Introduction

The general conclusion from studies of multi-episode schizophrenia is that males compared to females appear to be at greater risk of developing schizophrenia and have a more severe form of the illness with regard to onset, symptoms, and psychosocial functional outcome (Abel, Drake, & Goldstein, Reference Abel, Drake and Goldstein2010; Aleman, Kahn, & Selten, Reference Aleman, Kahn and Selten2003). Understandably, researchers have turned to the initial course of schizophrenia to further examine early sources that contribute to sex differences. First episode studies also show that males compared with females have an earlier age of illness onset, lower levels of premorbid adjustment, lower baseline social and role functioning, more negative symptoms, and overall poorer course and outcome (Ochoa, Usall, Cobo, Labad, & Kulkarni, Reference Ochoa, Usall, Cobo, Labad and Kulkarni2012). Researchers are interested in understanding sex differences in social and role functioning in search of ways to better understand prognosis and to improve outcomes.

Studies published thus far have generally not addressed possible mediation pathways that could explain better outcomes observed in females. This process involves examining the literature for possible mediators such as age of onset, premorbid adjustment, neurocognition and social cognition, and negative symptoms that have been found to been associated with outcomes in schizophrenia. Mediation analyses can then examine whether those predictors of outcome are mediator of the relationship between sex and functional outcomes. One study is an example of this approach, finding that females had better verbal memory compared to males and that a sequence of verbal memory and negative symptoms mediated functioning assessed at one year (Buck et al., Reference Buck, Lavigne, Makowski, Joober, Malla and Lepage2020).

Better premorbid functioning in schizophrenia has been associated with a better prognosis, so sex differences in premorbid adjustment might have implications for short and long-term functional outcome (Addington & Addington, Reference Addington and Addington2005; Brill et al., Reference Brill, Levine, Reichenberg, Lubin, Weiser and Rabinowitz2009; Minor et al., Reference Minor, Friedman-Yakoobian, Leung, Meyer, Zimmet, Caplan and Keshavan2015; Stoffelmayr, Dillavou, & Hunter, Reference Stoffelmayr, Dillavou and Hunter1983). One recent study suggested that the more favorable premorbid and baseline functional characteristics of women predicted better outcomes during the first three years of follow-up when treatment was delivered in early intervention services (EIS) (Ayesa-Arriola et al., Reference Ayesa-Arriola, de la Foz, Setien-Suero, Ramirez-Bonilla, Suarez-Pinilla, Son and Crespo-Facorro2020). Despite the age of onset and premorbid functional differences, generally these studies of first episode schizophrenia (FES) a term we use for brevity that includes individuals with schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorder, found few or no sex differences in demographic variables, most types of symptoms, and functioning at study entry. However, the findings are mixed for duration of untreated psychosis (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Hui, Tang, Wong, Lam, Chan and Chen2011; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Leung, Chang, Chan, Lee and Chen2016; Thorup et al., Reference Thorup, Petersen, Jeppesen, Ohlenschlaeger, Christensen, Krarup and Nordentoft2007, Reference Thorup, Albert, Bertelsen, Petersen, Jeppesen, Le Quack and Nordentoft2014). Given its prominent role, premorbid adjustment might be a potential mediator of the relationship between sex and functional outcome.

While there are few sex differences reported in positive symptoms, males reportedly have higher levels of negative symptoms while females show higher levels of mood symptoms such as depression and anxiety (Thorup et al., Reference Thorup, Albert, Bertelsen, Petersen, Jeppesen, Le Quack and Nordentoft2014). In fact, Cotton et al. (Reference Cotton, Lambert, Schimmelmann, Foley, Morley, McGorry and Conus2009) found that women presented with higher levels of affective symptoms in general than did men. In contrast, Szymanski et al. (Reference Szymanski, Lieberman, Alvir, Mayerhoff, Loebel, Geisler and Cooper1995) found in individuals with schizophrenia admitted for the first time, that women compared to men presented with more anxiety, but also illogical thinking, inappropriate affect, and bizarre behavior. However, in one study no gender differences were found (Barajas, Ochoa, Obiols, & Lalucat-Jo, Reference Barajas, Ochoa, Obiols and Lalucat-Jo2015). In any event, a review of FES studies concluded that males generally had more negative symptoms and females had more mood symptoms while there were little or no differences found in positive symptoms (Ochoa et al., Reference Ochoa, Usall, Cobo, Labad and Kulkarni2012). Given the prominent role that negative symptoms play in functional outcome, negative symptoms might be a potential mediator of the relationship between sex and functional outcome.

The literature on cognitive deficits in FES is comparable with that on multi-episode patients showing that cognitive deficits are present (Mesholam-Gately, Giuliano, Goff, Faraone, & Seidman, Reference Mesholam-Gately, Giuliano, Goff, Faraone and Seidman2009) and that there is a relationship between neurocognitive and social cognitive functioning and outcome in first episode patients (Fu, Czajkowski, Rund, & Torgalsbøen, Reference Fu, Czajkowski, Rund and Torgalsbøen2017; Horan et al., Reference Horan, Green, DeGroot, Fiske, Hellemann, Kee and Nuechterlein2012; Milev, Reference Milev2005). Further, FES studies show that males perform better in the domain of visual perception while females perform better in domains such as verbal learning and memory (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Czajkowski, Rund and Torgalsbøen2017; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Leung, Chang, Chan, Lee and Chen2016; Pu et al., Reference Pu, Qiu, Zhou, Yang, Lu, Wang and Yu2019; Torgalsbøen, Mohn, & Rund, Reference Torgalsbøen, Mohn and Rund2014; Yang, Gao, Xiong, & Zhang, Reference Yang, Gao, Xiong and Zhang2021). In one of the largest studies of sex differences in FES, late onset male patients were found to be more impaired than females on measures of verbal memory, executive functions, and other areas of cognitive performance (Ayesa-Arriola et al., Reference Ayesa-Arriola, de la Foz, Setien-Suero, Ramirez-Bonilla, Suarez-Pinilla, Son and Crespo-Facorro2020). Studies suggest that the superior social cognitive performance of females is not present in individuals with FES (Danaher, Allott, Killackey, Hester, & Cotton, Reference Danaher, Allott, Killackey, Hester and Cotton2018; Navarra-Ventura et al., Reference Navarra-Ventura, Fernandez-Gonzalo, Turon, Pousa, Palao, Cardoner and Jodar2018; Verdaguer-Rodríguez et al., Reference Verdaguer-Rodríguez, López-Carrilero, Ferrer-Quintero, García-Mieres, Díaz-Cutraro, Grasa and Peláez2021) for a review see Mote and Kring (Reference Mote and Kring2016). In the general population, women on average perform somewhat better on verbal tasks while men perform somewhat better on visuospatial tasks (Kern et al., Reference Kern, Green, Fiske, Kee, Lee, Sergi and Nuechterlein2008a, Reference Kern, Nuechterlein, Green, Baade, Fenton, Gold and Marder2008b; Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Siedentopf, Hofer, Deisenhammer, Hoptman, Kremser and Delazer2003). Several studies that examined neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia did not include a healthy control group and/or did not correct for sex differences in the general population. Whether these effects are present in schizophrenia to a larger extent than in the general population is not clear (Lewine, Thurston-Snoha, & Ardery, Reference Lewine, Thurston-Snoha and Ardery2006). Thus, whether the conclusions regarding sex differences in neurocognition for schizophrenia patients reflect the impact of schizophrenia or general population sex differences is difficult to determine.

There is still much to be learned about sex differences in insight for individuals with first episode psychotic disorders. In a prospective study using structured assessments, FES women as compared with men showed better insight into psychotic illness (McEvoy et al., Reference McEvoy, Johnson, Perkins, Lieberman, Hamer, Keefe and Sharma2006). However, additional studies of FES individuals that also used structured assessments did not find significant sex differences in global awareness of having a mental disorder (Ayesa-Arriola et al., Reference Ayesa-Arriola, Rodriguez-Sanchez, Morelli, Pelayo-Teran, Perez-Iglesias, Mata and Crespo-Facorro2011; Keshavan, Rabinowitz, DeSmedt, Harvey, & Schooler, Reference Keshavan, Rabinowitz, DeSmedt, Harvey and Schooler2004; Mutsatsa, Joyce, Hutton, & Barnes, Reference Mutsatsa, Joyce, Hutton and Barnes2006). The possibility that there are sex differences in insight early in the course of schizophrenia is important because a large body of evidence in schizophrenia links better insight with lower levels of symptoms and better functioning. Better insight among females, if present, could be a good prognostic sign and help explain the better course, outcomes, and recovery rates seen in females. Given the prominent role for insight in functional outcome, insight might be a potential mediator of the relationship between sex and functional outcome.

We hypothesized that FES males compared to females have poorer premorbid adjustment, an earlier age of onset, poorer insight into their illness, poorer baseline role and social functioning, and higher baseline levels of negative symptoms. Further, we planned to examine these variables as potential mediators of the relationship between sex and functional outcome to provide additional information regarding pathways by which sex influences early functional outcome in schizophrenia.

Methods

Participants

The patient sample consisted of 137 individuals with schizophrenia, schizophreniform, or schizoaffective disorder-depressed type, including 105 males (77%) and 32 females (23%). The mean age at study entry was 22.0 (s.d. = 4.1) years, the mean education was 12.5 (1.7) years, and most patients were single (n = 131; 86%). All participants received outpatient psychiatric treatment at the UCLA Aftercare Research Program and were participants in the fourth phase of the Developmental Processes in Schizophrenic Disorders Project (Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Ventura, Subotnik, Gretchen-Doorly, Turner, Casaus and Medalia2020; Subotnik et al., Reference Subotnik, Casaus, Ventura, Luo, Hellemann, Gretchen-Doorly and Nuechterlein2015). This study was approved by the UCLA Office for Human Research Protections, and all participants gave written informed consent. Diagnosis was established by trained and certified research assessment staff through the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV) plus supplementary information from family members and treating professionals.

Entry criteria were: (1) an onset of psychotic illness within 2 years of study entry; (2) a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder-depressed type, or schizophreniform disorder; (3) 18 to 45 years of age; (4) no evidence of a known neurological disorder; (5) no evidence of significant and habitual drug abuse or alcoholism in the 6 months prior to study entry and that the psychosis was substance-induced; (6) premorbid IQ not less than 70; (7) sufficient fluency in English to avoid invalidating research measures; and (8) treatment with risperidone was not contraindicated.

Normal comparison subjects were recruited through the use of flyers and advertisements which were placed in community sites and local newspapers. Normal comparison participants were chosen on the basis of age, sex, race/ethnicity, handedness, parental education, and community of residence that were comparable to those of the patient sample. Potential normal comparison subjects were assessed using the SCID-IV, sections of SCID-II for Personality Disorders, and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). The eligibility criteria included: no major psychiatric disorder except for a single episode of major depression, no personality disorder, no family history of a major psychotic disorder, and no current of substance use or history substance dependence.

Procedures

Study Entry was defined as the time point in which the patient enrolled in the study. Baseline occurred about 2–3 months after study entry and the 6-month point occurred subsequent to the baseline assessment.

Measures

Psychiatric history, premorbid adjustment, symptoms, and functioning

UCLA Psychiatric and Social History Schedule (P&SH). Demographic and premorbid history data were collected at study entry using a comprehensive form developed by the study team. P&SH data that were collected included age, sex, marital status, race, age of onset, patient and parental years of education, first appearance of prodromal and psychotic symptoms, and treatment history as well as additional psychiatric history variables.

Cannon-Spoor Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS) (Cannon-Spoor, Potkin, & Wyatt, Reference Cannon-Spoor, Potkin and Wyatt1982). The PAS domains include four developmental periods: (1) Childhood (up to age 11); (2) Early adolescence (ages 12 to 15); (3) Late adolescence (ages 17 to 18); and (4) Adulthood (age 19 and above). The PAS also includes five domains of psychosocial adjustment: (1) Sociability and withdrawal; (2) Peer relationships; (3) Scholastic performance; (4) Adaptation to school; and (e) Social-sexual aspects of life. A semi-structured interview accompanies the PAS items which are rated from 0 to 6 based on an interview with the patient and from all sources of information, e.g., the patient's parents, and school and medical records. The PAS was administered at baseline. We examined the summary scores for developmental periods for this study. Higher scores indicate more severe developmental delay.

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Ventura, Green, Shaner, & Liberman, Reference Ventura, Green, Shaner and Liberman1993a) The BPRS was used to examine severity levels in positive, negative, depression-anxiety, and manic symptoms (Ventura et al., Reference Ventura, Lukoff, Nuechterlein, Liberman, Green and Shaner1993b). Each BPRS rater achieved a median Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) of 0.80 or higher across all BPRS items compared with a set of criterion ratings and participated in a quality assurance program. The BPRS is separated into factors (Ventura, Nuechterlein, Subotnik, Gutkind, & Gilbert, Reference Ventura, Nuechterlein, Subotnik, Gutkind and Gilbert2000) that include: Positive Symptoms (Unusual Thought Content, Hallucinations, and Conceptual Disorganization), Negative Symptoms (Blunted Affect, Emotional Withdrawal, and Motor Retardation), and Depression-Anxiety (Depression, Anxiety, Guilt). The BPRS ratings were administered at Study Entry.

Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (Andreasen, Reference Andreasen1984). The SANS is a 25-item measure that is widely used to assess two negative symptom domains: (1) Expressive Symptoms, which consisted of Affective Flattening (blunted affect) and Alogia, and (2) Experiential Symptoms, which consisted of Avolition/Apathy and Anhedonia/Asociality. The SANS was administered every 3 months by raters who were trained to criterion levels of ICC = 0.75 or higher on either the Global Items or all SANS items (Ventura et al., Reference Ventura, Green, Shaner and Liberman1993a).

Global Functioning Scale: Role (GFS: Role) and Global Functioning Scale: Social (GFS: Social) (Cornblatt et al., Reference Cornblatt, Auther, Niendam, Smith, Zinberg, Bearden and Cannon2007; Niendam, Bearden, Johnson, & Cannon, Reference Niendam, Bearden, Johnson and Cannon2006). The GFS: Role is a 10-point rating scale that measures a combination of the quantity and quality of work/school functioning. The GFS: Social is a 10-point rating scale that measures a combination of the quantity and quality of social interactions with family and friends. Both versions of the GFS ratings were completed at study entry and at 6 months based on their ongoing interactions with the patients and family members. Raters were individual therapists who were trained raters, with mean ICC of ICC = 0.91 for GRS: Role and ICC = 0.76 for the GFS: Social.

Neurocognition and social cognition

MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) was administered at Baseline to provide a standardized assessment of cognitive functioning (Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Green, Kern, Baade, Barch, Cohen and Marder2008). This battery assesses seven domains: Speed of Processing, Attention/Vigilance, Working Memory, Verbal Learning, Visual Learning, Reasoning and Problem Solving, and Social Cognition. The dependent variable was the MCCB Overall Composite Score and the individual domain scores for which we used a scaled T scores based on a community sample (Kern et al., Reference Kern, Nuechterlein, Green, Baade, Fenton, Gold and Marder2008b). Due to the focus on sex differences, we did not use T scores corrected for gender and age.

The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT) Part III uses video clips depicted individuals either lying or expressing sarcasm (McDonald, Flanagan, Rollins, & Kinch, Reference McDonald, Flanagan, Rollins and Kinch2003). After each item (video clip and hint), the participants were asked four questions meant to gauge their ability to make inferences about the characters' actions, intentions, thoughts and feelings. A total score was calculated across lie and sarcasm items (Kern et al., Reference Kern, Green, Fiske, Kee, Lee, Sergi and Nuechterlein2008a).

Relationships Across Domains (RAD) is a 75-item paper-and-pencil assessment of an individual's perception of various aspects of relationships. The RAD has good internal consistency in schizophrenia patients and normal controls (Sergi et al., Reference Sergi, Fiske, Horan, Kern, Kee, Subotnik and Green2009). The RAD reflects the ability of individuals to use their implicit knowledge of four relational models to comprehend social relationships and infer the behavior of social partners. The RAD contains 25 vignettes. After each vignette, participants were asked yes-no questions that evaluate their implicit knowledge of the relational model. The dependent measure was the total score across the four relational models.

Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test 2.0 (MSCEIT) is a self-report measure consisting of 141 items and 8 subscales that evaluate four components (branches) of emotion processing (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, Reference Mayer, Salovey and Caruso2002). The MSCEIT has been shown to demonstrate good reliability and discriminant validity in schizophrenia (Eack et al., Reference Eack, Greeno, Pogue-Geile, Newhill, Hogarty and Keshavan2010; Eack, Greeno, Christian-Michaels, Dennis, & Anderson, Reference Eack, Greeno, Christian-Michaels, Dennis and Anderson2009; Kee et al., Reference Kee, Horan, Salovey, Kern, Sergi, Fiske and Green2009). The MISCEIT contains four branches: Identifying Emotions, Using Emotions, Understanding Emotions, and Managing Emotions. In this study we used a global measure from the MSCEIT, Emotional IQ (EIQ).

Insight

Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD) (Amador, Strauss, Yale, & Gorman, Reference Amador, Strauss, Yale and Gorman1993) is a multi-dimensional scale based on a semi-structured interview. The SUMD items and subscales define specific components of insight – General Unawareness of (Having a) Mental Disorder, Unawareness of the Achieved Effects of Medication, Unawareness of Symptoms, Misattribution of Symptoms, and Unawareness of the Social Consequences of (Having a) Mental Disorder. To reduce the number of relationships examined, we chose one primary variable to approximate overall insight, i.e., General Unawareness of (Having a) Mental Disorder. This primary item represents an individual's lack of understanding that the symptoms or experiences of the prior psychotic episode at study entry were part of a mental illness. SUMD items are scored from 1 (aware) to 5 (unaware) so higher scores indicate greater unawareness. Additional components of unawareness were examined in secondary analyses after the primary variable of general unawareness of mental disorders was analyzed for a sex difference.

Statistical approach

We conducted t test, ANOVA, and Chi-square analyses to examine sex differences between male and female first-episode schizophrenia patients on variables collected during Study Entry, Baseline, and at 6 months after baseline.

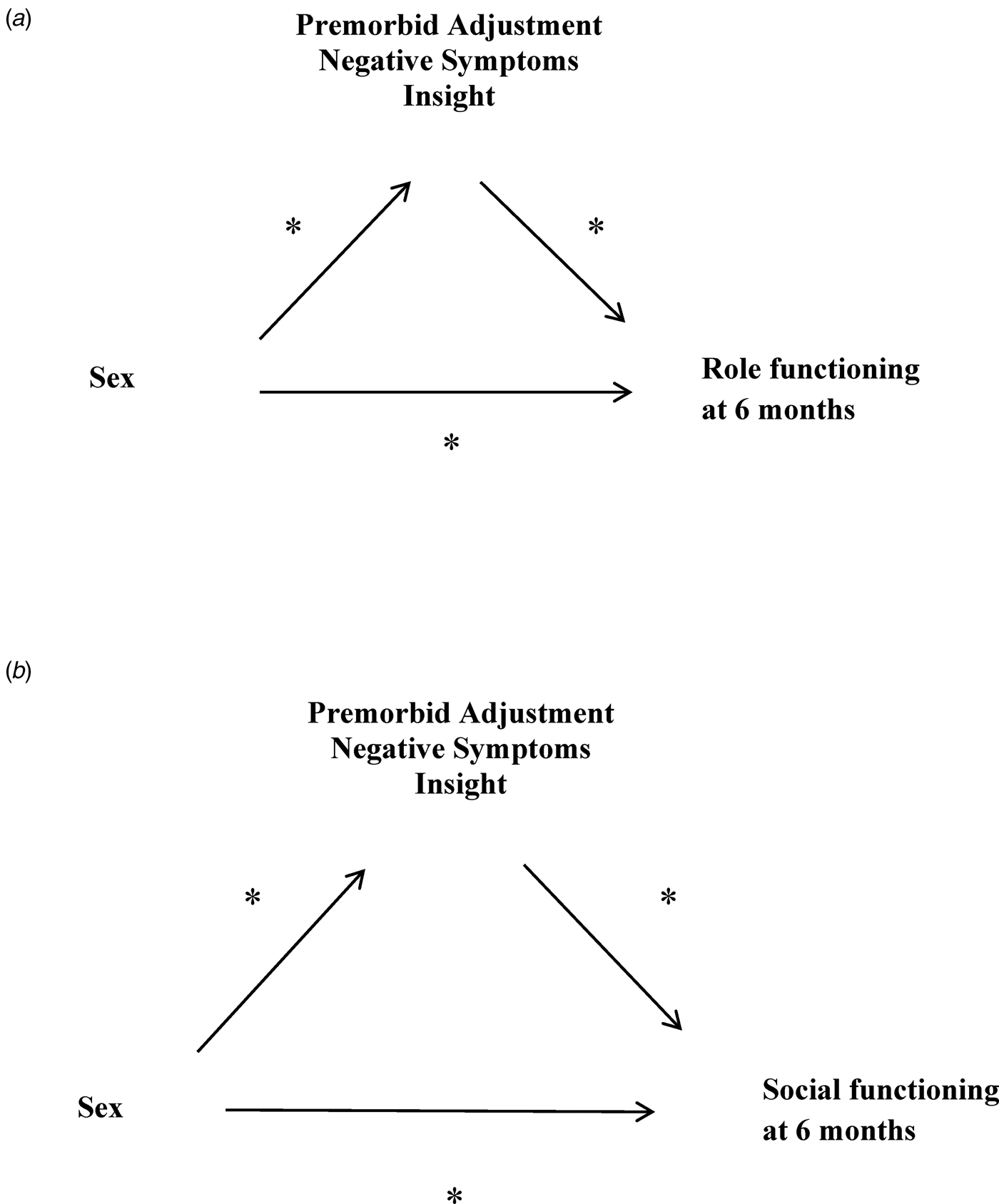

There were significant relationships among several potential predictor variables such as premorbid adjustment, negative symptoms, and insight measured at baseline in relationship to role and social functioning at 6 months. Mediation analyses (Model One) were used to evaluate whether the relationship between sex and role functioning (school and work) was mediated by these predictor variables (Fig. 1a). We also examined (Model Two) the indirect effect of premorbid adjustment, negative symptoms, or insight on the relationship between sex and social functioning (friends and family) (Fig.1b). Analyses were conducted on functioning at the 6-month point. We followed the well-established procedures and conceptual understanding for mediation provided by Baron and Kenny (Reference Baron and Kenny1986) and using bootstrap confidence intervals for the indirect effects of the mediators (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2004).

Fig. 1. (a) Model one examines role functioning at 6 months. Examination of potential mediators of the relationship between sex and role functioning (school and work) at 6-months using a boot strapping method to generate confidence intervals. (b) Model two examines social functioning at 6 months. Examination of potential mediators of the relationship between sex and social functioning (family and friends) at 6-months using a boot strapping method to generate confidence intervals.

Results

Demographic information and a statistical analysis of sample characteristics can be found in Table 1 which contains a list of variables, means, standard deviations, F or t test values, and p values.

Table 1. Sex differences in demographic, premorbid adjustment, clinical, symptom, and insight variables in individuals with first episode schizophrenia, total n = 137

a Cannon-Spoor Premorbid Adjustment Scale.

b Psychiatric and Social History Form.

c Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).

d Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)

e Global Functioning Scale: Social and Role.

f Scale to assess unawareness of mental disorder; for GFS analyses at 6 months, total n = 84, n = 60 males; n = 24 females.

We found that males compared to females had lower levels of premorbid adjustment across the four key developmental periods including Childhood (p = 0.015), Early Adolescence (p = 0.019), Late Adolescence (p = 0.010), and Adulthood (p = 0.004), and had an earlier age of onset, M = 21.7 (s.d. = 3.2) v. 23.7 (s.d. = 4.8), p = 0.004 (Table 1). In keeping with the analyses of premorbid adjustment, we found at study entry that males were rated lower than females in Role Functioning (p = 0.002) and Social Functioning (p = 0.034) and at 6 months (Table 1). Symptom assessments at study entry indicated that males as compared to females exhibited higher levels of negative symptoms (p = 0.044), but that there were no differences between the two groups in positive symptoms (p = 0.684) or mood symptoms (p = 0.372). In addition, we found that at baseline females had better insight than males (p = 0.018; Table 1) in that they scored lower on Unawareness of Having a Mental Disorder. Also, secondary analyses revealed that females were significantly lower (better insight) than males on Unawareness of the Benefits of Medication, Unawareness of Past Delusions, and Unawareness of the Social Consequences of Having a Mental Disorder (Table 1).

Because sex differences in some cognitive domains tend to be present in the general population, we examined cognitive functioning on the MCCB at baseline through Diagnosis (Schizophrenia v. Healthy Comparison) × Sex (Male v. Female) ANOVAs (Table 2). We found no significant Diagnosis × Sex interactions for the Overall Composite Score or any domain score. Further, there were no statistically significant Diagnosis × Sex interactions at baseline on any of the measures of social cognition. As expected, both male and female patients performed more poorly compared to their respective control group.

Table 2. Examination of sex differences in neurocognition and social cognition in individuals with first episode schizophrenia compared with healthy controls T score means and s.d.

a MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) T scores are uncorrected for age and gender.

b The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT).

c Relationships Across Domains (RAD).

d Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test 2.0 (MSCEIT); Patients: MCCB n = 98, TASIT n = 82; RAD; n = 83; MSCEIT n = 86; Controls: MCCB n = 92, TASIT n = 39, RAD n = 52, MSCEIT n = 45.

Given the significant sex differences in premorbid adjustment, and baseline negative symptoms and insight we conducted correlational analyses which indicated that better total premorbid adjustment was predictive of better role and social functioning at 6 months (Table 3). Lower negative symptoms as measured by the SANS were correlated with higher role functioning at 6 months and higher social functioning at 6 months (Table 3). In addition, correlational analyses indicated that better insight into having a mental illness at baseline was predictive of better role and social functioning 6 months later.

Table 3. Examination of baseline predictors of 3 month and 6 month role and social functioning in individuals with first episode schizophrenia (n = 84)

*p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; + p < 0.10; n = 60 males; n = 24 females.

Mediation analysis

We conducted analyses to determine if the relationship between sex and role functioning (work or school) at 6 months was mediated by any of three potential mediators: premorbid adjustment, negative symptoms, and insight (see Fig. 1 for model). The mediation path (indirect effect) through premorbid adjustment was significant (95% CI 0.22–1.4). After taking the mediation path through premorbid adjustment into account, sex does still have a direct effect on the outcome (95% CI 0.42–2.94) so premorbid adjustment is considered a partial mediator. The mediation path (indirect effect) through insight was significant (95% CI 0.00–0.74). After taking the mediation path through insight into account, sex does still have a direct effect on the outcome (95% CI 0.80–3.22) so insight was considered a partial mediator. However, the mediation path (indirect effect) through negative symptoms was not significant (95% CI −0.17 to 0.76).

We also conducted analyses to determine if the relationship between sex and social functioning at 6 months was mediated by any of the same three potential mediators (see Fig. 1b for model). The mediation path (indirect effect) through premorbid adjustment was significant (95% CI 0.02–0.86). After taking the mediation path through premorbid adjustment into account, sex does not have a direct effect on the outcome (95% CI −0.040 to 2.09) so premorbid adjustment is a full mediator. The mediation path (indirect effect) of insight was significant (95% CI 0.074–0.927). After taking the mediation path through insight into account, sex does not have a direct effect on the social functioning (95% CI −0.29 to 1.52) so insight is considered a full mediator. However, the mediation path (indirect effect) through negative symptoms was not significant (95% CI −0.15 to 0.96).

Discussion

Our analyses are consistent with prior studies showing robust sex differences in a rigorously defined cohort of FES patients across several developmental, clinical, insight, and functional domains. Male individuals compared to females had lower levels of premorbid adjustment, an earlier age of onset, higher levels of negative symptoms, and lower levels of social and work functioning. In contrast, there were no sex differences in positive or mood symptoms. At study entry, females had better insight into having a mental illness and better insight into the benefits of medication and the social consequences of a disorder. Differences in premorbid adjustment, negative symptoms, and insight significantly predicted role and social functioning at 6 months for the entire sample. One key finding of our study is that premorbid adjustment and insight were mediators of the relationship between sex and functional outcome (role and social), while negative symptoms were not. Specifically, the mediation analyses indicate that pathways from the patient's sex to role and social functioning (school and work) go through premorbid adjustment and insight, suggesting that higher levels of functioning observed in females can partially be explained by the influence of sex on premorbid adjustment and insight. Although both males and females with schizophrenia performed more poorly than did healthy controls on measures of neurocognition and social cognition, no statistically significant diagnosis by sex interactions were found in cognitive performance.

The important role of premorbid functioning is consistent with prior studies which show an association with a better prognosis in first episode patients (Albert et al., Reference Albert, Bertelsen, Thorup, Petersen, Jeppesen, Le Quack and Nordentoft2011; Amminger et al., Reference Amminger, Henry, Harrigan, Harris, Alvarez-Jimenez, Herrman and McGorry2011). In addition, most studies have found that sex differences in premorbid functioning predict better functioning in women compared to men up to 3 years (Ayesa-Arriola et al., Reference Ayesa-Arriola, de la Foz, Setien-Suero, Ramirez-Bonilla, Suarez-Pinilla, Son and Crespo-Facorro2020). In addition, individuals with schizophrenia with higher levels of premorbid functioning generally demonstrate better treatment response to medications compared to individuals with lower levels (Hatzimanolis et al., Reference Hatzimanolis, Stefanatou, Kattoulas, Ralli, Dimitrakopoulos, Foteli and Stefanis2020; Klein & Rosen, Reference Klein and Rosen1973; Rabinowitz et al., Reference Rabinowitz, Napryeyenko, Burba, Martinez, Neznanov, Fischel and Schreiner2011; Strous et al., Reference Strous, Alvir, Robinson, Gal, Sheitman, Chakos and Lieberman2004).

Males typically have an earlier age of onset (Immonen, Jaaskelainen, Korpela, & Miettunen, Reference Immonen, Jaaskelainen, Korpela and Miettunen2017; Miettunen, Immonen, McGrath, Isohanni, & Jääskeläinen, Reference Miettunen, Immonen, McGrath, Isohanni, Jääskeläinen, de Girolamo, McGorry and Sartorius2019; Neill et al., Reference Neill, Tan, Toh, Selvendra, Morgan, Rossell and Castle2020) and this finding has been extended to first episode patients, for a review see Ochoa (Ochoa et al., Reference Ochoa, Usall, Cobo, Labad and Kulkarni2012). That is consistent with the view that males have a more severe form of the illness compared to females (Abel et al., Reference Abel, Drake and Goldstein2010; Immonen et al., Reference Immonen, Jaaskelainen, Korpela and Miettunen2017; Rabinowitz, Levine, & Hafner, Reference Rabinowitz, Levine and Hafner2006). Indeed, the earlier the onset of symptoms, the less time an individual has to develop socially or academically before functional impairment occurs due to schizophrenia.

The observation of a relationship in our sample between greater baseline insight and higher role and social functioning at 6-months suggests that insight is an important predictor of the early course of schizophrenia. The finding that insight is a mediator of the relationship between premorbid adjustment and role functioning is important because there are sex differences in insight early in the course of schizophrenia and better insight is linked to lower levels of symptoms and better functioning (Cobo et al., Reference Cobo, Nieto, Ochoa, Pousa, Usall, Banos and Ruiz2016, Reference Cobo, Labad, Pousa, Nieto, Ochoa, Usall and Ruiz2020; Pousa et al., Reference Pousa, Ochoa, Cobo, Nieto, Usall, Gonzalez and Usall2017; Ramu, Kolliakou, Sanyal, Patel, & Stewart, Reference Ramu, Kolliakou, Sanyal, Patel and Stewart2019). Insight into one's illness indicates the ability to reflect on one's experiences, which is likely related to the ability to understand the experiences of others as well. These Theory of Mind skills are related to better insight (Subotnik et al., Reference Subotnik, Ventura, Hellemann, Zito, Agee and Nuechterlein2020). Thus, the better awareness of a mental disorder in females at baseline might help to explain their better course and functional outcome. The implication is that EIS for people with schizophrenia might focus more attention for males on the development of insight, as this may lead to better functional outcome.

Broader issues in sex-related cultural stereotypes in expectations of males compared to females might interact with the clinical mediators we identified to influence the course of the illness. Congruent with gender stereotype theory, adolescent men may feel greater pressure to leave home and begin a career at an earlier age than do females (Hentschel, Heilman, & Peus, Reference Hentschel, Heilman and Peus2019). Also, several investigators have hypothesized that females tend to possess stereotypically female gender traits, such as acceptance of their illness and treatment adherence, while males tend to exhibit more socially adverse and self-destructive behaviors and attitudes (Morgan, Castle, & Jablensky, Reference Morgan, Castle and Jablensky2008; Riecher-Rössler & Häfner, Reference Riecher-Rössler and Häfner2000). The greater insight into having a mental illness that we found in females may represent an aspect of this acceptance of illness. On a related topic, whether socioeconomic or cultural influences on gender identity are a stronger influence than sex at birth on premorbid adjustment and insight into illness needs more investigation (Lewine et al., Reference Lewine, Thurston-Snoha and Ardery2006).

Biological factors may also act as a mediator which could be an additional influence on the more favorable course observed in females compared with males with schizophrenia. In fact, the level of estrogen has been suggested as a protective factor (da Silva & Ravindran, Reference da Silva and Ravindran2015; Falkenberg & Tracy, Reference Falkenberg and Tracy2014; Gogos et al., Reference Gogos, Sbisa, Sun, Gibbons, Udawela and Dean2015; Hafner et al., Reference Hafner, Maurer, Loffler, Fatkenheuer, an der Heiden, Riecher-Rossler and Gattaz1994; Salem & Kring, Reference Salem and Kring1998). The estrogen hypothesis postulates that the vulnerability threshold for schizophrenia is mediated by the estrogen levels in women until menopause (Abel et al., Reference Abel, Drake and Goldstein2010; Gogos et al., Reference Gogos, Sbisa, Sun, Gibbons, Udawela and Dean2015; Olsen et al., Reference Olsen, Hansen, Jakobsen, Djurovic, Melle, Agartz and Werge2008). Estrogen is known to protect against prenatal complications and excessive synaptic pruning and may also have a antipsychotic-like effect by impacting post-synaptic dopaminergic signal transduction and reducing dopamine-mediated psychotic symptoms (Seeman, Reference Seeman2012). Hence, the modulating role of estrogen may be an additional factor in the later onset, better role and social functioning, and lower levels of negative symptoms observed in the early phase of illness.

We did not find any Diagnosis by Sex interactions in neurocognitive or social cognitive performance. Some prior studies that found sex differences in cognition among schizophrenia patients did not include a healthy control group and did not use cognitive scores that were corrected for sex differences in the general population. Thus, many of the prior reports of sex differences in cognitive performance among schizophrenia patients might be due to general population differences rather than to the impact of schizophrenia.

The study had some limitations. Some patients may not accurately recall how long ago their psychotic symptoms began. We believe that our use of parental and professional reports as well as medical records to minimize this issue. As is the case with many studies of individuals with schizophrenia, our sample size for females is smaller than for males. However, we were able to detect significant sex differences with this sample size of females. Because we received most of our referrals from hospitals at which patients were acutely ill, sample selection may favor those patients who required a hospitalization. Men or women who never needed hospitalization may therefore be underrepresented. Our sample consists of individuals who are willing to participate in clinical research. However, how these factors would differentially impact participation of males v. females to produce the sex differences we found is not obvious.

To summarize, in examining sex differences between males and female individuals with schizophrenia, we found many elements of consistency with the prior literature which indicates that males have poorer premorbid adjustment, an earlier age of onset, higher negative symptoms, and lower levels of role and social functioning. We found that predictors of functioning, such as premorbid adjustment and insight partially mediated the relationship between sex and role functioning and fully mediated the relationship between sex and social functioning. These findings underscore that males are more impaired than females and have prognostic implications for the impact of sex on the early course of schizophrenia.