Cultural policy is at the roots of some of the most violent and long-lasting contemporary civil wars. Restrictions on mother-tongue education, access to the media, display of symbols and public celebration of festivities can motivate distinct cultural groups to seek autonomy or even independence – sometimes by violent means (Gurr Reference Gurr2000; Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Sambanis Reference Sambanis2001; Stewart Reference Stewart2008). Persisting conflicts over culture can hamper conflict settlement (Kirschner Reference Kirschner2018; Ross Reference Ross2007). Conversely, initiatives to promote mutual understanding and integration in the cultural realms are often deemed to help the resolution of violent conflicts (de Rivera Reference de Rivera2009; Ramírez-Barat and Duthie Reference Ramírez-Barat and Duthie2015).

In this study we explore whether including cultural reforms in a peace accord facilitates its success, and we build a theory on the relationship between different approaches to cultural reform, the core grievances at the heart of conflict and the success of a pact. We see peace processes as including cultural reforms when they explicitly map the reform of cultural institutions, defined as institutions engaging in the protection, reproduction or dissemination of aspects of culture (education, symbols, the media, museums, cultural activities, sport and cultural associations). While the existing literature explores the relative benefits of specific cultural reforms in a selected numbers of in-depth case studies (de Rivera Reference de Rivera2009; McGlynn et al. Reference McGlynn, Niens, Cairns and Hewstone2004; Ramírez-Barat and Duthie Reference Ramírez-Barat and Duthie2015), to our knowledge this is the first attempt to test these competing arguments on a large comparative scale.

Our theoretical framework identifies one key factor that determines the impact of cultural reforms on a peace process: the approach to cultural reform, on a spectrum between accommodationist and integrationist initiatives. The accommodationist approach encompasses reforms that ‘seek to ensure that each group has the public space necessary for it to express its identity’ (McGarry et al. Reference McGarry, O'Leary, Simeon and Choudhury2010: 41–42). The integrationist approach denotes reforms which ‘respond to diversity through institutions that transcend, crosscut and minimise differences’ (McGarry et al. Reference McGarry, O'Leary, Simeon and Choudhury2010: 41–42). Embedding accommodationist cultural policies in a peace accord firmly symbolizes the recognition of the formerly warring groups in the fabric of the state (King and Samii Reference King and Samii2018) and is deemed to be especially beneficial to managing confrontations between ascriptive groups, as in separatist conflicts (Gurr Reference Gurr2000; Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Lake and Rothchild Reference Lake and Rothchild1996).

However, we suggest that focusing only on the reassuring effect of cultural provisions overlooks their reputational effect: the impact of cultural provisions on negotiating leaders' reputation as legitimate political representatives of their respective conflict groups. We argue that accommodationist cultural reforms enhance this reputation. We therefore predict that, regardless of the grievances at the heart of conflict, the embedding of accommodationist cultural reforms into a peace accord facilitates its success in the short and medium term. This is because accommodation of the symbols and cultural markers of previously warring groups in a peace accord gives leaders crucial symbolic resources to consolidate their legitimacy, and consequently their control over their rank and file (Clements Reference Clements2014; McGarry et al. Reference McGarry, O'Leary, Simeon and Choudhury2010). Leadership challenges, rebel fragmentation and remobilization are key predictors of violence after the conclusion of peace accords (Rudloff and Findley Reference Rudloff and Findley2016). Therefore, enhanced reputation as legitimate representatives of group grievances (including the advantages warranted by the accommodation of group identities in the cultural institutions of the state) would result in a reduction in battle-related deaths in the medium and long term (Arnault Reference Arnault2014; Ramsbotham and Wennman Reference Ramsbotham and Wennmann2014). By the same logic, integrationist cultural reforms would problematize leaders' ability to both commit to pacts and ensure compliance among their rank and file, leading to the remobilization of conflict groups and renewed violence after the signing of a peace accord (Kirschner Reference Kirschner2018).

Complex patterns are evaluated most effectively through multimethod research designs (Beach Reference Beach2019). Thus, we employ the statistical analysis of a new, uniquely fine-grained data set to provide the first empirical test for our theoretical predictions. Our data set captures cultural reforms in all substantial intra-state peace agreements concluded between 1989 and 2017 (Fontana et al. Reference Fontana, Kartsonaki, Neudorfer, Walsh, Wolff and Yakinthou2020a, Reference Fontana, Siewert and Yakinthou2020b), complemented with an original coding of accommodationist and integrationist approaches to cultural reform. Through statistical analysis, we find that the inclusion of accommodationist cultural reforms in intra-state peace processes is significantly correlated with lower levels of post-agreement political violence across conflict types. Thus, our outcomes provide strong suggestive evidence that accommodation facilitates conflict management, regardless of the grievances at the heart of conflict, corroborating our argument on the reputational effect of accommodation. This is not to say that grievances are insignificant. Indeed, we find that integrationist cultural reforms have a particularly detrimental impact on separatist conflicts.

To illustrate our quantitative findings, we employ a case study well predicted by the statistical model (Beach Reference Beach2019; Lieberman Reference Lieberman2005): Northern Ireland's 1998 Good Friday Agreement (GFA). The GFA provides strong evidence that including accommodationist cultural provisions in a peace accord both reassures previously warring groups and protects the reputation of negotiating leaders as legitimate representatives of their group. Conversely, the inclusion of integrationist cultural provisions exacerbates commitment problems by undermining the reputation of negotiating leaders.

Our findings on the relationship between cultural reforms and successful peace agreements have important theoretical and practical implications. Peace processes typically mitigate commitment problems through the inclusion of provisions for power-sharing and third-party intervention. We suggest that the introduction of accommodationist cultural reforms may have equally powerful assuring effects, particularly where leaders' reputations are at stake. Moreover, an extensive literature underscores the beneficial impact of integrationist initiatives for long-term reconciliation and conflict resolution (de Rivera Reference de Rivera2009; Galtung Reference Galtung and Christie2011; McGlynn et al. Reference McGlynn, Niens, Cairns and Hewstone2004; Ramírez-Barat and Duthie Reference Ramírez-Barat and Duthie2015). We show that accommodationist cultural reforms may also contribute to the success of intra-state peace accords, particularly in separatist conflicts. In this light, accommodationist cultural reforms should be explored more thoroughly and exploited more systematically by scholars and policymakers interested in promoting conflict settlement.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. The next section presents our theoretical expectations in light of the literature on cultural reforms and war-to-peace transitions. We then present the quantitative analysis, where we model the relationship between cultural reforms and successful peace agreements using the negative binomial specification (as best practice in the presence of a count-dependent variable which is positively skewed). The following section focuses on the qualitative analysis of a well-predicted case for the purpose of illustrating our theory. Finally, we summarize our findings and highlight opportunities for further research.

Cultural reforms and the end of violence

In this study, we aim to understand the relationship between cultural reforms and the success of a peace agreement. While acknowledging that there is more to peace than the end of manifest violence (Galtung Reference Galtung and Christie2011; Mac Ginty Reference Mac Ginty2014), in this article we operationalize the success of peace accords with reference to the cumulative battle deaths in the five and ten years following the accord. Therefore, we focus on the relationship between the inclusion of cultural reforms in a peace agreement and post-conflict violence. We operationalize cultural reforms as peace accord clauses explicitly reforming cultural institutions, defined, as detailed above, as institutions engaging in the protection, reproduction or dissemination of aspects of culture (education, symbols, the media, museums, cultural activities, sport and cultural associations) (Fontana et al. Reference Fontana, Kartsonaki, Neudorfer, Walsh, Wolff and Yakinthou2020a). Cultural reforms are therefore distinct from more diffuse forms of cultural and ethnic recognition and from pledges for non-discrimination of cultural groups (cf. King and Samii Reference King and Samii2020).

There is broad agreement that reforms of cultural institutions can help conflict management. Cultural inequalities are crucial components of the horizontal inequalities which motivate intergroup grievances and underpin mobilization and violent conflict (Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Weidmann and Gleditsch2011; Gurr Reference Gurr2000, Reference Gurr2012; Kirschner Reference Kirschner2018; Østby Reference Østby2008; Stewart Reference Stewart2008). Moreover, cultural institutions remain a crucial site of socialization into collective social identities (Cramer Reference Cramer2003; Huddy Reference Huddy2001; Stewart Reference Stewart2008; Ukiwo Reference Ukiwo2007).

However, debate continues as to the most beneficial approach to cultural reforms, on the spectrum between accommodation and integration. In line with the conflict management literature, we distinguish between these two approaches to cultural reforms to evaluate their respective association with post-agreement violence. As described above, we define accommodationist cultural reforms as those which ‘promote dual or multiple public identities’ and ‘seek to ensure that each group has the public space necessary for it to express its identity’ (McGarry et al. Reference McGarry, O'Leary, Simeon and Choudhury2010: 41–42). Conversely, integrationist cultural reforms ‘respond to diversity through institutions that transcend, crosscut and minimise differences’ (McGarry et al. Reference McGarry, O'Leary, Simeon and Choudhury2010: 41–42).

Some scholars focus on the extent to which accommodationist provisions in peace accords enable commitment to a costly settlement by reassuring formerly warring groups of their future status in the state. The reassuring effect of accommodation is well established for identity-based conflicts, such as ethnic and separatist conflicts (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Lake and Rothchild Reference Lake and Rothchild1996), where recognition of multiple and conflicting identities through accommodationist constitutional provisions contributes to the resolution of ethnic conflicts (King and Samii Reference King and Samii2020). No large-scale cross-case analysis of the impact of accommodationist cultural provisions exists to date, but in-depth qualitative studies corroborate their reassuring effect. If ‘effective [conflict] management seeks to reassure minority groups of … their cultural security’ (Lake and Rothchild Reference Lake and Rothchild1996: 42), then it is reasonable to take at face value the public statements of minority representatives, suggesting that cultural reforms which recognize their diverse cultural expressions help nurture sustainable peace in separatist conflicts (Georgia Today 2018; Kelly Reference Kelly2018; Letsch Reference Letsch2017; Radonjic Reference Radonjic2007; Sheikho Reference Sheikho2018; UNIAN, 2018).

Our analysis is based on the idea that, in addition to their established reassuring effect, cultural reforms also have a powerful reputational effect across conflict types: that they impact on negotiating leaders' reputation as legitimate political representatives of their respective conflict groups. This perspective is grounded in the observation that conflict parties are not unitary actors (Cunningham Reference Cunningham2013; Driscoll Reference Driscoll2012; Lounsbery and Cook Reference Lounsbery and Cook2011; Prorok Reference Prorok2016; Rudloff and Findley Reference Rudloff and Findley2016) and their cohesion partly depends on leaders' legitimacy, meant as ‘the popular acceptance of [their] political authority’ (Ramsbotham and Wennmann Reference Ramsbotham and Wennmann2014: 6). Peace negotiations and the immediate post-conflict phase have been linked to increasing risks of factionalization and leadership challenges (Lounsbery and Cook Reference Lounsbery and Cook2011). In turn, factionalization exacerbates post-conflict uncertainty and increases the likelihood of a resumption of violence even after the conclusion of a peace accord (Cunningham Reference Cunningham2013; Lounsbery and Cook Reference Lounsbery and Cook2011; Rudloff and Findley Reference Rudloff and Findley2016). Thus, the conclusion and implementation of a peace accord is an act of coalition-building both across and within formerly warring groups (Driscoll Reference Driscoll2012). This act of coalition-building relies on, and in turn feeds into, leaders' legitimacy. In this phase, reputation will figure as a key consideration for negotiating leaders as it will affect their personal power (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Prorok Reference Prorok2016), the extent of group cohesion (Addison and Murshed Reference Addison and Murshed2002) and their ability to ensure compliance among their rank and file (King and Samii Reference King and Samii2018). Some literature suggests that accommodationist provisions further the reputation and legitimacy of negotiating elites immediately after a peace accord. However, no systematic large-scale study exists on the specific contents of peace accords which may help boost leaders' reputations as legitimate political representatives of their group's grievances, prevent factionalization and avoid post-conflict violence (Lounsbery and Cook Reference Lounsbery and Cook2011). We propose that the inclusion of cultural reforms in a peace accord can bring important reputational benefits across conflict types. In particular, the symbolic value of accommodationist cultural reforms would appeal to negotiating leaders in both separatist and governmental conflicts. This yields a first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The inclusion of at least one accommodationist cultural reform in a peace accord is associated with a reduction in post-conflict violence.

Other scholars suggest that accommodationist strategies for conflict management facilitate the violent mobilization of groups and the long-term exacerbation of conflict (Nagle Reference Nagle2014; Ross Reference Ross2007; Taylor Reference Taylor and Taylor2009). They propose that – regardless of the type of conflict – embedding ethno-cultural differences in the fabric of the state through, inter alia, accommodationist cultural provisions entrenches an ‘us versus them’ mentality and triggers a mobilization effect (King and Samii Reference King and Samii2018). Conversely, integrationist cultural reforms would erode intergroup differences, discourage group mobilization and prevent a return to violence (de Rivera Reference de Rivera2009; Ross Reference Ross2007). This argument contrasts with extensive qualitative evidence that, in separatist conflicts, measures revoking autonomy or seeking integration into overarching identities and narratives contribute to the resumption of violence (Kirschner Reference Kirschner2018; Walter Reference Walter2009). Our theory is that this is because integrationist cultural reforms have an adverse reputational effect, particularly where leaders' legitimacy is most closely tied to the expression of a distinct and separate cultural identity (as in separatist conflicts). We propose that by eroding leaders' reputation as legitimate representatives of their group, the inclusion of integrationist cultural reforms in a peace accord would contribute to a resumption of violence. This yields our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: The inclusion of at least one integrationist cultural reform in a peace accord is associated with an increase in post-conflict violence, particularly in separatist conflicts.

Quantitative analysis

In this article, we aim to detect and evaluate the potential contribution of the inclusion of cultural reforms to the end of violence in countries affected by civil conflict. This section focuses on our cross-case statistical analysis, which investigates the relationship between specific approaches to cultural reform and post-agreement violence worldwide.

Data

In our cross-case analysis, we employ novel, fine-grained data on cultural reforms in intra-state peace agreements based on the data set of Political Agreements in Internal Conflicts (hereafter, PAIC) (Fontana et al. Reference Fontana, Kartsonaki, Neudorfer, Walsh, Wolff and Yakinthou2020a).Footnote 1 The PAIC includes all substantial political agreements concluded globally between 1989 and 2016 and at present is the only extensive data set coding for reforms of cultural institutions. The PAIC also codes for provisions establishing power-sharing, territorial self-governance, third-party intervention, transitional justice, and for many contextual variables.Footnote 2 Therefore, the PAIC is uniquely well placed to address remaining questions about the relationship between the inclusion of cultural provision and the success of peace accords.

To reflect fine-grained differences in types of cultural reforms, we further coded cultural reforms into two categories – accommodationist and integrationist as defined above. An example of an accommodationist approach is evident in the GFA's clause on linguistic diversity (Agreement The 1998). Conversely, an integrationist approach underpins the GFA's commitment to integrated education (Agreement The 1998).

One fundamental concern arose regarding the population of peace agreements in the PAIC. While some conflicts were tackled by a single comprehensive political agreement (such as the GFA), others were addressed by as many as ten different agreements in 1989–2016 (as in the case of Guatemala's civil war). In the latter case, the agreements concluded to mitigate the same conflict have limited independence. We address these concerns by using robust standard errors clustered at the conflict level throughout the analysis. This allows for correlation between pacts that tackle the same conflict.Footnote 3 In addition, we run robustness tests to make sure that no agreement or set of agreements generated by a specific conflict disproportionately influences the analysis.

Measuring the conclusion of a successful peace agreement

We would expect a successful peace agreement to result in a robust and sustained decline in battle-related deaths. Therefore, to evaluate the success of a political agreement, we created a variable (cum_death_5) recording, for each conflict, the cumulative number of battle deaths in the five years following the year of its conclusion (following existing practice, for example Hartzell et al. Reference Hartzell, Hoddie and Rothchild2001). These data are based on the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) Battle-related Deaths Dataset (UCDP 2017). To get additional insights, we created a further variable (cum_death_10) recording the cumulative number of battle deaths in the ten years following a settlement. This allows us to estimate the success of the pact over a longer time frame than other existing studies (Hartzell and Hoddie Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2007).

Note that data on battle-related deaths are available for the period 1989–2017. This implies that for recent accords we are not able to calculate the exact cumulative number of battle deaths in the five (or ten) years following the agreement. In these cases (less than 15% of the total), we calculate the cumulative number of battle deaths in the available years and use this as an approximation for the dependent variable.Footnote 4

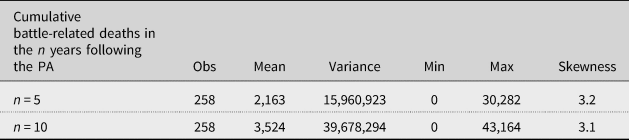

Table 1 reports some descriptive statistics on the cumulative number of battle-related deaths recorded in the five and ten years following each agreement.

Table 1. Battle-Related Deaths – Descriptive Statistics

Note: PA = peace agreement.

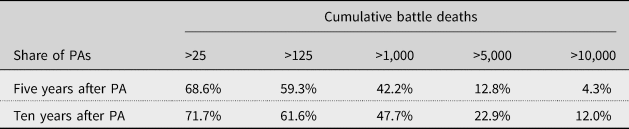

The high variances (as compared to means) suggest a situation of over-dispersion. In addition, it can be noticed that the distributions are positively skewed. This indicates that a few peace agreements display a very high number of post-agreement battle-related deaths. Table 2 shows the percentage of pacts which recorded less than a certain threshold of battle deaths (5, 25, 125, 1,000, 5,000, and 10,000) in the five and ten years following their conclusion.

Table 2. Distribution of Cumulative Battle Deaths in the Aftermath of Peace Agreements

Many peace agreements are not successful in driving battle deaths to zero. About 70% of peace agreements display a count greater than 25 in the five and ten years following the agreement conclusion. While in about 40% of cases the cumulative number of casualties in the five and ten years following the agreement is relatively low (below 125), in more than 40% of instances the level of violence remains high, with recorded deaths surpassing 1,000 units in the five and ten years after the agreement. This is in line with the existing literature, which estimates that up to 40% of civil wars recur within ten years of a peace accord (Suhrke and Samset Reference Suhrke and Samset2007).

Measuring the independent variables

The literature identifies four main sets of provisions contributing to successful peace accords: third-party intervention (Fortna Reference Fortna2003; Hartzell et al. Reference Hartzell, Hoddie and Rothchild2001; Mattes and Savun Reference Mattes and Savun2009), power-sharing (Fontana Reference Fontana2018; Hartzell and Hoddie Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2003, Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2007; Lake and Rothchild Reference Lake and Rothchild1996; Mattes and Savun Reference Mattes and Savun2009; McEvoy and O'Leary Reference McEvoy and O'Leary2013; McGarry and McCulloch Reference McGarry and McCulloch2017), territorial self-governance (Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Weidmann and Gleditsch2011, Reference Cederman, Hug, Schädel and Wucherpfennig2015; Kuperman Reference Kuperman2015; Lake and Rothchild Reference Lake and Rothchild1996; Neudorfer et al. Reference Neudorfer, Theuerkauf and Wolff2020; Walsh Reference Walsh2018) and transitional justice (Fontana et al. Reference Fontana, Siewert and Yakinthou2020b; Loyle and Appel Reference Loyle and Appel2017). To operationalize these four factors, we include four independent variables (INT, PS, TSG and TJ, respectively) based on the text of the political agreements as coded in the PAIC data set (Fontana et al. Reference Fontana, Kartsonaki, Neudorfer, Walsh, Wolff and Yakinthou2020a).Footnote 5 Each variable is coded as 1 if it is included in a political agreement; it is coded as 0 otherwise.

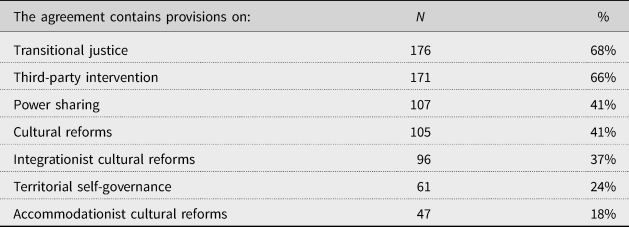

To test our two hypotheses on the relationship between cultural reforms and the success of peace agreements, we generate two binary variables – CI_ACC and CI_ITG – to code for the presence, in each agreement, of accommodationist and/or integrationist reforms, respectively. Table 3 shows the number and share of peace agreements including specific clauses as described above.

Table 3. The Features of Peace Agreements

Note: There is a total of 258 peace agreements in the sample; 38 peace agreements envisage both integrationist and accommodationist cultural provisions.

Provisions on transitional justice and third-party intervention are the most frequently encountered in our sample, appearing in more than 65% of peace agreements. Cultural reforms are present in 41% of pacts, suggesting that, despite being often overlooked by scholars, they are a core element of peace settlements.

Our data challenge existing assumptions that accommodation is the prevalent approach to cultural reform in peace processes (Nagle Reference Nagle2014). In fact, we find that cultural reforms endorsing an integrationist approach appear about twice as often as accommodationist cultural reforms in pacts concluded between 1989 and 2017. This suggests that negotiators broadly endorse the positive impact of integrationist cultural reforms on post-conflict reconciliation, while overlooking the potential contribution of accommodationist cultural provisions. This finding makes our research even more relevant to the theory and practice of conflict resolution.

On top of the peace agreement-related variables, we use additional controls to account for conflicts' and countries' characteristics that we expect may affect a peace process. We include two controls to account for the intensity and core incompatibility of conflicts (cum_conflict_intensity and incompatibility). Both controls rely on coding from the UCDP (2018). The former variable captures the intensity of the conflict in terms of the total number of battle deaths recorded until the conclusion of the political agreement. While controversies remain as to the impact of many conflict characteristics, there is a general agreement that more intense civil wars are more likely to recur (Mattes and Savun Reference Mattes and Savun2009).

The variable ‘incompatibility’ maps the fundamental issue at stake in the conflict. Following coding from the UCDP (2018), it allows us to identify territorial or secessionist conflicts (incompatibility = 0), where violence aims at ‘the change of the state in control of a certain territory … secession or autonomy’ (Themnér Reference Themnér2018: 3). It distinguishes them from conflicts fought over the control of the central government (incompatibility = 1), where violence aims at ‘the replacement of the central government, or the change of its composition’ (Themnér Reference Themnér2018: 3).

Finally, we include three variables that capture countries' characteristics. These variables are wealth (lnwdi_gdpcapcur), population size (Inwdi_pop) and population diversity (al_ethnic). Wealth has been demonstrated to be in an inverse relationship with the recurrence of civil war (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003; Walter Reference Walter2004). On the contrary, a large population size may favour the resumption of violent conflict (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003). For both wealth and population measures, we rely on data from the World Bank's World Development Indicators (namely, GDP per capita in current US$ and population). As is customary, we take the variables' logarithmic transformations to decrease the value range. Finally, we include, as a measure of diversity, an index of ethnic fractionalization at the state level (Alesina et al. Reference Alesina, Devleeschauwer, Easterly, Kurlat and Wacziarg2003). Table 4 summarizes the main descriptive statistics for the conflict and country-related control variables.

Table 4. Summary Statistics of Conflict and Country-Related Control Variables

Note: There is a total of 258 peace agreements in the sample.

Empirical model

To investigate the contribution of the inclusion of cultural reforms to successful peace agreements, we estimate the association between including at least one cultural provision in peace agreements and the cumulative number of battle-related deaths in the five years following the conclusion of the agreement.

We adopt a negative binomial specification to account for the fact that the regressand is a positively skewed count variable. In addition, a negative binomial specification allows for over-dispersion, which seems to be an issue in the data (see Table 1).

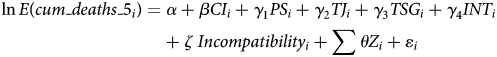

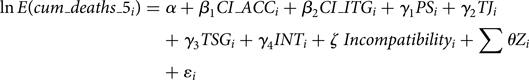

Using a negative binomial specification, the coefficients we estimate represent the link between a one-unit change in the respective independent variable and the logarithm of the expected incidence of the dependent variable and can thus be interpreted as the percentage effect of the former on the latter. We estimate the relationship between cultural reforms and post-agreement violence using the model described below:

where the subscript i refers to the peace agreement; $cum\_deaths\_5$![]() is the cumulative number of battle deaths occurred in the five years following the conclusion of the agreement; CI is an indicator which equals 1 if the agreement includes a cultural reform; PS, TJ, TSG and INT are a set of dummies indicating the presence in the peace agreement of provisions on power-sharing, transitional justice, territorial self-governance and third-party intervention, respectively. Incompatibilty is an indicator variable which equals 0 for territorial conflicts and 1 for conflicts fought over the control of the central government. Finally, the vector Z comprises the set of additional variables described above which control for the characteristics of the conflicts and of the countries at issue. The link between cultural reforms and the conclusion of successful peace processes is captured by coefficient β.

is the cumulative number of battle deaths occurred in the five years following the conclusion of the agreement; CI is an indicator which equals 1 if the agreement includes a cultural reform; PS, TJ, TSG and INT are a set of dummies indicating the presence in the peace agreement of provisions on power-sharing, transitional justice, territorial self-governance and third-party intervention, respectively. Incompatibilty is an indicator variable which equals 0 for territorial conflicts and 1 for conflicts fought over the control of the central government. Finally, the vector Z comprises the set of additional variables described above which control for the characteristics of the conflicts and of the countries at issue. The link between cultural reforms and the conclusion of successful peace processes is captured by coefficient β.

To better understand how specific approaches to cultural reforms relate to the successful conclusion of peace agreements, we modify the model in Equation (1) to allow for heterogeneous effects depending on the type of reform (accommodationist or integrationist). To this end, we replace variable CI with two dummy variables, $CI\_ACC\;$![]() and $CI\_ITG$

and $CI\_ITG$![]() , indicating the presence in the peace agreement of accommodationist and integrationist provisions, respectively. The modified model is:

, indicating the presence in the peace agreement of accommodationist and integrationist provisions, respectively. The modified model is:

In addition, we investigate whether the inclusion of cultural reforms is associated with different outcomes depending on the type of conflict (territorial or governmental) addressed by the peace agreement. To this end, we split our original sample S into two subsamples S terr and S gov, so that S terr includes the 65 peace agreements addressing territorial conflicts, and S gov includes the 193 peace agreements addressing governmental conflicts. Then we replicate the analyses on subsamples S terr and S gov using the following model:

Furthermore, to study the relationship of interest over a longer time frame, we use as dependent variable $cum\_deaths\_10_i$![]() , which captures, for each peace agreement i, the cumulative number of battle deaths occurring in the ten years following the conclusion of the agreement.

, which captures, for each peace agreement i, the cumulative number of battle deaths occurring in the ten years following the conclusion of the agreement.

Throughout the analysis we use robust standard errors clustered at the conflict level to allow for correlation between peace agreements which address the same conflict.Footnote 6

Finally, it is worth remarking that the usual checks for collinearity between independent variables did not raise any concern. In fact, a high level of correlation is only found between variables ‘Cultural reforms’ and ‘Integrationist cultural reforms’, which are never used together in our analysis.Footnote 7

Results

Column 1A in Table 5 presents the negative binomial regression estimates from Equation (1). The coefficient for the inclusion of cultural reforms in peace processes is not statistically significant, suggesting that the addition of a cultural reform in an intra-state peace agreement per se does not significantly contribute to reducing post-agreement violence. The same holds for provisions on power-sharing, territorial self-governance and transitional justice. In contrast, the inclusion of clauses on third-party intervention is associated with an 83% decrease in battle-related deaths in the five years following a peace agreement (significant at the 5% level). Therefore, our findings broadly confirm the existing literature in identifying third-party involvement as pivotal for the termination of violent intra-state conflicts (Walter Reference Walter2004).

Table 5. Cultural Reforms and the Success of Peace Processes

Notes: An observation represents one peace agreement. The estimates come from negative binomial regressions; cluster-robust standard errors (by conflict) are in parentheses. ‘ln(α)’ is the estimate of the log of the dispersion parameter. Further controls (Z i) include measures of the cumulative conflict intensity, GDP per capita, population size and ethnic fractionalization. Twenty-seven peace agreements are dropped due to missing values in some of the explanatory variables. ***, ** and * denote statistical significance at 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively.

To better understand the link between the inclusion of cultural reforms and successful peace accords, we allow for heterogeneous effects depending on the type of reform (accommodationist or integrationist), so that different approaches to cultural reforms may have different effects on post-agreement violence. We will first discuss results on accommodationist cultural reforms and then turn to results on integrationist cultural reforms.

The distinct impact of accommodationist cultural reforms is obtained through the negative binomial estimation of Equation (2). Outcomes are reported in column 2A of Table 5.

The inclusion of accommodationist cultural reforms in intra-state peace agreements is significantly associated with an 83% decrease in the number of battle-related deaths in the five years following the agreement. Column 3A in Table 5 replicates the latter analysis while looking at a longer time frame. It uses as dependent variable the cumulative number of battle-related deaths in the ten years following the agreement (rather than five years). Outcomes show that even in the long term the inclusion of accommodationist cultural reforms in a peace agreement is strongly and significantly associated with success.Footnote 8

To detect the impact of our hypothesized reputational effect, we further investigate the relationship between cultural reforms and post-agreement violence by allowing for heterogeneous effects depending on the type of incompatibility (territorial or governmental), so that the association between a certain approach to cultural reforms and the outcome variable may vary depending on the nature of the conflict. Results are shown in panel B in Table 5. We first look at territorial conflicts only (subsample S terr) and estimate the negative binomial model described in Equation (3). Results are displayed in column 1B. We then replicate the analysis considering only governmental conflicts (subsample S gov). Outcomes are shown in column 2B. We then look at a longer time frame. Columns 3B and 4B replicate the results presented in column 1B and 2B, respectively, while using as dependent variable the cumulative number of battle-related deaths in the ten years following the agreement. The association between accommodationist cultural reforms and battle deaths is negative – though not precisely estimated – regardless of the type of incompatibility underlying the conflict. The loss in significance of the estimated coefficients as compared to specifications in column 2A and column 3A is likely due to the reduced power that we get from performing the analysis on (smaller) subsamples rather than the entire sample. Reassuringly, the sign of the estimated coefficients is maintained across all specifications. This result holds in both the medium and the long term.

This outcome is in line with our expectation that all peace accords – regardless of the core conflict incompatibility – benefit from the inclusion of accommodationist cultural reforms because of the beneficial reputational effect of accommodationist provisions. We also find no evidence of a mobilization effect of accommodationist cultural reforms in the five and ten years following a peace accord. These findings lead us to confirm our Hypothesis 1.

The distinct impact of integrationist cultural reforms is obtained through the negative binomial estimation of Equation (2). We find that the association between integrationist cultural reforms and battle-related deaths is positive in both the medium (column 2A of Table 5) and the long term (column 3A in Table 5), though it is only significant in the latter time frame. Thus, contrary to extensive evidence on the beneficial long-term impact of integration (Nagle Reference Nagle2014; Ross Reference Ross2007; Taylor Reference Taylor and Taylor2009), our outcomes show that that the inclusion of integrationist cultural reforms may not contribute to ending violence in the medium to long term – quite the contrary. In line with Elisabeth King and Cyrus Samii's (Reference King and Samii2020) argument, this may be because integrationist reforms do not contribute to reassuring the conflict parties. We add that this result may also be explained by the detrimental reputational effect of integrationist cultural reforms in the fragile post-agreement context.

To further investigate the validity of our hypothesized reputational effect, we examine the impact of integrationist cultural reforms on territorial and governmental conflicts, respectively (results reported in panel B in Table 5). In line with our theoretical expectations, the estimated association between integrationist cultural reforms and battle deaths is positive across incompatibility types and time horizons. We suggest that this is because of the detrimental impact of integrationist reforms on the reputation of negotiating leaders as legitimate representatives of their group's grievances. This association is not precisely estimated for governmental conflicts, whereas it is significant – and sizeable – for territorial conflicts. Supporting previous studies (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Lake and Rothchild Reference Lake and Rothchild1996), our model suggests that the inclusion of integrationist cultural reforms may exacerbate conflict where leaders' reputation and legitimacy is most closely tied to the cultural distinctiveness of the group (as in territorial conflicts). Therefore, we can confirm our Hypothesis 2.

Panel B in Table 5 shows that context also partially affects the ultimate impact of both cultural policy and other mechanisms (including power-sharing and third-party intervention), so that they may be more effective in agreements addressing governmental conflicts and less beneficial in those addressing territorial conflicts or vice versa (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985). While perhaps unsurprising, this finding supports long-lasting calls for more comprehensive conflict analysis and for a context-sensitive formulation of cultural policy in fragile and conflict-affected contexts (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985).

All in all, our cross-case empirical investigation suggests that the relationship between cultural reforms and the success of peace agreements depends on the approach to reform (on a spectrum between the integration and accommodation of conflict parties). The inclusion of at least one accommodationist cultural reform in a peace accord is associated with a significant reduction in post-agreement violence across conflict types. In contrast – and challenging established evidence on the impact of integration on long-term reconciliation – the inclusion of at least one integrationist cultural reform in a peace accord does not contribute to a significant reduction in post-agreement violence. In fact, it may exacerbate particularly separatist conflicts. In terms of mechanism, we propose that this is because of the detrimental effect of integrationist cultural reforms on the reputation of negotiating leaders as legitimate political representatives of their respective conflict groups.

Robustness checks

We performed several tests to verify the reliability of our baseline results. In particular, we checked whether:

1. Any specific agreement disproportionately influences the analysis – by replicating our baseline estimations while sequentially dropping each of the 258 peace agreements;

2. The set of agreements generated by any specific conflict disproportionately influences the analysis – by replicating our baseline estimations while sequentially dropping all accords referring to each of the 58 conflicts;

3. Our results are robust when controlling for – in turn – yearly and regional indicators;

4. Our results are robust to a more conservative approach whereby we drop from the sample recent pacts, that is, pacts for which the exact value of the dependent variable cannot be computed due to data limitations.

These additional analyses reinforce our confidence in the baseline findings as results are robust to all alternative approaches and specifications considered.Footnote 9

An important caveat to our results is that they cannot be interpreted in a causal fashion. The inclusion of specific reforms of cultural institutions in a peace accord is likely not random with respect to the determinants of how successful the accord will be. Reasonably, negotiators include in the accords the reforms they deem more likely to facilitate sustainable peace. Nonetheless, our outcomes provide strong suggestive evidence of the sign and size of the association between different approaches to cultural reforms and successful peace accords. We illustrate our argument through a qualitative analysis of Northern Ireland's Good Friday Agreement.

Qualitative analysis

We employed our quantitative analysis to guide the selection of a case study to test the validity of our theoretical interpretation of the statistical model, as best practice in mixed research designs (Beach Reference Beach2019; Lieberman Reference Lieberman2005). We therefore examine an example of accord regulating a separatist conflict: Northern Ireland's 1998 GFA. If our theory on the reputational effect of cultural reforms is valid, we would expect two patterns. First, we would expect representatives of conflict parties to tie their reputation as legitimate political representatives of their respective conflict groups to the inclusion and implementation of accommodationist cultural provisions during and after peace negotiations. Second, we would expect representatives of conflict parties to distance themselves from the integrationist cultural provisions in the negotiation and post-conflict phase. If our theory is wrong, we would find no evidence of reputational effects of cultural provisions in Northern Ireland.

The Good Friday Agreement

The GFA aimed to end Northern Ireland's 30 years of ‘Troubles’, a low-scale violent conflict between Nationalists (largely Catholic) and Unionists (largely Protestant). As former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair reflects in his memoirs, ‘A culture had grown up around the dispute. The Unionists didn't simply have a political disagreement with the Nationalists, nor simply a religious difference; they had a different music, a different way of speaking’ (Blair Reference Blair2010: 154).

The GFA squared the circle of competing local, regional and international aspirations through a complex constitutional design based on extensive devolution for Northern Ireland as part of the UK, power-sharing in Belfast and British–Irish institutionalized cooperation. These institutional arrangements are explicitly underpinned by parity of esteem for the two local ‘traditions’ of Unionists and Nationalists (McGarry and O'Leary Reference McGarry and O'Leary2006a, Reference McGarry and O'Leary2006b; O'Leary Reference O'Leary1999).

The reputational effect of accommodationist cultural reforms

Analysis of the negotiation and implementation of the GFA provides strong evidence that representatives of conflict parties tie their reputation to the inclusion and implementation of accommodationist cultural provisions. The beneficial reputational effect of accommodationist cultural provisions is particularly evident regarding the negotiations over the status of the Irish language. According to mediators, debates over the protection and promotion of languages other than English remained a ‘stumbling block. It was crazy’ (Tony Blair, quoted in Campbell and Stott, Reference Campbell and Stott2007: 296). On the one hand, negotiators' memoirs and polling data confirm the well-established reassuring effect of accommodationist language reforms. A 1998 poll shows that most Catholic respondents deemed the use of the Irish language and Irish-language schooling as essential to the conclusion of the agreement (Irwin Reference Irwin1998: 20). Mediators echo the literature in their emphasis on accommodation of Irish as a powerful symbol of the shifting identity of the state in an inclusive direction (Blair Reference Blair2010; O'Leary Reference O'Leary2019). In this light, the insistence of Nationalist parties that ‘Irish had no official status in the North. We were determined to change this’ is perhaps unsurprising (Adams Reference Adams2003: 348).

On the other hand, first-hand reports corroborate the important reputational effect of accommodationist cultural reforms on the legitimacy of the political representatives of all conflict parties. Northern Ireland Secretary Mo Mowlam (Reference Mowlam2003: 173) recalled that ‘All the N. Ireland parties went through times when they had trouble holding their followers onside.’ On the Nationalist side, Sinn Féin (SF) leaders ‘feared a split’ (Blair Reference Blair2010: 197; Dixon Reference Dixon2002), providing strong incentives to support policies dear to their base. Polls show that public use of the Irish language and Irish-language schools were deemed essential to the conclusion of a peace agreement by 81% and 75% of SF supporters, respectively (Irwin Reference Irwin1998: 35). These issues were less salient to the Social Democratic and Labour Party's (SDLP) base (Irwin Reference Irwin1998), but the SDLP feared outflanking as ‘in the past Sinn Fein had collapsed the show by claiming the SDLP were selling out’ (Blair Reference Blair2010: 170). Thus, Janet Muller refers to ‘the need for the nationalist parties to at least appear to be promoting the Irish language’ (Muller Reference Muller2010: 67), while third-party mediators supported these initiatives in order to ‘help Adams carry the hard men in the republican movement with him’ (Dixon Reference Dixon2002).

On the Unionist side, Blair recalls that ‘David Trimble [Ulster Unionist Party] was under perpetual pressure from Ian Paisley, who turned up outside Castle Buildings to condemn the whole thing as a monstrous sell-out’ (Blair Reference Blair2010: 167). Under 15% of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) supporters deemed the use of Irish unacceptable, but this percentage increased to about 40% of Paisley's supporters (Irwin Reference Irwin1998: 34), suggesting a need for Trimble to accommodate their concerns through a ‘preventive strike in a culture war’ (O'Leary Reference O'Leary2019: 265). Thus, in the last night of the GFA negotiation, as protection for the Irish language was being debated, ‘It turned out there was some obscure language called Ullans, a Scottish dialect spoken in some parts of Ulster which was the Unionists’ equivalent of the Irish language’ (Blair Reference Blair2010: 174). Similarly, Campbell recalls that ‘We then had another history lesson by DT [David Trimble] on the importance of Ullans … We had effectively announced the deal was done, give or take a bit or two at the edges and here we were, with DT ready to unpick the whole thing over this’ (Campbell and Stott Reference Campbell and Stott2007: 298).

It is reasonable to interpret these debates as ‘rival political actors perform[ing] contrasting nationalist and unionist scripts in order to bring hostile audiences towards accommodation’ (Dixon Reference Dixon2019: 33). These arguments, however, were so heated that they led mediators to contemplate the prospect that ‘We had failed to secure an agreement after all because of a Scottish Ulster dialect called Ullans, and so the war in Northern Ireland would go on’ (Blair Reference Blair2010: 174). As a result of these last-minute debates, the GFA came to include the following accommodationist clause: ‘All participants recognise the importance of respect, understanding and tolerance in relation to linguistic diversity, including in Northern Ireland, the Irish language, Ulster-Scots and the languages of the various ethnic communities, all of which are part of the cultural wealth of the island of Ireland’ (Agreement The 1998: 24).

In line with broader commitment to parity of esteem, this accommodationist cultural provision preserved the reputation of Unionist and Nationalist leaders ‘as hardliners … to maintain the confidence of the party and the electorate’ in the context of potential ethnic outbidding (Dixon Reference Dixon2019: 141). They were particularly instrumental to the UUP lifting their final objections to the GFA.

Analysis of the implementation of the GFA over the following decade further corroborates the reputational effect of cultural provisions. Successive opinion polls confirm that linguistic rights and the implementation of the GFA's linguistic provisions remained twice as important to SF supporters than to other Nationalists (Irwin Reference Irwin2001; Reference Irwin2003). The established tie between their leaders' reputation as legitimate political representatives and accommodationist cultural reforms partly explains SF's drive to expand Irish-medium education throughout Northern Ireland (Ó Baoill Reference Ó Baoill2007; Sharma Reference Sharma2021) and its insistence in including provisions for the introduction of an Irish-language act in the 2006 St Andrews Agreement (Coulter et al. Reference Coulter, Gilmartin, Hayward and Shirlow2021; McMonagle Reference McMonagle2010). The same reputational effect also explains Unionist parties' insistence on equal funding and support for the linguistic and cultural activities of Ulster Scots (Coulter et al. Reference Coulter, Gilmartin, Hayward and Shirlow2021; Fontana Reference Fontana2016; O'Leary Reference O'Leary2019).

Our theory proposes that, together with well-established reassuring effects, accommodationist cultural reforms aid the success of intra-state peace accords by protecting negotiating leaders' reputation as legitimate political representatives of their respective conflict groups. On the one hand, we find that third parties understood and exploited this reputational effect during and after the GFA negotiations, harnessing ‘parity of esteem’ to provide both internal and external legitimacy to the negotiating parties. On the other hand, and confirming our theoretical expectations, we find extensive evidence that representatives of conflict parties tied their reputation to the inclusion and implementation of accommodationist cultural provisions during the GFA negotiations and in the following decade.

The reputational effect of integrationist cultural provisions

To evaluate the validity of our theory on the reputational effect of cultural provisions, we further explore the negotiation and implementation of the GFA's best-known integrationist provision: ‘An essential aspect of the reconciliation process is the promotion of a culture of tolerance at every level of society, including initiatives to facilitate and encourage integrated education’ (Agreement The 1998: 23).

In line with our expectations of a negative reputational effect of integrationist cultural provisions, we find extensive evidence that representatives of conflict parties distanced themselves from this provision in the negotiation and post-conflict phase.

There is ample evidence that provisions to expand integrated schooling were only embedded in the GFA because of the insistence of two cross-community parties: the Northern Ireland Women's Coalition and the Alliance Party (Albert Reference Albert2009; Fearon and McWilliams Reference Fearon and McWilliams1998). Corroborating the importance of leaders' reputation, Mowlam (Reference Mowlam2003: 363) recalled that, ‘Among the majority of political parties, excluding the Women's Coalition and the Alliance Party, all are lukewarm about integrated education, partly because it would begin to break down a clear voting block for each of their parties.’

In the aftermath of the GFA, successive SF and DUP education ministers paid lip service to integrated schools. However, the education policies implemented in the following decade were found to be the ‘opposite of encouraging and facilitating’ integrated education by a 2014 High Court ruling (Fergus Reference Fergus2014). The rhetoric of political and educational leaders also gradually shifted away from integration and towards the promotion of tolerance and collaboration through the existing (separate) school sectors (Fontana Reference Fontana2016; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006). In other words, representatives of conflict parties distanced themselves from integrationist cultural provisions, corroborating our hypothesized reputational effect of cultural reforms.

Additional considerations

While broadly confirming our theoretical hypotheses and quantitative results, qualitative evidence from the GFA also suggests that accommodationist cultural reforms may have a mobilization effect over ten years after the conclusion of a peace accord. Specifically, the case of Northern Ireland suggests that the embedded ties between leaders' reputation and specific cultural provisions may provide additional flashpoints for future confrontation. Debates over the Irish language act are a case in point.Footnote 10 On the one hand, there is evidence of broad cross-community support for an Irish language act as embedded in the 2006 St Andrews Agreement (McMonagle Reference McMonagle2010). On the other hand, SF's reputation became inextricably linked with the introduction of the act. Conversely, minority language rights remained unacceptable to over 40% of DUP supporters (Irwin Reference Irwin2001). Concerns with their reputation and vulnerability to populist challenges (Dixon Reference Dixon2019) may have partly motivated the decision by successive DUP representatives to prevent the adoption of an Irish language act. As DUP leader Arlene Foster put it at a DUP campaign event, ‘If you feed a crocodile it will keep coming back and looking for more’ (McAdam Reference McAdam2017).

Ultimately, long-standing disputes over the status of the Irish language in Northern Ireland added to the strains that triggered the resignation of the SF deputy First Minister and the collapse of the power-sharing executive in early 2017 (Coulter et al. Reference Coulter, Gilmartin, Hayward and Shirlow2021; O'Leary Reference O'Leary2019). In his resignation speech, Martin McGuinness deplored that ‘for those who wish to live their lives through the medium of Irish, elements in the DUP have exhibited the most crude and crass bigotry’ (quoted in O'Leary Reference O'Leary2019: 299).

Conclusion and further research

In this article we propose that cultural reforms, particularly accommodationist cultural reforms, are a valuable component of peace accords. Specifically, we suggest that, beyond reassuring formerly warring parties in separatist conflicts, accommodationist cultural reforms have a beneficial reputational effect for negotiating leaders across all types of conflict. In other words, cultural provisions impact on negotiating leaders' reputation as legitimate political representatives of their respective conflict groups. By strengthening this reputation in the fragile negotiation and post-agreement phase, accommodationist cultural reforms help prevent the leadership challenges and group factionalization which typically lead to post-agreement violence. Conversely, integrationist cultural reforms undermine the reputation of negotiating leaders as legitimate political representatives of their group's grievances in the medium to long term.

Examining all intra-state political agreements concluded between 1989 and 2016, we find strong suggestive evidence of a beneficial reputational effect of accommodationist cultural reforms across all conflict types. In contrast, despite the overwhelming emphasis of peace agreements on integrationist cultural initiatives (see Table 3), the inclusion of integrationist cultural provisions erodes the reputation of negotiating leaders, paving the way for leadership challenges and factionalization, particularly in separatist conflicts.

Our analysis of Northern Ireland's GFA confirms that accommodationist cultural reforms help reassure warring parties in a separatist conflict and bring valuable reputational benefits to the negotiating leaders. Conversely, due to their problematic reputational effect, leaders typically distance themselves from integrationist cultural provisions both during negotiations and in their immediate aftermath.

There is a crucial caveat to our findings. In this study, we only focus on the promises of intra-state peace agreements. Whilst there is a strong association between de jure and de facto recognition of ethnic groups in cultural domains (King and Samii Reference King and Samii2020), further research aiming to evaluate the relative merits of accommodationist and integrationist approaches to cultural reform should also examine the implementation of the accords and their impact on long-term reconciliation. Thus, our findings should be systematically tested against other peace processes.Footnote 11 Further cross-case analysis of the type of negotiating actors, of the source of their legitimacy, and of the level of group fragmentation, would help expand on our conclusions and test their applicability in different contexts. Finally, it would be useful to explore the extent to which third parties have harnessed cultural provisions to provide internal and external legitimacy to negotiating parties across different conflicts.

The practical implications of this study are clear. Peace processes typically mitigate commitment problems through the inclusion of provisions for power sharing and third-party intervention. The inclusion of accommodationist cultural reforms may have equally powerful reassuring and reputational effects, particularly where there are high risks of leadership challenges and factionalization. Moreover, accommodationist cultural reforms do not typically pave the way for the mobilization of previously warring groups and the resumption of violence in the medium and long term.Footnote 12 Therefore, they may be a useful but often overlooked complement to territorial forms of autonomy, which are more controversial and more costly.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.62.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the Political Settlements Research Group at the University of Birmingham, especially Natascha Neudorfer and Stefan Wolff, for their feedback on earlier drafts of this paper. Previous drafts of this paper have been presented and received feedback at the 2020 DSA annual conference, 2020 ECPR annual conference and 2020 PSA Ethnopolitics Colloquium. This research has been made possible by a British Academy/Leverhulme Small Grant (SRG\170187).