Introduction

Roughly 90,000 taxi drivers in Beijing learned English in preparation for the Summer Olympic Games (Beijing 2008) of some 600,000 total residents of the city that have jumped on the English bandwagon in the past few years (People's Daily, 2001). China is a country of nearly a billion and a half people, most of whom now begin learning English at the age of ten (Dong, Reference Dong2005: 11). A simple Google search for ‘English in China’ yields more than 36,000,000 results! It cannot be argued that English is unpopular in the Middle Kingdom. With so many learners there, it stands to reason that a variety of English peculiar to China would eventually develop, and there is much evidence to suggest that it has already begun.

Prior to 1978, China was largely cut off from international contact, but the death of Mao Zedong two years earlier allowed for changes within the country's policy structure. From then on, a gradual modernisation programme was instituted that allowed for the development of a more open market economy. Thus, the English Boom was born, and, nowadays, hundreds of thousands of ESL teachers flock to China each year for annual contracts teaching at all levels, from primary upwards. The roles of English extend to all ends of the Chinese social spectrum: mass media to tourism, sport to government. This English Boom has spurred the development of localised varieties, as well as the so-called Chinglish phenomenon. Tourists and foreigners in China often make a habit out of photographing and collecting the ‘funny English’ found on signs around the country. Even Wikipedia has a lengthy article on the subject of Chinglish, with examples and photographs. YouTube is chock full of home-made videos on the subject, and every westerner in China wants to be an expert on the subject. Websites like Engrish (2006) and The Chinglish Files (2008) allow visitors to submit their own personal photos of ‘Chinglished’ signs, funny menus, or unusual product slogans.

All of these factors raise questions about the legitimacy of a localised variety of English that is unique to China. Does such a variety exist? Where do funny, nonsensical mistakes on signage meet valid local developing forms of English? What are Chinglish, Chinese English, and China English and are there any differences between them?

Chinglish, Chinese English, and China English

Based on the research of several noted linguists, including Ge Chuangui (Reference Ge1983) and Li Wenzhong (1993), Wei Yun and Fei Jia (Reference Wei and Fei2003) identify three stages in the development of the English that is spoken in China: Chinese Pidgin English (CPE), Chinglish as an interlanguage, and Chinese/China English (CE) as a developing world variety. While these categories hold much value, the grouping of Chinese and China English together is possibly too broad, and does not take into consideration the existence of entirely nonsensical forms of English that are the result of poor translations. Leaving the largely historical issue of Chinese Pidgin English aside, in this essay I will argue that Chinglish is not, in fact, an interlanguage, but a nonsensical, problematic form of English that is the result of poor translation, misspelling, and errors. Furthermore, I will separate and expand the categories of Chinese English and China English, suggesting that the former is an interlanguage that is used on a learner's path toward fluency and the latter is a developing world variety of English.

In discussing any non-native variety of English, it is first useful to examine Kachru's three circles of English (see Crystal, Reference Crystal1997). With the Inner Circle consisting of the varieties generally considered to be ‘native’ (e.g. UK or American English) and the Outer Circle comprising developed international varieties often found in former English colonies (e.g. India or Singapore), the outermost Expanding Circle will be the concern of this essay. China English, as I shall define it below, falls into this Expanding Circle category, along with Russia and other large geographical areas, making it the potentially largest group of English speakers on earth. Here, we can also talk about the ‘nativisation’ of a variety – how far along the variety is on its path to becoming truly localised. Butler (in Kirkpatrick & Xu, Reference Kirkpatrick and Xu2002) sets out five criteria for nativisation, including a) standard and unique pronunciation, b) a lexicon that expresses local ideas, c) history in the speech community, d) a written literature and e) a set of reference works. I follow Kirkpatrick & Xu's (ibid.) assessment that China English falls into the class of a developing variety rather than an established variety, particularly because China English has, until now, only fulfilled the first three of Butler's criteria. Thus, for the purposes of this essay, China English (as it will be defined below) will be considered as a developing variety in Kachru's Expanding Circle. Several varieties of English have already developed among communities of Chinese speakers in other parts of the world, including Singapore English, Hong Kong English, and Malaysian English. This essay will be limited to the context of Mainland China English only and will not be concerned with the other varieties of Chinese-based English.

Defining Chinglish

As previously stated, Wei & Fei (Reference Wei and Fei2003) define Chinglish as an interlanguage, usually manifested as Chinese-style syntax with English words, Chinese phonological elements in pronunciation or grammatical variations that attempt to follow Standard English rules but miss the mark (p. 43). As will be discussed later in this essay, I assert that these criteria should instead be used to define Chinese English as an interlanguage. Chinglish, then, is a nonsensical form of language, identifiable as an attempt at English, but usually produced by deficient translation devices or speakers/writers with a low skill level (though it may not always be possible to tell which of the two has caused any particular instance of Chinglish). By definition, then, the occurrence of Chinglish is generally confined to written forms where mistakes of expression or translation are made.

Examples of Chinglish

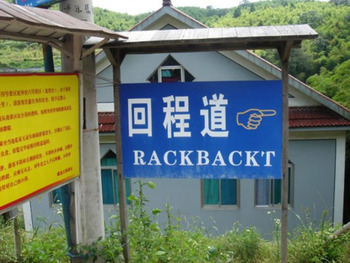

Figure 1 below is an easily definable example of Chinglish as a nonsensical, erroneous form of language. This sign was photographed at the top of a mountain path climb in rural Zhejiang province.

Figure 1. Example of Chinglish

The phrase 回程道 (huíchéng dào) can be glossed as ‘return journey way’ and translated as ‘return route’ or ‘way back’, which makes sense in the light of the sign's positional context, indicating the way back down the mountain. However, the obviously flawed ‘English’ translation listed below the Chinese could hardly be termed anything but nonsensical. The only part of the translation that appears to correlate with the actual Chinese meaning is ‘back’; however, with the preceding ‘rack’ and the suffixed ‘t’ added on, the word makes no sense.

Figure 2, taken near the Da Zha Lan Shopping Alley in Beijing's hutong district, may also be regarded as an example of Chinglish.

Figure 2. Example of Chinglish

Here, the term 智力玩具 (zhìlì wánjù) is translated as ‘mental toy’, while a more appropriate translation would be ‘intellectual toy’. The concept of an ‘intellectual toy’ might arguably be a lexical item exclusive to China, as a Google search of the phrase in English yields only Chinese-based toy manufacturers (compared with ‘educational toy’ in other varieties of English). Thus, the term ‘mental toy’ might be classified as Chinglish because of its nonsensical nature and poor translation.

Figure 3 is a particularly interesting example of Chinglish signage, photographed at the same place as Figure 2, near Da Zha Lan Alley in Beijing.

Figure 3. Example of Chinglish

The three characters 佛光阁 (fó guāng gé) can be literally glossed as ‘Buddha light shelf’ and refer to a small Buddha-shaped lamp that is often manufactured and sold in areas of China frequently visited by tourists. This translation is an obvious case of Chinglish: ‘Buddna’ being a typo of Buddha, ‘sheen’ being a possible interpretation of 光, an adjective meaning shiny or lustrous, and ‘cockloft’ being a very antiquated British word for ‘attic’. When translated through more sophisticated online software (Yellowbridge, 2008), 阁 receives hits as both ‘shelf’ and ‘attic’ which suggests that the phrase was translated via an out-of-date dictionary or software. Hence, this unintelligible phrase is a clear case of Chinglish as poor translation.

Defining Chinese English

Wei & Fei (Reference Wei and Fei2003) group the terms Chinese English and China English together, suggesting that ‘Chinese English has tended to be held in contempt by both native speakers and most Chinese’ (p. 44), whereas China English is a more widely-accepted title for the developing variety of English that is now being spoken in China. Similarly, Hu (Reference Hu and Chen2006) says that there is ‘no clear distinction between the terms’ Chinese English and Chinglish and describes them as being ‘at the opposite ends of a continuum’ (p. 231). I propose that it is dangerous to group together these two forms of English, because there are clear differences between the interlanguage spoken by Chinese learners of English (what I term Chinese English) and the maturing cultural variety of English that is developing, outlined later in this paper as China English.

Aspects of Chinese English

If we take Richards et al.'s (Reference Richards1992) definition of interlanguage, we can see that it is:

the type of language produced by second- and foreign-language learners who are in the process of learning a language. In language learning, learner's errors are caused by several different processes. These include:

a. borrowing patterns from the mother tongue

b. extending patterns from the target language.

c. Expressing meanings using the words and grammar which are already known (p. 186)

If we look at Chinese English as an interlanguage, the descriptive rules of English at work are obvious, though not always in a ‘native-like’ fashion. Often, Chinese English is the product of errors made by learners as they advance in fluency level. Chinese syntax or sentence structure with English words might be used, or at other times erroneous but intelligible uses of grammatical patterns (e.g. wrong past tenses, present progressive, etc), erroneous word choice, or the wrong application of rule structures. These forms of interlanguage do not constitute a new variety in and of themselves, but are usually still understandable to native speakers despite the errors. According to Wei and Fei, ‘Individual learners, in using English, translate more or less from Chinese and tend to ignore the basic grammatical structure of English’ (2003, p. 43). In this way, Chinese English as an interlanguage may not differ significantly from the interlanguages used by other learners of English around the world. Example A is an excerpt from a transliterated version of a speech given by one of the author's Chinese secondary school students:

Example A: Chinese English

You bring us happy. Where have you where have happy.

The student first fails to transform ‘happy’ from its adjectival form to its nominal form, ‘happiness’. Though this does not render the sentence unintelligible, it is the product of an inexperienced speaker who will presumably learn its standard pattern with more practice. Furthermore, this pattern would be common and particular to Chinese English because, in Mandarin, adjectival and nominal forms are often the same (as in this case, where 高兴 (gāoxìng) means ‘happy’, ‘happiness’ and ‘to be happy’).

In the second sentence, the student literally translates an idiom from Mandarin using a combination of Chinese syntax and English words: 哪里有你 那里有高兴 (năli yŏu nĭ, nàli yŏu gāoxìng), which can be glossed as: ‘where have you, there have happy’. It should be noted that the student incorrectly translates a second ‘where’ which should actually have been ‘there’. This is an easy error to make, as the words for ‘there’ and ‘where’ in Mandarin are homophonic except for their tones: 哪里năli – 3rd tone = where; 那里nàli – 4th tone = there. Example B, taken from a second student's speech, demonstrates improper word choice as a component of Chinese English.

Example B: Chinese English

But this year, I know, in the future, if you don't speak English, you can't find a good work. So now I study English very carefully, and I want everyone can help me.

In the first sentence, she uses the word ‘work’ (a verb) where the word ‘job’ (a noun) would be standard. Like gāoxìng in the previous example, here ‘work’ and ‘job’ are synonymous in the Mandarin word 工作 (gōngzuò) which carries both the verbal and nominal meanings. In the second sentence, she says ‘I want everyone can help me’, where the standard pattern would be ‘to’ instead of ‘can’ in the use of the infinitive ‘to help’. Here, she uses a Chinese verb construction where a lack of verb conjugation in Mandarin means that it is entirely possible to place two verbs next to one another in a sentence. In Standard English, however, only conjugated and infinitive verb forms may be used side-by-side. Furthermore, her choice of the word ‘can’ reflects the Mandarin use of the word 会 (huì), which means both ability and permission to do something.

Figure 4 was photographed at a civic museum in Zhejiang Province. It shows a very clear example of misapplied grammatical rules.

Figure 4. Chinese English

The translator obviously meant ‘No photographing’ or ‘No photography’, but instead used the same conjugational pattern as in ‘No smoking’ (where the final ‘e’ is dropped from ‘smoke’ and the suffix ‘ing’ is added) and misapplied it to the word ‘photo’ rendering the phrase unintelligible. When viewed in context to its partner sign, this becomes an obvious case of interlanguage, where a learner is not yet fluent in the appropriate use of grammar patterns. It would be out of place to label this as China English because the example is an obvious result of misuse rather than a developing new trend in language function.

Figure 5 is a similar final example of Chinese English as an interlanguage.

Figure 5. Chinese English

In this case, the translator obviously meant ‘recyclable’ and ‘non-recyclable’ with the phrases ‘can't reusing’ and ‘can reusing’. Two things have happened in this case. First examining the nature of the Mandarin structure, 不可回收 (bù kĕ huìshōu) and 可回收 (kĕ huìshōu) can be glossed as ‘cannot recycle’ and ‘can recycle’ (from left to right in the photo), making clear why the initial structure of ‘can't’ and ‘can’ was used. However, a second pattern has occurred in the employment of the present progressive form ‘reusing’. While it is obvious that ‘reuse’ is a suitable synonym for ‘recycle’, it is impossible to explain why the present progressive verb form was chosen. Nonetheless, here again it is not a new developing pattern of English but simply a misapplied grammar structure that, presumably, would not occur if the translator was more experienced using English.

Again, these fundamental mistakes do not render the sentences entirely unintelligible to a native speaker, but they are obviously errors resulting from the speaker's lack of practice using English rather than new patterns developing in a China variety of English. Since the phrases are clear despite the misused patterns, they cannot be defined as Chinglish. As well, the patterns are not necessarily new developing forms of English particular to China, so they cannot be called China English, as will be described in the third section below. They fall into this intermediary category of an interlanguage – Chinese English.

Defining China English

The term China English has, by now, been well defined by linguists over the past 20 years. One of the most quoted writers on this particular topic is Li Wenzhong, whose definition has been used by dozens of succeeding researchers. Kirkpatrick and Xu (Reference Kirkpatrick and Xu2002) quote Li's definition of China English:

China English is based on a standard English, expresses Chinese culture, has Chinese characteristics in lexis, sentence structure and discourse but does not show any L1 interference. (p. 269)

The meaning of ‘L1 interference’ here is the type of grammatical misuse we have seen occurring in Chinese English, defined in this essay as an interlanguage. So, Li distinguishes between Chinese English, with L1 interference, where the language learner uses certain aspects of her native language (L1) when trying to speak a second language (L2), and China English, which he terms a developing new variety with its own lexicon, structure, and discourse. According to Xu, as quoted in Poon (Reference Poon2006), there are at least four major features of China English: varied pronunciation and accent, particular lexical items, an idiosyncratic syntax, and distinct discourse varieties (p. 24). Wei and Fei (Reference Wei and Fei2003) also list several excellent examples of these four aspects of China English, including specific aspects of China English syntax and discourse.

Pronunciation and accent

Though a detailed analysis of the phonology of China English is outside the scope of this essay, a few examples will be provided here.

/θ/ → /s/ Speakers of China English often substitute /s/ where a Standard English speaker would use /θ/. This is because Mandarin has no sound equivalent to the English /θ/, an unvoiced dental fricative, so speakers choose the next closest linguistic component available to them, an unvoiced alveolar fricative, as a substitute. /ð/ → /z/ or /ð/ → /d/ Similarly, the voiced dental fricative /ð/ changes to voiced alveolars, which are the closest phonemes available in Mandarin. Finally, because Mandarin is a monosyllabic, tonal language, there is a tendency for China English speakers to use a very staccato style of speaking, where an additional /ə/ is sometimes added on to the end of a morpheme or lexical item to make it more readily pronounceable. For example, the Standard English /kæt/ may change to /kætə/ in China English. As well, the tonal nature of Mandarin results in China English speakers ‘adding’ tones to English words where they do not exist, or changing the stressing of syllables.

Lexical items

As Jian Yang (Reference Yang2005) points out, ‘borrowing has long been recognized as an important part of the nativization that English has undergone’ (p. 425). To accurately talk about borrowings, it would be useful to define several terms, as there have been many arguments on the various expressions used regarding this subject. Though many definitions have been put forward, I will use Suzanne Romaine's (1995) definitions, as follows:

• loanblend – one part of a word is borrowed and the other belongs to the original language.

• loanshift – taking a word in the base language and extending its meaning so that it corresponds to that of a word in the other language.

• loan translation – rearranging words in the base language along a pattern provided by the other and thus creating a new meaning. (Romaine, Reference Romaine1995: 56–7)

Lexical innovations in China English mostly fall into one of these three categories, but to stay within scope here, I will only give some examples rather than provide lengthy discussions of how each example should be sorted according to the above categories.

In short, China English lexical items are words that can be easily recognised as English; however, they generally express ideas or things specific to Chinese culture and are therefore useless or even meaningless in the context of standard, native, or international Englishes. Distinctive examples of China English lexical items include such terms as autonomous region, colour wolf, dragon boat, little red cap, Mid-Autumn festival, one country two systems, red envelope, and special administrative region.

Although these words and phrases can easily be identified as English, their meaning is often inaccessible to English speakers outside China. For instance, the phrase colour wolf is a direct loan translation from Mandarin, roughly equivalent to ‘sex maniac’. And, although a speaker of other varieties of English would easily be able to visualise a red envelope in its literal sense, within the Chinese cultural context, the phrase refers to a special monetary gift, often given at Chinese New Year or to exchange favours. So, these lexical items are very clearly Chinese in context and culture, and not fully comprehensible to users of English outside the Chinese context.

Syntax

Wei and Fei (Reference Wei and Fei2003) provide a lengthy discussion of China English syntax with examples of six features of variation, including (i) word order differences, (ii) open head vs. open end, (iii) time sequence, (iv) compound and complex sentence structures, (v) special subjects and (vi) the use of the passive voice (pp. 44–5). Let us take as an example feature (ii), open head vs. open end, where, in China English, subordinate clauses are often put in front of main clauses. Example C is taken from a personal email to the author.

Example C: China English grammar (1)

As I am currently in China with an ABQ delegation doing projects of business, medical consulting, fashion-textile design, and Chinese investment to the US, I could not come myself.

In Standard written English, this might be phrased:

I could not come myself, as I am currently in China with an ABQ delegation doing projects […]

following the pattern main clause + subordinate clause. Kirkpatrick and Xu (Reference Kirkpatrick and Xu2002) point out that this phenomenon often occurs with ‘because’ as a forward pointing discourse marker at the beginning of a sentence. Example D shows this in another personal email.

Example D: China English grammar (2)

Because he can not reply you in time, I contact you directly. I hope my English won't let you down.

Though this may cause confusion for a native speaker for whom ‘because’ is a signifier that important information has already been transmitted, for China English speakers, ‘because’ is often placed first in a sentence in the Chinese language, and this structure is often transferred into English.

Discourse

Far less research has been done with regard to the discourse patterns of China English, although Kirkpatrick and Xu (Reference Kirkpatrick and Xu2002) point out a striking feature of written discourse patterns in China English, where ‘facework’ plays an important role:

The first half of the letter is taken up with what Scollon and Scollon (1991) have called ‘facework’. Then the writer introduces the reasons for a particular request and then, finally, makes the actual request. We could simplify the schema to: Salutation, Facework, Reason/Justification, Request, Sign off. (p. 274)

With this pattern in mind, let us examine Example E, a personal email to the author of this article:

Example E: Discourse features of China English

Salutation: Hello …

Facework: I am [author] (I am Chinese), the colleague of [name] (our foreign advisor). Because he can not reply you in time, I contact you directly. I hope my English won't let you down.

Reason/Justification: It was a long time since my last mail. We are so glad to hear the news that you agree to write for us. Your experience and story is very valuable for our website and tourists. We are hoping to get your story as soon as possible. We will pay you due the time we got the stroy. [sic] So don't worry about that. We have been in business since 1998 and enjoy high reputation home and abroad. I appreciate your writing style and creative idea. It is a happy experience to write to you.

Request: So could you tell me how many stories do you have in hand or be going to write? What price do you charge for your story? When can you finish your story and send it or them to us?

Sign off: I am looking forward to your reply!

Best wishes,

Author

As we can see, this email clearly follows the pattern described in Kirkpatrick and Xu. First, the author introduces himself with a salutation. Next, he engages in facework, whereby he creates ‘good face’ by complimenting the recipient and noting his connection to her via a third party. Third, he shows his reason and justification for writing while still employing further facework in phrases like ‘Your experience and story is very valuable.’ Finally, he signs off by asking for a reply and sending best wishes. This type of discourse pattern is very particular to users of China English, especially in the Chinese cultural context where face represents a critical social concept. So, it makes sense that the breadth of the communication is taken up by discourse efforts toward positive facework and justification, whereas the same letter in Standard English would display the request with far less concern for them. China English is unique across the linguistic spectrum, from phonology to discourse. In the light of Butler's five criteria for nativisation, it is obviously still a developing variety, but the aspects shown above suggest that China English is on its way to becoming an established variety of English.

Conclusion

This essay has examined three types of English that exist in Mainland China, distinguishing particularly between Chinglish and Chinese English, which have been grouped together by previous linguists. Chinglish can be viewed as an erroneous form of language that is the result of poor translation, and it generally only exists in written form. Chinese English is an interlanguage used by Mandarin-speaking English learners in China. It is easily understood as being English by Inner Circle speakers, but it often contains so-called L1 interference, or Mandarin structural features. Misplaced or errantly used grammatical patterns are another characteristic of Chinese English. Finally, China English is a developing world variety of English. It has unique features including phonology, lexicon, syntax, and discourse patterns, and therefore it fulfils three out of Butler's five criteria toward becoming a nativised variety. As China develops socially and opens economically over the next decade, the use of English there will only be widened and further refined into an established Expanding Circle World English.

MEGAN EAVES holds an MA in Intercultural Studies from Dublin City University in Ireland and a BA in Intercultural Communication and Mandarin Chinese from the University of New Mexico. Her primary research interests include intercultural communication, cross-cultural adaptation, China English, Chinese culture and Irish culture. In addition to being a qualified intercultural trainer, she has spent several periods of time living in China, learning and studying the local speech patterns and has taught English in several Chinese middle and secondary schools. She is the author of numerous publications, including This Is China: A Guidebook for Teachers, Backpackers and Other Lunatics (Lulu, 2009). Email: [email protected]

MEGAN EAVES holds an MA in Intercultural Studies from Dublin City University in Ireland and a BA in Intercultural Communication and Mandarin Chinese from the University of New Mexico. Her primary research interests include intercultural communication, cross-cultural adaptation, China English, Chinese culture and Irish culture. In addition to being a qualified intercultural trainer, she has spent several periods of time living in China, learning and studying the local speech patterns and has taught English in several Chinese middle and secondary schools. She is the author of numerous publications, including This Is China: A Guidebook for Teachers, Backpackers and Other Lunatics (Lulu, 2009). Email: [email protected]