As an altricial species, humans require caregivers for survival, and compared to nonhuman primates, the duration of time human offspring are dependent on their parents and other caregivers is substantially greater (Humphrey, Reference Humphrey2010). This prolonged period of dependence on caregivers highlights the first years of life as a crucial time for development and underscores how variations in care during this period may affect children’s health and functioning throughout the lifespan. The necessary components for survival (protection from harm and provision of food, shelter, and clothing) require at least some degree of physical contact or closeness between children and those who care for them. In addition, expected experiences like the receipt of caregiver provided stimulation and nurturance, typically in the form of touch, play, and conversation, require close proximity between caregivers and children. The present review highlights research on caregiver–child proximity from multiple scholarly disciplines and seeks to highlight the importance of characterizing early caregiving experiences for later adaptive and maladaptive functioning.

The devastating consequences experienced by children in institutional care (orphanages) related to the absence of close contact with a caregiver in early life make clear that caregiving interactions are foundational to healthy development across domains. Children reared in orphanages, given the high child-to-caregiver ratios and rotating staff, tend to receive reduced responsive adult interactions and touch (Zeanah et al., Reference Zeanah, Smyke and Settles2008). Yet, some children in institutional care form secure attachment relationships with those who care for them (Smyke et al., Reference Smyke, Zeanah, Fox, Nelson and Guthrie2010), indicating the possibility that even in these depriving settings some children were likely receiving adequate attention from a reliable caregiver. Variation in the quality of caregiving interactions is not only found among institutional settings; children living in families range widely in their caregiving experiences. Of the over 600,000 U.S. children who have maltreatment reports each year, approximately 75% are classified as “neglect” (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau, 2021), indicating that despite residing in families, many children experience supervisory, medical, and/or psychosocial deprivation. Assessing children’s physical contact with those that care for them is a crucial aspect of understanding their early environment.

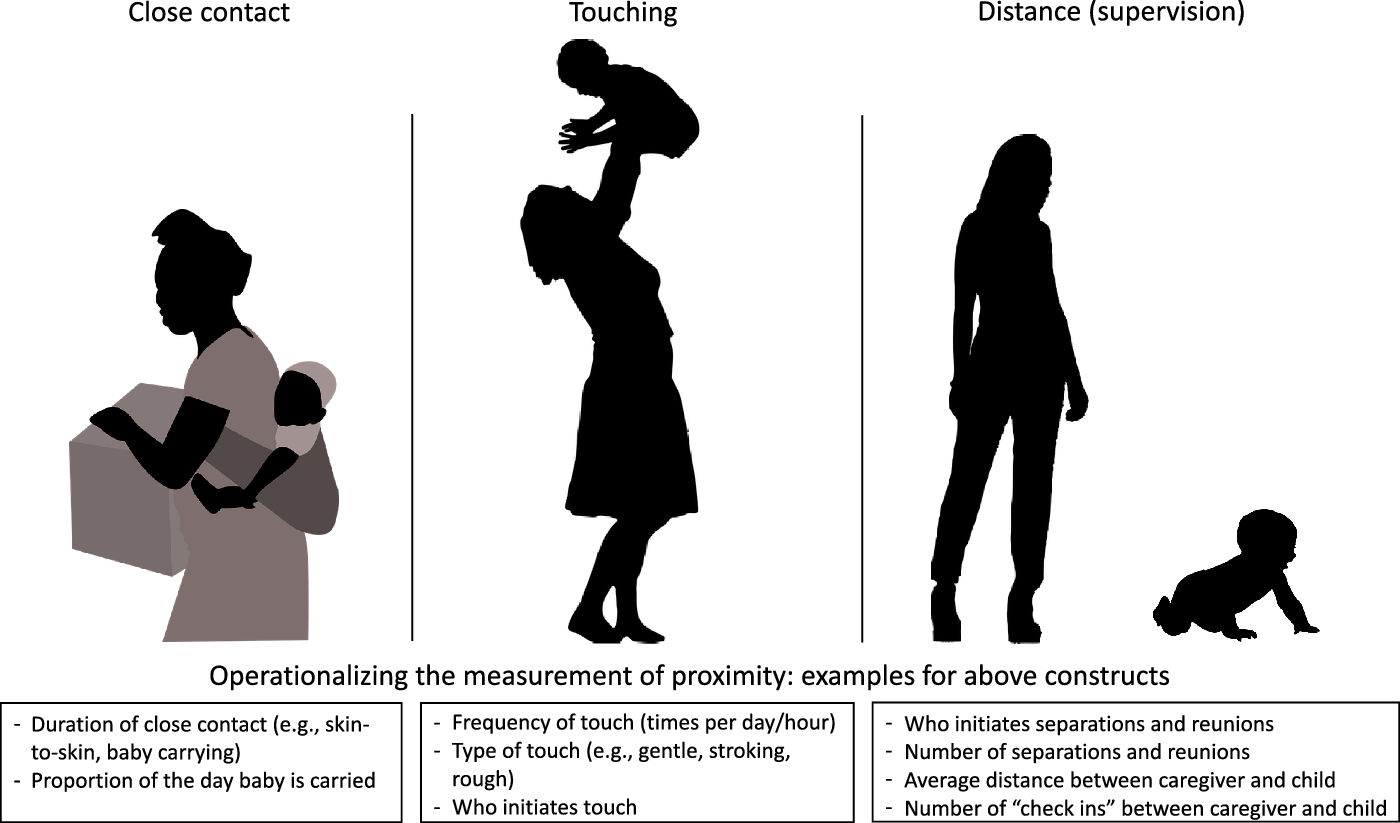

In this article, we (briefly) review: (1) studies of caregiver–child proximity across disciplines (e.g., anthropology, clinical psychology, developmental science), (2) predictors of patterns of caregiver–child proximity, (3) child outcomes linked to variation in proximity with a caregiver, and (4) how proximity may be considered in relation to current conceptualizations of early experience, and specifically, dimensional models of adversity. Additionally, we highlight the breadth and variety of measurement methods applied to studying caregiver–child proximity (see Figure 1 and Table 1). Figure 1 provides a visual description of how measurement of caregiver–child proximity may be operationalized, specifically relating to assessments of close contact (e.g., infant carrying, duration carried), caregiver–child touch (e.g., frequency, duration, and quality of touch), and physical distance (e.g., caregiver–child distance during activities, frequency of “check-ins”). Table 1 provides details of proximity measurement (e.g., use of sensors to track spatial proximity, self-report measures of frequency of touch between parents and children) used in a selected sample of studies to illustrate the breadth of measurement methods and highlight the variety of tools applied to assessing caregiver–child proximity.

Figure 1. Approaches to operationalizing caregiver–child proximity. Common methods of measuring caregiver–child proximity include quantifying duration of close contact, baby carrying, or skin to skin contact; frequency of touching; distance between caregiver–child dyads; caregiver supervision of child.

Table 1. Example cases to illustrate measurement approaches for assessing caregiver–child proximity

It is important to note that the majority of literature identified in this review includes mother–child dyads. Though differences based on caregiver gender or relationship to the child is an important area of study (see future directions for additional discussion), when not discussing specific studies we use the term “caregivers” to be inclusive of biological parents (e.g., mothers, fathers) as well as other caregivers (e.g., adoptive and foster parents or other family members in a caretaking role). Given the breadth of literature on mother–child interactions, caregiving style, and breastfeeding, the review focuses only on studies measuring proximity (e.g., touch, distance). This review aims to highlight the relevance of caregiver–child proximity to the study of early experience and the importance of capturing variation in caregiver–child proximity for later adaptive and maladaptive functioning.

Contextualizing caregiver–child proximity within dimensional models of early experience

Situating early caregiving environments (including proximity) within dimensional frameworks enables us to test hypotheses about whether specific features of early caregiving are related to child outcomes. The majority of research studies on early adversity consider either a single type of adverse experience (e.g., physical abuse), group experiences like abuse and neglect together in a “maltreatment” category, or count up the types of events experienced using a cumulative approach (for review and discussion of frameworks of adversity, see [McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan, Humphreys, Belsky and Ellis2021]). Dimensional models, an alternative approach, jointly consider similar experiences along dimensions of severity to capture like forms of adversity (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan, Humphreys, Belsky and Ellis2021). The dimensional model of adversity (DMAP) focuses on threat and deprivation (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan and Lambert2014), and has gained a growing body of empirical evidence (including from this special issue) that supports the use of a dimensional framework for linking early environmental experiences to specific outcomes. Another dimensional approach, developed by Ellis et al. (Reference Ellis, Figueredo, Brumbach and Schlomer2009), characterizes environments along dimensions based on environmental harshness and unpredictability. Harsh environments, broadly defined as externally caused levels of morbidity-mortality, and unpredictable environments (i.e., variation in harshness over time), are theorized to be fundamental in influencing early development. Utilizing extant dimensional frameworks to characterize caregiver–child proximity emphasizes the importance of capturing both qualitative (e.g., type of touch, responsive care) and quantitative (e.g., frequency of touch, physical distance) aspects of proximity to better characterize children’s early caregiving environment along a continuum of lived experiences (e.g., enriched to deprived, harsh to nurturing, predictable to unpredictable).

In our view, variation in caregiver–child proximity most clearly aligns with the dimension of deprivation. Expected experiences like the receipt of caregiver-provided stimulation and nurturance (King et al., Reference King, Humphreys and Gotlib2019), typically in the form of touch, play, and conversation, require close proximity between caregivers and children. Conversely, the absence of close caregiver–child proximity is most strikingly observed in studies of children in institutional care; care associated with devasting consequences for later functioning (Goldman et al., Reference Goldman, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Bradford, Christopoulos, Ken, Cuthbert and Sonuga-Barke2020; van IJzendoorn et al., Reference van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Duschinsky, Fox, Goldman, Gunnar and Sonuga-Barke2020). In the following review, we present research characterizing caregiver–child proximity along a dimension and associated child outcomes. Further discussion situating caregiver–child proximity within dimensional frameworks is presented at the end of this review.

Theoretical perspective across disciplines

Nonhuman primate research

Research on nonhuman primates has improved our understanding of caregiver–offspring relationships, underlying neurobiological processes linked to proximity, and the severe impact of caregiver separation on young offspring. In this section, we present results from studies across different species of nonhuman primates involving aspects of caregiver–offspring relationships related to proximity. A typical physical relationship for primate infants is full and continuous contact with their mother (Pryce, Reference Pryce1996). Although carrying behavior is varied across species, caregivers in many primate species (e.g., macaques, titi monkeys, squirrel monkeys, and chimpanzees) maintain tactile bonds and engage in significant carrying behaviors with their infants (Ross, Reference Ross2001). Seminal work by Harlow (Reference Harlow1958) found that caregivers are necessary not only for the provision of sustenance, but also for providing physical support and nurturance to infants. Compared to human infants, most nonhuman primates are born with relatively developed motor skills, which allows them to engage in grasping behaviors and cling to their mother’s fur within minutes after being born (Ross, Reference Ross2001; Trevathan & McKenna, Reference Trevathan and McKenna1994). Some have speculated that the relative infrequent crying observed in mammalian infants is due to their ability to maintain closeness to their mothers (Esposito et al., Reference Esposito, Yoshida, Ohnishi, Tsuneoka, del Carmen Rostagno, Yokota and Kuroda2013). Thus, for nonhuman primates, the ability to maintain closeness is not solely determined by the mothers’ specific and overt actions, but also by proximity seeking in their infants.

Changes in proximity across developmental stage in nonhuman primates

Across species of nonhuman primates, differences in caregiver–offspring proximity can be seen as responsive to age and developmental stage of the offspring. As marmoset infants age, parents (mothers and fathers) initiate separations, which encourage socialization and development (Ingram, Reference Ingram1977). For example, initiating times of physical separation may be deliberate for marmosets, who, at around the third week of life, gradually begin to place their infants on tree branches and move away for short periods of time (Ingram, Reference Ingram1977). This behavior increases until, at around 6 weeks of age, the infant marmoset becomes comfortable climbing off their caregiver and inducing separations and reunions on their own (Ingram, Reference Ingram1977). However, despite marmoset infants experiencing a shift from wearing (e.g., infant traveling on its mothers back) to nonwearing (e.g., infant independent locomotion) parents continue to maintain supervision over their infants, as parents restrict their offspring’s movements and retrieve their infants if they travel too far away (Ingram, Reference Ingram1977). In macaque infants, as they gain more autonomy in movement, mothers closely supervise their infants and demonstrate protective behaviors (Hinde & Spencer-Booth, Reference Hinde and Spencer-Booth1967). Controlled separation, characterized by allowing infants to move independently and explore their environment with continued maternal supervision, promotes infant independence and development.

Costs and benefits to maintaining proximity

It is important to consider that there are costs and benefits to maintaining constant close contact. For example, closer proximity improves feeding for the infant, whereas greater distance provides more opportunities for the mother to complete her own feeding activity (Altmann, Reference Altmann1980; Johnson, Reference Johnson1986). In baboons, as infantsʼ age, given the energy expended to carry infants, mothers begin to transition their infants from being carried constantly, to independent locomotion under the mother’s close supervision, with proximity between infant and mother increasing until the infants are around 8 months old, when they are old enough to feed independently and no longer rely on their mothers for survival (Altmann & Samuels, Reference Altmann and Samuels1992). Mothers who carry infants orally or whose infants engage in fur-clinging (called “riders”), such as marmoset, langurs, and some strepsirrhine species, exude more caloric energy than species such as lemurs, aye-ayes, and marmosets, who leave their infants in nests parked in trees (called “parkers”). However, infant riders tend to have lower mortality rates than parkers, suggesting that there are some species benefits to the extra energy expenditure (Ross, Reference Ross2001).

Separation and reunion in nonhuman primates

As nonhuman primate infants age, mothers spend less time engaging in constant proximity with their infants. Although patterns of behaviors may be species dependent, most nonhuman primate species engage in periods of mother–offspring separation, supervision, and reunions. Researchers have explored infant physiological and behavioral reactions to forced separation, characterized as maternal deprivation; though the duration of separation has varied considerably in experimental studies (for additional reviews, see Parker & Maestripieri, Reference Parker and Maestripieri2011; Zhang, Reference Zhang2017). This line of research has been crucial for highlighting the importance of close contact (Harlow, Reference Harlow1958), as it allows for causal assessments to be made about infants during the absence of caregiving. Even brief separations of primate infants from their mother can represent a severe stressor (Pryce, Reference Pryce1996). Separation reactions in Goeldi’s monkeys includes a marked increase in motor behavior and activity of the HPA axis (Dettling et al., Reference Dettling, Pryce, Martin and Döbeli1998). When the infant Goeldi’s monkeys were reunited with their mothers, their stress reactions were reduced, suggesting that parental separation may be a powerful stressor for them (Hennessy, Reference Hennessy1986). Similarly, infant squirrel monkeys repeatedly separated from their mothers showed sustained high levels of cortisol and increasing agitated activity in response to separation (Coe et al., Reference Coe, Glass, Wiener and Levine1983). Even under separation periods of 3 hr, marked changes are noted in infant monkeys, such as lowered body temperature, hormonal stress responses, and cardiac arrhythmias (Сое et al., Reference Coe, Wiener, Rosenberg, Levine, Reite and Field1985). In a study of infant marmosets, those who experienced daily separation and deprivation of their parental caregivers exhibited increased stress responses and lethargic behaviors in response to reward systems (delivery of banana flavored milk following response to visual stimuli), behaviors similar to the symptoms of major depressive disorder (Pryce et al., Reference Pryce, Dettling, Spengler, Schnell and Feldon2004). Infant rhesus macaques who experience maternal separation can exhibit chronic behavioral repercussions, such as poor social skills, gaze aversion, self-injury, and huddling (Suomi & Harlow, Reference Suomi and Harlow1972). Infant rhesus macaques separated from mothers for more than 1 week additionally showed “despair” behaviors (e.g., quiet, withdrawn state; Gunnar et al., Reference Gunnar, Gonzalez, Goodlin and Levine1981). Reactions to separation appear to first include attempts to locate and reunite with one’s mother (Hennessy, Reference Hennessy1986). Following separation, infant squirrel monkeys exhibited more proximity seeking behavior with the mother upon reunion than monkeys who had not been separated (Hennessy, Reference Hennessy1986), perhaps to reduce the risk for future separations. A wide range of physiological and behavioral responses, including increased proximity seeking behavior from infants, have been observed following forced separation of primate infants from their mothers, indicating the potency of separation as a severe stressor. Given the degree to which primate infants rely on their caregivers for survival (Esposito et al., Reference Esposito, Yoshida, Ohnishi, Tsuneoka, del Carmen Rostagno, Yokota and Kuroda2013; Ross, Reference Ross2001), these stress responses to separation seem to provide critical signals to both mother and offspring regarding the importance of maintaining a close physical relationship for survival.

In addition to studies of parental separation, researchers have also investigated how nonhuman infants function when they are raised without their mother using research designs including isolation, peer-reared, and other-adult reared contexts. Early work investigating rearing experiences looked at how isolation impacted infant development, specifically investigating total isolation (e.g., no visual, auditory, or tactile contact) and partial isolation (e.g., caged separately but with auditory and visual contact). These extreme manipulations appear to cause severe cognitive and emotional deficits, as well as self-injurious behaviors (Cross & Harlow, Reference Cross and Harlow1965; Harlow et al., Reference Harlow, Dodsworth and Harlow1965; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Raymond, Ruppenthal and Harlow1966). Due to ethical concerns, isolation studies were stopped, and the focus turned to comparison of rearing approaches. For example, comparing mother-reared versus nursery-reared or peer-reared (Champoux et al., Reference Champoux, Coe, Schanberg, Kuhn and Suomi1989; Clarke, Reference Clarke1993), and mother-reared versus surrogate-reared (Kraemer et al., Reference Kraemer, Ebert, Schmidt and McKinney1991; e.g., use of an alternative to their mother such as an inanimate object or other “replacement” caregiver). These rearing histories appear to impact primate infants’ behavioral and physiological reactions to stress or separation. For example, rhesus macaque infants reared by their mothers respond to separation with protest reactions, while infants reared via an inanimate surrogate respond with a despair reaction (Kraemer et al., Reference Kraemer, Ebert, Schmidt and McKinney1991). Rhesus monkey infants who were raised in a nursery setting, as opposed to a mother-reared setting, displayed higher cortisol levels at age 4 weeks (Champoux et al., Reference Champoux, Coe, Schanberg, Kuhn and Suomi1989), whereas mother-reared rhesus monkeys had higher levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone (a hormone that stimulates the production of cortisol) following a stressful situation (caging transition) compared to peer-reared (Clarke, Reference Clarke1993); the peer-reared monkeys were physiologically less responsive to this stressful situation, possibly showing an inappropriate response to a stressful situation compared to mother-reared monkeys, underscoring the considerable influence of mothers on their infants’ physiological regulation of stress. Additionally, there are also differences based on rearing condition among those not provided maternal care. For instance, surrogate-peer reared (which combines peer-rearing and a surrogate mother) macaques engage in more foraging behavior, more environment exploration, and less partner clinging than peer-reared infants (Brunelli et al., Reference Brunelli, Blake, Willits, Rommeck and McCowan2014). These studies provide evidence of a range of adverse outcomes in nonhuman primate infants that are not mother-reared, however, provision of some caregiving (e.g., peer-reared vs. surrogate/isolation) may represent an intermediate level of support on a continuum.

Human evolution

There are several species-specific features of humans, compared to living nonhuman primate species, that likely contribute to unique patterns of proximity between children and their adult caregivers. Human evolution involved several critical changes in body architecture, of which both pelvic changes associated with bipedalism and increases in brain size had consequences for early interactions between parents and offspring (Wall-Scheffler et al., Reference Wall-Scheffler, Geiger and Steudel-Numbers2007). The relatively larger adult human brain combined with pelvic changes resulted in an evolutionary compromise, necessitating smaller and less mature brains at birth (Trevathan & McKenna, Reference Trevathan and McKenna1994). Human infants are born with only 25% of their brain volume compared to 45% in chimpanzees (Fernandes & Woodley of Menie, Reference Fernandes2017; Trevathan & McKenna, Reference Trevathan and McKenna1994). As a result, newborn human infants, relative to other species, are more vulnerable at birth and reliant on caregivers for an extended period of time for their survival. The evolution of fur-clinging or infant carrying across species enables the close physical support required for survival. For example, in nonhuman primates, fur-clinging has evolved several times independently, suggesting the evolutionary advantage of the infant being physically attached to its mother (Klopfer & Boskoff, Reference Klopfer, Boskoff and Doyle1979; Nakamichi & Yamada, Reference Nakamichi and Yamada2009). In humans, adult carrying of infants may have emerged in relation to the gradual decrease in human body hair over the course of evolution (which prevents fur clinging) along with less developed motor skills at birth in human infants (Amaral, Reference Amaral2008; do Amaral, Reference do Amaral1989).

Compared to practices such as infant parking, infant carrying has high energetic cost but has been used throughout human evolutionary history (Ross, Reference Ross2001), indicating evolutionary advantages which recompense for the energetic expenditure (Berecz et al., Reference Berecz, Cyrille, Casselbrant, Oleksak and Norholt2020). These advantages include reduced crying, body movement, and heart rate in infants while being carried, a phenomenon also seen in most mammalian species known as the mammalian transport response (Esposito et al., Reference Esposito, Yoshida, Ohnishi, Tsuneoka, del Carmen Rostagno, Yokota and Kuroda2013). Close proximity aids other important components of human infant caregiving including feeding (Anderson & Starkweather, Reference Anderson and Starkweather2017). For example, in addition to breastfeeding, which requires proximity, the relatively late age at which permanent molar teeth develop in human children means that they are highly dependent upon caregivers for processing food to ease digestion (Sellen, Reference Sellen2007). In summary, human evolution led to greater offspring vulnerability in early life, relative to other primate species. The need for adults to feed, protect, and soothe children requires prolonged proximate caregiving throughout infancy and early childhood (Pavard et al., Reference Pavard, Koons and Heyer2007).

Infant development

As infants (age <12 months) develop, their relationship with their caregiver changes. As noted above, the presence of a caregiver is a species-expected feature of human infancy. Physical touch is a prominent component of early caregiver–infant interaction from birth and is believed to be fundamental to how children explore and interact with their environment (Gallace, Reference Gallace2012). Affective interpersonal touch, specifically slow, gentle touch (e.g., a hug or caress) likely promotes social and cognitive competencies in early development (Fairhurst et al., Reference Fairhurst, Löken and Grossmann2014; Tuulari et al., Reference Tuulari, Scheinin, Lehtola, Merisaari, Saunavaara, Parkkola and Björnsdotter2019; Walker & McGlone, Reference Walker and McGlone2013), including secure attachments (Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Perry, Sloan, Kleinhaus and Burtchen2011). Attachment theory asserts that a behavioral system has evolved to keep infants close to their caregivers and safe from harm; a central tenet is that young children require a close relationship with a primary caregiver for social and emotional development (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1969). The attachment system is foundational for promoting survival of young infants, in part due to increased proximity to the caregiver, which better allows for infants’ needs to be met. The relationships developed over frequent, regular interactions marked by caregiving that predictably meets infant needs are the foundation of attachment relationships. Attachment representations are characterized by expectations of the attachment figure as a source of support, and care, and early experiences with parental care guide children’s proximity seeking behavior (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1973). In particular, attachments are characterized by two classes of behaviors: attachment behaviors and exploratory behaviors (Ainsworth & Bell, Reference Ainsworth and Bell1970), both of which have clear implications for proximity.

Attachment behaviors reflect physical closeness between caregivers and children, including proximity seeking behaviors. Exploratory behaviors reflect children’s comfort leaving the attachment figure to explore the environment. In part, the comfort to leave the caregiver is facilitated by the child knowing that the caregiver will be within close proximity should threat emerge in the child’s environment (i.e., should the attachment system be activated). Attachment theorists have used the “circle of security” to characterize caregiver–child proximity patterns (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Cooper, Hoffman and Marvin2013). In this, caregivers serve as a secure base where children feel confident in exploring their environment because they trust that their caregiver will be able to provide a “safe haven” in times of need. During this environmental exploration, infants “check in” with their caregivers by either moving physically closer to them periodically or by visually checking in. In these interactions, uncertainty about the environment may prompt children to check in and danger triggers the drive to seek safety and close proximity to the caregiver.

Changes in caregiver–child proximity across developmental stages

Caregiver–child interactions, including the type of contact (e.g., gentle touch, infant carrying) and amount of time in close proximity, change dramatically over the course of the first months and years of life. The specific competencies of the developing child may be a central driver of this change. At birth, newborn infants are wholly dependent on their caregivers to meet all of their basic physical needs. Their frequent feeding and diaper changes require continual monitoring and physical touch by their caregiver. Infant crying changes drastically over the first few months of life, peaking at, on average, 3 hr of crying per day when infants are around 6 weeks of age, and steadily declining to about 1 hr per day by the time infants reach 12 weeks (Kurth et al., Reference Kurth, Kennedy, Spichiger, Hösli and Zemp Stutz2011). In many cases, infant crying is primarily soothed by actions that require touch, whether that is feeding, removal of wet or soiled diapers or clothing, or being held and rocked. Especially during early stages of development, touch is a primary source of communication, conveying different meanings through the duration, velocity, and frequency of physical contact (Hertenstein, Reference Hertenstein2002; Kirsch et al., Reference Kirsch, Krahé, Blom, Crucianelli, Moro, Jenkinson and Fotopoulou2018). Caregiver playful touch has been shown to increase infant positive affect (Egmose et al., Reference Egmose, Cordes, Smith-Nielsen, Væver and Køppe2018) and to calm infants in pain or discomfort (Bellieni et al., Reference Bellieni, Cordelli, Marchi, Ceccarelli, Perrone, Maffei and Buonocore2007). During early infancy (i.e., ages 0–3 months), infants do not discriminate between caregivers or show strong preferences for one caregiver over another (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978). However, this begins to change from 4 to 5 months of age as infants show preferences for familiar caregivers. At this age, infants visually seek out their caregivers and may get restless and exude cues (e.g., cooing, fussing) in order to acheive proximity with familiar and preferred caregivers (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978; Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1982).

Additionally, caregivers define the structure of infants’ physical environment through the wearing or physical placement of infants (e.g., what toys are available, amount of infant access). For example, childrearing practices involving touch impact the trajectory and timing of sitting; earlier independent sitting (e.g., by 5 months) is associated with caregiver exercise and massage of their infants (Karasik et al., Reference Karasik, Tamis-LeMonda, Adolph and Bornstein2015). Further, infants appear to walk sooner if mothers deliberately exercise upright skills (e.g., holding and allowing upright positioning, leg and foot movement) as part of a daily routine, compared to infants not exposed to this exercise (Hopkins & Westra, Reference Hopkins and Westra1990). Similarly, comparing an exercise intervention group (parents instructed to provide stepping or sitting exercises to infants) to a control group (no exercise instructions), infants in the experimental group stepped more and sat upright for longer after 7 weeks of the intervention (Zelazo et al., Reference Zelazo, Zelazo, Cohen and Zelazo1993). In turn, the development of motor skills, such as sitting up or standing independently, as well as the onset of independent ambulation, affect the access children have to their environment by providing new or increased opportunities for interacting with objects and learning (Adolph & Franchak, Reference Adolph and Franchak2017). Further, as infants gain locomotive skills, mothers no longer need to provide constant assistance during interactions, allowing infants to engage in greater self-directed behaviors (Thurman & Corbetta, Reference Thurman and Corbetta2017). When infants begin crawling, or other independent movement (e.g., scooting or creeping), they gain more control over their location and engage in more object and environmental exploration (see Campos et al. [Reference Campos, Anderson, Barbu-Roth, Hubbard, Hertenstein and Witherington2000] for a review) involving traveling greater distances from their mother, though mothers tend to remain within a close distance (e.g., within arm’s reach) to supervise and provide support as their infants became experienced crawlers (Thurman & Corbetta, Reference Thurman and Corbetta2017). As infants reach ages 7–12 months, in addition to the development of independent ambulation (e.g., crawling and scooting), stranger weariness also emerges. Rather than just exhibiting restlessness in response to caregiver absence, infants actively seek out touch and proximity of familiar caregivers (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978; Tracy & Ainsworth, Reference Tracy and Ainsworth1981), often clinging to familiar caregivers in the presence of unfamiliar people.

Around 11–12 months, clear-cut attachment to one or more caregivers is evident. Ainsworth et al. (Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978), building upon Bowlby’s theory of attachment (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1969), introduced the Strange Situation Procedure, a series of separation and reunion episodes between the caregiver and infant, which helped to characterize patterns of behavior that reflect caregiver–child attachment classifications. The majority of infant–caregiver dyads (an estimated 60% [Moullin et al., Reference Moullin, Waldfogel and Washbrook2014] of epidemiological samples of dyads in the U.S.) display patterns of secure attachments, such that the infant exhibits distress when their caregiver leaves as well as calms quickly after being reunited with the caregiver. A recent study reported that 25% of dyads are characterized as insecurely attached (i.e., insecure-resistant or insecure-avoidant classifications; Moullin et al., Reference Moullin, Waldfogel and Washbrook2014). Dyads who are classified as insecure-resistant typically display behaviors that reflect infant anger at caregivers for leaving. These infants seek proximity with their caregivers upon reunion (e.g., asking to be held), but may also push their caregiver away while being held (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978). Dyads classified as insecure-avoidant are characterized by infants who appear not distressed by the caregiver’s departure and who do not seek proximity with their caregivers during the reunion (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978). Patterns of proximity seeking are, in fact, a necessary component to making attachment classifications; though the quality of interactions during times of close proximity are also salient for forming attachment classifications.

Proximity changes associated with locomotion in children

As children transition to walking, they have even greater autonomy regarding their physical location, enabling frequent arrivals and departures from their caregiver. Walkers move more, play more, and interact more with mothers than do crawlers, and walkers travel three times the distance of crawlers (Karasik et al., Reference Karasik, Tamis-Lemonda and Adolph2014). The ability to walk both increases the distance (how far away) between child and mother while also changing their interactions (Karasik et al., Reference Karasik, Tamis-Lemonda and Adolph2011, Reference Karasik, Tamis-Lemonda and Adolph2014). Walking infants engage in more interactive bids with toys and mothers (Clearfield, Reference Clearfield2011; Clearfield et al., Reference Clearfield, Osborne and Mullen2008; Karasik et al., Reference Karasik, Tamis-Lemonda and Adolph2011), as well as explore their environments further. These moving bids are more likely to get a response from the parent and promote interaction between parent (mother or father) and infant (Walle, Reference Walle2016). Further, child-initiated separations and reunions provide opportunities to activate the attachment system. Children who feel secure in exploring their environment may physically check-in with their caregiver who is close in proximity. Over time, the distance between children and their caregiver tends to increase (Karasik et al., Reference Karasik, Tamis-Lemonda and Adolph2011, Reference Karasik, Tamis-Lemonda and Adolph2014) and time spent apart or in independent activity increases (Melson & Kim, Reference Melson and Kim1990). Thus, the developmental transition to walking requires a change in the pattern of proximity, as caregivers are tasked with engaging in new ways with their infant while maintaining supervision (and therefore some degree of physical closeness).

Although physical touch has been found to decrease as infants gain the ability of independent locomotion (Ferber et al., Reference Ferber, Feldman and Makhoul2008), children and mothers interact more through gaze, vocalizations, and bids for attention, all requiring continued proximity, even as close physical contact decreases (Clearfield, Reference Clearfield2011; Karasik et al., Reference Karasik, Tamis-Lemonda and Adolph2011, Reference Karasik, Tamis-Lemonda and Adolph2014). For example, as their children begin to walk, mothers are observed to engage in increased labeling, gesturing, and use of action words (Olson & Masur, Reference Olson and Masur2011; Tamis-LeMonda et al., Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Adolph, Dimitropoulou and Zack2007). As noted by a review of parental supervision and child risk of injury, caregivers who provide direct attention (visual and auditory), stay within reach of the child and maintain this attention and distance (e.g., provide these continually) are most likely to ensure child safety (Petrass et al., Reference Petrass, Blitvich and Finch2009). In summary, the nature of proximity and contact between mother and child in early development changes substantially with the acquisition of independent ambulation, with a significant impact on caregiver–infant interactions. Assessing how children gain independence (e.g., whether children initiate more and longer separations from their caregivers vs. whether parents initiate fewer reunions) both across time and between families may be helpful for understanding the link between changes in independent exploration and increases in experience-dependent learning.

Potential predictors of proximity

While there appear to be universal aspects of human infancy and the caregiving behaviors required to survive, children’s experiences vary widely. Caregiver–child proximity patterns are likely influenced by a wide range of environmental, societal, cultural, and personal influences. Here we focus on a few specific areas to provide examples of how these may impact or shape proximity, specifically, we discuss parenting across cultures, parental leave, and maternal psychopathology (specifically depression) in relation to caregiver–child proximity. We provide details (see Table 2) regarding the method of proximity measurement and definition used from a representative sample of studies related to predictors of proximity, including what outcomes or constructs were investigated in relation to proximity.

Table 2. Examples from literature investigating predictors of caregiver–child proximity

Cultural differences related to proximity

Culture (i.e., a pattern of beliefs and behaviors that are shared by a group of people that serve to regulate their daily living; Bornstein, Reference Bornstein2012) influences caregiver cognitions that in turn shape caregiving practices (Harkness et al., Reference Harkness, Super, Moscardino, Rha, Blom, Huitron and Palacios2007). Patterns of childrearing reflect adaptations to the society’s specific setting, needs, and beliefs (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein2012). Furthermore, practical (e.g., availability of infant equipment [bouncers; exersaucers]; Maudlin et al., Reference Maudlin, Sandlin and Thaller2012) and policy differences across and within countries (e.g., availability of paid parental leave or access to affordable, high-quality childcare; Bornstein, Reference Bornstein2012; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Hyde, Essex and Klein1997; Gaias et al., Reference Gaias, Räikkönen, Komsi, Gartstein, Fisher and Putnam2012) also impact parenting practices, influencing the amount of time and types of interactions that occur in close child and caregiver proximity.

Cultural variation in infant carrying

One area in which cultural variation has been well-studied is in relation to infant carrying, and the influence of carrying decisions on close physical contact between infants and their caregivers. Although there are variations within cultures, in Western societies, infants are estimated to experience close physical contact with caregivers for approximately 2 hr of the day (Dotti Sani & Treas, Reference Dotti Sani and Treas2016). In many non-Western cultures, infants have close physical contact with caregivers for the majority of their day (Hewlett & Lamb, Reference Hewlett, Lamb, Keller, Poortinga and Schölmerich2009), specifically through long durations of caregivers carrying their infant on their body. This has been seen in many parts of Africa (Hewlett et al., Reference Hewlett, Lamb, Shannon, Leyendecker and Schölmerich1998), Asia (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Wang2017), and Central and South America (Conklin & Morgan, Reference Conklin and Morgan1996; Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Coulombe, Moss, Rieger, Aragón, MacLean and Handal2016). For example, in Ghanaian culture, mothers wrap their infants onto their backs for most of the day (Kärtner et al., Reference Kärtner, Keller, Lamm, Abels, Yovsi, Chaudhary and Su2008; Keller et al., Reference Keller, Yovsi, Borke, Kärtner, Jensen and Papaligoura2004; Owusu-Ansah et al., Reference Owusu-Ansah, Bigelow and Power2019); whereas other cultural practices involve carrying infants in slings, strapped to the front of the caregiver’s body, including both forward and caregiver-facing positioning (Russell, Reference Russell2014). The degree of early contact between mother and child is likely important to child outcomes, attachment styles, and caregiver–child relationships. For example, more close, physical contact between mother and child has been prospectively linked to secure attachment relationships (Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Wilson, Hertenstein and Campos2000).

Equipment use and caregiver–child proximity

Furthermore, infant care methods and use of infant equipment in Western societies may help to explain the reduced time caregivers are in close physical contact with their infants relative to non-Western societies. For example, differences may arise from sleeping practices (reduced use of co-sleeping, i.e., not sharing a bed with caregiver) or infant care methods that are more prevalent in Western societies such as feeding of infant formula and use of infant equipment (Bigelow & Williams, Reference Bigelow and Williams2020), which may reduce physical contact between parent and child. Studies have reported widespread use of infant equipment, for example, both at home and in childcare settings in the U.S. (Fay et al., Reference Fay, Hall, Murray, Saatdjian and Vohwinkel2006; Hallam et al., Reference Hallam, Bargreen, Fouts, Lessard and Skrobot2018; Siddicky et al., Reference Siddicky, Bumpass, Krishnan, Tackett, McCarthy and Mannen2020). Use of bouncers, car seats, and infant swings can help to soothe and entertain children as well as allow caregivers to engage in other tasks (e.g., cooking, showering), thus providing a safe and convenient way for caregivers to continue daily activities made more difficult while holding or wearing an infant. However, such equipment increases distal forms of interaction between infants and mothers (e.g., vocalizations, expressions; Keller et al., Reference Keller, Borke, Staufenbiel, Yovsi, Abels, Papaligoura and Su2009) and limits physical closeness (Little et al., Reference Little, Legare and Carver2019; Maudlin et al., Reference Maudlin, Sandlin and Thaller2012), with implications for caregiver–child interactions. For example, a study of 23 4–12-month-old infants and mothers found that mothers were more responsive to their infants’ cues when they were worn on mother’s body than placed in a seating device (Little et al., Reference Little, Legare and Carver2019). Thus, the use of infant equipment (more prevalent in Western cultures) likely impacts a range of caregiver–child interactions, including the amount of time spent in close proximity (both in terms of close physical contact and physical distance).

Cultural goals and caregiver–child interactions

Cultural goals related to desired developmental outcomes may additionally influence variation in interaction styles between caregivers and infants (Keller et al., Reference Keller, Yovsi, Borke, Kärtner, Jensen and Papaligoura2004). Western cultures tend to encourage autonomy and independence, with caregiver–infant proximity characterized by parents often engaging in frequent verbal and face-to-face interactions with their infants. This style differs from parents in non-Western cultures, who tend to value social sensitivity and interconnectedness, where caregiver–child interactions are characterized by close physical contact and affective tuning between parents and infants (Tronick et al., Reference Tronick, Morelli and Winn1987). Keller et al. (Reference Keller, Borke, Staufenbiel, Yovsi, Abels, Papaligoura and Su2009) investigated cultural models and parenting styles across three groups: finding that urban, middle-class families from Western communities (Euro-American, German and Greek; representing a cultural model of independence) practice more distal parenting styles, rural farming families with less formal education (Cameroonian and Indian; representing an interdependent cultural model) practice more proximal parenting, and non-Western urban families in communities that prioritize relatedness (Costa Rican, Chinese, and Indian; representing the model of autonomous relatedness) express a combination of distal and proximal styles (for further detail see Keller et al., Reference Keller, Borke, Staufenbiel, Yovsi, Abels, Papaligoura and Su2009). Importantly, patterns of caregiving practices were not homogenous within cultures as individual characteristics, beliefs, and parenting goals impact caregiver–child proximity within cultural groups. These differences in proximal versus distal caregiving behaviors are associated with differences in developmental outcomes. Infants exposed to more proximal caretaking have demonstrated early development of compliance and obedience as toddlers, whereas distal caretaking was associated with earlier development of self-recognition (Keller et al., Reference Keller, Yovsi, Borke, Kärtner, Jensen and Papaligoura2004). Multiple studies have similarly found differences in caretaking behavior when comparing distinct cultural groups, noting that German and American mothers respond to their infants primarily through vocalizations and facial expressions whereas Cameroonian, Japanese, and Kenyan mothers engage through physical touch and closeness with their infants (i.e., patting, kissing, hugging; Fogel et al., Reference Fogel, Toda and Kawai1988; Kärtner et al., Reference Kärtner, Keller, Lamm, Abels, Yovsi, Chaudhary and Su2008, Reference Kärtner, Keller and Yovsi2010; Richman et al., Reference Richman, Miller and LeVine1992). These differences in caregiving behaviors by cultural group may reflect cultural goals for infant development and norms within cultures, with implications for patterns of caregiver–child proximity.

Notably, even when comparing geographically similar cultural groups, distinct differences can be found in the infants’ early care environment, often based on necessity or cultural practices (e.g., hunting communities will engage in more infant carrying because they are moving more frequently and over greater distances than in a farming community where infants can be left stationary within the caregiver’s visual field). For example, when comparing African tribes from similar settings, caregiver–infant interactions in the Aka cultural group (hunter gatherers) are characterized by close caregiver–infant proximity through infant carrying, frequent feeding, and proximal touch (Hewlett et al., Reference Hewlett, Lamb, Shannon, Leyendecker and Schölmerich1998). The Ngandu (farmers) infants tend to experience less physical touch and were picked up and held at approximately half the rate of Aka infants, but experienced more distal communication, such as smiles and vocalizations with their caregivers (Hewlett et al., Reference Hewlett, Lamb, Shannon, Leyendecker and Schölmerich1998). Thus, although there are universal infant needs that dictate broad caregiving behavior (e.g., providing safety and nourishment) there are a wide range of behaviors that differ both within and across cultural groups, which are relevant to understanding differences in caregiver–child proximity.

Policies related to caregivers

Cultural expectations and state supported opportunities for parental leave and childcare are also associated with patterns of caregiver–child proximity. Policies associated with opportunities for parental leave and childcare are often closely tied to and interrelated with cultural norms and expectations. Attitudes can both inform and reflect policy (Manza & Cook, Reference Manza and Cook2002). For example, paternity leave and longer periods of maternity leave are found in countries where expectations about division of childcare labor are more equitable (Li et al., Reference Li, Knoester and Petts2021). Similarly, where incentives are offered for fathers to take paternity leave, a greater proportion do, which has been linked to more equitable domestic labor between mothers and fathers (Craig & Mullan, Reference Craig and Mullan2010). Among high income countries, the U.S. is unique in reduced likelihood of paid parental leave, offering less time off, and fewer federal policies in place that support new mothers (e.g., guaranteed paid leave, shorter periods of leave) than other industrialized countries (Plotka & Busch-Rossnagel, Reference Plotka and Busch-Rossnagel2018). In Finland, for example, government programs offer options of federally subsidized day cares and both maternity and paternity leave, and 99% of all Finnish children are cared for at home by their parents for their first year of life, dropping to 40% at age five (Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, 2006). In the U.S., 53% of children under 1 year of age are cared for at home by their parents, dropping down to 27% for children aged 1–5 years (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2019). The provision of relatively long maternity and paternity leave supports a home environment where infants have the opportunity to engage in close proximity to both parents, instead of primarily the mother, as is the norm in many countries (Flacking et al., Reference Flacking, Dykes and Ewald2010; Gaias et al., Reference Gaias, Räikkönen, Komsi, Gartstein, Fisher and Putnam2012). Only approximately half of all countries make any leave available to fathers, and the majority provide less than 3 weeks (Heymann et al., Reference Heymann, Sprague, Nandi, Earle, Batra, Schickedanz and Raub2017). Gender disparities in paid parental leave may reinforce the idea that women are primarily responsible for caregiving and studies have shown that fathers who take paid leave are more involved in childcare, not only during that leave, but later in the child’s life, which may in turn influence cultural and gender norms of proximity between each caregiver and the child (Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, Reference Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel2007; O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2009). Public policies regarding paid parental leave can therefore either facilitate or hinder the availability of one or both parents to spend time at home with their children in early life. Such policies, related to and influenced by cultural norms about caregiving and gender roles, plausibly impact the potential for physical proximity and the quantity of time caregivers and infants spend together.

Maternal depression

Importantly, there are individual differences based on maternal or child characteristics that impact how caregivers or children may elicit or respond to proximity and touching behaviors. Here we focus on exploring these in relation to maternal depression. Major depressive disorder is a common psychological disorder characterized by mood, cognitive, and physical symptoms over at least a 2-week period (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The lifetime prevalence of depression is approximately 8% of American adults (Brody et al., Reference Brody, Pratt and Hughes2018); in a given year, 7.5 million adults living with children suffer from depression and an estimated 15 million children live in households with parents experiencing major or severe depression (National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Depression, Reference Nakamichi and Yamada2009). One of the proposed mechanisms linking parental depression to more negative child outcomes is through caregiving behaviors (Gotlib et al., Reference Gotlib, Goodman and Humphreys2020), including altered tactile interactions. Previous research has indicated that mothers with depression exhibit more negative caregiving behavior (e.g., intrusive or withdrawn) and less positive caregiving behavior (e.g., responsive or sensitive; Field, Reference Field2010; Forman et al., Reference Forman, O’Hara, Stuart, Gorman, Larsen and Coy2007; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Halligan, Goodyer and Herbert2010). Further, mothers with depression appear to touch their infants less often and with less affection (Ferber et al., Reference Ferber, Feldman and Makhoul2008) as well as engage in more rough touching (e.g., poking, tickling, rough pulling; Malphurs et al., Reference Malphurs, Raag, Field, Pickens and Pelaez-Nogueras1996) compared to mothers without depression. However, there is heterogeneity of touching styles in mothers with depression, as not all mothers with depression engage in over-stimulating or intrusive touch (Mantis et al., Reference Mantis, Mercuri, Stack and Field2019). Different patterns of infant touch can also be seen from mothers who experience subclinical, transitional depressive symptoms following childbirth (e.g., “baby blues”). These mothers have been shown to give less stimulating and affectionate touch to their infants (Ferber, Reference Ferber2004). Infants of mothers with depression tend to touch themselves more often, perhaps compensating for a lack of touch or the more negative touch behaviors from their mother (Hentel, Reference Hentel2000; Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Reissland and Shepherd2004). These differences in caregiving interactions, specifically seen through altered tactile relationships between mothers with depression and their infants, illustrate the potential impact individual differences (e.g., depression) may have on caregiver–child proximity.

Though we only focus on specific illustrative examples, caregiving practices related to caregiver–child proximity (e.g., carrying behavior, touch, interaction style) are influenced by a wide range of societal, cultural, and individual differences.

Outcomes related to proximity

Specific developmental experiences related to caregiver–child proximity, such as nurturing touch, or secure, physically close relationships, or conversely, absent or neglectful caregiving relationships, have implications for child functioning. Here we briefly review child outcomes associated with characteristics of caregiver touch (e.g., type and frequency), use of infant equipment, child separations from a caregiver, and children in institutional care to describe the adaptive and maladaptive outcomes related to specific experiences of proximity (or deprivation) in caregiver–child relationships. In Table 3, we provide details of a subset of illustrative studies investigating proximity and child outcomes, specifically how proximity was operationalized, age of assessment and the main findings.

Table 3. Examples from literature investigating caregiver–child proximity and child outcomes

Touch

The benefits of touch for a child’s development have been demonstrated in multiple research studies (see Table 3, which highlights specific examples, including methods used to operationalize proximity). The type of touch (e.g., massage or soothing touch and low versus moderate pressure) and frequency of touch between caregivers and children are differentially associated with child outcomes indicating that specific characteristics of touch, and not merely the act of touching, are significant. For example, low-weight infants who received moderate pressure touch compared to low pressure touch gained more weight (Field et al., Reference Field, Diego, Hernandez-Reif, Deeds and Figuereido2006). Similarly, massage therapy appears to impact a range of physiological and biological processes and has been linked to improved growth and development in preterm infants, decreases in stress hormones, and increased immune function following massage (see review by Field et al., Reference Field, Diego and Hernandez-Reif2010). Additionally, frequency of touch appears to be important and has been linked to exploration behavior, language development and brain structure. For example, a study comparing a high and low touch group, found that infants who experienced more frequent touch, specifically affectionate touch were more likely to engage in object exploration and to socially engage with strangers (Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Kanakogi and Myowa2021). Another study found that infant vocabulary word learning appeared to be facilitated when words were paired with caregiver touch (Seidl et al., Reference Seidl, Tincoff, Baker and Cristia2014). Finally, in a study of 5-year-olds, frequency of maternal touch during a maternal–child interaction was associated with stronger connectivity of the posterior superior temporal sulcus and other nodes in the social brain (Brauer et al., Reference Brauer, Xiao, Poulain, Friederici and Schirmer2016). Touch is not only a critical means of communicating openness, engagement, and warmth (Oveis et al., Reference Oveis, Gruber, Keltner, Stamper and Boyce2009), type and frequency of touch appear to be important for child physical and emotional development. For an in-depth discussion of touch, see reviews by Cascio et al. (Reference Cascio, Moore and McGlone2019) and Blackwell (Reference Blackwell2000).

Use of infant equipment

Use of infant equipment (e.g., bouncers, car seats, and infant swings), provides a convenient way for caregivers to engage in other activities, while keeping their child entertained and safe. Widespread use of these devices has been reported, particularly in Western settings such as the U.S. (Fay et al., Reference Fay, Hall, Murray, Saatdjian and Vohwinkel2006; Hallam et al., Reference Hallam, Bargreen, Fouts, Lessard and Skrobot2018; Siddicky et al., Reference Siddicky, Bumpass, Krishnan, Tackett, McCarthy and Mannen2020), with implications for caregiver–child proximity, both increasing distance and duration of time spent apart (Little et al., Reference Little, Legare and Carver2019; Maudlin et al., Reference Maudlin, Sandlin and Thaller2012). The relative increase in the availability and use of infant holding devices or equipment (e.g., bouncers, highchairs) may impact rates of baby carrying/wearing in Western settings, with potential implications for attachment. A small, randomized trial of women provided either infant carriers (n = 23) or plastic seats (n = 26) found late differential rates of relationships classified as secure by the time infants were 1 year old (83% vs. 38%; [Anisfeld et al., Reference Anisfeld, Casper, Nozyce and Cunningham1990]); the same study found that baby carrying was associated with less solo vocalizations and periods of crying, as well as later social smiling behaviors. The degree of early contact (i.e., amount of affectionate touch during feeding) between mother and infant is prospectively linked to secure attachment relationships (Bigelow & Williams, Reference Bigelow and Williams2020; Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Wilson, Hertenstein and Campos2000). Foundational to secure attachment is a physically close caregiver–child relationship, allowing for caregiver responsiveness to infant cues, for a caregiver that predictably meets their infant’s needs, for moderation of infant distress, and the provision of a secure base.

Caregiver–child separation

A recent review of caregiver–child separations (e.g., forced separation due to war, parent emigration for economic opportunities, parent death) highlights a link between child separation from their caregiver and a range of negative consequences, including cognitive, social-emotional, and mental health domains (Waddoups et al., Reference Waddoups, Yoshikawa and Strouf2019). Multiple studies have investigated type of separation (e.g., voluntary as in migration for work or where related to traumatic experiences for the child) and associated child outcomes (Waddoups et al., Reference Waddoups, Yoshikawa and Strouf2019). Outcomes experienced from differing experiences of separation may vary based on several factors, including the context of the separation (see Humphreys, Reference Humphreys2019 for review). Differing factors that can influence related outcomes for the child include the length of separation (Loman et al., Reference Loman, Wiik, Frenn, Pollak and Gunnar2009), the nature of the family structure post separation, and the availability of an alternative reliable caregiver (Wiese & Burhorst, Reference Wiese and Burhorst2007), if the separation was voluntary (Valtolina & Colombo, Reference Valtolina and Colombo2012; Venta et al., Reference Venta, Bailey, Mercado and Colunga-Rodríguez2021), and whether the separation is accompanied by a separate trauma (Bouza et al., Reference Bouza, Camacho-Thompson, Carlo, Franco, Coll, Halgunseth and White2018; Waddoups et al., Reference Waddoups, Yoshikawa and Strouf2019). For a detailed review of type of caregiver–child separation and associated outcomes, see Waddoups et al. (Reference Waddoups, Yoshikawa and Strouf2019).

Child outcomes associated with institutional care

Children raised in institutional settings, specifically where caregiving and associated physical touch and responsive interactions are limited (Smyke et al., Reference Smyke, Dumitrescu and Zeanah2002), have exhibited higher risk for behavioral, emotional, and social problems (van IJzendoorn et al., Reference van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Duschinsky, Fox, Goldman, Gunnar and Sonuga-Barke2020). While myriad negative outcomes are associated with exposure to institutional care, it is the lack of responsive care from a dedicated adult that is believed to be the primary cause of poor outcomes following orphanage care. Furthermore, while rates of psychiatric disorders are higher among those with any exposure, and prolonged exposure, to institutional care (Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Gleason, Drury, Miron, Nelson, Fox and Zeanah2015; Zeanah et al., Reference Zeanah, Smyke and Settles2008), children in institutional care are at particularly increased risk for disorders of disturbed relatedness (including reactive attachment disorder [RAD] and disinhibited social engagement disorder [DSED]; Guyon-Harris et al., Reference Guyon-Harris, Humphreys, Degnan, Fox, Nelson and Zeanah2019; Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Nelson, Fox and Zeanah2017; Zeanah & Gleason, Reference Zeanah and Gleason2015).

Notably, a diagnosis of RAD is characterized by a departure from expected patterns of proximity seeking; children with RAD do not seek out or accept comfort when it is provided (Zeanah & Smyke, Reference Zeanah and Smyke2008). A diagnosis of RAD requires insufficient care in early life, making it one of the few disorders with a known environmental etiology (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). For DSED, patterns of proximity seeking are also altered, though children with DSED seek out close contact with unfamiliar adults (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); some have termed this behavior “indiscriminate friendliness” (e.g., Chisholm, Reference Chisholm1998). The neurobiological correlates of DSED are not well-known, though some speculate that increased proximity seeking with adults is adaptive when children have no strong primary relationships (Zeanah & Gleason, Reference Zeanah and Gleason2015). These outcomes are rare and are only found among children without access to a regular and at least somewhat responsive adult caregiver, leading to calls to promote children’s resilience to adversity by first prioritizing family placements and ensuring that caregivers are consistently available (Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, King, Guyon-Harris and Zeanah2021).

Summary of cross-disciplinary research

In summary, in the above review of caregiver–child proximity literature we aimed to discuss methods of characterizing caregiver–child proximity, predictors and outcomes of these patterns, and extant research related to caregiver–child proximity across disciplines. Across primate species and human evolutionary history, close contact between infants and caregivers is species-expected and required for survival, nurturance, and stimulation. In many primate species, mothers maintain close and continuous contact with their infant offspring to ensure survival. Studies of primate infant separations from their mothers have shown increased physiological markers of stress, behavior indicative of depression or despair and underscore the crucial biological need for the infant to maintain close contact with its mother. Though, similar to patterns in human caregiver–child proximity, physical distance between primate caregivers and their offspring increases with maturation as offspring become more independent.

As an altricial species, human infants are uniquely dependent on caregivers for feeding, nurturance, and safety, requiring a prolonged close physical relationship for longer periods of time compared to nonhuman primate infants, from birth and lasting for several years. Further, multiple caregiver behaviors related to proximity with their child (e.g., affectionate touch, provision of a secure base, soothing) are believed to be essential components for adaptive child functioning. Changes in caregiver–child proximity are both dependent on child developmental stage (e.g., increased distance between caregiver and child as children begin to crawl or walk) as well as help to mold developmental outcomes (e.g., increased autonomy in children of parents who practice more distal caretaking). Importantly, multiple studies have investigated variations in caregiver–child proximity (e.g., affectionate versus rough touch, distal versus proximal caretaking, infant carrying, children raised with or without a dedicated caregiver); these variations in caregiving have been shown to significantly impact child adaptive and maladaptive outcomes. More work is needed to better characterize these variations in care and understand how these may be situated within a dimensional framework as well as when and how aspects of proximity in caregiver–child relationships impact children.

Caregiver–child proximity within dimensional frameworks

Dimensional models of early experience, which consider children’s environments along dimensions of severity (i.e., low to high), provide a useful framework to understand the importance of characterizing children’s early environments along a continuum. For example, the DMAP (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan and Lambert2014), which focuses on threat and deprivation, has clear relevance to studies that have investigated children in institutional care. The devastating impact of deprivation (e.g., lack of a consistent, nurturing caregiver) can clearly be seen in studies of children in institutionalized care. Less clear is how (and at what point) features of caregiver–child proximity in relatively more typical contexts (e.g., within caregiver–child relationships where depression impacts touch) may be representative of deprived care and when this may impact child outcomes. The interactions that occur between children and their caregivers that are essential for typical and healthy development all occur when children and caregivers are within close proximity of each other (e.g., at least some level of responsive interactions; physical soothing when distressed). Thus, when caregivers and children are infrequently in close proximity, this may represent deprived care, though much work is needed to understand at what point infrequent proximity may impact the child and how. One approach to capturing the complexity of experience–outcome associations is described in the neglect–enrichment continuum (Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, King, Gotlib and Zeanah2018; King et al., Reference King, Humphreys and Gotlib2019), where the association between more input and healthy development may plausibly take on several forms. For example, consider the input of nurturing touch by a caregiver. Three potential models on the relationship between this form of touch and healthy or adaptive development include: (1) the threshold model, (2) linear model, and (3) diminishing returns model.

First, the threshold model is a binary characterization of caregiving as either neglectful or not neglectful, perhaps consistent with the “good enough” parent (Winnicott, Reference Winnicott2002) perspective, and that children likely will have different outcomes, whether they received enough (or not) nurturing touch. Second, the linear model is characterized by a steady, linear trajectory between enrichment and healthy development. In this model, children are expected to benefit from experiencing greater amounts of nurturing touch, and that the benefits of more touch would be equivalent across the full range of experience. Third, the diminishing returns model proposes that the association between environmental enrichment and children’s healthy development is nonlinear, and changes based on the level of enrichment. Specifically, on the lower end of the continuum (i.e., greater deprivation), the association between environmental enrichment and healthy development is the steepest such that the per increment gain in developmental outcomes from increases nurturing touch would be more substantial than the same amount of change in nurturing touch at the higher (i.e., more enriched) end of the continuum. These models provide a useful theoretical framework to consider how experience–outcome associations may be characterized to better understand the influences of early experiences on child outcomes.

Given the broad ways in which proximity can be characterized, understanding critical points along the continuum is paramount to inform how (and when) proximity may adversely impact child outcomes. Further, how this continuum may translate to child functioning remains far from clear and may differ based on the operationalization of caregiver–child proximity. Perhaps due to difficulties in measurement, some researchers of child maltreatment have observed the relative “neglect of neglect” (see Dubowitz, Reference Dubowitz1994). This is particularly notable given that neglect leaves no visible marks or bruises but has a devastating impact. Key to characterizing a lack of care is the ability to understand what contact is insufficient, thus there is a need to define (and measure) what caregiving is “good enough” (Humphreys, Reference Humphreys2019). Implicit in issues of measurement is understanding the quality of interaction (e.g., high levels of close caregiver–child proximity do not necessarily translate into positive interactions). Indeed, harsh and threatening (and worse) caregiver–child interactions occur in close proximity. Notably, infants (<12 months) are at the highest risk for child maltreatment and fatalities (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau, 2021), perhaps due not only to the high level of dependence on adults for survival, but also the significant demands and physical closeness required for meeting infant needs. Sadly, the types of injuries identified in autopsies following the deaths of maltreated children indicate that their parents are those most often responsible (e.g., shaken baby syndrome/abusive head trauma; [Antonietti et al., Reference Antonietti, Resseguier, Dubus, Scavarda, Girard, Chabrol and Bosdure2019; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau, 2021]).

Early caregiver–child interactions provide a roadmap, of sorts, for children as they navigate the larger world. The quantity and quality of the interactions shape children’s view of themselves with the goal of producing well-rounded individuals who are capable of surviving and reproducing in the outside world. The DMAP model discussed above (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan and Lambert2014) is concerned with how these experiences may impact child development (see Ellis et al., in press in this issue for a more detailed discussion). Drawing from a life history theory, Ellis et al. (Reference Ellis, Figueredo, Brumbach and Schlomer2009) propose a harshness/unpredictability model which describes why variations in caregiving may occur. This model proposes that environmental harshness and environmental unpredictability are two key dimensions of individual experience, influenced by evolutionary adaptations (e.g., “ancestral cues”) and ecological contexts (e.g., neighborhood quality, socioeconomic status), which shape the strategies that individuals employ when making decisions about resource allocation. These dimensions of harshness (externally caused levels of morbidity-mortality) and unpredictability (spatial-temporal variation in harshness) are proposed as important determinants of variations in caregiving behavior and as significantly influential for early development. For example, environmental harshness has been shown to impede or undermine high-quality caregiver–child relationships including proximity; parental effort (e.g., co-sleeping effort, time spent breastfeeding, parental responsiveness) was found to be lower in cultures higher in environmental hazards, such as pathogen stress, famine, and warfare (Quinlan & Quinlan, Reference Quinlan and Quinlan2007). Conceptually, the DMAP model and the harshness/unpredictability model can be integrated to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the how and why of development (Ellis et al., in press), with implications for measuring proximity in caregiver–child relationships as it relates to deprivation (e.g., low cognitive stimulation) and for understanding why variations in proximity within caregiving relationships exist.

Future directions and conclusion

The expansive research on caregiver–child proximity across fields demonstrates the relevance of this topic to the study of early experience. Methodological challenges in assessing caregiver–child proximity limit our ability to measure the full breadth of these experiences to comprehensively characterize the child’s environment. Like with many difficult to operationalize constructs, there is little agreement on how to measure it, the timescales and child ages at which it should be measured, and which parties merit attention (see Tables 1–3 which demonstrate the breadth of proximity measurement across studies). Gaining confidence in the assessment is a necessary step in order to be more clearly able to understand the effects of caregiver–child proximity on children’s adaptive and maladaptive outcomes. From a dimensional framework, where less proximity with a caregiver may be a marker of deprivation, lower levels of proximity between a caregiver and child, particularly early in life, may result in maladaptive outcomes. Nevertheless, evidence of increased autonomy among children whose parents practice distal forms of parenting (Keller et al., Reference Keller, Yovsi, Borke, Kärtner, Jensen and Papaligoura2004) suggest that there may be trade-offs between caregiver support and independence, making it less clear whether a child’s response to lower support is adaptive versus maladaptive (and likely this depends on context; [Frankenhuis et al., Reference Frankenhuis, Young and Ellis2020]). Further, probing these associations may require nuanced characterizations of the environment (e.g., understanding the relative and combined impact of physical distance, physical contact, quality of touch, proximity experiences across nonmaternal caregivers, cultural and individual differences and how each of these change over time and as a function of developmental stage and motor competencies). These questions are key to understanding children’s complex experiences and how these experiences influence child outcomes. There are many avenues for future research, including methodological and theoretical/empirical considerations, that we suggest may be useful to fill important gaps linking variation in early experiences to child functioning.

Methodological considerations for future research

Few studies employ multiple methods to assess proximity or touch, and methods vary greatly, making it difficult to generalize findings (see Brzozowska et al., Reference Brzozowska, Longo, Mareschal, Wiesemann and Gliga2021 for a review of research approaches to measure touch). The development of new methodological tools offers opportunities for research on caregiver–child proximity, enabling more efficient measurement of movement, distance, and touch (see Table 1 for description of measurement methods). Video interactions have long been a gold standard; however, these methods are limited in that they are intrusive and may impact naturalistic behavior. Video is often limited to specific environments (e.g., a laboratory setting or participant’s home), impacting the ability to record caregiver–child proximity and interactions in places that are more likely to evoke attachment systems (e.g., playground or park). New methods that measure interpersonal distance and are not limited to video-capture technology are critical for the progression of this area of research. Devices that facilitate recording of distance between caregivers, such as the MIIKA (see Table 1; Guida et al., Reference Guida, Scano, Storm, Biffi, Reni and Montirosso2021), provide opportunities for researchers to record nuances in caregiver–child proximity in a laboratory setting (recording multiple aspects of proximity including distance, frequency, and speed of approaches or separations). However, tools that precisely measure proximity in a laboratory setting may be difficult to use in more ecologically valid contexts (e.g., within caregiver homes or in childcare settings).

Methodological challenges to assessing proximity motivated our development of the TotTag (part of the SociTrack system; [Biri et al., Reference Biri, Jackson, Thiele, Pannuto and Dutta2020]). The TotTag, a small infrastructure-free, wearable device, uses time-of-flight technology to continuously measure physical distance between wearers within cm accuracy (Salo et al., Reference Salo, Pannuto, Hedgecock, Biri, Russo, Piersiak and Humphreys2021). This tool facilitates our ability to characterize children’s physical environments, specifically proximity relationships between children and multiple caregivers in an ecologically valid setting (e.g. while at home). Further, with such tools, we can characterize the lack of a physically available caregiver; filling an important gap related to early adversity given that assessing the presence of something (e.g., physical abuse) is much clearer than assessing the absence of something (e.g., insufficient contact with a caregiver). This ability to better measure the lack of a physically available caregiver has clear relevance to studies investigating child neglect or differentiating levels of deprivation of children in institutional care.

Defining “caregiver” in caregiver–child proximity research