Introduction

Much more timely differentiation of major depressive (MDD), bipolar-1 (BD-1), and bipolar-2 (BD-2) disorders is clinically crucial to improving long-term planning aimed at better care of mood disorder patients [Reference Serra, Koukopoulos, De Chiara, Napoletano, Koukopoulos and Curto1]. Notably, the latency from initial clinical manifestations to a firm diagnosis and appropriate treatment of BD as distinct from unipolar depression averages 5–10 years, and even longer with onset in juvenile years, owing in large part to an excess of depression early in the course of BD [Reference Baethge, Tondo, Bratti, Bschor, Bauer and Viguera2,Reference Baldessarini, Tondo, Baethge, Lepri and Bratti3]. In striking contrast, nearly half of lifetime risk of suicidal acts (attempts and suicides) occurs within the first 2–3 years of these illnesses, and indeed such acts make early diagnosis more likely [Reference Tondo, Baldessarini, Hennen, Floris, Silvetti and Tohen4]. The uncertain differentiation of BD from MDD is underscored by the finding that more than half of patients originally diagnosed with a depressive episode eventually meet diagnostic criteria for BD, often owing to missing diagnosis of BD-2 through failure to recognize hypomania [Reference Angst, Sellaro, Stassen and Gamma5]. In addition, prolonged duration of untreated illness in BD is associated with more suicide attempts, greater affective and behavioral instability, and possibly more prolonged future illness [Reference Altamura, Dell’Osso, Berlin, Buoli, Bassetti and Mundo6,Reference Drancourt, Etain, Lajnef, Henry, Raust and Cochet7].

A potential contribution to improving early recognition of BD and MDD might include use of ratings of affective temperament or assessment of other aspects of temperament and personality, seeking potential links between a biological disposition to mood disorder and its clinical manifestations and considering some temperaments as antecedents of particular mood disorders [Reference Gonda, Fountoulakis, Juhasz, Rihmer, Lazary and Laszik8,Reference Gonda, Eszlari, Torok, Gal, Bokor and Millinghoffer9]. Such assessments often rely on questionnaire-based rating schemes, including the Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris, and San Diego (TEMPS, often as a self- or auto-rating, TEMPS-A) [Reference Akiskal, Akiskal, Hayakal, Manning and Connor10], the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) [Reference Cloninger, Svrakic and Przybeck11], and the Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness Scale (NEO-PI-3) [Reference McCrae, Costa and Martin12]. In addition to supporting earlier, accurate diagnosis, such assessments might also have predictive value for the types and relative amounts of particular psychopathological features [Reference Fountoulakis, Gonda, Koufaki, Hyphantis and Cloninger13], and temperaments have shown strong relationships with suicidal behavior or ideation [Reference Vázquez, Gonda, Lolich, Tondo and Baldessarini14].

Several studies have focused on temperament assessments in individuals diagnosed with MDD [Reference Maina, Salvi, Rosso and Bogetto15–Reference Gurpegui, Ortuño and Gurpegui17] or with BD specifically [Reference Perugi, Toni, Maremmani, Tusini, Ramacciotti and Madia18–Reference Fico, Caivano, Zinno, Carfagno, Steardo and Sampogna24], or have considered mood disorders together using TCI [Reference Zaninotto, Souery, Calati, Di Nicola, Montgomery and Kasper25,Reference Balestri, Porcelli, Souery, Kasper, Dikeos and Ferentinos26] or TEMPS [Reference Serra, Koukopoulos, De Chiara, Napoletano, Koukopoulos and Curto1,Reference Aguiar Ferreira, Vasconcelos, Neves, Laks and Correa27–Reference Morishita, Kameyama, Toda, Masuya, Fujimura and Higashi30]. Such studies have revealed differences between mood disorder patients and controls, including unaffected family members, with suggestive differences between BD and MDD patients and possibly between BD-1 and BD-2 patients based on ratings of cyclothymic, hyperthymic, and irritable temperaments, in particular, as well as ratings of harm-avoidance [Reference Serra, Koukopoulos, De Chiara, Napoletano, Koukopoulos and Curto1,Reference Loftus, Garno, Jaeger and Malhotra31–Reference Zaninotto, Solmi, Toffanin, Veronese, Cloninger and Correll33]. There are also preliminary suggestions that temperament assessments may help to predict responses to antidepressant or mood-stabilizing treatments [Reference Aguiar Ferreira, Vasconcelos, Neves and Correa28].

However, most studies focusing on assessment of temperament in individuals with major mood disorders suffer from various limitations. These include small sample size, data not systematically analyzed by multivariate analyses, as well as retrospective or cross-sectional study designs that limit ability to form hypotheses regarding causality. In addition, it is important to consider potential effects of current mental state, which may influence responses to questions aimed at evaluating affective temperament [Reference Baba, Kohno, Inoue, Nakai, Toyomaki and Suzuki34]. Finally, relationships among affective temperament, morbidity indices, and clinical course in mood disorder patients have not been investigated extensively.

Given this background, the aim of the present study was to compare temperament profiles, assessed with the TEMPS-A questionnaire, in BD-1, BD-2 and MDD patient-subjects, and to test whether such assessments can contribute to differentiating among these diagnoses and can provide predictive associations with types or amounts of selected aspects of psychopathology.

Methods

Study subjects

Participants were adults evaluated and followed by the same mood disorder expert (LT) for several years at the Lucio Bini Mood Disorders Center in Cagliari, Sardinia, a specialized, academic outpatient clinic for the diagnosis, treatment, and study of affective disorder patients. They were consecutive and unselected except for adult age, presence of a DSM-5 major affective disorder (BD-1 or BD-2, MDD), and having completed TEMPS-A assessment. All were treated clinically and followed prospectively and systematically over several years. Written, informed consent was provided by all participants for collection and analysis of clinical data to be presented anonymously in aggregate form, following procedures approved by a local ethical review committee in accordance with requirements of Italian law and with the Helsinki Declaration. Study data were collected and entered a computerized database in coded form.

Measures

Current and lifetime diagnosis, course of illness, and psychiatric comorbidities were assessed according to DSM-5 diagnostic criteria [35]. TEMPS-A assessments were obtained following intake and initial treatment. Temperament was rated with the 39-item version of the self-rated TEMPS-A scale [Reference Akiskal, Mendlowicz, Jean-Louis, Rapaport, Kelsoe and Gillin36]. We considered raw, average numerical scores for five individual temperaments (cyclothymic [cyc], 12 items; dysthymic [dys], irritable [irr], hyperthymic [hyp], 8 items each; and anxious [anx], 3 items). Clinical measures were: diagnosis (BD-1, BD-2, MDD) score for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS21), any suicidality (ideation or acts), or suicidal acts, substance abuse, episodes/year, and %-time ill overall or in depression or [hypo]mania or total. For multivariate modeling, factors with preliminary bivariate differences were included stepwise as covariates.

Data analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation or with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Differences in TEMPS-A scores, sociodemographic factors, and morbidity indices were evaluated using contingency tables (χ 2) for categorical variables or analysis of variance (t-test) for continuous data, followed by post hoc comparisons, or with bivariate linear regression (r) to compare continuous measures. Statistics arising from preliminary bivariate comparisons were used to guide selection of factors to include in multivariable modeling, so as to limit effects of multiple comparisons. Statistics provided in tables are not repeated in the text. Analyses employed commercial software: Statview.5 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for spreadsheets, and Stata.13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for analyses.

Results

Subject characteristics

A total of 858 adults included: BD (n = 423), type 1 (n = 173) or 2 (n = 250), or MDD (n = 435). They were treated clinically and followed prospectively and systematically over an average of 7.99 [7.19–8.79] years. Age at intake averaged 46.2 [45.7–46.7] years; 62.9% [61.4–64.3] of subjects were women.

TEMPS-A subscores versus diagnosis

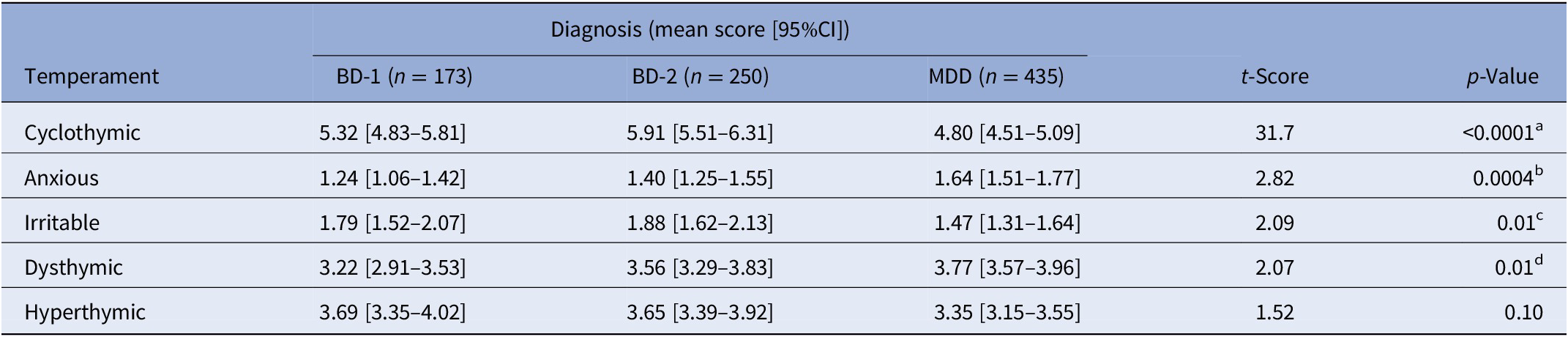

We compared scores for the five temperament types with three diagnoses (Table 1). Diagnostic subgroups differed highly significantly in TEMPS-A ratings of cyclothymic (cyc) and anxious (anx) temperament (p < 0.001 overall for both). The cyc ratings ranked among the diagnoses as: BD-2 > BD-1 > MDD; anx, ratings ranked: MDD > BD-2 > BD-1. Also significant were ratings for irritable temperament (irr) which ranked: BD-2 ≥ BD-1 > MDD and for dysthymic temperament scores (dys), ranking: MDD > BD-2 > BD-1 (p = 0.01 overall for both). Ratings of hyperthymia (hyp) did not differ significantly among the diagnoses (p = 0.10).

Table 1. TEMPS-A temperament scores versus diagnosis.

Note: Temperaments are ranked by significance of diagnostic differences. Significant (p ≤ 0.05) post hoc comparisons: aBD-2 > BD-1 > MDD; bMDD > BD-2 > BD-1; cBD-2 = BD-1 > MDD; dMDD > BD-2 > BD-1. Scores vary with the number of items for each temperament type (e.g., 12 for cyclothymic and 3 for anxious).

Abbreviations: BD-1, type I bipolar disorder; BD-2, type II bipolar disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder.

In addition, the ratio of individual scores for cyc/anx strongly differentiated BD (3.89 [3.55–4.23]) from MDD (2.70 [2.48–2.92]) patients (t = 5.94, p < 0.0001), whereas this ratio was very similar in BD-1 (3.83 [3.28–4.38]) and BD-2 (3.93 [3.50–4.36]) cases. The preceding findings suggest that high ratings for cyc and low scores for anx may help to differentiate BD from MDD, with additional contributions by high irr scores and low dys ratings also favoring BD over MDD.

Clinical features associated with temperament ratings

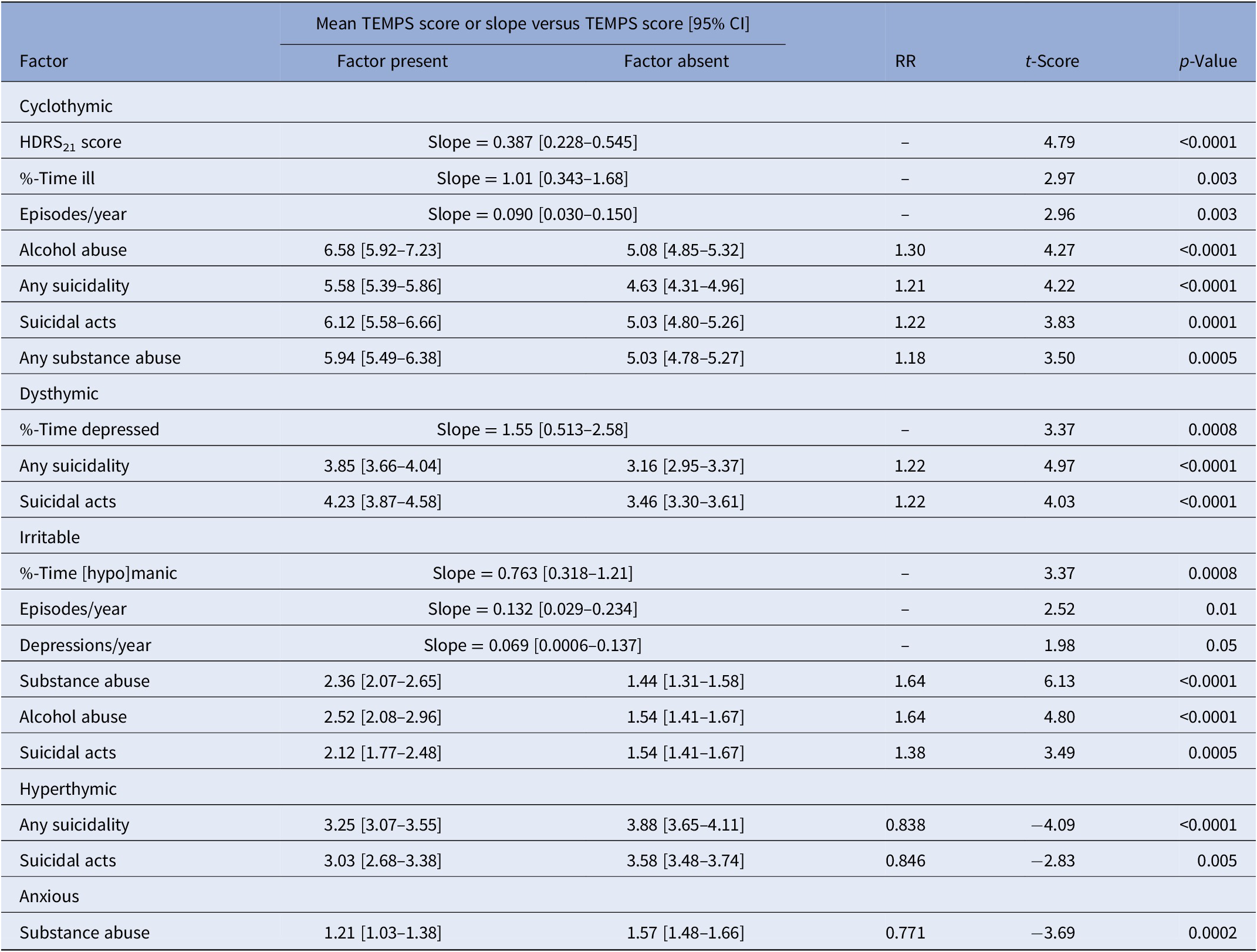

Among all 858 mood disorder participants, several clinically important features were associated with particular temperament ratings, irrespective of diagnosis (Table 2). Ratings of cyclothymic temperament (cyc) were strongly associated with: alcohol abuse and substance abuse of any kind, as well as suicidal ideation or acts and suicidal acts (attempts and suicides) specifically. These scores were also significantly correlated with higher depression ratings at intake (HDRS21), a greater proportion of time ill during several years of follow-up, and with a higher recurrence frequency (episodes/year).

Table 2. Clinical factors associated with TEMPS-A temperament assessment scores for 858 patients diagnosed with a DSM-5 major mood disorder.

Note: Clinical factors were assessed during an average of 7.99 [7.19–8.79] years of prospective follow-up. All morbidity indices assessed were: depressions, [hypo]manias, or total episodes per year; % time depressed, manic or total; HDRS21 score; any suicidality (acts + ideation), suicidal acts, substance abuse, and alcohol abuse.

Dysthymic temperament ratings (dys) were also highly significantly greater with both suicidal acts or any form of suicidality (including ideation and acts), and correlated strongly with higher percentage of time depressed.

Irritable temperament scores (irr) were highly significantly greater in patients with co-occurring abuse of any substances or of alcohol specifically, and with suicidal acts, and significantly correlated with more depressions/year, episodes/year, and especially with %-of-time during follow-up in mania or hypomania (“[hypo]mania”).

As expected [Reference Vázquez, Gonda, Lolich, Tondo and Baldessarini14], scores for hyperthymic temperament (hyp) were highly significantly lower (by 15–16%) in patients with a history of suicidal acts or with any suicidality (ideation or acts).

Ratings of anxious temperament (anx) were found to be significantly lower (by 23%) in patients with co-occurring substance abuse than among those without substance abuse (Table 2).

Diagnostic types associated with temperament ratings

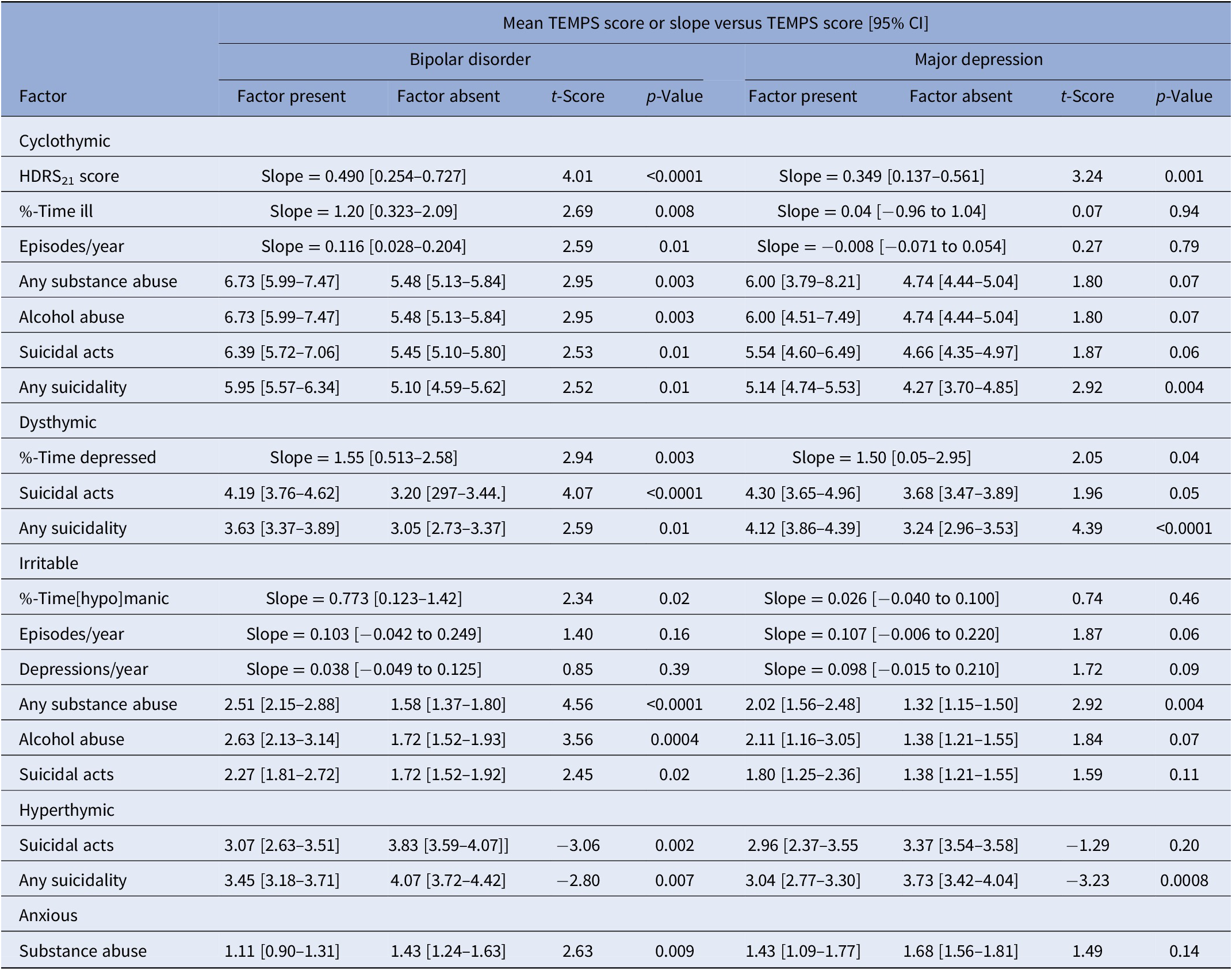

Some of the preceding findings among all mood disorder subjects were found selectively in BD or MDD, or occurred with both diagnoses (Table 3). Higher intake HDRS21 scores were strongly associated with higher scores for cyclothymic temperament (cyc) in both BD and MDD patients, as well as with any lifetime suicidal ideation or acts, but with suicidal acts only among BD patients. Other clinical factors also were associated with higher cyc scores selectively with BD but not MDD, notably including abuse of alcohol or of any substance, as well as %-time-ill and episodes/year.

Table 3. Clinical factors associated with TEMPS-A temperament assessment subscores with diagnoses of bipolar disorder versus major depressive disorder.

Ratings of dysthymic temperament (dys) were associated with %-time-depressed and with suicidal acts or any suicidality in both BD and MDD patients.

Ratings of irritable temperament (irr) were elevated with co-occurring substance abuse in both BD and MDD patients. However, the following factors were associated with higher irr scores only with BD: alcohol abuse specifically, suicidal acts, and %-time [hypo]manic, whereas depressions/year and mood episodes/year were not significantly associated with irr scores in either BD or MDD patients.

Hyperthymic temperament ratings (hyp) were selectively lower with suicidal acts only among BD, but not MDD patients. However, any suicidality, including suicidal ideation as well as suicidal acts, was associated with lower hyp scores in both diagnostic groups.

Lower ratings of anxious temperament (anx) were associated with substance abuse only among BD patients and not with MDD (Table 3).

Multivariable regression modeling

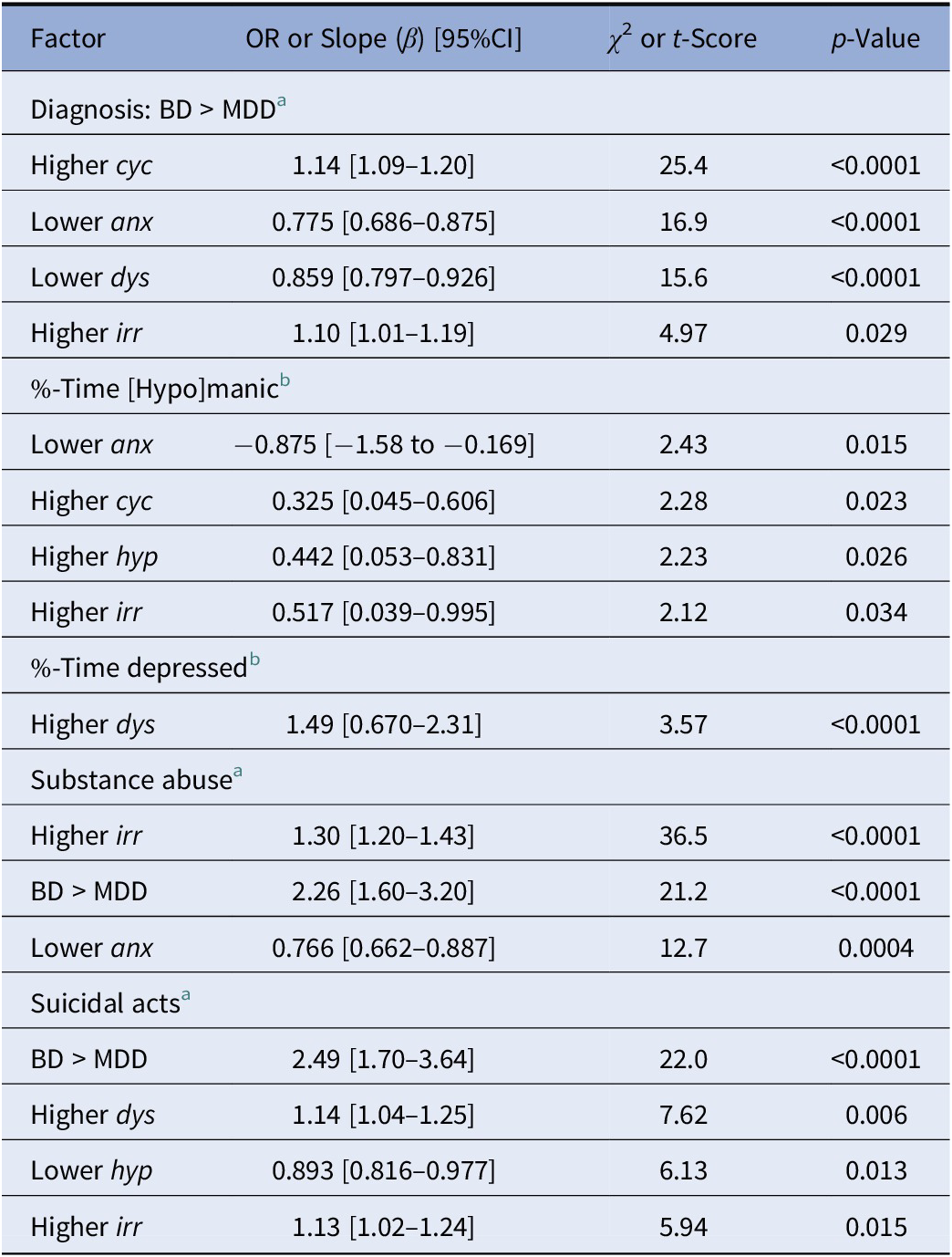

Based on the preliminary findings just summarized, we constructed multivariable logistic regression models for associations of temperament ratings with diagnosis (BD vs. MDD), substance abuse, and suicidal acts. In addition, we used linear regression models for %-time during prospective follow-up in [hypo]mania or depression (Table 4). Diagnosis of BD was more likely than MDD with increased ratings for cyc, lower scores for anx and dys, and lower ratings for irr. In addition, a particularly strong differentiating factor was the ratio of cyc/anx ratings. In logistic regression modeling, along with lower dys and higher irr scores, the ratio of cyc/anx scores separated BD from MDD very strongly (OR = 1.22 [1.14–1.32], χ 2 = 28.8, p < 0.0001). The proportion of time in [hypo]mania was associated with decreased anx, and increased cyc, hyp, and irr scores. In contrast, the %-time in depression was strongly and selectively associated only with higher dys scores. Substance abuse was associated strongly with increased irr scores, lower anx scores, and with BD more than MDD. Finally, suicidal acts (attempts and suicides) were strongly associated with BD > MDD and with higher dys ratings, and less strongly with increased irr and lower hyp scores (Table 4).

Table 4. Multivariable models for clinical outcomes.

Note: Lower hyp scores with suicidal acts or ideation were found in preliminary bivariate analyses with both BD and MDD subjects, but selectively with BD for suicidal acts (Table 3 ).

Abbreviations: anx, anxious temperament; BD, bipolar disorder; cyc, cyclothymic temperament; dys, dysthymic temperament; hyp, hyperthymic temperament; irr, irritable temperament; MDD, major depressive disorder.

a Logistic regression modeling (OR).

b Linear regression modeling (slope).

Discussion

This study involved data collected longitudinally for an average of 7.99 years of prospective observations of 858 unselected, consecutive individuals (a total of 6,855 person-years). We aimed to compare ratings of affective temperaments in patients diagnosed with a DSM-5 major affective disorder. We found several relationships of clinical interest that differentiated individuals with BD versus MDD and provided predictive associations with other clinical features of interest (Tables 3 and 4). This appears to be the first such study with a large sample size and longitudinal design aimed at evaluating the predictive value of affective temperament ratings with diagnostic and morbidity measures in patients diagnosed reliably with DSM-5 BD-1, BD-2, or MDD.

Multivariable logistic regression modeling revealed that higher scores for cyclothymic and irritable temperaments were independently more likely among BD than MDD patients, whereas dysthymic and anxious temperament scores were higher in MDD than BD (Table 4). Moreover, the ratio of relatively high ratings for cyclothymic and low scores for anxious temperament was especially elevated with BD and distinguished BD from MDD.

Such results are consistent with previous studies comparing affective temperaments in patients with major mood disorders, in which BD cases showed higher cyclothymic and hyperthymic and lower anxious temperament scores than did MDD cases [Reference Aguiar Ferreira, Vasconcelos, Neves, Laks and Correa27]. In addition, cyclothymic and hyperthymic temperament ratings have been reported to be BD-selective [Reference Serra, Koukopoulos, De Chiara, Napoletano, Koukopoulos and Curto1]. We also found a preliminary association of BD diagnosis with elevated hyperthymia ratings (Table 1) that was not sustained in multivariable modeling (Table 4). Also of interest, relatives of BD patients have been reported to have higher cyclothymia scores than family members of MDD cases or healthy controls [Reference Aguiar Ferreira, Vasconcelos, Neves, Laks and Correa27].

Consistent with our findings, Morishita et al. [Reference Morishita, Kameyama, Toda, Masuya, Ichiki and Kusumi29,Reference Morishita, Kameyama, Toda, Masuya, Fujimura and Higashi30] found that cyclothymic and anxious temperament scores significantly differentiated the diagnosis of BD from MDD and statistically associated with BD by using multivariable logistic regression modeling. However, those studies also found that higher hyperthymic temperament scores differentiated subjects diagnosed with BD-1 versus BD-2, which we did not find (Table 1). The studies by Morishita et al. [Reference Morishita, Kameyama, Toda, Masuya, Ichiki and Kusumi29,Reference Morishita, Kameyama, Toda, Masuya, Fujimura and Higashi30] were based on a cross-sectional design and so may have missed some patients considered to have MDD who might later have met diagnostic criteria for BD [Reference Angst, Sellaro, Stassen and Gamma5,Reference Dudek, Siwek, Zielińska, Jaeschke and Rybakowski37,Reference Kim, Kim, Kim, Yang, Rhee and Park38]. Moreover, not all of their patients were currently in remission or euthymic, and some responses to temperament categorizing questions may have been influenced by current mood states [Reference Baba, Kohno, Inoue, Nakai, Toyomaki and Suzuki34,Reference Morvan, Tibaoui, Bourdel, Lôo, Akiskal and Akiskal39].

Our findings confirmed associations of suicidal risk with higher scores of all temperament types except for hyperthymic, which were lower (Tables 3 and 4), as had been noted previously [Reference Vázquez, Gonda, Lolich, Tondo and Baldessarini14,Reference Pompili, Baldessarini, Innamorati, Vázquez, Rihmer and Gonda40,Reference Tondo, Vázquez, Sani, Pinna and Baldessarini41]. We also found that higher cyclothymic and irritable scores and lower anxious scores were associated with substance abuse. Though few previous studies focused on the temperament profile in BD patients with abuse of alcohol or other substances, in line with our findings (Table 3), cyclothymic or irritable temperament was reported to be associated with substance abuse (especially among BD patients) [Reference DeGeorge, Walsh, Barrantes-Vidal and Kwapil42]. Low scores of anxious with high scores of irritable may reflect impulsivity commonly present with substance abuse. In addition, hyperthymia was associated with more severe hypomanic symptoms in multivariable modeling (Table 4), and in a previous study of 112 young adults at-risk for BD [Reference DeGeorge, Walsh, Barrantes-Vidal and Kwapil42]. Cyclothymic and hyperthymic traits preceded abuse of stimulants by years, based on evaluating longitudinal progression of the dual pathology in a small sample of BD patients [Reference Camacho and Akiskal43]. Among 1420 BD patients, several TEMPS-A scores were higher with alcohol abuse, particularly irritable and hyperthymic ratings, adjusted for potential confounders [Reference Singh, Forty, di Florio, Gordon-Smith, Jones and Craddock19]. Finally, regression modeling based on 1,090 BD patients found abuse of alcohol and of other substances to be associated with irritable and hyperthymic temperaments, especially in males [Reference Azorin, Perret, Fakra, Tassy, Simon and Adida21], whereas we found elevated scores of cyclothymic and irritable to be selectively associated with abuse of alcohol (Table 2).

We also found that several TEMPS-A scores were higher with measures of greater affective morbidity. In particular, higher ratings for dysthymia correlated strongly with the proportion of time in depression with both BD and MDD patients, whereas higher irritable ratings significantly correlated with more episodes/year and depressions/year, as well as with the proportion of time of BD subjects in mania or hypomania (“[hypo]mania”; Table 2). Finally, in addition to a strong association between cyclothymic temperament and initial depression severity assessed by HDRS21 (Table 2) in both MDD and BD subjects (Table 3), higher cyclothymia scores correlated significantly with %-time-ill and episodes/year but selectively only among BD subjects (Table 3).

High cyclothymia scores seem to be associated with relatively unfavorable prognosis, perhaps as reflecting emotional and behavioral instability. This view is consistent with previous studies’ finding that cyclothymic temperament can affect illness-course adversely [Reference Mechri, Kerkeni, Touati, Bacha and Gassab44–Reference Innamorati, Rihmer, Akiskal, Gonda, Erbuto and Belvederi Murri46].

Consistent with cyclothymic tendencies, mood reactivity and emotional dysregulation represent core psychopathological dimensions that often develop early in childhood [Reference Perugi, Hantouche and Vannucchi47]. BD patients, including those with cyclothymic temperament, are often initially misdiagnosed, typically as having MDD, potentially resulting in prolonged delay of appropriate treatment, higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity, and more histrionic, passive–aggressive, and less obsessive–compulsive personality types compared to those affected by BD without cyclothymic temperament—all probably tending to limit chances of attaining clinical remission [Reference Perugi, Hantouche and Vannucchi47,Reference Akiskal, Hantouche and Allilaire48].

In a sample of 51 remitted BD subjects followed for 24 months, cyclothymic temperament scores were associated with greater overall functional impairment, including home management, and both individual and social leisure activities [Reference Nilsson, Straarup, Jørgensen and Licht45]. In line with the present study, with respect to BD patients (Table 3), high cyclothymia ratings have been reported to predict an excess of affective recurrences even when controlling for medication nonadherence [Reference Nilsson, Straarup, Jørgensen and Licht45]. Finally, cyclothymic temperament in BD patients has been associated with inferior treatment adherence and inferior response to medication [Reference Buturak, Emel and Koçak20,Reference Fornaro, De Berardis, Iasevoli, Pistorio, D’Angelo and Mungo49] as well as to psychoeducation [Reference Reinares, Pacchiarotti, Solé, García-Estela, Rosa and Bonnín50].

Limitations

Some individuals may not have been fully euthymic, as their TEMPS-A assessments occurred early in their clinical assessment, soon after clinic entry, but none was acutely ill. Efforts to limit effects of multiple comparisons include the recommendation to consider of particular interest initial bivariate comparisons yielding p-value of ≤0.01, and the limited statistics arising from multivariable modeling.

Conclusions

The present findings support the clinical value of rating affective temperament types, including to help differentiate BD from MDD diagnoses, limit risk of later changing diagnosis from MDD to BD, and to predict morbidity (mood states, recurrence rates, substance abuse, and suicidal risk), as well as highlighting the value of cyclothymic mood instability as a generally adverse prognostic indicator. The findings presented require replication and extension. Assessment of temperament is easily attained with the TEMPS-A scale, and should be considered as a component of routine evaluation of mood disorder patients, with possible particular value in the often difficult task of predicting a change of diagnosis from MDD to BD.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from L.T. Restrictions are applied, given confidentiality issues.

Acknowledgments

R.J.B. was supported by a grant from the Bruce J. Anderson Foundation and by the McLean Private Donors Psychiatry Research Fund, and L.T. was supported by a grant from the Aretaeus Foundation of Rome.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.M., M.P., L.T., R.J.B; Data curation: A.M., M.P., L.T.; Formal analysis: L.T., R.J.B; Investigation: L.T.; Methodology: A.M., M.P., L.T.; Writing—original draft: A.M., M.P., L.T., R.J.B; Writing—review and editing: L.T, R.J.B.

Conflicts of Interest

No author or immediate family member has financial relationships with commercial entities that might appear to represent potential conflicts of interest with the information presented.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.