common and implied a “legal limbo” that put people’s freedom in peril. Did the freedperson start to enjoy the benefits of freedom at the time of manumission or when certain conditions were filled? This uncertainty was particularly damaging to freedwomen, since it cast doubt on the status of their children. Finally, the precariousness of life in freedom, which forced freedpersons to seek protection from higher-status patrons and made it difficult for them to differentiate themselves from slaves, also facilitated re-enslavement. In general, those victims who managed to get their cases to the courts did so through civil suits, which were denominated ações de liberdade when victims had actually been re-enslaved and ações de manutenção de liberdade when they simply ran the risk of re-enslavement. These cases rarely generated criminal proceedings.

The criminal case involving Porfíria in 1849, with which we began this chapter, stands out, shedding light not only on the mechanisms of re-enslavement but also on how the judicial system addressed these crimes. In suits like Porfíria’s, the central legal question was the definition of “possession of freedom,” and the jurists involved were far from reaching a consensus on the matter.

Manoel Pereira Tavares de Mello e Albuquerque called himself the “master and possessor” of Porfíria and her sons; he sought to demonstrate that she lived under his rule and that she was considered a slave in Porto Alegre, so much so that she had collected alms to pay for her manumission. The procedural discussion and the examination of witnesses revolved around whether Porfíria and her children actually possessed their freedom or not. The police chief, who was also a municipal judge, dismissed the complaint against Albuquerque, having concluded that Porfíria and her children were not in “possession of freedom,” which implied that they were not under the protection of Article 179 of the Criminal Code. Moreover, the chief/judge determined that “the right of the mother and her children is not a given,” meaning that he doubted their status as free persons, which led him to send Porfíria to a civil court so that her status could be determined before the criminal investigation moved forward.

All of this revealed that even the legal definition of possession was complicated at this time. The variety of meanings conferred on the notion extended back to Portuguese medieval law; until at least the middle of the thirteenth century, the words “possession” and “property” were designated by a single expression, iur (from the Latin ius), which shows that they were imprecise and confusable terms. In this context, it was possible for a person to obtain ownership of a thing, be it a farm or a person, after possessing it, even if only for a few years. Over time, the concepts of possession and property came to be dissociated, thus increasing the time it took for a possession to be considered property. Yet, even though the right of ownership of some property was contested, possession was still guaranteed to the possessor in the absence of contrary proof, as jurist Correia Telles emphasized in 1846:

Title XIII: Rights and obligations resulting from possession

The possessor is presumed to be master of the thing until it is proven otherwise. If no one else proves that this thing is his own, the possessor is not required to show the title of his possession. If all have the same rights, it is the possessor who has the best condition of all. Any holder or possessor must be protected by Justice against any violence that is intended to be done.Footnote 36

This last sentence illustrates how difficult it was to deal legally with cases based on Article 179. For example, how were the courts to handle cases of conditional freedom – quasi-possession, in legal terms – which was the liminal status of many freedpersons at that time?

Pinho, the public prosecutor in Porfíria’s case, thus tried to recast the issue when he appealed the decision to the Municipal Court. Doubting the validity of the documents presented by the defendant and insisting on Porfíria’s right to freedom, he directed the legal debate to the moment when manumission took effect. He attached to the records a letter of conditional manumission given to Porfíria and her children by their first master, which had been ignored when they were sold. Pinho claimed that Albuquerque could not “deny them this possession, because freedom is not a material object to be held on to, but rather, it is a right acquired by the person to whom it is transmitted or granted, from the moment in which it is granted.” Pinho thus argued that Porfíria and her children possessed civil liberty even though they did not have the material possession of the manumission letter. He reasoned that freedom was granted in the act of manumission and did not depend on the realization of autonomy or the end of the alleged master’s domain over Porfíria. In the end, the case was decided against Porfíria, since the judge in charge of the case rejected the prosecutor’s appeal.

This question of when a freedperson would be considered legally free occupied multiple jurists and even resulted in a discussion at the Brazilian Bar Institute (Instituto dos Advogados Brasileiros – IAB) in 1857, eight years after Porfíria’s case was first opened. As noted earlier, this was a particularly sensitive issue for women, since their status determined that of their children. In the case discussed at the IAB, manumission had been granted in a will, conditional on the provision of services after the death of the master. Jurist Teixeira de Freitas, then presiding the IAB, defended the minority position, according to which the freedperson would be considered free only after fulfilling the conditions, which implied that the children born in the interval between manumission and the fulfillment of the conditions would be born slaves. By contrast, for jurists Caetano Alberto Soares and Agostinho Marques Perdigão Malheiro, freedom was granted in the will, even though the freedperson would only enter into the full benefits of freedom when conditions were fulfilled. Under this interpretation, which was the official position adopted by the IAB, any children that the freedwomen gave birth to in that interval would be free. This decision preserved the principle of seigneurial will, so dear to defenders of property, while simultaneously opening a space for the interpretation of freedom as a natural right and for manumission as the restitution of freedom, principles that would guide gradual emancipation in Brazil.Footnote 37

Kidnapping and the Enslavement of Free People

The original focus of Article 179 of the 1830 Criminal Code was the enslavement of persons already recognized as free, whose cases would not have raised the same doubts regarding admissibility as did cases involving conditionally manumitted persons or newly arrived Africans. Still, the proceedings reveal the limits to criminalizing the common practice of illegal enslavement, which intensified around 1850 with the closing of the Atlantic slave trade and the rise of the price of slaves.Footnote 38

Although the enslavement of free people has not been systematically investigated, scattered studies give evidence of the profile of the victims, who were most often children or young people of African origin, especially boys, or Afro-descendant women of childbearing age.Footnote 39 In Rio Grande do Sul, the border with Uruguay was decisive: most of the victims were kidnapped from “beyond the border,” an expression used by Silmei de Sant’Ana Petiz to describe escapes to Uruguay and Argentina in the first half of the century.Footnote 40 This geographic detail turned cases of illegal enslavement in the province into diplomatic issues, adding a new layer of complexity to the analysis of how authorities reacted when faced with calls to crack down on these activities.

Although enslaved individuals were being smuggled across borders long before the criminalization of illegal enslavement, the act took on new significance with the independence movements and the gradual abolition of slavery in the former Spanish colonies of South America, which included the enactment of legislation forbidding the slave trade and declaring freedom of the womb. Illegal kidnappings could then be considered, in fact, an expansion of the frontiers of enslavement, much like that identified by Joseph Miller in Angola, in which people were illegally enslaved outside areas where enslavement, even if not always legal, was accepted by local authorities. The profile of the victims – predominantly children – also coincides with Benjamin Lawrance’s characterization of nineteenth-century illegal trafficking in Central and West Africa.Footnote 41

In this context, the border between Uruguay and Brazil constituted a region particularly prone to illegal enslavement. Fully integrated to the agrarian economy of Rio Grande do Sul, it was an area of extensive land holdings and low population density. Most landowners in the north and northeast of Uruguay were Brazilian, and in several of these locations slaves made up one-third of the total population, similar to the figures in Rio Grande do Sul at that time.Footnote 42 Especially in the 1840s, the troubled situation in Uruguay and the political instability of the province of Rio Grande do Sul contributed significantly to the increase in the number of people crossing the borders. The Farroupilha Revolution (1835–1845), the Gaucho separatist movement against the Brazilian Empire, and the Guerra Grande (1839–1851), a civil war between the Blancos and Colorados in Uruguay, provoked significant social unrest in the border region, with military incursions on both sides, cattle and horse theft, and the appropriation of slaves to enlist as troops. The tensions in the border area became even more heightened when, desperate for men for its defensive troops, the Colorado government of Montevideo, of which Brazil was an ally, proclaimed the abolition of slavery in 1842. The Blanco government of Cerrito followed with a proclamation in 1846. Aggravated further in the early 1850s with the end of the Atlantic slave trade to Brazil, these factors contributed to a situation which made the Afro-descendants north of the Negro River easy prey to a new form of human trafficking organized on the border of Brazil and Uruguay that lasted from the mid-1840s until at least the early 1870s.Footnote 43

It is difficult to ascertain how many of the free people who were victims of kidnapping managed to report the crimes. Probably few. At any rate, unlike the cases of newly arrived Africans and re-enslaved freedpersons, evidence suggests that the Imperial authorities began to seriously address the enslavement of persons recognized as free as of 1850. The problem, clearly not contained to Rio Grande do Sul, was raised in the reports of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Indeed, the trafficking of free Uruguayans went all the way to Rio de Janeiro.Footnote 44 The frontiers of enslavement also expanded into the Brazilian interior, and in 1869 the minister of justice monitored three cases of illegal enslavement of free persons: two involving minors in Bahia and Pernambuco, the third involving a family of Africans in Minas Gerais.Footnote 45

At a moment when Brazil was suspected of turning a blind eye to the illegal trafficking of slaves, cases involving other countries were taken even more seriously, as the Brazilian government was concerned about negative international repercussions. The abduction of the minor Faustina, analyzed in detail by Jonatas Caratti, is a good example of this situation. In February 1853, the president of the province of Rio Grande do Sul asked the chief of police of the southern city of Pelotas to investigate the whereabouts of Faustina, who “as a free person, was seized by a Brazilian and sold as a slave in that town.”Footnote 46 A few days later, the Uruguayan authorities demanded the extradition of Faustina, arguing that she was Uruguayan and free. The complaint seems to have had an effect: in an attempt to obtain more information about Faustina, her father, having informed the authorities of her daughter’s abduction, was interrogated in Melo, Uruguay; her baptismal record was also located and sent to Brazil. While this was happening, Loureiro, the judge in charge of the case, expedited the order to arrest Manoel Marques Noronha, accused of the crime, on the “presumption of guilt.” Noronha was found, arrested, and questioned. The judge concluded that he was in fact guilty, finding that the complaints and documents were sufficient evidence to prove the girl’s free status.

Faustina was released and taken home to Uruguay, but the case did not stop there: because of the seriousness of the accusation, the Noronha trial was brought to a jury, made up of the “good citizens” of Pelotas. Noronha defended himself, arguing that he was suffering political persecution. He further alleged good faith, accusing Maria Duarte Nobre, from whom he had bought Faustina, of being the real culprit. The jury accepted the defendant’s arguments and acquitted him, and by September 1854 he was already free from prison. Maria Duarte Nobre was convicted of the crime; however, as she had never been arrested and was not imprisoned during the trial, she remained free. In the end, nobody paid for the crime of Faustina’s enslavement. Her release, however, allowed the Brazilian authorities to demonstrate their commitment to suppressing the illegal slave trade and preventing illegal enslavement. Two years later, Manoel Marques Noronha was again accused of kidnapping; this time the victim was twelve-year-old pardo Firmino. Of the many cases of kidnapping and illegal enslavement of free people on the border of Brazil and Uruguay, Noronha was the only person convicted. He was condemned and sentenced to three years of prison and the payment of a fine, but, as he brought his case to the Court of Appeals in Rio de Janeiro, it is not known whether he actually ever served his prison sentence.

In this same year, the African Rufina and her four children had a fate similar to Faustina’s. Abducted in Tacuarembó, Uruguay in 1854, they were taken to Brazil and sold there. Somehow, Rufina managed to report the crime to the Brazilian police. It became a lawsuit that caught the attention of journalists and the Uruguayan and British consuls in Porto Alegre. At the time, British Foreign Minister Lord Palmerston wrote to Brazil’s minister of foreign affairs, Paulino José Soares de Souza, requesting energetic measures against this “new form of trafficking” taking place on Brazilian borders. Rufina was not only freed but also reunited with her family and returned to Uruguay. None of the kidnappers, however, were convicted. They alleged that they were trying to recover escaped slaves and were unaware of the free or freed status of those kidnapped, and the jury acquitted them all.Footnote 47

The conclusion here is somewhat obvious: because of the diplomatic attention they received, cases of enslavement from “beyond the border” reached the courts more frequently than other cases. In the early 1850s, the Brazilian government was forced to take a stand, and it thus pressed the local courts to prosecute captors who imported slaves into Brazilian territory.Footnote 48 But already in 1868, during the Paraguayan War, when the Brazilian military depended largely on the mobilization of the Gaucho troops, the minister of justice decreased the pressure on slaveowners on the southern border, stating that the alleged owners of anyone brought from Uruguay to Brazil and illegally enslaved should only be prosecuted under Article 179 if they refused to admit the victim’s right to freedom.Footnote 49 Nonetheless, the central government did not support the practices of enslavement by masters on the borders in Rio Grande do Sul in the same way or on the same scale, as it overlooked cases involving the illegal enslavement of freedpeople or turned a blind eye to the large-scale enslavement of newly arrived Africans.

Conclusion

In late 1851 and early 1852, a major popular revolt against a civil registration law erupted in the backlands of Northeast Brazil. The people who protested against the new law had one recurring concern: to protect their freedom, as they understood that the mandatory civil registration was actually a strategy to enslave free people of African descent after the prohibition of the Atlantic slave trade. They probably feared that civil registration would make official the threats of illegal enslavement they observed in their daily lives.Footnote 50 Hardened and cynical from decades of forced military recruitment and severe physical punishment equivalent to that of slaves, they did not trust local authorities to generate vital records or to secure their status.Footnote 51

Although there were no reports of this type of manifestation in southern Brazil, it is plausible that the free population there would have had the same fears. The general picture outlined in this chapter, although preliminary, suggests that the practice of illegal enslavement was recurrent and was met with a variety of legal responses, depending on the victims and the context. Of the 2,341 criminal cases listed in the catalog of crimes related to slavery in Rio Grande do Sul in the years between 1763 and 1888, sixty-eight, or about 3 percent, were related to reducing free persons to slavery.Footnote 52 Thirty-five of those cases refer to illegally enslaved persons, and twenty-nine of those were “beyond the border,” confirming that it was the politically and diplomatically charged cases that were most criminalized. Almost all such cases took place in the 1850s and 1860s. Of the sixty-eight cases, the outcome of five was inconclusive (because of trials records with no final verdict, missing pages, etc.). In twelve cases, the decision called for the release of the enslaved victims. None of the defendants in these cases were punished, even though the determination of freedom constituted, in practice, an acknowledgment of the crime. In forty-eight of the cases, the accusation against the slavers was dismissed or they were acquitted. In only three of the sixty-eight cases were the defendants convicted under Article 179 of the Criminal Code, and in two of those it is not known whether they were actually ever imprisoned. In one case, from 1856, the defendant appealed to the Court of Appeals of Rio de Janeiro, and the final verdict is not known; in the other, which occurred in Encruzilhada do Sul in 1878, the defendants were convicted but then released when the guilty verdict was dismissed. Apparently only Joaquim Fernandez Maia, who was prosecuted for beating and enslaving a nine-year-old, João, was sentenced to prison based on Articles 179 and 201 of the Criminal Code. It is important to note that the three cases that led to convictions referred to free or freed people enslaved by a third party.Footnote 53

The early 1870s brought about changes. It had already long been impossible to legally enslave Africans, and after 1871, with the establishment of Free Womb Law, the enslavement of newborn children was prohibited as well. The law of 1871 also created a mandatory slave registry that, for the first time, would generate a record of who was held in slavery and by whom, definitively closing the borders of enslavement. This mechanism, however, also had the role of legalizing the slave status of those Africans who had been smuggled into Brazil or otherwise illegally enslaved.Footnote 54 It is true that among the stipulations of the Free Womb Law and subsequent decrees was a prohibition on registering as a slave a person who had been conditionally manumitted, which subjected anyone who did so to the penalties provided for in Article 179.Footnote 55 Of the twenty-four cases in Rio Grande do Sul between 1763 and 1888 that involved conditionally freed persons, twelve of them were brought to court precisely in this period, in the 1870s and 1880s. Extending protection to conditionally freed persons implied that they counted, at least for the legislators, as free people in possession of their freedom. However, this was not the understanding that prevailed in the courts. Most commentators of the Criminal Code, when discussing the application of Article 179, indicate that by 1860 the possession of freedom had become a mandatory requirement in cases that would be tried by the jury.Footnote 56 This indicates that the judiciary came to limit the criminalization of illegal enslavement to only those cases where the victim was undeniably free. This approach had important consequences: as they were not viewed as criminal offenses, cases of illegal enslavement would be brought to court as civil suits (ações de liberdade), thus increasing the load on the civil courts. Moreover, the enslavers, even if they lost the slaves, went unpunished.

The existence of court proceedings refutes the conclusion that there was a general collusion between the authorities of the judiciary, legislative, and executive branches – at all levels of power – with illegal enslavement. The cases analyzed here suggest that the prosecutors played an important role in identifying the mechanisms of illegal enslavement and defending the victims. Yet they were overrun by judges who declared the cases inadmissible, by juries that acquitted the defendants, and by superior courts that decided in favor of property even if it was illegally acquired. It is clear that criminals were rarely brought to trial even in the 1880s, when engaged lawyers and judges succeeded in expanding the chances for liberation through freedom lawsuits. In practice, the Brazilian judiciary allowed for the liberation of individuals through civil cases and made it difficult, if not impossible, to pursue any criminal conviction. After all, the liberation of particular individuals through freedom lawsuits had a impact (albeit limited) on the dynamics of nineteenth-century slavery in Brazil, but this would not be true of criminal offenses. If the enslavers were punished for the crime of illegal enslavement, the potential impact would have been much greater and could even have jeopardized the very survival of master–slave relations, especially after the end of the Atlantic slave trade. Faced with this situation, by guaranteeing impunity to the enslavers at each new phase of the relations among slaves, masters, and the Imperial government, the Brazilian judiciary supported a pact that maintained slavery.

Introduction

The transatlantic slave trade to Brazil became illegal after November 1831. Yet as many as a million African slaves came to the country between 1831 and the early 1850s, when the Eusebio de Queiroz Law finally extinguished the trade. Ineffectiveness did not, however, imply impotence: the 1831 ban still had a profound impact on Brazil’s economy, politics, and society. It forced the trade to shift its physical operations from conspicuous ports in the Empire’s principal coastal cities to natural harbors and beaches controlled by provincial landowners, many of whom were also the slave trade’s avid customers. The trade’s new geography and clandestinity spawned important new business opportunities: scores of people were employed in the trade – guiding the slave ships as well as landing, feeding, healing, guarding, and distributing the contraband survivors of the middle passage – and the 1831 law also consolidated the already existing articulation between slave smuggling and cabotage, responsible for a thriving slave trade among Brazil’s coastal areas since colonial times. These new economic networks grew embedded in local and provincial politics; in Brazil, as in Africa, the imperatives of Britain’s high seas antislavery campaign had to be weighed against the complex internal structures that fortified the slave trade. Multitudes of traders, plantation owners, bureaucrats, and small-time slaveowners depended on slavery and did all within their power to prolong it. The continuous contraband of slaves after 1831 was visible enough to all Brazilians, but the trade’s profitability and centrality to national political and economic structures meant that top governmental officials – including members of several Imperial cabinets – were more than willing to favor power over the letter of the law in the two decades between 1831 and the early 1850s.

Needless to say, the people involved in the contraband of African slaves to Brazil tried to hide their participation. Investigating the process is thus difficult: one must face omissions in the sources and ferret out the secrets kept by those who took part in, condoned, and benefited from an illegal business that involved some of the richest and most powerful men in the country. This chapter will uncover some of those secrets by focusing on the illegal slave trade to the province of Pernambuco between 1831 and the 1850s. This focus is significant for two reasons. First, while there is a wide literature about the Atlantic slave trade to Brazil after 1831, we still know little about how it actually operated – its logistical unraveling on Brazil’s remote beaches – or how the adjustments it engendered influenced both the nature of the trade and the evolution of local networks of economic and political power. Second, although Pernambuco’s slave trade was in some ways singular, the province was Brazil’s third and the Americas’ fourth most important destination for enslaved Africans: 854,000, or 8.1 percent of those who came to the Americas between 1501 and 1867, arrived in Pernambuco.Footnote 1 Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, the province lagged only behind Rio de Janeiro, Bahia, and Jamaica. Regardless, and surprisingly, what David Eltis and Daniel Domingues da Silva claimed a decade ago still remains true: the slave trade to Pernambuco is less investigated than those to Cuba, Haiti, and the United States, locations that received far fewer African people.Footnote 2

In the following pages I will discuss how Pernambuco’s slave trade adapted to the new circumstances created by the 1831 ban. Landing sites shifted to beaches adjacent to plantations. British anti–slave trade squadrons noted the growing use of smaller vessels, which were cheaper, faster, easier to hide, less visible to the British navy, and more capable of entering hidden natural harbors and creeks in both Brazil and Africa. The 1831 law also probably spurred a significant rise in the number of adolescents and children forcibly brought to Pernambuco from West Central Africa. As Herbert Klein has observed, children were usually a distinct minority in the trade before the eighteenth century.Footnote 3 This changed in the 1800s. Children were frequently forced onto nineteenth-century slave ships;Footnote 4 despite slave-dealers’ reluctance to trade in them, there was a widespread and significant increase in the importation of people from five to twenty years of age to Brazil between 1810 and 1850.Footnote 5 While Klein and others have argued that this transformation reflected changes on the African supply side, the timing and geography of the change suggest it could also have had much to do with the 1831 law. Briefly put, the ban created new logics for profit within the slave trade, especially valorizing agility and subterfuge. Although the slave trade to Pernambuco was less capitalized than that to Rio de Janeiro and Bahia, the trip’s short duration drastically reduced the human and monetary risk of voyages undertaken in the tiny, overcrowded vessels that could promise clandestinity. Traders could reap abundant profits if they were willing to use small ships, pack them with the compact bodies of children and adolescents, and forge active partnerships with the complicit plantation owners who controlled the coast, roads, and towns around surrounding Brazil’s natural harbors. In encouraging these new and brutal economic logics, the 1831 ban deeply impacted both the social demographics of Pernambucan slavery and the political and economic networks that structured the province.

Camilo’s Story and the Networks of the Clandestine Trade

The 1831 law presented slave traders with abundant challenges, all of which required strong local networks to overcome. Traders had first to find a proper harbor or beach to land their human merchandise; although the Brazilian coast is gigantic, a slave ship could not stop just anywhere. Once an adequate harbor was found, a human network had to be constructed to facilitate clandestine trade on potentially perilous shores. Systems of signs were devised to communicate with slave ships, including bonfires that were lit at nightFootnote 6 to guide incoming ships.Footnote 7 In Pernambuco, fishermen also used jangadas, locally made catamarans, to reach distant slave ships, guide them to the beaches, and help to disembark.Footnote 8 At least one slave ship was captured off Pernambuco at the moment its captain was riding a jangada to the Cabo de Santo Agostinho beach.Footnote 9 Once on land, there was need for security, water, and food. Plantation owners, who controlled local lands, roads, and towns, were essential in providing these goods and guaranteeing that the trade would remain an open secret.

It was at a beach adjacent to a sugar plantation that an African boy, who would later be named Camilo, disembarked, enslaved, sometime after 1831. Camilo believed that he was in his forties in 1874, when he filed a civil suit to gain his freedom before the judge of Itambé, Pernambuco.Footnote 10 He could not state exactly how long he had been in Brazil: twenty-seven to thirty years, he said. Supposing he was right about his age, the Congolese boy probably disembarked in Pernambuco in the early 1840s. He did not remember the name of the vessel; to him, it would have made little difference. Perhaps the boy was too terrified to pay attention, for he was only “nearly seven years of age” when he faced the middle passage. When he first filed his freedom suit with a notary, Camilo said he did not know the name of the beach where he landed. But when he spoke to the judge later the same day, he claimed to have landed at “Itapuí,” probably Atapus, one of the continental beaches surrounding Itamaracá Island near Catuama, an important natural harbor north of Recife frequently used for slave smuggling. He was taken from there – at midnight, he said – to “Major Paulino’s” Itapirema plantation, where he was imprisoned for a few days in the casa de purgar (the building where the plantation’s cane syrup was boiled) along with “ninety” other Africans.Footnote 11 We do not know their ages, but they were certainly his malungos – that is, fellow captives who were brought to Brazil on the same slave ship.Footnote 12

After a few days, Camilo said, he was bought by a man named Rochedo (later identified as Joaquim de Mattos Alcantilado Rochêdo) and taken to the house of the “Portuguese” Manoel Gonsalves in Goiana, then the second most important town in the province (smaller only than Recife in terms of population). The boy walked there with four other captives, who had died by the time Camilo filed his freedom suit. The judge asked if the other slaves had remained at Itapirema´s casa de purgar; Camilo answered that, when he left for Goiana, some others had likewise departed, also in small groups at night, but that half of his fellow captives remained. Once in Goiana, Camilo and his four companions were baptized in the lower room of a sobrado (a large townhouse) belonging to Manoel Gonsalves. According to Camilo, the priest (whose name he could not remember) was white and tall. His godfather was “Agostinho de tal” (de tal meaning that Camilo did not know the man’s last name), whom the clerk described in parentheses as a “natural” son of the sobrado owner. It was at this point in his life that the seven-year-old Congolese child became Camilo: the records did not preserve his African name.

After Camilo and his malungos Abraham, Manoel, Luis, and Justino were baptized, they were returned to Manoel Gonsalves, the owner of the sobrado where the baptism was performed. After a few days’ pause for rest and recovery, Camilo, Luis, and Justino were sent to Perory, a sugar plantation in the same county owned by Manoel Gonsalves’s legitimate son, Major Henrique Lins de Noronha Farias. Abraham and Manoel stayed in Goiana. Camilo thus came to serve a planter family that lived in the same county he had landed in; when the judge asked him where Agostinho, his godfather, lived, Camilo said he also lived at Perory, “Major” Henrique’s plantation. This provides a revealing clue about those plantation owners´ family arrangements; as was relatively common in Brazil at the time, members of the same extended family occupied different social classes according to the nature of their parents’ relationship. Major Henrique, the legitimate son, owned the plantation, whereas Agostinho, the “natural” son, lived there as a dependent of his half-brother. We do not know if they shared the same skin color, but Agostinho was certainly a free man. Camilo survived his first masters only to serve another generation of the same family; after Major Henrique’s death, Camilo told the judge, he was inherited by Belarmino de Noronha Farias, Major Henrique’s son and Manoel Gonsalves’ grandson.

Camilo’s odyssey was repeated by countless African children who were smuggled into Brazil after the 1831 anti–slave trade law. Young people, mostly teenagers but sometimes even children, constituted common cargo on slave ships. That seven-year-old African boy renamed Camilo was one; two others were Maria and Joaquim Congo, who testified in a freedom suit filed by Maria in 1884. Maria and Joaquim were around fifty in 1884, but like Camilo they had been just children when they disembarked in Pernambuco “some forty-something years” earlier, in Joaquim Congo’s words. Joaquim’s recollections were confirmed by Narciso Congo, an older African, aged fifty-six, who worked as a “water carrier” on the streets of Recife. Narciso Congo and Joaquim Congo were witnesses for Maria in her suit; they were also malungos, for they had all arrived on the same ship. Joaquim clearly stated he was no longer a captive at the time he testified and that the claims he had made to be freed could be extended to Maria. He said he was granted freedom “for having proved” that he was illegally smuggled to Brazil after 1831. In 1884, he was a whitewasher (caiador) living in Santo Amaro das Salinas, a parish of Recife that was home to many freedmen and women.

Narciso Congo also stated that he was no longer a captive in 1884, and he too had a story to tell. He said he landed with Maria and Joaquim at the beach of Porto de Galinhas. Unlike Maria, Joaquim, or Camilo, Narciso Congo was around sixteen years of age when he arrived in Brazil. He was soon baptized in the town of Cabo, located at a very traditional plantation area south of Recife, where several plantation oligarchies were based, including that of the Baron of Boa Vista, president of the province of Pernambuco between 1837 and 1844. We do not know any more details about the circumstances of Narciso´s baptism. But soon thereafter he ran away. Narciso did not talk about his escape route in his statement, except to note that he was “caught in Recife.” He was then sent to work at the Arsenal de Marinha, the headquarters of the Brazilian navy in Recife. This is an important detail, because fugitive slaves with known masters were generally sent back to them after capture. The Arsenal, in contrast, was the place “liberated Africans” were taken to and put to work; Narciso’s presence there reinforced his claim of free status.Footnote 13 Narciso stressed the fact that he was brought to Brazil on the same slave ship as Maria and confirmed she was just a “girl” (menina) when she arrived.Footnote 14

Camilo, in his forties in 1874, and Maria and Joaquim, aged fifty in 1884, had been about the same age when they disembarked in Brazil sometime in the 1840s; they might all have arrived around the same time, perhaps even in the same year, when the Baron of Boa Vista was president of Pernambuco. Nevertheless, they definitely came on different voyages, for Camilo landed on one of the beaches near Goiana, north of Recife, while Maria, Joaquim, and Narciso arrived at Porto de Galinhas, south of Recife. They were all baptized in important towns in plantation counties, which proves that the local clergy condoned the illegal slave trade; one witness even identified the “white and tall” priest who baptized Camilo as one “Father Genuíno.” Apart from the teenager Narciso – virtually an adult at age sixteen – the others were just enslaved children who fell from the Congolese slave trade networks into the web of transatlantic smuggling. They should have been freed immediately after reaching Brazilian soil. Or at least that is what the 1831 anti–slave trade law stated. Instead, they were given Portuguese names and remained enslaved.

Children and the Material Calculus of the Middle Passage

Louis François de Tollenare, a French cotton merchant who spent a few months in Recife between 1816 and 1817, witnessed one of those slave ships full of boys and girls docking at the port in 1817. The trade of “Congo” captives (those captured south of the equator) to Portuguese America was then still legal. In Tollenare’s words, only one-tenth of the slaves in the transatlantic slave trade to Pernambuco were full-grown men. No more than two-tenths were young women between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five. The rest of the human cargo, 70 percent, comprised children of both sexes.Footnote 15 Perhaps Tollenare exaggerated when he generalized this particular observation to the transatlantic slave trade as a whole. According to José Francisco de Azevedo Lisboa, a slave trader on the Pernambuco route, a very young cargo was not the most profitable one. In February 1837, Lisboa authoritatively instructed employees at a slave trade feitoria (outpost)Footnote 16 by the Benin River that it was very important to know how to choose among the slaves offered by the African nobility and middlemen under the suzerainty of the king of Benin. Older people, who were rejected at African fairs, should be rejected by the Portuguese as well, unless they were “women with full breasts” (negras de peito cheio). The most valuable merchandise for the “country’s taste” (gosto do país) were young twelve- to twenty-year-olds.Footnote 17 So Narciso, who was sixteen, was more valuable than boys and girls like Camilo, Joaquim, and Maria.

All the same, even if the resale value of children below twelve years of age was lower, they were still good merchandise, and improvements in shipping speeds rendered them a better value still in the nineteenth century. At the pinnacle of the slave trade in the eighteenth century, when the business was still legal, child slaves were assessed lower taxes in the Americas and toddlers were usually exempt. But high mortality rates signaled the frailty of such young human cargo.Footnote 18 By the last quarter of the eighteenth century, however, the slave trade moved on faster voyages and resulted in lower mortality rates. It therefore became easier to transport pre-adolescent children, and in the nineteenth century they would become ubiquitous in the transatlantic slave trade. According to Eltis, the child ratio in slave ships steadily increased after 1810.Footnote 19

Captain Henry James Matson had long experience combating the slave trade when he told the British Parliament that the trip from the African coast to Cuba took as long as three months, whereas the route to Brazil was half as long and much simpler, requiring much smaller crews, which meant that old or low-quality vessels could be used. For this reason, Captain Matson asserted, Brazilian smugglers could afford to lose three or even four out of five slave ships and still make a profit, an equation that was impossible for ships heading for Cuba.Footnote 20 And of all the slave smuggling destinations in Brazil and the Americas, Pernambuco enjoyed the quickest access from West Central Africa, because of the Benguela current and the Atlantic winds. Inferring from Captain Matson’s logic, smugglers could risk overloading slave ships sailing to Pernambuco, because shorter voyages meant reduced time for the spread of diseases in the hold or on deck, as well as fewer deaths from starvation or dehydration. Smaller, more vulnerable children were especially good merchandise if the trip was short.

In 1839, the British consul at Recife wrote that the crossing from the Portuguese possessions in Africa to Pernambuco could take as little as fifteen days, which led smugglers to overload their vessels.Footnote 21 When he described the slave trade to Pernambuco in 1817, Tollenare said the journey from Africa was very fast and that he had heard tell of a vessel that crossed the Atlantic in thirteen days, resulting in a nearly zero mortality rate.Footnote 22 The brief duration of the trip would have made it possible to bring scores of children in the slave ship that Tollenare described.

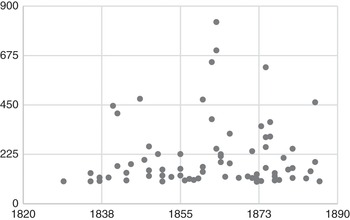

Perhaps the British consul and Tollenare exaggerated. But some voyages were indeed very fast. The schooner brig Maria Gertrudes, listed in Table 2.1, took no more than twenty days to bring 254 live captives from Angola to Recife in 1829. The ship was named after the wife of the slave trader Francisco Antonio de Oliveira, the man who brought the largest number of African slaves to Pernambuco in the 1820s.Footnote 23 Experienced slavers like him were able to cross the Atlantic very quickly. The Jovem Marie took only eighteen days to travel from Cabo Verde islands to Recife, although we do not know if it brought any slaves to the province. In 1831, the brig Oriente Africano and the schooner Novo Despique sailed only nineteen days from Angola to Recife.Footnote 24 The fastest documented trip after 1831 was the 1840 journey of the schooner Formiga, which sailed from Luanda to Recife in just seventeen days.Footnote 25

We do not know how many Africans were aboard the Novo Despique and the Formiga, but the brig Oriente Africano brought fourteen freed Africans and eight captives owned by the captain himself.Footnote 26 The case of the Formiga is intriguing, because – although we have no direct evidence of human cargo – the goods within the ship suggested participation in the illegal trade. The Formiga arrived in Recife from Luanda in 1840, with only three Portuguese passengers. It was consigned to Pinto da Fonseca e Silva, probably a well-known Rio de Janeiro slave dealer who had contacts in Pernambuco.Footnote 27 Apart from its few passengers, the ship carried only palm oil, wax, and mats, which were not nearly valuable enough to justify the trip. This was a very typical cargo for slave ships during the era of the illegal slave trade, when vessels left their more precious human cargo at natural harbors on the coast and proceeded to the major towns of Brazil in order to make repairs and organize subsequent voyages to Africa or elsewhere. The Formiga’s seventeen-day journey suggests that Tollenare and the British consul in Recife may not have been too far from reality when they claimed that a slave ship could arrive in fifteen days or less.

Table 2.1 Slave ships that entered Recife’s harbor, according to the Diário de Pernambuco, 1827–1831.

Similarly, in their study of the slave trade to Pernambuco, Daniel Domingues da Silva and David Eltis estimated that it was possible to arrive there in less than thirty days. On the basis of large samples for Bahia and Rio de Janeiro but data from only three voyages to Pernambuco, Eltis and Richardson concluded that, between 1776 and 1830, a slave ship took on average 40.9 days to reach Rio de Janeiro, thirty-seven days to Bahia, and only 26.7 days to reach Pernambuco.Footnote 28 The sample in Table 2.1, drawn from research in the daily newspaper Diário de Pernambuco between 1827 and 1831, shows almost the same average: 26.1 days from Central-West Africa to Recife, although, as we have just seen, it was occasionally possible to make this trip in less than twenty days.

The Advantages of Illegal Child Trafficking

Such quick voyages to Pernambuco clearly made the trade of captive adolescents and children from Angola and Congo easier: it is thus unsurprising that it became more common in the nineteenth century. The presence of children entered the vocabulary of the slave trade early on. Moleques, mulecões, and mulecotas recur in slave trade-related sources and express common Brazilian understandings of age. Yet it is worth highlighting that these words were not originally Portuguese. According to Joseph Miller, their root derives from muleke, “dependent” in Kimbundu, one of the major languages of West Central Africa.Footnote 29 Assis Júnior translated mulêKe as a “young man, boy, servant.”Footnote 30 In contrast, Valencia Villa and Florentino stated that the expression moleques, in the plural, probably originally referred to children of any sex below twelve years of age.Footnote 31 These possibilities are not necessarily contradictory. Many captive adolescents and children were male dependents, “servants” in West Central Africa, who were frequently sold in different markets before ending up in the web of the Atlantic slave trade. But other categories of captive children were also frequently sold elsewhere in Atlantic Africa, and the word moleque thus gradually lost its conceptual and geographical specificity and came to include young people from the Gulf of Guinea. By 1640, when Portugal separated from Spain, the term had entered the Portuguese language, according to Miller, and it still appears frequently in Brazilian Portuguese.Footnote 32

From the cold-blooded perspective of slave merchants, there were some advantages to buying children. They were relatively defenseless and therefore less able to effectively rebel in the middle passage. They ate and drank less.Footnote 33 They abounded at sales points in West Central Africa in the nineteenth century and were less expensive than adults. In Africa, children were more vulnerable than adults, both to razzias (slave raids) and natural catastrophe; they could also more easily be kidnapped and were subject to tributary systems and debt relations that eventually justified their enslavement.Footnote 34 From the beginning of the slave trade, there were social, economic, and political trapdoors that caught children and threw them into slavery.Footnote 35 It is thus little wonder that Captain James Matson, one of the most iconic characters of the British squadron that patrolled the coast of Africa to combat the Atlantic slave trade, said that 1,033 of the 1,683 captives he seized from slave ships were children.Footnote 36

This was further aggravated by the turn of the nineteenth century because the overwhelming volume of the eighteenth-century slave trade put pressure on the supply side of this most lucrative type of business. West Central Africa was much less populated than West Africa, and adults were better able to defend themselves. Soon, new forms of enslavement emerged, endangering children whose parents, close relatives, or lineages could not effectively protect them. Even in places where there were no wars, razzias, or kidnappings, defenseless children could still be enslaved. Children could be given as security for debts, and Roquinaldo Ferreira and Mariana Candido have observed that West Central African legal tribunals, backed both by Portuguese authorities and by African middlemen and nobility, often ratified the enslavement of dependent people (servants, retainers, and their children), who could easily fall prey to the Atlantic slave trade networks and end up in one of the slave ships bound for the Americas.Footnote 37

After 1831, when the trade to Brazil became illegal, there was yet another advantage to trading captive children. This was revealed in a letter from Augustus Cowper, the British consul in Pernambuco, to the Count of Clarendon on November 3, 1855, regarding the capture of an unnamed pilot boat at the Barra de Serinhaém (about 80 kilometers south of Recife). This episode embarrassed Brazil’s Imperial government, for the ship was seized with enslaved captives aboard five years after the 1850 Eusebio de Queiroz law, which had been passed by the Brazilian government under heavy British pressure in order to put an end to the contraband of African slaves.Footnote 38 After 1850, the Brazilian government tasked its navy and local coastal authorities with ending the trade. However, some ships still evaded detection. One of them was the unnamed pilot-boat that came to Serinhaém in 1855, the last one seized in Brazil with captives inside its hold. The boat was only 30 tons but contained 250 captives when it arrived in Santo Aleixo island, facing the beach of Serinhaém – adjacent to Porto de Galinhas – on October 10, 1855. A vessel’s tonnage measures volume, not weight. In the early nineteenth century, when the transatlantic slave trade was legal, a slave ship was allowed to carry up to five captives per 2 tons, according to Article 1 of the notorious 1813 alvará (decree) that regulated the matter.Footnote 39 The British consul in Recife found it absurd that so many people could fit inside a 30-ton schooner that, according to the tight rules of the 1813 alvará, should have carried only seventy-five slaves. He inferred those captives must have come from some larger vessel far away in the ocean. Indeed, perhaps that was the case; slave traders sometimes used that strategy. But very small slave ships packed with Africans also crossed the ocean toward Pernambuco after 1831. This may very well have been the case here, for the ship was not overloaded with adults. According to the British consul, of the 250 captives thirty were women, and all the rest were just boys. The consul explained that this could have indicated a new strategy that involved bringing only “untattooed boys” to Brazil.Footnote 40 The consul may have used the wrong word, for he probably meant that the boys had no scarifications, the diacritical marks of African populations who were subjected to the Atlantic slave trade. Those boys, in other words, were so young they had not been yet initiated in their original African communities. They did not bear what Brazilians called “nation marks” (marcas de nação) and could thus easily pass as crioulos (Brazilian-born enslaved people, not subject to the 1850 law).

Consul Cowper was probably mistaken when he said that ship was the first one intentionally filled with captives lacking scarifications. Until the Brazilian government decided to fight slave smuggling on the Brazilian mainland in the early 1850s, smugglers were very successful in cheating the British navy and going about their business as usual. That strategy was not new in 1855, for there were children inside slave ships before; kids like Camilo, Maria, or Joaquim were also so young that they were probably unmarked. In this sense Consul Cowper´s account is precious, for it explicitly reveals a critical advantage to bringing children to Brazil after the 1831 anti–slave trade law: they could more easily pass as crioulos (Brazilian-born slaves) and therefore be sold anywhere in the presence of authorities without suspicion.

This case also shows that, as brutal as it was, bringing children on small vessels was quite normal from the slave traders’ perspective. Tiny ships could more easily cheat the British navy, for they were harder to spot. And bringing children as cargo allowed traders to make the most of their limited cargo space. It is even likely that some ships were built with precisely that idea in mind. According to Lieutenant R. N. Forbes – the commander of the Bonetta, one of the British vessels that patrolled the African coast – nothing was done without reason in the slave trade. In his reports, Lieutenant Forbes praised the beauty of some slave ships, but he also stressed their exiguity, expressed especially in cramped corner spaces that were only 14 to 18 inches high, specifically designed to carry children. According to Forbes, some ships were virtually built for that purpose. In his words, the Triumfo (sic), a tiny 18-ton yacht seized in 1842, was one of these “hellish nurseries.” In addition to a crew of only five Spanish seamen, the vessel carried a fourteen-year-old girl and 104 children aged between four and nine.Footnote 41

Lt. Forbes’ reference to “hellish nurseries” suggests that the British consul may have been mistaken in 1855, when he found it somehow absurd that a small 30-ton vessel could carry 250 people, even if 220 were children so young that they had not been initiated in their original communities. Perhaps Consul Cowper simply could not imagine that the small boat in Serinhaém was just one of those hellish nurseries that Lt. Forbes spoke of, crowded with children from West Central Africa.

The slave ship commander Theodore Canot wrote in his memoirs about a similar episode involving a tiny boat with only two sailors and a pilot, which escaped the British navy and fled to Bahia with a cargo of thirty-three boys. According to him, this grotesque yet successful adventure encouraged other smugglers to repeat it.Footnote 42 Pastor Grenfell Hill narrated his journey from Mozambique to Cape Town on a slave ship that carried 447 people, which was seized by the British in 1843; forty-five were women and 189 were men, few more than twenty years old. The rest of the human cargo was composed of 213 boys.Footnote 43 According to Manolo Florentino’s calculations, the hold where those people were piled up was no bigger than 70 square meters (about 750 square feet).Footnote 44 According to Robert Harms, the British had a word for such tight packing of people: “spooning,” for it resembled the stacking of spoons.Footnote 45