Doctors spend much of their time learning. When they qualify they may have spent nearly 20 years in full-time education. They will have been tested at various stages and become used to the idea of acquiring the knowledge that examiners expect of them. Learning, however, continues, both in the acquisition of skills needed in the clinical area and the facts needed to satisfy higher professional examiners. Doctors are almost unique among other professional groups in the number of examinations they sit and with the emergence of clinical governance there is an added weight placed upon lifelong learning. So, doctors need to continue learning. A better understanding of the way in which they learn must be valuable.

The business world has been interested in the idea of learning styles since the Second World War, with the Learning Styles Inventory devised by Kolb et al (Reference Kolb, Rubin and McIntyre1984) being the most widely-used tool. Although formulated to study organisational behaviour in the business environment, it is equally applicable to medical practitioners, both for doctors in training (Reference Gatrell and WhiteGatrell & White, 1999) and as a reflective tool used by experienced consultants (Reference BrigdenBrigden, 1999).

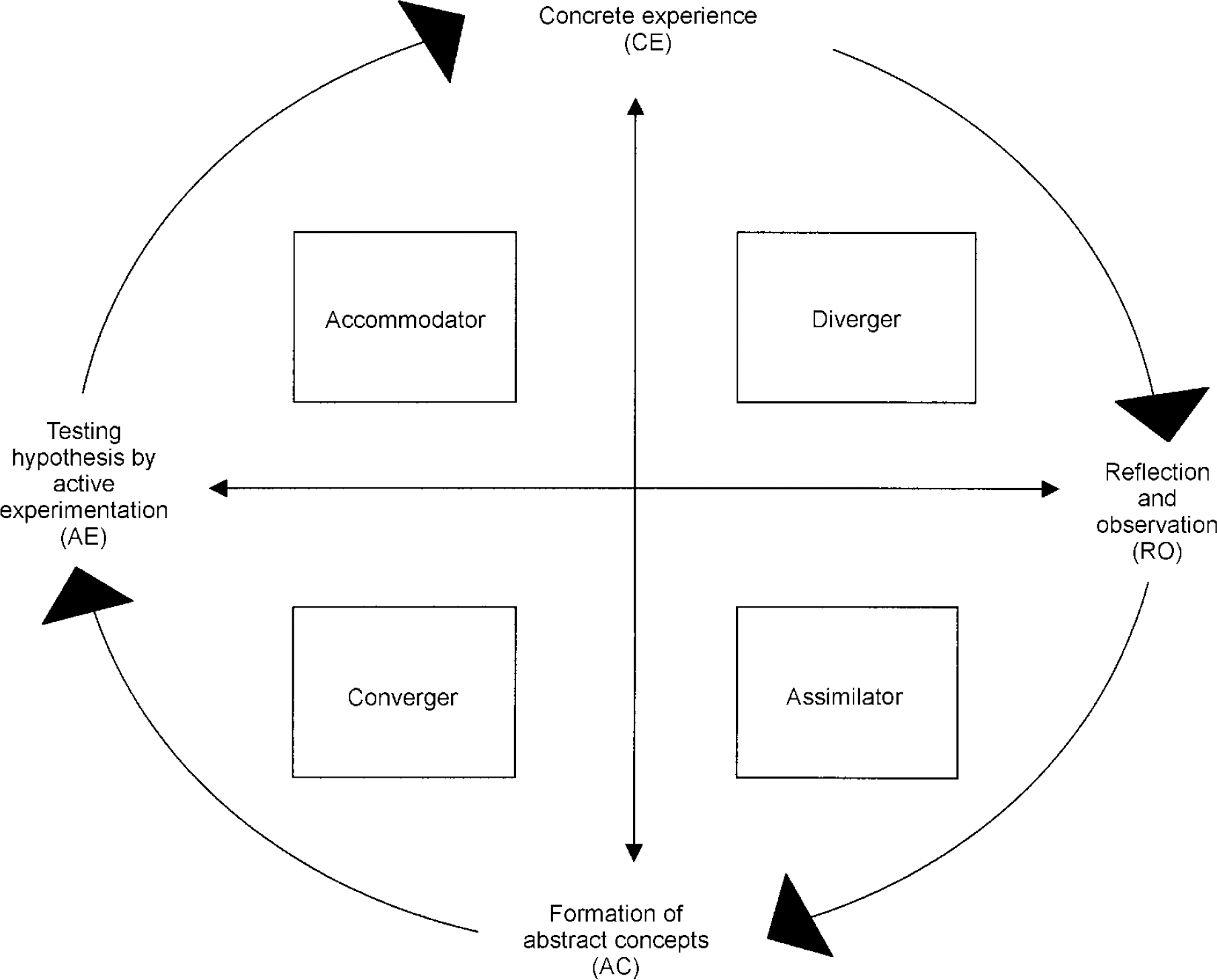

Kolb et al postulate learning as a four-stage cycle (see Fig. 1). The individual has experiences upon which he or she reflects and makes observations. These are then used to form concepts and generalisations. Experimental actions follow and these, in their turn, create new experiences. The Learning Styles Inventory described by Kolb et al (Reference Kolb, Rubin and McIntyre1984) measures individual strengths and weaknesses of the learner in these four stages (or modes) of the learning process. It is a simple self-description test that has nine sets of four descriptions with the respondent marking words that are most, through to least, like him- or herself. This then generates two axes, one being active experimentation (AE) v. reflective observation (RO), the other being concrete experience (CE) v. abstract conceptualisation (AC). These axes are then plotted out to give the four learning styles described in Fig. 1. For example, one set of four words is ‘feeling, watching, thinking and doing’, which reflect CE, RO, AC and AE, respectively.

Fig. 1. Learning as a four stage cycle, with the four learning styles: converger, diverger, assimilator and accommodator

Converger: knowledge focused on specific problems. Use abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation in problem solving, decision-making and the practical application of ideas. Prefer to deal with technical tasks rather than social and interpersonal issues. Style characteristic of engineers and technical specialists.

Diverger: opposite strengths to the converger, emphasises concrete experience and reflective observations. View situations from many perspectives and organise relationships into a meaningful ‘gestalt’. Style characteristic of counsellors and personnel managers.

Assimilator: by combining abstract conceptualisation and reflective observations are able to create theoretical models and assimilate observations into an integrated explanation. Style characteristic of mathematicians and those in research and planning departments.

Accommodator: opposite strengths to the assimilator, emphasises concrete experience and active experimentation. Intuitive trial and error approach; action orientated and adapt well to changing circumstances. Style characteristic of business world, especially marketing and sales. Based on Reference Kolb, Rubin and McIntyreKolb et al. 1984.

The study

Senior and specialist registrars of all specialities working in the South and West Region are encouraged to attend the 6-day management course organised locally by the Postgraduate Dean. Selection bias is unlikely to be an issue because all trainees are expected to attend a management course. The majority of doctors elect to attend this particular course. Over the past 4 years 272 such doctors have attended the course and as part of the programme have completed the Learning Styles Inventory, as described above.

The nine questions and scoring instructions were distributed to the participants, who then completed and scored their responses. The results were plotted and individual learning styles recorded by the course organiser.

Findings

Table 1 shows the higher professional trainees divided by speciality and the number within each professional group recording each of the four types of learning style. Half scores are possible where the individual fell exactly on the dividing line between two different styles. It can be seen that all specialities, except psychiatry, have convergence as the most numerous category. Psychiatrists' learning styles were more evenly spread, the most numerous category being divergers at 32% of the total. The data were further analysed by separating the scores according to the two axes described above, axis one being AE as opposed to RO with axis two being CE as opposed to AC (Table 2). If the results of psychiatrists are compared with the pooled results of all the specialities collectively, there is a significant difference in scores on both these scales. Generally the whole sample favours AE, with psychiatry split more evenly between this and RO (P=0.03). Differences are even more marked in axis two with specialist/senior registrars in general favouring AC while those from psychiatry favour CE (P=0.01). For surgeons, there is also significant variation in their scoring on both scales (P=0.03, 0.01) and it is in the opposite direction to psychiatrists. The two modes that contribute to the converger style (AE and AC) are more prevalent in surgeons when compared to the group as a whole and less prevalent in psychiatrists. All probabilities were calculated using χ2 tables.

Table 1. Learning styles of the different specialities

| n in each learning style (% of each row) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speciality | Convergence | Divergence | Assimilation | Accommodation | Total |

| Medicine | 16 (50) | 6 (19) | 6 (19) | 4 (13) | 32 |

| Surgery | 43 (69) | 4 (6) | 8 (13) | 7 (11) | 62 |

| Anaesthetics | 21.5 (58) | 5.5 (15) | 2.5 (7) | 7.5 (20) | 37 |

| Psychiatry | 9 (21) | 13.5 (32) | 8.5 (20) | 11 (26) | 42 |

| Paediatrics | 14.5 (39) | 8 (22) | 4.5 (12) | 10 (27) | 37 |

| Others | 25 (40) | 11 (18) | 14 (23) | 12 (19) | 62 |

| Total | 129 (47) | 48 (18) | 43.5 (16) | 51.5 (19) | 272 |

Table 2. The two axes of learning style: psychiatrists and surgeons compared to the group as a whole

| Surgery n=62 | All n=272 | Psychiatry n=42 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis one | Active experimentation (as opposed to reflective observation) | 50* | 81% | 180.5 | 66% | 20* | 48% |

| Axis two | Abstract conceptualisation (as opposed to concrete experience) | 51** | 82% | 172.5 | 63% | 17.5** | 42% |

Comments

The ‘popularity’ of convergers in the medical profession has been demonstrated in research on surgical trainees (Reference Drew, Cule and GoughDrew et al, 1998), paediatricians (Reference KosowerKosower, 1995) and medical students (Reference Lynch, Woelfl and SteeleLynch et al, 1998). The results suggest that psychiatrists approach learning and problem solving in a different way to other doctors in general and surgeons in particular. This has a number of implications.

First, in the liaison psychiatry setting the psychiatrist may approach a clinical problem in a very different way to the other specialists involved. Convergers seem to work best when there is a single correct answer or solution to a question or problem, as can be seen with surgeons. Divergers can organise many relationships into one meaningful ‘gestalt’, an invaluable approach for a psychiatrist. It is to be imagined that this could potentially create conflict between specialities over patient management, and it is known that non-psychiatric doctors view the psychiatric consultation in a very different way to the psychiatrist (Reference Cohen-Cole and FriedmanCohen-Cole, 1982).

Second, it is known that medical students commonly have a negative view of psychiatry, regarding the speciality as unscientific, different from medicine generally and not using medical skills (Reference Creed and GoldbergCreed & Goldberg, 1987). The work of Lynch et al (Reference Lynch, Woelfl and Steele1998) showed that in a sample of medical students, 45% were convergers, 26% assimilators, 21% accommodators and only 8% were divergers. So, for example, 66% of students are convergers or accommodators and are thus drawn to AE. Psychiatrists are less likely to espouse this stage of the learning process and may approach teaching in a way that dwells on reflective observation, their preferred approach. This is unlikely to be a style that would engage the majority of medical students, and would help to explain the students' negative views of psychiatry. A consideration of this may help engage students with the speciality — both to have a more favourable attitude generally and to consider it as a career.

Third, among all doctors, including those who have chosen psychiatry as a career, there is a need to consider lifelong learning. Using a learning portfolio is one approach to this that helps keep the individual interested and engaged (Reference BrigdenBrigden, 1999). This exercise in reflecting on experience and future objectives can be expressed in terms of different quadrants of the learning cycle. The individual's knowledge of his or her own learning style helps inform this process, helps people to understand why they find some forms of learning more acceptable than others and helps people take full advantage of learning opportunities as they arise (Reference Gatrell and WhiteGatrell & White, 1999).

Finally, it is worth remembering that Kolb et al (Reference Kolb, Rubin and McIntyre1984) suggest that to become a more effective learner one needs to develop competencies in all learning styles. The key to effective learning is to be competent in each mode where appropriate.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.